Assessing the Impact of Multi-Morbidity and Related Constructs on Patient Reported Safety in Primary Care: Generalized Structural Equation Modelling of Observational Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

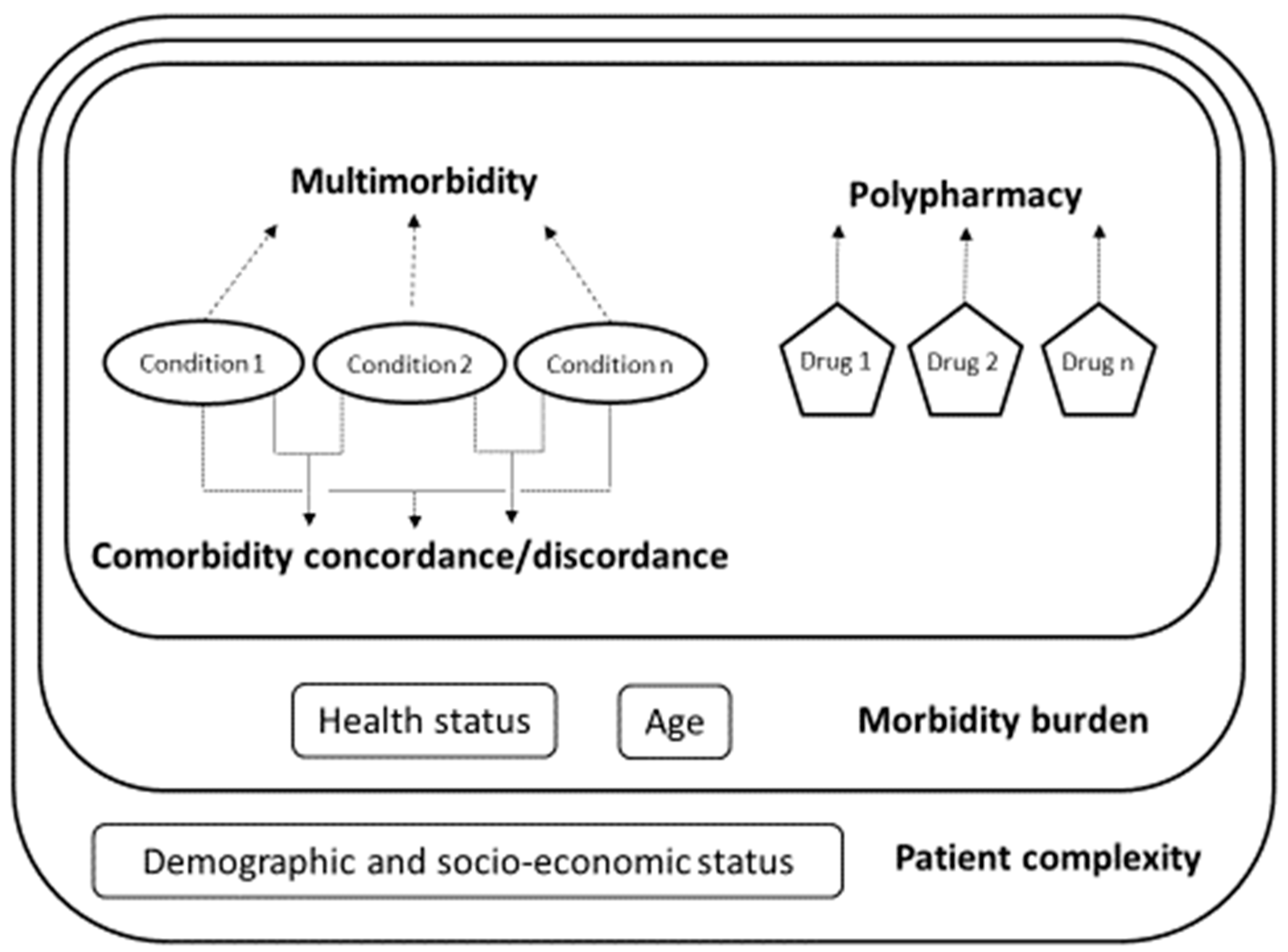

2.2. Multimorbidity and Related Constructs

- Multimorbidity and polypharmacy. We measured multimorbidity as the total number of self-reported long-term conditions for each respondent [28] (see below for the full list). Previous studies measuring self-reported multimorbidity support the validity of the self-reported approach [28,29,30,31]. Polypharmacy estimates were based on the self-reported number of prescription drugs.

