Antiplatelet Therapy during the First Year after Acute Coronary Syndrome in a Contemporary Italian Community of over 5 Million Subjects

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Analyzed Data

2.3. Cohort Selection and Antiplatelet Regimens

2.4. Patient Clinical Characteristics and Index Revascularizations

2.5. Antiplatelet Treatment Coverage and Switching at One Year

2.6. Other Antithrombotic Agents

2.7. Rehospitalizations and Healthcare Costs

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

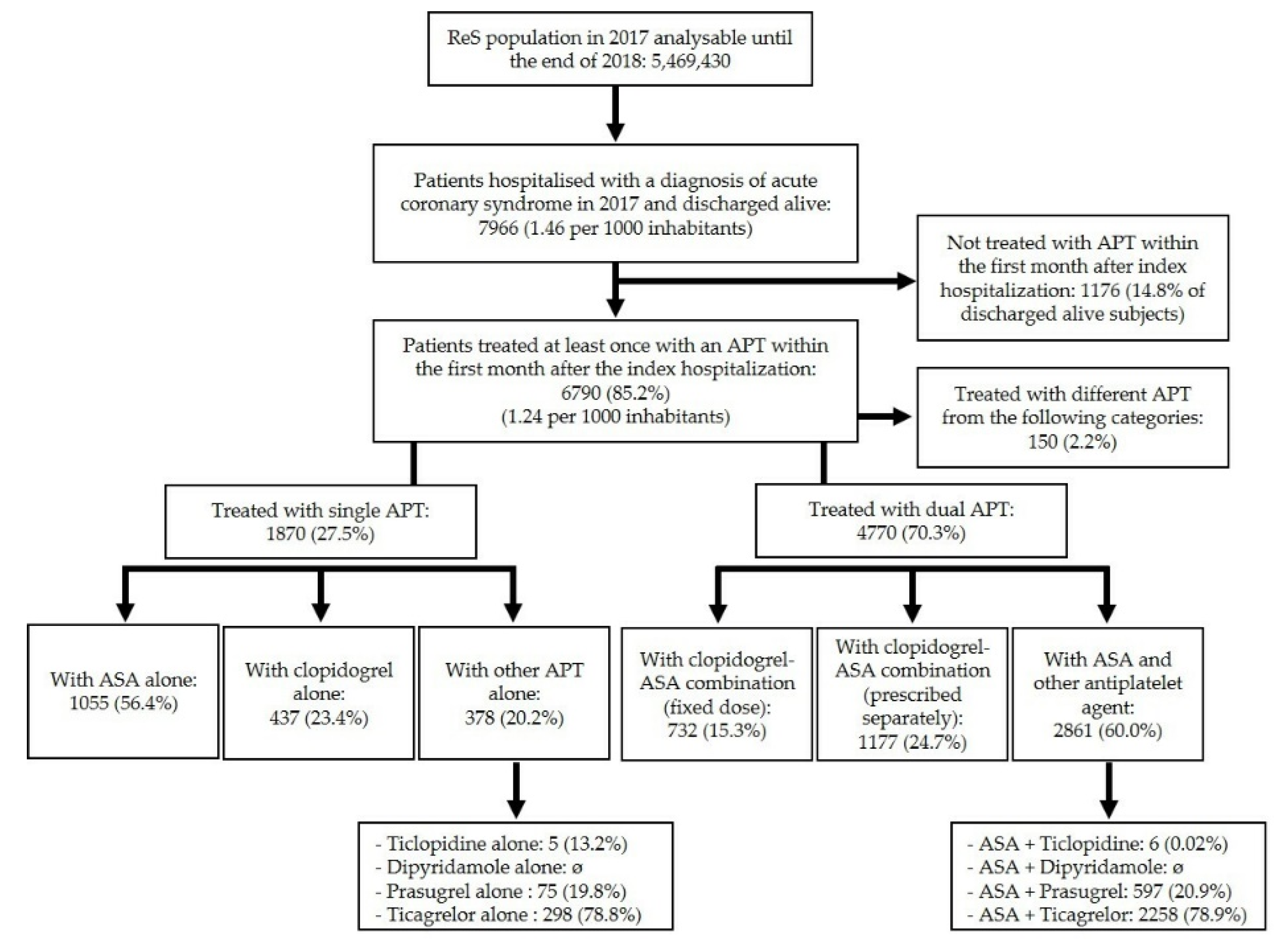

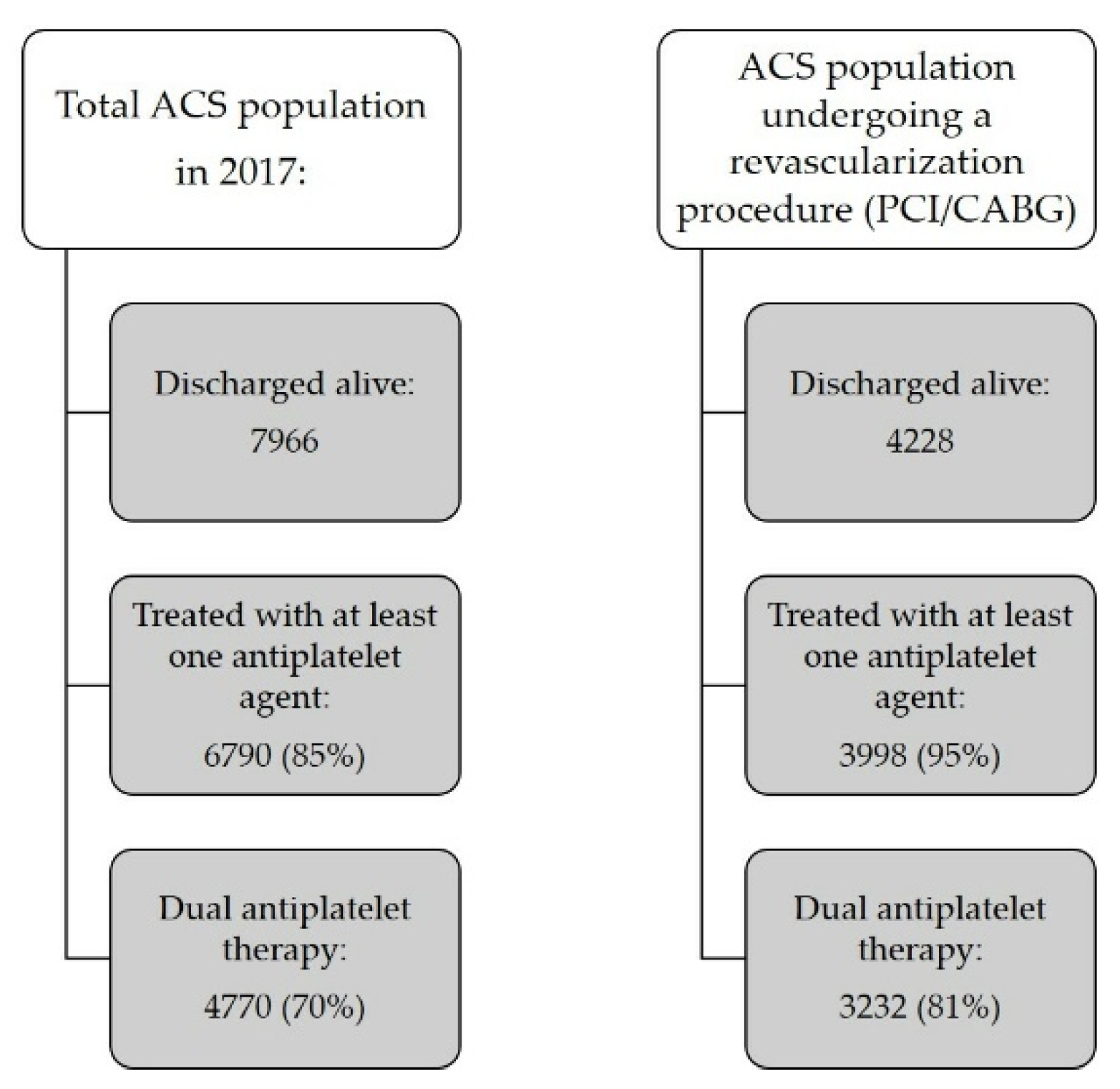

3.1. Cohort Selection and Antiplatelet Regimens

3.2. Clinical Characteristics

3.3. Revascularization Procedures

3.4. Annual Antiplatelet Treatment Coverage and Switching

3.5. Other Antithrombotic Agents

3.6. Rehospitalizations

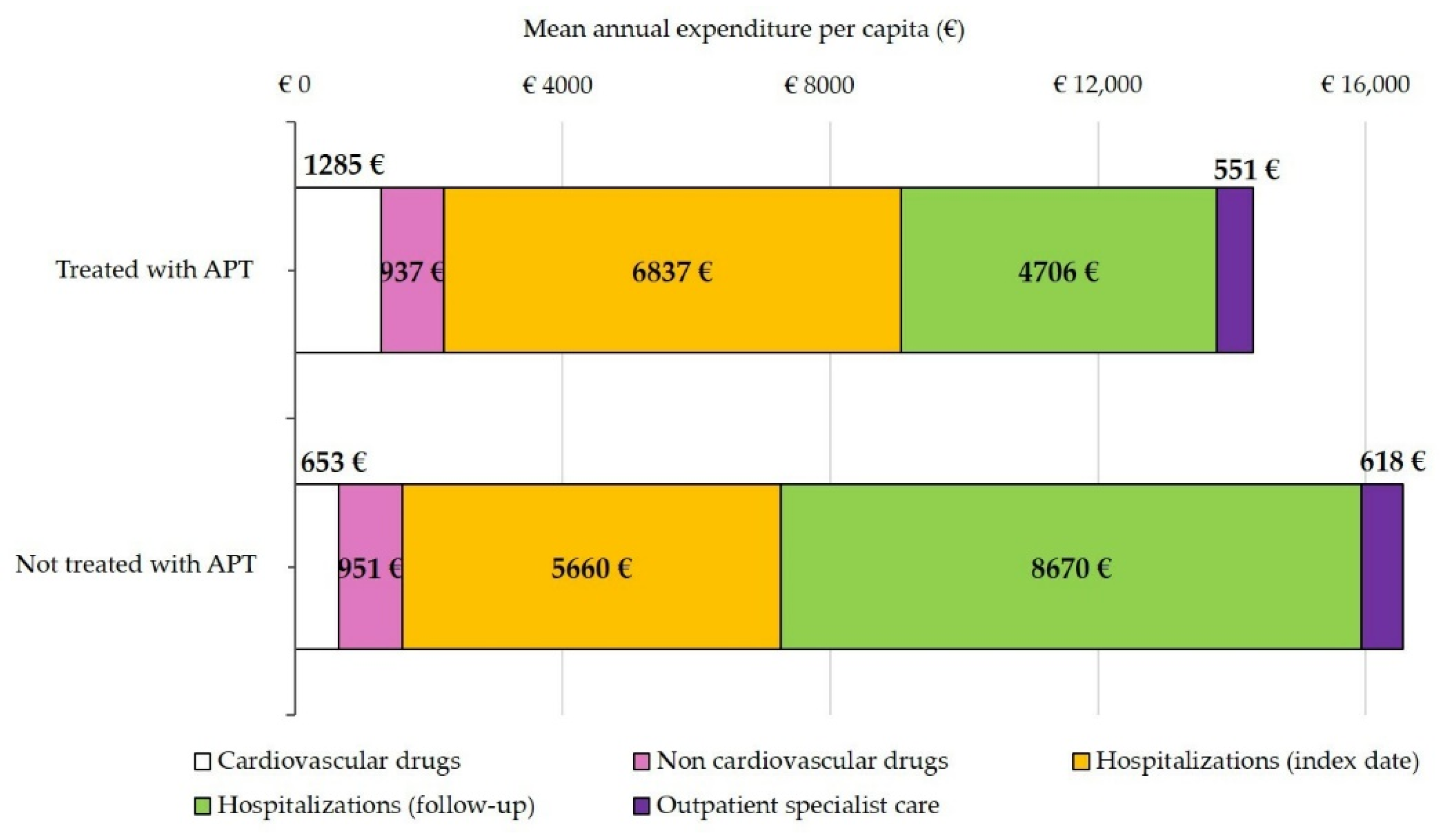

3.7. Healthcare Costs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, R.D.; Chin, B.S.; Lip, G.Y. Antithrombotic therapy in acute coronary syndromes. BMJ 2002, 325, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collet, J.-P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthélémy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1289–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schömig, A.; Neumann, F.-J.; Kastrati, A.; Schühlen, H.; Blasini, R.; Hadamitzky, M.; Walter, H.; Zitzmann-Roth, E.