Study of the Effect of Inorganic Particles on the Gas Transport Properties of Glassy Polyimides for Selective CO2 and H2O Separation

Abstract

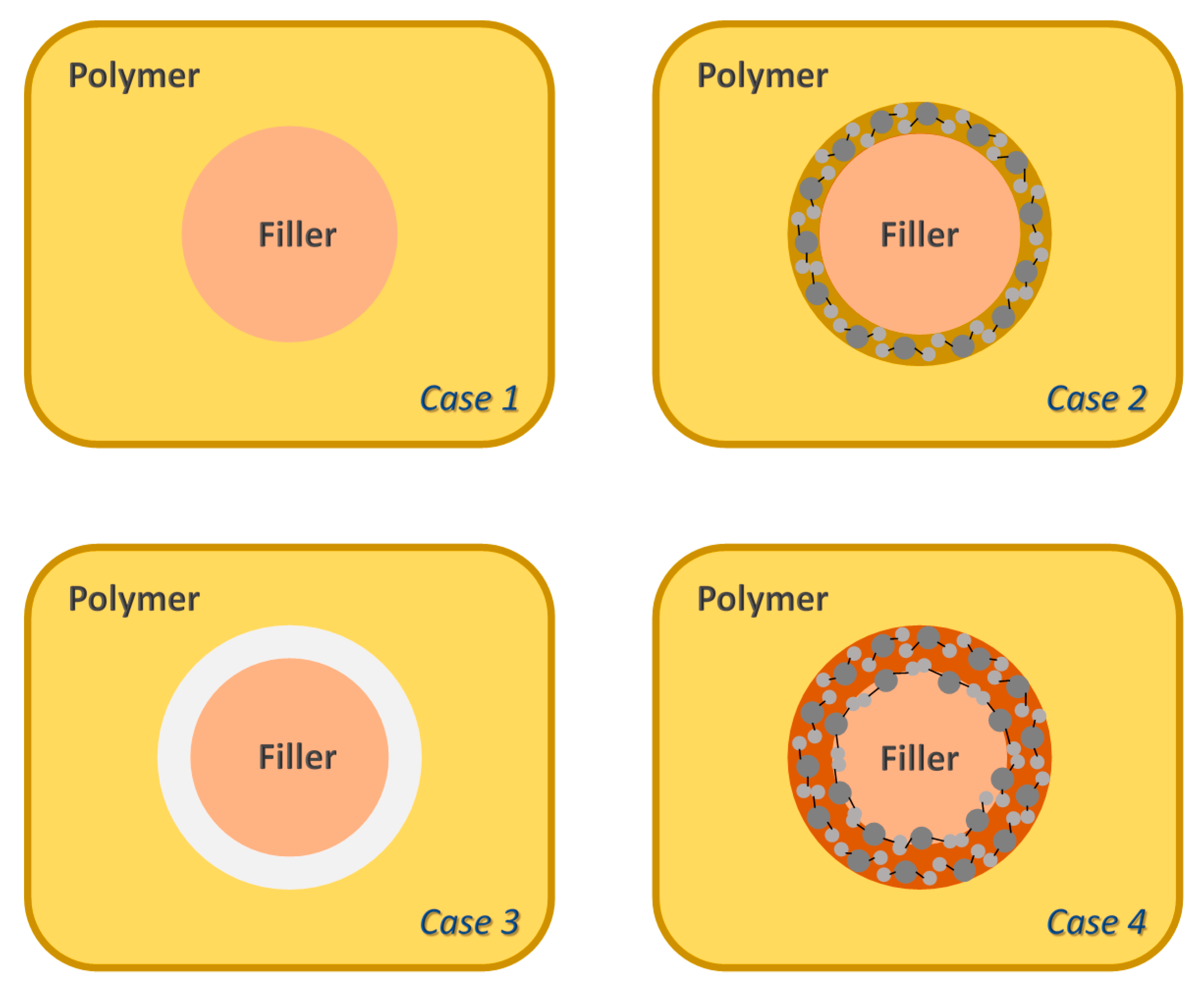

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Polymers

2.1.2. Solvents

2.1.3. Particles

2.2. Membranes Fabrication

2.2.1. Inorganic Particles Dispersion

2.2.2. Membranes Formation

2.3. Samples Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thermal Properties

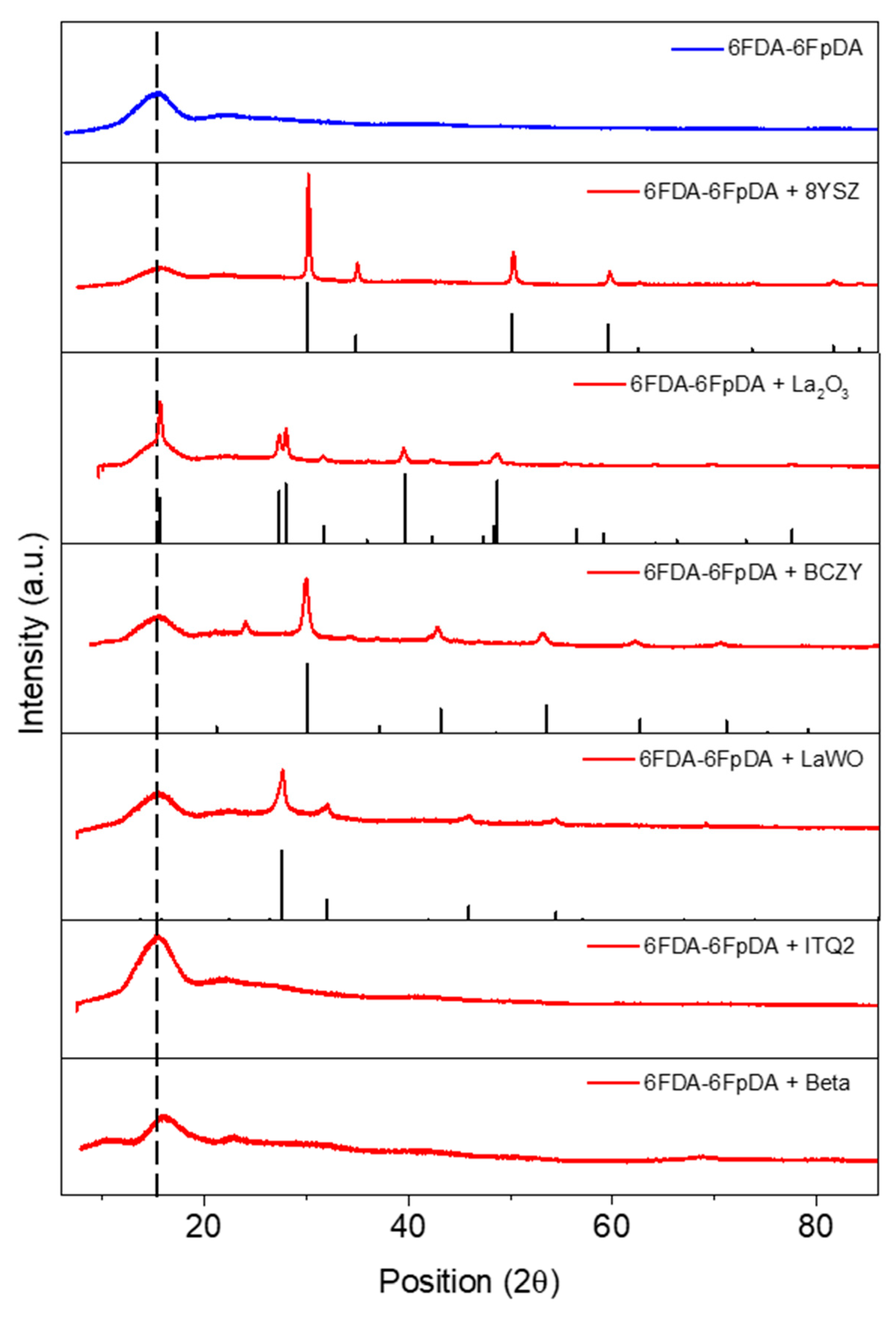

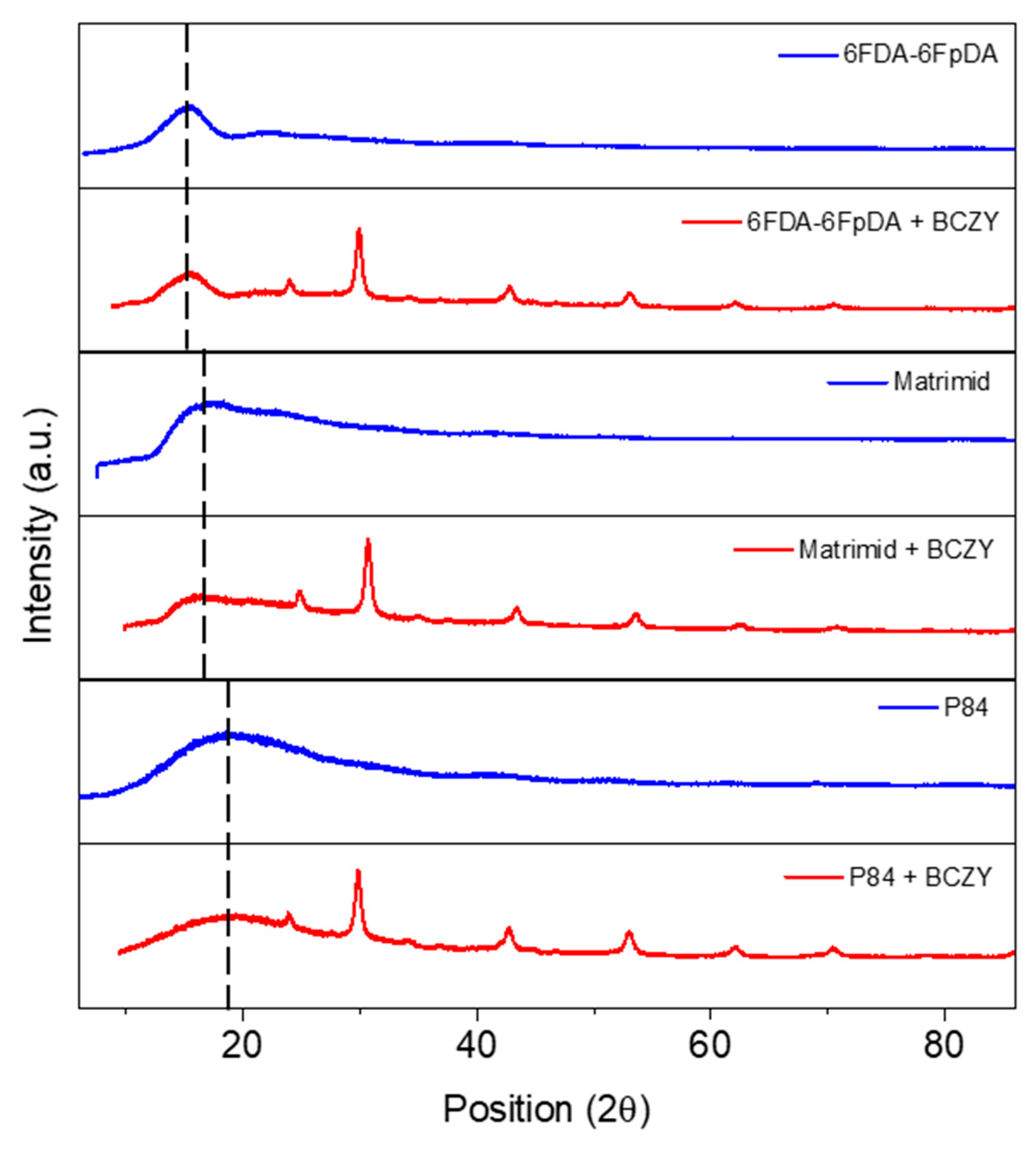

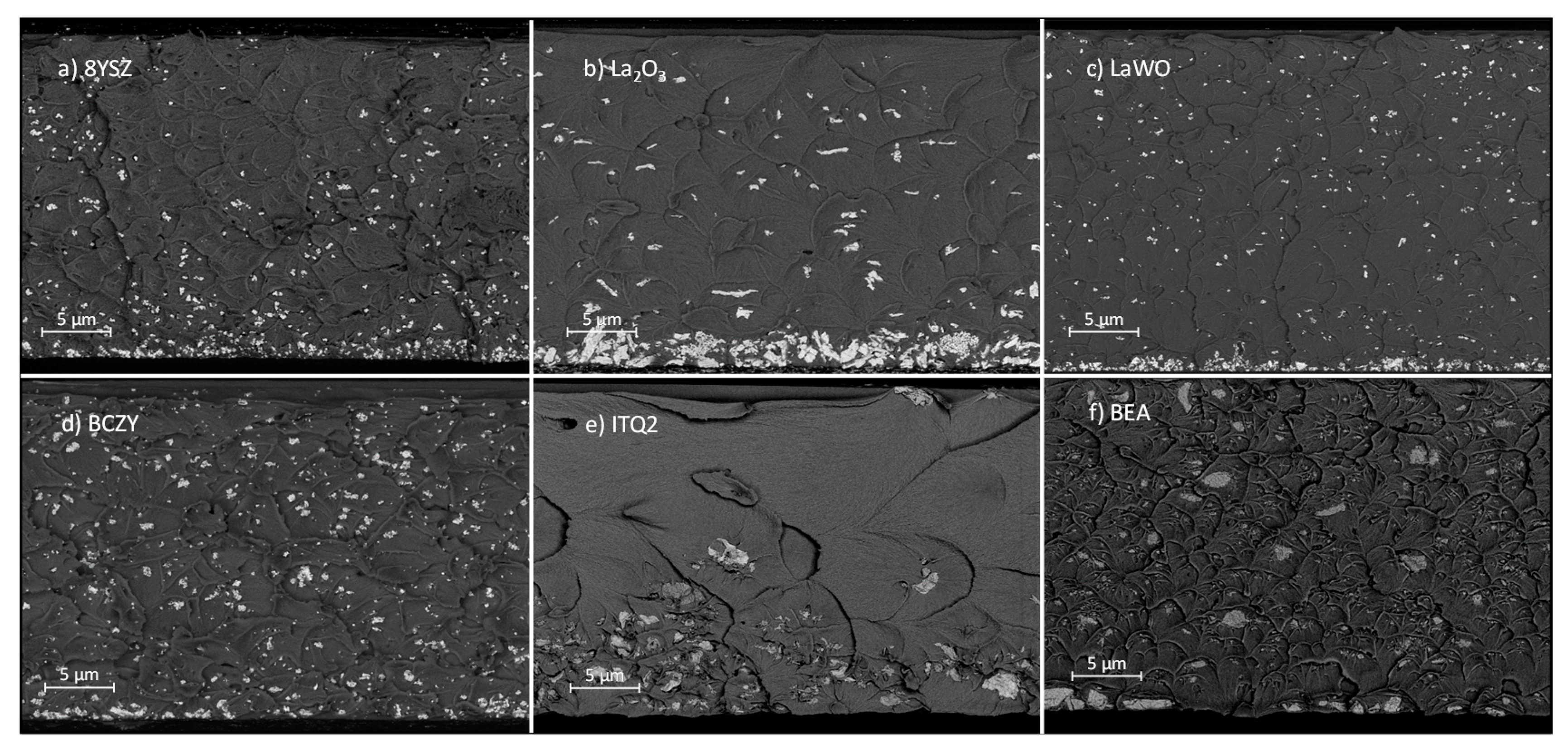

3.2. Microstructure Characterization

3.3. Gas Transport Properties

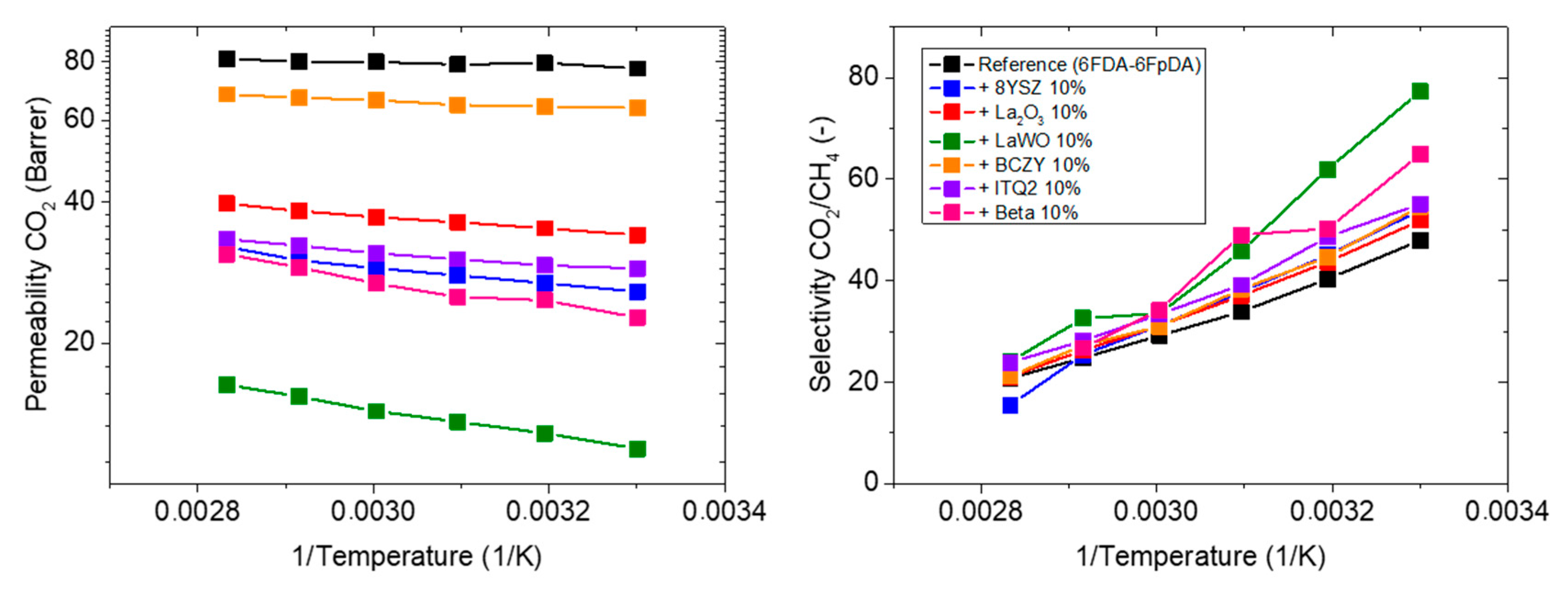

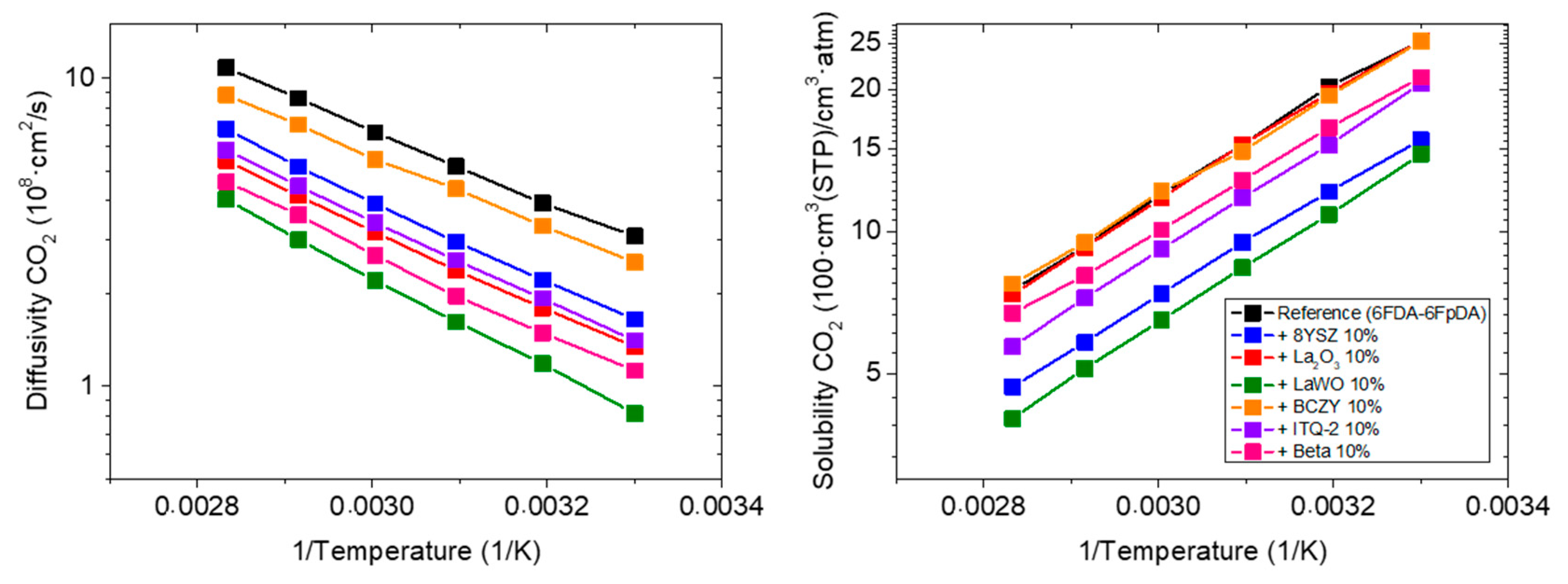

3.3.1. Influence of the Particle Type

3.3.2. Influence of the Particle Content

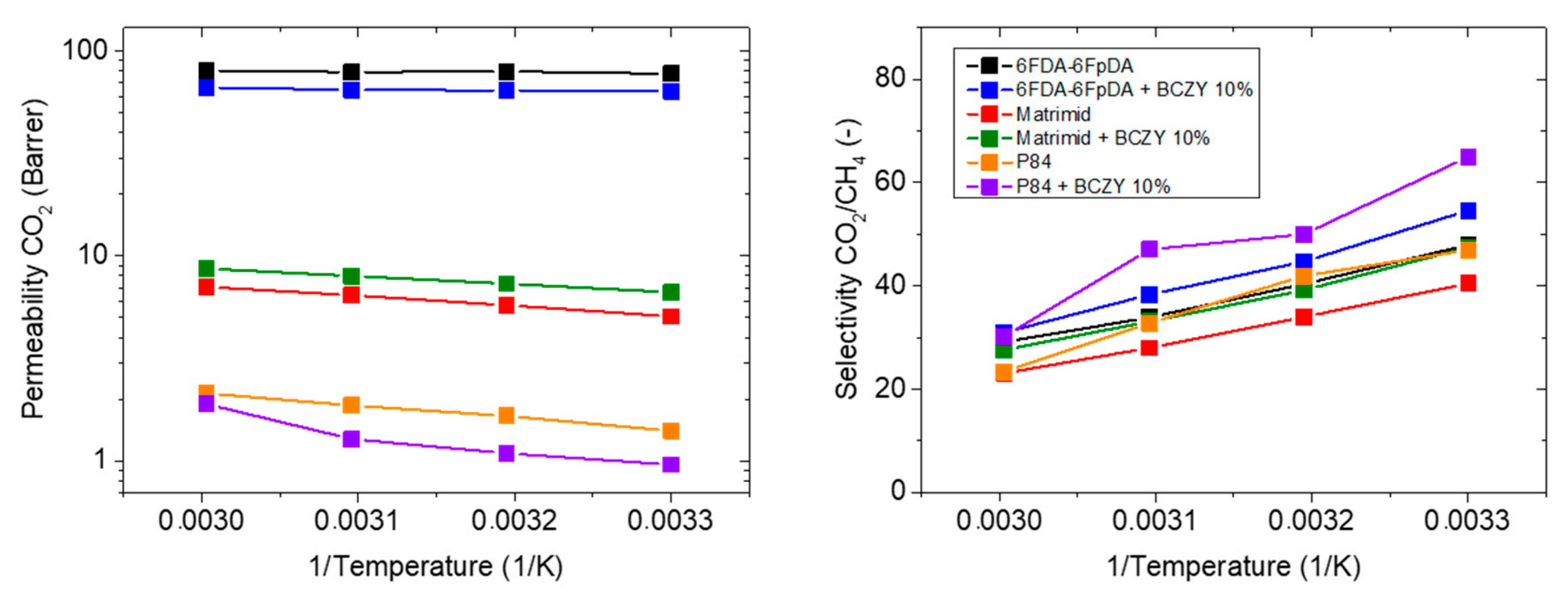

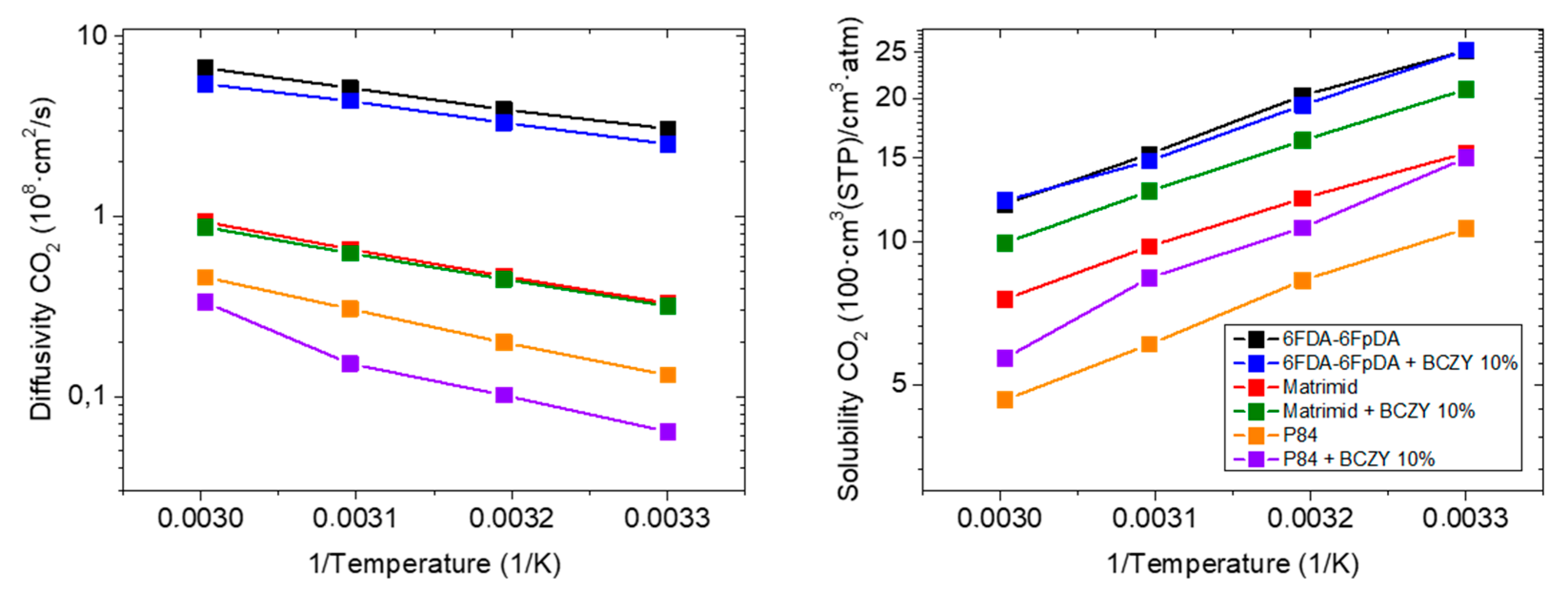

3.3.3. Influence of the Polymer Matrix

3.3.4. Transport of Water Vapor in MMMs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santi Kulprathipanja, R.W.N.; Norman, N. Li Separation of Fluids by Means of Mixed Matrix Membranes. U.S. Patent 4,740,219, 26 April 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kulprathipanja, S. Mixed matrix membrane development. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 984, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robeson, L.M. The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, D.R.; Âmpol’skij, U.P. Polymeric Gas Separation Membranes; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.W. Research needs in the membrane separation industry: Looking back, looking forward. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 362, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stünkel, S.; Drescher, A.; Wind, J.; Brinkmann, T.; Repke, J.U.; Wozny, G. Carbon dioxide capture for the oxidative coupling of methane process—A case study in mini-plant scale. