Postpartum Relapse in Patients with Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

:1. Introduction

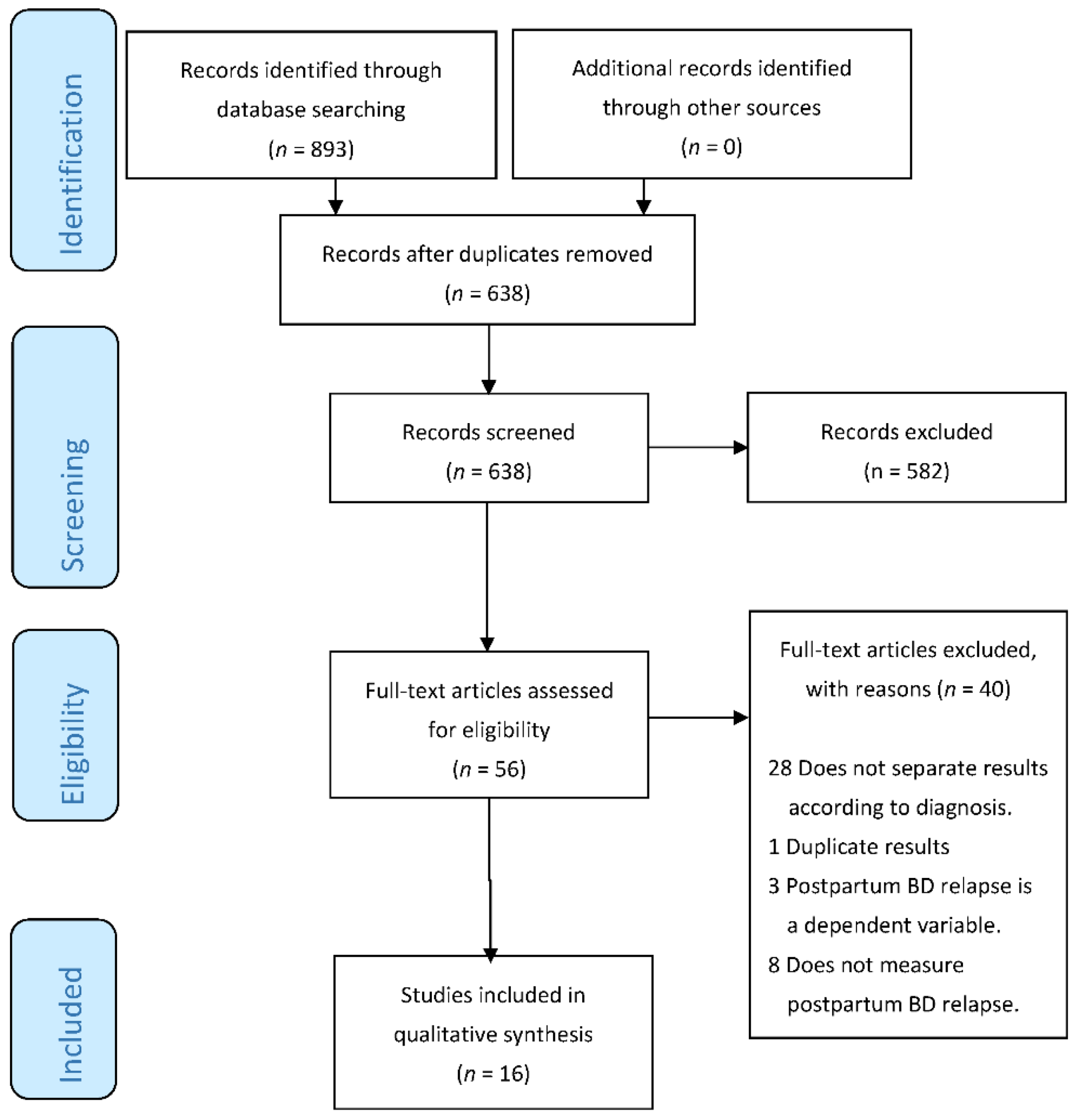

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subsection

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction Process for Each Study

