“It’s the Attraction of Winning That Draws You in”—A Qualitative Investigation of Reasons and Facilitators for Videogame Loot Box Engagement in UK Gamers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments and Procedure

2.4. Analytical Process

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Participants

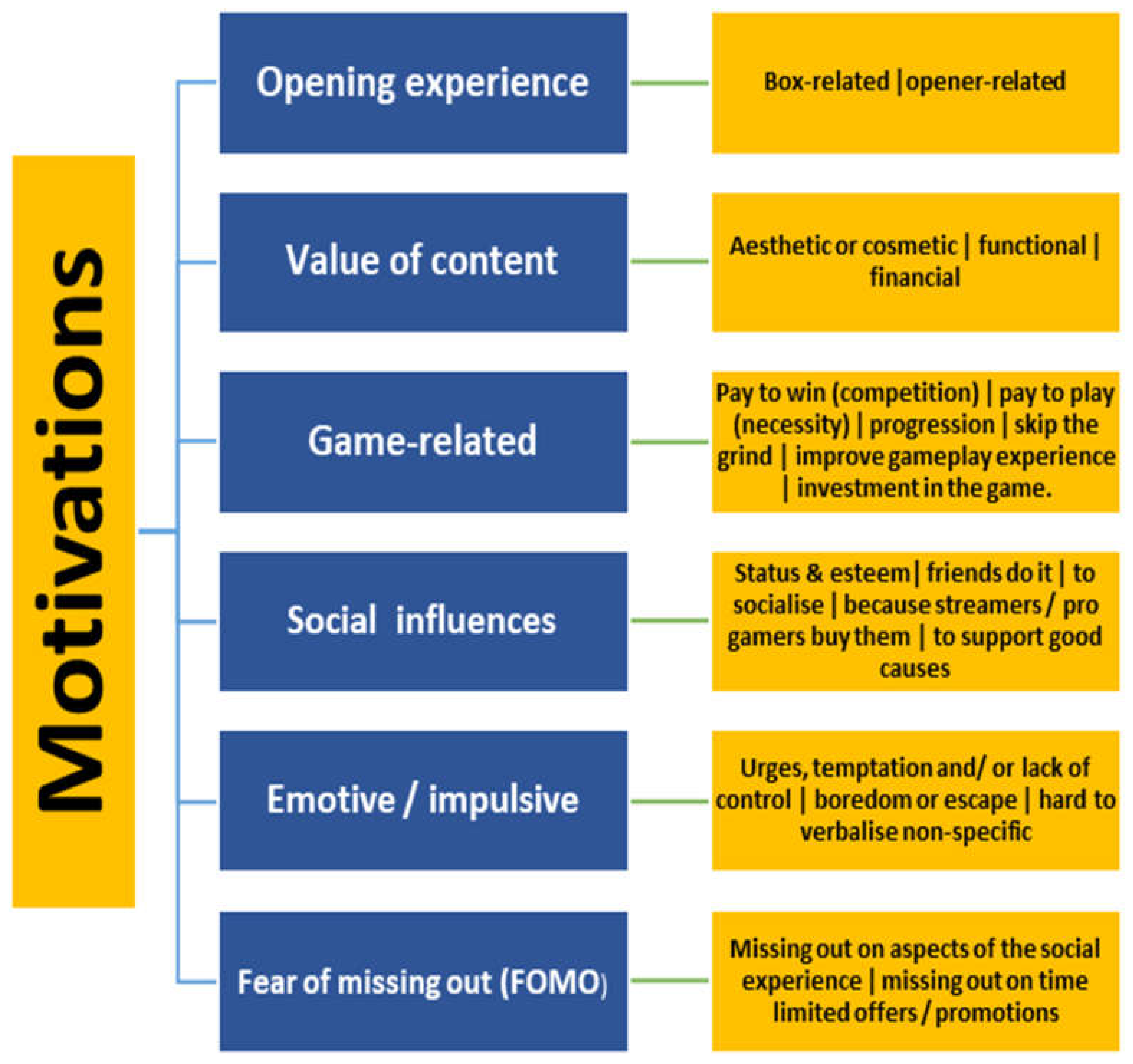

3.2. Loot Box Motivators—Thematic Analysis

3.3. Opening Experience

3.4. Value of Box Contents

3.4.1. Financial Value

3.4.2. Aesthetic or Cosmetic Items

3.4.3. Functional Items

3.5. Game-Related Elements

3.5.1. Progression

3.5.2. Skip the Grind

3.5.3. “Pay to Win”

