Abstract

Background: Natural disasters happen in an increased frequency, and telemental health interventions could offer easily accessible help to reduce mental health symptoms experienced by survivors. However, there are very few programs offered to natural disaster survivors, and no research exists on therapists’ experiences with providing blended interventions for natural disaster survivors. Aims: Our qualitative case study aims to describe psychologists’ experiences with an online, therapist-assisted blended intervention for survivors of the Fort McMurray wildfires in Alberta, Canada. Method: The RESILIENT intervention was developed in the frames of a randomized controlled trial to promote resilience after the Fort McMurray wildfires by providing survivors free access to a 12-module, therapist-assisted intervention, aiming to improve post-traumatic stress, insomnia, and depression symptoms. A focus group design was used to collect data from the therapists, and emerging common themes were identified by thematic analysis. Results: Therapists felt they could build strong alliances and communicate emotions and empathy effectively, although the lack of nonverbal cues posed some challenges. The intervention, according to participating therapists, was less suitable for participants in high-stress situations and in case of discrepancy between client expectations and the intervention content. Moreover, the therapists perceived specific interventions as easy-to-use or as more challenging based on their complexity and on the therapist support needed for executing them. Client engagement in the program emerged as an underlying theme that had fundamental impact on alliance, communication, and ultimately, treatment efficiency. Therapist training and supervision was perceived as crucial for the success of the program delivery. Conclusions: Our findings provided several implications for the optimalization of blended interventions for natural disaster survivors from our therapists’ perspective.

1. Introduction

Due to climate change, natural disasters and other extreme events have become more frequent and intense recently [1], and their devastating impact includes various mental health consequences for the survivors [2]. Previous studies estimated that up to forty percent of natural disaster survivors develop some type of mental health symptoms, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and insomnia [3]. Psychotherapy has been found to be effective in the treatment of such problems in the context of natural disasters. For instance, after hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, cognitive-behavior therapy significantly reduced survivors’ symptom levels [4,5]. Even though it is essential to be able to provide psychological support after natural disasters, having access to sufficient mental health services at the location of the disaster is often a serious challenge.

Telemental health interventions have many advantages compared to in-person settings, including providing help for those who would not otherwise have access to mental health providers via in-person settings [6,7]. Among telemental health interventions, blended interventions are web-based interventions guided by a therapist that combine the advantages of asynchronous online programs and face-to-face, synchronous, personalized sessions with a therapist [8,9], which may be conducted either over the Internet or in person. Blended interventions have been suggested to have the most benefit by boosting treatment adherence, intensifying the learning process, personalizing and adjusting the intervention content to the client’s needs [9], as well as reducing associated therapist time and cost by providing a large proportion of the therapy content on the web to be utilized by the client [8]. Blended interventions appear to have the potential to make telemental health interventions suitable for more clients at lower therapist time and associated costs and may be a candidate for delivering telemental health interventions rapidly after natural disasters. Despite the many advantages of blended interventions over exclusively online, self-help modules, as well as over exclusively face-to-face sessions with a therapist, there are very few existing blended intervention programs providing help for natural disaster survivors.

Telemental health interventions have been underutilized mostly due to negative attitudes and concerns towards some of its aspects (see [10]) before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the advantages of telemental health interventions have become especially salient during the past months, when the COVID-19 pandemic and the related physical distancing restrictions forced therapists and clients to switch to remote therapy en masse [11]. Research suggests that therapists generally hold neutral or positive views of telemental health interventions [12,13,14,15]; however, providers are often reluctant to provide telemental health due to concerns and more negative views on it [16,17,18,19]. One common concern regards the ability to build therapeutic alliance [10,20,21,22]. Despite the fact that the quality of working alliance has been found to be excellent in videoconference (see review by [23]) and comparable to in-person therapies (e.g., [24,25]), providers are often worried that they would not be able to build strong rapport and develop alliance remotely [26]. Concerns and negative experiences, on the other hand, have been found to reduce the likelihood of intention to use telemental health in the future [26].

Another major concern regarding the providing of telemental health interventions is whether therapist and client can communicate emotions and empathy effectively remotely [6,27]. Despite research evidence that online channels do not influence emphatic accuracy [28], a common concern is that the online medium prevents the communication of empathy, warmth, and understanding [10]. Consequently, therapists are usually more favorably disposed toward videoconferencing as opposed to telephone or text therapy, as this modality enables them to observe physical cues and thus preserves an important element of in-person therapy [29].

Finally, therapists are also often concerned about the suitability of telemental health interventions to a certain type of clientele and situations [29,30]. Safety and legal concerns are common regarding interventions without physical proximity to the patient, and complex and severe client presentations, such as personality disorder, emotional instability, impulsivity, past suicide attempts, or any crisis situation are often perceived by clinicians as not suitable for telemental health settings [29].

However, we know that the therapists’ concerns and perceptions of telemental health vary. Recent studies showed that more previous experience with providing telemental health interventions and a larger teletherapy caseload were associated with more positive views on using telemental health [12,31,32]. Moreover, older therapists, and therapists with more clinical experience also reported more positive experiences with telemental health compared to their younger and less experienced counterparts [16,33].

