Abstract

Background: Abdominal aortic aneurysm represents a distinct group of vascular lesions, in terms of surveillance and treatment. Screening and follow-up of patients via duplex ultrasound has been well established and proposed by current guidelines. However, serum circulating biomarkers could earn a position in individualized patient surveillance, especially in cases of aggressive AAA growth rates. A systematic review was conducted to assess the correlation of AAA expansion rates with serum circulating biomarkers. Methods: A data search of English medical literature was conducted, using PubMed, EMBASE, and CENTRAL, until 7 March 2021, in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement (PRISMA) guidelines. Studies reporting on humans, on abdominal aortic aneurysm growth rates and on serum circulating biomarkers were included. No statistical analysis was conducted. Results: A total of 25 studies with 4753 patients were included. Studies were divided in two broad categories: Those reporting on clinically applicable (8 studies) and those reporting on experimental (17 studies) biomarkers. Twenty-three out of 25 studies used duplex ultrasound (DUS) for following patients. Amongst clinically applicable biomarkers, D-dimers, LDL-C, HDL-C, TC, ApoB, and HbA1c were found to bear the most significant association with AAA growth rates. In terms of the experimental biomarkers, PIIINP, osteopontin, tPA, osteopontin, haptoglobin polymorphisms, insulin-like growth factor I, thioredoxin, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and genetic factors, as polymorphisms and microRNAs were positively correlated with increased AAA expansion rates. Conclusion: In the presence of future robust data, specific serum biomarkers could potentially form the basis of an individualized surveillance strategy of patients presenting with increased AAA growth rates.

1. Introduction

Despite abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) being an asymptomatic entity, rupture complicates this silent pathology with a high mortality risk. Aneurysm identification on incidental imaging or screening programs at an early stage and small diameter allows for a close surveillance and repair [1]. However, not all aneurysms expand with the same rate and are not associated with the same risk of rupture, while diameter cannot always predict the physical evolution of an AAA [2,3,4]. A plethora of studies using imaging modalities and AAA anatomical characteristics tended to define models that could describe the expansion model of small or larger AAAs [5,6,7,8]. From ultrasonography to modern mathematical flow models, different methods have been used to identify these markers that could eliminate this group of patients needing closer re-evaluation and earlier management [9].

As different anatomical characteristics recorded on imaging modalities have been associated with aneurysm expansion, an analogous interest exists regarding the application of biomarkers that could identify AAA growth [10,11]. However, important discrepancies exist among the available studies [11]. A large spectrum of biomarkers is recorded in the current literature, from the commonly applied clinical circulating biomarkers to more specific sophisticated genetic models that could be used to evaluate AAA expansion rate [12]. The need to predict aneurysm evolution and if possible, to hamper sac expansion, is of high interest, as this approach would permit a closer surveillance screening and a more individualized therapeutic approach.

Along this line, a systematic review was conducted to present the existing evidence of different circulating biomarkers that may have a potential role on AAA growth prediction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligible Studies