3.5.4. “Pay to Play”

3.5.5. Enhanced Gameplay Experience

3.5.6. Investing in Games

3.6. Social Factors

3.6.1. Status/Esteem

3.6.2. Influence of Friends/Other Players

3.6.3. Influence of Streamers and/or Professional Gamers

3.6.4. Socialising

3.6.5. Supporting Good Causes

3.7. Emotive/Impulsive Influences

3.7.1. Urges, Temptation and/or Lack of Control

3.7.2. Boredom or Escapism

3.7.3. Hard to Verbalise, Nonspecific Motivations

3.8. Fear of Missing Out

3.9. Triggers/Facilitators

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zendle, D.; Meyer, R.; Cairns, P.; Waters, S.; Ballou, N. The prevalence of loot boxes in mobile and desktop games. Addiction 2020, 115, 1768–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.; Sauer, J.D. Video game loot boxes are psychologically akin to gambling. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 530–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. Is the buying of loot boxes in video games a form of gambling or gaming? Gaming Law Rev. 2018, 22, 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garea, S.; Drummond, A.; Sauer, J.D.; Hall, L.C.; Williams, M. Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Problem Gambling, Excessive Gaming and Loot Box Purchasing. PsyArXiv 2020. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/ug4jy/ (accessed on 30 November 2020). [CrossRef]

- Zendle, D.; Cairns, P. Loot boxes are again linked to problem gambling: Results of a replication study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Close, J.; Spicer, S.G.; Nicklin, L.L.; Uther, M.; Lloyd, J.; Lloyd, H. Secondary analysis of loot box data: Are high-spending “whales” wealthy gamers or problem gamblers? Addict. Behav. 2021, 107, 106851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parliament.uk. ‘Extend the Gambling Act to cover Loot Boxes’. 2020. Available online: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/300171 (accessed on 3 September 2020).

