Fetal Cardiac Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Does It Affect Parental Counseling?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Der Linde, D.; Konings, E.E.; Slager, M.A.; Witsenburg, M.; Helbing, W.A.; Takkenberg, J.J.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gardiner, H.M.; Kovacevic, A.; van der Heijden, L.B.; Pfeiffer, P.W.; Franklin, R.C.; Gibbs, J.L.; Averiss, I.E.; LaRovere, J.M. Prenatal screening for major congenital heart disease: Assessing per-formance by combining national cardiac audit with maternity data. Heart 2014, 100, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, L.D.; Huggon, I.C. Counselling following a diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Prenat. Diagn. 2004, 24, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donofrio, M.T.; Moon-Grady, A.J.; Hornberger, L.K.; Copel, J.A.; Sklansky, M.S.; Abuhamad, A.; Cuneo, B.F.; Huhta, J.C.; Jonas, R.A.; Krishnan, A.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014, 129, 2183–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, L.; Dangel, J.; Fesslova, V.; Marek, J.; Mellander, M.; Oberhänsli, I.; Oberhoffer, R.; Sharland, G.; Simpson, J.; Sonesson, S.-E. Recommendations for the practice of fetal cardiology in Europe. Cardiol. Young 2004, 14, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rychik, J.; Donaghue, D.D.; Levy, S.; Fajardo, C.; Combs, J.; Zhang, X.; Szwast, A.; Diamond, G.S. Maternal Psychological Stress after Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease. J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 302–307.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.; Diego, M.; Hernandez-Reif, M.; Schanberg, S.; Kuhn, C.; Yando, R.; Bendell, D. Pregnancy anxiety and comorbid depression and anger: Effects on the fetus and neonate. Depression Anxiety 2003, 17, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, T. Prenatal depression effects on early development: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2011, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, E.; de Medina, P.R.; Huizink, A.; Bergh, B.R.V.D.; Buitelaar, J.; Visser, G. Prenatal maternal stress: Effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child. Early Hum. Dev. 2002, 70, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, M. The potential influence of maternal stress hormones on development and mental health of the offspring. Brain Behav. Immun. 2005, 19, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talge, N.M.; Neal, C.; Glover, V. Early Stress, Translational Research and Prevention Science Network: Fetal and neonatal expe-rience on child and adolescent mental health. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: How and why? J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizink, A.C.; De Medina, P.G.R.; Mulder, E.; Visser, G.H.; Buitelaar, J.K. Stress during pregnancy is associated with developmental outcome in infancy. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2003, 44, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacevic, A.; Simmelbauer, A.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; Sohn, C.; Müller, A.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Assessment of Needs for Counseling After Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Disease—A Multidisciplinary Approach. Klin. Pädiatr. 2018, 230, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacevic, A.; Simmelbauer, A.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; Müller, A.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Counseling for Prenatal Congenital Heart Disease—Recommendations Based on Empirical Assessment of Counseling Success. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kovacevic, A.; Bär, S.; Starystach, S.; Simmelbauer, A.; Elsässer, M.; Müller, A.; Motlagh, A.M.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ostermayer, E.; Ewert, P.; et al. Objective Assessment of Counselling for Fetal Heart Defects: An Interdisciplinary Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kovacevic, A.; Elsässer, M.; Fluhr, H.; Müller, A.; Starystach, S.; Bär, S.; Gorenflo, M. Counseling for fetal heart disease—Current standards and best practice. Transl. Pediatr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.B.; Mainali, A.; Schwank, S.E.; Acharya, G. Maternal mental health in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotabagi, P.; Fortune, L.; Essien, S.; Nauta, M.; Yoong, W. Anxiety and depression levels among pregnant women with COVID-19. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2020, 99, 953–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Guo, J.; Fan, C.; Juan, J.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Feng, L.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Qiao, Y.; et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnant women: A report based on 116 cases. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 223, 111.e1–111.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, L.D.; Ellington, S.; Strid, P.; Galang, R.R.; Oduyebo, T.; Tong, V.T.; Woodworth, K.R.; Nahabedian, J.F., III; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Gilboa, S.M.; et al. Update: Characteristics of Symptomatic Women of Reproductive Age with Labora-tory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status—United States, 22 January–3 October 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1641–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahoy, M.J.; Whitaker, M.; O’Halloran, A.; Chai, S.J.; Kirley, P.D.; Alden, N.; Kawasaki, B.; Meek, J.; Yousey-Hindes, K.; Anderson, E.J.; et al. Characteristics and Maternal and Birth Outcomes of Hospitalized Pregnant Women with Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19—COVID-NET, 13 States, 1 March–22 August 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenizia, C.; Biasin, M.; Cetin, I.; Vergani, P.; Mileto, D.; Spinillo, A.; Gismondo, M.R.; Perotti, F.; Callegari, C.; Mancon, A.; et al. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 vertical transmission during pregnancy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, J.; Gil, M.M.; Rong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Poon, L.C. Effect of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on maternal, perinatal and neonatal outcome: Systematic review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020, 56, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.; Best, H. (Eds.) Handbuch der sozialwissenschaftlichen Datenanalyse; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, N.; Emeruwa, U.N.; Friedman, A.M.; Aubey, J.J.; Aziz, A.; Baptiste, C.D.; Coletta, J.M.; D’Alton, M.E.; Fuchs, K.M.; Goffman, D.; et al. Telehealth Uptake into Prenatal Care and Provider Attitudes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in New York City: A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis. Am. J. Perinatol. 2020, 37, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, B.N.; Klein, J.H.; Barbosa, M.B.; Hamersley, S.L.; Hickey, K.W.; Ahmadzia, H.K.; Broth, R.E.; Pinckert, T.L.; Sable, C.A.; Donofrio, M.T.; et al. Expanding Access to Fetal Telecardiology During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Telemed. e-Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evanoff, B.A.; Strickland, J.R.; Dale, A.M.; Hayibor, L.; Page, E.; Duncan, J.G.; Kannampallil, T.; Gray, D.L. Work-Related and Personal Factors Associated with Mental Well-Being during the COVID-19 Response: Survey of Health Care and Other Workers. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21366, Erratum in 2021, 23, e29069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Counseling Success | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | ||