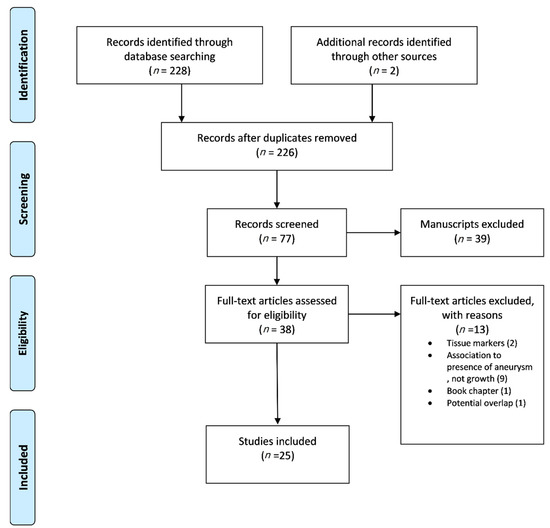

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed [13]. Studies of English medical literature, reporting data on the evaluation of biomarkers (see Section 2.5), regarding their potential role on the identification of AAA growth (see Section 2.5) on humans, were considered eligible. Studies referring to data based on animal studies, any other aortic pathology besides AAA, and non-plasma circulating biomarkers (unavailable by venipuncture) were excluded. Scientific council approval in terms of ethical considerations was not required due to the nature of the study. Data extraction and methodological assessment was carried out by two independent investigators (P.N., K.D.). Any discrepancy was resolved after consultation by a senior investigator (G.K.). Consequently, a full-text review of the eligible studies was conducted, respecting the eligibility and exclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow chart of the selection process according to PRISMA statement.

2.2. Search Strategy

A data search of English medical literature was conducted, the endpoint being 7 March 2021. The established medical databases PubMed, EMBASE, and CENTRAL were searched under the patient/population, intervention, comparison and outcomes (PICO) model, in order to determine the clinical questions and select the appropriate articles (Supplementary Table S1) [14]. The following search terms including Expanded Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used in various combinations: Abdominal aortic aneurysm, growth, biomarker. Primary selection was constructed on titles and abstracts, while a secondary investigation was executed based on full texts.

2.3. Data Extraction

A standard Microsoft Excel extraction file was developed. Extracted data included general data such as article author, year of publication, study period, journal of publication, and type of study. In addition, clinical data extracted from text or tables included the number of patients included, cohort characteristics, biomarker in evaluation, method of biomarker assessment, growth rate definition in each study, type of imaging used, correlation of biomarker to AAA growth, and statistical significance.

2.4. Quality Assessment

Quality assessment for individual studies and risk of bias evaluation was addressed using the ROBINS-I tool [15] for observational, non-randomized studies and the RoB-II tool [16] for randomized, controlled studies. Observational studies were judged as bearing a “Low”, “Moderate”, “Serious”, or “Critical” risk of bias, based on 7 domains, while RCTs were evaluated bearing a “Low”, “Some concerns”, or a “High” risk of bias, based on 5 domains (Supplementary Table S2). Risk of bias evaluation was carried out by two independent investigators (P.N., K.D.). In cases of disagreement, a third author was advised (G.K.).

2.5. Definitions

A biomarker was considered a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention, as defined by the biomarkers.

2.6. Definitions Working Group

AAA growth was considered as the difference among two measurements of the maximal anteroposterior diameter of a diagnosed abdominal aortic aneurysm, based on measurements achieved either by ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), between two set timepoints, at least 12 months apart or more. AAA growth was measured as mm/year [17].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Only descriptive data were presented, because this systematic review did not aim to compare the efficacy of biomarkers on AAA growth.

3. Results

Twenty-five studies with 4753 patients were included in this systematic review. To facilitate data presentation, the studies were divided into two groups. The first group included studies assessing clinically applicable biomarkers and the second group included studies recording data on experimental biomarkers not used in the daily clinical practice.

Eight studies presenting data on clinical biomarkers were included; one randomized control trial [18], 3 prospective [19,20,21], and 4 retrospective [22,23,24,25] observational studies, published between 2008 and 2018 (Table 1). All analyses assessed patients that underwent screening controls or were hospital referrals and presented an AAA of more than 30 mm of diameter (range 30–50 mm). Considering experimental circulating biomarkers, 17 articles were included, all presenting results from prospective [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] observational studies, except one retrospective [42] analysis (Table 2). In total, 3152 patients with AAA of more than 30 mm were included (range 30–49 mm).

Table 1.

General characteristics of studies on circulating clinical biomarkers.

Table 2.

General characteristics of studies on circulating experimental biomarkers.