- UK Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). Loot Boxes in Video Games–Call For Evidence. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/loot-boxes-in-video-games-call-for-evidence (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Brooks, G.A.; Clark, L. Associations between loot box use, problematic gaming and gambling, and gambling-related cognitions. Addict. Behav. 2019, 96, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune, E.E.; Goodie, A.S. Cognitive distortions as a component and treatment focus of pathological gambling: A review. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012, 26, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binde, P. Gambling Motivation and Involvement: A Review of Social Science Research; Swedish National Institute of Public Health: Östersund, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.H.; Zack, M. Development and psychometric evaluation of a three-dimensional Gambling Motives Questionnaire. Addiction 2008, 103, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, H.; Moody, A.; Griffiths, M.; Orford, J.; Volberg, R. Defining the online gambler and patterns of behaviour integration: Evidence from the British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2011, 11, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, B.J.I.; McGrath, D.S.; Dechant, K. The Gambling Motives Questionnaire financial: Factor structure, measurement invariance, and relationships with gambling behaviour. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2016, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinaprayoon, T.; Carter, N.T.; Goodie, A.S. The modified Gambling Motivation Scale: Confirmatory factor analysis and links with problem gambling. J. Gambl. Issues 2017, 37, 108–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymen, T.; Smith, O. Gambling and harm in 24/7 capitalism: Reflections from the post-disciplinary present. In Crime, Harm and Consumerism; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon, S.P.; Lambe, L.; Stewart, S.H. Relations of five-factor personality domains to gambling motives in emerging adult gamblers: A longitudinal study. J. Gambl. Issues 2016, 34, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.; Doll, H.; Hawton, K.; Dutton, W.H.; Geddes, J.R.; Goodwin, G.M.; Rogers, R.D. How Psychological Symptoms Relate to Different Motivations for Gambling: An Online Study of Internet Gamblers. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.L.; Delfabbro, P.H. Video Game Monetization (e.g., ‘Loot Boxes’): A Blueprint for Practical Social Responsibility Measures. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahlo, J.; Kaakinen, J.K.; Holm, S.K.; Koponen, A. Digital game dynamics preferences and player types. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2017, 22, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lafrenière, M.-A.K.; Verner-Filion, J.; Vallerand, R.J. Development and validation of the Gaming Motivation Scale (GAMS). Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Volume Two; Van Lange, P.A., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peracchia, S.; Presaghi, F.; Curcio, G. Pathologic Use of Video Games and Motivation: Can the Gaming Motivation Scale (GAMS) Predict Depression and Trait Anxiety? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zendle, D.; Meyer, R.; Over, H. Adolescents and loot boxes: Links with problem gambling and motivations for purchase. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gainsbury, S.M. Gaming-gambling convergence: Research, regulation, and reactions. Gaming Law Rev. 2019, 23, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaa, L. Creating Protocols for Trustworthiness in Qualitative Research. J. Cult. Divers. 2016, 23, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Establishing trustworthiness. Nat. Inq. 1985, 289, 289–327. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, J.A.; Wynne, H.J. The Canadian Problem Gambling Index; Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001; pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pontes, H.M.; Griffiths, M.D. Measuring DSM-5 internet gaming disorder: Development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qin, L.; Cheng, L.; Hu, M.; Liu, Q.; Tong, J.; Hao, W.; Liao, Y. Clarification of the cut-off score for nine-item Internet Gaming Disorder Scale–Short Form (IGDS9-SF) in a Chinese context. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, C.E.; Knox, S.; Thompson, B.J.; Williams, E.N.; Hess, S.A.; Ladany, N. Consensual qualitative research: An update. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pyett, P.M. Validation of Qualitative Research in the “Real World”. Qual. Health Res. 2003, 13, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, C.P.; Lima, N.R.S.; Queluz, F.N.F.R.; Ferrari, B.L.; Hauck, N. The Online Fear of Missing Out Inventory (ON-FoMO): Development and Validation of a New Tool. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2020, 5, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowlabocus, S. ‘Let’s get this thing open’: The pleasures of unboxing videos. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2020, 23, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, T. Enjoying What We Don’t Have: The Political Project of Psychoanalysis; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, T. Capitalism and Desire: The Psychic Cost of Free Markets; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, L.; Lawrence, A.J.; Astley-Jones, F.; Gray, N. Gambling Near-Misses Enhance Motivation to Gamble and Recruit Win-Related Brain Circuitry. Neuron 2009, 61, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wulfert, E.; Franco, C.; Williams, K.; Roland, B.; Maxson, J.H. The role of money in the excitement of gambling. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008, 22, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larche, C.J.; Chini, K.; Lee, C.; Dixon, M.J.; Fernandes, M. Rare loot box rewards trigger larger arousal and reward responses, and greater urge to open more loot boxes. J. Gambl. Stud. 2019, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allen, J.J.; Anderson, C.A. Satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs in the real world and in video games predict internet gaming disorder scores and well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, J.; Williams, R.J.; Schofield, P. Exploring psychological need satisfaction from gambling participation and the moderating influence of game preferences. Int. Gambl. Stud. 2019, 19, 508–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mills, D.J.; Milyavskaya, M.; Mettler, J.; Heath, N.L. Exploring the pull and push underlying problem video game use: A Self-Determination Theory approach. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 135, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Weinstein, N.; Ryan, R.M.; Rigby, C.S. Having to versus Wanting to Play: Background and Consequences of Harmonious versus Obsessive Engagement in Video Games. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hand, M. Boredom: Technology, acceleration, and connected presence in the social media age. In Boredom Studies Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics: World, Finitude, Solitude; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Mills, D.; Nower, L. The relationship of loot box purchases to problem video gaming and problem gambling. Addict. Behav. 2019, 97, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüll, N.D. Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- King, D.L.; Russell, A.M.T.; Delfabbro, P.H.; Polisena, D. Fortnite microtransaction spending was associated with peers’ purchasing behaviors but not gaming disorder symptoms. Addict. Behav. 2020, 104, 106311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymen, T.; Smith, O. Lifestyle gambling, indebtedness and anxiety: A deviant leisure perspective. J. Consum. Cult. 2020, 20, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, O. Contemporary Adulthood and the Night-Time Economy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin, S.L. Sample Size Policy for Qualitative Studies Using In-Depth Interviews. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 1319–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kafai, Y.B.; Richard, G.T.; Tynes, B.M. Diversifying Barbie and Mortal Kombat: Intersectional Perspectives and Inclusive Designs in Gaming; Carnegie Mellon, ETC Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.W.; Xia, M.; Huang, Y. From Minnows to Whales: An Empirical Study of Purchase Behavior in Freemium Social Games. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2015, 20, 177–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.; Sauer, J.D.; Hall, L.C.; Zendle, D.; Loudon, M.R. Why loot boxes could be regulated as gambling. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 986–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Ethnicity | Geography | Education | Marital | Living | Employment | Individual Salary (GBP) | IGD | PGSI | Monthly Spend | Yearly Spend | All Time Spend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alex | 22 | M | White—British | East Mids England | UG higher education | Single | With parents | FT employment | 25,001–30,000 | 21 | 1 | GBP 20 | x3 | GBP 700 |

