Cardiac Arrhythmias in Survivors of Sudden Cardiac Death Requiring Impella Assist Device Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics and Outcome

3.2. Incidence of Arrhythmias during Assist Device Therapy

3.3. Arrhythmias in Survivors vs. in Hospital Death

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zipes, D.P.; Wellens, H.J. Sudden cardiac death. Circulation 1998, 98, 2334–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Heart Rhythm Association; Heart Rhythm Society; Zipes, D.P. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force and the European society of cardiology committee for practice guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, e247–e346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lackermair, K.; Sattler, S.; Huber, B.C. Retrospective analysis of circulatory support with the Impella CP(R) device in patients with therapy refractory cardiogenic shock. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 219, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaire, A.; Anderson, M.B.; Lee, L.Y. The Impella device for acute mechanical circulatory support in patients in cardiogenic shock. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014, 97, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhruva, S.S.; Ross, J.S.; Mortazavi, B.J. Association of use of an intravascular microaxial left ventricular assist device vs intra-aortic balloon pump with in-hospital mortality and major bleeding among patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. JAMA 2020, 323, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abaunza, M.; Kabbani, L.S.; Nypaver, T. Incidence and prognosis of vascular complications after percutaneous placement of left ventricular assist device. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 62, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boriani, G.; Fauchier, L.; Aguinaga, L. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document on management of arrhythmias and cardiac electronic devices in the critically ill and post-surgery patient, endorsed by Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), Cardiac Arrhythmia Society of Southern Africa (CASSA), and Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS). Europace 2019, 21, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kalarus, Z.; Svendsen, J.H.; Capodanno, D. Cardiac arrhythmias in the emergency settings of acute coronary syndrome and revascularization: An European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) consensus document, endorsed by the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), and European Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA). Europace 2019, 21, 1603–1604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Le Pennec-Prigent, S.; Flecher, E.; Auffret, V. Effectiveness of extracorporeal life support for patients with cardiogenic shock due to intractable arrhythmic storm. Crit. Care. Med. 2017, 45, e281–e289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaki, A.; Subahi, A.; Shokr, M. Impella-Induced incessant ventricular tachycardia. Ochsner J. 2019, 19, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaver, C.M.; Chen, W.; Janz, D.R. Atrial Fibrillation is an independent predictor of mortality in critically ill patients. Crit. Care. Med. 2015, 43, 2104–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonu, G.; Rupak, D.; Bishoy, H. The impact of atrial fibrillation on in-hospital outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock undergoing coronary revascularization with percutaneous ventricular assist device support. J. Atr. Fibrillation 2020, 12, 2179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martinell, L.; Nielsen, N.; Herlitz, J. Early predictors of poor outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit. Care. 2017, 21, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n | Median (Q3–Q1) or % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 30 | 27.5% |

| Age | 109 | 69.0 (18.0) |

| Impella 2.5 L | 84 | 77.1% |

| Impella 3.5 L | 25 | 22.9% |

| LVEF (%) | 85 | 20.0 (20.00) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 87 | 79.8% |

| Acute PCI | 67 | 61.5% |

| Duration of CPR (minutes) | 105 | 20.00 (25.00) |

| Initial rhythm during CPR | ||

| VT/VF | 80 | 73.4% |

| Asystole | 18 | 16.5% |

| PEA | 11 | 10.1% |

| General medical history | ||

| Arterial hypertension | 62 | 56.9% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 | 23.9% |

| Hyperlipidemia | 42 | 38.5% |

| CAD | 96 | 88.1% |

| PAD | 9 | 8.3% |

| HFrEF | 45 | 41.3% |

| HFpEF | 7 | 6.4% |

| Valvular heart disease | 10 | 9.2% |

| Structural heart disease | 26 | 23.9% |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 4 | 3.7% |

| COPD | 10 | 9.2% |

| Malignancy | 10 | 9.2% |

| Medical history of arrhythmias | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 21 | 19.3% |

| Other SVT | 6 | 5.5% |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 27 | 24.8% |

| Laboratory | ||

| creatinine (mg/dL) | 107 | 1.50 (0.70) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 107 | 13.00 (3.00) |

