Patient and Therapist Perspectives on Treatment for Adults with PTSD from Childhood Trauma

Abstract

1. Introduction:

Patient and Therapist Perspectives on Treatment for Adults with PTSD from Childhood Trauma

2. Method

2.1. Study Context and Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Semi-Structured Interview

2.4. Research Assistants

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

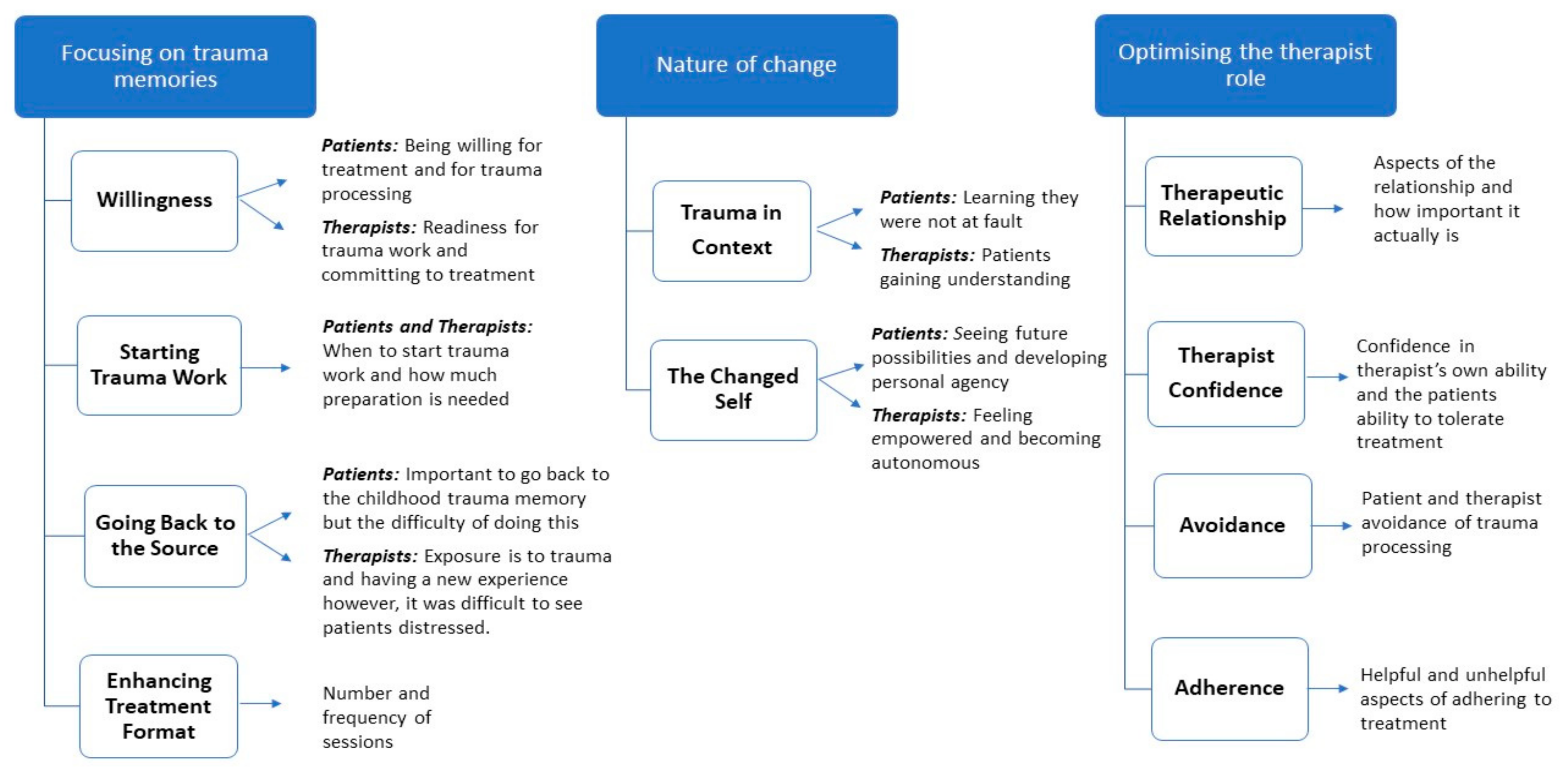

3. Results

3.1. Focusing on Trauma Memories

3.1.1. Willingness

Participant 19: “Of course the willpower that you really want to change something. That is the most important. If there is no willpower, it won’t work. If I want to change something and work on such a trauma, then I really have to want it.”

