Abstract

The available meta-analyses have inconclusively indicated the advantages of video-laryngoscopy (VL) in different clinical situations; therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine efficacy outcomes such as successful first attempt or time to perform endotracheal intubation as well as adverse events of VL vs. direct laryngoscopes (DL) for double-lumen intubation. First intubation attempt success rate was 87.9% for VL and 84.5% for DL (OR = 1.64; 95% CI: 0.95 to 2.86; I2 = 61%; p = 0.08). Overall success rate was 99.8% for VL and 98.8% for DL, respectively (OR = 3.89; 95%CI: 0.95 to 15.93; I2 = 0; p = 0.06). Intubation time for VL was 43.4 ± 30.4 s compared to 54.0 ± 56.3 s for DL (MD = −11.87; 95%CI: −17.06 to −6.68; I2 = 99%; p < 0.001). Glottic view based on Cormack–Lehane grades 1 or 2 equaled 93.1% and 88.1% in the VL and DL groups, respectively (OR = 3.33; 95% CI: 1.18 to 9.41; I2 = 63%; p = 0.02). External laryngeal manipulation was needed in 18.4% cases of VL compared with 42.8% for DL (OR = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.40; I2 = 69%; p < 0.001). For double-lumen intubation, VL offers shorter intubation time, better glottic view based on Cormack–Lehane grade, and a lower need for ELM, but comparable first intubation attempt success rate and overall intubation success rate compared with DL.

1. Introduction

The increasing development of thoracoscopic procedures is inevitably associated with the use of single-lung ventilation. Such a strategy allows, on one hand, to expose the surgical field while maintaining ventilation of the non-operated lung [1]. One of several methods of providing single-lung ventilation, currently considered the gold standard, is the use of double-lumen endotracheal tubes (DLTs) [2]. The application of DLTs, due to their large diameter or the need for a rotational insertion technique, is associated with a significant risk of prolonged intubation, intubation failure, and airway trauma [3,4]. On the other hand, studies have confirmed that the use of video-laryngoscopes (VL), compared with traditional laryngoscopy, improves the visibility of anatomical structures during intubation [5]. VLs facilitate intubation with a traditional tube in cases of both “normal” and difficult airways [6]. However, the available meta-analyses have inconclusively indicated the advantages of VL in different clinical situations [7,8,9,10].

Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the efficacy outcomes such as successful first attempt and time to perform endotracheal intubation as well as adverse events of VLs vs. direct laryngoscopes (DL) for double-lumen intubation.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the criteria outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Table S2) [11]. Due to the study design (meta-analysis), neither institutional review board approval nor patient informed consents were required.

2.1. Search Strategy

Two reviewers (KK and JS) independently performed a comprehensive literature search using the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases. The most recent search was conducted on 30 September 2021. Terms related to double-lumen endotracheal intubation were applied: “double-lumen”, “laryngoscopy”, “video-laryngoscopy”, and “direct laryngoscopy”. Additionally, we performed a manual search and review of the references listed in the retrieved articles. All references were saved in an EndNote (EndNote, Inc., Philadelphia, PA, USA) library used to identify duplicates.

2.2. Study Selection Criteria

The studies included in this meta-analysis met the following PICOS criteria: (1) Participants: intubated adult patients; (2) Intervention: endotracheal intubation by using a DLT with video-laryngoscopes; (3) Comparison: endotracheal intubation by using a DLT with Macintosh direct laryngoscope; (4) Outcomes: detailed information concerning first intubation attempt success rate, overall intubation success rate, intubation time, glottic view, external laryngeal manipulation (ELM), and adverse events; and (5) Study design: randomized controlled trials. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies involving pediatric patients; (2) non-RCTs; (3) editorials; (4) conference abstracts; and (5) guidelines.

2.3. Data Extraction

Two reviewers (MC and KK) independently extracted data from the identified eligible studies by using a specifically designed data extraction form in Microsoft ExcelTM (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Another author cross-checked these data before analysis (LS).

