Long-Term Survival and Complication Rates of Porcelain Laminate Veneers in Clinical Studies: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

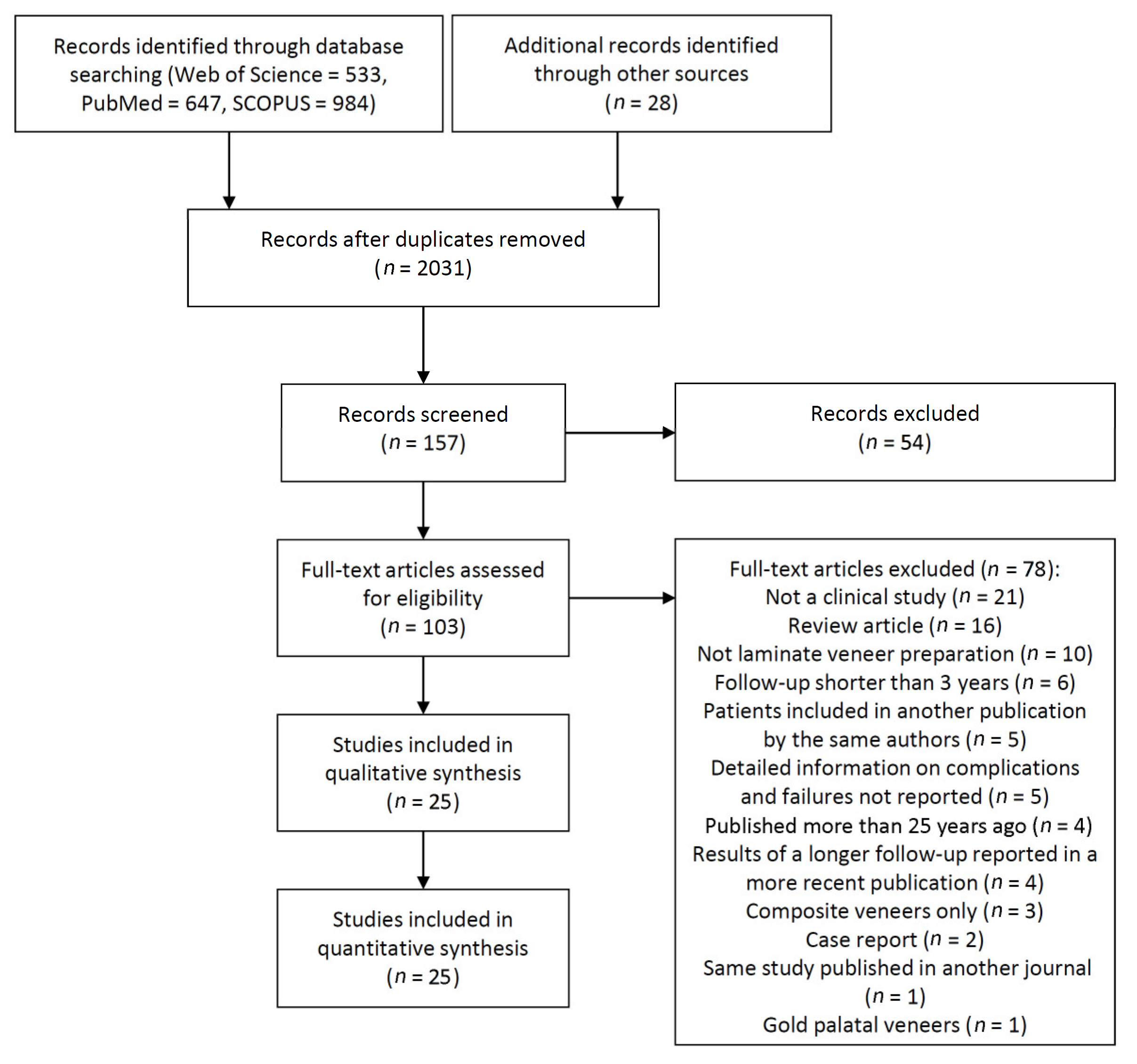

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Description of the Studies and Analyses