- Comorbidity discordance. We classified pairs of conditions as concordant or discordant based on their pathophysiology. Concordant comorbidity was defined as a set of conditions that are part of a shared pathophysiological pathway and thereby more likely to share the same management and are more likely to be the focus of the same disease management plan (e.g., hypertension and diabetes) [22,23]. Discordant comorbidity was defined as sets of diseases that are “not directly related in either pathogenesis or management and do not share an underlying predisposing factor” (e.g., hypertension and osteoporosis). We hence classified as concordant comorbidities the following sets of conditions: cardiovascular (which included “hypertension”, “hypercholesterolemia”, “type 2 diabetes”, “long-term heart problem” and “blood circulation problems”); mental health (“depression” and “other mental health problems”) and musculoskeletal (“arthrosis and rheumatic problems” and “osteoporosis”). The rest of the conditions, including “asthma or bronchitis or emphysema”, “allergy”, “migraine or headaches”, “prostate-related problems”, “peptic or gastric ulcer”, “inguinal hernia” and “menstruation-related problems”, were not considered to be concordant with any other according to their pathophysiology. All patients with more than one condition were thus classified in terms of increasing the levels of comorbidity discordance as having (mutually exclusive, lowest-to-highest discordance): (1) fully concordant multimorbidity (100% of the conditions classified as concordant) or (2) predominantly concordant multimorbidity (at least one discordant condition and >50% of the conditions classified as concordant), predominantly discordant multimorbidity (at least one discordant condition and ≤50% of the conditions classified as concordant) and totally discordant multimorbidity (100% of conditions mutually discordant).

- Morbidity burden. We developed an index of morbidity burdens based on the previous constructs (multimorbidity (number of conditions), polypharmacy (number of medications and comorbidity discordance), and self-reported health status and age (see details in Statistical Analysis).

- Patient complexity. Finally, we constructed an index of patient complexity based on the variables included in the development of the morbidity burden and included the educational attainment, occupational status and country of origin (see details in Statistical Analysis).

2.3. Patient Safety

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Multimorbidity and Related Constructs