| n = 198 | 147 | 51 | |

| Mean rank | p (Mann–Whitney-U) | ||

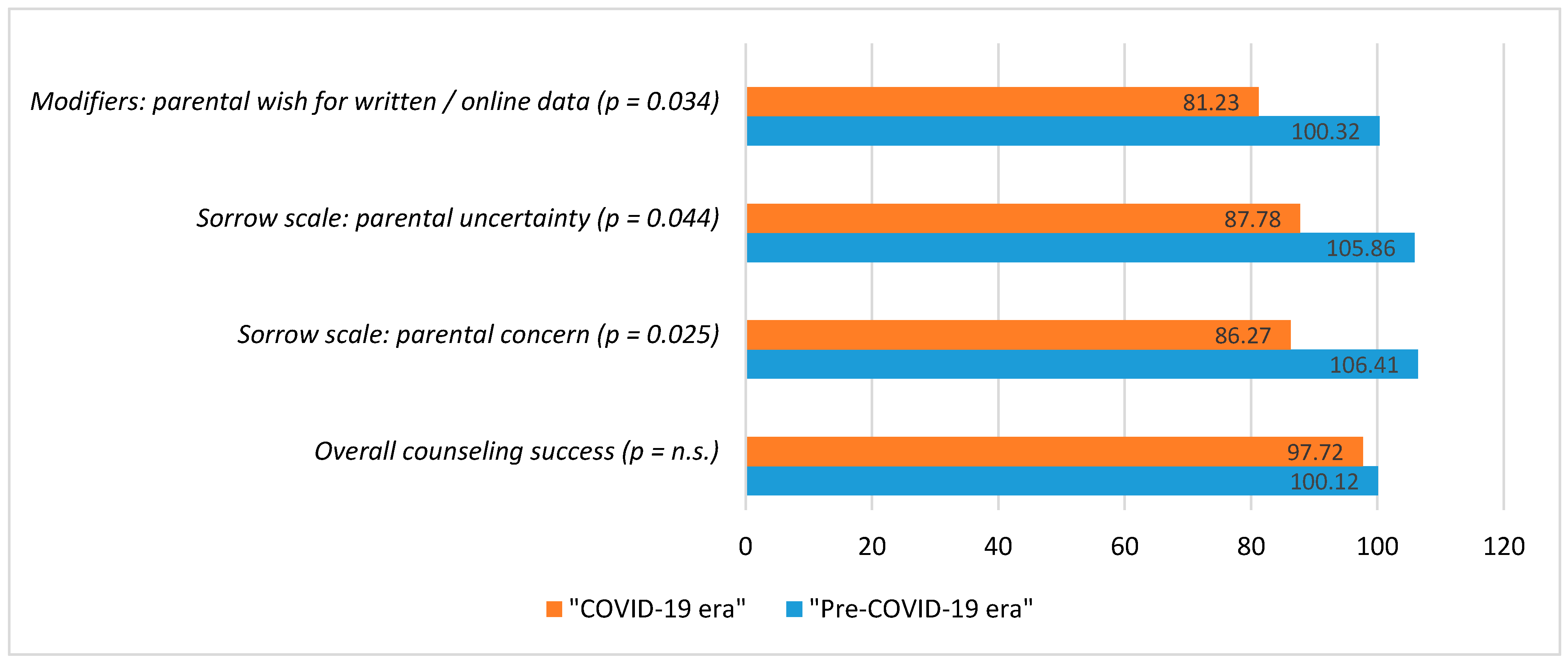

| (a) Overall counseling success | 100.12 | 97.72 | 0.766 |

| (b) Dimensions: | |||

| Transfer of medical knowledge | 100.58 | 96.38 | 0.605 |

| Trust in medical staff | 101.16 | 94.72 | 0.366 |

| Transparency regarding the treatment process | 99.32 | 100.01 | 0.930 |

| Coping resources | 99.99 | 98.10 | 0.818 |

| Perceived situational control | 100.29 | 97.23 | 0.721 |

| Sorrows | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | ||

| n = 201 | 147 | 54 | |

| Mean rank | p (Mann–Whitney-U) | ||

| I am very concerned. | 106.41 | 86.27 | 0.025 |

| I am unsure how to evaluate the situation. | 105.86 | 87.78 | 0.044 |

| I believe the situation must be taken seriously. | 104.86 | 90.48 | 0.108 |

| Modifiers of Counseling Success | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | ||

| n = 222 | 166 | 56 | |

| Mean rank | p * | ||

| Interruptions during counseling. | 107.97 | 121.96 | 0.116 |

| n = 222 | 167 | 55 | |

| Mean rank | p * | ||

| I would have preferred a separate counseling room. | 111.09 | 112.74 | 0.863 |

| n = 219 | 166 | 53 | |

| Mean rank | p * | ||

| Little time was lost after suspecting CHD in the fetus, making the diagnosis and counseling by a specialist. | 109.99 | 110.00 | 0.999 |

| n = 190 | 142 | 48 | |

| Mean rank | p * | ||

| I would have wished more detailed written explanatory information or links to useful online data. | 100.32 | 81.23 | 0.034 |

| Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Values | Mean Values | |

| (a) Overall counseling success | 1.58 | 1.70 |

| (b) Dimensions: | ||

| Transfer of medical knowledge | 1.55 | 1.50 |

| Trust in medical staff | 1.33 | 1.39 |

| Transparency regarding the treatment process | 1.38 | 1.35 |

| Coping resources | 1.60 | 1.73 |

| Perceived situational control | 1.75 | 1.62 |

| Counseling Success | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Successful | Satisfying | Unsuccessful | |