Among studies presenting clinical biomarkers, the most commonly applied one was D-dimers which was assessed in three studies [20,21,25]. D-dimers’ role as an indicator of the process of thrombosis and thrombolysis and their known association with other cardiovascular entities has been assessed to further identify their potential impact on AAA evolution. The lipidemic biomarkers (total cholesterol [18], apolipoprotein-B [18], low density lipids (LDL) [18] and high-density lipids (HDL) [22]) and C-reactive protein (CRP) [19] have been used due to their proven role on the process of atherothrombosis and their relationship to a higher-risk of cardiovascular events. In one study, the role of HbA1 c was addressed due to the already known negative association between diabetes and AAA pathogenesis [24]. All the markers assessed in the studies, as well as the potential underlying etiopathologic relationship between them and AAA evolution is presented in Table 3. In the experimental group, a variety of biomarkers was applied to identify prediction models in AAA evolution (Table 4). Nine out of them participate in the inflammation cascade while 3 are associated with the physiological coagulation mechanisms and 2 on the degenerative procedures of the tissues. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin was studied as an indicator of the inflammatory degenerative process of aneurysm formation [34,42] and evolution while the potential role of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and II was analyzed under the spectrum of the negative association between diabetes and AAA [33]. The etiopathological association of all experimental markers and AAA growth is also presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Specific characteristics of studies on circulating clinical biomarkers.

Table 4.

Specific characteristics of studies on circulating experimental biomarkers.

For the evaluation of aneurysm growth, duplex ultrasonography (DUS) was used in the vast majority of the studies (23 out of 25 studies) [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,42]. Aneurysm growth definition varied among studies. The change in the antero-posterior diameter of the aneurysm sac during the whole observation period divided by the aforementioned time interval (diameter at the latest evaluation-diameter at the initial evaluation/time interval in years) was used in 15 studies to identify the annual growth rate of the aneurysm. All approaches used to evaluate AAA growth rate are presented in Table 3 and Table 4.

D-dimers were positively associated in 3 studies with aneurysm growth with an associated statistical significance. In accordance, the lipidemic markers played a predictive role in AAA expansion; total cholesterol and apolipoprotein-B had a positive relation while HDL presented a negative association; higher HDL levels were associated with lower AAA growth. The negative association of diabetes and AAA pathogenesis was detected by the negative correlation between HbA1 and expansion rate. The association between clinical biomarkers and AAA growth is presented in Table 5. Among the experimental biomarkers, amino-terminal propeptide of type III procollagen (PIIINP) [26], tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) [27,29,40], osteopontin [34], haptoglobin polymorphism [30], IGF I and II [33], thioredoxin (TRX) [31], neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [41], and genetic factors, as polymorphisms [35] and micro RNAs [36] were positively associated with aneurysm expansion. Two studies reported no association between NGAL and AAA growth [34,42]. All data regarding the experimental markers are available in Table 6.

Table 5.

The association between clinical biomarkers and AAA growth. Notes: AAA: Abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Table 6.

The association between experimental biomarkers and AAA growth.

Risk of Bias Evaluation

Twenty-four observational studies were assessed on 7 domains (ROBINS-I tool), while 1 RCT was assessed on 5 domains (RoB-II tool). Twenty-one [19,20,21,22,23,25,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] out of 24 observational studies were attributed a “Moderate” risk of bias, while the rest 3 [24,26,42] were attributed a “Serious” risk of bias (Supplementary Table S2). The RCT [18] was attributed a “Some Concerns” risk of bias grade. Confounders on which the studies were judged included consistency and control of method of biomarker evaluation, potential subgroup analysis of patients, method of imaging technique, and number and experience of imaging techniques operators.