| Leucocytes (x/µL) | 106 | 14,490 (10,365) |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 105 | 320.00 (988.00) |

| GOT (U/L) | 104 | 135.00 (229.25) |

| Lactate (U/L) | 93 | 6.0 (6.35) |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 98 | 4.20 (0.90) |

| Outcomes | n = 109 | Median (Q3–Q1) or % |

|---|---|---|

| General outcome | ||

| Duration of Impella therapy (days) | 104 | 1.00 (2.00) |

| ICU stay (days) | 109 | 2.00 (4.50) |

| Total hospital stay (days) | 109 | 3 (6.00) |

| Apoplex | 4 | 3.7% |

| Total in hospital death | 91 | 83.5% |

| Cause of death | ||

| Low output failure | 66 | 60.6% |

| Septic shock | 15 | 13.8% |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 2 | 1.8% |

| Incessant VT | 4 | 3.7% |

| Brain death | 2 | 1.8% |

| Abdominal ischemia or compartment | 2 | 1.8% |

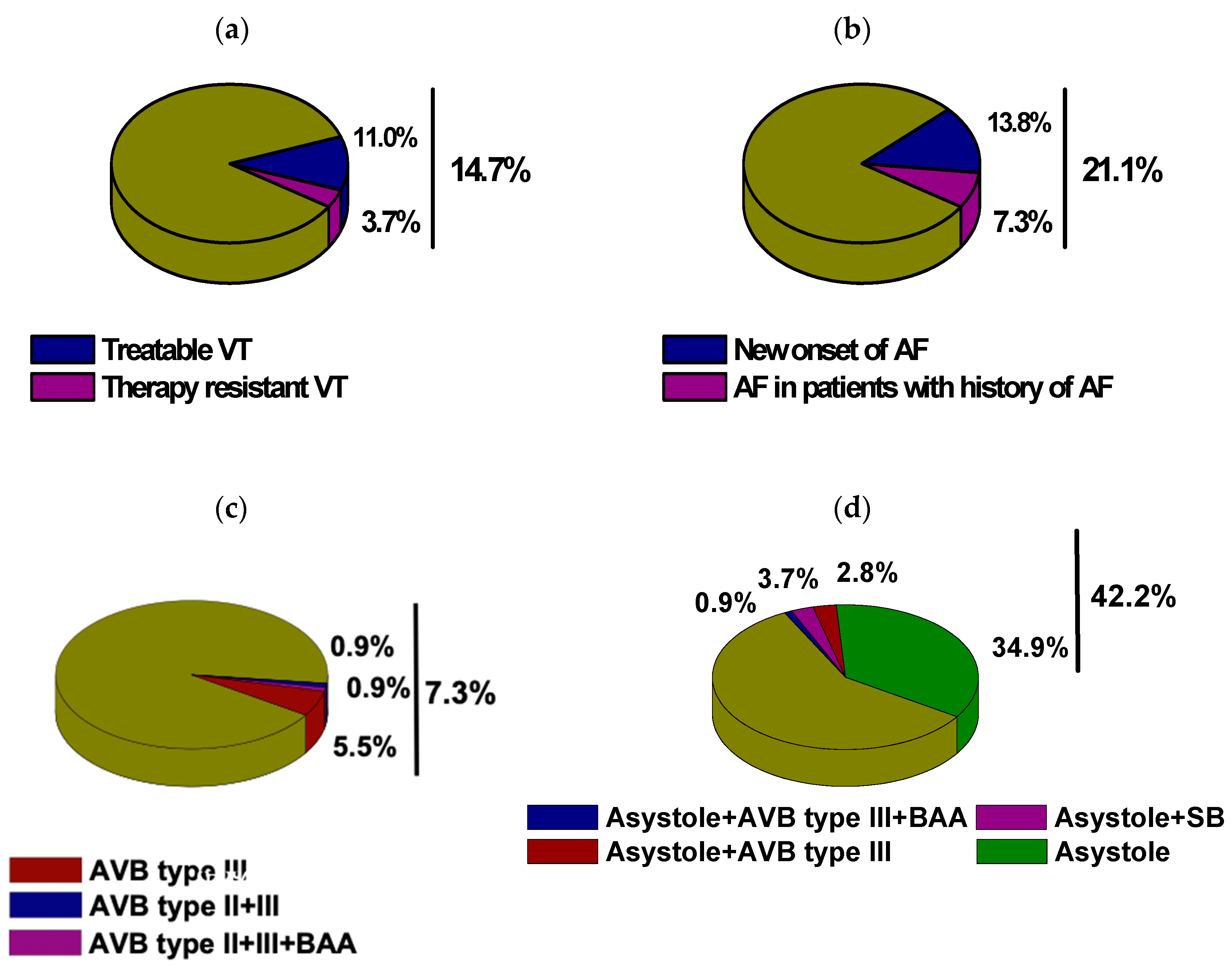

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 25 | 22.9% |

| AF | 23 | 21.1% |

| New-onset AF | 15 | 13.8% |

| Other SVT | 4 | 3.7% |

| Ventricular Tachycardia | 20 | 18.3% |

| Non-sustained VT | 5 | 4.6% |

| Sustained VT | 16 | 14.7% |

| Therapy-resistant VT | 4 | 3.7% |

| Bradycardia | 50 | 45.9% |

| Sinus bradycardia | 5 | 4.6% |

| Bradyarrhythmia absoluta | 2 | 1.8% |

| Higher degree AVB | 8 | 7.3% |

| Asystole | 46 | 42.2% |

| In Hospital Death (n = 91) | In Hospital Survival (n = 18) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Initial rhythm during CPR | |||||