Fort McMurray Wildfires

On 1 May 2016 in Fort McMurray (Alberta), a major wildfire destroyed approximately 2400 homes and buildings and led to the massive displacement of 88,000 people, making it the most expensive natural disaster in Canadian history at the time. Many individuals faced direct or potential threats to their life or health, were separated from loved ones, and incurred significant losses. Families had to be displaced for several weeks and up to several months. For a report of the evacuees’ experiences three months and three years after the fires, see [34].

A year after the disaster, in a representative sample of 1510 evacuees, 38% reported symptom levels indicative of a probable diagnosis of either post-traumatic stress, major depression, insomnia, generalized anxiety, substance use disorder, or a combination of these disorders [35]. In order to provide support to the evacuees with these symptoms, our team of researchers and clinicians gathered an arsenal of well-evidenced CBT strategies into a 12-module online RESILIENT therapy program.

The RESILIENT platform Is a therapist-guided, online self-help treatment; its content was developed following a preliminary study of Fort McMurray residents who were evacuated during the fires, which showed that they had significant symptoms of PTSD, insomnia, and depression after the event [35].

The platform was hosted by Laval University, and the graduate psychology students were included as therapists in the program. A randomized control trial of 136 individuals who participated in the intervention showed that the RESILIENT program was successful and showed large effect sizes of symptom improvement in participants who completed at least half of the treatment. For further details on the RCT, see [36].

The present study aims to learn about the RESILIENT intervention from a different angle, by exploring trainee therapists’ first experiences with providing blended therapy for survivors of the Fort McMurray fires, in the context of the RESILIENT program. More specifically, our aims were twofold: (1) To explore therapists’ experiences with areas of common concerns described in the literature regarding telemental health services, such as the ability to build alliance online, communicate emotions and empathy, and suitability of remote interventions for all clients; (2) To explore therapists’ experiences with delivering the RESILIENT intervention, that is, their views on the intervention content and platform, as well as the training and supervision process.

We used a focus group design to learn about the therapists’ experiences. We selected a focus group design because, in contrast with individual interviews, focus groups allow for a discussion between group members, which typically widens the range of responses, brings up forgotten details, or triggers new ideas. In addition, due to the shared experience, the group dynamic often creates a sense of confirmation and of less inhibition in participants to freely share their views [37].

2. Method

2.1. The Resilient Intervention

The intervention was developed for a randomized controlled trial assessing the effectiveness of a blended intervention including online modules and synchronous therapist sessions either by phone or video conference for the evacuees of the Fort McMurray (Alberta, Canada) wildfires. Evacuees completed online symptom assessments, including PTSD (PTSD Symptoms Checklist, PCL-5; [38]), depression (Patient Health Questionnaire—Depression Subscale, PHQ-9, [39]), and insomnia measures (Insomnia Severity Index, ISI; [40]). Participants meeting inclusion criteria were offered free treatment. Inclusion criteria were: (1) significant post-traumatic stress symptoms (PCL ≥ 23) or (2) some post-traumatic stress symptoms (PCL ≥ 10) and at least mild depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 5) and/or at least subclinical insomnia symptoms (ISI ≥ 8).

The intervention consisted of a therapist-assisted online cognitive-behavior therapy focusing on post-traumatic stress, sleep, and mood. It comprised 12 sessions with modules of psychoeducation about PTSD, sleep and depression, prolonged exposure to avoided situations and memories, sleep management strategies (restriction of time in bed, sleep hygiene education, nightmare image rehearsal), behavioral activation, breathing and mindfulness exercises, cognitive restructuring, and relapse prevention. Participants had to work on each week’s session online individually by reading educational material, reflecting on their own experiences by answering questions, planning their homework exercises, and filling out online journals about sleeping, breathing exercises, exposure, and behavior activation. They met a therapist via either videoconference (Skype) or phone, according to the participants’ preference, after completing each session to discuss the given topic and review their online work as well as the homework (exercises in-between sessions). Meetings with the therapists were 30 min long, and usually weekly sessions, depending on the participant’s online progress. Preliminary results have been previously published in French [41].

2.2. Participating Therapists

Seven clinical psychology graduate students, that is, all the therapists in the program, participated as therapists in the program. All therapists were female with a mean age of 25.86 (range: 22–30, SD = 3.08). None of the therapists had previous experience with remote therapy. Therapists had about 2 years of in-person clinical experience (mean = 2.13 years; range: 0–4.5, SD = 1.67), and only one therapist was beginner. Altogether, 69 clients were invited to participate in the program and were assigned to a therapist; each therapist had 9.75 clients assigned to them on average (range: 3–17, SD = 3.99).