| Andrew | 20 | M | White—British | North East England | UG higher education | Single | With parents | PT employment | <10,000 | x | x | x | GBP 1000 | x |

| Charlie | 46 | M | White—British | West Mids England | UG higher education | Divorced | Partner/children | Self employed | 40,000+ | 22 | 0 | 0 | GBP 4 | GBP 50 |

| Chris | 25 | M | Gypsy/Irish Traveller | South East Wales | Secondary school | Married | Partner/children | FT employment | 20,001–25,000 | 25 | 2 | GBP 50 | GBP 150 | GBP 3000 |

| Daniel | 26 | M | White—British | West Mids England | College/vocational | Cohabiting | Partner/children | FT furloughed | 25,001–30,000 | 16 | 3 | GBP 50 | GBP 300–500 | x |

| Darren | 31 | M | White—British | East Mids England | Secondary school | Cohabiting | Partner/children | FT employment | 10,000–15,000 | 16 | 4 | GBP 150 | GBP 1000 | GBP 7000 |

| Dean | 26 | M | White—British | South West England | UG higher education | Cohabiting | Partner/children | FT furloughed | 20,001–25,000 | 34 | 10 | x | GBP 2000 | GBP 4000 |

| Debbie | 29 | F | Black—African | South East England | PG masters | Cohabiting | Partner/children | FT employment | 30,001–40,000 | 19 | 0 | GBP 4 | GBP 20 | GBP 200 |

| Emily | 19 | F | White—British | North East England | College/vocational | Cohabiting | Partner/children | Seeking opportunities | Below 10,000 | 11 | 0 | GBP < 10 | GBP 50–100 | GBP 200 |

| Harry | 24 | M | White—British | Highlands—Scotland | UG higher education | Single | Sharing property with non-family | FT employment | 25,001–30,000 | 26 | 0 | x | x | GBP 20 |

| Henry | 18 | M | White—British | South East England | College/vocational | Single | With parents | Seeking opportunities | Not earning | 26 | 0 | GBP 40 | x | x |

| Ian | 22 | M | White—British | South West England | UG higher education | Single | Student housing | FT education | Not earning | 29 | 8 | GBP 100 | GBP 300 | GBP 4000 |

| Kate | 35 | F | White—British | South East England | UG higher education | Cohabiting | With partner | Self employed | <10,000 | 14 | 0 | GBP < 10 | GBP 50 | GBP 100 |

| Les | 28 | M | White—British | South Wales | UG higher education | Single | Sharing property with non-family | FT employment | 30,001–40,000 | 22 | 0 | GBP 4 | GBP 50 | GBP 300 |

| Mia | 18 | F | White—British | South West England | College/vocational | Single | With parents | FT education | Not earning | 31 | 0 | GBP 30 | x | x |

| Natalie | 56 | F | White—British | South East England | UG higher education | Prefer not to say | Living alone | Living with disability | Not earning | 15 | 0 | x | GBP 100 | GBP 100 |

| Neil | 44 | M | White—British | South West England | College/vocational | Cohabiting | Partner/children | FT employment | Above 40,000 | 18 | 18 | GBP 25 | GBP 300 | GBP 1200 |

| Oscar | 34 | M | White—British | South West Wales | PG masters | In a relationship | Partner/children | FT furloughed | 20,001–25,000 | 19 | 0 | GBP 3.50 | GBP 40 | GBP 160 |

| Paul | 40 | M | White—British | North West England | College/vocational | Married | Partner/children | FT employment | 30,001–40,000 | 22 | 4 | GBP 60 | GBP 700 | GBP 3000 |

| Roger | 18 | M | White—British | South East England | College/vocational | Single | With parents | PT furloughed | 10,000–15,000 | 20 | 4 | x | x | GBP 1000 |