3.1.1. Morbidity Burden

3.1.2. Patient Complexity

3.2. Patient Safety

3.3. Association between Multimorbidity and Related Constructs and Patient Safety

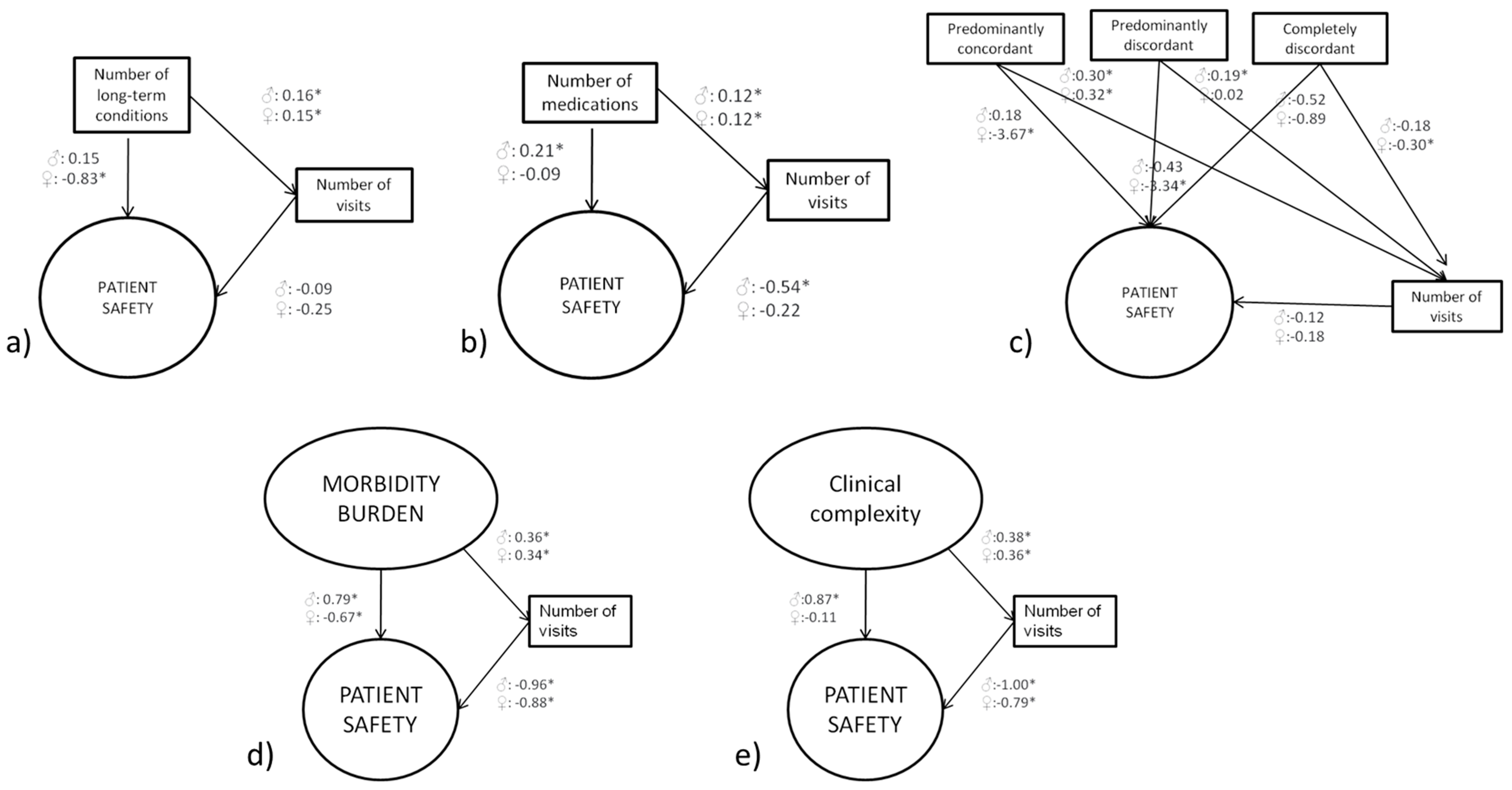

3.3.1. Multimorbidity

3.3.2. Polypharmacy

3.3.3. Comorbidity Discordance

3.3.4. Morbidity Burden

3.3.5. Patient Complexity

3.3.6. Comparison across Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Main Findings and Comparison with the Previous Literature

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications for Research, Practice, Policy

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Description of the Latent Variables

| Morbidity burden | Pairwise Correlations | Confirmatory Factor Analysis Loadings (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Number of conditions | 0.99 * | 0.99 * | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.97) | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) |

| Discordance of conditions | 0.92 * | 0.89 * | 0.89 (0.88 to 0.90) | 0.88 (0.86 to 0.89) |

| Number of medications | 0.66 * | 0.68 * | 0.64 (0.62 to 0.66) | 0.67 (0.64 to 0.70) |

| Age | 0.58 * | 0.59 * | 0.57 (0.54 to 0.60) | 0.58 (0.55 to 0.62) |

| Self-reported health status a | 0.47 * | 0.38 * | 0.46 (0.43 to 0.49) | 0.38 (0.34 to 0.42) |

| Patient Complexity | Pairwise Correlations | Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Loadings (95% CI)) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Number of conditions | 0.98 * | 0.99 * | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.96) | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.98) |

| Concordance of the conditions | 0.92 * | 0.90 * | 0.90 (0.89 to 0.90) | 0.88 (0.87 to 0.89) |

| Number of medications | 0.67 * | 0.69 * | 0.65 (0.63 to 0.67) | 0.67 (0.65 to 0.70) |

| Age | 0.59 * | 0.60 * | 0.58 (0.55 to 0.60) | 0.59 (0.56 to 0.63) |

| Self-reported health status a | 0.47 * | 0.39 * | 0.47 (0.44 to 0.50) | 0.38 (0.34 to 0.42) |

| Educational attainment b | −0.38 * | −0.24 * | 0.38 (0.33 to 0.40) | 0.23 (0.18 to 0.28) |