| Study | Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 a | 8 | 9 | Total (9/9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaini et al. [29] | 1997 | 9/9 | |||||||||

| Kihn and Barnes [24] | 1998 | 7/9 | |||||||||

| Magne et al. [26] | 2000 | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Sieweke et al. [30] | 2000 | 9/9 | |||||||||

| Aristidis and Dimitra [15] | 2002 | 7/9 | |||||||||

| Shang and Mu [13] | 2002 | 6/9 | |||||||||

| Peumans et al. [6] | 2004 | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Smales and Eternadi [31] | 2004 | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Fradeani et al. [19] | 2005 | 9/9 | |||||||||

| Wiedhahn et al. [32] | 2005 | 9/9 | |||||||||

| Aykor and Ozel [17] | 2009 | 7/9 | |||||||||

| Granell-Ruiz et al. [7] | 2010 | 9/9 | |||||||||

| Beier et al. [5] | 2012 | 7/9 | |||||||||

| D’Arcangelo et al. [18] | 2012 | 9/9 | |||||||||

| Gurel et al. [23] | 2012 | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Layton and Walton [25] | 2012 | 9/9 | |||||||||

| Guess et al. [22] | 2014 | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Nejatidanesh et al. [27] | 2018 | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Rinke et al. [28] | 2018 | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Arif et al. [14] | 2019 | 7/9 | |||||||||

| Aslan et al. [16] | 2019 | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Gresnigt et al. [21] | 2019a | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Gresnigt et al. [20] | 2019b | 8/9 | |||||||||

| Imburgia et al. [12] | 2019 | 6/9 | |||||||||

| Faus-Matoses et al. [33] | 2020 | 8/9 |

| Authors | Published | Study Design/Setting/Operators (n) | Patients (Men/Women) (n) | Patients’ Age Range (Average) (Years) | Country, Recruitment Period of the Patients | Follow-Up | Failed/Placed Veneers (n) | Incisal Coverage (Y/N) | Preparation Design | Definition of Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaini et al. [29] | 1997 | RS/University/Several | 104 (34/70) | 14–71 (29.6♂, 34.4♀) | United Kingdom, 1984–1992 | <78 mo | 122/372 | No | In 90% of the veneered teeth, no form of tooth preparation was undertaken. In the remainder, tooth preparation was of a minimal labial and occasionally proximal enamel reduction. | Those that presented with problems that were not viable to repair and required remaking or changing to an alternative treatment. This group included fractured restorations and debonded restorations that were either fractured and had to be replaced, or intact, which were re-cemented. It also included discolored restorations and restorations not acceptable to the patient due to their appearance or bulk. |

| Kihn and Barnes [24] | 1998 | PS/University/1 | 12 (NM) | NM | USA, NM | 48 mo | 0/59 | Yes | The labial surfaces were reduced by 0.5 mm. An incisal was prepared by 1.5 mm. | NM |

| Magne et al. [26] | 2000 | RS/University/NM | 16 (5/11) | 18–52 (33) | Switzerland, 1992–1996 | 36–84 mo (mean 54) | 7/48 | Yes | 1.5-mm incisal clearance. A facial and proximal light chamfer was created in the form of a paragingival margin respecting the scalloped gingival contour. | Porcelain failures (cracks, chipping, and fractures) |

| Sieweke et al. [30] | 2000 | RS/University/6 | 17 (NM) | 24–69 (45) | Germany, 1992–2000 | 3–95 mo (mean 81) | 8/36 | Yes | A 1-mm-thick layer of dental tissue, i.e., the space required for the material, needs to be removed. | Reasons for failure were: fracture in the ceramic material, fracture of the adhesive bond, and loss of function. |

