Real-Life Experience with Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Genotypes 1 and 4 in Children Aged 12 to 17 Years—Results of the POLAC Project

Abstract

:1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Treatment Monitoring and Outcomes

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Study Group

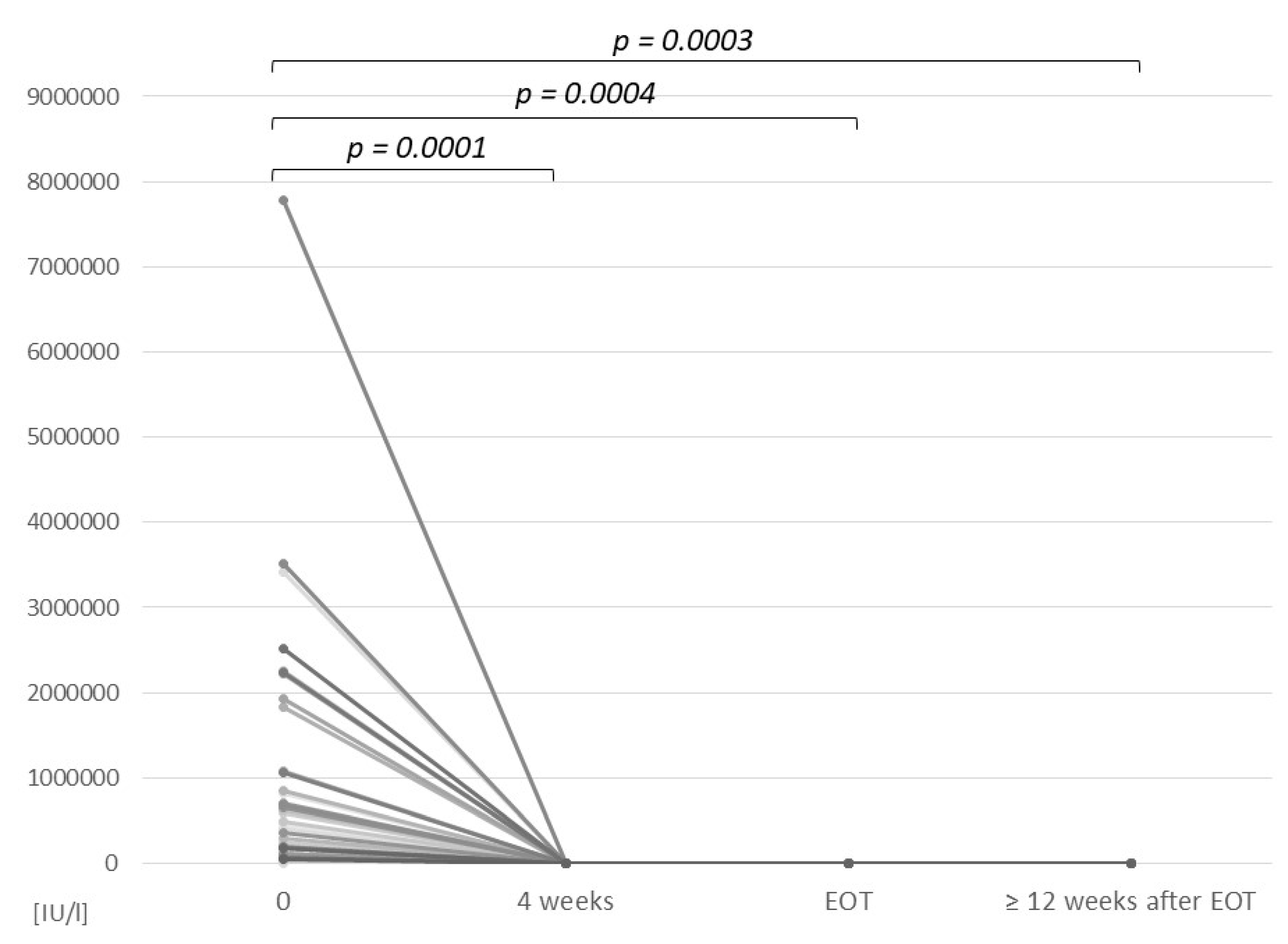

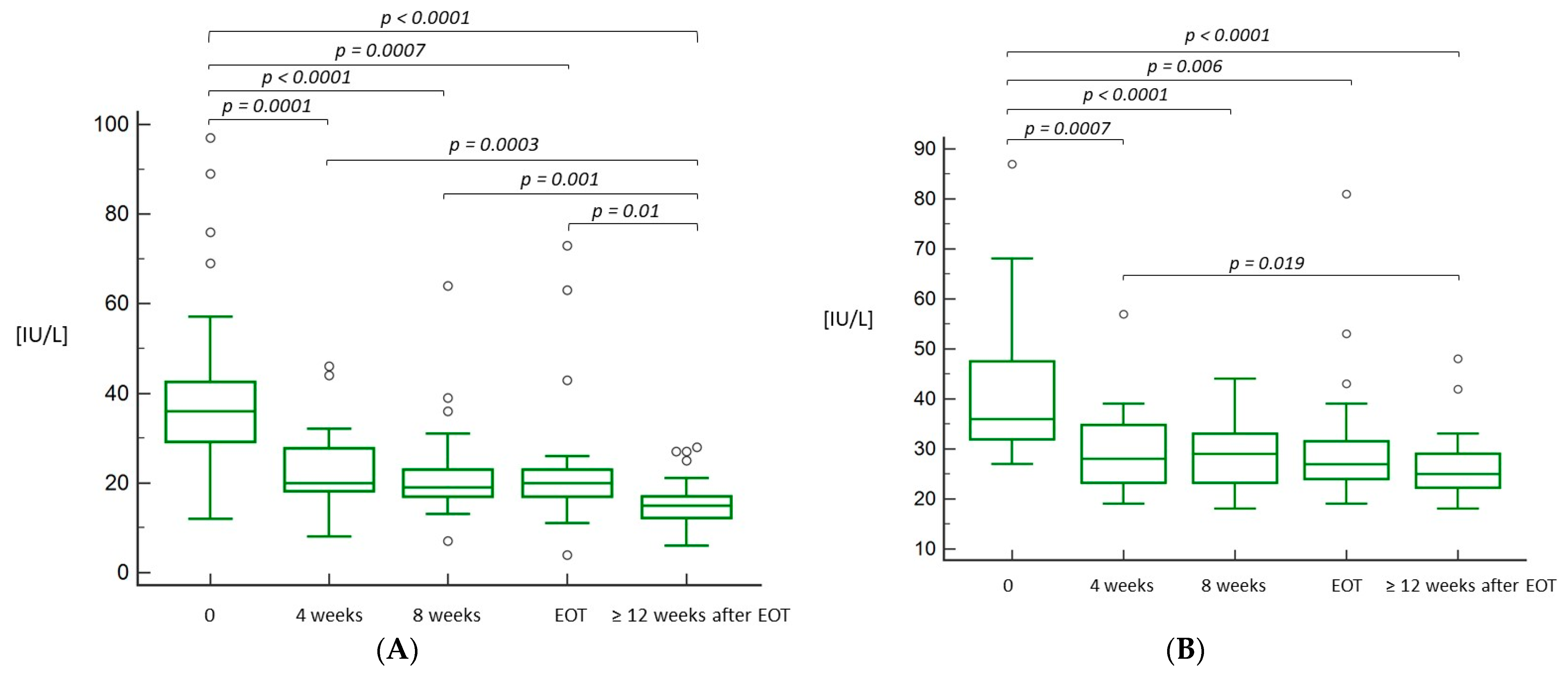

3.2. Efficacy of the Treatment

3.3. Tolerability and Safety of the Treatment

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schmelzer, J.; Dugan, E.; Blach, S.; Coleman, S.B.; Cai, Z.; DePaola, M.; Estes, C.; Gamkrelidze, I.; Jerabek, K.; Ma, S.; et al. Global prevalence of hepatitis C virus in children in 2018: A modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health. Reports on Cases of Infectious Diseases and Poisonings in Poland. Available online: http://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/index_a.html#01 (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Modin, L.; Arshad, A.; Wilkes, B.; Benselin, J.; Lloyd, C.; Irving, W.L.; Kelly, D.A. Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis C virus infection among children and young people. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokorska-Śpiewak, M.; Dobrzeniecka, A.; Lipińska, M.; Tomasik, A.; Aniszewska, M.; Marczyńska, M. Liver Fibrosis Evaluated With Transient Elastography in 35 Children With Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkova, A.; Volynets, G.V.; Crichton, S.; Skvortsova, T.A.; Panfilova, V.N.; Rogozina, N.V.; Khavkin, A.I.; Tumanova, E.L.; Indolfi, G.; Thorne, C. Advanced liver disease in Russian children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. J. Viral Hepat. 2019, 26, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Schwarz, K.B.; Wirth, S.; Rosenthal, P.; Gonzalez-Peralta, R.; Murray, K.; Henry, L.; Hunt, S. Quality of life in adolescents with hepatitis C treated with sofosbuvir and ribavirin. J. Viral Hepat. 2017, 25, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York, United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Balistreri, W.F.; Murray, K.F.; Rosenthal, P.; Bansal, S.; Lin, C.H.; Kersey, K.; Massetto, B.; Zhu, Y.; Kanwar, B.; German, P.; et al. The safety and effectiveness of ledipasvir-sofosbuvir in adolescents 12–17 years old with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Hepatology 2017, 66, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.F.; Balistreri, W.F.; Bansal, S.; Whitworth, S.; Evans, H.M.; Gonzalez-Peralta, R.P.; Wen, J.; Massetto, B.; Kersey, K.; Shao, J.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Ledipasvir-Sofosbuvir With or Without Ribavirin for Chronic Hepatitis C in Children Ages 6–11. Hepatology 2018, 68, 2158–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schwarz, K.B.; Rosenthal, P.; Murray, K.F.; Honegger, J.R.; Hardikar, W.; Hague, R.; Mittal, N.; Massetto, B.; Brainard, D.M.; Hsueh, C.; et al. Ledipasvir-Sofosbuvir for 12 Weeks in Children 3 to <6 Years Old With Chronic Hepatitis C. Hepatology 2019, 71, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, M.H.; Indolfi, G. Hepatitis C Virus Treatment in Children: A Challenge for Hepatitis C Virus Elimination. Semin. Liver Dis. 2020, 40, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indolfi, G.; Easterbrook, P.; Dusheiko, G.; El-Sayed, M.H.; Jonas, M.M.; Thorne, C.; Bulterys, M.; Siberry, G.; Walsh, N.; Chang, M.