| Occupational status c | 0.26 * | 0.33 * | 0.25 (0.22 to 0.29) | 0.33 (0.28 to 0.37) |

| Country of origin d | −0.12 * | −0.14 * | 0.12 (0.08 to 0.16) | 0.14 (0.09 to 0.18) |

| Patient Safety | Pairwise Correlations | Confirmatory Factor Analysis Loadings (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Team activation | 0.60 * | 0.55 * | 0.52 (0.48 to 0.55) | 0.46 (0.41 to 0.51) |

| Experiences of safety events | 0.93 * | 0.90 * | 0.79 (0.76 to 0.84) | 0.75 (0.70 to 0.81) |

| Harm-severity | 0.56 * | 0.59 * | 0.48 (0.44 to 0.52) | 0.50 (0.45 to 0.54) |

| Harm-needs | 0.55 * | 0.57 * | 0.47 (0.43 to 0.51) | 0.48 (0.43 to 0.53) |

| Overall rating of patient safety | 0.65 * | 0.67 * | 0.56 (0.52 to 0.60) | 0.56 (0.51 to 0.61) |

References

- Cresswell, K.M.; Panesar, S.S.; Salvilla, S.A.; Carson-Stevens, A.; Larizgoitia, I.; Donaldson, L.J.; Bates, D.; Sheikh, A.; Aibar, C.; Al-Bulushi, H.; et al. Global Research Priorities to Better Understand the Burden of Iatrogenic Harm in Primary Care: An International Delphi Exercise. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, C. The Essentials of Patient Safety; Imperial College of Science, Technology & Medicine: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 9781405192217. [Google Scholar]

