Prevalence of Chronic Heart Failure, Associated Factors, and Therapeutic Management in Primary Care Patients in Spain, IBERICAN Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study

2.2. Data on Patients

2.3. Data on the Evaluation of Heart Failure

2.4. Data on Drug Treatment

2.5. Control of the Main Cardiovascular Risk Factors

2.6. Quality of Data

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample

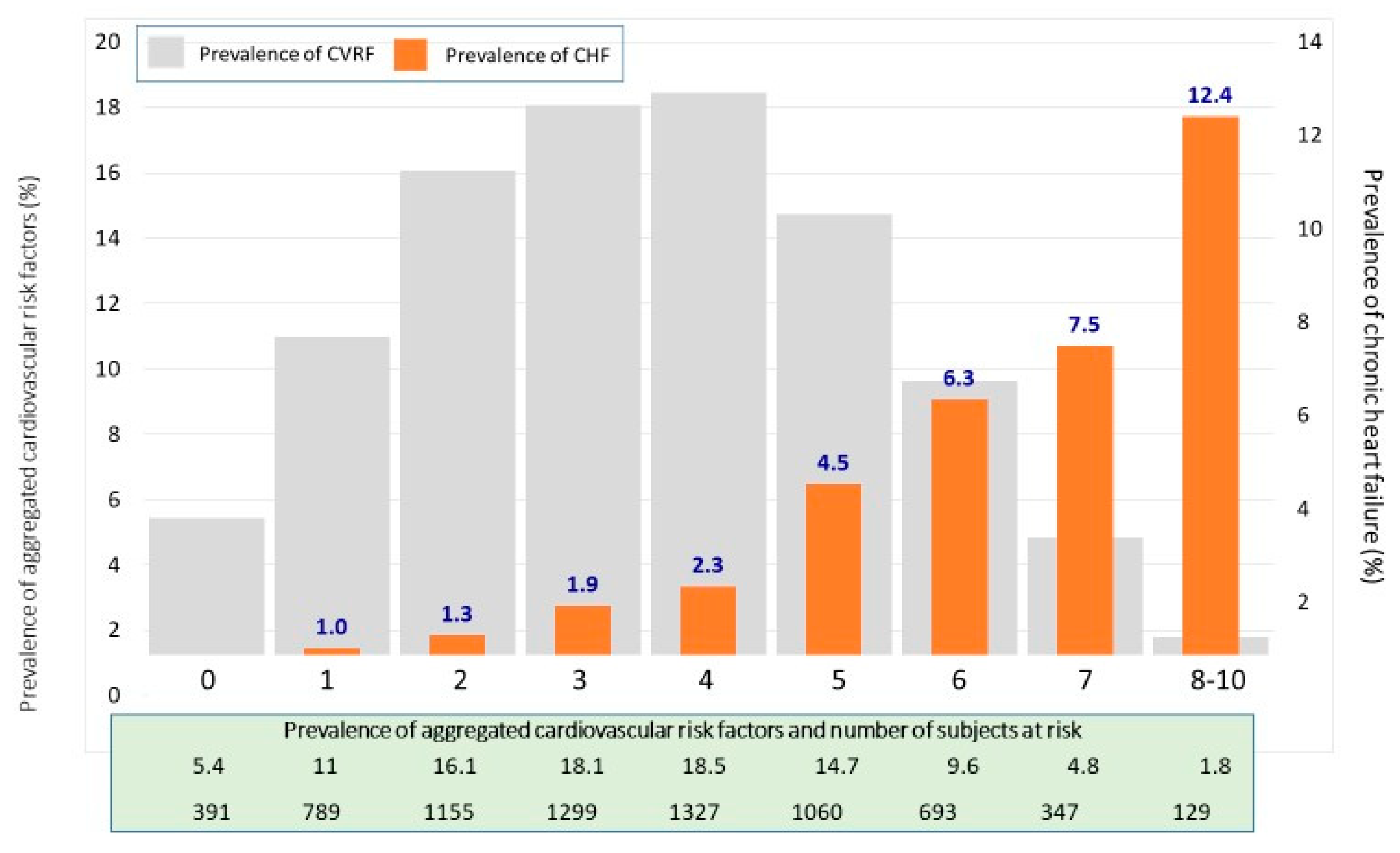

3.2. Prevalence of Chronic Heart Failure

3.3. Control of Main Cardiovascular Risk Factors

3.4. Drug Treatment for CHF

3.5. Variables Associated with Chronic Heart Failure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Investigators

Scientific Committee

Andalucía

Aragón

Cantabria

Castilla La Mancha

Castilla y León

Cataluña

Comunidad de Madrid

Comunidad Valenciana

Extremadura

Galicia

Illes Balears

Islas Canarias

La Rioja

Melilla

País Vasco

Principado de Asturias

Región de Murcia

References

- Cleland, J.G.F.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Ponikowski, P. The year in cardiology 2018: Heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita, M.; Crespo, M.G.; de Teresa, E.; Jiménez, M.; Alonso-Pulpón, L.; Muñiz, J. Study investigators. Prevalence of heart failure in the Spanish general population aged over 45 years. The PRICE Study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2008, 61, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Juanatey, J.R.; Alegría, E.; Bertomeu, V.; Conthe, P.; Santiago, A.; Zsolt, I. Heart failure in outpatients: Comorbidities and management by different specialists. The EPISERVE Study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2008, 1, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Ravina, F.; Grigorian-Shamagian, L.; Fransi-Galiana, L.; Nazara-Otero, C.; Fernandez-Villaverde, J.M.; del Alamo-Alonso, A.; Nieto-Pol, E.; de Santiago-Boullón, M.; López-Rodríguez, I.; Cardona-Vidal, J.M.; et al. Galician study of heart failure in primary care (GALICAP Study). Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2007, 60, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Roca, G.C.; Barrios Alonso, V.; Aznar Costa, J.; Llisterri Caro, J.L.; Alonso Moreno, F.J.; Escobar Cervantes, C.; Lou Arnal, S.; Divisón Garrote, J.A.; Murga Eizagaechevarría, N.; Matalí Gilarranz, A.; et al. Clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed of chronic heart failure attended in primary care. The CARDIOPRES study. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2007, 207, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita Sánchez, M. The research group of the BADAPIC Registry. Clinical characteristics, treatment and short-term morbidity and mortality of patients with heart failure followed in heart failure clinics. Results of the BADAPIC Registry. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2004, 57, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the heart failure association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Yusuf, S. Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. JAMA 1995, 273, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Shibata, M.C.; Wedel, H.; Böhm, M.; Flather, M.D. On behalf of the Beta-blockers in heart failure collaborative group. effect of age and sex on efficacy and tolerability of β blockers in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Individual patient data meta-analysis. BMJ 2016, 353, i1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, C.; Parellada, N.; Alvarado, C.; Moll, D.; Muñoz, M.D.; Romero, C. Heart failure: A view from primary care. Aten. Primaria 2010, 42, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruiz-Romero, V.; Lorusso, N.; Expósito Páez-Pinto, J.M.; Palmero-Palmero, C.; Caballero-Delgado, G.; Zapico Moreno, M.J.; Fernández-Moyano, A. Avoidable hospital admissions for heart failure, Spain. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2016, 90, e1–e11. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1135-57272016000100408&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=en (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Cinza Sanjurjo, S.; Llisterri Caro, J.L.; Barquilla García, A.; Polo García, J.; Velilla Zancada, S.; Rodríguez Roca, G.C.; Micó Pérez, R.M.; Martín Sánchez, V.; Prieto Díaz, M.Á.; en Representación de los Investigadores del Estudio IBERICAN. Description of the sample, design and methods of the study for the identification of the Spanish population at cardiovascular and renal risk (IBERICAN). Semergen 2020, 46, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancia, G.; Fagard, R.; Narkiewicz, K.; Redon, J.; Zanchetti, A.; Böhm, M.; Christiaens, T.; Cifkova, R.; De Backer, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2159–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2018. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G.; Machin, D.; Bryant, T.N.; Gardner, M.J. (Eds.) Statistics with Confidence, 2nd ed.; BMJ Books: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios Alonso, V.; Peña Pérez, G.; González Juanatey, J.R.; Alegría Ezquerra, E.; Lozano Vidal, J.V.; Llisterri Caro, J.L.; González Maqueda, I. Hypertension and heart failure in primary care and cardiology consultations of in Spain. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2003, 203, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadó-Hernández, C.; Cosculluela-Torres, P.; Blanes-Monllor, C.; Parellada-Esquius, N.; Méndez-Galeano, C.; Maroto-Villanova, N.; García-Cerdán, R.M.; Núñez-Manrique, M.P.; Barrio-Ruiz, C.; Salvador-González, B.; et al. Heart failure in primary care: Attitudes, knowledge and self-care. Aten. Primaria 2018, 50, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rivas, B.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; Brotons, C.; Aznar, J.; Sobreviela, E. Clinical profile and management patterns in outpatients with heart failure in Spain: INCA study. Aten. Primaria 2009, 41, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, B.; Lupón, J.; Parajón, T.; Urrutia, A.; Herreros, J.; Valle, V. Use of the European heart failure self-care behaviour scale (EHFScBS) in a heart failure unit in Spain. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2006, 59, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortina, A.; Reguero, J.; Segovia, E.; Rodríguez Lambert, J.L.; Cortina, R.; Arias, J.C.; Vara, J.; Torre, F. Prevalence of heart failure in Asturias (A region in the north of Spain). Am. J. Cardiol. 2001, 87, 1417–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré, N.; Vela, E.; Clèries, M.; Bustins, M.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Enjuanes, C.; Moliner, P.; Ruiz, S.; Verdú-Rotellar, J.M.; Comín-Colet, J. Medical resource use and expenditure in patients with chronic heart failure: A population-based analysis of 88,195 patients. Eur. J. Heart Fail 2016, 18, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, M.; García-Olmos, L.M.; Alberquilla, A.; Muñoz, A.; García-Sagredo, P.; Somolinos, R.; Pascual-Carrasco, M.; Salvador, C.H.; Monteagudo, J.L. Heart failure in the family practice: A study of the prevalence and co-morbidity. Fam. Pract. 2011, 28, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Quach, S.; Blais, C.; Quan, H. Administrative data have high variation in validity for recording heart failure. Can. J. Cardiol. 