| Aristidis and Dimitra [15] | 2002 | RS/NM/1 | 61 (23/38) | 18–70 (NM) | Greece, 1993–1994 | 60 mo | 1/186 | Yes | The facial enamel reduced by 0.3 to 0.5 mm. An incisal reduction of 0.5 mm was performed. | Fracture. |

| Shang and Mu [13] | 2002 | RS/NM/NM | 184 (NM) | 18–65 (NM) | China, NM | 60 mo | 28/736 | NM | NM | Unsuccessful restorations include: caries, gum teeth, pathological changes, broken or cracked restorations, fallen off restoration, discoloration, unpleasant appearance. |

| Peumans et al. [16] | 2004 | PS/NM/1 | 25 (8/17) | 19–69 (NM) | Belgium, 1990–1991 | 60–120 mo | 2/87 | Yes | Labial enamel reduction was between 0.3 and 0.7 mm. The incisal edge was shortened and a shoulder was prepared on the palatal side over a distance of 2 to 3 mm. | The failures were recorded as “clinically unacceptable but repairable” and as “clinically unacceptable with replacement needed”. |

| Smales and Eternadi [31] | 2004 | RS/Private/2 | 50 (NM) | >16 | Australia, 1989–1993 | <84 mo (mean 48) | 9/110 | No (n = 64) Yes (n = 46) | Minimal (within enamel). | Color mismatch, fracture, debonding. |

| Fradeani et al. [19] | 2005 | RS/Private/2 | 46 (17/29) | 19–66 (36.8♂, 38.3♀) | Italy, 1991–2002 | Mean 68.3 mo | 5/182 | Yes | 0.3 to 0.6 mm in the cervical third to 0.8 to 1.0 mm in the incisal third. The incisal reduction was 2 mm, | Porcelain fracture and/or partial debonding that exposed the tooth structure and/or impaired esthetic quality or function were the main criteria for irreparable failure. |

| Wiedhahn et al. [32] | 2005 | RS/Private/1 | 260 (99/161) | NM (43.9) | Germany, 1989–1997 | 13–114 mo (mean 56.4) | 14/617 | Up to 1/3 incisal overlap (n = 410), more than 1/3 incisal overlap (n = 39), no incisal coverage (n = 168) | NM | NM |

| Aykor and Ozel [17] | 2009 | PS/NM/NM | 30 (NM) | 28–54 (NM) | Turkey, NM | 60 mo | 0/300 | Yes | Labial enamel reduced approximately 0.75 mm. Butt-joint preparation was performed at the incisal edge. Cervical preparation was finished supragingivally. | NM |

| Granell-Ruiz et al. [7] | 2010 | RS/University/Several | 70 (17/53) | 18–74 (46) | Spain, 1995–2003 | 36–132 mo | 42/323 | Yes (n = 199) No (n = 124) | Of simple design, covering only the vestibular surface of the tooth (n = 124), covering the incisal edge and part of the palatal/lingual side of the tooth with 1 mm height palatal chamfer (n = 199). | The main criteria used in defining the failure of the veneer were the fracture of the porcelain and/or the unbonding. |

| Beier et al. [5] | 2012 | RS/University/2 | 84 (38/46) | NM (44) | Austria, 1987–2009 | Mean 188 mo | 29/318 | Yes and no | Minimal preparation. | An irreparable problem. |

| D’Arcangelo et al. [18] | 2012 | RS/University/1 | 30 (13/17) | 18–55 (35♂, 31♀) | Italy, 2002–2003 | <84 mo | 3/119 | Yes | Ceramic thickness in the middle third of 0.7 mm and incisal ceramic thickness of 1.5 mm. Proximal preparation was ended at the contact area. | Absolute failure was defined as clinically unacceptable fractures and cracks, which required replacement of the entire restoration, and/or secondary caries, as well as endodontic complications. |

| Gurel et al. [23] | 2012 | RS/Private/1 | 66 (19/47) | 23–73 (NM) | Turkey, 1997–2009 | <144 mo | 42/580 | Yes | Tooth preparation through the aesthetic pre-evaluative APT technique. | Fracture/chipping, debonding, microleakage secondary caries, sensitivity, and postoperative root canal treatment. |