The following data were extracted from each study: first intubation attempt success rate, overall intubation success rate, intubation time, glottic view, and ELM. We also analyzed the adverse events that occurred during tracheal intubation. Where there were suspected discrepancies in the data, we contacted the relevant authors directly.

2.4. Risk of Assessment Bias

We applied a revised tool to assess the risk of bias in randomized trials (RoB-2) [12] to evaluate the risk of bias of the included studies. The RoB-2 tool examines five bias domains: (1) bias arising from the randomization process; (2) bias due to deviations from intended intervention; (3) bias due to missing outcome data; (4) bias in the measurement of the outcome; and (5) bias in the selection of the reported results. The risk of bias in each of these domains can be rated as “high”, “some concerns”, or “low”. The overall RoB-2 judgment at the domain and study level was attributed in accordance with the criteria specified in the RobVis tool [13]. The risk of bias was determined independently by two reviewers (KK and MC); disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (LS) if necessary.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The meta-analysis was entirely conducted with Review Manager software, version 5.4 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) and the Stata 14 software (StataCorp. LP, College Station, TX, USA). The significance level for all statistical tests was p < 0.05 (two-tailed). For dichotomous data, we used odds ratios (ORs) as the effect measure with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and for continuous data, we applied mean differences (MDs) with 95% CI. When a continuous outcome was reported in a study as median, range, and interquartile range, we estimated means and standard deviations with the use of a formula described by Hozo et al. [14]. For meta-analysis, we utilized the random effects model (assuming a distribution of effects across studies) to weigh estimates of studies in proportion to their significance [15]. Heterogeneity was determined with the I2 statistic, in which the results ranged from 0% to 100%. Heterogeneity was interpreted as not observed when I2 = 0%, low when I2 = 25%, medium when I2 = 50%, and high when I2 = 75% [16,17].

Subgroup analyses were performed on first intubation success rate, overall success rate, time to intubation; glottic view, and ELM were investigated by separating the VL types. Videolaryngoscopes, depending on the construction, were divided into the following groups: Macintosh blade VLs, channeled VLs, and video-tubes and scopes.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

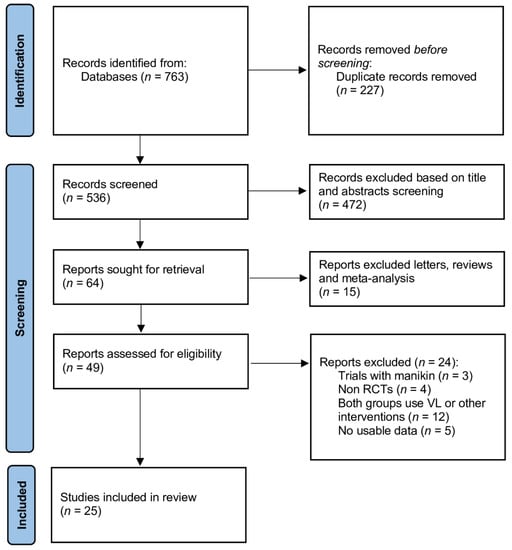

The initial literature search yielded 761 citations, and further two citations were identified through manual citation and a reference search of relevant articles (Figure 1). After excluding duplicate studies, 539 articles remained. After screening the titles and abstracts of all the retrieved articles, 473 papers were excluded. Then, the full texts were reviewed, and 32 studies were excluded because they did not involve Macintosh direct laryngoscope as a comparator group, consisted of manikin trials, involved different interventions, or were reviews or meta-analyses. Ultimately, 25 studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] published in the period of 2010–2021 were included in this meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Database search and selection of studies according to PRISMA guidelines.

These 25 studies included 2154 adult patients (Table 1 and Table S1). A detailed characterization of the patients in the VL and DL groups is presented in Supplementary Digital File in Table S3 and Figures S1 and S2. Each study was screened for risk of bias and for methodological quality with the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias (Figures S5 and S6). All studies met the criteria for high-quality randomized controlled trials.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of the included studies.