4. Discussion

AAA represent a category of vascular lesions with high morbidity and mortality, especially in the case of aneurysm rupture. Current guidelines suggest elective repair based mainly on aneurysmal diameter and/or other characteristics of the AAA [8,43]. Proposed screening strategies vastly stand on imaging techniques, including mainly DUS, adhering to the phenomenon of increased rupture risk in patients of specific demographic attributes and AAA diameter [44]. Studies have shown that patients with particular aneurysmal attributes would be acceptable surgical candidates, especially for endovascular interventions, even if AAA diameter has not achieved the diameter’s threshold [45,46]. While AAA growth is observed through typical, time-set imaging follow-up, stratification of high-risk patients with expeditious AAA growth, through serum biomarkers, could be a valid approach for individualized imaging surveillance. These patients could benefit from a rather targeted surveillance approach as well as an early endovascular or open surgical repair.

The pathogenesis of AAAs advocates for an extensive list of serum circulating or histologically detected biomarker candidates. Each category bears an important role in the different phases of the natural history of AAA [47,48,49]. Biomarkers detected through histological evaluation of an AAA open surgical repair specimen do not conform with the concept of preoperative surveillance and disease progression and therefore cannot be used in clinical practice. However, serum circulating biomarkers appertaining to recognized pathophysiologic processes of AAA pathogenesis, including thrombosis, inflammation, extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, lipid metabolism, as well as genetic predisposition, could potentially form the basis of a stratification screening or surveillance strategy for patients in need of more frequent follow-up.

As proposed by many studies, certain mediators or by-products of thrombosis and lipid metabolism have been linked to AAA growth. These biomarkers can be easily and cost-effectively implemented in everyday clinical practice [18,19,20,22,25]. D-dimers, a known fibrin degradation by-product, has been shown to be associated with AAA expansion, as higher levels have been correlated with increased growth rate. Correlation of other thrombosis-related biomarkers, including PAP complex [21,50], homocysteine [51], and TAT [25], has also been reported. Higher levels of HDL-C, a biomarker related to lipid metabolism, have been correlated with decreased AAA growth rates in a screening population [22]. Furthermore, increased levels of total cholesterol and apolipoprotein B, both markers easily quantified and major constituents of lipid metabolism, have been associated with increased growth rates of AAA [18]. On the other hand, given the potentially protective nature of diabetes mellitus in AAA, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) has been studied as a possible biomarker of inverse association with AAA expansion [52,53,54,55]. A lower growth rate was observed in patients with higher HbA1c levels; 1.8 mm/year decrease of rate in HbA1c 44–77 compared to 28–39 mmol/mol [24]. The recognized correlations of the abovementioned biomarkers, in addition to their cost-effectiveness and their wide-spread use in everyday clinical practice, renders them attractive candidates for future studies aiming to provide robust data on their relation to AAA expansion rates.

Concurrently, a plethora of less utilized biomarkers correlating to various stages of AAA progression have been studied, posturing as alluring secondary candidates. Firstly, extracellular matrix components and degradation enzymes have been associated with AAA growth rate. The well-defined role of elastin, biglycan, and type III collagen in the structural integrity of the aortic wall provided the basis for studies reporting data on the by-products of these proteins associated with ΑΑΑ progress and increased sac expansion [18,26,29,56,57]. Inadvertently, extracellular matrix proteinases (MMP-2, MMP-9 [58], cathepsins B, D, L, and S [59]) responsible for ECM cleavage, and proteinases inhibitors (a1-antithrypsin [19], cystatin-B [37], cystatin-C [60]) play a significant role in the aortic wall remodeling occurring in AAA pathogenesis with several studies revealing either positive or inverse correlations with AAA growth rates. An abundance of modulators and mediators expressing the inflammatory and oxidative processes have also been studied with conflicting outcomes [31,32,38,61,62]. Synchronously, studies on promising novel biomarkers requiring genome sequencing analysis have been conducted, with propitious results. Specifically, genomic DNA analysis of genetic polymorphisms showed increased risk of aggressive-growth over slow-growth AAA [36,41,63,64,65]. Current data on these aforementioned biomarkers are promising, despite the fact that firm conclusions cannot be provided. Interestingly, calprotectin, a protein commonly associated with inflammatory cells (neutrophil granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages), has been related to AAA pathogenesis. These results provide further solid ground for future trials, aiming to assess the relation between the antimicrobial protein and AAA growth rate [66,67]. As the knowledge on AAA pathogenesis increases, novel studies may offer validated markers that could be used for the detection of this high-risk group of patients while pharmaceutical factors may provide a conservative management on AAA presence and expansion.