| Layton and Walton [25] | 2012 | PS/Private/1 | 155 (28/127) | 15–73 (41) | Australia, 1990–2010 | <256 mo | 17/499 | Yes | Chamfer margins, incisal reduction, palatal overlap, and at least 80% enamel. | Part or all of the prosthesis was lost, the original marginal integrity of the restorations and teeth was modified, or the restoration lost retention more than once. |

| Guess et al. [22] | 2014 | PS/University/NM | 25 (13/12) | 19–64 (45♂, 43♀) | Germany, 2000–2003 | <84 mo | 2/66 | Yes | Forty-two overlap restorations (incisal edge reduction: 0.5 to 1.5 mm; palatal butt-joint margin) and 24 full veneer restorations (0.5- to 0.7-mm palatal rounded shoulder margin) were investigated. Both designs had a buccal (0.5 mm) and proximal (0.5 to 0.7 mm) chamfer preparation. | Absolute failures: unacceptable fractures, secondary caries, and endodontic complications. Relative failures: minimal cohesive acceptable fractures, loss of adhesion, and Charlie ratings in any of the United States Public Health Service criteria. |

| Nejatidanesh et al. [27] | 2018 | RS/University/Several | 71 (17/54) | 19–62 (34.9) | Iran, 2009 | 60 mo | 2/197 | Yes | Labial reduction of 0.5–0.7mm with a long chamfer supra-gingival margin and incisal butt joint reduction of 0.5–1.0 mm. | Porcelain fracture, debonding (which cannot rebond) and unacceptable esthetic quality or function were defined as a failure. Moreover, when the abutment tooth was extracted following a biologic complication (root fracture, endodontic and/or periodontal problems). |

| Rinke et al. [28] | 2018 | RS/Private/1 | 31 (11/20) | 23–70 (46.1) | Germany, 2002–2008 | <250.9 mo (mean 93.3) | 12/101 | Yes | Labial chamfer (minimum preparation depth: 0.3 mm) and a labial reduction of at least 0.5 mm. The incisal reduction was at least 1.0 mm. | Absolute failure was defined as a clinically unacceptable fracture of the ceramic or a biological event (caries, tooth fracture, periodontal reason) that required a replacement of the entire restoration or tooth extraction |

| Arif et al. [14] | 2019 | RS/University/Several | 26 (7/19) | NM (53) | USA, 1999–2006 | 84–168 mo | 5/114 | NM | NM | Fracture and partial debonding that either exposes tooth structure, impairs esthetics, or function. |

| Aslan et al. [16] | 2019 | RS/University + Private/3 | 51 (14/37) | 18–68 (34.6) | Turkey, 1998–2012 | 60–252 mo (mean 136) | 15/413 | Yes | 0.3 to 0.5 mm of the thickness of the vestibular surface. An average of 1 to 1.5-mm grooves for the incisal reduction was performed, followed by proximal preparation. | Caries, debonding, chipping, and the fracture considered absolute failures. |

| Gresnigt et al. [21] | 2019a | PS/University/Several | 104 (NM) | 18–78 (42.1) | Netherlands, 2007–2018 | 8–133 mo (mean 55.8) | 19/384 | Yes | The labial surfaces were axially reduced by 0.1 (cervical) to 0.7 mm (mid-height). A flat incisal overlap of 1–1.5mm was obtained. | All veneers which had to be replaced (survival) were considered as absolute failures (caries, fractures, chipping, severe marginal discoloration). |

| Gresnigt et al. [20] | 2019b | RCT/University/1 | 11 (3/8) | 20–69 (54.5) | Netherlands, 2008–2010 | 97–120 mo (mean 97) | 0/24 | Yes | The labial surfaces were axially reduced by 0.3–0.5 mm. An incisal overlap of 1–1.5 mm was prepared on all cases. | Caries, debonding, and fracture to failure were considered as absolute failures. |