3.2. First Intubation Attempt Success Rate

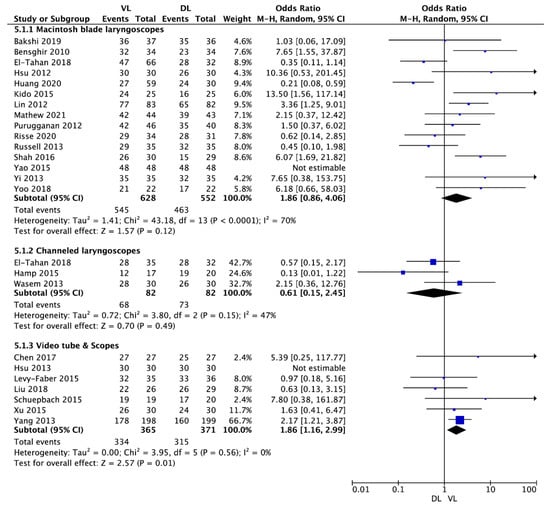

A total of 23 studies reported the first intubation attempt success rate. Pooled analysis revealed the first attempt success rate of 87.9% in VL compared with 84.5% for DL (OR = 1.64; 95% CI: 0.95 to 2.86; I2 = 61%; p = 0.08).

Subgroup analysis showed that the first intubation success rate for VL with a Macintosh shape blade compared with the standard Macintosh laryngoscope varied and amounted to 85.9% and 83.6%, respectively (OR = 1.93; 95% CI: 0.82 to 4.51; I2 = 72%; p = 0.13; Figure 2). In turn, intubation with video tubes or scopes was associated with a statistically significantly higher first intubation success rate than intubation with DL (91.5% vs. 84.9%) (OR = 1.86; 95% CI: 1.16 to 2.99; I2 = 0%; p = 0.01). An inverse relationship was observed in the subgroup of channeled laryngoscopes: intubation with these devices compared with DL was associated with a lower first intubation success rate (82.9% vs. 89.0%) (OR = 0.61; 95% CI: 0.15 to 2.45; I2 = 47%; p = 0.49).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of first intubation attempt success rate among video-laryngoscope and direct-laryngoscope groups. The center of each square represents the weighted odds ratios for individual trials, and the corresponding horizontal line stands for a 95% confidence interval. The diamonds represent pooled results. Legend: CI = confidence interval; DL = direct laryngoscopy; OD = odds ratio; VL = video-laryngoscopy.

3.3. Overall Intubation Success Rate

Overall success rate was reported in 16 studies and equaled 99.8% for VL and 98.8% for DL (OR = 3.89; 95% CI: 0.95 to 15.93; I2 = 0; p = 0.06).

Subgroup analysis established a 100% overall intubation success rate for VL with a Macintosh shaped blade and for DL. Additionally, for channeled laryngoscopes and DL comparison, the overall success rate was 100% in both groups. On the other hand, the overall success rate with video tubes and scopes turned out to be 99.4% compared with 97.5% for DL (OR = 3.89; 95% CI: 0.95 to 15.93; I2 = 0%; p = 0.06).

3.4. Intubation Time

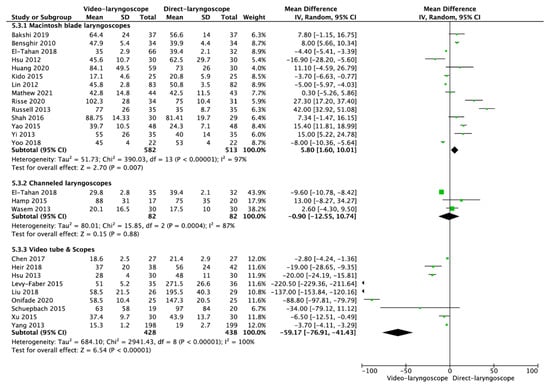

Mean intubation time for VL equaled 43.4 ± 30.4 s and was statistically significantly shorter than that with DL: 54.0 ± 56.3 s (MD = −11.87; 95% CI: −17.06 to −6.68; I2 = 99%; p < 0.001).