Participant 9: “I think this treatment would work the vast majority of cases, but… everybody is different... I got out of it, because I gave a lot into it. I came here when I didn’t want to, and would still jump in … and still get involved, as how hard it was.”

Therapist 16: “Well, certainly the motivation... the readiness, you know, to do trauma work. It’s helpful, you know, just in terms of people’s ability to come and commit and to tolerate the work.”

3.1.2. Starting Trauma Work

Therapist 11: “I think in a lot of cases, it’s best to start as soon as possible with trauma-focused therapy. But I guess in some cases, it’s better to first build some skills and use the phase-based therapy. Then people are able to cope with the possible effects of the trauma therapy.”

Participant 23: “I knew what I was starting. Of course you never know how it’s going to work. But you know what it’s for and what exactly is going to happen. I thought the explanation, the information you get… I don’t think more is necessary because then you’re going to think about everything.”

Participant 30: “You know, in my case, if it (the introduction) were (any) longer… then I would get scared or confused. I would’ve said I don’t want to do it anymore.”

Therapist 2: “I’m now having had this experience of the research I’m quite surprised that we could go in there and do stuff so quickly and have good results without poor outcomes with actually good outcomes and now and then occasional situations there were risks that—were actually managed.”

3.1.3. Going Back to the Source

Participant 27: “I don’t know how you would treat it otherwise. It is just something that had a big impact on your life. Something that you weren’t able to deal with correctly. So the only way to fix that is to go back and do it over, I think.”

Therapist 15: “What (is) helpful is that... they go into the trauma again and have a new experience in their brains and then they start to think in a different way. They don’t feel guilt anymore because it’s not a secret anymore.”

Participant 10: “It was difficult but I feel that it needed to be done that way... I think, it was kind of like kind of a slap in the face but a good one. So, what I am trying to say is, yes, it was hard going back like that … but I think that was partly necessary.”

Therapist 5: “Not to fear your emotions and you have to be able to stand for minutes, and minutes, and minutes and see that somebody is not going well, not at all and to accept that, you do not have to do the changes. It’s not your job to change things, it’s the patient’s job to try.”

3.1.4. Enhancing Treatment Format

Participant 8: “I think if there was a two or four more to just see me through, just to help me just get through the last few doors you know, because I still struggle with things.”

Therapist 4: “I often have the feeling in the 12 sessions they need so much more.”

Therapist 13: “I’m not sure. I thought it was okay. With the patient I treated, it was really okay. We almost didn’t know what to address at the end. We almost had sessions open. With the other patient, … She was in process but it was just she needed more.”

Participant 31: “I didn’t experience anything negative about it. It’s hard, twice a week, but not uhm… it’s very effective, a lot has happened.”

Therapist 7: “I think it’s good. I think it’s good because yeah, it is, everything is so fresh in the patient’s memory. You can easily come back to what you have done in the session before … And I think it’s good for patients to have a short intense of treatment. I think it’s more effective than just feeling it really. To me it feels more effective than 12 sessions and 12 weeks. Yeah, but at the same time I found it pretty intense for me too and its very time consuming.”

Therapist 15: “Sometimes it’s too busy for us but I think it’s very good that they come twice a week but there are sometimes for whom it would be better to come once a week I think. That are clients who have emotionally not that much control and they need few days’ rest.”

3.2. Nature of Change

3.2.1. Trauma in Context

Therapist 9: “Well, I do think that they very often recognise what they missed and it’s however painful … So instead of thinking, they were the dirty child or the guilty child, they see that they were a child in very bad circumstances and that of course when you face that and you really feel something about it then afterwards you get more mild towards yourself.”

Participant 21: “How I look at myself in those situations has definitely changed… I can now honestly say that I did what I could as a child... there was nothing I should have done to begin with, so I didn’t fail to do anything. Or neglect to do anything. That I’m less hard on myself, in that sense. I am less critical of myself.”

Participant 16: “I do think differently about myself. I don’t see myself as this monster, Frankenstein, this massively damaged and broken thing. I still see the injuries I sustained but now I know they can heal, at least to a certain degree, and they can even have positive effects. I would surely not be the artist I am today without those experiences... I did see it before therapy but now I believe it.”

Participant 11: “I think after the treatment I felt more empowered and like even though I couldn’t do anything I could do something now to help myself. So, it really made me feel like in control of what happened, if that makes sense, in a weird way.”