| Imburgia et al. [12] | 2019 | RS/Private/NM | 53 (21/32) | NM | Italy, 2009–2015 | 24–105 (mean 54.4) | 1/265 | Yes | The teeth were prepared with a vertical finish line and an overall reduction from 0.2 to 1 mm for the incisal surfaces. | Abutment decay, core fracture, or partial or complete debonding. |

| Faus-Matoses et al. [33] | 2020 | PS/University/2 | 64 (24/40) | NM (52) | Spain, 2009–2014 | Mean 62.4 mo | 35/364 | No | The teeth were prepared without involving the incisal edge, allowing a ceramic thickness of 0.4 to 0.7 mm. | Veneers not present in loco or totally unusable. Fracture or debonding. |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Demarco, F.F.; Collares, K.; Coelho-de-Souza, F.H.; Correa, M.B.; Cenci, M.S.; Moraes, R.R.; Opdam, N.J. Anterior composite restorations: A systematic review on long-term survival and reasons for failure. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintze, S.D.; Rousson, V.; Hickel, R. Clinical effectiveness of direct anterior restorations—A meta-analysis. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequeira-Byron, P.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Carter, B.; Nasser, M.; Alrowaili, E.F. Single crowns versus conventional fillings for the restoration of root-filled teeth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, Cd009109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calamia, J.R. Etched porcelain veneers: The current state of the art. Quintessence Int. 1985, 16, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, U.S.; Kapferer, I.; Burtscher, D.; Dumfahrt, H. Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers for up to 20 years. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2012, 25, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Peumans, M.; De Munck, J.; Fieuws, S.; Lambrechts, P.; Vanherle, G.; Van Meerbeek, B. A prospective ten-year clinical trial of porcelain veneers. J. Adhes. Dent. 2004, 6, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Granell-Ruiz, M.; Fons-Font, A.; Labaig-Rueda, C.; Martínez-González, A.; Román-Rodríguez, J.L.; Solá-Ruiz, M.F. A clinical longitudinal study 323 porcelain laminate veneers. Period of study from 3 to 11 years. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2010, 15, e531–e537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Ghiasi, P.; Kisch, J.; Lindh, L.; Larsson, C. Retrospective study comparing the clinical outcomes of bar-clip and ball attachment implant-supported overdentures. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 62, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Larsson, C. Retrospective evaluation of implant-supported full-arch fixed dental prostheses after a mean follow-up of 10 years. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2020, 31, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Grp, P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH. Quality Assessment Tool for Case Series Studies. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Imburgia, M.; Cortellini, D.; Valenti, M. Minimally invasive vertical preparation design for ceramic veneers: A multicenter retrospective follow-up clinical study of 265 lithium disilicate veneers. Int. J. Esthet. Dent. 2019, 14, 286–298. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, X.; Mu, Y. Clinical application and effective assessment of cerinate porcelain laminate veneers. Chin. Med. J. 2002, 115, 1739–1740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arif, R.; Dennison, J.B.; Garcia, D.; Yaman, P. Retrospective evaluation of the clinical performance and longevity of porcelain laminate veneers 7 to 14 years after cementation. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 122, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristidis, G.A.; Dimitra, B. Five-year clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers. Quintessence Int 2002, 33, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aslan, Y.U.; Uludamar, A.; Ozkan, Y. Clinical performance of pressable glass-ceramic veneers after 5, 10, 15, and 20 years: A retrospective case series study. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2019, 31, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykor, A.; Ozel, E. Five-year clinical evaluation of 300 teeth restored with porcelain laminate veneers using total-etch and a modified self-etch adhesive system. Oper. Dent. 2009, 34, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Arcangelo, C.; De Angelis, F.; Vadini, M.; D’Amario, M. Clinical evaluation on porcelain laminate veneers bonded with light-cured composite: Results up to 7 years. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012, 16, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradeani, M.; Redemagni, M.; Corrado, M. Porcelain laminate veneers: 6- to 12-year clinical evaluation—A retrospective study. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2005, 25, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gresnigt, M.M.M.; Cune, M.S.; Jansen, K.; van der Made, S.A.M.; Özcan, M. Randomized clinical trial on indirect resin composite and ceramic laminate veneers: Up to 10-year findings. J. Dent. 2019, 86, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresnigt, M.M.M.; Cune, M.S.; Schuitemaker, J.; van der Made, S.A.M.; Meisberger, E.W.; Magne, P.; Özcan, M. Performance of ceramic laminate veneers with immediate dentine sealing: An 11 year prospective clinical trial. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guess, P.C.; Selz, C.F.; Voulgarakis, A.; Stampf, S.; Stappert, C.F. Prospective clinical study of press-ceramic overlap and full veneer restorations: 7-year results. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2014, 27, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurel, G.; Morimoto, S.; Calamita, M.A.; Coachman, C.; Sesma, N. Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers: Outcomes of the aesthetic pre-evaluative temporary (APT) technique. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2012, 32, 625–635. [Google Scholar]