In the Macintosh blade laryngoscope subgroup, mean time of intubation amounted to 55.7 ± 30.4 s for VL and 48.6 ± 21.2 s for DL (MD = 5.80; 95% CI: 1.60 to 10.01; I2 = 97%; p = 0.007; Figure 3). In the channeled laryngoscope subgroup, intubation time was 38.3 ± 31.0 s for VL compared with 40.1 ± 28.5 s for DL (MD = −0.90; 95% CI: −12.55 to 10.74; I2 = 87%; p = 0.88). In the subgroup of video tubes and scopes, mean intubation time with VL equaled 28.3 ± 22.2 s and was statistically significantly shorter than that with DL: 65 ± 82.2 s (MD = −59.17; 95% CI: −76.91 to −41.43; I2 = 100%; p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of time to intubation in video-laryngoscope and direct-laryngoscope groups. The center of each square represents the weighted mean differences for individual trials, and the corresponding horizontal line stands for a 95% confidence interval. The diamonds represent pooled results. Legend: CI = confidence interval; MD = mean difference.

3.5. Glottic View

Glottic view in accordance with Cormack–Lehane grade was reported in 15 studies. Good view, defined as Cormack–Lehane grade 1 or 2, varied in the VL and DL groups and equaled 93.1% and 88.1%, respectively (OR = 3.33; 95% CI: 1.18 to 9.41; I2 = 63%; p = 0.02).

In the Macintosh blade subgroup analysis, VL resulted in better visualization of the glottis than DL (96.5% vs. 87.8%) (OR = 5.40; 95% CI: 1.99 to 14.66; I2 = 45%; p < 0.001; Figures S3 and S4). The same relationship was observed in the channeled VL subgroup (75.6% vs. 63%, respectively) (OR = 4.78; 95% CI: 0.17 to 135.25; I2 = 80%; p = 0.36).

In the subgroup of video tubes and scopes, glottic visualization at Cormack–Lehane category grades 1–2 was observed in 92.9% for VL and 93.5% for DL (OR = 0.94; 95% CI: 0.30 to 2.99; I2 = 0%; p = 0.92).

3.6. External Laryngeal Manipulation

Ten studies reported ELM during the intubation process. Pooled analysis revealed that ELM was needed in 18.4% cases of VL compared with 42.8% in the DL group (OR = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.40; I2 = 69%; p < 0.001).

Subgroup analysis showed that ELM was less often required with VL than with DL in the Macintosh blade VL group (21.4% vs. 44.3%) (OR = 0.27; 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.60; I2 = 74%; p = 0.001), the channeled VL group (10.8% vs. 29.0%) (OR = 0.23; 95% CI: 0.03 to 1.97; I2 = 54%; p = 0.18), and the group of video tubes and scopes (0% vs. 46.7%) (OR = 0.02; 95% CI: 0.00 to 0.33; p = 0.007).

3.7. Adverse Events

Intubation with VL and DL exhibited a comparable rate of adverse events. A full list of the analyzed adverse events is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pooled analysis of adverse events reported in the included trials.

4. Discussion

The analysis of the success rate of the first intubation attempt, described in 26 studies (n = 2154), showed higher values in the VL group than for DL. However, there was no statistical significance, but only a trend toward significance (p = 0.07). These results contrasted with the data obtained by Liu et al., who investigated 1215 patients and confirmed a significant superiority of video devices (VL or video-stylet) over Macintosh laryngoscope (OR = 2.77; 95% CI: 1.92 to 4.00; p < 0.00001) [43]. The same authors showed no differences in subgroup analysis depending on the type of the video device used. In contrast, they maintained that intubation with video tubes or scopes was associated with a statistically significantly higher first attempt success rate than intubation with DL. An analysis of the total intubation success and failure rates revealed no significant differences between VL and DL (p = 006). However, the involved 17 randomized clinical trials exhibited low homogeneity values. Endotracheal intubation with DLTs, due to their specificity, is more difficult than that with standard equipment; therefore, it is important to maximize the probability of intubation, especially during the first attempt. For this purpose, the use of video tubes or scopes is recommended first.

