The Short-Term Kinetics of sICAM-1 after Induction of Acute Experimental Pain in Healthy Volunteers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1, ICAM-1

1.2. Soluble Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1, sICAM-1

2. Materials and Methods

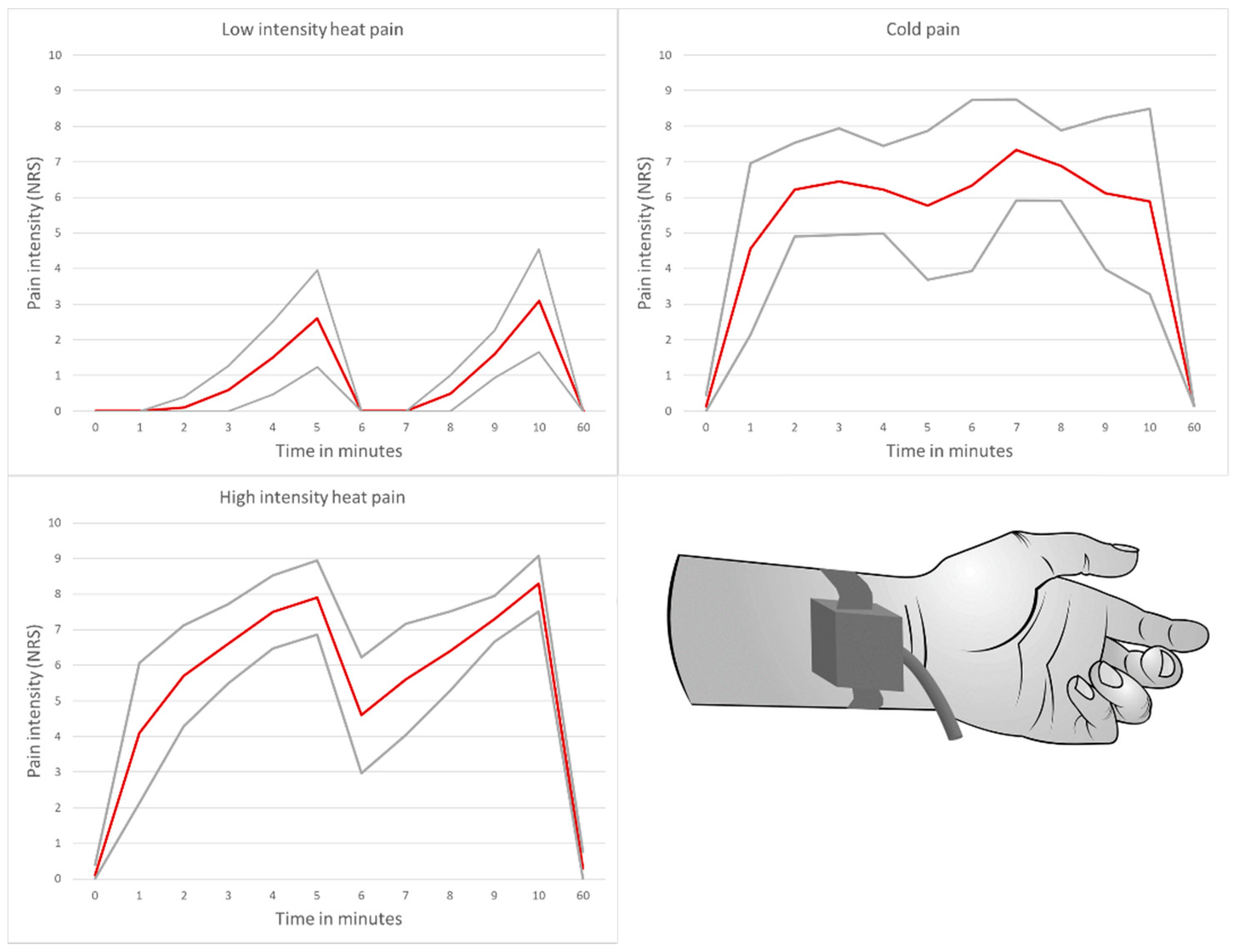

2.1. Acute Pain Model

- Low-intensity heat pain model with application of a placebo cream

- High-intensity heat pain model with application of a capsaicin cream

- Cold pain model with application of a placebo cream

- Induction of a significant pain stimulus with an average perceived pain intensity of ≥6 on a numerical rating scale in the high-intensity heat pain and cold pain model over a test duration of 10 min