- Panesar, S.S.; Desilva, D.; Carson-Stevens, A.; Cresswell, K.M.; Salvilla, S.A.; Slight, S.P.; Javad, S.; Netuveli, G.; Larizgoitia, I.; Donaldson, L.J.; et al. How safe is primary care? A systematic review. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, A.J.; Sheehan, C.; Bell, B.; Armstrong, S.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Boyd, M.J.; Chuter, A.; Cooper, A.; Donnelly, A.; Edwards, A.; et al. Incidence, nature and causes of avoidable significant harm in primary care in England: Retrospective case note review. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2020. Nov 10; Online Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wet, C.; Bowie, P. Patient safety and general practice: Traversing the tightrope. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2014, 64, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ricci-Cabello, I.; Saletti-Cuesta, L.; Slight, S.P.; Valderas, J.M. Identifying patient-centred recommendations for improving patient safety in General Practices in England: A qualitative content analysis of free-text responses using the Patient Reported Experiences and Outcomes of Safety in Primary Care (PREOS-PC) questi. Heal. Expect. 2017, 20, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.J.; Orozco-beltrán, D.; Pérez-jover, V.; Martínez-jimeno, L.; Gil-guillén, V.F.; Carratala-munuera, C.; Sánchez-molla, M.; Pertusa-martínez, S.; Asencio-aznar, A. Physician patient communication failure facilitates medication errors in older polymedicated patients with multiple comorbidities. Fam. Pract. 2013, 30, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slight, S.P.; Howard, R.; Ghaleb, M.; Barber, N.; Franklin, B.D.; Avery, A.J. The causes of prescribing errors in English general practices: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e713–e720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderas, J.M.; Starfield, B.; Sibbald, B.; Salisbury, C.; Roland, M. Defining comorbidity: Implications for understanding health and health services. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009, 7, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violan, C.; Foguet-Boreu, Q.; Flores-Mateo, G.; Salisbury, C.; Blom, J.; Freitag, M.; Glynn, L.; Muth, C.; Valderas, J.M. Prevalence, determinants and patterns of multimorbidity in primary care: A systematic review of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, C.; Johnson, L.; Purdy, S.; Valderas, J.M.; Montgomery, A.A. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2011, 61, e12–e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, K.; Mercer, S.W.; Norbury, M.; Watt, G.; Wyke, S.; Guthrie, B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012, 380, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderas, J.M. Multimorbidity, not a health condition or complexity by another name. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 21, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderas, J.M.; Gangannagaripalli, J.; Nolte, E.; Boyd, C.M.; Roland, M.; Sarria-Santamera, A.; Jones, E.; Rijken, M. Quality of care assessment for people with multimorbidity. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 285, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damarell, R.A.; Morgan, D.D.; Tieman, J.J. General practitioner strategies for managing patients with multimorbidity: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, C.; Blom, J.W.; Smith, S.M.; Johnell, K.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, A.I.; Nguyen, T.S.; Brueckle, M.S.; Cesari, M.; Tinetti, M.E.; Valderas, J.M. Evidence supporting the best clinical management of patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy: A systematic guideline review and expert consensus. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 285, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci-Cabello, I.; Violán, C.; Foguet-Boreu, Q.; Mounce, L.T.A.; Valderas, J.M. Impact of multi-morbidity on quality of healthcare and its implications for health policy, research and clinical practice. A scoping review. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 21, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagioti, M.; Stokes, J.; Esmail, A.; Coventry, P.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S.; Alam, R.; Bower, P. Multimorbidity and patient safety incidents in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, J. Polypharmacy: A necessary evil. BMJ 2013, 347, f7033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnjidic, D.; Hilmer, S.N.; Blyth, F.M.; Naganathan, V.; Waite, L.; Seibel, M.J.; McLachlan, A.J.; Cumming, R.G.; Handelsman, D.J.; Le Couteur, D.G. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: Five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L.C.; Wenger, N.S.; Fung, C.; Chang, J.T.; Ganz, D.A.; Higashi, T.; Kamberg, C.J.; MacLean, C.H.; Roth, C.P.; Solomon, D.H.; et al. Multimorbidity is associated with better quality of care among vulnerable elders. Med. Care 2007, 45, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci-Cabello, I.; Stevens, S.; Kontopantelis, E.; Dalton, A.R.H.; Griffiths, R.I.; Campbell, J.L.; Doran, T.; Valderas, J.M. Impact of the prevalence of concordant and discordant conditions on the quality of diabetes care in family practices in England. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piette, J.D.; Kerr, E.A. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlamangla, A.; Tinetti, M.; Guralnik, J.; Studenski, S.; Wetle, T.; Reuben, D. Comorbidity in older adults: Nosology of impairment, diseases, and conditions. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 62, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safford, M.M.; Allison, J.J.; Kiefe, C.I. Patient complexity: More than comorbidity. The vector model of complexity. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderas, J.M.; Mercer, S.W.; Fortin, M. Research on Patients with Multiple Health Conditions: Different Constructs, Different Views, One Voice. J. Comorbidity 2011, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Ripoll, J.; Llobera, J.; Valderas, J.M.; Pastor-Moreno, G.; Olry De Labry Lima, A.; Ricci-Cabello, I. Development and evaluation of an intervention based on the provision of patient feedback to improve patient safety in Spanish primary healthcare centres: Study protocol. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, A.L.; Johnson, R.; Purdy, S.; Valderas, J.M.; Salisbury, C. Measures of multimorbidity and morbidity burden for use in primary care and community settings: A systematic review and guide. Ann. Fam. Med. 2012, 10, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayliss, E.A.; Ellis, J.L.; Steiner, J.F. Seniors’ self-reported multimorbidity captured biopsychosocial factors not incorporated into two other data-based morbidity measures. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, B.; Vollenweider, P.; Waeber, G.; Marques-Vidal, P. Prevalence of measured and reported multimorbidity in a representative sample of the Swiss population Disease epidemiology—Chronic. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violán, C.; Foguet-Boreu, Q.; Hermosilla-Pérez, E.; Valderas, J.M.; Bolíbar, B.; Fàbregas-Escurriola, M.; Brugulat-Guiteras, P.; Muñoz-Pérez, M.Á. Comparison of the information provided by electronic health records data and a population health survey to estimate prevalence of selected health conditions and multimorbidity. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricci-Cabello, I.; Avery, A.J.; Reeves, D.; Kadam, U.T.; Valderas, J.M. Measuring patient safety in primary care: The development and validation of the “Patient Reported Experiences and Outcomes of Safety in Primary Care” (PREOS-PC). Ann. Fam. Med. 2016, 14, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Ripoll, M.J.; Llobera, J.; Valderas, J.M.; de Labry Lima, A.O.; Fiol-deRoque, M.A.; Ripoll, J.; Ricci-Cabello, I. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validation and Piloting of the Patient Reported Experiences and Outcomes of Safety in Primary Care (PREOS-PC) Questionnaire for Its Use in Spain. J. Patient Saf. 2021. Volume Publish Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounce, L.T.A.; Salema, N.; Gangannagaripalli, J.; Ricci-Cabello, I.; Avery, A.J.; Kadam, U.T.; Valderas, J.M. Development of two short patient-report questionnaires of patient safety in Primary Care. J. Patient Saf. 2021. Volume Publish Ahead of Print. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; Willey: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. PriPrinciples and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. Nciples and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues and Applications; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y. Handbook of Latent Variable and Related Models; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 9780444520449. [Google Scholar]