-H.; et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in children and adolescents. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indolfi, G.; Giometto, S.; Serranti, D.; Bettiol, A.; Bigagli, E.; De Masi, S.; Lucenteforte, E. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The efficacy and safety of direct-acting antivirals in children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 52, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rogers, M.E.; Balistreri, W.F. Cascade of care for children and adolescents with chronic hepatitis C. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indolfi, G.; Hierro, L.; Dezsofi, A.; Jahnel, J.; Debray, D.; Hadzic, N.; Czubowski, P.; Gupte, G.; Mozer-Glassberg, Y.; Van Der Woerd, W.; et al. Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Children: A Position Paper by the Hepatology Committee of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castéra, L.; Vergniol, J.; Foucher, J.; Le Bail, B.; Chanteloup, E.; Haaser, M.; Darriet, M.; Couzigou, P.; de Lédinghen, V. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behairy, B.E.; El-Araby, H.A.; El-Guindi, M.A.; Basiouny, H.M.; Fouad, O.A.; Ayoub, B.A.; Marei, A.M.; Sira, M.M. Safety and Efficacy of 8 Weeks Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir for Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype 4 in Children Aged 4–10 Years. J. Pediatr. 2020, 219, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Araby, H.A.; Behairy, B.E.; El-Guindi, M.A.; Adawy, N.M.; Allam, A.A.; Sira, A.M.; Khedr, M.A.; Elhenawy, I.A.; Sobhy, G.A.; Basiouny, H.E.D.M.; et al. Generic sofosbuvir/ledipasvir for the treatment of genotype 4 chronic hepatitis C in Egyptian children (9–12 years) and adolescents. Hepatol. Int. 2019, 13, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Karaksy, H.; Mogahed, E.A.; Abdullatif, H.; Ghobrial, C.; El-Raziky, M.S.; El-Koofy, N.; El-Shabrawi, M.; Ghita, H.; Baroudy, S.; Okasha, S. Sustained Viral Response in Genotype 4 Chronic Hepatitis C Virus-infected Children and Adolescents Treated With Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 67, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khayat, H.; Kamal, E.M.; Yakoot, M.; Gawad, M.A.; Kamal, N.; El Shabrawi, M.; El-Shabrawi, M.; Ghita, H.; Baroudy, S.; Okasha, S. Effectiveness of 8-week sofosbuvir/ledipasvir in the adolescent chronic hepatitis C-infected patients. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 31, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khayat, H.R.; Kamal, E.M.; El-Sayed, M.H.; El-Shabrawi, M.; Ayoub, H.; Rizk, A.; Maher, M.; El Sheemy, R.Y.; Fouad, Y.M.; Attia, D. The effectiveness and safety of ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir in adolescents with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4 infection: A real-world experience. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Shabrawi, M.; Kamal, N.M.; El-Khayat, H.R.; Kamal, E.M.; AbdelGawad, M.M.A.H.; Yakoot, M. A pilot single arm observational study of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (200 + 45 mg) in 6- to 12- year old children. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 47, 1699–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, E.M.; El-Shabrawi, M.; El-Khayat, H.; Yakoot, M.; Sameh, Y.; Fouad, Y.; Attia, D. Effects of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir therapy on chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 4, infected children of 3-6 years of age. Liver Int. 2019, 40, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serranti, D.; Nebbia, G.; Cananzi, M.; Nicastro, E.; Di Dato, F.; Nuti, F.; Garazzino, S.; Silvestro, E.; Giacomet, V.; Forlanini, F.; et al. Efficacy of Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir in Adolescents With Chronic Hepatitis C Genotypes 1, 3, and 4: A Real-world Study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 72, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokorska-Śpiewak, M.; Dobrzeniecka, A.; Ołdakowska, A.; Marczyńska, M. Effective Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir in 2 Teenagers with HIV Coinfection: A Brief Report. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewicz, J.; Pawłowska, M.; Simon, K.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Lorenc, B.; Klapaczyński, J.; Tudrujek-Zdunek, M.; Sitko, M.; Mazur, W.; Janczewska, E.; et al. Low risk of HBV reactivation in a large European cohort of HCV/HBV coinfected patients treated with DAA. Expert Rev. Anti-Infective Ther. 2020, 18, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, H.M.; Sabry, M.A.; Ahmed, A.; Hassany, M.; Al Soda, M.F.; Aziz, H.A. Generic Ledipasvir-Sofosbuvir Treatment for Adolescents With Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2019, 9, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serranti, D.; Dodi, I.; Nicastro, E.; Cangelosi, A.M.; Riva, S.; Ricci, S.; Bartolini, E.; Trapani, S.; Mastrangelo, G.; Vajro, P.; et al. Shortened 8-Week Course of Sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir Therapy in Adolescents With Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 69, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhlouf, N.A.; Abdelmalek, M.O.; Ibrahim, M.E.; Abu-Faddan, N.H.; Kheila, A.E.; Mahmoud, A.A. Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir in Adolescents With Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype 4 With and Without Hematological Disorders: Virological Efficacy and Impact on Liver Stiffness. J. Pediatric. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2021, 10, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, H.M.; Ahmed Mohamed, A.; Sabry, M.; Abdel Aziz, H.; Eysa, B.; Rabea, M. The Effectiveness of Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir in Youth With Genotype 4 Hepatitis C Virus: A Single Egyptian Center Study. Pediatr Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokorska-Śpiewak, M.; Śpiewak, M. Management of hepatitis C in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. World J. Hepatol. 2020, 12, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Number (%) or Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 23 (62) |

