GABA Supplementation Negatively Affects Cognitive Flexibility Independent of Tyrosine

Abstract

1. Introduction

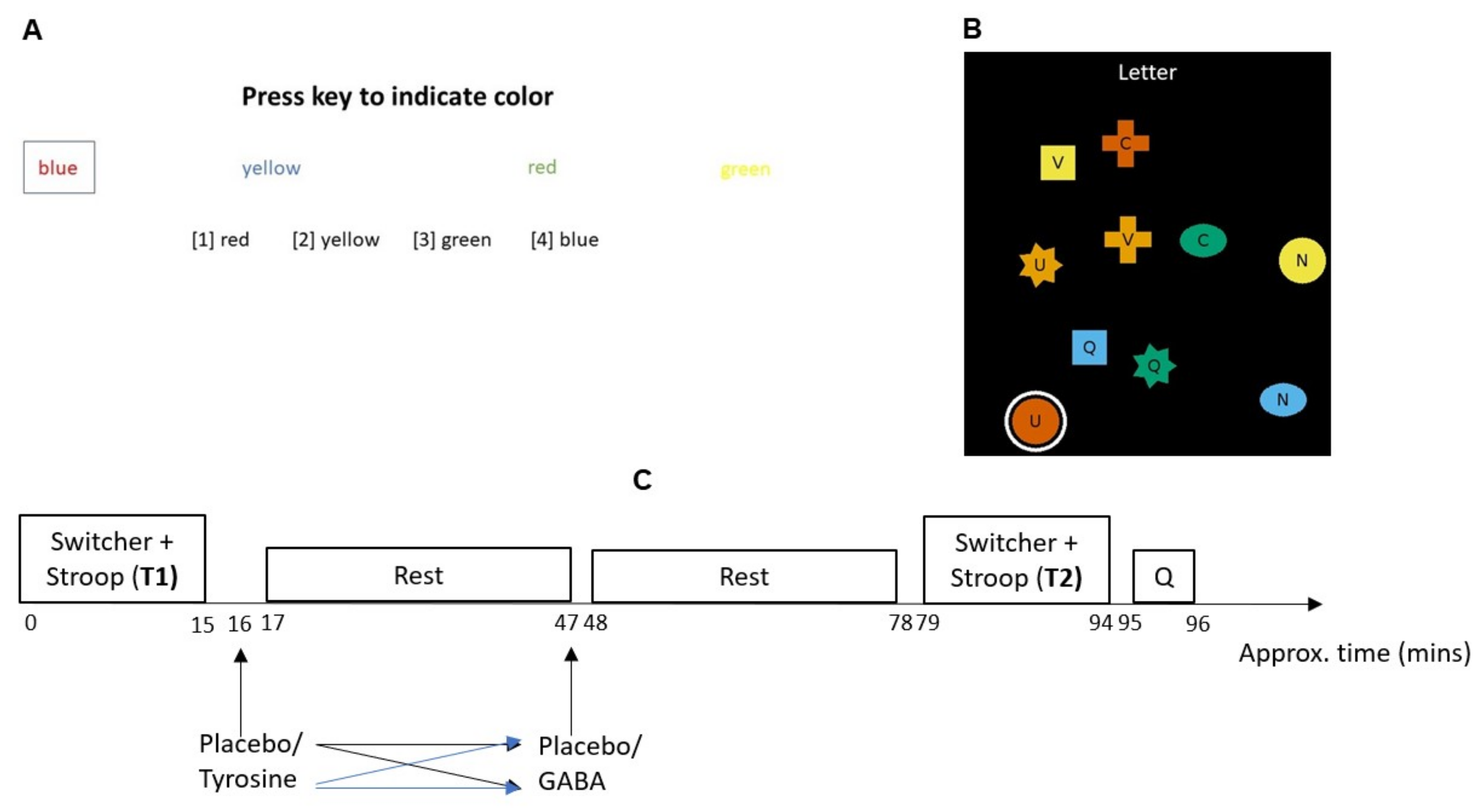

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Drug Administration

3. Cognitive Flexibility Tasks

4. Procedures

5. Data Analysis

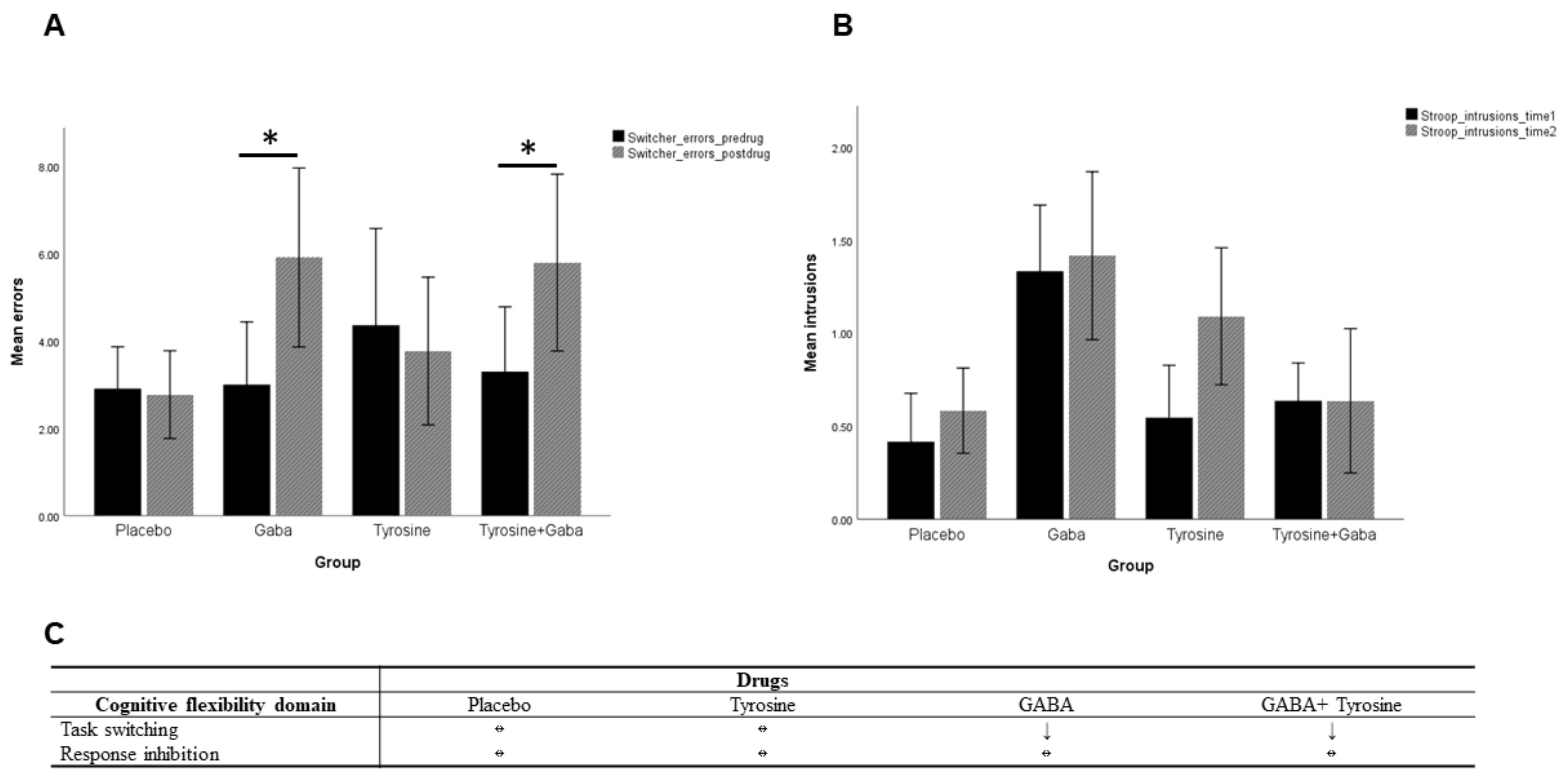

6. Results

6.1. Switcher Task

6.2. Victoria Stroop Task

6.3. Double Blinding of the Drug Administration

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chamberlain, S.R.; Solly, J.E.; Hook, R.W.; Vaghi, M.M.; Robbins, T.V. Cognitive Inflexibility in OCD and Related Disorders; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 1–21.