2.3. Procedure and Data Analysis

Two focus groups were conducted to collect data from each participating therapist shortly after the termination of the intervention. Each focus group lasted for 120 min. All 7 therapists provided data about their experiences by participating in the two focus groups (n = 3 and n = 6, two therapists participated in both). The focus groups used a semi-structured interview guide with open questions. Questions focused on general impressions regarding the intervention, perceived challenges for the therapists and the clients, and more specific questions regarding experiences with phone and video conferencing with the clients (such as developing alliance and feeling empathy), the online platform, the content of the intervention, and finally, suggestions for improving the intervention. The focus group interviews were audio recorded and later transcribed. Given the bilingual milieu, where all participants used both English and French in professional and daily communication, the therapists responded in either of these languages within the same group, according to their preferences, or switched from one to the other language as they would naturally do outside of the focus group setting. The possibility to use either English or French allowed participants to express themselves in the language they felt more comfortable with, while not risking hindering the process of understanding. The transcription kept the original languages, and quotes in French were translated to English for the present study.

Two graduate clinical psychology students (who did not participate in the study) conducted thematic analysis on the transcribed data on the guidelines provided by Braun and Clarke (2006). The qualitative analysis included the following phases: (1) generating initial codes, (2) identifying emerging common themes, (3) reviewing the themes, arranging the themes under a priori established categories (building alliance, communicating emotions and feeling empathy, suitability of intervention) as well as defining emerging categories (platform, intervention content, training, and supervision), and (4) finally, refining the definition, specifics of each theme, as well as the thematic map). Illustrative quotes were selected and translated from French to English. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Laval University Institutional Review Board, and participants provided informed consent.

3. Results

The themes were categorized under general concerns regarding alliance, communicating emotions and empathy, and suitability (Table 1), and specific issues, including intervention content, platform, and training and supervision (Table 2).

Table 1.

Therapist Experiences with Alliance, Communicating Emotions and Empathy, and Suitability.

Table 2.

Therapist Experiences with the Content, Platform, and with Training and Supervision.

3.1. Alliance and Client Engagement

Despite previous apprehensions, all therapists had generally positive experiences with establishing and maintaining alliance with clients via phone calls and video conferencing (7/7); as one of them described “It was more rich than I thought, since there was a screen between us, it was interesting to see that I was able to bond with the [clients] even though they were far away, so yes, that surprised me.” (P1). Most therapists felt that video sessions were more helpful for feeling closer to clients (5/7), and they had positive experiences with phone sessions in general, although some signalled that it took more time to build rapport over the phone (1/7).

Client engagement emerged as a central theme affecting alliance: the therapists felt that they worked well with motivated clients, whereas client non-compliance negatively affected the alliance (7/7). In reaction to issues with engagement, therapists realized that providing regular encouragement, motivation, and checking in were needed to ensure that clients adhered to the intervention (3/7). Moreover, according to the program protocol, in order to maintain client engagement, therapists had to regularly reach out to clients when they had not heard from them. This was frustrating for most therapists and felt like needing to constantly reach out to clients (4/7), which sometimes even felt like they were harassing the clients (2/7). The therapists’ impression was that the frequent reaching out process appeared to be frustrating for both them and the clients, and most of the time it did not reach its goal of increasing engagement but most probably negatively affected their alliance.

3.2. Communicating Emotions and Empathy

Overall, therapists felt they could adequately sense and communicate emotions and empathy both via video conferencing and phone (7/7). They felt that even when only using audio (phone) and not video, they were able to recognize clients’ emotions, understand their perspectives, and empathize with their traumatic experiences (4/7). One therapist reported that phone sessions, compared to face-to-face, made her less stressed and self-conscious, and consequently more focused with the clients, allowing her to develop better empathy.

Despite being comparable in many aspects, video call sessions were viewed as more favorable than phone sessions in general for various reasons. First, the therapists had better experiences with video sessions with regards to communicating empathy, as they felt a “better presence” with clients (3/7). Second, they also felt that it was harder to assess the clients’ mental state via phone due to a lack of information about their facial expression (4/7). Third, lacking access to non-verbal cues also limited the therapists’ ability to keep the sessions focused on the given topics and not to divert into others (3/7). Some therapists voiced concerns that there might be more distractions around clients during phone session that are hard for the therapist to detect (1/7), and thus sometimes they wondered what the clients were doing during the sessions (2/7).

Despite the overall preference for video calls over phone calls, therapists also experienced its limitations. For example, access to the clients’ nonverbal cues were limited to facial expressions and diminished the therapist’s ability to transmit nonverbal signs (7/7). Moreover, even though therapists could read and communicate emotions via video call in general, the angle, distance, and resolution of the camera set limits to what the therapists could observe, limiting their access to some nonverbal or social cues (5/7).

3.3. Suitability and Client Engagement

According to the therapists, the single most important factor in the success of the intervention was whether the client was motivated and engaged. In turn, client engagement greatly differed based on certain client and situation characteristics (7/7). Therapists felt that client engagement was often polarized: clients were either motivated and active from the beginning until the end, or were less engaged, non-responsive to emails, missing sessions, and the therapists’ efforts to motivate them had a very limited impact on changing this: “Either they were engaged and following every week or it was difficult to engage them and they would do one to three sessions and then it was very difficult, and it took two or three weeks to do another one and they would always postpone it. So, I think it was the main thing with my participants.” (P6) According to the therapists, clients were less engaged if they did not feel that their symptoms were targeted (4/7), for example, for clients who did not have avoidance symptoms, a central focus of the intervention appeared unrelatable.

