Characterization of the Regenerative Capacity of Membranes in the Presence of Fouling by Microalgae Using Detergents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

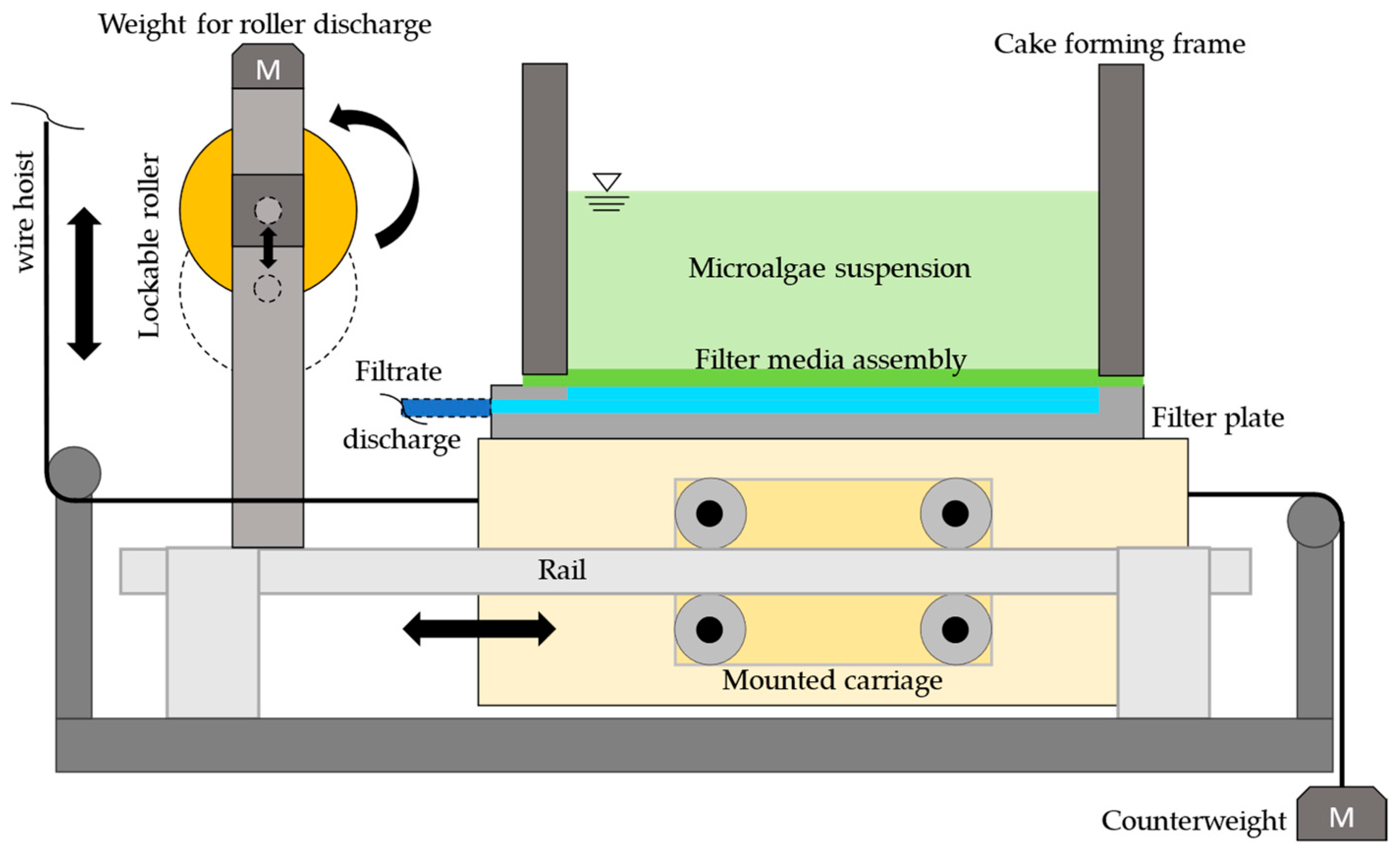

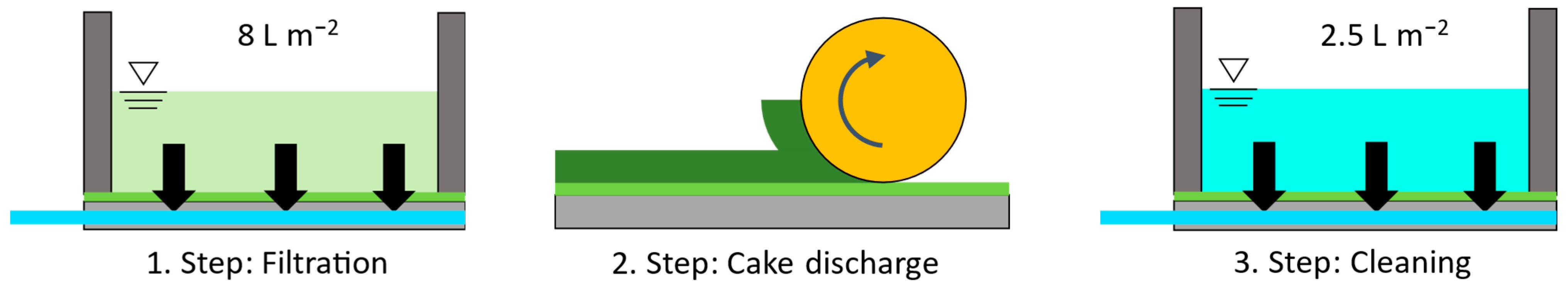

2.2. Experimental Setup and Procedure

3. Results