- Hatzipantelis, C.J.; Langiu, M.; Vandekolk, T.H.; Pierce, T.L.; Nithianantharajah, J.; Stewart, G.D.; Langmead, C.J. Translation-Focused Approaches to GPCR Drug Discovery for Cognitive Impairments Associated with Schizophrenia. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 3, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pehrson, A.L.; Leiser, S.C.; Gulinello, M.; Dale, E.; Li, Y.; Waller, J.A.; Sanchez, C. Treatment of cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder—A review of the preclinical evidence for efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and the multimodal-acting antidepressant vortioxetine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 753, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danner, U.N.; Dingemans, A.E.; Steinglass, J. Cognitive remediation therapy for eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2015, 28, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo, A.; Jentsch, J.D. Reversal learning as a measure of impulsive and compulsive behavior in addictions. Psychopharmacology 2012, 219, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, L.; Pettorruso, M.; De Crescenzo, F.; De Risio, L.; di Nuzzo, L.; Martinotti, G.; Bifone, A.; Janiri, L.; Di Nicola, M. Neural correlates of cognitive control in gambling disorder: A systematic review of fMRI studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 78, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, F.; Seer, C.; Kopp, B. Cognitive flexibility in neurological disorders: Cognitive components and event-related potentials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 83, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dajani, D.R.; Uddin, L.Q. Demystifying cognitive flexibility: Implications for clinical and developmental neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2015, 38, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klanker, M.; Feenstra, M.; Denys, D. Dopaminergic control of cognitive flexibility in humans and animals. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, A.; Kopp, B. Toward a Computational Neuropsychology of Cognitive Flexibility. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, J.A. The neural underpinnings of cognitive flexibility and their disruption in psychotic illness. Neuroscience 2017, 345, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borwick, C.; Lal, R.; Lim, L.W.; Stagg, C.J.; Aquili, L. Dopamine depletion effects on cognitive flexibility as modulated by tDCS of the dlPFC. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzato, L.S.; Jongkees, B.J.; Sellaro, R.; van den Wildenberg, W.P.M.; Hommel, B. Eating to stop: Tyrosine supplementation enhances inhibitory control but not response execution. Neuropsychologia 2014, 62, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzato, L.S.; Steenbergen, L.; Sellaro, R.; Stock, A.-K.; Arning, L.; Beste, C. Effects of l-Tyrosine on working memory and inhibitory control are determined by DRD2 genotypes: A randomized controlled trial. Cortex 2016, 82, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, O.; Gao, J.; Lim, L.W.; Stagg, C.J.; Aquili, L. Catecholaminergic modulation of indices of cognitive flexibility: A pharmaco-tDCS study. Brain Stimul. 2019, 12, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, O.J.; Standing, H.R.; DeVito, E.E.; Cools, R.; Sahakian, B.J. Dopamine precursor depletion improves punishment prediction during reversal learning in healthy females but not males. Psychopharmacology 2010, 211, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Steenbergen, L.; Sellaro, R.; Hommel, B.; Colzato, L.S. Tyrosine promotes cognitive flexibility: Evidence from proactive vs. reactive control during task switching performance. Neuropsychologia 2015, 69, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, A.-K.; Colzato, L.; Beste, C. On the effects of tyrosine supplementation on interference control in a randomized, double-blind placebo-control trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrshek-Schallhorn, S.; Wahlstrom, D.; Benolkin, K.; White, T.; Luciana, M. Affective Bias and Response Modulation Following Tyrosine Depletion in Healthy Adults. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31, 2523–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lythe, K.E.; Anderson, I.M.; Deakin, J.F.W.; Elliot, R.; Strickland, P.L. Lack of behavioural effects after acute tyrosine depletion in healthy volunteers. J. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 19, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdani, C.; Vidal, F.; Dagher, A.; Carbonnell, L.; Hasbroucq, T. Dopamine and response selection: An Acute Phenylalanine/Tyrosine Depletion study. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, A.; Lim, L.W.; Aquili, L. Tyrosine negatively affects flexible-like behaviour under cognitively demanding conditions. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 260, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creed, M.C.; Ntamati, N.R.; Tan, K.R. VTA GABA neurons modulate specific learning behaviors through the control of dopamine and cholinergic systems. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrier, J.; Ort, A.; Yvon, C.; Saj, A.; Vuilleumier, P.; Luscher, C. Bi-Directional Effect of Increasing Doses of Baclofen on Reinforcement Learning. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ort, A.; Kometer, M.; Rohde, J.; Seifritz, E.; Vollenweider, F.X. The role of GABAB receptors in human reinforcement learning. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, T.R.; Harper, D.; Kampman, K.; Kildea-McCrea, S.; Jens, W.; Lynch, K.G.; O’Brien, C.P.; Childress, A.R. The GABA B agonist baclofen reduces cigarette consumption in a preliminary double-blind placebo-controlled smoking reduction study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 103, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, T.R.; Wang, Z.; Sciortino, N.; Harper, D.; Li, Y.; Hakun, J.; Kildea, S.; Kampman, K.; Ehrman, R.; Derte, J.A.; et al. Modulation of resting brain cerebral blood flow by the GABA B agonist, baclofen: A longitudinal perfusion fMRI study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 117, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, M.N.; Orekhov, Y.; Ziemann, U. Suppression of LTP-like plasticity in human motor cortex by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen. Exp. Brain Res. 2007, 180, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.M.; Higashiguchi, S.; Horie, K.; Kim, M.; Hatta, H.; Yokogoshi, H. Relaxation and immunity enhancement effects of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) administration in humans. BioFactors 2006, 26, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehira, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Horie, K.; Horie, H.; Furugori, K.; Sauchi, Y.; Yokogoshi, H. Relieving occupational fatigue by consumption of a beverage containing γ-amino butyric acid. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2011, 57, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Takishima, T.; Kometani, T.; Yokogoshi, H. Psychological stress-reducing effect of chocolate enriched with γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in humans: Assessment of stress using heart rate variability and salivary chromogranin A. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonte, A.; Colzato, L.S.; Steenbergen, L.; Hommel, B.; Akyurek, E.G. Supplementation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) affects temporal, but not spatial visual attention. Brain Cogn. 2018, 120, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen, L.; Sellaro, R.; Stock, A.-K.; Beste, C.; Colzato, L.S. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) administration improves action selection processes: A randomised controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, R.; D’Esposito, M. Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 69, e113–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bast, T.; Pezze, M.; McGarrity, S. Cognitive deficits caused by prefrontal cortical and hippocampal neural disinhibition. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 3211–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Düzel, S.; Colzato, L.; Norman, K.; Gallinat, J.; Brandmaier, A.M.; Lindenberger, U.; Widaman, K.F. Food for thought: Association between dietary tyrosine and cognitive performance in younger and older adults. Psychol. Res. 2019, 83, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soranzo, A.; Aquili, L. Fear expression is suppressed by tyrosine administration. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Perceval, G.J.; Feng, W.; Feng, C. High Cognitive Flexibility Learners Perform Better in Probabilistic Rule Learning. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongkees, B.J.; Hommel, B.; Kühn, S.; Colzato, L.S. Effect of tyrosine supplementation on clinical and healthy populations under stress or cognitive demands—A review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 70, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, E.; Sherman, E.; Spreen, O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, S.T. The PEBL Manual; Lulu Press Inc.: Morrisville, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, S.T.; Piper, B.J. The psychology experiment building language (PEBL) and PEBL test battery. J. Neurosci. Methods 2014, 222, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, A.K.; Leach, L.; Strauss, E. Aging and response inhibition: Normative data for the Victoria Stroop Test. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2006, 13, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernstrom, J.D. Aromatic amino acids and monoamine synthesis in the central nervous system: Influence of the diet. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1990, 1, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monchi, O.; Petrides, M.; Petre, V.; Worsley, K.; Dagher, A. Wisconsin Card Sorting revisited: Distinct neural circuits participating in different stages of the task identified by event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 7733–7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, G.M.; Poulsen, H.E.; Paulson, O.B. Blood-brain barrier permeability in galactosamine-induced hepatic encephalopathy: No evidence for increased GABA-transport. J. Hepatol. 1988, 6, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyama, K.; Sze, P. Blood-brain barrier to H3-γ-aminobutyric acid in normal and amino oxyacetic acid-treated animals. Neuropharmacology 1971, 10, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, E.; de Kleijn, R.; Colzato, L.S.; Alkemade, A.; Forstmann, B.U.; Nieuwenhuis, S. Neurotransmitters as food supplements: The effects of GABA on brain and behavior. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sarraf, H. Transport of 14C-γ-aminobutyric acid into brain, cerebrospinal fluid and choroid plexus in neonatal and adult rats. Dev. Brain Res. 2002, 139, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyamaladevi, N.; Jayakumar, A.R.; Sujatha, R.; Paul, V.; Subramanian, E.H. Evidence that nitric oxide production increases γ-amino butyric acid permeability of blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. Bull. 2002, 57, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanaga, H.; Ohtsuki, S.; Hosoya, K.I.; Terasaki, T. GAT2/BGT-1 as a system responsible for the transport of γ-aminobutyric acid at the mouse blood-brain barrier. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001, 21, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Choudhury, S.; Islam, N.; Chowdhury, M.S.; Chowhury, T.I.; Baker, M.R.; Baker, S.N.; Kumar, H. Effects of diazepam on reaction times to stop and go. Front. Human Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B.; Richards, J.B.; Dassinger, M.; de Wit, H. Therapeutic doses of diazepam do not alter impulsive behavior in humans. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004, 79, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheson, A.; Reynolds, B.; Richards, J.B.; de Wit, H. Diazepam impairs behavioral inhibition but not delay discounting or risk taking in healthy adults. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zessen, R.; Phillips, J.L.; Budygin, E.A.; Stuber, G.D. Activation of VTA GABA neurons disrupts reward consumption. Neuron 2012, 73, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshel, N.; Bukwich, M.; Rao, V.; Hemmelder, V.; Tian, J.; Uchida, N. Arithmetic and local circuitry underlying dopamine prediction errors. Nature 2015, 525, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Goer, F.; Murray, L.; Dillon, D.G.; Beltzer, M.L.; Cohen, A.L.; Brooks, N.H.; Pizzagalli, D.A. Impaired reward prediction error encoding and striatal-midbrain connectivity in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakova, A.O.; Knolle, F.; Justicia, A.; Bullmore, E.T.; Jones, P.B.; Robbins, T.W.; Fletcher, P.C.; Murray, G.K. Abnormal reward prediction-error signalling in antipsychotic naive individuals with first-episode psychosis or clinical risk for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvaz, M.A.; Konova, A.B.; Proudfit, G.H.; Dunning, J.P.; Malaker, P.; Moeller, S.J.; Maloney, T.; Alia-Klein, N.; Goldstein, R.Z. Impaired neural response to negative prediction errors in cocaine addiction. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 1872–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, L.W.; Aquili, L. GABA Supplementation Negatively Affects Cognitive Flexibility Independent of Tyrosine. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091807

Lim LW, Aquili L. GABA Supplementation Negatively Affects Cognitive Flexibility Independent of Tyrosine. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(9):1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091807

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Lee Wei, and Luca Aquili. 2021. "GABA Supplementation Negatively Affects Cognitive Flexibility Independent of Tyrosine" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 9: 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091807

APA StyleLim, L. W., & Aquili, L. (2021). GABA Supplementation Negatively Affects Cognitive Flexibility Independent of Tyrosine. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(9), 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10091807