- Kupek, E. Beyond logistic regression: Structural equations modelling for binary variables and its application to investigating unobserved confounders. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2006, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberto, C.K.; Pintor, J.K.; Langellier, B.; Tabb, L.P.; Martínez-Donate, A.P.; Stimpson, J.P. Association of maternal characteristics with latino youth health insurance disparities in the United States: A generalized structural equation modeling approach. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aho, K.; Derryberry, D.; Peterson, T. Model selection for ecologists: The worldviews of AIC and BIC. Ecology 2014, 95, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci-Cabello, I.; Reeves, D.; Bell, B.G.; Valderas, J.M. Identifying patient and practice characteristics associated with patient-reported experiences of safety problems and harm: A cross-sectional study using a multilevel modelling approach. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijken, M.; Valderas, J.M.; Heins, M.; Schellevis, F.; Korevaar, J. Identifying high-need patients with multimorbidity from their illness perceptions and personal resources to manage their health and care: A longitudinal study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounce, L.T.A.; Campbell, J.L.; Henley, W.E.; Tejerina Arreal, M.C.; Porter, I.; Valderas, J.M. Predicting incident multimorbidity. Ann. Fam. Med. 2018, 16, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruneir, A.; Bronskill, S.E.; Maxwell, C.J.; Bai, Y.Q.; Kone, A.J.; Thavorn, K. The association between multimorbidity and hospitalization is modified by individual demographics and physician continuity of care: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderas, J.M.; Starfield, B.; Roland, M. A research priority in the UK. BMJ 2007, 334, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderas, J.M. Increasing Clinical, Community, and Patient-Centered Health Research for Preventing and Managing Multimorbidity. J. Comorbidity 2013, 3, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Women

(n = 3059; 64%) | Men

(n = 1723; 36%) | Total

(n = 4782) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 51.12 (18) | 54.06 (19) | 52.1 (19) |