One of the fundamental factors of perioperative safety is the duration of endotracheal intubation. Prolonged apnea time can lead to significant hypoxia with its consequences. Patients undergoing thoracic surgery are special cases. On one hand, they usually present with pulmonary diseases (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchial asthma, pneumoconiosis), which are initially associated with a high risk of hypoxemia and low oxygen reserve. As mentioned earlier, the use of DLT is a priori associated with prolonged intubation due to the device specificity. Our meta-analysis confirmed the superiority of VL over DL for significantly shorter DLT intubation times. It should be noted that differences in intubation time are unsure due to the very high heterogeneity of the data (I2 > 90%) and this problem also applies to other meta-analyses. Different data were provided by Liu et al., who demonstrated no significant difference in intubation time between any video device and the Macintosh laryngoscope [43]. This, as the authors themselves indicate, may have been influenced by a high level of heterogeneity when reporting intubation times across randomized controlled trials. In our study, as in the analysis by Kim et al., the use of video tubes or scopes was associated with significantly shorter intubation times [44].

The safety of endotracheal intubation and occurrence of adverse events are particularly influenced by the degree of laryngeal visualization and the need for external manipulation within the larynx. The use of VL allowed better glottic visualization (rated 1 and 2 on the Cormack–Lehane scale), and the need for ELM was described significantly less often. Subgroup analysis showed no need for ELM with video tubes or scopes.

DLT intubation involves several consecutive steps. First, the laryngeal entry is visualized; then, the bronchial tip is inserted behind the vocal cords; the tube is advanced toward the tracheal bifurcation; and, finally, the bronchial end of the tube is placed in the appropriate main bronchus [45]. The duration of this procedure is significantly longer than that of single-tube intubation and depends on many factors including visualization of the laryngeal entry. The technique is also associated with a higher risk of adverse events. Perioperative oral trauma with bleeding, damage to teeth and cheeks, distention, bronchospasm, and cardiac arrhythmias as well as postoperative sore throat and hoarseness are some of the complications related to endotracheal intubation [46,47]. During intubation with DLT, the risk of these complications is significantly higher, and esophageal intubation or tube displacement are particularly associated with this procedure [46]. In the material analyzed, DL was related to a higher risk of unintended esophageal intubation and, at the same time, a lower risk (but not statistically significant, p = 0.06) of tube misplacement. However, the homogeneity of the randomized controlled trials included in the study was low. The presented data are consistent with those provided by Liu et al., who confirmed that the use of VL was associated with a higher incidence of tube misplacement [43]. The occurrence of other adverse events such as oral bleeding, bronchospasm, sore throat, hoarseness, desaturation, cardiac arrhythmia, lip trauma, dental trauma, and cuff rupture was not associated with any of the intubation techniques used. These results, when compared with the available meta-analyses, are conflicting. In both studies by Liu et al. [43] and Kim et al. [44], the use of VL brought about a lower risk of intubation complications. Of these, the use of video-stylets was associated with a lower incidence of the described adverse events [44]. These discrepancies may be influenced by, among other factors, the lack of particular VL subgroup analysis in our study.

There are some limitations of our study that should be considered. These are due to several factors that affect the obtained results. The first limitation is the relatively small study group in most of the analyzed publications. Another problem is that in the majority of the publications, only patients with normal airways were included and studies were limited to a specific patient population. In some studies, intubation was performed by physicians experienced in endotracheal intubation. Another limitation is the use of specific types of DLTs. Moreover, it should be mentioned that due to the small number of studies using channeled-laryngoscopes, the conclusions on channeled-laryngoscopes were based on only 82 patients.