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011, 89, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, D. Mixed matrix membranes for natural gas upgrading: Current status and opportunities. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 4139–4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koros, W.; Zhang, C. Materials for next-generation molecularly selective synthetic membranes. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, G.; Wang, S.; Yu, S.; Pan, F.; Wu, H.; Jiang, Z. Recent advances in the fabrication of advanced composite membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 10058–10077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, C.; Qiu, W.; Yi, S.; Chernikova, V.; Chen, Z.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Shekhah, O.; Eddaoudi, M.; et al. Enhanced CO2/CH4 separation performance of a mixed matrix membrane based on tailored mof-polymer formulations. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.-H.; Liu, J.; Lee, J.S.; Koros, W.J.; Jones, C.W.; Nair, S. Facile high-yield solvothermal deposition of inorganic nanostructures on zeolite crystals for mixed matrix membrane fabrication. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14662–14663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornoza, B.; Téllez, C.; Coronas, J. Mixed matrix membranes comprising glassy polymers and dispersed mesoporous silica spheres for gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 368, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, M.; Marchese, J.; Garis, E.; Ochoa, N.; Pagliero, C. Abs copolymer-activated carbon mixed matrix membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 243, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, L.; Johnson, J.K.; Marand, E. Polysulfone and functionalized carbon nanotube mixed matrix membranes for gas separation: Theory and experiment. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 294, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Carson, C.; Ward, J.; Tannenbaum, R.; Koros, W. Metal organic framework mixed matrix membranes for gas separations. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 131, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, N.B. A perfect match. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 216–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dechnik, J.; Sumby, C.J.; Janiak, C. Enhancing mixed-matrix membrane performance with metal–organic framework additives. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 4467–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastani, D.; Esmaeili, N.; Asadollahi, M. Polymeric mixed matrix membranes containing zeolites as a filler for gas separation applications: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreon, M.A. Membranes for Gas Separations; Colorado School of Mines: Golden, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Greer, D.W.; O’Leary, B.W. Advanced materials and membranes for gas separations: The uop approach. In Nanotechnology: Delivering on the Promise Volume 2; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 1224, pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dechnik, J.; Gascon, J.; Doonan, C.J.; Janiak, C.; Sumby, C.J. Mixed-matrix membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 9292–9310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chuah, C.Y.; Nie, L.; Bae, T.-H. Enhancing the mechanical strength and CO2/CH4 separation performance of polymeric membranes by incorporating amine-appended porous polymers. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 569, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, M.; Jørgensen, M.; Krebs, F.C. The teraton challenge. A review of fixation and transformation of carbon dioxide. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 43–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltner, M.; Makaruk, A.; Harasek, M. Review on available biogas upgrading technologies and innovations towards advanced solutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah Khan, I.; Hafiz Dzarfan Othman, M.; Hashim, H.; Matsuura, T.; Ismail, A.F.; Rezaei-DashtArzhandi, M.; Wan Azelee, I. Biogas as a renewable energy fuel—A review of biogas upgrading, utilisation and storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 150, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañez-Hernández, L.; Hernandez De Lira, I.; Rafael-Galindo, G.; de Lourdes Froto Madariaga, M.; Balagurusamy, N. Sustainable production of biogas from renewable sources: Global overview, scale up opportunities and potential market trends. Sustain. Biotechnol. Enzymatic Resour. Renew. Energy 2018, 325–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W.; Lokhandwala, K. Natural gas processing with membranes: An overview. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 2109–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sunarso, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, R. Current status and development of membranes for co2/ch4 separation: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 12, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezakazemi, M.; Ebadi Amooghin, A.; Montazer-Rahmati, M.M.; Ismail, A.F.; Matsuura, T. State-of-the-art membrane based CO2 separation using mixed matrix membranes (mmms): An overview on current status and future directions. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 817–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidaki, I.; Treu, L.; Tsapekos, P.; Luo, G.; Campanaro, S.; Wenzel, H.; Kougias, P.G. Biogas upgrading and utilization: Current status and perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong-Woo, J.; Dong-Hoon, L. Gas membranes for CO2/CH4 (biogas) separation: A review. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2015, 32, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Murali, R.S.; Sankarshana, T.; Sridhar, S. Air separation by polymer-based membrane technology. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2013, 42, 130–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehashi, S.; Chen, G.Q.; Ciddor, L.; Chaffee, A.; Kentish, S.E. The impact of water vapor on co2 separation performance of mixed matrix membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 492, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuer, K.D. Proton-conducting oxides. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2003, 33, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugsrud, R. Defects and transport properties in Ln6WO12 (Ln = La, Nd, Gd, Er). Solid State Ion. 2007, 178, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Anselmi-Tamburini, U.; Park, H.J.; Martin, M.; Munir, Z.A. Unprecedented room-temperature electrical power generation using nanoscale fluorite-structured oxide electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Barquín, A.; Casado Coterillo, C.; Palomino, M.; Valencia, S.; Irabien, A. Lta/poly(1-trimethylsilyl-1-propyne) mixedmatrix membranes for high-temperature CO2/N2 separatio. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2015, 38, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansaloni, L.; Deng, L. 7–advances in polymer-inorganic hybrids as membrane materials. In Recent Developments in Polymer Macro, Micro and Nano Blends; Visakh, P.M., Markovic, G., Pasquini, D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 163–206. [Google Scholar]

- Maghami, M.; Abdelrasoul, A. Zeolite Mixed Matrix Membranes (Zeolite-Mmms) for Sustainable Engineering; West Virginia University: Morgantown, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tena, A.; Shishatskiy, S.; Meis, D.; Wind, J.; Filiz, V.; Abetz, V. Influence of the composition and imidization route on the chain packing and gas separation properties of fluorinated copolyimides. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 5839–5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorihuela, S.; Tena, A.; Shishatskiy, S.; Escolástico, S.; Brinkmann, T.; Serra, J.; Abetz, V. Gas separation properties of polyimide thin films on ceramic supports for high temperature applications. Membranes 2018, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corma, A.; Fornés, V.; Guil, J.M.; Pergher, S.; Maesen, T.L.M.; Buglass, J.G. Preparation, characterisation and catalytic activity of itq-2, a delaminated zeolite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2000, 38, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Mori, M.; Inukai, M.; Nitani, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Miyanaga, T.; Igawa, N.; Kitamura, N.; Ishida, N.; Idemoto, Y. Effect of annealing on crystal and local structures of doped zirconia using experimental and computational methods. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 8447–8458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, F.; Sougi, M.; Meriel, P.; Herr, A.; Meyer, A. Etude par diffraction de neutrons des structures magnétiques de tbbe 13 à basse température. J. Phys. 1980, 41, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherb, T.; Kimber, S.A.J.; Stephan, C.; Henry, P.F.; Schumacher, G.; Escolastico, S.; Serra, J.M.; Seeger, J.; Just, J.; Hill, A.H.; et al. Nanoscale order in the frustrated mixed conductor La5.6WO12−δ. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2016, 49, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Kishida, K.; Shinoda, K.; Inui, H.; Uda, T. A comprehensive understanding of structure and site occupancy of y in y-doped BaZrO3. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 3027–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morejudo, S.H.; Zanón, R.; Escolástico, S.; Yuste-Tirados, I.; Malerød-Fjeld, H.; Vestre, P.K.; Coors, W.G.; Martínez, A.; Norby, T.; Serra, J.M.; et al. Direct conversion of methane to aromatics in a catalytic co-ionic membrane reactor. Science 2016, 353, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IZA Structure Comission. Available online: http://www.iza-structure.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2018).