-M.; Richardt, G.; Alt, E.; et al. A Randomized Comparison of Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Therapy after the Placement of Coronary-Artery Stents. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, M.B.; Baim, D.S.; Popma, J.J.; Gordon, P.C.; Cutlip, D.E.; Ho, K.K.L.; Giambartolomei, A.; Diver, D.J.; Lasorda, D.M.; Williams, D.O.; et al. A clinical trial comparing three antithrombotic-drug regimens after coronary-artery stenting. Stent Anticoagulation Restenosis Study Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1665–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of Clopidogrel in Addition to Aspirin in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes without ST-Segment Elevation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Braunwald, E.; McCabe, C.H.; Montalescot, G.; Ruzyllo, W.; Gottlieb, S.; Neumann, F.-J.; Ardissino, D.; De Servi, S.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Prasugrel versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, P.G.; Huber, K.; Andreotti, F.; Arnesen, H.; Atar, D.; Badimon, L.; Bassand, J.-P.; De Caterina, R.; Eikelboom, J.; Gulba, D.; et al. Bleeding in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary interventions: Position paper by the Working Group on Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1854–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sangen, N.M.R.; Rozemeijer, R.; Chan Pin Yin, D.; Valgimigli, M.; Windecker, S.; James, S.K.; Buccheri, S.; Berg, J.M.T.; Henriques, J.P.S.; Voskuil, M.; et al. Patient-tailored antithrombotic therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheugt, F.W.A.; Huber, K.; Clemmensen, P.; Collet, J.P.; Cuisset, T.; Andreotti, F. Platelet P2Y12 Inhibitor Monotherapy after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: An Emerging Option for An-tiplatelet Therapy De-escalation. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Maggioni, A.P.; Dondi, L.; Pedrini, A.; Ronconi, G.; Calabria, S.; Cimminiello, C.; Martini, N. The use of antiplatelet agents after an acute coronary syndrome in a large community Italian setting of more than 12 million subjects. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2019, 8, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CINECA—Interuniversity Consortium. Available online: https://www.cineca.it (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- ISTAT. Geo Demo Istat. Bilancio Demografico e Popolazione Residente al 31 Dicembre 2017 [Demographics and Resident Population the 31st December 2017]. 2018. Available online: https://demo.istat.it (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Piccinni, C.; Cevoli, S.; Ronconi, G.; Dondi, L.; Calabria, S.; Pedrini, A.; Maggioni, A.P.; Esposito, I.; Addesi, A.; Favoni, V.; et al. Insights into real-world treatment of cluster headache through a large Italian database: Prevalence, prescription patterns, and costs. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggioni, A.P.; Dondi, L.; Andreotti, F.; Calabria, S.; Iacoviello, M.; Gorini, M.; Gonzini, L.; Piccinni, C.; Ronconi, G.; Martini, N. Prevalence, clinical impact and costs of hyperkalaemia: Special focus on heart failure. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 51, e13551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronconi, G.; Dondi, L.; Calabria, S.; Piccinni, C.; Pedrini, A.; Esposito, I.; Martini, N. Real-world Prescription Pattern, Discontinuation and Costs of Ibrutinib-Naïve Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: An Italian Healthcare Administrative Database Analysis. Clin. Drug Investig. 2021, 41, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32016R0679 (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- WHO. ATC/DDD Index 2022. Available online: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Ministero del Lavoro, della Salute e delle Politiche Sociali. Classificazione delle Malattie, dei Traumatismi, degli Interventi Chirurgici e delle Procedure Dagnostiche e Terapeutiche. Versione Italiana della ICD9-CM. 2007. Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2251_allegato.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2022).