| (a) Overall counseling success | 57.1% | 42.9% | - |

| (b) Dimensions: | |||

| Transfer of medical knowledge | 100% | - | - |

| Trust in medical staff | 71.4% | 28.6% | - |

| Transparency regarding the treatment process | 100% | - | - |

| Coping resources | 62.5% | 37.5% | - |

| Perceived situational control | 75.0% | 12.5% | 12.5% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kovacevic, A.; Bär, S.; Starystach, S.; Elsässer, M.; van der Locht, T.; Mohammadi Motlagh, A.; Ostermayer, E.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Ewert, P.; Gorenflo, M.; et al. Fetal Cardiac Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Does It Affect Parental Counseling? J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153423

Kovacevic A, Bär S, Starystach S, Elsässer M, van der Locht T, Mohammadi Motlagh A, Ostermayer E, Oberhoffer-Fritz R, Ewert P, Gorenflo M, et al. Fetal Cardiac Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Does It Affect Parental Counseling? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(15):3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153423

Chicago/Turabian StyleKovacevic, Alexander, Stefan Bär, Sebastian Starystach, Michael Elsässer, Thomas van der Locht, Aida Mohammadi Motlagh, Eva Ostermayer, Renate Oberhoffer-Fritz, Peter Ewert, Matthias Gorenflo, and et al. 2021. "Fetal Cardiac Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Does It Affect Parental Counseling?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 15: 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153423

APA StyleKovacevic, A., Bär, S., Starystach, S., Elsässer, M., van der Locht, T., Mohammadi Motlagh, A., Ostermayer, E., Oberhoffer-Fritz, R., Ewert, P., Gorenflo, M., & Wacker-Gussmann, A. (2021). Fetal Cardiac Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: How Does It Affect Parental Counseling? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(15), 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153423