- Lilleparg, J.; Georgopanos, P.; Emmler, T.; Shishatskiy, S. Effect of the reactive amino and glycidyl ether terminated polyethylene oxide additives on the gas transport properties of pebax® bulk and thin film composite membranes. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 11763–11772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dai, Y.; Johnson, J.R.; Karvan, O.; Koros, W.J. High performance zif-8/6fda-dam mixed matrix membrane for propylene/propane separations. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 389, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Barquín, A.; Casado Coterillo, C.; Palomino, M.; Valencia, S.; Irabien, A. Permselectivity improvement in membranes for CO2/N2 separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 157, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabetghadam, A.; Seoane, B.; Keskin, D.; Duim, N.; Rodenas, T.; Shahid, S.; Sorribas, S.; Guillouzer, C.L.; Clet, G.; Tellez, C.; et al. Metal organic framework crystals in mixed-matrix membranes: Impact of the filler morphology on the gas separation performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3154–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khayet, M.; García-Payo, M.C. X-ray diffraction study of polyethersulfone polymer, flat-sheet and hollow fibers prepared from the same under different gas-gaps. Desalination 2009, 245, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio, R.; Palacio, L.; Prádanos, P.; Hernández, A.; Lozano, Á.E.; Marcos, Á.; de la Campa, J.G.; de Abajo, J. Gas separation of 6fda–6fpda membranes: Effect of the solvent on polymer surfaces and permselectivity. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 293, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylkowski, N.A.G.B.a.B. Chemical Synergies: From the Lab to in Silico Modelling; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Calle, M.; Lozano, A.E.; de Abajo, J.; de la Campa, J.G.; Álvarez, C. Design of gas separation membranes derived of rigid aromatic polyimides. 1. Polymers from diamines containing di-tert-butyl side groups. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 365, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Tan, J.; Zeng, Y.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, X. Barrier and thermal properties of polyimide derived from a diamine monomer containing a rigid planar moiety. Polym. Int. 2017, 66, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yampolskii, Y.; Shishatskii, S.; Alentiev, A.; Loza, K. Correlations with and prediction of activation energies of gas permeation and diffusion in glassy polymers. J. Membr. Sci. 1998, 148, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, A.; Ching, O.P.; Shariff, A.B.M. Current status and future prospect of polymer-layered silicate mixed-matrix membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2016, 39, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.-H.; Long, J.R. CO2/N2 separations with mixed-matrix membranes containing mg2(dobdc) nanocrystals. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3565–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castarlenas, S.; Téllez, C.; Coronas, J. Gas separation with mixed matrix membranes obtained from mof uio-66-graphite oxide hybrids. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 526, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galve, A.; Sieffert, D.; Vispe, E.; Téllez, C.; Coronas, J.; Staudt, C. Copolyimide mixed matrix membranes with oriented microporous titanosilicate jdf-l1 sheet particles. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 370, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoba, M.; Bhagiyalakshmi, M.; Alqaheem, Y.; Alomair, A.A.; Pérez, A.; Rana, M.S. Recent progress of fillers in mixed matrix membranes for CO2 separation: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 188, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Particles | 8YSZ | La2O3 | LaWO | BCZY | ITQ-2 | Beta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | 8% mol of Y2O3 stabilized ZrO2 (Tosoh) | Co-precipitation from La(NO3)3. Calcined 800 °C/5 h | La5.4WO12 (CerPoTech). Calcined 950 °C/6 h | BaCe0.2Zr0.7Y0.1O3 (CerPoTech). Calcined 950 °C/6 h | ITQ-2 zeolite. Si/Al = 50 | Zeolite nano-crystalline. Si/Al = 12.5 |

| Structure |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Density (g/cm2) | 5.95 | 6.56 | 6.58 | 6.14 | - | - |

| BET area (m2/g) | 6.0 | 2.9 | 9.4 | 31.4 | >700 | >700 |

| Size (nm) | 20–80 | 60–100 | 30–120 | 30–100 | Thin sheets (2.5 thick) | 10–30 |

| Uses | Solid electrolyte in solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC) | Ferroelectric materials and as feedstock for catalysts | Asymmetric membranes for hydrogen separation | Asymmetric membranes for hydrogen separation | Catalysis | Catalysis |

| Sample Description | Tmax loss | Theor. wt.% | RM wt.% | Tg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6FDA-6FpDA | 550 °C | 0 | 0 | 311.1 °C |

| +10 wt.% 8YSZ | 550 °C | 10 | 9.8 | 300.2 °C |

| +10 wt.% La2O3 | 550 °C | 10 | 8.1 | 302.4 °C |

| +10 wt.% LaWO | 550 °C | 10 | 8.1 | 290.6 °C |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 550 °C | 10 | 10.0 | 311.2 °C |

| +10 wt.% ITQ-2 | 550 °C | 10 | 0 | 294.7 °C |

| +10 wt.% Beta | 550 °C | 10 | 0 | 294.5 °C |

| 6FDA-6FpDA | 550 °C | 0 | 0 | 311.1 °C |

| +1 wt.% BCZY | 550 °C | 1 | 0 | 314.2 °C |

| +5 wt.% BCZY | 550 °C | 5 | 4.9 | 312.5 °C |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 550 °C | 10 | 10.0 | 311.2 °C |