3.2.2. The Changed Self

Participant 23: “Let’s just say, it wasn’t in my nature. The possibility of a future … I didn’t see any possibilities. Because there weren’t any possibilities. And now I think differently. The possibilities are different.”

Therapist 5: “They find a lot that they are able to look at that they are strong enough... are able to experience the feelings, able to experience the ideas and the pictures and the thoughts and... their role changes and they’re not a victim anymore.”

Participant 25: “I am stronger, I think more clearly, I’m not afraid anymore … I can enjoy things more, I have a less internal battles … almost none, and if there is one then I can handle it well.”

Participant 19: “I don’t put up with everything … I just say: ‘hey, I’m a human being as well with feelings and I’m valuable’ and I don’t have to be there for others all the time... A lot of times I said ‘the most important thing is that the others feel fine, I don’t matter’ but now...’ I won’t do that. I don’t want to do that.”

3.3. Optimising the Therapist Role

3.3.1. Therapeutic Relationship

Therapist 10: “It’s the working alliance... there’s enough safety in the structure and the rules. It’s clear what’s going to happen, that the patient has control or is in control.”

Therapist 15: “If you have good contact and… they trust you, … people will change because in time they trust themselves and feel comfortable… then they can change by themselves, I don’t change.”

Therapist 4: “I think the relationship between patient and therapist is important. I also think it’s sometimes overrated. It’s important but it’s not for every patient that important but a lot of therapists think it is. Just my opinion.”

3.3.2. Therapist Confidence

Therapist 14: “I think that it’s important that the therapist is not afraid and can give patients a feeling of confidence… like a doctor,... it’s important that the doctor gives you the idea that he knows what he or she knows what he does and that it’s ok and that he is in control.”

Therapist 3: “Don’t be afraid to kind of push your client… I think there is a lot of possibility going on and look I think,... if you give the client that option, they can do it.”

3.3.3. Avoidance

Therapist 11: “I think that is one of the most important part that they are not running away from it and not putting it away in their mind.”

Therapist 13: “What I really felt in our centre is that therapists are very reluctant to do trauma-focused therapy with these patients that they feel that you need to protect them... They’re afraid to de-stabilise this patient.”

3.3.4. Adherence

Therapist 16: “The really good thing about it is that it was really structured and it forced us to get going much sooner than we normally would. You had to do processing in every session which has been great because I know that outside of it I get far too easily side tracked and we are distracted by crisis and stuff and avoid it.”

Therapist 10: “That we are used to calm down the client or do some relaxation exercise, but the protocol says, well, you should go on… We are used to taking care… (patients) can take time out. But afterward, I see well, it was right… Just to keep going.”

Therapist 5: “Well you have to stick to the protocol, but you are not allowed to use them (strategies), what I feel that there’s something missing and I cannot do it, that’s unhelpful for me.”