- High tolerance of the pain model by the study participants

- Avoidance of severe or irreversible tissue damage

2.1.1. Test Preparation

2.1.2. Low-Intensity Heat Pain Model

2.1.3. High-Intensity Heat Pain Model

2.1.4. Cold Pain Model

2.2. Subjects

2.3. Blinding

2.4. Assessment

2.5. Cytokine Measurement

2.6. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Pain Intensity and Duration

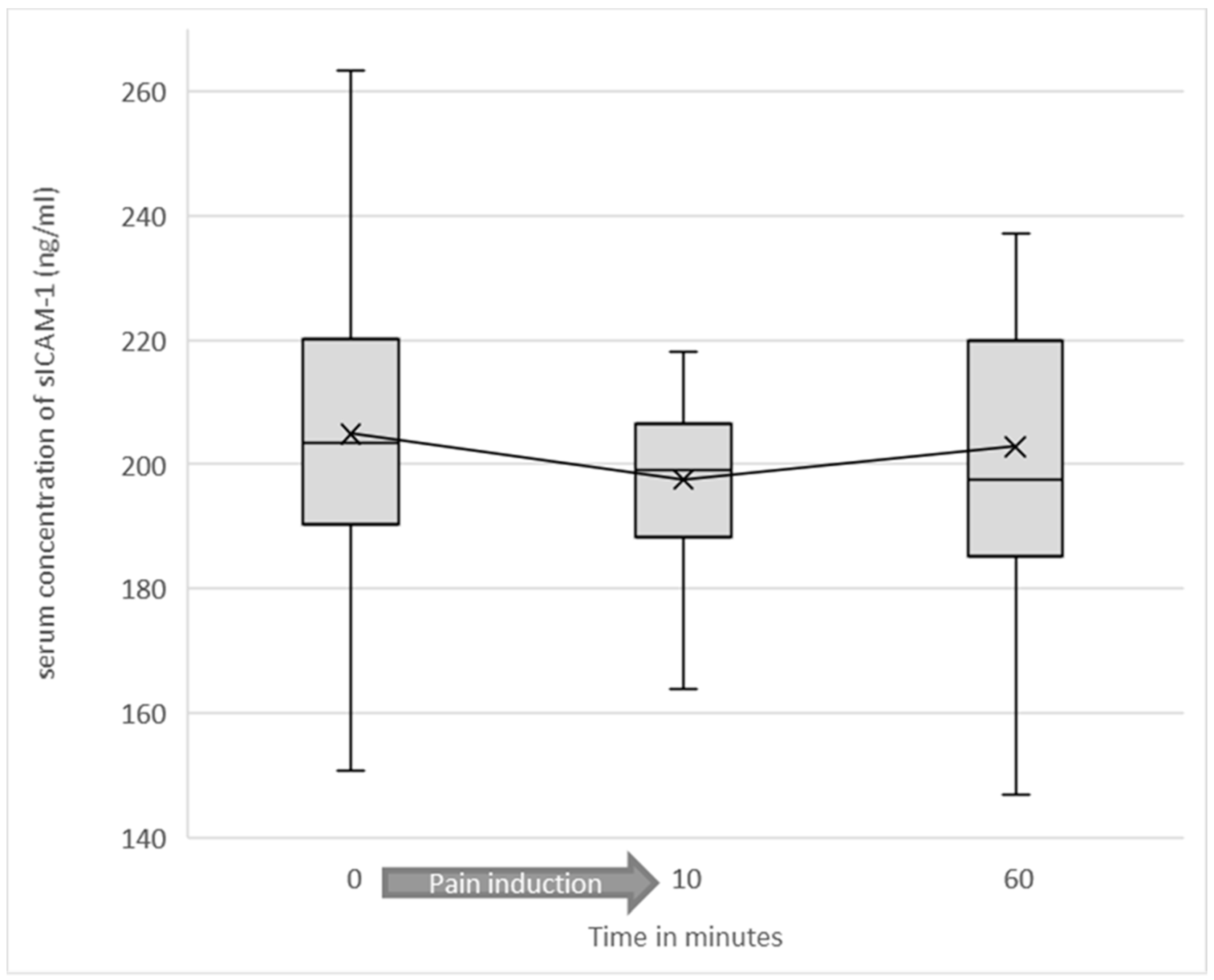

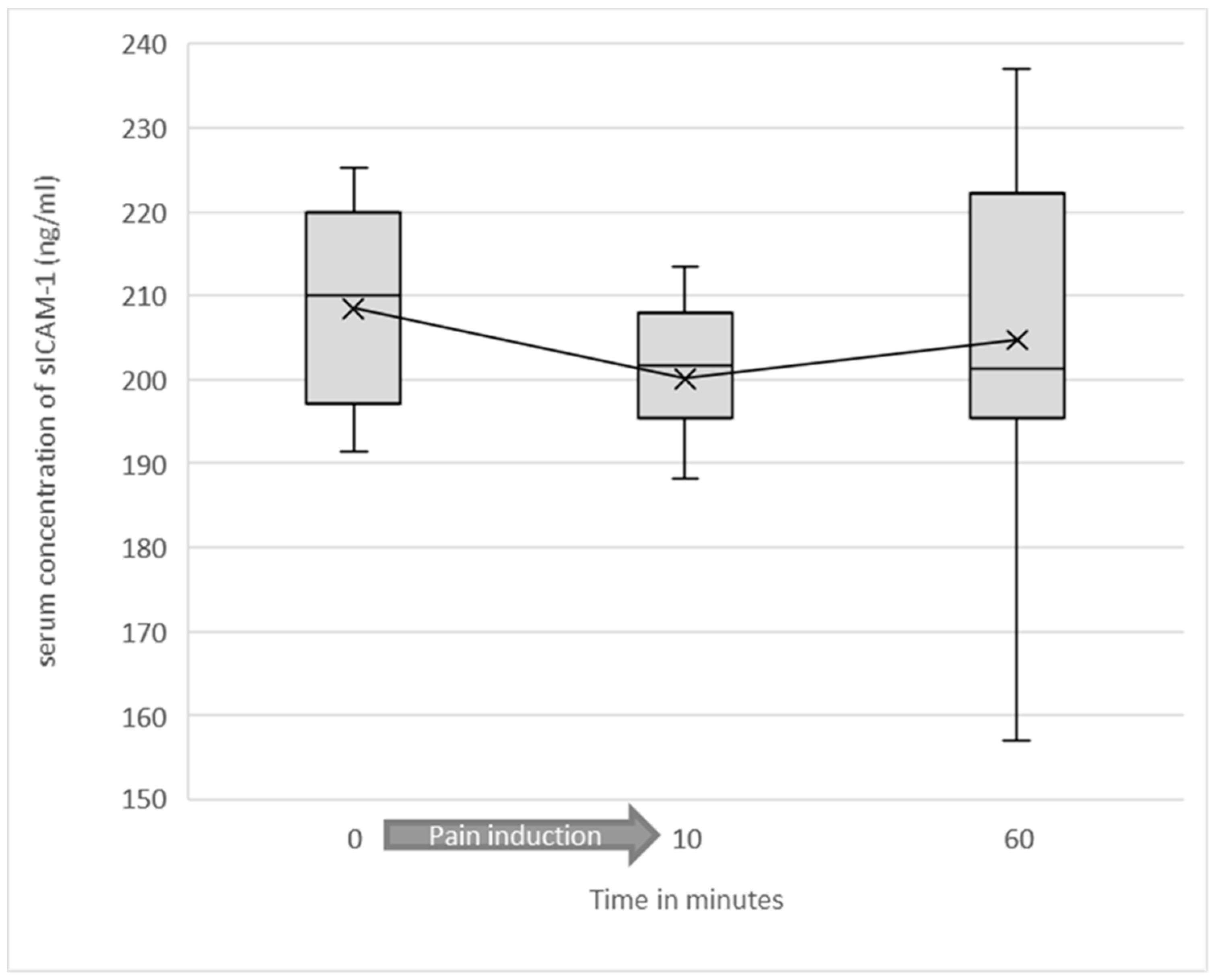

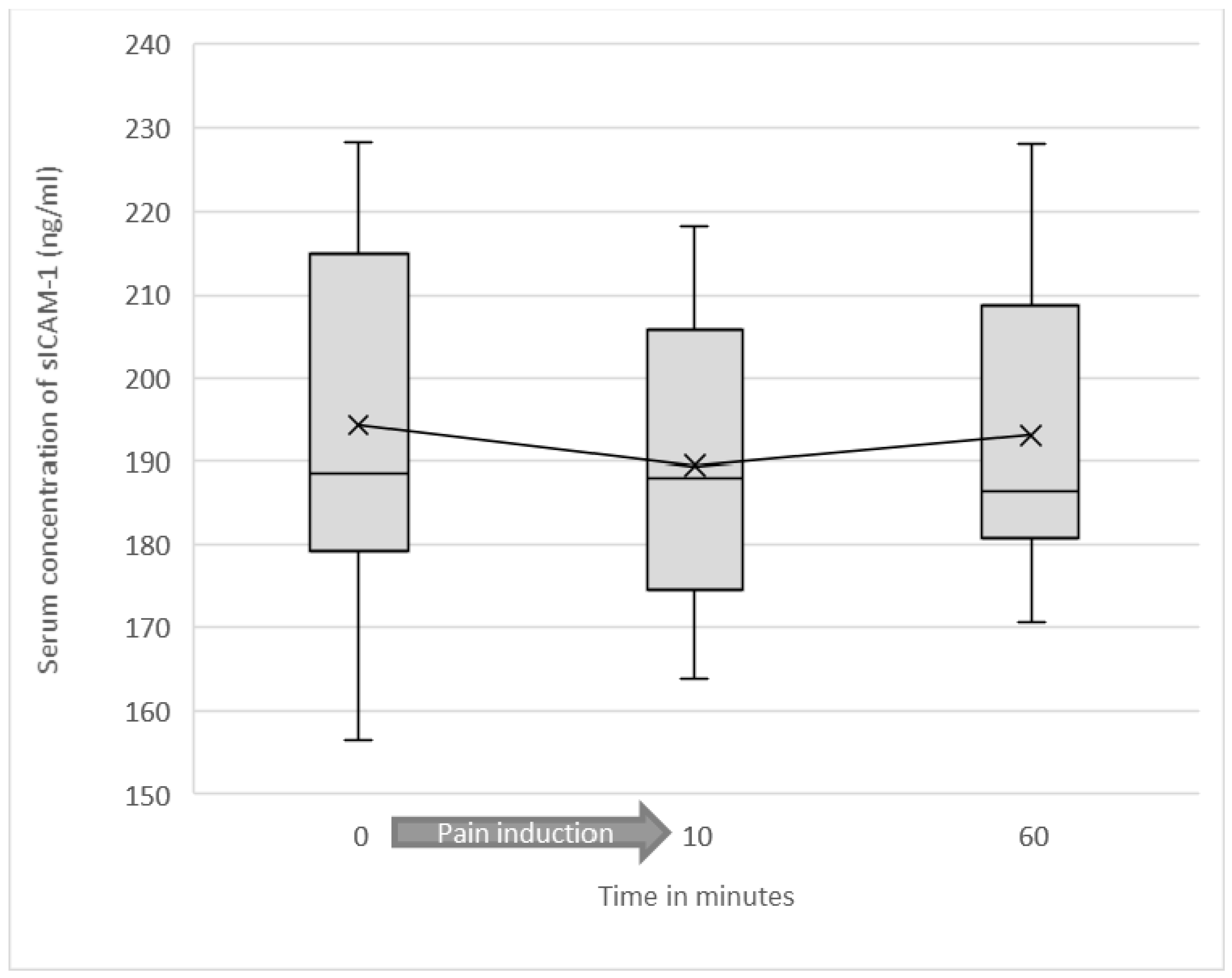

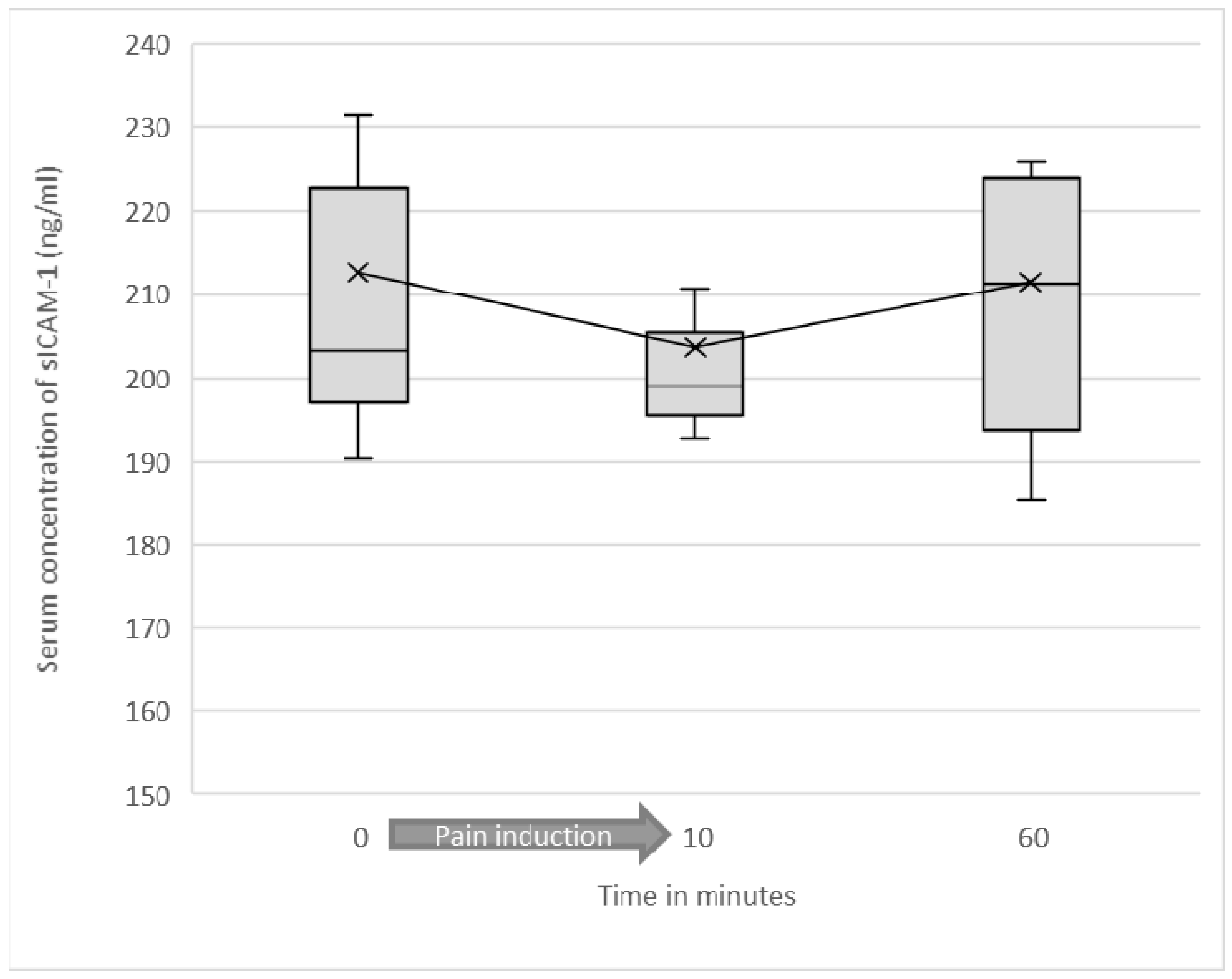

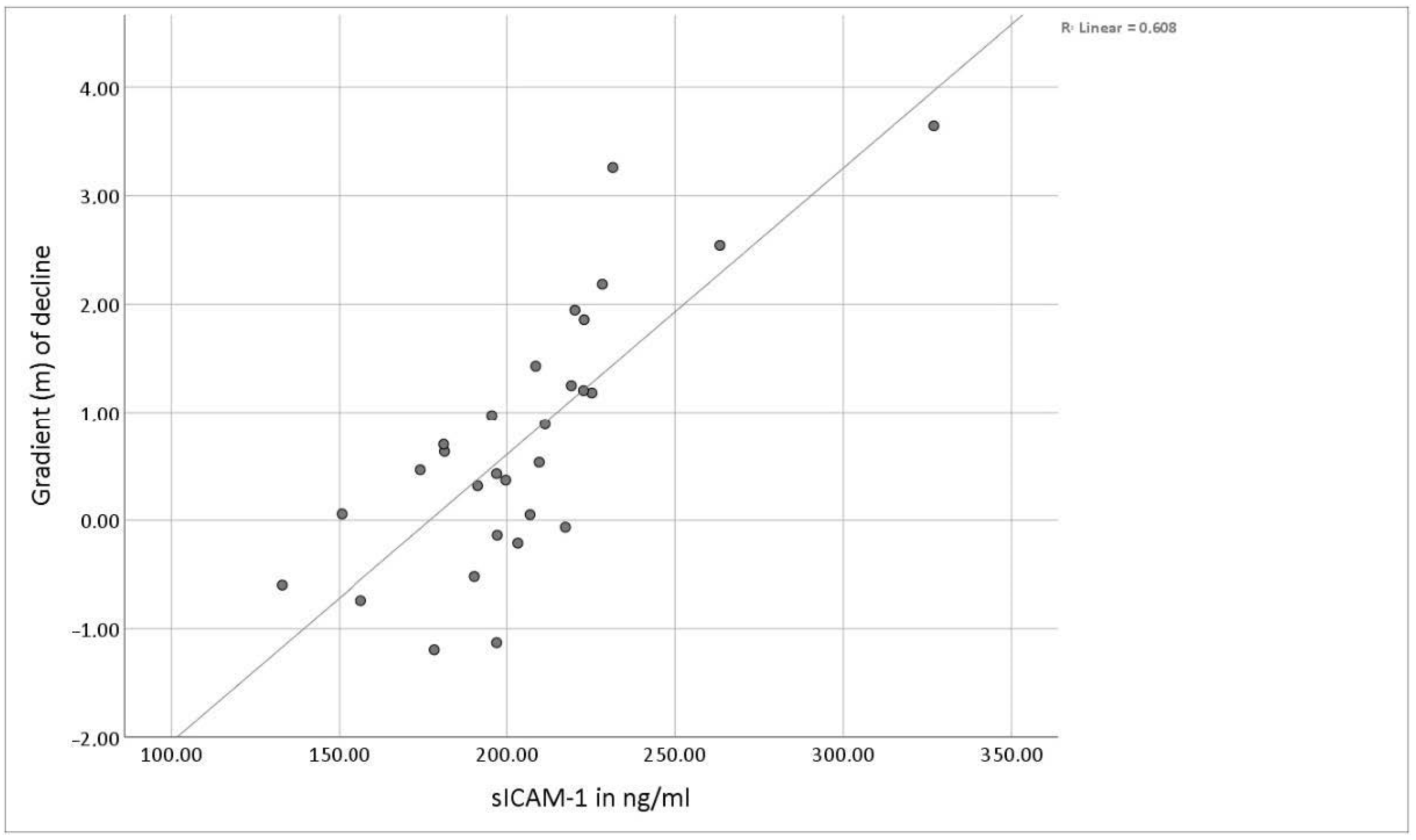

3.2. Serum Levels of Soluble ICAM-1

3.3. Sex-Related Differences

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Price, D.D.; Bush, F.M.; Long, S.; Harkins, S.W. A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. Pain 1994, 56, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjermstad, M.J.; Fayers, P.M.; Haugen, D.F.; Caraceni, A.; Hanks, G.W.; Loge, J.H.; Fainsinger, R.; Aass, N.; Kaasa, S. Studies Comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for Assessment of Pain Intensity in Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 41, 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkin, R.L.; Barkin, S.J.; Barkin, D.S. Perception, Assessment, Treatment, and Management of Pain in the Elderly. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2005, 21, 465–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwakhalen, S.M.G.; Hamers, J.P.H.; Abu-Saad, H.H.; Berger, M.P.F. Pain in elderly people with severe dementia: A systematic review of behavioural pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatr. 2006, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angst, M.S.; Clark, J.D.; Carvalho, B.; Tingle, M.; Schmelz, M.; Yeomans, D.C. Cytokine profile in human skin in response to experimental inflammation, noxious stimulation, and administration of a COX-inhibitor: A microdialysis study. Pain 2008, 139, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowen, R.; Stasiowska, M.K.; Laycock, H.; Bantel, C. Assessing pain objectively: The use of physiological markers. Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 828–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, A.; Zacharowski, K.; Boehm, O.; Stevens, M.; Markus, F.; Lipfert, P.; Von Giesen, H.-J.; Wolf, A.; Freynhagen, R. Nitric oxide and pro-inflammatory cytokines correlate with pain intensity in chronic pain patients. Inflamm. Res. 2007, 56, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.M.; Peterlin, B.L.; Perreault, M.J.; Grothusen, J.R.; Schwartzman, R.J. Changes in Plasma Cytokines and Their Soluble Receptors in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. J. Pain 2012, 13, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Bennett, D.L.H. Neuroinflammation and the generation of neuropathic pain. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.G.; Duffy, S.S.; Moalem-Taylor, G. Immunotherapy targeting cytokines in neuropathic pain. Front. Pharmacol. 2013, 4, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchting, B.; Hinske, L.C.G.; Rachinger-Adam, B.; Celi, L.A.; Kreth, S.; Azad, S.C. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1: A potential biomarker for pain intensity in chronic pain patients. Biomarkers Med. 2017, 11, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousoulis, D.; Daves, G.J.; Asimakopoulos, G.; Homaei, H.; Zouridakis, E.; Ahmed, N.; Kaski, J.C. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 serum level in patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteries (syndrome X). Clin. Cardiol. 