| Sarah | 29 | F | White—British | North East England | College/vocational | Married | Partner/children | PT employment | <10,000 | 18 | 0 | x | x | GBP 15 |

| Seb | 21 | M | White—British | North East Scotland | Secondary school | Single | Living alone | FT education | Not earning | 20 | 0 | x | x | GBP 250 |

| Sharon | 24 | F | Chinese | South East England | PG masters | Single | With parents | Other | N/A | 24 | 0 | x | GBP 30 | GBP 100 |

| Spencer | 28 | M | White—Eastern European | North West England | UG higher education | Single | Alone | FT employment | 40,001+ | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | GBP 50–60 |

| Susan | 22 | F | White—British | West Mids England | UG higher education | In a relationship | With parents | FT education | Not earning | 22 | 0 | x | GBP 30 | GBP 250 |

| Tom | 29 | M | White—British | North West England | UG higher education | Single | Living alone | Other | Below 10,000 | 15 | 0 | GBP 2.50 | x | GBP 30 |

| Victoria | 29 | F | White—British | South West England | College/vocational | Married | Partner/children | FT employment | 30,001–40,000 | 20 | 0 | GBP 20–50 | GBP 240–600 | x |

| Zack | 29 | M | White—British | South West England | PG masters | Cohabiting | Partner/children | FT employment | 15,001–20,000 | 14 | 2 | GBP 20–80 | GBP 100 | GBP 300 |

| Opening Experience | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Box-Related Factors | Opener-Related Factors | ||

| “if I buy a loot box now, they definitely make it exciting to do this…there’s a lot of animation that comes with it and that’s quite exciting and thrilling.” (Susan) “It’s, like, a walkout scene, so each player it would be, like, “striker! Left” or “striker, Portugal” and it will start to show the cards after, six seconds of when you opened the pack…It’s definitely become more addictive” (Ian) | “It was fun, you got what you wanted or you didn’t; it was still all good fun.” (Natalie) “Just like a rush…a rush of excitement…just pleasure, really, it was like a hit…Especially if you got a good player, like, a rare player. It was just, like ultimately winning” (Sharon) | ||

| Value of Box Contents | |||

| Financial | Aesthetic/Cosmetic | Functional | |

| “If you got a good player…it was, like, ultimately winning virtual currency, because you could sell that player for virtual currency, so that’s what it was all about.” (Sharon) “If I put in a load of money in at the start, I’m going to create a lot more money for the future.” (Ian) | “It’s just an opportunity for you to buy the skin and buy something that you think looks good” (Les) “there was quite a lot of in-game shame for people who just have the default skins on weapons and characters.” (Mia) | “I sit here and think how much am I going to use this thing” (Spencer) “it’s not so much for display, but for advancement, for me” (Susan) | |

| Game-Related Elements | |||

| Progression | Skip the Grind | Pay to Win | |

| “I play some of the puzzle games, mainly on my phone…and sometimes if a level’s been driving me bonkers for ages and I’m one move away, and I’ve run out of lives, I’ll pay a pound for an extra life.” (Kate) | “You can either spend a lot of time grinding it for free or you can, like, cheat, well—not cheat, but shortcut your way in by just spending money and just getting the content as well” (Sharon) | “just wanting to be able to do better, so, in the games where it give you items, and, so, you get that special item that will help you out…beat that last boss, or help beat more people online.” (Paul) | |

| Pay to Play | Enhanced Game Experience | Investing in Games | |

| “I don’t like it but it’s a necessity, for the sake of me being able to play” (Roger) “if you don’t buy packs or you don’t’ grind the game for hours…it’s just not possible to be competitive.” (Oscar) “if the rest of my team are quite far ahead within a game and I need to catch up to that point…I would fork out.” (Emily) | “I had a lot of fun playing the game…having these load outs, from the loot box were affecting the gameplay, giving me new weapons, making my characters more stronger…made it more fun.” (Harry) | “I like to give back to the developers of it if it’s something that I think looks cool or I’m kind of interested in.” (Tom) “Most of these games that offer them are free to play, so others, some people justify the purchase, saying this game gives me entertainment, so I’m going to pay for it.” (Roger) | |

| Social Factors | |||

| Status and Esteem | Influence of Friends/Others | Influence of Streamers and/or Pro-Gamers | |