- Kihn, P.W.; Barnes, D.M. The clinical longevity of porcelain veneers: A 48-month clinical evaluation. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1998, 129, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layton, D.M.; Walton, T.R. The up to 21-year clinical outcome and survival of feldspathic porcelain veneers: Accounting for clustering. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2012, 25, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Magne, P.; Perroud, R.; Hodges, J.S.; Belser, U.C. Clinical performance of novel-design porcelain veneers for the recovery of coronal volume and length. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. Dent. 2000, 20, 440–457. [Google Scholar]

- Nejatidanesh, F.; Savabi, G.; Amjadi, M.; Abbasi, M.; Savabi, O. Five year clinical outcomes and survival of chairside CAD/CAM ceramic laminate veneers—A retrospective study. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2018, 62, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, S.; Pabel, A.K.; Schulz, X.; Rödiger, M.; Schmalz, G.; Ziebolz, D. Retrospective evaluation of extended heat-pressed ceramic veneers after a mean observational period of 7 years. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaini, F.J.; Shortall, A.C.; Marquis, P.M. Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers. A retrospective evaluation over a period of 6.5 years. J. Oral Rehabil. 1997, 24, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieweke, M.; Salomon-Sieweke, U.; Zöfel, P.; Stachniss, V. Longevity of oroincisal ceramic veneers on canines--a retrospective study. J. Adhes. Dent. 2000, 2, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smales, R.J.; Etemadi, S. Long-term survival of porcelain laminate veneers using two preparation designs: A retrospective study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2004, 17, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wiedhahn, K.; Kerschbaum, T.; Fasbinder, D.F. Clinical long-term results with 617 Cerec veneers: A nine-year report. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2005, 8, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Faus-Matoses, V.; Ruiz-Bell, E.; Faus-Matoses, I.; Özcan, M.; Salvatore, S.; Faus-Llácer, V.J. An 8-year prospective clinical investigation on the survival rate of feldspathic veneers: Influence of occlusal splint in patients with bruxism. J. Dent. 2020, 99, 103352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layton, D.M. Understanding Kaplan-Meier and survival statistics. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2013, 26, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.G. Life tables for clinical scientists. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 1992, 3, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S.Y.; Bennani, V.; Aarts, J.M.; Lyons, K. Incisal preparation design for ceramic veneers: A critical review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2018, 149, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loguercio, A.D.; Moura, S.K.; Pellizzaro, A.; Dal-Bianco, K.; Patzlaff, R.T.; Grande, R.H.; Reis, A. Durability of enamel bonding using two-step self-etch systems on ground and unground enamel. Oper. Dent. 2008, 33, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, F.L.; Colucci, V.; Palma-Dibb, R.G.; Corona, S.A. Assessment of in vitro methods used to promote adhesive interface degradation: A critical review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2007, 19, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanesi, R.B.; Pigozzo, M.N.; Sesma, N.; Laganá, D.C.; Morimoto, S. Incisal coverage or not in ceramic laminate veneers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 2016, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, N.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Wu, S.; Li, Y. Effect of Preparation Designs on the Prognosis of Porcelain Laminate Veneers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oper. Dent. 2017, 42, E197–E213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kelly, J.R. Dental Ceramics for Restoration and Metal Veneering. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 61, 797–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, G.; Boberick, K.; McCool, J. Fatigue of restorative materials. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2001, 12, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini, N.P.; Aguiar, F.H.; Lima, D.A.; Lovadino, J.R.; Terada, R.S.; Pascotto, R.C. Advances in dental veneers: Materials, applications, and techniques. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2012, 4, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peumans, M.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Yoshida, Y.; Lambrechts, P.; Vanherle, G. Porcelain veneers bonded to tooth structure: An ultra-morphological FE-SEM examination of the adhesive interface. Dent. Mater. 1999, 15, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresnigt, M.M.; Kalk, W.; Özcan, M. Clinical longevity of ceramic laminate veneers bonded to teeth with and without existing composite restorations up to 40 months. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumfahrt, H.; Schäffer, H. Porcelain laminate veneers. A retrospective evaluation after 1 to 10 years of service: Part II—Clinical results. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2000, 13, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, S.; Landahl, I.; Stegersjö, G.; Milleding, P. A clinical evaluation of ceramic laminate veneers. Int. J. Prosthodont. 1992, 5, 447–451. [Google Scholar]