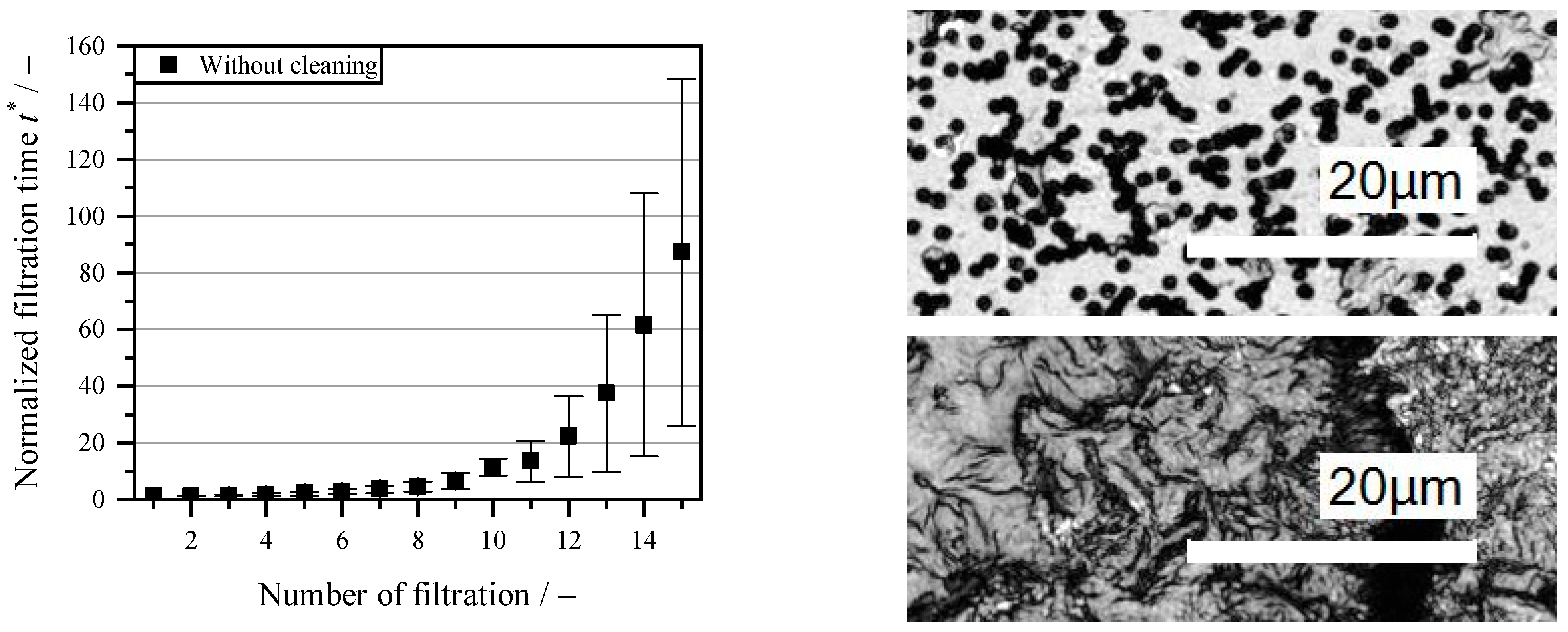

3.1. Filtration Without Cleaning Agents

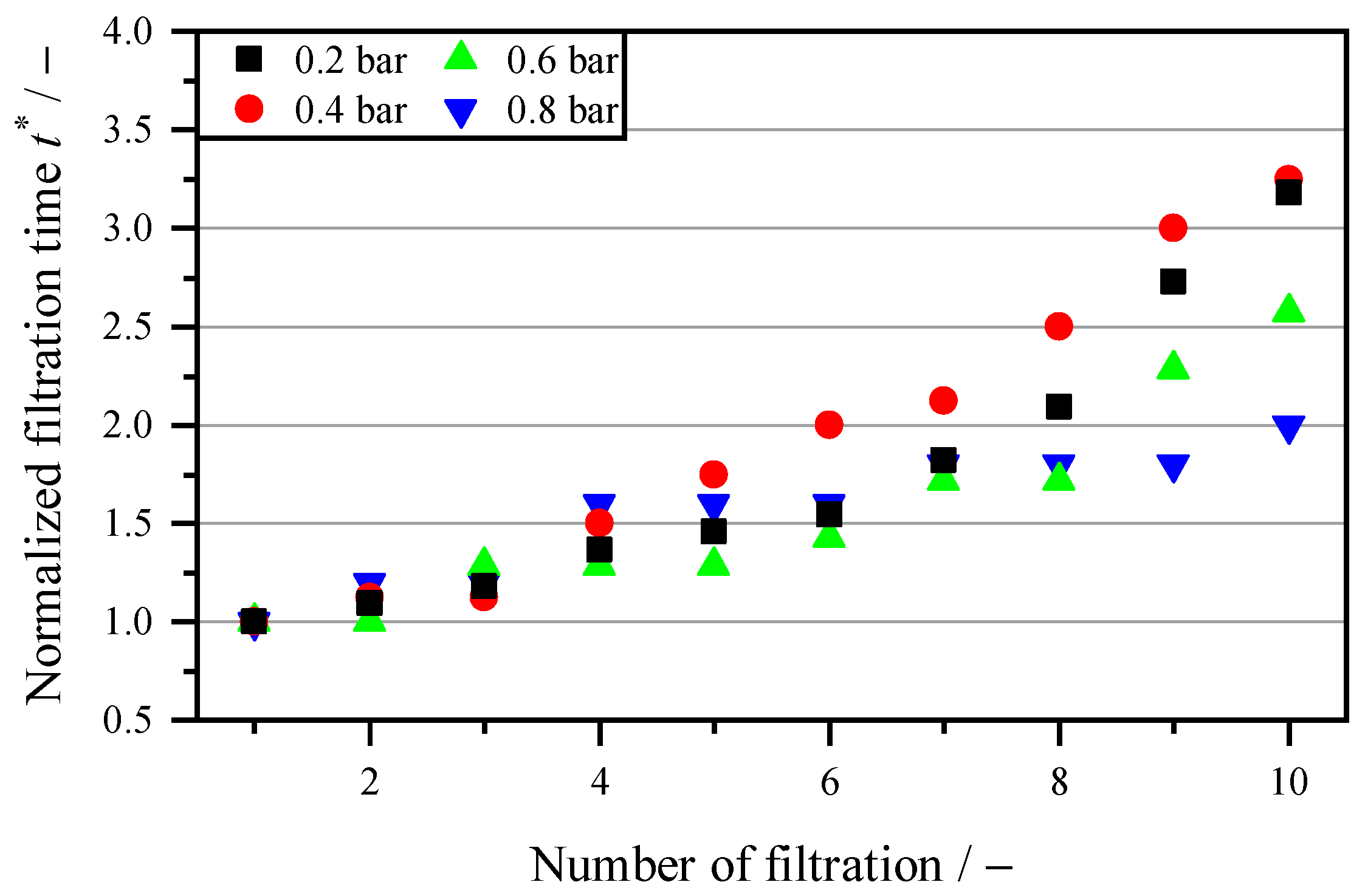

3.2. Mechanical Regeneration