2010, 26, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauw, W.J.C.; Schalk, B.W.M.; Biermans, M.C.J. Heart failure in primary care: Prevalence related to age and comorbidity. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2019, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceia, F.; Fonseca, C.; Mota, T.; Morais, H.; Matias, F.; de Sousa, A.; Oliveira, A. EPICA investigators.prevalence of chronic heart failure in southwestern Europe: The EPICA study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2002, 4, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayago-Silva, I.; García-López, F.; Segovia-Cubero, J. Epidemiology of heart failure in Spain over the last 20 years. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2013, 66, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiller, D.; Russ, M.; Greiser, K.H.; Nuding, S.; Ebelt, H.; Kluttig, A.; Kors, J.A.; Thiery, J.; Bruegel, M.; Haerting, J.; et al. Prevalence of symptomatic heart failure with reduced and with normal ejection fraction in an elderly general population—The Carla study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, G.; Esteve, I.C.; Gatius, J.R.; Santiago, L.G.; Lacruz, C.M.; Soler, P.S. Heart failure patients in primary care: Aging, comorbidities and polypharmacy. Aten. Primaria 2011, 43, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McKee, P.A.; Castelli, W.P.; McNamara, P.M.; Kannel, W.B. The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham study. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llisterri, J.L.; Barrios, V.; de la Sierra, A.; Bertomeu, V.; Escobar, C.; González-Segura, D. Blood pressure control in hypertensive women aged 65 years or older in a primary care setting. MERICAP study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2011, 64, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Calvo, J.I.; Morales-Rull, J.L.; Amores-Ferreras, B.; Bueno-Gómez, J. Renal dysfunction and cardiac failure. An association that remains to be described. Dial. Traspl. 2007, 28, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, W.S.; Clare, R.; Ellis, S.J.; Mills, J.S.; Fischman, D.L.; Kraus, W.E.; Whellan, D.J.; O’Connor, C.M.; Patel, M.R. Effect of peripheral arterial disease on functional and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure (from H-ACTION). Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frigola-Capell, E.; Verdú-Rotellar, J.M.; Comin-Colet, J.; Davins-Miralles, J.; Hermosilla, E.; Wensing, M.; Suñol, R. Prescription in patients with chronic heart failure and multimorbidity attended in primary care. Qual. Prim. Care 2013, 21, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Anguita, M.; Comín, J.; Formiga, F.; Almenar, L.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Manzano, L. Investigators of the VIDA–IC study. Current situation of management of systolic heart failure in Spain: VIDA-IC study results. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2014, 67, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Segovia-Cubero, J.; González-Costello, J. Adherence to the ESC heart failure treatment guidelines in Spain: ESC heart failure long-term registry. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2015, 68, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farré, N.; Vela, E.; Clèries, M.; Bustins, M.; Cainzos-Achirica, M.; Enjuanes, C.; Moliner, P.; Ruiz, S.; Verdú-Rotellar, J.M.; Comín-Colet, J. Real world heart failure epidemiology and outcome: A population-based analysis of 88, 195 patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R.; Rouleau, J.L.; Shi, V.C.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; et al. PARADIGM-HF investigators and committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