2001, 24, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; He, Q.; Ren, Z.; Li, F.; Chen, W.; Lin, X.; Zhang, H.; Tai, G. Association of serum levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and interleukin-6 with migraine. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 36, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staunton, D.E.; Marlin, S.D.; Stratowa, C.; Dustin, M.L.; Springer, T.A. Primary structure of ICAM-1 demonstrates interaction between members of the immunoglobulin and integrin supergene families. Cell 1988, 52, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.W.; Marlin, S.D.; Rothlein, R.; Toman, C.; Anderson, D.C. Cooperative interactions of LFA-1 and Mac-1 with intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in facilitating adherence and transendothelial migration of human neutrophils in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 1989, 83, 2008–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Mousa, S. Morphological correlates of immune-mediated peripheral opioid analgesia. Single Mol. Single Cell Seq. 2003, 521, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, C.; Hassan, A.H.; Przewlocki, R.; Gramsch, C.; Peter, K.; Herz, A. Opioids from immunocytes interact with receptors on sensory nerves to inhibit nociception in inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 5935–5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S.; Hermanussen, S.; Tang, L.; Monteith, G.R.; Cabot, P.J. The Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule Antibody Blocks Cold Water Swim Stress-Induced Analgesia and Cell Adhesion between Lymphocytes and Cultured Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurons. Anesth. Analg. 2006, 103, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, O.; Papaioannou, A.; Ochietti, B.; Beauchemin, C.; Legault, D.; Cantin, A.; King, P.D.; Daniel, C.; Alakhov, V.Y.; Potworowski, E.F.; et al. ICAM-1 isoforms: Specific activity and sensitivity to cleavage by leukocyte elastase and cathepsin G. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003, 33, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, E.; Fusco, C.; Romero, P.; Stamenkovic, I. Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9/gelatinase B) proteolytically cleaves ICAM-1 and participates in tumor cell resistance to natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Oncogene 2002, 21, 5213–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakadze, N.L.; Sithu, S.D.; Sen, U.; English, W.R.; Murphy, G.; D’Souza, S.E. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α-converting Enzyme (TACE/ADAM-17) Mediates the Ectodomain Cleavage of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1). J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 3157–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithu, S.D.; English, W.R.; Olson, P.; Krubasik, D.; Baker, A.H.; Murphy, G.; D’Souza, S.E. Membrane-type 1-Matrix Metalloproteinase Regulates Intracellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1)-mediated Monocyte Transmigration. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25010–25019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorelli, M.; De Blasi, A.; DeFazio, G.; Avolio, C.; Iacovelli, L.; Livrea, P.; Trojano, M. Differential Regulation of Membrane Bound and Soluble ICAM 1 in Human Endothelium and Blood Mononuclear Cells: Effects of Interferon Beta-1a. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2002, 9, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Leeuwenberg, J.F.; Smeets, E.F.; Neefjes, J.J.; A Shaffer, M.; Cinek, T.; Jeunhomme, T.M.; Ahern, T.J.; A Buurman, W. E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 are released by activated human endothelial cells in vitro. Immunology 1992, 77, 543–549. [Google Scholar]