Through Backwashing

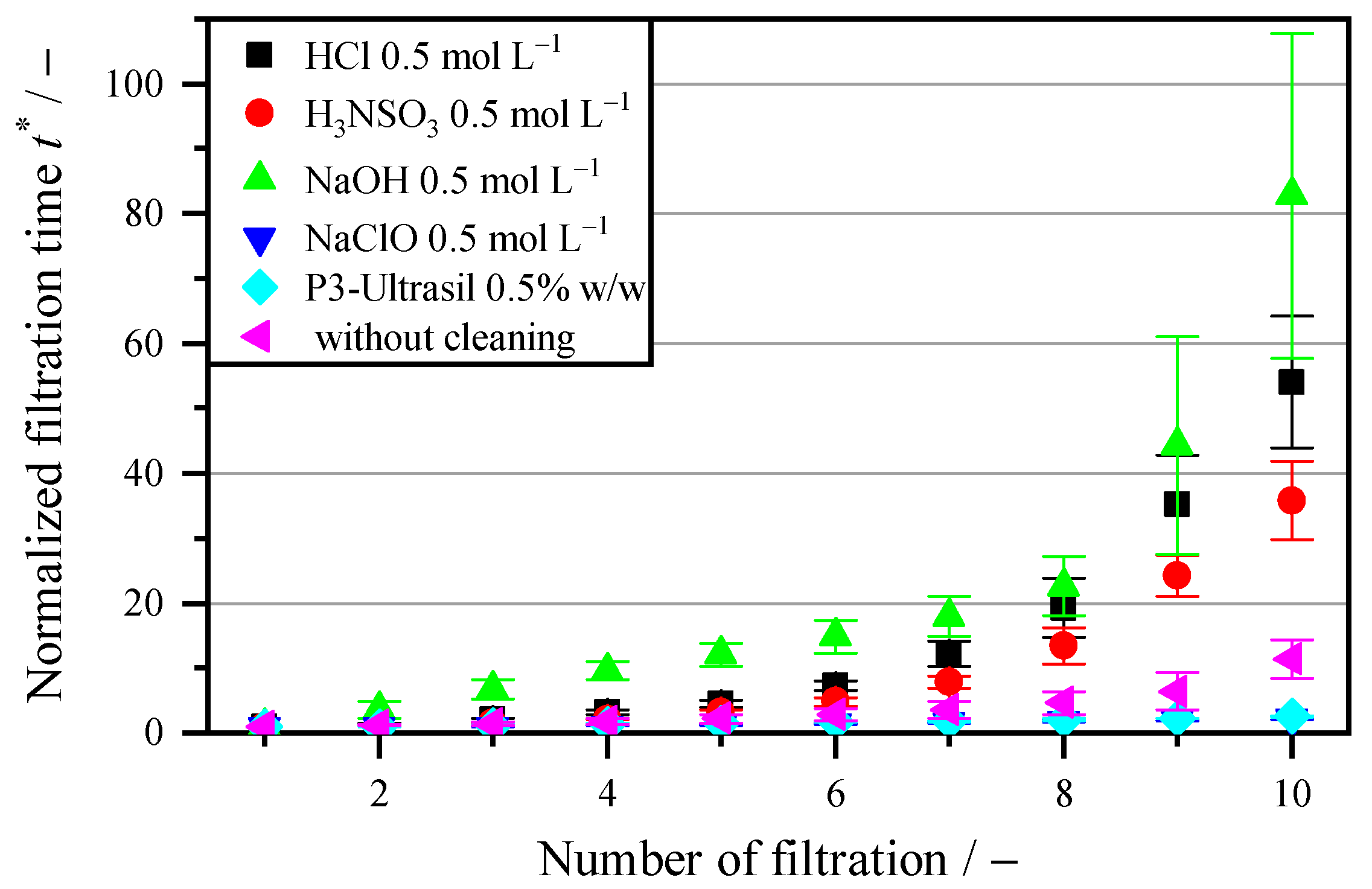

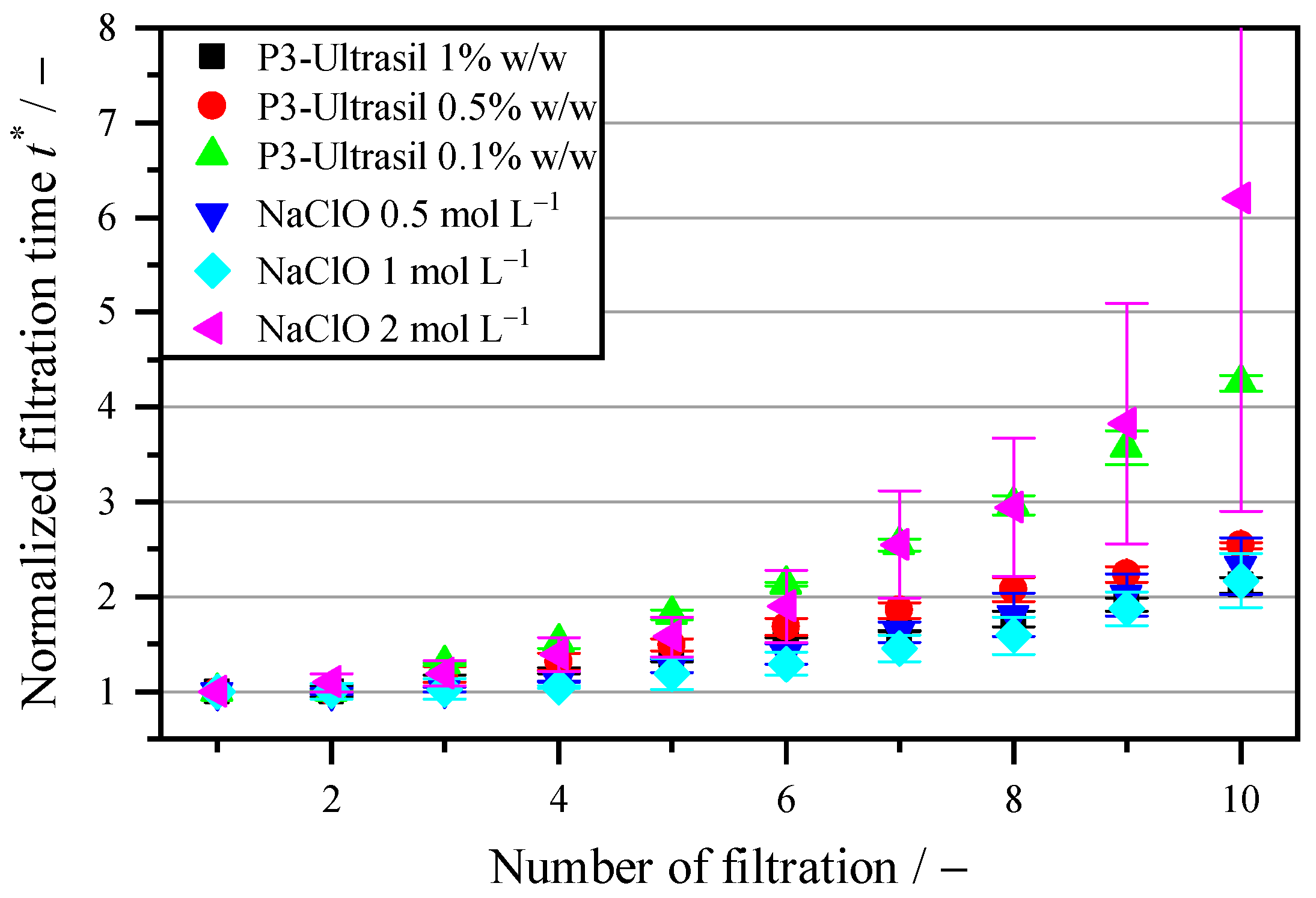

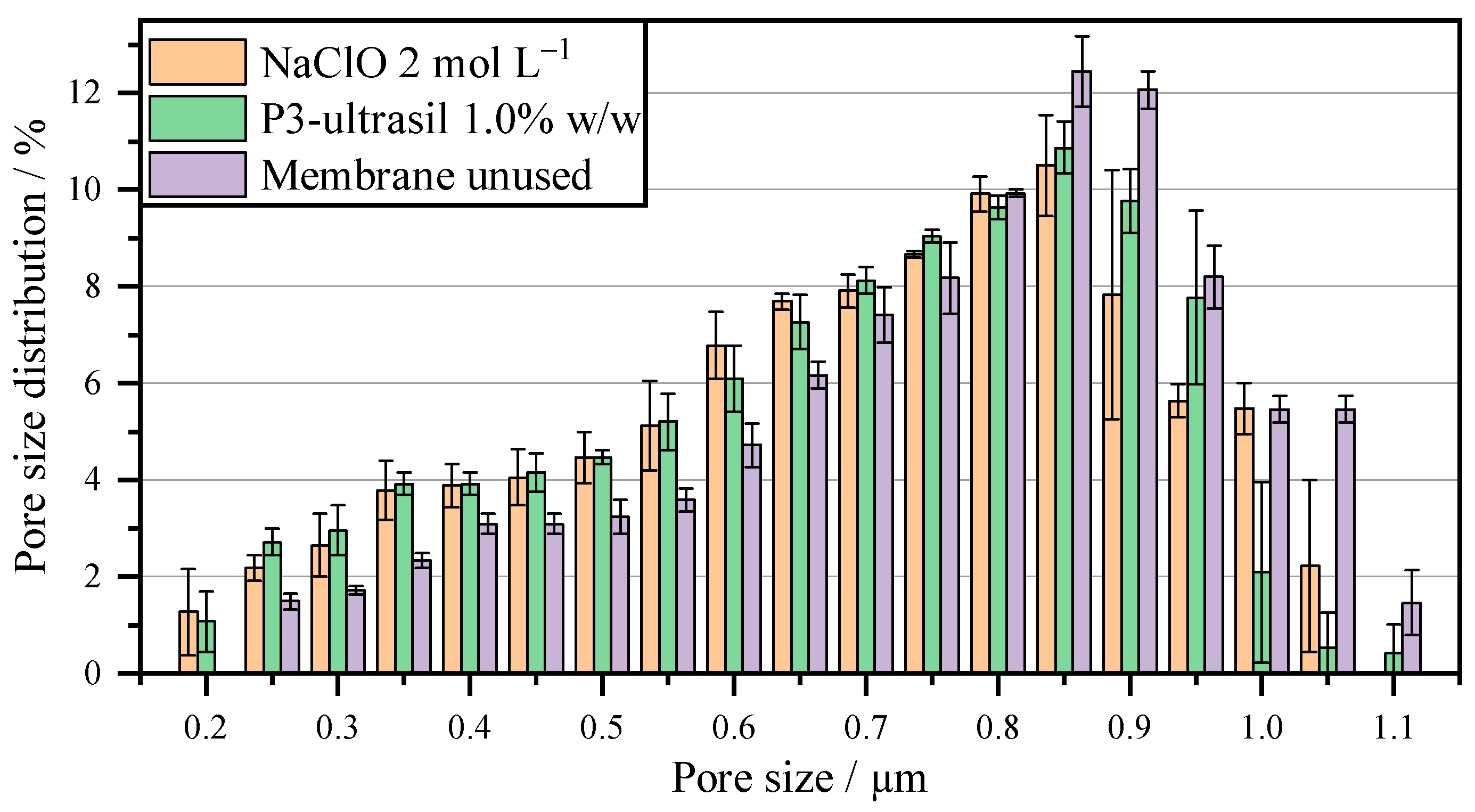