All

| 249 | 3.1 | 2.31–3.76 | |

| 20 | 0.9 | 0.52–1.31 | <0.001 | |

| 43 | 1.6 | 1.14–2.11 | ||

| 120 | 4.7 | 3.93–5.62 | ||

| 66 | 15.2 | 11.98–18.93 | ||

Men (all)

| 117 | 3.2 | 2.64–3.81 | |

| 9 | 0.9 | 0.42–1.74 | <0.001 | |

| 20 | 1.6 | 0.95–2.39 | ||

| 60 | 5.0 | 3.86–6.42 | ||

| 28 | 13.1 | 8.91–18.35 | ||

Women (all)

| 132 | 3.0 | 2.51–3.54 | |

| 11 | 0.8 | 0.40–1.42 | <0.001 | |

| 23 | 1.6 | 1.00–2.36 | ||

| 60 | 4.5 | 3.41–5.68 | ||

| 38 | 17.3 | 12.52–22.82 |

| Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFR_CKD_EPI (continuous per unit) | 0.988 | 0.978–0.998 | 0.014 |

| Triglycerides (continuous per unit) | 1.003 | 1.001–1.004 | 0.005 |

| BMI (continuous per unit) | 1.028 | 1.007–1.050 | 0.009 |

| Age (continuous per year) | 1.034 | 1.012–1.057 | 0.002 |

| Arterial hypertension (yes vs. no) | 1.421 | 1.196–1.688 | <0.001 |

| Personal history of PVD (yes vs. no) | 2.029 | 1.206–3.414 | <0.001 |

| Personal history of AF (yes vs. no) | 3.494 | 2.018–6.049 | <0.001 |

| TOD_LVH (yes vs. no) | 5.968 | 3.960–8.994 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llisterri-Caro, J.L.; Cinza-Sanjurjo, S.; Martín-Sánchez, V.; Rodríguez-Roca, G.C.; Micó-Pérez, R.M.; Segura-Fragoso, A.; Velilla-Zancada, S.; Polo-García, J.; Barquilla-García, A.; Rodríguez Padial, L.; et al. Prevalence of Chronic Heart Failure, Associated Factors, and Therapeutic Management in Primary Care Patients in Spain, IBERICAN Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184036

Llisterri-Caro JL, Cinza-Sanjurjo S, Martín-Sánchez V, Rodríguez-Roca GC, Micó-Pérez RM, Segura-Fragoso A, Velilla-Zancada S, Polo-García J, Barquilla-García A, Rodríguez Padial L, et al. Prevalence of Chronic Heart Failure, Associated Factors, and Therapeutic Management in Primary Care Patients in Spain, IBERICAN Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(18):4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184036

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlisterri-Caro, Jose L., Sergio Cinza-Sanjurjo, Vicente Martín-Sánchez, Gustavo C. Rodríguez-Roca, Rafael M. Micó-Pérez, Antonio Segura-Fragoso, Sonsoles Velilla-Zancada, Jose Polo-García, Alfonso Barquilla-García, Luis Rodríguez Padial, and et al. 2021. "Prevalence of Chronic Heart Failure, Associated Factors, and Therapeutic Management in Primary Care Patients in Spain, IBERICAN Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 18: 4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184036

APA StyleLlisterri-Caro, J. L., Cinza-Sanjurjo, S., Martín-Sánchez, V., Rodríguez-Roca, G. C., Micó-Pérez, R. M., Segura-Fragoso, A., Velilla-Zancada, S., Polo-García, J., Barquilla-García, A., Rodríguez Padial, L., Prieto-Díaz, M. A., & on behalf of the Investigators of the IBERICAN Study and of the Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians (SEMERGEN)’s Foundation. (2021). Prevalence of Chronic Heart Failure, Associated Factors, and Therapeutic Management in Primary Care Patients in Spain, IBERICAN Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(18), 4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184036