| +15 wt.% BCZY | 550 °C | 15 | 16.8 | 307.9 °C |

| +20 wt.% BCZY | 550 °C | 20 | 27.2 | 306.3 °C |

| 6FDA-6FpDA | 550 °C | 0 | 0 | 311.1 °C |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 550 °C | 10 | 10.0 | 311.2 °C |

| Matrimid® | 560 °C | 0 | 0 | 320.2 °C |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 560 °C | 10 | 13.3 | 315.7 °C |

| P84® | 580 °C | 0 | 0 | 322.4 °C |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 580 °C | 10 | 7.2 | 318.2 °C |

| Membrane Sample Description | CO2 Permeability (Barrer) | CO2/CH4 Selectivity (-) | CO2 Permeability Variation (%) | CO2/CH4 Selectivity Variation (%) | Activation Energy (KJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6FDA-6FpDA (Reference) | 77.4 | 48.0 | - | - | 0.69 |

| +10 wt.% 8YSZ | 25.8 | 53.9 | −67 | +12 | 3.73 |

| +10 wt.% La2O3 | 34.1 | 51.9 | −56 | +8 | 2.69 |

| +10 wt.% LaWO | 11.9 | 77.3 | −85 | +61 | 5.51 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 63.8 | 54.6 | −18 | +14 | 1.22 |

| +10 wt.% ITQ-2 | 28.9 | 55.1 | −63 | +15 | 2.63 |

| +10 wt.% Beta | 22.7 | 64.9 | −71 | +35 | 4.98 |

| Membrane Sample Description | CO2 Permeability (Barrer) | CO2/CH4 Selectivity (-) | CO2 Permeability Variation (%) | CO2/CH4 Selectivity Variation (%) | Activation Energy (KJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6FDA-6FpDA (Reference) | 77.4 | 48.0 | - | - | 0.69 |

| +1 wt.% BCZY | 61.4 | 49.7 | −21 | +3.6 | 2.56 |

| +5 wt.% BCZY | 45.5 | 49.6 | −41 | +3.3 | 1.89 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 63.8 | 54.6 | −18 | +14 | 1.22 |

| +15 wt.% BCZY | 66.0 | 47.8 | −15 | −0.3 | 0.57 |

| +20 wt.% BCZY | 59.7 | 45.1 | −23 | −6.0 | 1.46 |

| Membrane Sample Description | CO2 Permeability (Barrer) | CO2/CH4 Selectivity (-) | CO2 Permeability Variation (%) | CO2/CH4 Selectivity Variation (%) | Activation Energy (KJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6FDA-6FpDA (Reference) | 77.4 | 48.0 | - | - | 0.69 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 63.8 | 54.6 | −18 | +14 | 1.22 |

| Matrimid® | 5.1 | 40.5 | - | - | 9.30 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 6.7 | 47.5 | +31 | +17 | 7.42 |

| P84® | 1.4 | 47.0 | - | - | 11.64 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 1.0 | 64.6 | −32 | +38 | 18.33 |

| H2O Permeability (Barrer) | H2O/CO2 Selectivity (-) | Activation Energy (KJ/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6FDA-6FpDA | 3875 | 50.06 | −3.34 |

| +10 wt.% 8YSZ | 1998 | 77.48 | −2.22 |

| +10 wt.% La2O3 | 2381 | 69.85 | −2.79 |

| +10 wt.% LaWO | 1287 | 108.30 | −1.35 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 3319 | 52.02 | −3.31 |

| +10 wt.% ITQ-2 | 2015 | 69.70 | −1.31 |

| +10 wt.% Beta | 1914 | 84.35 | 0.69 |

| 6FDA-6FpDA | 3875 | 50.06 | −3.34 |

| +1 wt.% BCZY | 3144 | 51.20 | −2.30 |

| +5 wt.% BCZY | 2766 | 60.83 | −2.23 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 3319 | 52.02 | −3.31 |

| +15 wt.% BCZY | 3276 | 49.67 | −2.13 |

| +20 wt.% BCZY | 3108 | 52.03 | −2.28 |

| 6FDA-6FpDA | 3875 | 50.06 | −3.34 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 3319 | 52.02 | −3.31 |

| Matrimid® | 1524 | 300.60 | 0.87 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 1835 | 276.02 | −1.16 |

| P84® | 1226 | 875.71 | 2.36 |

| +10 wt.% BCZY | 821 | 856.40 | 1.73 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escorihuela, S.; Valero, L.; Tena, A.; Shishatskiy, S.; Escolástico, S.; Brinkmann, T.; Serra, J.M. Study of the Effect of Inorganic Particles on the Gas Transport Properties of Glassy Polyimides for Selective CO2 and H2O Separation. Membranes 2018, 8, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes8040128

Escorihuela S, Valero L, Tena A, Shishatskiy S, Escolástico S, Brinkmann T, Serra JM. Study of the Effect of Inorganic Particles on the Gas Transport Properties of Glassy Polyimides for Selective CO2 and H2O Separation. Membranes. 2018; 8(4):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes8040128

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscorihuela, Sara, Lucía Valero, Alberto Tena, Sergey Shishatskiy, Sonia Escolástico, Torsten Brinkmann, and Jose Manuel Serra. 2018. "Study of the Effect of Inorganic Particles on the Gas Transport Properties of Glassy Polyimides for Selective CO2 and H2O Separation" Membranes 8, no. 4: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes8040128

APA StyleEscorihuela, S., Valero, L., Tena, A., Shishatskiy, S., Escolástico, S., Brinkmann, T., & Serra, J. M. (2018). Study of the Effect of Inorganic Particles on the Gas Transport Properties of Glassy Polyimides for Selective CO2 and H2O Separation. Membranes, 8(4), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes8040128