3.3. Influence of Different Chemical Cleaning Agents

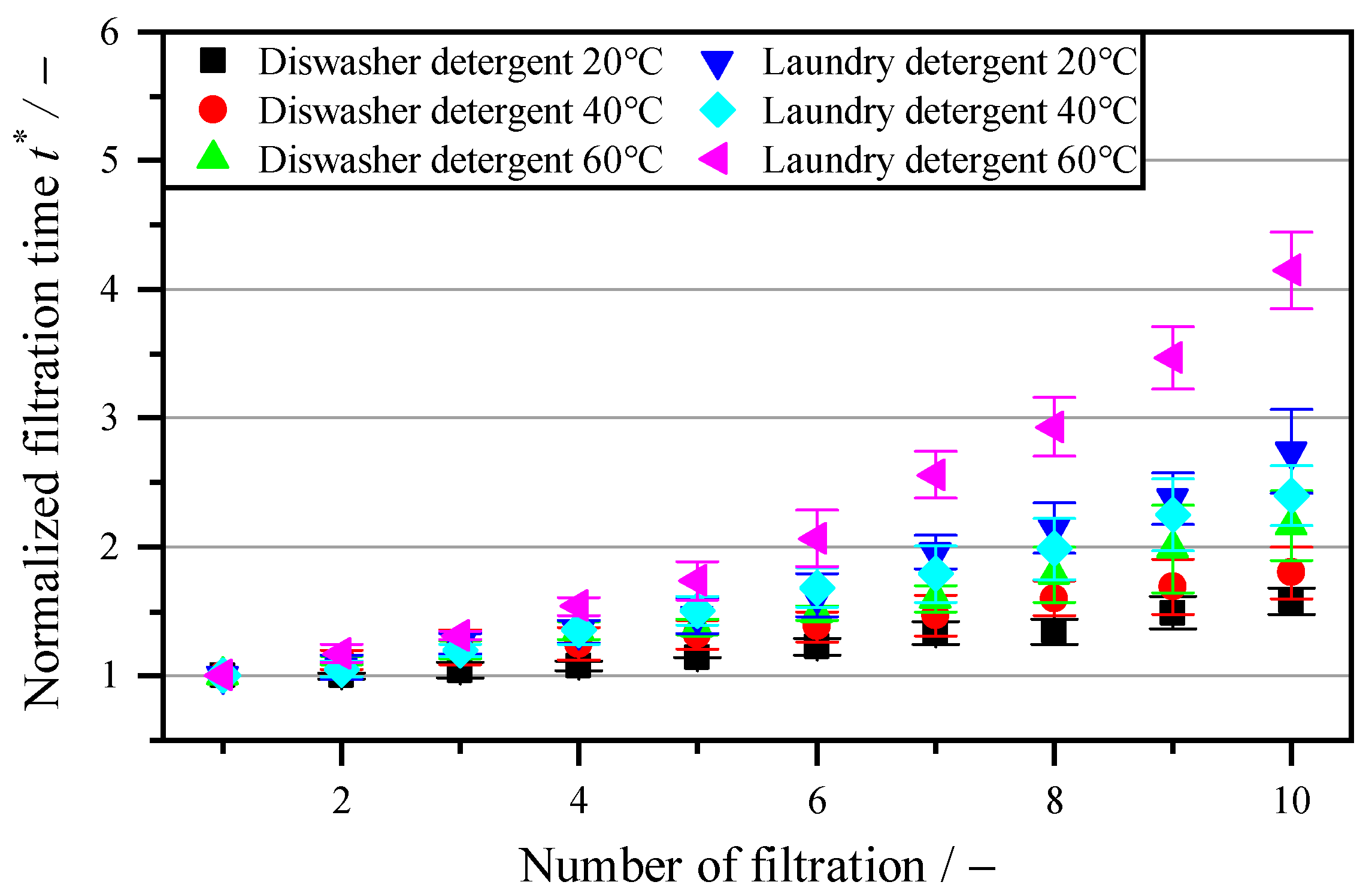

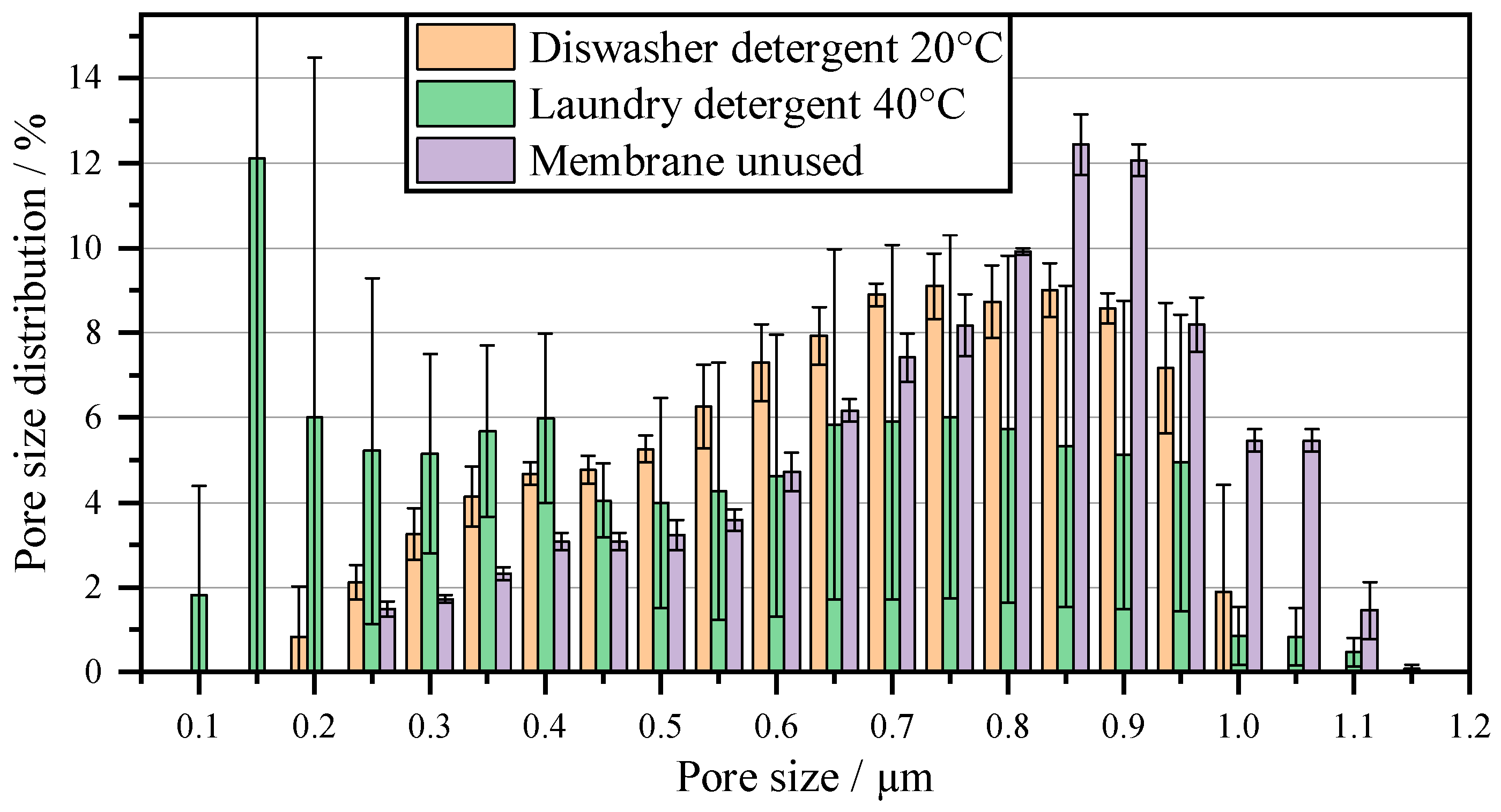

3.4. Regeneration with Biological–Chemical Cleaning Agents

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| dcap | Diameter of the capillary pressure | m |