| <18 | 56 (2%) | 60 (3%) | 116 (2%) |

| 18–29 | 346 (11%) | 160 (9%) | 506 (11%) |

| 30–44 | 747 (24%) | 315 (18%) | 1062 (22%) |

| 45–64 | 1097 (36%) | 581 (34%) | 1678 (35%) |

| ≥65 | 811 (27%) | 607 (35%) | 1418 (30%) |

| Educational level | |||

| University studies | 597 (19%) | 244 (14%) | 835 (16%) |

| Other qualifications | 1744 (57%) | 1075 (62%) | 2816 (59%) |

| No qualifications | 724 (24%) | 404 (23%) | 1128 (24%) |

| Country of origin | |||

| Spain | 2618 (86%) | 1546 (90%) | 4164 (87%) |

| Other country (European Union) | 122 (4%) | 56 (3%) | 178 (4%) |

| Other country (Non-European Union) | 319 (10%) | 121 (7%) | 440 (9%) |

| Occupational status | |||

| Working | 1532 (50%) | 804 (47%) | 2336 (49%) |

| Unemployed | 342 (11%) | 87 (5%) | 429 (9%) |

| Retired | 862 (28%) | 710 (41%) | 1572 (33%) |

| Other (student, volunteering, etc.) | 323 (11%) | 122 (7%) | 445 (9%) |

| Visits to PHC centre in the previous 12 months | |||

| 1–5 | 1672 (55%) | 993 (58%) | 2665 (56%) |

| 6–10 | 767 (25%) | 388 (23%) | 1155 (24%) |

| 11–20 | 395 (13%) | 230 (13%) | 625 (13%) |

| >20 | 225 (7%) | 112 (7%) | 337 (7%) |

| Health status | |||

| Very good | 366 (12%) | 237 (14%) | 603 (13%) |

| Good | 1420 (46%) | 891 (52%) | 2311 (48%) |

| Fair | 999 (33%) | 472 (27%) | 1471 (31%) |

| Bad | 208 (7%) | 96 (6%) | 304 (6%) |

| Very bad | 66 (2%) | 27 (2%) | 93 (2%) |

| Number of long-term conditions | |||

| Mean (SD; range) | 2.20 (2.17; 0–16) | 2.13 (1.95; 0–10) | 2.17 (2.09; 0–16) |

| 0 | 816 (27%) | 441 (26%) | 1257 (26%) |

| 1 | 628 (21%) | 331 (19%) | 959 (20%) |

| 2 to 3 | 865 (28%) | 638 (37%) | 1433 (30%) |

| >3 | 750 (25%) | 383 (22%) | 1131 (24%) |

| Long-term conditions | |||

| Hypertension | 815 (27%) | 611 (35%) | 1426 (30%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 684 (22%) | 510 (30%) | 1195 (25%) |

| Diabetes | 309 (10%) | 333 (19%) | 642 (13%) |

| Asthma or bronchitis or emphysema | 322 (11%) | 178 (10%) | 500 (10%) |

| Long-term heart problem | 250 (8%) | 284 (16%) | 534 (11%) |

| Stomach ulcer | 134 (4%) | 58 (3%) | 192 (4%) |

| Allergy | 597 (20%) | 244 (14%) | 841 (18%) |

| Depression | 523 (17%) | 151 (9%) | 674 (14%) |

| Other mental health problems | 187 (6%) | 91 (5%) | 278 (6%) |

| Migraine/headaches | 578 (19%) | 107 (6%) | 685 (14%) |

| Blood circulation problems | 587 (19%) | 219 (13%) | 806 (17%) |

| Hernia | 274 (9%) | 220 (13%) | 494 (10%) |

| Arthrosis and rheumatic problems | 921 (30%) | 349 (20%) | 1270 (27%) |

| Osteoporosis | 305 (10%) | 25 (1%) | 330 (7%) |

| Menstruation-related problems | 232 (8%) | - | 232 (5%) |

| Prostate-related problems | - | 287 (17%) | 287 (6%) |

| Number of medications | |||

| Mean (SD; range) | 2.25 (2.94; 0–30) | 2.61 (3.15; 0–27) | 2.38 (3.02; 0–30) |

| 0 | 1129 (38%) | 560 (33%) | 1689 (36%) |

| 1 | 472 (16%) | 253 (15%) | 725 (16%) |

| 2–4 | 1038 (35%) | 607 (36%) | 1645 (35%) |

| 5–10 | 282 (9%) | 216 (13%) | 498 (11%) |

| >10 | 67 (2%) | 40 (2%) | 107 (2%) |

| Women | Men | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Score | Score Range (Min–Max) | Mean (SD) Score | Score Range (Min–Max) | Mean (SD) Score | Score Range (Min–Max) | |

| Patient activation | 38.13 (36.93) | 6.25–100 | 39.99 (37.85) | 0–100 | 38.80 (37.27) | 0–100 |

| Team activation | 79.81 (20.22) | 6.25–100 | 84.01 (18.32) | 18.75–100 | 81.32 (19.66) | 6.25–100 |

| Experiences of safety events | 91.81 (13.33) | 0–100 | 93.51 (12.25) | 0–100 | 92.42 (12.98) | 0–100 |

| Harm (severity) | 96.43 (11.86) | 0–100 | 96.83 (11.75) | 0–100 | 96.58 (11.81) | 0–100 |

| Harm (needs) | 95.98 (12.61) | 0–100 | 96.97 (10.99) | 0–100 | 96.34 (12.06) | 0–100 |

| Overall rating of patient safety | 83.51 (16.50) | 0–100 | 84.82 (15.55) | 0–100 | 83.98 (16.18) | 0–100 |