5. Conclusions

For double-lumen endotracheal intubation, VL offers shorter intubation time, better glottic view in accordance with Cormack–Lehane grade, and lower need for ELM, but comparable first intubation attempt success rate and overall intubation success rate compared with DL.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm10235524/s1, Table S1: Methodology characteristics among the included trials, Table S2: PRISMA Checklist, Table S3: Polled analysis of patient characteristics, Figure S1: Distribution of American Society of Anesthesiologists grades among 1305 patients, Figure S2: Distribution of Mallampati class among 1795 patients, Figure S3: Forest plot of Cormack–Lehane grades 1 or 2 in video-laryngoscope and direct-laryngoscope groups, Figure S4: Distribution of glottis visualization in Cormack–Lehane grades among 1500 patients, Figure S5: A summary table of the review authors’ judgements for each risk of bias item for each randomized study, Figure S6: A plot of the distribution of the review authors’ judgements across randomized studies for each risk of bias item.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. and L.S.; Methodology, K.K. and L.S.; Software, J.C. and G.N.-S.; Validation, L.S., J.S. and K.K.; Formal analysis, K.K., S.B. and J.R.L.; Investigation, K.K., L.S., M.P. and P.W.; Resources, L.S. and M.C.; Data curation, K.K. and L.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, K.K., S.B., J.S. and L.S.; Writing—review and editing, F.W.P. and the rest of the authors; Visualization, K.K. and L.S.; Supervision, L.S.; Project administration, K.K.; Funding acquisition, J.R.L. and L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the ERC Research Net and by the Polish Society of Disaster Medicine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rapchuk, I.L.; Kunju, S.; Smith, I.J.; Faulke, D.J. A six-month evaluation of the VivaSightTM video double-lumen endotracheal tube after introduction into thoracic anaesthetic practice at a single institution. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2017, 45, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karczewska, K.; Smereka, J.; Szarpak, L.; Ruetzler, K.; Bialka, S. Efficacy of double-lumen intubation performed by paramedics on patients with lung damage. Experimental, pilot simulation trial. Disaster Emerg. Med. J. 2020, 5, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Ran, L.; Story, D.A. Sore throat or hoarse voice with bronchial blockers or double-lumen tubes for lung isolation: A randomized, prospective trial. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2009, 37, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Jahr, J.S.; Sullivan, E.; Waters, P.F. Tracheobronchial rupture after double-lumen endotracheal intubation. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2004, 18, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smereka, J.; Ladny, J.R.; Naylor, A.; Ruetzler, K.; Szarpak, L. C-MAC compared with direct laryngoscopy for intubation in patients with cervical spine immobilization: A manikin trial. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 35, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szarpak, L.; Smereka, J.; Ladny, J.R. Comparison of Macintosh and Intubrite laryngoscopes for intubation performed by novice physicians in a difficult airway scenario. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 35, 796–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppan, L.; Tramer, M.R.; Niquille, M.; Grosgurin, O.; Marti, C. Alternative intubation techniques vs Macintosh laryngoscopy in patients with cervical spine immobilization: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 116, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, H. Pediatric video laryngoscope versus direct laryngoscope: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pediatr. Anesth. 2014, 24, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, A.; Molinari, N.; Conseil, M.; Coisel, Y.; Pouzeratte, Y.; Belafia, F.; Jung, B.; Chanques, G.; Jaber, S. Video laryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for orotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Care Med. 2017, 40, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslanka, M.; Smereka, J.; Proc, M.; Robak, O.; Attila, K.; Szarpak, L.; Ruetzler, K. Airtraq® versus Macintosh laryngoscope for airway management during general anesthesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Disaster Emerg. Med. J. 2021, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Syn. Meth. 2020, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozo, S.P.; Djulbegovic, B.; Hozo, I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2005, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2019. Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szarpak, L.; Rafique, Z.; Gasecka, A.; Chirico, F.; Gawel, W.; Hernik, J.; Kaminska, H.; Filipiak, K.J.; Jaguszewski, M.J.; Szarpak, L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of effect of vitamin D levels on the incidence of COVID-19. Cardiol. J. 2021, 28, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakshi, S.G.; Gawri, A.; Divat, J.V. McGrath MAC video laryngoscope versus direct laryngoscopy for the placement of double-lumen tubes: A randomised control trial. Indian J. Anaesth. 2019, 63, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensghir, M.; Alaoui, H.; Azendour, H.; Drissi, M.; Elwali, A.; Meziane, M.; Lalaoui, J.S.; Akhaddar, A.; Kamili, K.D. Faster double-lumen tube intubation with the videolaryngoscope than with a standard laryngoscope. Can. J. Anaesth. 2010, 57, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.T.; Ting, C.K.; Lee, M.Y.; Cheng, H.W.; Chan, K.H.; Chang, W.K. A randomised trial comparing real-time double-lumen endobronchial tube placement with the Disposcope® with conventional blind placement. Anaesthesia 2017, 72, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- El-Tahan, M.R.; Khidr, A.M.; Gaarour, I.S.; Alshadwi, S.A.; Alghamdi, T.A.; Al’ghamdi, A. A Comparison of 3 Videolaryngoscopes for Double-Lumen Tube Intubation in Humans by Users With Mixed Experience: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2018, 32, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamp, T.; Stumpner, T.; Grubhofer, G.; Ruetzler, K.; Thell, R.; Hager, H. Haemodynamic response at double lumen bronchial tube placement—Airtraq vs. MacIntosh laryngoscope, a randomised controlled trial. Heart Lung Vessel. 2015, 7, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heir, J.S.; Guo, S.-L.; Purugganan, R.; Jackson, T.A.; Sekhon, A.K.; Mirza, K.; Lasala, J.; Feng, L.; Cata, J.P. A Randomized Controlled Study of the Use of Video Double-Lumen Endobronchial Tubes Versus Double-Lumen Endobronchial Tubes in Thoracic Surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2018, 32, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.T.; Chou, S.H.; Wu, P.J.; Tseng, K.Y.; Kuo, Y.W.; Chou, C.Y.; Cheng, K.I. Comparison of the GlideScope videolaryngoscope and the Macintosh laryngoscope for double-lumen tube intubation. Anaesthesia 2012, 67, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.T.; Chou, S.H.; Chen, C.L.; Tseng, K.Y.; Kuo, Y.W.; Chen, M.K.; Cheng, K.I. Left endobronchial intubation with a double-lumen tube using direct laryngoscopy or the Trachway video stylet. Anaesthesia 2013, 68, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, P.; Zhou, R.; Lu, Z.; Hang, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, Z. GlideScope® versus C-MAC®(D) videolaryngoscope versus Macintosh laryngoscope for double lumen endotracheal intubation in patients with predicted normal airways: A randomized, controlled, prospective trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, H.; Komasawa, N.; Matsunami, S.; Kusaka, Y.; Minami, T. Comparison of McGRATH MAC and Macintosh laryngoscopes for double-lumen endotracheal tube intubation by anesthesia residents: A prospective randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Anesth. 2015, 27, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy-Faber, D.; Malyanker, Y.; Nir, R.-R.; Best, L.A.; Barak, M. Comparison of VivaSight double-lumen tube with a conventional double-lumen tube in adult patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Li, H.; Liu, W.; Cao, L.; Tan, H.; Zhong, Z. A randomised trial comparing the CEL-100 videolaryngoscope(TM) with the Macintosh laryngoscope blade for insertion of double-lumen tubes. Anaesthesia 2012, 67, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-H.; Dong, F.; Liu, J.-Y.; Wei, J.-Q.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Ma, W.-H. The use of ETView endotracheal tube for surveillance after tube positioning in patients undergoing lobectomy, randomized trial. Medicine 2018, 97, e13170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, A.; Chandy, J.; Punnoose, J.; Gnanamuthu, B.R.; Jeyseelan, L.; Sahajanandan, R. A randomized controlled study comparing CMAC video laryngoscope and Macintosh laryngoscope for insertion of double lumen tube in patients undergoing elective thoracotomy. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 37, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Onifade, A.; Lemon-Riggs, D.; Smith, A.; Pak, T.; Pruszynski, J.; Reznik, S.; Moon, T.S. Comparing the rate of fiberoptic bronchoscopy use with a video double lumen tube versus a conventional double lumen tube-a randomized controlled trial. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 6533–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risse, J.; Schubert, A.-K.; Wiesmann, T.; Huelshoff, A.; Stay, D.; Zentgraf, M.; Kirschbaum, A.; Wulf, H.; Feldmann, C.; Meggiolaro, K.M. Videolaryngoscopy versus direct laryngoscopy for double-lumen endotracheal tube intubation in thoracic surgery—A randomised controlled clinical trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020, 20, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, T.; Slinger, P.; Roscoe, A.; McRae, K.; Van Rensburg, A. A randomised controlled trial comparing the GlideScope() and the Macintosh laryngoscope for double-lumen endobronchial intubation. Anaesthesia 2013, 68, 1253–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuepbach, R.; Grande, B.; Camen, G.; Schmidt, A.R.; Fischer, H.; Sessler, D.I.; Seifert, B.; Spahn, D.R.; Ruetzler, K. Intubation with VivaSight or conventional left-sided double-lumen tubes: A randomized trial. Can. J. Anaesth. 2015, 62, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.B.; Bhargava, A.K.; Hariharan, U.; Mittal, A.K.; Goel, N.; Choudhary, M. A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing the Standard Mcintosh Laryngoscope and the C-Mac D blade Video laryngoscope™ for Double Lumen Tube Insertion for One Lung Ventilation in Onco surgical Patients. Indian J. Anaesth. 2016, 60, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasem, S.; Lazarus, M.; Hain, J.; Festl, J.; Kranke, P.; Roewer, N.; Lange, M.; Smul, T.M. Comparison of the Airtraq and the Macintosh laryngoscope for double-lumen tube intubation: A randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2013, 30, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Li, M.; Guo, X.Y. Comparison of Shikani optical stylet and Macintosh laryngoscope for double-lumen endotracheal tube intubation. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2015, 47, 853–857. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Kim, J.A.; Ahn, H.J.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, D.K.; Cho, E.A. Double-lumen tube tracheal intubation using a rigid video-stylet: A randomized controlled comparison with the Macintosh laryngoscope. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.L.; Wan, L.; Xu, H.; Qian, W.; Wang, X.R.; Tian, Y.K.; Zhang, C.H. A comparison of the McGrath® Series 5 videolaryngoscope and Macintosh laryngoscope for double-lumen tracheal tube placement in patients with a good glottic view at direct laryngoscopy. Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Huang, Y.; Luo, A. Comparison of GlideScope video-laryngoscope and Macintosh laryngoscope for double-lumen tube intubation. Chin. J. Anesthesiol. 2013, 33, 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Haam, S.J.; Kim, D.H. Comparison of the McGrath videolaryngoscope and the Macintosh laryngoscope for double lumen endobronchial tube intubation in patients with manual in-line stabilization: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2018, 97, e0081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.T.; Li, L.; Wan, L.; Zhang, C.H.; Yao, W.L. Video laryngoscopy vs. Macintosh laryngoscopy for double-lumen tube intubation in thoracic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 2018, 73, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Song, J.; Lim, B.G.; Lee, I.O.; Won, Y.J. Different classes of videoscopes and direct laryngoscopes for double-lumen tube intubation in thoracic surgery: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, W.L.; Zhang, C.H. Macintosh laryngoscopy for double-lumen tube placement—A reply. Anaesthesia 2015, 70, 1206–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- El-Boghdadly, K.; Bailey, C.R.; Wiles, M.D. Postoperative sore throat: A systematic review. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.Y.; Kim, J.; Oh, Y.J.; Lee, B.; Shin, Y.S.; Na, S. Risk factors for peri-anaesthetic dental injury. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).