Therapists also proposed that the presence of severe symptoms or other ongoing life stressors might have contributed to clients’ non-adherence and dropout (2/7): “I only had one participant that dropped out, and for her I think that her symptoms were really severe and for her to do it by herself on the computer, it was just too much, she told me that the first or second sessions she started having nightmares, felt a lot of anxiety. She had flashbacks again, so I think that’s why, she told me that, and she wasn’t sure if she wanted to continue or not. And after that she emailed me back and she never answered, so she dropped out after that.” (P5)

Furthermore, mismatch between client expectation and the offered intervention negatively affected client engagement. Most of the time, the client did not expect that the intervention would take so much time, effort, and emotional investment (7/7), “They didn’t know what they were getting into. Even though we told them in the beginning that it was a self-based intervention, I don’t think that they knew exactly what it was (…) I don’t think that they expected so much work.” (P2)

3.4. Intervention Content

The therapists found the intervention was well-made, the content was clear, well-organized, easy to understand, and that the modules were organized in the right order (7/7); however, the utilization of the exercises mostly depended on client engagement (7/7). According to therapists, engaged clients claimed that this intervention made a difference in their lives (2/7) and especially appreciated the therapist sessions in addition to the online modules (2/7). The utilization of the exercises also depended on the specific needs and symptoms of the clients, and therapists made efforts to repeat helpful exercises and skip less relevant ones in order to adapt to the client’s needs (4/7). “It was really different from one person to another. I feel like all of my participants had their one or two that they really liked and kept during all the program and I don’t believe that any of the intervention wasn’t useful, I think it just depends on the fit with the person. Because they are all in themselves relevant, it just depends on the match.” (P1) The clients sometimes focused on a sole exercise, which still led to significant improvements: “The very use for she was the pleasant activities [behavior activation] and so this is something she really did regularly. So yes, it was helpful and she had issues if I may say, but at the end she had no issues with sleep, and all the things so at the very end she only had to complete the pleasant activities and that was it.” (P1)

The therapists felt that exposure was difficult to do alone (2/7) and in-person assistance would have been helpful for clients (1/7). The insomnia element of the intervention was very helpful for those who had symptoms (5/7), although the online sleep diary was difficult to use (6/7). Behavior activation exercises were popular and helpful in general (4/7). The cognitive restructuring exercise, although the therapists thought it was important, was hard to work with in the blended therapy’s frames, as clients would have needed more support to recognize their own maladaptive thoughts and finding alternatives (4/7). The most utilized exercises were the insomnia, behavior activation, and diaphragmatic breathing interventions (4/7); less utilized exercises included nightmare imagery rehearsal, given that very few clients had nightmares (7/7). Utilization of the online tools, for example sleep diary, and anxiety monitoring before and after interventions, greatly varied, and the majority of clients stopped using them after a few times (6/7). For more detailed description of experiences with the specific exercises see Table 2.

3.4.1. Intervention Platform

Therapists agreed that the platform was clear and easy-to-use, visually pleasing, and inviting (7/7), and most therapist did not experience technical problems. However, clients sometimes forgot to enter their exercise data (2/2) and a technical glitch that resulted in losing client data was very frustrating for clients (1/7).

3.4.2. Training and Supervision

Therapists felt they needed to work on getting prepared for providing the intervention by reading and becoming familiar with the content, exercises, online tools, and learnt a lot about therapy principles and practice (5/7) while receiving a meaningful training experience (1/7). The therapists all felt that the supervision was helpful in providing ideas and a new perspective (4/7), as well as support and frames for approaching complicated situations (2/7) and setting boundaries (1/7).

3.5. Underlying Processes: The Role of Client Engagement

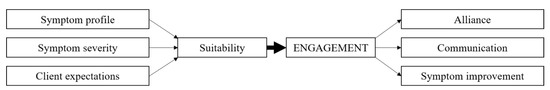

In summary of the results, the following underlying process emerged. Client engagement appears to have a fundamental role in the success of the treatment, with regards to developing strong alliance, provide effective communication, and lead to significant symptom improvement. Client engagement, on the other hand, largely depends on the suitability of the intervention for the client. For clients with severe symptoms or symptom profiles that do not match the intervention’s focus, or for clients with differing expectations, the intervention proved to be less suitable, leading to a lack of client engagement, which negatively impacted the working alliance and communication between client and therapist and, ultimately, symptom improvement (Figure 1). Moreover, besides suitability to client expectations and symptoms, the utilization and helpfulness of specific exercises greatly varied depending on their suitability to the blended intervention format that heavily relied on asynchronous communication. Some exercises worked well without synchronous therapist support; for example, behavior activation or diaphragmatic breathing, whereas others were challenging to execute without in-person or more synchronous remote support (such as exposure exercise, cognitive restructuring).

Figure 1.