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cloitre, M.; Courtois, C.A.; Charuvastra, A.; Carapezza, R.; Stolbach, B.C.; Green, B.L. Treatment of complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. J. Trauma. Stress 2011, 24, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatzias, T.; Murphy, P.; Cloitre, M.; Bisson, J.; Roberts, N.; Shevlin, M.; Hyland, P.; Maercker, A.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Coventry, P.; et al. Psychological interventions for ICD-11 complex PTSD symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohus, M.; Dyer, A.S.; Priebe, K.; Krüger, A.; Kleindienst, N.; Schmahl, C.; Niedtfeld, I.; Steil, R. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder after Childhood Sexual Abuse in Patients with and without Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Psychother. Psychosom. 2013, 82, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzias, T.; Cloitre, M. Treating Adults with Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Using a Modular Approach to Treatment: Rationale, Evidence, and Directions for Future Research. J. Trauma. Stress 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jongh, A.; Resick, P.A.; Zoellner, L.A.; van Minnen, A.; Lee, C.W.; Monson, C.M.; Foa, E.B.; Wheeler, K.; Broeke, E.T.; Feeny, N.; et al. Critical analysis of the current treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foa, E.B.; Gillihan, S.J.; Bryant, R.A. Challenges and successes in dissemination of evidence-based treatments for posttraumatic stress: Lessons learned from prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2013, 14, 65–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Minnen, A.; Hendriks, L.; Olff, M. When do trauma experts choose exposure therapy for PTSD patients? A controlled study of therapist and patient factors. Behav. Res. Ther. 2010, 48, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouliara, Z.; Karatzias, T.; Gullone, A. Recovering from childhood sexual abuse: A theoretical framework for practice and research. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 21, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, C.; Murray, C. Adult service-users’ experiences of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2014, 44, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Minnen, A.; Harned, M.S.; Zoellner, L.; Mills, K. Examining potential contraindications for prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloitre, M.; Courtois, C.; Ford, J.; Green, B.; Alexander, P.; Briere, J.; Herman, J.; Lanius, R.; Stolbach, B.; Spinazzola, J. The ISTSS Expert Consensus Treatment Guidelines for Complex PTSD in Adults; ISTSS: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; Available online: https://istss.org/clinical-resources/treating-trauma/new-istss-prevention-and-treatment-guidelines (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Cook, J.M.; Schnurr, P.P.; Foa, E.B. Bridging the gap between posttraumatic stress disorder research and clinical practice: The example of exposure therapy. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 2004, 41, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simiola, V.; Neilson, E.C.; Thompson, R.; Cook, J.M. Preferences for trauma treatment: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2015, 7, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.B.; Darius, E.; Schaumberg, K. An analog study of patient preferences for exposure versus alternative treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 2861–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frueh, B.C.; Cusack, K.J.; Grubaugh, A.L.; Sauvageot, J.A.; Wells, C. Clinicians’ perspectives on cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006, 57, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzek, J.I.; Eftekhari, A.; Rosen, C.S.; Crowley, J.J.; Kuhn, E.; Foa, E.B.; Hembree, E.A.; Karlin, B.E. Factors related to clinician attitudes toward prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. J. Trauma. Stress 2014, 27, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, C.B.; Zayfert, C.; Anderson, E. A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004, 42, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, F.; Maxfield, L. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Information processing in the treatment of trauma. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arntz, A.; Weertman, A. Treatment of childhood memories: Theory and practice. Behav. Res. Ther. 1999, 37, 715–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntz, A. Imagery rescripting as a therapeutic technique: Review of clinical trials, basic studies, and research agenda. J. Exp. Psychopathol. 2012, 3, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, F. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures, 2nd ed.; Guildford: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L.K.; Skavenski, S.; Michalopoulos, L.M.; Bolton, P.A.; Bass, J.K.; Familiar, I.; Imasiku, M.; Cohen, J. Counselor and client perspectives of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children in Zambia: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014, 43, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirdal, G.M.; Ryding, E.; Essendrop Sondej, M. Traumatized refugees, their therapists, and their interpreters: Three perspectives on psychological treatment. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2012, 85, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouliara, Z.; Karatzias, T.; Scott-Brien, G.; Macdonald, A.; MacArthur, J.; Frazer, N. Talking Therapy Services for Adult Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse (CSA) in Scotland: Perspectives of Service Users and Professionals. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2011, 20, 128–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.; Spitzer, R.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0); Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Harnett Sheehan, K.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; Keskiner, A.; Schinka, J.; Knapp, E.; Sheehan, M.F.; Dunbar, G.C. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur. Psychiatry 1997, 12, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, K.L.B.; Lee, C.W.; Fassbinder, E.; Voncken, M.J.; Meewisse, M.; Van Es, S.M.; Menninga, S.; Kousemaker, M.; Arntz, A. Imagery rescripting and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing for treatment of adults with childhood trauma-related post-traumatic stress disorder: IREM study design. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, K.L.B.; Lee, C.W.; Fassbinder, E.; Rijkeboer, M.; Van Es, S.M.; Menninga, S.; Meewisse, M.L.; Kousemaker, M.; Arntz, A. Imagery rescripting and eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing as treatment for adults with post-traumatic stress disorder from childhood trauma: A randomised clinical trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2020, 217, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2018; VERBI Software: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearing, V.; Lee, D.; Clohessy, S. How do clients experience reliving as part of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder? Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2011, 84, 458–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, K.; Stalker, C.A.; Palmer, S.; Gadbois, S. Adults traumatized by child abuse: What survivors need from community-based mental health professionals. J. Ment. Health 2008, 17, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stige, S.H.; Binder, P.-E.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; TrÆen, B. Stories from the road of recovery—How adult, female survivors of childhood trauma experience ways to positive change. Nord. Psychol. 2013, 65, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harned, M.S.; Schmidt, S.C. Perspectives on a stage-based treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder among dialectical behavior therapy consumers in public mental health settings. Community Ment. Health J. 2019, 55, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoellner, L.A.; Feeny, N.C.; Cochran, B.; Pruitt, L. Treatment choice for PTSD. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouliara, Z.; Karatzias, T.; Gullone, A.; Ferguson, S.; Cosgrove, K.; Burke Draucker, C. Therapeutic Change in Group Therapy for Interpersonal Trauma: A Relational Framework for Research and Clinical Practice. J. Interpers. Violence 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, S.M.; Keasler, A.L.; Reaves, R.C.; Channer, E.G.; Bukowski, L.T. The Story of My Strength: An Exploration of Resilience in the Narratives of Trauma Survivors Early in Recovery. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2007, 14, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, B.J.; Johnson, C.V. Voices of healing and recovery from childhood sexual abuse. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2013, 22, 822–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stige, S.H.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Træen, B. A meaningful struggle: Trauma clients’ experiences with an inclusive stabilization group approach. Psychother. Res. 2013, 23, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Eftekhari, A.; Ruzek, J.I.; Crowley, J.J.; Rosen, C.S.; Greenbaum, M.A.; Karlin, B.E. Effectiveness of National Implementation of Prolonged Exposure Therapy in Veterans Affairs Care. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutner, C.A.; Gallagher, M.W.; Baker, A.S.; Sloan, D.M.; Resick, P.A. Time course of treatment dropout in cognitive–behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2016, 8, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | No. (%) of Patients ᵃ |