| Female | 14 (38) | |

| Age | Median (IQR) | 15 (12; 16) |

| HCV genotype | 1 | 32 (86) |

| 4 | 5 (14) | |

| Mode of infection | Mother-to-child transmission | 30 (81) |

| Unknown | 7 (19) | |

| Previous ineffective treatment with interferon plus ribavirin | Yes | 14 (38) |

| No | 23 (62) | |

| BMI | Median (IQR) | 20.4 (17.7; 22.5) |

| BMI z-score | Median (IQR) | 0.23 (−0.65; 0.83) |

| ALT | IU/mL, median (IQR) | 37 (30; 48) |

| AST | IU/mL, median (IQR) | 36 (32; 48) |

| HCV viral load | IU/mL, median (IQR) | 5.83 × 105 (1.8 × 105; 12.6 × 105) |

| Liver fibrosis (LSM corresponding to METAVIR scale) | F0/F1 | 33 (89) |

| F2 | 1 (3) | |

| F3 | 0 | |

| F4 | 3 (8) | |

| Anti-HIV | Positive | 2 (5) |

| Anti-HBc total | Positive | 1 (3) |

| Duration of LDV/SOF treatment | 12 weeks | 35 (95) |

| 24 weeks | 2 (5) | |

| Patient Characteristics | Number | SVR12 (ITT) | SVR12 (PP) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 36/37 | 97% | 100% | |