- Jang, H.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Song, Y.-K.; Shin, J.-Y.; Lee, H.-Y.; Ahn, Y.M.; Oh, J.M.; Kim, I.-W. Antidepressant Use and the Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients Without Known Cardiovascular Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 594474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuwaqqat, Z.; Jokhadar, M.; Norby, F.; Lutsey, P.L.; O’Neal, W.T.; Seyerle, A.; Soliman, E.Z.; Chen, L.; Bremner, J.D.; Vaccarino, V.; et al. Association of Antidepressant Medication Type With the Incidence of Cardiovascular Disease in the ARIC Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.-C.; Gedeborg, R.; Nicholas, O.; James, S.; Jeppsson, A.; Wolfe, C.; Heuschmann, P.; Wallentin, L.; Deanfield, J.; Timmis, A.; et al. Acute myocardial infarction: A comparison of short-term survival in national outcome registries in Sweden and the UK. Lancet 2014, 383, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimminiello, C.; Dondi, L.; Pedrini, A.; Ronconi, G.; Calabria, S.; Piccinni, C.; Friz, H.P.; Martini, N.; Maggioni, A.P. Patterns of treatment with antiplatelet therapy after an acute coronary syndrome: Data from a large database in a community setting. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018, 26, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbel, M.; Qaderdan, K.; Willemsen, L.; Hermanides, R.; Bergmeijer, T.; de Vrey, E.; Heestermans, T.; Gin, M.T.J.; Waalewijn, R.; Hofma, S.; et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): The randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgimigli, M.; Frigoli, E.; Heg, D.; Tijssen, J.; Jüni, P.; Vranckx, P.; Ozaki, Y.; Morice, M.-C.; Chevalier, B.; Onuma, Y.; et al. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after PCI in Patients at High Bleeding Risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1643–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, B.; James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 119–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goldstein, C.M.; Gathright, E.C.; Garcia, S. Relationship between depression and medication adherence in cardiovascular disease: The perfect challenge for the integrated care team. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rolnick, S.J.; Pawloski, P.A.; Hedblom, B.D.; Asche, S.E.; Bruzek, R.J. Patient Characteristics Associated with Medication Adherence. Clin. Med. Res. 2013, 11, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deshpande, C.G.; Kogut, S.; Willey, C. Real-World Health Care Costs Based on Medication Adherence and Risk of Stroke and Bleeding in Patients Treated with Novel Anticoagulant Therapy. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2018, 24, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Medicines Utilisation Monitoring Centre. National Report on Medicines Use in Italy; Italian Medicines Agency: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| ACS Population, n = 7966 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with APT at 1 Month (n = 6790 *) | ASA Alone (n = 1055) | Clopidogrel Alone (n = 437) | Other APT Alone (n = 378) | Clopidogrel + ASA FDC (n = 732) | Clopidogrel + ASA not FDC (n = 1177) | ASA + Other APT (n = 2861) | Patients Untreated with APT (n = 1176) | |

| Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics | ||||||||

| Mean age, years ± SD | 69 ± 13 | 71 ± 12 | 75 ± 12 | 68 ± 11 | 74 ± 11 | 74 ± 12 | 64 ± 12 | 73 ± 12 |

| Males, n (%) | 4682 (69) | 665 (63) | 246 (56) | 300 (79) | 490 (67) | 708 (60) | 2183 (76) | 684 (58) |

| Arterial hypertension | 5225 (77) | 872 (83) | 400 (92) | 323 (85) | 626 (86) | 1002 (85) | 1873 (66) | 972 (83) |

| Dyslipidemia | 3292 (49) | 532 (50) | 276 (63) | 238 (63) | 428 (59) | 601 (51) | 1136 (40) | 567 (48) |

| Diabetes | 2200 (32) | 369 (35) | 178 (41) | 150 (40) | 296 (40) | 415 (35) | 736 (26) | 435 (37) |

| COPD/Asthma | 1050 (16) | 194 (18) | 103 (24) | 47 (12) | 171 (23) | 245 (21) | 256 (9) | 290 (25) |

| Neoplasia | 520 (8) | 108 (10) | 38 (9) | 31 (8) | 73 (10) | 109 (9) | 148 (5) | 131 (11) |

| Depression | 652 (10) | 126 (12) | 71 (16) | 29 (8) | 71 (10) | 128 (11) | 213 (7) | 126 (11) |

| Patients Treated with Guideline-Recommended Antiplatelet Agents at 1 Month after the Index Date, n = 6640 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 6640) * | ASA Alone (n = 1055) | Clopidogrel Alone (n = 437) | Ticlopidine Alone (n = 5) | Prasugrel Alone (n = 75) | Ticagrelor Alone (n = 298) | Clopidogrel + ASA FDC (n = 732) | ASA + Clopidogrel (n = 1177) | ASA + Ticlopidine (n = 6) | ASA + Prasugrel (n = 597) | ASA + Ticagrelor (n = 2258) |

| Patients treated with the same APT during one year of follow-up, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 5161 (78) | 850 (81) | 197 (45) | 5 (100) | 10 (13) | 43 (14) | 477 (65) | 1006 (85) | 4 (67) | 553 (93) | 2016 (89) |

| Patients with appropriate treatment coverage (≥80% of one-year follow-up dosing) among non-switchers, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 3418 (66) | 569 (67) | 93 (47) | 2 (40) | 7 (70) | 29 (67) | 366 (77) | 473 (47) | 0 (0) | 437 (79) | 1442 (72) |

| Patients switching APT during follow-up, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 1479 ^ (22) | From ASA alone (n = 205) | From Clopidogrel alone (n = 240) | From Ticlopidine alone (n = 0) | From Prasugrel alone (n = 65) | From Ticagrelor alone (n = 255) | From Clopidogrel + ASA FDC (n = 255) | From ASA + Clopidogrel (n = 171) | From ASA + Ticlopidine (n = 2) | From ASA + Prasugrel (n = 44) | From ASA + Ticagrelor (n = 242) |