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Characteristics

3.3. Subtype Episode

3.4. Pregnancy and Childbirth

3.5. Factors Associated with Postpartum Relapse

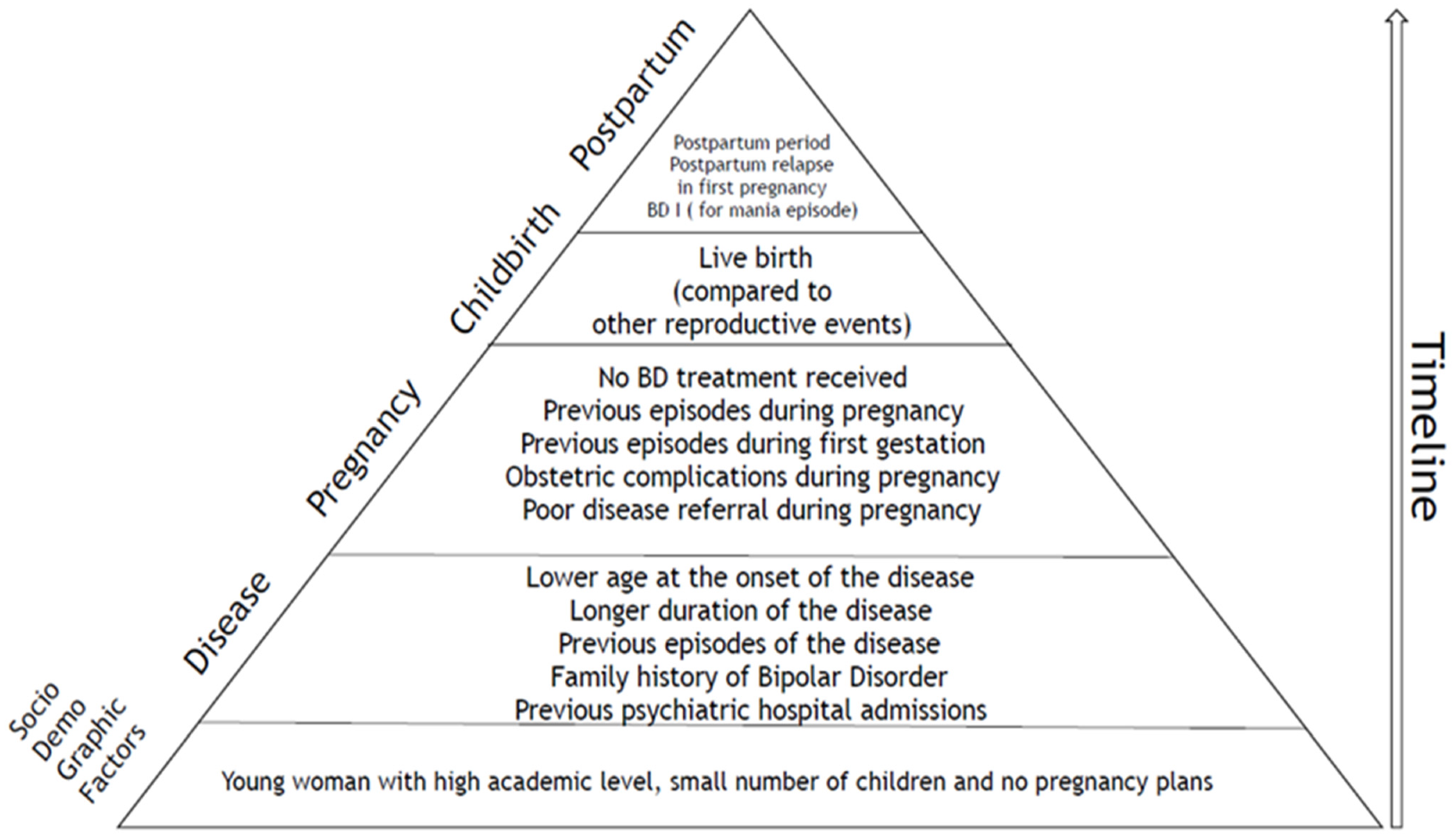

3.5.1. Sociodemographic Factors

3.5.2. Clinical Factors

4. Discussion

- −

- −

- Retrospective studies: These are the most abundant, with biases that can be inferred from this methodology, as they certainly do not detect all relapses. Of the 16 studies selected, only 5 were not retrospective, which additionally presented a reduced sample of patients (201 patients in total).