- Granell-Ruíz, M.; Agustín-Panadero, R.; Fons-Font, A.; Román-Rodríguez, J.L.; Solá-Ruíz, M.F. Influence of bruxism on survival of porcelain laminate veneers. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2014, 19, e426–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsel, R.P.; Lin, D. Retrospective analysis of porcelain failures of metal ceramic crowns and fixed partial dentures supported by 729 implants in 152 patients: Patient-specific and implant-specific predictors of ceramic failure. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2009, 101, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. Bruxism and dental implant failures: A multilevel mixed effects parametric survival analysis approach. J. Oral Rehabil. 2016, 43, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. Bruxism and dental implant treatment complications: A retrospective comparative study of 98 bruxer patients and a matched group. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2017, 28, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Larsson, C. Analysis of technical complications and risk factors for failure of combined tooth-implant-supported fixed dental prostheses. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2020, 22, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Larsson, C. Retrospective clinical evaluation of 2- to 6-unit implant-supported fixed partial dentures: Mean follow-up of 9 years. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat Res. 2020, 22, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Larsson, C. Retrospective clinical evaluation of implant-supported single crowns: Mean follow-up of 15 years. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2019, 30, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jüni, P.; Holenstein, F.; Sterne, J.; Bartlett, C.; Egger, M. Direction and impact of language bias in meta-analyses of controlled trials: Empirical study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alenezi, A.; Alsweed, M.; Alsidrani, S.; Chrcanovic, B.R. Long-Term Survival and Complication Rates of Porcelain Laminate Veneers in Clinical Studies: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10051074

Alenezi A, Alsweed M, Alsidrani S, Chrcanovic BR. Long-Term Survival and Complication Rates of Porcelain Laminate Veneers in Clinical Studies: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(5):1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10051074

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlenezi, Ali, Mohammad Alsweed, Saleh Alsidrani, and Bruno R. Chrcanovic. 2021. "Long-Term Survival and Complication Rates of Porcelain Laminate Veneers in Clinical Studies: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 5: 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10051074

APA StyleAlenezi, A., Alsweed, M., Alsidrani, S., & Chrcanovic, B. R. (2021). Long-Term Survival and Complication Rates of Porcelain Laminate Veneers in Clinical Studies: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(5), 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10051074