Limitations

The strength of the current review is limited by a series of factors. Firstly, the retrospective nature of the included studies confines its ability to reach pertinent results. Secondly, vast incoherencies among studies in terms of the types of biomarker assessed, studied population and cohorts, lack of control groups, follow-up intervals, and standardized methodological evaluations (imaging techniques, biomarkers quantification methods) impede the production of robust results, as well as the ability of quantitative analysis of the said results. Finally, most studies were judged as having “Moderate” risk of bias, mainly due to selection bias and inadequate confounder control.

5. Conclusions

Blood circulating biomarkers may offer a valid approach in the future for the detection of AAA expansion. The current literature provides a plethora of data with conflicting results and firm conclusions cannot be provided. In the presence of future robust data, specific serum biomarkers could potentially form the basis of an individualized surveillance strategy of patients presenting with increased AAA growth rates.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm10081718/s1, Table S1: PICO model, Table S2: Risk of Bias Assessment (ROBINS-I) for Observational Studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S., G.K.; methodology, P.N., K.D., A.B.; software, A.B.; validation, P.N., A.B.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, P.N., K.S., K.D.; data curation, P.N., K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N., K.D.; writing—review and editing, P.N., K.D., K.S., G.K.; visualization, G.K.; supervision, G.K.; project administration, K.S., G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Golledge, J. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: Update on pathogenesis and medical treatments. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 16, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurvers, H.; Veith, F.; Lipsitz, E.; Ohki, T.; Gargiulo, N.; Cayne, N.; Suggs, W.; Timaran, C.; Kwon, G.; Rhee, S. Discontinuous, staccato growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2004, 199, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.L.; Wijesinha, M.A.; Panthofer, A.M.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Upchurch, G.R.; Terrin, M.L.; Curci, J.A.; Baxter, B.T.; Matsumura, J.S. Evaluating Growth Patterns of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Diameter With Serial Computed Tomography Surveillance. JAMA Surg. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spanos, K.; Eckstein, H.-H.; Giannoukas, A.D. Small Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Are Not All the Same. Angiology 2019, 71, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, R.O.; Newby, D.E.; Robson, J.M.J. Monitoring the biological activity of abdominal aortic aneurysms beyond Ultrasound. Heart 2016, 102, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalzadeh, H.; Indrakusuma, R.; Planken, R.N.; Legemate, D.A.; Koelemay, M.J.W.; Balm, R. Inflammation as a Predictor of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth and Rupture: A Systematic Review of Imaging Biomarkers. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2016, 56, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, K.; Nana, P.; Kouvelos, G.; Mpatzalexis, K.; Matsagkas, M.; Giannoukas, A.D. Anatomical Differences Between Intact and Ruptured Large Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2020, 27, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanhainen, A.; Verzini, F.; Van Herzeele, I.; Allaire, E.; Bown, M.; Cohnert, T.; Dick, F.; Van Herwaarden, J.; Karkos, C.; Koelemay, M.; et al. Editor’s Choice—European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2019 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2019, 57, 8–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, R.O.; Newby, D.E. Imaging Biomarkers for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms: Finding the Breakthrough. Vol. 12, Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2019. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30871335/ (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Torres-Fonseca, M.; Galan, M.; Martinez-Lopez, D.; Cañes, L.; Roldan-Montero, R.; Alonso, J.; Rodríguez, C.; Sirvent, M.; Miguel, L.; Martínez, R.; et al. Pathophisiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm: Biomarkers and novel therapeutic targets. Clin. Investig. Arterioscler. 2019, 31, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wanhainen, A.; Mani, K.; Golledge, J. Surrogate Markers of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Progression. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Ghoorah, K.; Kunadian, V. Abdominal aortic aneurysms and risk factors for adverse events. Cardiol. Rev. 2016, 24, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.A.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, C. Subject and Course Guides: Evidence Based Medicine: PICO. Available online: https://researchguides.uic.edu/c.php?g=252338&p=3954402 (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.J.; Colburn, W.A.; DeGruttola, V.G.; DeMets, D.L.; Downing, G.J.; Hoth, D.F.; Oates, J.A.; Peck, C.C.; Schooley, R.; Spilker, B.; et al. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: Preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Deeg, M.A.; Meijer, C.A.; Chan, L.S.; Shen, L.; Lindeman, J.H.N. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers of abdominal aortic aneurysm growth rate. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2016, 32, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega de Céniga, M.; Esteban, M.; Quintana, J.M.; Barba, A.; Estallo, L.; de la Fuente, N.; Martin-Ventura, J.L. Search for Serum Biomarkers Associated with Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth—A Pilot Study. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2009, 37, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golledge, J.; Muller, R.; Clancy, P.; McCann, M.; Norman, P.E. Evaluation of the diagnostic and prognostic value of plasma D-dimer for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. Hear. J. 2010, 32, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Ceniga, M.V.; Esteban, M.; Barba, A.; Estallo, L.; Blanco-Colio, L.M.; Martin-Ventura, J.L. Assessment of Biomarkers and Predictive Model for Short-term Prospective Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth—A Pilot Study. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 28, 1642–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burillo, E.; Lindholt, J.S.; Molina-Sánchez, P.; Jorge, I.; Martinez-Pinna, R.; Blanco-Colio, L.M. ApoA-I/HDL-C levels are inversely associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm progression. Thromb. Haemost. 2015, 113, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Moxon, J.V.; Jones, R.E.; Norman, P.E.; Clancy, P.; Flicker, L.; Almeida, O.P.; Hankey, G.J.; Yeap, B.B.; Golledge, J. Plasma ferritin concentrations are not associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm diagnosis, size or growth. Atherosclerosis 2016, 251, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, K.L.; Dahl, M.; Rasmussen, L.M.; Lindholt, J.S. Glycated hemoglobin is associated with the growth rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms a substudy from the VIVA (Viborg vascular) randomized screening trial. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundermann, A.C.; Saum, K.; Conrad, K.A.; Russell, H.M.; Edwards, T.L.; Mani, K.; Björck, M.; Wanhainen, A.; Owens, A.P. Prognostic value of D-dimer and markers of coagulation for stratification of abdominal aortic aneurysm growth. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 3088–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satta, J.; Haukipuro, K.; Kairaluoma, M.I.; Juvonen, T. Aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen in the follow-up of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 1997, 25, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholt, J.; Jørgensen, B.; Shi, G.-P.; Henneberg, E. Relationships between activators and inhibitors of plasminogen, and the progression of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2003, 25, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Golledge, J.; Muller, J.; Shephard, N.; Clancy, P.; Smallwood, L.; Moran, C.; Dear, A.E.; Palmer, L.J.; Norman, P.E. Association Between Osteopontin and Human Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flondell-Sité, D.; Lindblad, B.; Kölbel, T.; Gottsäter, A. Markers of Proteolysis, Fibrinolysis, and Coagulation in Relation to Size and Growth Rate of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2010, 44, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiernicki, I.; Safranow, K.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Piatek, J.; Gutowski, P. Haptoglobin 2-1 phenotype predicts rapid growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 52, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Pinna, R.; Lindholt, J.; Blanco-Colio, L.; Dejouvencel, T.; Madrigal-Matute, J.; Ramos-Mozo, P.; de Ceniga, M.V.; Michel, J.; Egido, J.; Meilhac, O.; et al. Increased levels of thioredoxin in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). A potential link of oxidative stress with AAA evolution. Atherosclerosis 2010, 212, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Ventura, J.; Lindholt, J.; Moreno, J.; de Céniga, M.V.; Meilhac, O.; Michel, J.; Egido, J.; Blanco-Colio, L. Soluble TWEAK plasma levels predict expansion of human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Atherosclerosis 2011, 214, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholt, J.S.; Martin-Ventura, J.L.; Urbonavicius, S.; Ramos-Mozo, P.