- −

- Duration of the postpartum period: This is highly variable among the different studies, ranging from 1 to 9 months, which can have a determining influence on the results of relapses. However, studies show that most relapses are early [48]. A broader temporal definition may be beneficial in clinical practice to cover care for mothers who experience a relapse in the following months after delivery. However, a broad definition may be problematic for studies examining the mechanism of postpartum relapse.

- −

- −

- Relapse diagnosis: This is highly conditioned by the type of retrospective study, as most of them used a retrospective assessment according to DSM or ICD criteria. Hypomanic episodes are particularly difficult to detect retrospectively from the available documentation. In that sense, studies with a more complete detection are prospective and use specific scales for BD status assessment. However, they have the bias of including the use of certain treatments as the main variable (olanzapine and valproate, respectively) [33,35].

- −

- Medication use: The choice of medication strategies is heterogeneous. There is no modification in retrospective studies (and in most of them, there is no analysis of these treatments), although there are some studies in which the usual treatment is modified. Analyzing the results of our review and of recent works that have studied the possible teratogenic effects of mood stabilizers, we believe that the most convenient thing to do is to continue using lithium treatment at the lowest possible dose (especially during the first trimester of pregnancy) [49], while valproic acid is completely contraindicated [50].

- −

- Sample selection: Most of the studies use samples from specialized BD programs instead of community samples.

- −

- Sample size: Most studies collected small samples. Only eight studies present a sample size greater than 100, and only two greater than 1000 deliveries [21,26]. These two studies are important and condition the final results. Di Florio et al. [21] conducted a retrospective study, but they not only relied on patient history but also complemented it with patient interviews. In this study, no considerations were made about the treatment performed. The sample obtained from cohorts was included in genetic studies of affective disorders, which could lead to a selection bias. In their results, they highlight that primiparous women with BD type I are those with the highest risk of postpartum relapse. Subsequently, Di Florio et al. were able to demonstrate that previous prenatal history of affective psychosis or depression is the most important predictor of perinatal recurrence in women with bipolar disorder [51]. Viguera et al. [26] showed a risk of relapse in mothers with BD of 3.5-times higher during postpartum than during pregnancy. The participants were selected from a Perinatal Psychiatry program, with a lower incidence of relapse than the previous study (36% vs. 45%), despite considering the postpartum for 6 months, instead of the 6 weeks considered by Di Florio. The existence of greater severity in the sample collected by this author could be considered.

- −

- Pregnancy planning: The total rate of unplanned pregnancies in BD is around 50% [52]. The risk of relapse, as well as the other risks of treatment in pregnancy, should be discussed with all women of childbearing age with mood disorders, even those who are not planning a pregnancy. Because women may not be in contact with psychiatric services, it is important that all professionals providing medical care to pregnant women, including midwives, family physicians, and obstetricians, are aware of this increased risk.