| To ASA | - | 227 (95) | - | 63 (97) | 245 (96) | 111 (44) | - | - | - | - |

| To Clopidogrel | 120 (59) | - | - | 5 (8) | 28 (11) | 182 (71) | - | 1 (50) | 21 (48) | 128 (53) |

| To Ticlopidine | 5 (2) | - | - | - | - | 1 (0) | 6 (4) | - | - | 3 (1) |

| To Prasugrel | 6 (3) | - | - | - | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | - | - | 29 (12) |

| To Ticagrelor | 66 (32) | 3 (1) | - | 1 (2) | - | 11 (4) | 18 (11) | - | 12 (27) | - |

| To ASA + Clopidogrel FDC | 29 (14) | 37 (15) | - | 5 (8) | 14 (6) | - | 149 (87) | 1 (50) | 15 (34) | 99 (41) |

| Cause of Rehospitalization | ACS Patients Treated withany APT at 1 Month (n = 6790) | ACS Patients Untreated with APT at 1 Month (n = 1176) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICD9CM | Primary Diagnosis (Description) | Patients Rehospitalized within 1 Year, n (%) | |

| 414 | Coronary atherosclerosis, aneurysm, and dissection, other/unspecified form of chronic ischemic heart disease | 1488 (21) | 94 (8) |

| 410 | Acute myocardial infarction | 914 (14) | 131 (11) |

| 411 | Other acute/subacute form of ischemic heart disease | 337 (5) | 66 (6) |

| 428 | Heart failure | 240 (4) | 70 (6) |

| 413 | Chronic coronary syndrome | 232 (3) | 40 (3) |

| 429 | Undefined complication of heart disease | 224 (3) | 150 (13) |

| V43 | Organ or tissue transplant | 89 (1) | 38 (3) |

| 518 | Lung disease | 82 (1) | 54 (7 5) |

| 584 | Acute renal failure | 60 (1) | - |

| 786 | Other respiratory or chest symptoms | 53 (1) | 41 (3) |

| 424 | Endocarditis | - | 25 (2) |

| * Total number of rehospitalized patients at 1 year | 3637 (54) | 772 (66) | |

| Healthcare Category | ACS Population n = 7966 | |

|---|---|---|

| Treated with APT at One Month (n = 6790) | Untreated with APT at One Month (n = 1176) | |

| Mean Expense per Capita in € (% of Overall Expenditure; % of Specific Category) | ||

| Drugs | 2222 (16) | 1604 (10) |

| Cardiovascular | 1285 (58) | 653 (41) |

| Non-cardiovascular | 937 (42) | 951 (59) |

| Hospitalizations | 11,543 (81) | 14,330 (87) |

| Index date | 6837 (59) | 5660 (40) |

| During follow-up | 4706 (41) | 8670 (61) |

| Outpatient specialist care | 551 (4) | 618 (4) |

| Annual total | 14,316 (100) | 16,552 (100) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Calabria, S.; Andreotti, F.; Ronconi, G.; Dondi, L.; Campeggi, A.; Piccinni, C.; Pedrini, A.; Esposito, I.; Addesi, A.; Martini, N.; et al. Antiplatelet Therapy during the First Year after Acute Coronary Syndrome in a Contemporary Italian Community of over 5 Million Subjects. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164888

Calabria S, Andreotti F, Ronconi G, Dondi L, Campeggi A, Piccinni C, Pedrini A, Esposito I, Addesi A, Martini N, et al. Antiplatelet Therapy during the First Year after Acute Coronary Syndrome in a Contemporary Italian Community of over 5 Million Subjects. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(16):4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164888

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalabria, Silvia, Felicita Andreotti, Giulia Ronconi, Letizia Dondi, Alice Campeggi, Carlo Piccinni, Antonella Pedrini, Immacolata Esposito, Alice Addesi, Nello Martini, and et al. 2022. "Antiplatelet Therapy during the First Year after Acute Coronary Syndrome in a Contemporary Italian Community of over 5 Million Subjects" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 16: 4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164888

APA StyleCalabria, S., Andreotti, F., Ronconi, G., Dondi, L., Campeggi, A., Piccinni, C., Pedrini, A., Esposito, I., Addesi, A., Martini, N., & Maggioni, A. P. (2022). Antiplatelet Therapy during the First Year after Acute Coronary Syndrome in a Contemporary Italian Community of over 5 Million Subjects. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(16), 4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164888