Thematic map of therapists’ experiences with alliance, communicating emotions and empathy, and suitability. Note. Client engagement was crucial for the success of the treatment, as it tended to lead to stronger alliance, effective communication, and significant symptom improvement. Client engagement, on the other hand, largely depended on the suitability of the intervention for the client. The intervention was less suitable for clients with symptom profiles that did not match the intervention’s focus, for clients with severe symptoms, and for clients whose expectations did not match the intervention. Problems with suitability lead to a lack of client engagement, which negatively impacted the working alliance and communication between client-therapist and, ultimately, symptom improvement.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to explore therapists’ experiences with providing telemental health in the context of a blended intervention for survivors of a natural disaster. We found that therapists had an overall positive experience with the ability to build alliance, communicate emotions, and empathize with clients via both phone and video sessions, while they identified special advantages and challenges within each domain. Client engagement emerged as a central underlying theme that was perceived as having a fundamental impact on both the process and the outcome of the intervention. This result is in line with a subsequent quantitative analysis of usage data of by the same participants, where Label and colleagues [42] recently found in the same sample of clients that treatment efficacy (reduction in post-traumatic stress, depression, and insomnia symptoms) was related to the number of modules accessed by the client, which, in turn, was predicted by previous engagement (e.g., number of words entered) in preceding modules.

In our study, client engagement was perceived as depending on (1) the match between the client’s symptom profile and the intervention content, (2) symptom severity (overwhelming, severe symptoms often led to disengagement and eventual dropout), and (3) the match between client expectations regarding the program and the actual intervention. Moreover, in our trainee therapists’ view, utilization of specific exercises greatly varied based on the difficulty to execute them without direct and synchronous therapist support within the blended intervention paradigm.

4.1. Alliance

Similar to previous findings (e.g., [26]), trainee therapists in the present study had concerns about the ability to build alliance prior to starting the intervention and were pleasantly surprised by the ease of creating bonds remotely. This finding supports the notion that once therapists are effectively engaged in delivering online intervention, their experiences are usually positive with alliance building [10,11]. While creating bonds proved to be easier than expected, trainee therapists still faced various challenges regarding specific aspects of working with clients. They felt that the ability to build alliance greatly depended on the clients’ engagement to the program (as seen in previous studies as well, e.g., [43]), and maintaining clients’ motivation posed a fundamental challenge to therapists. Based on previous recommendations (e.g., [44]) the study protocol required therapists to reach out to inactive clients regularly in order to maintain engagement; however, this method appeared to be counterproductive, resulted in therapists feeling like they were “chasing the clients”, and posed a strain on the alliance on both sides. Eventually, our therapists found different ways to keep clients engaged, tailor-made for each client, which they perceived as more effective.

Moreover, in contrast with earlier findings where the aspect of alliance regarding agreeing on the goals and tasks was found to be higher in online therapies [45], for our trainee therapists this posed a challenge. Since the modules, exercises, and their order had already been pre-established, the therapists had little space to adjust them to the needs of the actual clients, which frequently resulted in a mismatch between client expectations and the delivered intervention. Moreover, since clients were recruited by the RESILIENT program by offering a free intervention for those with above-threshold symptoms, many clients may not have had a strong motivation to begin with, and when faced with the time and emotional investment required by the program, became even less motivated.

Problems with high degrees of non-adherence are common in online interventions [46], and blended interventions’ synchronous therapist support component are aimed to address this; however, our results suggest that, in itself, this might not be enough. The clients’ specific needs could be better met by making the intervention content and sequence more flexible; this would increase client and therapist agreement on tasks and goals, and consequently, have a positive impact on client engagement. For example, implementing a preliminary phase at the beginning of the intervention where the client’s symptoms are assessed, and matching interventions be selected and arranged in the desired order may be helpful. This phase could be either conducted by a therapist or by an online algorithm, or by a combination of both where the therapist is able to adjust the algorithm’s recommendations based on a collaborative discussion with the client.

4.2. Communicating Emotions and Empathy

Similar to experiences with alliance, trainee therapists were pleasantly surprised by the ease of communicating and feeling empathy both over the phone and in video calls. Video sessions were perceived as preferable to phone due to the availability of visual information and thus the ability to sense the clients’ emotional states and understand their mind states. At the same time, even video calls filtered out the perception of certain nonverbal clues, a common issue that has been raised in previous studies. To address this, Grondin et al. [47] suggested that techniques like exaggeration of nonverbal behaviors and verbal clarification of the client’s affective state can facilitate the empathic phenomenon. Moreover, simple technical adjustment in the video camera placement and settings can also increase connection and the perception of nonverbal cues. For example, setting the camera angle in a way that enables eye contact, and selecting the appropriate camera frame (zooming in and out to show the usual head-to-chest versus larger, head-to-waist frame) allows the perception of nonverbal cues while also maintains a sense of psychological connection [48]. Future studies need to explore the utility of these techniques in telemental health.