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grande, I.; Berk, M.; Birmaher, B.; Vieta, E. Bipolar disorder. Lancet 2016, 387, 1561–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Salim, M.; Sharma, V.; Anderson, K.K. Recurrence of bipolar disorder during pregnancy: A systematic review. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2018, 21, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesseloo, R.; Kamperman, A.M.; Munk-Olsen, T.; Pop, V.J.; Kushner, S.A.; Bergink, V. Risk of Postpartum Relapse in Bipolar Disorder and Postpartum Psychosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leibenluft, E. Women with bipolar illness: Clinical and research issues. Am. J. Psychiatry 1996, 153, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendell, R.E.; Chalmers, J.C.; Platz, C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munk-Olsen, T.; Laursen, T.M.; Mendelson, T.; Pedersen, C.B.; Mors, O.; Mortensen, P.B. Risks and predictors of readmission for a mental disorder during the postpartum period. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Singh, P.; Baczynski, C.; Khan, M. A closer look at the nosological status of the highs (hypomanic symptoms) in the postpartum period. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2021, 24, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Khan, M.; Corpse, C.; Sharma, P. Missed bipolarity and psychiatric comorbidity in women with postpartum depression. Bipolar Disord. 2008, 10, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.; Sharma, V. Diagnosis and treatment of postpartum bipolar depression. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2010, 10, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quevedo, L.; da Silva, R.A.; Coelho, F.; Pinheiro, K.A.T.; Horta, B.L.; Kapczinski, F.; Pinheiro, R.T. Risk of suicide and mixed episode in men in the postpartum period. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 132, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, I.; Chandra, P.S.; Dazzan, P.; Howard, L.M. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Lancet 2014, 384, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffi, E.R.; Nonacs, R.; Cohen, L.S. Safety of Psychotropic Medications During Pregnancy. Clin. Perinatol. 2019, 46, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, L.; Mortensen, P.B.; Faragher, E.B. Suicide and other causes of mortality after post-partum psychiatric admission. Br. J. Psychiatry 1998, 173, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergink, V.; Bouvy, P.F.; Vervoort, J.S.P.; Koorengevel, K.M.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Kushner, S.A. Prevention of postpartum psychosis and mania in women at high risk. Am. J. Psychiatry 2012, 169, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, T.M.; Munk-Olsen, T. Reproductive patterns in psychotic patients. Schizophr. Res. 2010, 121, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusner, M.; Berg, M.; Begley, C. Bipolar disorder in pregnancy and childbirth: A systematic review of outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; 10th Revision (ICD-10); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio, A.; Jones, L.; Forty, L.; Gordon-Smith, K.; Blackmore, E.R.; Heron, J.; Craddock, N.; Jones, I. Mood disorders and parity—A clue to the aetiology of the postpartum trigger. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 152–154, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akdeniz, F.; Vahip, S.; Pirildar, S.; Vahip, I.; Doganer, I.; Bulut, I. Risk factors associated with childbearing-related episodes in women with bipolar disorder. Psychopathology 2003, 36, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grof, P.; Robbins, W.; Alda, M.; Berghoefer, A.; Vojtechovsky, M.; Nilsson, A.; Robertson, C. Protective effect of pregnancy in women with lithium-responsive bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 61, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, G.; Rosso, G.; Aguglia, A.; Bogetto, F. Recurrence rates of bipolar disorder during the postpartum period: A study on 276 medication-free Italian women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2014, 17, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, K.; Heron, J.; Berrisford, G.; Whitmore, J.; Jones, L.; Wainscott, G.; Oyebode, F. The management of bipolar disorder in the perinatal period and risk factors for postpartum relapse. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viguera, A.C.; Tondo, L.; Koukopoulos, A.E.; Reginaldi, D.; Lepri, B.; Baldessarini, R.J. Episodes of mood disorders in 2252 pregnancies and postpartum periods. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harlow, B.L.; Vitonis, A.F.; Sparen, P.; Cnattingius, S.; Joffe, H.; Hultman, C.M. Incidence of hospitalization for postpartum psychotic and bipolar episodes in women with and without prior prepregnancy or prenatal psychiatric hospitalizations. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cohen, L.S.; Sichel, D.A.; Robertson, L.M.; Heckscher, E.; Rosenbaum, J.F. Postpartum prophylaxis for women with bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152, 1641–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilden, J.; Poels, E.M.P.; Lambrichts, S.; Vreeker, A.; Boks, M.P.M.; Ophoff, R.A.; Kahn, R.S.; Kamperman, A.M.; Bergink, V. Bipolar episodes after reproductive events in women with bipolar I disorder, A study of 919 pregnancies. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uguz, F.; Kirkas, A. Olanzapine and quetiapine in the prevention of a new mood episode in women with bipolar disorder during the postpartum period: A retrospective cohort study. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2021, 43, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sommerdyk, C.; Xie, B.; Campbell, K. Pharmacotherapy of bipolar II disorder during and after pregnancy. Curr. Drug Saf. 2013, 8, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, F.; Cruz, N.; Pacchiarotti, I.; Mazzarini, L.; Goikolea, J.M.; Popova, E.; Torrent, C.; Vieta, E. Postpartum bipolar episodes are not distinct from spontaneous episodes: Implications for DSM-V. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 126, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Smith, A.; Mazmanian, D. Olanzapine in the prevention of postpartum psychosis and mood episodes in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006, 8, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.; Gordon-Smith, K.; Di Florio, A.; Craddock, N.; Jones, L.; Jones, I. Mood episodes in pregnancy and risk of postpartum recurrence in bipolar disorder: The Bipolar Disorder Research Network Pregnancy Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisner, K.L.; Hanusa, B.H.; Peindl, K.S.; Perel, J.M. Prevention of postpartum episodes in women with bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 56, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Plana-Ripoll, O.; Ingstrup, K.G.; Agerbo, E.; Skjærven, R.; Munk-Olsen, T. Postpartum psychiatric disorders and subsequent live birth: A population-based cohort study in Denmark. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 35, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Endicott, J.; Robins, E. Research diagnostic criteria: Rationale and reliability. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1978, 35, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, C.T.; Wisner, K.L. Treatment of Peripartum Bipolar Disorder. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 45, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, A.; Gorun, A.; Benudis, A. Lithium Use and Non-use for Pregnant and Postpartum Women with Bipolar Disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, S. Managing bipolar disorder during pregnancy and the postpartum period: A critical review of current practice. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2020, 20, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Smith, K.; Perry, A.; Di Florio, A.; Forty, L.; Fraser, C.; Casanova Dias, M.; Warne, N.; MacDonald, T.; Craddock, N.; Jones, L.; et al. Symptom profile of postpartum and non-postpartum manic episodes in bipolar I disorder: A within-subjects study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 284, 112748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, E.R.; Saric, K. Pregnancy and bipolar disorder: The risk of recurrence when discontinuing treatment with mood stabilisers: A systematic review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2017, 29, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, J.; Robertson Blackmore, E.; McGuinness, M.; Craddock, N.; Jones, I. No «latent period» in the onset of bipolar affective puerperal psychosis. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2007, 10, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M.P. Puerperal affective psychosis: Is there a case for lithium prophylaxis? Br. J. Psychiatry 1992, 161, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Marks, M.; Wieck, A.; Hirst, D.; Campbell, I.; Checkley, S. Neuroendocrine and psychosocial mechanisms in post-partum psychosis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1993, 17, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platz, C.; Kendell, R.E. A matched-control follow-up and family study of ‘puerperal psychoses’. Br. J. Psychiatry 1988, 153, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gent, E.M.; Verhoeven, W.M. Bipolar illness, lithium prophylaxis, and pregnancy. Pharmacopsychiatry 1992, 25, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Florio, A.; Forty, L.; Gordon-Smith, K.; Heron, J.; Jones, L.; Craddock, N.; Jones, I. Perinatal episodes across the mood disorder spectrum. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fornaro, M.; Maritan, E.; Ferranti, R.; Zaninotto, L.; Miola, A.; Anastasia, A.; Murru, A.; Solé, E.; Stubbs, B.; Carvalho, A.F.; et al. Lithium Exposure During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Safety and Efficacy Outcomes. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Portilla, M.P.; Bobes, J. Preventive recommendations on the use of valproic acid in pregnant or gestational women to be very present. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2017, 10, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Florio, A.; Gordon-Smith, K.; Forty, L.; Kosorok, M.R.; Fraser, C.; Perry, A.; Bethell, A.; Craddock, N.; Jones, L.; Jones, I. Stratification of the risk of bipolar disorder recurrences in pregnancy and postpartum. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin Eroglu, M.; Lus, M.G. Impulsivity, Unplanned Pregnancies, and Contraception Among Women with Bipolar Disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batt, M.M.; Olsavsky, A.K.; Dardar, S.; St John-Larkin, C.; Johnson, R.L.; Sammel, M.D. Course of Illness and Treatment Updates for Bipolar Disorder in the Perinatal Period. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2022, 24, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patients | Origin of the Sample | Type of Study | Methods | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | N | Mean Age of Pregnant (SD) | BD I % | Instruments | Definition of the Relapse | % Relapse (TOTAL) | ||