| Women (β (95% CI)) | Men (β (95% CI)) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Pathway | Direct Pathway | AIC | Indirect Pathway | Direct Pathway | AIC | |||

| MM to Visits | Visits to PS | MM to PS | MM to Visits | Visits to PS | MM to PS | |||

| Number of conditions ⱡ | 0.15 (0.13 to 0.16) * | −0.25 (−0.24 to 0.74) | −0.83 (−1.08 to −0.57) * | 129,086.9 | 0.16 (0.14 to 0.18) * | −0.09 (−0.65 to 0.47) | 0.15 (−0.17 to 0.48) | 71,554.63 |

| Number of medications ⱡ | 0.12 (0.10 to 0.13) * | −0.22 (−0.73 to 0.29) | −0.09 (−0.28 to 0.10) | 126,845.7 | 0.12 (0.11 to 0.14) * | −0.54 (−1.08 to −0.01) * | 0.21 (0.03 to 0.39) * | 69,863.42 |

| Comorbidity discordance ⱡ | 69,106.07 | 39,370.94 | ||||||

| Completely concordant (ref.) | - | −0.18 (−0.46 to 0.82) | - | - | −0.12 (−0.69 to 0.46) | - | ||

| Predominantly concordant | 0.32 (0.10 to 0.54) * | −3.67 (−6.44 to −0.90) * | 0.30 (0.09 to 0.52) * | 0.18 (−1.78 to 2.15) | ||||

| Predominantly discordant | 0.02 (−0.15 to 0.20) | −3.34 (−5.53 to −1.16) * | 0.19 (0.03 to 0.35) * | −0.43 (−1.88 to 1.03) | ||||

| Completely discordant | −0.30 (−0.49 to −0.12) * | −0.89 (−3.27 to 1.49) | −0.18 (−0.36 to −0.01) * | −0.52 (−2.20 to 1.16) | ||||

| Morbidity burden ¶ | 0.34 (0.30 to 0.37) * | −0.88 (−1.36 to −0.40) * | −0.67 (−1.17 to −0.18) * | 191,973 | 0.36 (0.31 to 0.41) * | −0.96 (−1.42 to −0.51) * | 0.79 (0.32 to 1.26) * | 107,340 |

| Patient Complexity † | 0.36 (0.32 to 0.40) * | −0.79 (−1.27 to −0.31) * | −0.11 (−0.61 to 0.39) | 211,882.2 | 0.38 (0.33 to 0.43) * | −1.00 (−1.46 to −0.53) * | 0.87 (0.38 to 1.36) * | 117,935 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ricci-Cabello, I.; Yañez-Juan, A.M.; Fiol-deRoque, M.A.; Leiva, A.; Llobera Canaves, J.; Parmentier, F.B.R.; Valderas, J.M. Assessing the Impact of Multi-Morbidity and Related Constructs on Patient Reported Safety in Primary Care: Generalized Structural Equation Modelling of Observational Data. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10081782

Ricci-Cabello I, Yañez-Juan AM, Fiol-deRoque MA, Leiva A, Llobera Canaves J, Parmentier FBR, Valderas JM. Assessing the Impact of Multi-Morbidity and Related Constructs on Patient Reported Safety in Primary Care: Generalized Structural Equation Modelling of Observational Data. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(8):1782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10081782

Chicago/Turabian StyleRicci-Cabello, Ignacio, Aina María Yañez-Juan, Maria A. Fiol-deRoque, Alfonso Leiva, Joan Llobera Canaves, Fabrice B. R. Parmentier, and Jose M. Valderas. 2021. "Assessing the Impact of Multi-Morbidity and Related Constructs on Patient Reported Safety in Primary Care: Generalized Structural Equation Modelling of Observational Data" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 8: 1782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10081782

APA StyleRicci-Cabello, I., Yañez-Juan, A. M., Fiol-deRoque, M. A., Leiva, A., Llobera Canaves, J., Parmentier, F. B. R., & Valderas, J. M. (2021). Assessing the Impact of Multi-Morbidity and Related Constructs on Patient Reported Safety in Primary Care: Generalized Structural Equation Modelling of Observational Data. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(8), 1782. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10081782