4.3. Suitability

Previous studies suggested that online interventions might be less suitable for certain clients, for example, those with severe or complex psychopathology and in crisis situations [29]. In our study, although some of the trainee therapists mentioned symptom severity contributing to unsuitability and non-adherence, the relevance of the intervention content to the client appeared to play a more important role in the client–intervention match. As for alliance, our results regarding suitability indicate the need for developing more personalized treatments in telemental health, and specifically, in blended interventions, instead of utilizing a one-size-fits-all approach [49]. Bettering the fit between client needs and expectations and provided content could improve client engagement and adherence, which has been a major challenge in our current as well as in previous studies.

4.4. Helpful Exercises

Therapists perceived certain interventions as better fits, while others as less good fits for blended interventions. Interventions that need strong emotion regulation skills (e.g., in vivo exposure exercises) or ability to critically engage with one’s thoughts and beliefs (cognitive restructuring) may be challenging for many clients in a remote setting that heavily relies on independent client work. Providing more synchronous therapist contact, i.e., more frequent sessions, or simplifying these exercises from the given client’s treatment protocol could address this problem. Other exercises that need little therapist support but are highly successful (e.g., behavior activation) could also be included in exclusively web-based intervention protocols.

4.5. Professional Support

Training and supervisor support before the preparation and throughout the intervention was perceived as crucial for the trainee therapists, who were young graduate students with relatively little clinical and no telemental health experience. They reported that training and first-hand experience with telemental health positively impacted their attitudes in our study, similarly to earlier findings [11,50]. Since experience with telemental health is also associated with more therapist confidence regarding the ability to build alliance, read emotions, and be emphatic with clients online [26], in order to promote the utilization of telemental health among providers, providing training and ongoing professional support for trainee and novice therapists would be crucial.

4.6. Limitations

As all studies, ours had its limitations as well. First, we had a relatively small sample of participant therapists; however, this is not unusual in qualitative studies. Qualitative inquiry typically uses smaller sample sizes (sometimes even a single participant, [51]) in order to explore a limited number of participants’ subjective experiences in depth, in contrast with quantitative studies, where a larger random sample may better represent the views of a general population [52]. Based on this notion, we included a small number of therapists with the specific experience of participating in the RESILIENCE program, instead of a larger sample of therapists with potential experience in other programs. In addition, for a case study like ours, a focus group design with a relatively small number of participants is recommended, where the participants who are all familiar with the case (i.e., the RESILIENT intervention] are able to share experiences and generate ideas together [53]. Therefore, the fact that we could include all the participating therapists in our focus groups could be in fact considered as a strength of the study.

Second, the trainee therapists’ experiences with providing telemental health within the context of the RESILIENT intervention in rural Canada might not be transferable to other circumstances. Our trainee therapists were all junior with little or no previous therapy experience, and despite the common view that younger people feel more comfortable using technology, earlier research found that more junior therapists with less clinical experience tend to have less positive experiences with providing telemental health compared to their older and more experienced counterparts [16,33]. Therefore, our therapists’ perceptions of the intervention may differ from what older and more experienced therapists would experience under the same circumstances. Moreover, our participants, the specific event of the Fort McMurray fires, and the circumstances in our study were also unique, which may further limit the transferability of the findings.

Furthermore, our therapists within the study had some differences, such as their previous clinical experience and present caseload, which might have also impacted their experiences [35]. However, this case study’s findings regarding therapist concerns and initial first-hand experiences with blended interventions for natural disaster survivors may still be helpful when preparing for new interventions under different circumstances.

5. Conclusions

The therapists in our case study perceived the blended intervention as a significant mental health tool for survivors of a natural catastrophe. The perceived success of this model encourages the implementation of similar blended interventions for survivors of other natural catastrophes in remote areas, or where psychological help is not readily available, as well as for survivors of other type of traumas who are reluctant to seek help in person, for example, sexual assault victims. However, based on our therapists’ experiences, in order to improve the efficiency of such interventions, personalization of the treatment content and sequence, as well as proportion of therapist sessions and web-based content based on client needs, is recommended. Furthermore, providing theoretical and skills-based training in telemental health is recommended to improve the quality of online interventions in crucial areas, such as providing relevant content, building alliance, and specifics of online communication with clients. Our hope is that the accumulating knowledge of the specificities of online interventions for natural disaster survivors will not only inform the development of blended interventions for natural disaster survivors in the future but may also be incorporated in the training of future providers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B., J.L. and G.B.; methodology, V.B., J.L. and G.B.; data analysis, Z.C. and V.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B.; writing—review and editing, V.B., Z.C., J.L., G.B. and S.B.; funding acquisition, G.B., M.-C.O., C.M.M., N.B., T.S.C., S.B., S.G. (Sunita Ghosh), S.G. (Stéphane Guay) and F.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Operating Grant: Health Effects of the Alberta Wildfires program, supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Alberta Innovates, and the Canadian Red Cross (#381288).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee for Psychology and Education Sciences of Laval University (protocol code 2017-030 Phase II, date of approval: 7 November 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