| (Di Florio et al., 2014) [21] | 1.212 | 25.00 (5.25) | 77.1% | Participants with affective disorders | Retrospective | SCAN DSM-IV | 6 weeks | 45% (1.052/2.329) |

| (Akdeniz et al., 2003) [22] | 72 | NA | NS | Analysis of consecutive cases | Retrospective | SCID | 26 weeks | 16.3% (26/160) |

| (Grof et al., 2000) [23] | 28 | NA | 100% | Patients treated with lithium | Retrospective | RDC | 36 weeks | 25% (7/28) |

| (Maina et al., 2014) [24] | 276 | NA | 46.7% | Mood and Anxiety Unit | Retrospective | DSM-IV TR | 4 weeks | 75% (207/270) |

| (Sharma et al., 2013) [31] | 37 | NA | 0 (100% BD-II) | Study about the use of drugs during the pregnancy | Observational prospective | DMS-IV | 4 weeks | 70% (26/37) |

| (Doyle et al., 2012) [25] | 43 | 32 (5.5) | 80.8% | Perinatal Mental Health Service | Retrospective | DSM-IV | 6 weeks | 47% (20/43) |

| (Bergink et al., 2012) [15] | 41 | 33.6 (3.8) | 27% | Preventive postpartum program | Prospective | DSM-IV | 4 weeks | 22% (9/41) |

| (Viguera et al., 2011) [26] | 621 | 26.4 (4.9) | 45.6% | Perinatal Mental Health Service | Retrospective | DSM-IV | 24 weeks | 36% (403/1120) |

| (Colom et al., 2010) [32] | 200 | NA | 70.5% | Bipolar Disorder Program | Prospective | DSM-IV | 4 weeks | 39% (43/109) |

| (Harlow et al., 2007) [27] | 786 | NA | NS | Hospital Discharge and births Sweden Register (1987–2001) | Retrospective | ICD-10 | 90 days | 9% (67/786) |

| (Sharma et al., 2006) [33] | 25 | 30.3 (6.2) | 36% | Preventive study with olanzapine | Naturalistic Prospective | HRS, YMRS, DSM-IV | 4 weeks | 40% (10/25) |

| (Wisner et al., 2004) [35] | 26 | 32.4 | 61.5% | Preventive study with valproate | Simple Blind study | HRS, YMRS, BRMS, DSM-IV | 20 weeks | 69% (18/26) |

| (Cohen et al., 1995) [28] | 27 | 33.4 (4.9) | NA | Comparative study with profilactic treatment | Retrospective | DSM-III-R | 12 weeks | 33% (9/27) |

| (Perry et al., 2021) [34] | 124 | BD-I/SAD-BD: 34 (6) BD-II/BD-OS: 32(7) | 76.61% | Bipolar Disorder Research Network Pregnancy Study | Prospective | DSM 5 ICD-10 SCAN | 12 weeks | BD-I/SA-BD: 40.6% (39/96) BD-II/BD-OS: 44.0% (11/25) |

| (Gilden et al., 2021) [29] | 436 | NA | 100% | Bipolar cohort from Netherland | Retrospective | SCID | 24 weeks | 30.1% (277/919) |

| (Uguz et al., 2021) [30] | 23 | 30.39 (4.42) | 69.6% | Comparative study between two antipsychotics (olanzapine and quetiapine) | Retrospective | SCID | 32 weeks | 26.1% (6/23) |

| TOTAL | 3977 | 26.30 | 69.83% | 36.77% (2230/6064) | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Conejo-Galindo, J.; Sanz-Giancola, A.; Álvarez-Mon, M.Á.; Ortega, M.Á.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, L.; Lahera, G. Postpartum Relapse in Patients with Bipolar Disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3979. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11143979

Conejo-Galindo J, Sanz-Giancola A, Álvarez-Mon MÁ, Ortega MÁ, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Lahera G. Postpartum Relapse in Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(14):3979. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11143979

Chicago/Turabian StyleConejo-Galindo, Javier, Alejandro Sanz-Giancola, Miguel Ángel Álvarez-Mon, Miguel Á. Ortega, Luis Gutiérrez-Rojas, and Guillermo Lahera. 2022. "Postpartum Relapse in Patients with Bipolar Disorder" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 14: 3979. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11143979

APA StyleConejo-Galindo, J., Sanz-Giancola, A., Álvarez-Mon, M. Á., Ortega, M. Á., Gutiérrez-Rojas, L., & Lahera, G. (2022). Postpartum Relapse in Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(14), 3979. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11143979