| “You could brag to the lads at work, “I just packed so and so in a pack last night…” (Darren) “It was very important to get those achievements and to get these limited-edition items that no one else had, it was kinda like a status thing…in these types of games, you were put higher on the social ranks if you could display these skins…“oh look at everything that I’ve got,” you know? There’s that power that comes behind with it.” (Susan) | “It might be that my friend Gerard gets a really cool skin, and I’m like “well, now I want it”, or, I’m then comparing myself to him, because he’s got it and I don’t” (Zack) “everybody else was doing it, like, ‘ah, yeah you haven’t got it’… I’d probably give in to peer pressure” (Chris) “if you have a default skin, a default load out…they’ll just be rude to you…to get some more respect in the game you do have to have, skins and stuff, but it’s another motivation.” (Mia) | “The influence online is crazy, if there wasn’t influence, I don’t think there would be more sales of loot boxes…” (Ian) “You look at some of the reactions on YouTube and it’s like; if you pull a good player, people go absolutely crazy, like, ‘YES! YES! YES!’ because you pulled that amazing item” (Ian) | |

| Socialising | To Support Good Causes | ||

| “I’d be out with my friends a few of us would all normally play FIFA and we’d be like “oh, actually shall we all just throw like a tenner on some packs?”…see what we can get.” (Oscar) “If I’m opening a loot box and there’s other people that I’m chatting to and they’re opening loot boxes, and you can, it’s a shared experience, they’re, like “ah, great you go that you wanted”, you know, or “ah, sorry about that—maybe next time” and it’s the same, you’re the same with them, it’s a kind of camaraderie, almost, like disappointment on a social scale or happiness on a social scale.” (Natalie) | “They do charity events once a year, or a couple of times a year, where it says like ‘spend GBP 10 and you will get this rideable mount’ and you just move around on it, you fly around on it, and it looks special, and all the money will go to charity…the money goes to a cause” (Roger) | ||

| Emotive/Impulsive Motivations | |||

| Urges, Temptation and/or Lack of Control | Boredom or Escapism | Hard to Verbalise, Non-Specific Motivations | |

| “it was always very difficult to resist the temptation” (Seb) “I realised that was an addiction but then it kept slipping my mind and every time it slipped my mind it sort of got replaced with ‘oh when can I buy more, when do I get more money, when can I buy more’” (Neil) | “Sometimes you sit there, and you think, ‘well, hold on, I’m a little bit bored, I don’t really want to watch TV, I know, I’ll open some FIFA packs, and buy some games add-ons’ and, you know, I’m sure I’m not the first person to say ‘well, I’m just bored…I’ll put money on needlessly’” (Darren) ‘ | “Well, why I did, that’s a tough one isn’t it, the why is probably just the, I don’t know” (Spencer) “I don’t know, really—it’s a bit embarrassing in a group of 20-year-olds, 21-year-olds now, you know, like, to be sitting there putting hundreds of pounds in to what is a football game on Xbox.” (Sharon) | |

| Fear of Missing Out | |||

| “fear of missing out, that’s the, that’s what people are most vulnerable to—especially if they’re just getting in to a game and they think ‘oh wow, I want to really get into this and do well in this game’ or something, and then they put a time limited event on and you think ‘hang on a minute...maybe I need to buy something’” (Sharon) | |||

| Triggers/Facilitators | |||

| Promotions | Special (Time-Limited) Events | Ease of Purchase | |

| “…they would give you, like, 20% extra free if you spent GBP 80 straight up, as opposed to just 20, or they give you a better pack with more chance of getting a good player if you spent more money on the game, so more money on the pack.” (Sharon) | “they would have this time-limited event going on, which brought the rate up and a lot of people… would end up resorting to buying, additional tickets to try and roll for the unit they want” (Sharon) “the advertising is so good…that’s why you continue to put money in, and money in” (Ian) | “you could link a card to your account…it doesn’t feel like you’re spending money…you’re not seeing any money exchange hands.” (Paul) “When you’re gambling online, you have to go through the whole system of signing up, and confirming…on PS4 it’s like, buy, done…I could spend GBP 500 in five seconds.” (Ian) | |