- Lüke, P.; Luchting, B.; Kraft, E.; Azad, S.C. Etablierung eines adaptierbaren Akutschmerzmodells zur Induktion nozizeptiver Stimuli definierter Intensität und Dauer mittels thermischer Reize. Schmerz 2020, 34, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flühr, K.; Neddermeyer, T.J.; Lötsch, J. Capsaicin or Menthol Sensitization Induces Quantitative But No Qualitative Changes to Thermal and Mechanical Pain Thresholds. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Basler, H.-D. Kurzfragebogen zur Aktuellen Beanspruchung: KAB; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, J.L., 3rd; Robinson, M.E.; Wise, E.A.; Myers, C.D.; Fillingim, R.B. Sex differences in the perception of noxious experimental stimuli: A meta-analysis. Pain 1998, 74, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, A.M.; Borawska, M.H. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1): An overview. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2004, 15, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, C.; Wolf, S. ICAM-1 signaling in endothelial cells. Pharmacol. Rep. 2009, 61, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caterina, M.J.; Schumacher, M.A.; Tominaga, M.; Rosen, T.A.; Levine, J.D.; Julius, D. The capsaicin receptor: A heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 1997, 389, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peier, A.M.; Moqrich, A.; Hergarden, A.C.; Reeve, A.J.; Andersson, D.A.; Story, G.M.; Earley, T.J.; Dragoni, I.; McIntyre, P.; Bevan, S.; et al. A TRP Channel that Senses Cold Stimuli and Menthol. Cell 2002, 108, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn-Munro, G.; Blackburn-Munro, R.E. Chronic Pain, Chronic Stress and Depression: Coincidence or Consequence? J. Neuroendocr. 2001, 13, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, E.; Hesse, J.; Hellhammer, J.; Hellhammer, D.H. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005, 30, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsigos, C.; Chrousos, G.P. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, M.; Carter, L.; Stein, C. Interleukin 1 beta and corticotropin-releasing factor inhibit pain by releasing opioids from immune cells in inflamed tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 4219–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinz, A.; Hermann, D.; Smolka, M.N.; Rieks, M.; Gräf, K.-J.; Pöhlau, D.; Kuhn, W.; Bauer, M. Effects of acute psychological stress on adhesion molecules, interleukins and sex hormones: Implications for coronary heart disease. Psychopharmacology 2003, 165, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lüke, P.; Kraft, E.; Azad, S.C. The Short-Term Kinetics of sICAM-1 after Induction of Acute Experimental Pain in Healthy Volunteers. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10092021

Lüke P, Kraft E, Azad SC. The Short-Term Kinetics of sICAM-1 after Induction of Acute Experimental Pain in Healthy Volunteers. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(9):2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10092021

Chicago/Turabian StyleLüke, Philipp, Eduard Kraft, and Shahnaz Christina Azad. 2021. "The Short-Term Kinetics of sICAM-1 after Induction of Acute Experimental Pain in Healthy Volunteers" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 9: 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10092021

APA StyleLüke, P., Kraft, E., & Azad, S. C. (2021). The Short-Term Kinetics of sICAM-1 after Induction of Acute Experimental Pain in Healthy Volunteers. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(9), 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10092021