| VT/VF | 64 | 70.3% | 16 | 88.9% | 0.103 |

| Asystole | 17 | 18.7% | 1 | 5.6% | 0.171 |

| PEA | 10 | 11.0% | 1 | 5.6% | 0.484 |

| Arrhythmia burden during Impella therapy | |||||

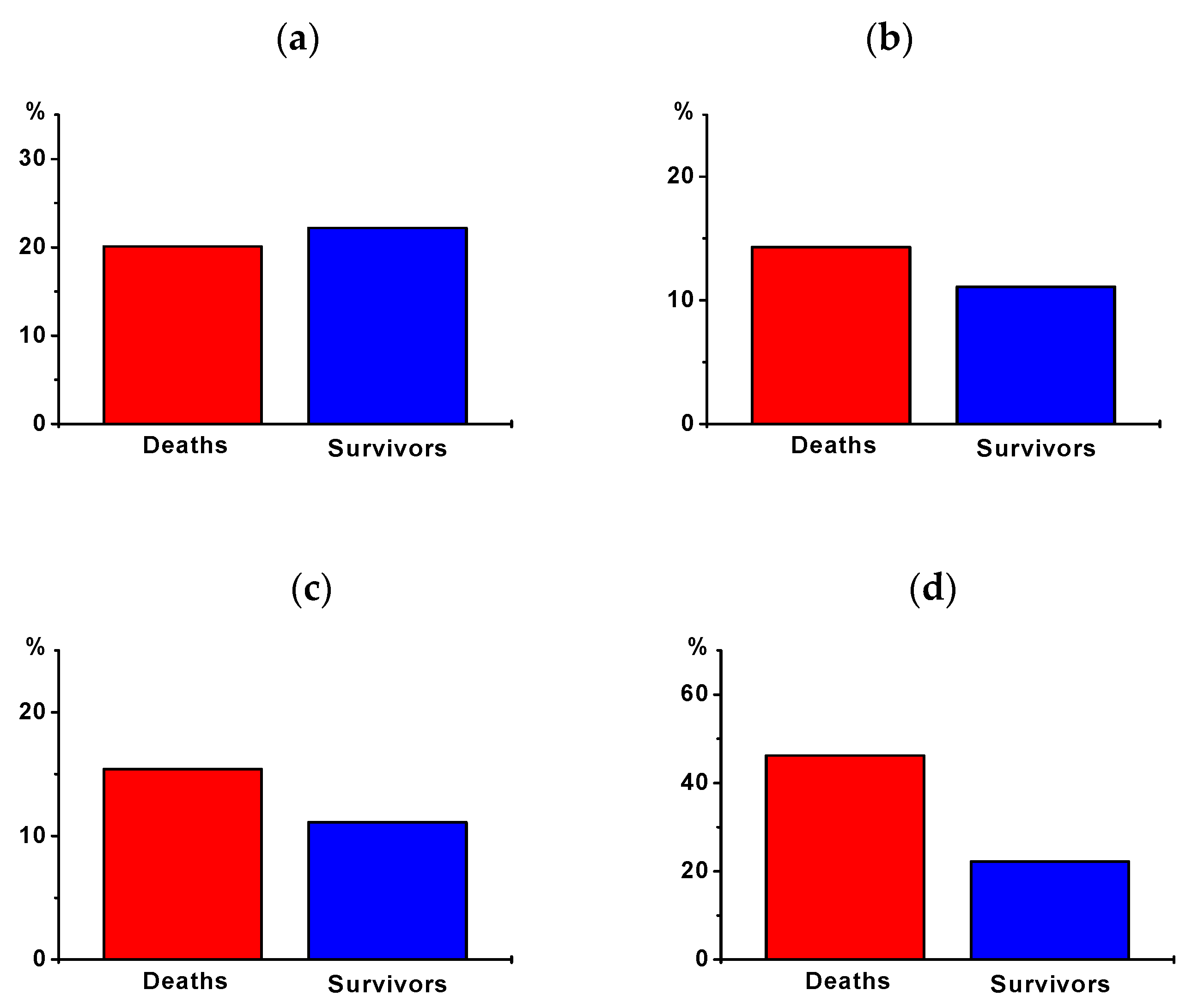

| Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias | |||||

| AF | 19 | 20.1% | 4 | 22.2% | 0.898 |

| New-onset AF | 13 | 14.3% | 2 | 11.1% | 0.721 |

| Other SVT | 3 | 3.3% | 1 | 5.6% | 0.641 |

| Ventricular tachyarrhythmias | |||||

| Non-sustained VT | 3 | 3.3% | 2 | 11.1% | 0.148 |

| Sustained VT | 14 | 15.4% | 2 | 11.1% | 0.640 |

| Therapy-resistant VT | 4 | 4.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.365 |

| Bradyarrhythmias | |||||

| Sinus bradycardia | 3 | 3.3% | 2 | 11.1% | 0.148 |

| Bradyarrhythmia absoluta | 2 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.526 |

| Higher degree AVB | 7 | 7.7% | 1 | 5.6% | 0.751 |

| Asystole | 42 | 46.2% | 4 | 22.2% | 0.060 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdullah, K.Q.A.; Roedler, J.V.; vom Dahl, J.; Szendey, I.; Dimitroulis, D.; Eckardt, L.; Topf, A.; Ohnewein, B.; Fritsch, L.; Föttinger, F.; et al. Cardiac Arrhythmias in Survivors of Sudden Cardiac Death Requiring Impella Assist Device Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10071393

Abdullah KQA, Roedler JV, vom Dahl J, Szendey I, Dimitroulis D, Eckardt L, Topf A, Ohnewein B, Fritsch L, Föttinger F, et al. Cardiac Arrhythmias in Survivors of Sudden Cardiac Death Requiring Impella Assist Device Therapy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(7):1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10071393

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Khaled Q. A., Jana V. Roedler, Juergen vom Dahl, Istvan Szendey, Dimitrios Dimitroulis, Lars Eckardt, Albert Topf, Bernhard Ohnewein, Lorenz Fritsch, Fabian Föttinger, and et al. 2021. "Cardiac Arrhythmias in Survivors of Sudden Cardiac Death Requiring Impella Assist Device Therapy" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 7: 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10071393

APA StyleAbdullah, K. Q. A., Roedler, J. V., vom Dahl, J., Szendey, I., Dimitroulis, D., Eckardt, L., Topf, A., Ohnewein, B., Fritsch, L., Föttinger, F., Brandt, M. C., Wernly, B., Motloch, L. J., & Larbig, R. (2021). Cardiac Arrhythmias in Survivors of Sudden Cardiac Death Requiring Impella Assist Device Therapy. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(7), 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10071393