| Theme | Opening Experience | Value of Content | Game Related | Social Influences | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudonym | Box Related | Opener Related | Aesthetic /Cosmetic | Functional | Financial | Pay to Win | Pay to Play | Progression | Skip the Grind | Improve Game Play | Invest in Game | Status and Esteem | Friends/Others Do It | To Socialise | Streamers/Pro Gamers | Good Causes |

| Alex | ||||||||||||||||

| Andrew | ||||||||||||||||

| Charlie | ||||||||||||||||

| Chris | ||||||||||||||||

| Debbie | ||||||||||||||||

| Emily | ||||||||||||||||

| Harry | ||||||||||||||||

| Henry | ||||||||||||||||

| Kate | ||||||||||||||||

| Les | ||||||||||||||||

| Mia | ||||||||||||||||

| Natalie | ||||||||||||||||

| Oscar | ||||||||||||||||

| Sarah | ||||||||||||||||

| Seb | ||||||||||||||||

| Sharon | ||||||||||||||||

| Spencer | ||||||||||||||||

| Susan | ||||||||||||||||

| Tom | ||||||||||||||||

| Victoria | ||||||||||||||||

| Zack | ||||||||||||||||

| Daniel | ||||||||||||||||

| Darren | ||||||||||||||||

| Paul | ||||||||||||||||

| Roger | ||||||||||||||||

| Ian | ||||||||||||||||

| Neil | ||||||||||||||||

| Dean | ||||||||||||||||

| Total | 21 | 23 | 22 | 23 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 24 | 4 | 14 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 3 |

| Amount | Most | Most | Most | Most | Many | Some | Many | Many | Some | Most | Some | Many | Many | Many | Many | Some |

| Theme | Emotive/Impulsive Influences | Fear of Missing Out | Type of Gamer | Style of Gaming | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudonym | Urges/Temptation/Control | Boredom or Escape | Hard to Verbalise/Nonspecific | Missing Out on Social Experience | Missing Out on Time offers/Promotions | Mobile | PC | Console | Cooperative | Competitive | Solo |

| Alex | |||||||||||

| Andrew | |||||||||||

| Charlie | |||||||||||

| Chris | |||||||||||

| Debbie | |||||||||||

| Emily | |||||||||||

| Harry | |||||||||||

| Henry | |||||||||||

| Kate | |||||||||||

| Les | |||||||||||

| Mia | |||||||||||

| Natalie | |||||||||||

| Oscar | |||||||||||

| Sarah | |||||||||||

| Seb | |||||||||||

| Sharon | |||||||||||

| Spencer | |||||||||||

| Susan | |||||||||||

| Tom | |||||||||||

| Victoria | |||||||||||

| Zack | |||||||||||

| Daniel | |||||||||||

| Darren | |||||||||||

| Paul | |||||||||||

| Roger | |||||||||||

| Ian | |||||||||||

| Neil | |||||||||||

| Dean | |||||||||||

| Total | 19 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 18 | 22 | 15 | 23 | 15 | 22 | 22 |

| Amount | Most | Some | Some | Many | Many | Most | Many | Most | Many | Most | Most |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicklin, L.L.; Spicer, S.G.; Close, J.; Parke, J.; Smith, O.; Raymen, T.; Lloyd, H.; Lloyd, J. “It’s the Attraction of Winning That Draws You in”—A Qualitative Investigation of Reasons and Facilitators for Videogame Loot Box Engagement in UK Gamers. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10102103

Nicklin LL, Spicer SG, Close J, Parke J, Smith O, Raymen T, Lloyd H, Lloyd J. “It’s the Attraction of Winning That Draws You in”—A Qualitative Investigation of Reasons and Facilitators for Videogame Loot Box Engagement in UK Gamers. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(10):2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10102103

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicklin, Laura Louise, Stuart Gordon Spicer, James Close, Jonathan Parke, Oliver Smith, Thomas Raymen, Helen Lloyd, and Joanne Lloyd. 2021. "“It’s the Attraction of Winning That Draws You in”—A Qualitative Investigation of Reasons and Facilitators for Videogame Loot Box Engagement in UK Gamers" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 10: 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10102103

APA StyleNicklin, L. L., Spicer, S. G., Close, J., Parke, J., Smith, O., Raymen, T., Lloyd, H., & Lloyd, J. (2021). “It’s the Attraction of Winning That Draws You in”—A Qualitative Investigation of Reasons and Facilitators for Videogame Loot Box Engagement in UK Gamers. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(10), 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10102103