| HCV genotype | 1 | 31/32 | 97% | 100% |

| 4 | 5/5 | 100% | 100% | |

| Baseline liver fibrosis (METAVIR) | F0/1 | 33/33 | 100% | 100% |

| F ≥ 2 | 3/4 | 75% | 100% | |

| Duration of LDV/SOF treatment | 12 weeks | 35/35 | 100% | 100% |

| 24 weeks | 1/2 | 50% | 100% | |

| Previous ineffective treatment with interferon and ribavirin | Yes | 13/14 | 93% | 100% |

| No | 23/23 | 100% | 100% | |

| Symptom | Frequency, Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Any | 11 (30) |

| Fatigue | 5 (14) |

| Headache | 4 (11) |

| Sleepiness | 2 (5) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (5) |

| No | Patients Age Range (Years) | Number of Participants | HCV Genotype | Duration of Treatment (Weeks) | Number of Patients Achieving SVR12 (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12–18 | 40 | 4 | 12 | 100 | El-Karaksy et al., 2018 [19] |

| 2 | 12–18 | 46 | NA | 12 | 98 | Fouad et al., 2020 [27] |

| 3 | 12–17 | 100 | 1 | 12 | 98 | Balistreri et al., 2017 [8] |

| 4 | 12–17 | 144 | 4 | 12 | 99 | El-Khayat et al., 2018 [21] |

| 5 | 12–17 | 14 | 1 | 8 | 100 | Serranti et al., 2019 [28] |

| 6 | 12–17 | 78 | 1, 3, 4 | 8, 12 or 24 | 97.4 | Serranti et al., 2021 [24] |

| 7 | 12–17 | 157 | 4 | 8 or 12 | 98 | El-Khayat et al., 2019 [20] |

| 8 | 12–17 | 65 | 4 | 12 | 100 | Makhlouf et al., 2021 [29] |

| 9 | 11–17 | 51 | 4 | 12 | 100 | Fouad et al., 2019 [30] |

| 10 | 9–12 | 100 | 4 | 12 | 100 | El-Araby et al., 2019 [18] |

| 11 | 6–12 | 20 | 4 | 12 | 95 | El-Shabrawi et al., 2018 [22] |

| 12 | 6–11 | 92 | 1, 3, 4 | 12 or 24 | 99 | Murray et al., 2018 [9] |

| 13 | 4–10 | 30 | 4 | 8 | 100 | Behairy et al., 2020 [17] |

| 14 | 3–6 | 22 | 4 | 8 or 12 | 100 | Kamal et al., 2020 [23] |

| 15 | 3–5 | 34 | 1, 4 | 12 | 97 | Schwarz et al., 2020 [10] |

| Overall and According to the HCV Genotype | ||||||

| 16 | 3–18 | 1016 | 1, 3, 4 | 8, 12 or 24 | 98.6 | * |

| 17 | 3–17 | 317 | 1 | 8, 12 or 24 | 98.4 | ** |

| 18 | 6–17 | 4 | 3 | 24 | 75 | *** |

| 19 | 3–18 | 649 | 4 | 8 or 12 | 98.9 | **** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pokorska-Śpiewak, M.; Dobrzeniecka, A.; Aniszewska, M.; Marczyńska, M. Real-Life Experience with Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Genotypes 1 and 4 in Children Aged 12 to 17 Years—Results of the POLAC Project. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184176

Pokorska-Śpiewak M, Dobrzeniecka A, Aniszewska M, Marczyńska M. Real-Life Experience with Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Genotypes 1 and 4 in Children Aged 12 to 17 Years—Results of the POLAC Project. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(18):4176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184176

Chicago/Turabian StylePokorska-Śpiewak, Maria, Anna Dobrzeniecka, Małgorzata Aniszewska, and Magdalena Marczyńska. 2021. "Real-Life Experience with Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Genotypes 1 and 4 in Children Aged 12 to 17 Years—Results of the POLAC Project" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 18: 4176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184176

APA StylePokorska-Śpiewak, M., Dobrzeniecka, A., Aniszewska, M., & Marczyńska, M. (2021). Real-Life Experience with Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Genotypes 1 and 4 in Children Aged 12 to 17 Years—Results of the POLAC Project. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(18), 4176. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184176