S.B. is President and shareholder of Cliniques et Développement In Virtuo, a clinic that offers psychotherapy services and distributes virtual reality software. All of this is framed by the conflict of interest management policy of the Université du Québec en Outaouais. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Benevolenza, M.A.; DeRigne, L. The impact of climate change and natural disasters on vulnerable populations: A systematic review of literature. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2019, 29, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwana, N. Disaster and its impact on mental health: A narrative review. J. Fem. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, C.S.; Pfefferbaum, B. Mental health response to community disasters: A systematic review. JAMA 2013, 310, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamblen, J.L.; Norris, F.H.; Pietruszkiewicz, S.; Gibson, L.E.; Naturale, A.; Louis, C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for postdisaster distress: A community based treatment program for survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2009, 36, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, P.J.; Hamblen, J. Assisting Individuals and Communities after Natural Disasters and Community Traumas. In APA Handbook of Trauma Psychology; Cook, J., Gold, S., Dalenberg, C., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Békés, V.; Grondin, F.; Bouchard, S. Barriers and facilitators to the integration of web-based interventions into routine care. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S. Psychotherapy via videoconferencing: A review. Br. J. Guid. Counc. 2009, 37, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, D.; Eichert, H.C.; Riper, H.; Ebert, D.D. Blending face-to-face and internet-based interventions for the treatment of mental disorders in adults: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e6588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wentzel, J.; van der Vaart, R.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E. Mixing online and face-to-face therapy: How to benefit from blended care in mental health care. JMIR Ment. Health 2016, 3, e4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Connolly, S.L.; Miller, C.J.; Lindsay, J.A.; Bauer, M.S. A systematic review of providers’ attitudes toward telemental health via videoconferencing. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 27, e12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Békés, V.; Aafjes-van Doorn, K. Psychotherapists’ attitudes toward online therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Psychother. Integr. 2020, 30, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Békés, V.; Aafjes–van Doorn, K.; Prout, T.A.; Hoffman, L. Stretching the Analytic Frame: Analytic Therapists’ Experiences with Remote Therapy during COVID-19. J. Am. Psychoanal. Assoc. 2020, 68, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damianakis, T.; Climans, R.; Marziali, E. Social Workers’ Experiences of Virtual Psychotherapeutic Caregivers Groups for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Stroke, Frontotemporal Dementia, and Traumatic Brain Injury. Soc. Work Groups 2008, 31, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humer, E.; Stippl, P.; Pieh, C.; Pryss, R.; Probst, T. Experiences of Psychotherapists with Remote Psychotherapy during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-sectional Web-Based Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Vaart, R.; Witting, M.; Riper, H.; Kooistra, L.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; van Gemert-Pijnen, L.J. Blending online therapy into regular face-to-face therapy for depression: Content, ratio and preconditions according to patients and therapists using a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cioffi, V.; Cantone, D.; Guerriera, C.; Architravo, M.; Mosca, L.L.; Sperandeo, R.; Moretto, E.; Longobardi, T.; Alfano, Y.M.; Continisio, G.I.; et al. Satisfaction degree in the using of videoconferencing psychotherapy in a sample of Italian psychotherapists during Covid-19 emergency. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Infocommunications (CogInfoCom), Mariehamn, Finland, 23–25 September 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttman-Shwartz, O.; Shaul, K. Online therapy in a shared reality: The novel coronavirus as a test case. Traumatology 2021, 27, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, K.; Gold, S.; Shearer, E.M. Identifying and addressing mental health providers’ perceived barriers to clinical video telehealth utilization. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topooco, N.; Riper, H.; Araya, R.; Berking, M.; Brunn, M.; Chevreul, K.; Cieslak, R.; Ebert, D.D.; Etchmendy, E.; Herrero, R.; et al. Attitudes towards digital treatment for depression: A European stakeholder survey. Internet Interv. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambling, M.; King, R.; Reid, W.; Wegner, K. Online counselling: The experience of counsellors providing synchronous single-session counselling to young people. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2008, 8, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.M.; Jensen-Doss, A. Computer-Assisted Therapies: Examination of Therapist-Level Barriers to Their Use. Behav. Ther. 2013, 44, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, J.; Nordin, S.; Carlbring, P. Therapists’ Experiences of Conducting Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Online vis-à-vis Face-to-Face. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2015, 44, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Norwood, C.; Moghaddam, N.G.; Malins, S.; Sabin-Farrell, R. Working alliance and outcome effectiveness in videoconferencing psychotherapy: A systematic review and noninferiority meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2018, 25, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchard, S.; Allard, M.; Robillard, G.; Dumoulin, S.; Guitard, T.; Loranger, C.; Green-Demers, I.; Marchand, A.; Renaud, P.; Cournoyer, L.-G.; et al. Videoconferencing Psychotherapy for Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia: Outcome and Treatment Processes from a Non-randomized Non-inferiority Trial. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, S.; Marchand, A.; Bouchard, S.; Gosselin, P.; Langlois, F.; Belleville, G.; Dugas, M.J. Telepsychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder: Impact on the working alliance. J. Psychother. Integr. 