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Egido, J.; Frystyk, J. Insulin-like growth factor i—A novel biomarker of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 42, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Mozo, P.; Madrigal-Matute, J.; de Ceniga, M.V.; Blanco-Colio, L.M.; Meilhac, O.; Feldman, L.; Michel, J.-B.; Clancy, P.; Golledge, J.; Norman, P.E.; et al. Increased plasma levels of NGAL, a marker of neutrophil activation, in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis 2012, 220, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Austin, E.; Schaid, D.J.; Kullo, I.J. A multi-locus genetic risk score for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis 2016, 246, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanhainen, A.; Mani, K.; Vorkapic, E.; De Basso, R.; Björck, M.; Länne, T.; Wågsäter, D. Screening of circulating microRNA biomarkers for prevalence of abdominal aortic aneurysm and aneurysm growth. Atherosclerosis 2017, 256, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.L.; Lindholt, J.S.; Shi, G.P.; Zhang, J. Plasma Cystatin B Association With Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms and Need for Later Surgical Repair: A Sub-study of the VIVA Trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 56, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Kuravi, S.; Hodson, J.; Rainger, G.E.; Nash, G.B.; Vohra, R.K.; Bradbury, A.W. The Relationship Between Serum Interleukin-1α and Asymptomatic Infrarenal Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Size, Morphology, and Growth Rates. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2018, 56, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindholt, J.S.; Madsen, M.; Kirketerp-Møller, K.L.; Schlosser, A.; Kristensen, K.L.; Andersen, C.B.; Sorensen, G.L. High plasma microfibrillar-associated protein 4 is associated with reduced surgical repair in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 71, 1921–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memon, A.; Zarrouk, M.; Ågren-Witteschus, S.; Sundquist, J.; Gottsäter, A.; Sundquist, K. Identification of novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilenberg, W.; Zagrapan, B.; Bleichert, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Knöbl, V.; Brandau, A.; Martelanz, L.; Grasl, M.-T.; Hayden, H.; Nawrozi, P.; et al. Histone citrullination as a novel biomarker and target to inhibit progression of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Transl. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, M.E.; Struik, J.A.; Musters, R.J.; Tangelder, G.J.; Koolwijk, P.; Niessen, H.W.; Hoksbergen, A.W.; Wisselink, W.; Yeung, K.K. The Potential Role of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in the Development of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 57, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikof, E.L.; Dalman, R.L.; Eskandari, M.K.; Jackson, B.M.; Lee, W.A.; Mansour, M.A.; Mastracci, T.M.; Mell, M.; Murad, M.H.; Nguyen, L.L.; et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 67, 2–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederle, F.A.; Kane, R.L.; MacDonald, R.; Wilt, T.J. Systematic review: Repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 146, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; De Rango, P.; Verzini, F.; Parlani, G.; Romano, L.; Cieri, E. Comparison of Surveillance Versus Aortic Endografting for Small Aneurysm Repair (CAESAR): Results from a Randomised Trial. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 41, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouriel, K. The PIVOTAL study: A randomized comparison of endovascular repair versus surveillance in patients with smaller abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 49, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golledge, J.; Tsao, P.S.; Dalman, R.L.; Norman, P.E. Circulating Markers of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Presence and Progression. Circulation 2008, 118, 2382–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagi, H.; Nishigori, M.; Murakami, Y.; Osaki, T.; Muto, S.; Iba, Y.; Minatoya, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Ishibashi-Ueda, H.; Morisaki, T.; et al. Discovery of novel biomarkers for atherosclerotic aortic aneurysm through proteomics-based assessment of disease progression. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenthal, F.A.M.V.I.; Buurman, W.A.; Wodzig, W.K.W.H.; Schurink, G.W.H. Biomarkers of abdominal aortic aneurysm progression. Part 2: Inflammation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2009, 6, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholt, J.S.; Jørgensen, B.; Fasting, H.; Henneberg, E.W. Plasma levels of plasmin-antiplasmin-complexes are predictive for small abdominal aortic aneurysms expanding to operation-recommendable sizes. J. Vasc. Surg. 2001, 34, 611–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Halazun, K.J.; Bofkin, K.A.; Asthana, S.; Evans, C.; Henderson, M.; Spark, J.I. Hyperhomocysteinaemia is Associated with the Rate of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Expansion. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2007, 33, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rango, P.; Farchioni, L.; Fiorucci, B.; Lenti, M. Diabetes and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2014, 47, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theivacumar, N.S.; Stephenson, M.A.; Mistry, H.; Valenti, D. Diabetes mellitus and aortic aneurysm rupture: A favorable association? Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2014, 48, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dattani, N.; Sayers, R.D.; Bown, M.J. Diabetes mellitus and abdominal aortic aneurysms: A review of the mechanisms underlying the negative relationship. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2018, 15, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederle, F.A.; Johnson, G.R.; Wilson, S.E.; Chute, E.P.; Littooy, F.N.; Bandyk, D.F.; Krupski, W.C.; Barone, G.W.; Acher, C.W.; Ballard, D.J. Prevalence and Associations of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Detected through Screening. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 126, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrin, P.B. Elastin, collagen, and some mechanical aspects of arterial aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 1989, 9, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, A.D.; Karamanos, N.K. Decreased biglycan expression and differential decorin localization in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Atherosclerosis 2002, 165, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Aikawa, M. Many faces of matrix metalloproteinases in aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 752–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaus, V.; Schmies, F.; Reeps, C.; Trenner, M.; Geisbüsch, S.; Lohoefer, F.; Eckstein, H.-H.; Pelisek, J. Cathepsin S is associated with degradation of collagen I in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Vasa 2018, 47, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholt, J.S.; Erlandsen, E.J.; Henneberg, E.W. Cystatin C deficiency is associated with the progression of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. BJS 2001, 88, 1472–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jana, S.; Hu, M.; Shen, M.; Kassiri, Z. Extracellular matrix, regional heterogeneity of the aorta, and aortic aneurysm. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, E.; Clément, M.; Lareyre, F.; Sweeting, M.; Raffort, J.; Grenier, C.; Finigan, A.; Harrison, J.; Peters, J.E.; Sun, B.B.; et al. Interleukin-6 Receptor Signaling and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Growth Rates. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2019, 12, e002413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duellman, T.; Warren, C.L.; Matsumura, J.; Yang, J. Analysis of multiple genetic polymorphisms in aggressive-growing and slow-growing abdominal aortic aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 60, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Shang, T.; Huang, C.; Yu, T.; Liu, C.; Qiao, T.; Huang, D.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C. Plasma microRNAs serve as potential biomarkers for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 48, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kin, K.; Miyagawa, S.; Fukushima, S.; Shirakawa, Y.; Torikai, K.; Shimamura, K.; Sawa, Y. Tissue- and plasma-specific MicroRNA signatures for atherosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysm. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012, 1, e000745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauzer, W.; Witkiewicz, W.; Gnus, J. Calprotectin and Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products as a Potential Biomarker in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauzer, W.; Ferenc, S.; Rosińczuk, J.; Gnus, J. The Role of Serum Calprotectin as a New Marker in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms—A Preliminary Report. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).