|---|---|

| n= 44 | |

| Age, Mean (SD), years | 40 (12.16) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 32 (72.7) |

| Male | 12 (27.3) |

| Country | |

| Australia | 12 (27.3) |

| Germany | 25 (56.8) |

| Netherlands | 7 (15.9) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Partner | 28 (63.6) |

| Education level | |

| High school or less | 13 (29.6) |

| College or above | 31 (70.3) |

| Work status | |

| Working | 19 (43.1) |

| Disability pension | 11 (25.0) |

| Unemployed | 9 (20.5) |

| Other | 5 (11.4) |

| Psychological History | |

| PTSD duration, Mean (SD), months | 237.82 (183.54) |

| Co-morbid mood disorder | 32 (72.7) |

| Co-morbid anxiety disorder | 25 (56.8) |

| Previous Treatment | 34 (77.3) |

| Previous Psychiatric Admission | 21 (47.7) |

| Index Trauma History ᵇ | |

| Sexual Abuse/Assault | 23 (52.3) |

| Physical Abuse | 13 (29.5) |

| Other | 8 (18.1) |

| Index trauma onset, Mean (SD), years | 7.57 (3.78) |

| Index trauma duration, Mean (SD), years | 8.25 (4.50) |

| Characteristics | No. (%) of Therapists ᵃ |

|---|---|

| n = 16 | |

| Age, Mean (SD), y | 42.38 (7.84) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 14 (87.5) |

| Male | 2 (12.5) |

| Country | |

| Australia | 3 (18.8) |

| Germany | 4 (25.0) |

| Netherlands | 9 (56.3) |

| Theoretical Orientation | |

| CBT | 15 (93.8) |

| Schema Therapy | 10 (62.5) |

| EMDR | 7 (43.8) |

| DBT | 5 (31.3) |

| Therapy Experience, Mean (SD), y | |

| Years of practice (overall) | 16 (8.97) |

| Years with Ch-PTSD | 7.13 (6.78) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boterhoven de Haan, K.L.; Lee, C.W.; Correia, H.; Menninga, S.; Fassbinder, E.; Köehne, S.; Arntz, A. Patient and Therapist Perspectives on Treatment for Adults with PTSD from Childhood Trauma. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050954

Boterhoven de Haan KL, Lee CW, Correia H, Menninga S, Fassbinder E, Köehne S, Arntz A. Patient and Therapist Perspectives on Treatment for Adults with PTSD from Childhood Trauma. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(5):954. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050954

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoterhoven de Haan, Katrina L., Christopher W. Lee, Helen Correia, Simone Menninga, Eva Fassbinder, Sandra Köehne, and Arnoud Arntz. 2021. "Patient and Therapist Perspectives on Treatment for Adults with PTSD from Childhood Trauma" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 5: 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050954

APA StyleBoterhoven de Haan, K. L., Lee, C. W., Correia, H., Menninga, S., Fassbinder, E., Köehne, S., & Arntz, A. (2021). Patient and Therapist Perspectives on Treatment for Adults with PTSD from Childhood Trauma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(5), 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050954