2020, 30, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucala, M.; Schnur, J.B.; Brackman, E.H.; Constantino, M.J.; Montgomery, G.H. Clinicians’ attitudes toward therapeutic alliance in e-therapy. J. General Psychol. 2013, 140, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roesler, C. Tele-analysis: The use of media technology in psychotherapy and its impact on the therapeutic relationship. J. Anal. Psychol. 2017, 62, 372–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, R.J.; Mecham, M.R.; Vasilj, I.; Lengerich, A.J.; Brown, H.M.; Simpson, N.B.; Newsome, B.D. The effects of telepsychology format on empathic accuracy and the therapeutic alliance: An analogue counselling session. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2016, 16, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, D.C.; Gibson, K.; O’Donnell, S. To use or not to use: Clinicians’ perceptions of telemental health. Can. Psychol. 2011, 52, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machluf, R.; Abba Daleski, M.; Shahar, B.; Kula, O.; Bar-Kalifa, E. Couples therapists’ attitudes toward online therapy during the COVID-19 crisis. Fam. Process. 2021, 61, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrini, T.; Schiano Lomoriello, A.; Del Corno, F.; Lingiardi, V.; Salcuni, S. Psychotherapy during COVID-19: How the clinical practice of Italian psychotherapists changed during the pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 591170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korecka, N.; Rabenstein, R.; Pieh, C.; Stippl, P.; Barke, A.; Doering, B.; Gossmann, K.; Humer, E.; Probst, T. Psychotherapy by telephone or internet in Austria and Germany which CBT psychotherapists rate it more comparable to face-to-face psychotherapy in personal contact and have more positive actual experiences compared to previous expectations? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aafjes-van Doorn, K.; Békés, V.; Prout, T.A. Grappling with our therapeutic relationship and professional self-doubt during COVID-19: Will we use video therapy again? Couns. Psychol. Q. 2020, 34, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thériault, L.; Belleville, G.; Ouellet, M.C.; Morin, C.M. The experience and perceived consequences of the 2016 Fort McMurray fires and evacuation. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 641151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belleville, G.; Ouellet, M.-C.; Lebel, J.; Ghosh, S.; Morin, C.M.; Bouchard, S.; Guay, S.; Bergeron, N.; Campbell, T.; MacMaster, F.P. Psychological Symptoms Among Evacuees From the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires: A Population-Based Survey One Year Later. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belleville, G.; Ouellet, M.C.; Békés, V.; Lebel, J.; Morin, C.M.; Bouchard, S.; Guay, S.; Bergeron, N.; Ghosh, S.; Campbell, T.; et al. Efficacy of an online treatment targeting PTSD, depression and insomnia after a disaster: A randomized controlled trial. 2022; Under review. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, D.W.; Shamdasani, P.N. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Keane, T.M.; Palmieri, P.A.; Marx, B.P.; Schnurr, P.P. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). The National Center for PTSD. 2011. Available online: www.ptsd.va.gov (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M.; Belleville, G.; Bélanger, L.; Ivers, H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 2011, 34, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Békés, V.; Belleville, G.; Lebel, J.; Ouellet, M.-C.; Morin, C.M.; Bergeron, N.; Campbell, T.; Ghosh, S.; Bouchard, S.; Guay, S.; et al. L’expérience des thérapeutes concernant un auto-traitement guidé en ligne visant à promouvoir la résilience après une catastrophe naturelle [Therapist experiences about an online guided self-help intervention to promote resilience after a natural disaster]. Rev. Francoph. Comport. Cogn. 2020, 25, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel, J.; Flores-Tremblay, T.; Binet, É.; Ouellet, M.C.; Belleville, G. Usage Data of an Online Multidimensional Treatment to Promote Resilience After a Disaster. Sante Ment. Quebec 2021, 46, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, G.; Coyle, D.; Sharry, J. Engagement with online mental health interventions: An exploratory clinical study of a treatment for depression. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; pp. 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kelders, S.M.; Kok, R.N.; Ossebaard, H.C.; Van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.W.C. Persuasive system design does matter: A systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.E.; Doyle, C. Working alliance in online therapy as compared to face-to-face therapy: Preliminary results. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2002, 5, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johansson, O.; Michel, T.; Andersson, G.; Paxling, B. Experiences of non-adherence to Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy: A qualitative study. Internet Interv. 2015, 2, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grondin, F.; Lomanowska, A.M.; Jackson, P.L. Empathy in computer-mediated interactions: A conceptual framework for research and clinical practice. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 26, e12298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondin, F.; Lomanowska, A.M.; Békés, V.; Jackson, P.L. A methodology to improve eye contact in telepsychotherapy via videoconferencing with considerations for psychological distance. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2021, 34, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titzler, I.; Saruhanjan, K.; Berking, M.; Riper, H.; Ebert, D.D. Barriers and facilitators for the implementation of blended psychotherapy for depression: A qualitative pilot study of therapists’ perspective. Internet Interv. 2018, 12, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Békés, V.; Aafjes-van Doorn, K.; Zilcha-Mano, S.; Prout, T.A.; Hoffman, L. Psychotherapists’ Acceptance of Online Therapy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Machine Learning Approach. J. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 28, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossley, M.L. Childbirth, complications and the illusion of ‘choice’: A case study. Fem. Psychol. 2007, 17, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).