| d | Diameter | m |

| g | Gravity | m∙s−2 |

| mB | Mass in point B | kg |

| Pcap | Capillary pressure | Pa |

| qP | Line pressure force of the roller | N∙m−1 |

| t0 | Filtration time with new membrane | s |

| tcycle | Filtration time per cycle | s |

| t* | Normalized filtration time | - |

| x10.3 | Mass/volume-related diameter | µm |

| x50.3 | Mass/volume-related modal value | µm |

| x90.3 | Mass/volume-related diameter | µm |

| γL | Surface tension of the liquid | N∙m−1 |

| Δp | Pressure difference | Pa |

| ηL | Dynamic viscosity of the liquid | Pa∙s |

| θ | Contact angle of the liquid | ° |

| AOM | Algal organic matter | |

| HCl | Hydrochloric acid | |

| H3NSO3 | Sulfamic acid | |

| MFP | Mean flow pore size | |

| NaClO | Sodium hypochlorite | |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide | |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate | |

| TEP | Transparent exopolymer particles |

References

- Borowitzka, M.A.; Beardall, J.; Raven, J.A. (Eds.) The Physiology of Microalgae, 1st ed.; Developments in Applied Phycology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24943-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, R.L. Algae: The World’s Most Important “Plants”—An Introduction. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2013, 18, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tua, C.; Ficara, E.; Mezzanotte, V.; Rigamonti, L. Integration of a Side-Stream Microalgae Process into a Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant: A Life Cycle Analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 279, 111605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, V.; Buonerba, A.; Zarra, T.; Oliva, G.; Belgiorno, V.; Boguniewicz-Zablocka, J.; Naddeo, V. Innovative Membrane Photobioreactor for Sustainable CO2 Capture and Utilization. Chemosphere 2021, 273, 129682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Melkonian, M.; Andersen, R.A. Algal Biodiversity. Phycologia 1996, 35, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-K.; Ravichandran, Y.D.; Khan, S.B.; Kim, Y.T. Prospective of the Cosmeceuticals Derived from Marine Organisms. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2008, 13, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolaore, P.; Joannis-Cassan, C.; Duran, E.; Isambert, A. Commercial Applications of Microalgae. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2006, 101, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, J.N.; Oyler, G.A.; Wilkinson, L.; Betenbaugh, M.J. A Green Light for Engineered Algae: Redirecting Metabolism to Fuel a Biotechnology Revolution. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, G.B.; Abdelaziz, A.E.M.; Hallenbeck, P.C. Algal Biofuels: Challenges and Opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 145, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, A.F.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Fortunato, L. Membrane Fouling in Algal Separation Processes: A Review of Influencing Factors and Mechanisms. Front. Chem. Eng. 2021, 3, 687422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanzada, N.K.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Khatri, M.; Ahmed, F.E.; Ibrahim, Y.; Hilal, N. Sustainability in Membrane Technology: Membrane Recycling and Fabrication Using Recycled Waste. Membranes 2024, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sáez, L.; Landaburu-Aguirre, J.; García-Calvo, E.; Molina, S. Application of Recycled Ultrafiltration Membranes in an Aerobic Membrane Bioreactor (aMBR): A Validation Study. Membranes 2024, 14, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Andritsos, N.; Karabelas, A.; Hoek, E.; Schneider, R.; Nyström, M. Fouling in Nanofiltration. In Nanofiltration—Principles and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anlauf, H. Wet Cake Filtration: Fundamentals, Equipment, and Strategies; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-527-34606-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, D.S.; Devi, E.G.; Subikshaa, V.S.; Sethi, P.; Patil, A.; Chakraborty, A.; Venkataraman, S.; Kumar, V.V. Recent Advances in Various Cleaning Strategies to Control Membrane Fouling: A Comprehensive Review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marudhupandi, T.; Sathishkumar, R.; Kumar, T.T.A. Heterotrophic Cultivation of Nannochloropsis Salina for Enhancing Biomass and Lipid Production. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 10, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, Y.S.H.; Abu-Shamleh, A. Harvesting of Microalgae by Centrifugation for Biodiesel Production: A Review. Algal Res. 2020, 51, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chu, H.; Zhou, X.; Dong, B. Dewatering of Chlorella Pyrenoidosa Using Diatomite Dynamic Membrane: Filtration Performance, Membrane Fouling and Cake Behavior. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 113, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, T. Harvesting of Microalgae Scenedesmus sp. Using Polyvinylidene Fluoride Microfiltration Membrane. Desalination Water Treat. 2012, 45, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Bokhary, A.; Maleki, E.; Liao, B. A Review of Membrane Fouling and Its Control in Algal-Related Membrane Processes. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 264, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, H.; Fu, B.; Xu, R.; Fu, Q. Algal Fouling and Extracellular Organic Matter Removal in Powdered Activated Carbon-Submerged Hollow Fiber Ultrafiltration Membrane Systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Fu, Q. Algal Fouling of Microfiltration and Ultrafiltration Membranes and Control Strategies: A Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 203, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrfeld, E.; Bott, R. Continuous Filtration without Gas Throughput—Using Membrane Filter Media. Filtr. Sep. 1990, 27, 274–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Badireddy, A.R. A Critical Review on Electric Field-Assisted Membrane Processes: Implications for Fouling Control, Water Recovery, and Future Prospects. Membranes 2021, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.Y. Role of Spacers in Osmotic Membrane Desalination: Advances, Challenges, Practical and Artificial Intelligence-Driven Solutions. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 201, 107587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.A.; Dalle, M.-A.; Janasz, F.; Leyer, S. Novel Spacer Geometries for Membrane Distillation Mixing Enhancement. Desalination 2024, 580, 117513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.P.; Kim, S.L.; Ting, Y.P. Optimization of Membrane Physical and Chemical Cleaning by a Statistically Designed Approach. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 219, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Meng, F.; Lu, H.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.; He, X. Simultaneous Alkali Supplementation and Fouling Mitigation in Membrane Bioreactors by On-Line NaOH Backwashing. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 457, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskooki, A.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Maskooki, A. Cleaning of Spiralwound Ultrafiltration Membranes Using Ultrasound and Alkaline Solution of EDTA. Desalination 2010, 264, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. Introduction to Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. Volume 2: Enzymes, Proteins and Bioinformatics. In IOP Expanding Physics; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-7503-1302-5. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Aguado, M.J.; Wiley, D.E.; Fane, A.G. Enzymatic and Detergent Cleaning of a Polysulfone Ultrafiltration Membrane Fouled with BSA and Whey. J. Membr. Sci. 1996, 117, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Columbia, M. Enzymatic Control of Alginate Fouling of Dead-End MF and UF Ceramic Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 381, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, S.; Lin, C.-J.; Chen, D. Inorganic Fouling of Pressure-Driven Membrane Processes—A Critical Review. Desalination 2010, 250, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, R.T. A Technical Review of Haematococcus Algae. NatuRose Tech. Bull. 1999, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Do Carmo Cesário, C.; Soares, J.; Cossolin, J.F.S.; Almeida, A.V.M.; Bermudez Sierra, J.J.; De Oliveira Leite, M.; Nunes, M.C.; Serrão, J.E.; Martins, M.A.; Dos Reis Coimbra, J.S. Biochemical and Morphological Characterization of Freshwater Microalga Tetradesmus obliquus (Chlorophyta: Chlorophyceae). Protoplasma 2022, 259, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, T.; Rautenbach, R. Membranverfahren: Grundlagen der Modul- und Anlagenauslegung; VDI-Buch; 3 aktualisierte und erweiterte Auflage; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; ISBN 978-3-540-34328-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Wang, S.; Xie, P.; Zou, Y.; Wan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wiesner, M.R. Chemical Cleaning of Algae-Fouled Ultrafiltration (UF) Membrane by Sodium Hypochlorite (NaClO): Characterization of Membrane and Formation of Halogenated by-Products. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 598, 117662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achaw, O.-W.; Danso-Boateng, E. Soaps and Detergents. In Chemical and Process Industries; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–37. ISBN 978-3-030-79138-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bächle, V.; Gleiß, M.; Nirschl, H. Influence of Particles on the Roller Discharge of Thin-Film Filtration without Gas Throughput. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2024, 47, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Z.; Anlauf, H.; Nirschl, H. Thin-Film Filtration of Difficult-to-Filter Suspensions Using Polymeric Membranes. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2021, 44, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ji, C.; Li, J.-Q.; Hu, Y.-X.; Xu, X.-H.; An, Y.; Cheng, L.-H. Understanding the Interaction Mechanism of Algal Cells and Soluble Algal Products Foulants in Forward Osmosis Dewatering. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 620, 118835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psoch, C.; Schiewer, S. Anti-Fouling Application of Air Sparging and Backflushing for MBR. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 283, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jander, G.; Jahr, K.F.; Schulze, G.; Simon, J. Maßanalyse: Theorie und Praxis der Titrationen mit Chemischen und Physikalischen Indikationen, 16th ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2003; ISBN 978-3-11-017098-6. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Wan, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Xie, P. Removal of Membrane Fouling and Control of Halogenated By-Products by a Combined Cleaning Process with Peroxides and Sodium Hypochlorite. Water 2023, 15, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, G.; Schagerlöf, H.; Morkeberg Krogh, K.B.; Jönsson, A.-S.; Lipnizki, F. Investigations of Alkaline and Enzymatic Membrane Cleaning of Ultrafiltration Membranes Fouled by Thermomechanical Pulping Process Water. Membranes 2018, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, D.; Flores, R.A.; Saldaña, M.D.A. Cellulose Fiber Isolation and Characterization from Sweet Blue Lupin Hull and Canola Straw. J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 2773–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MFP in µm | MFP in µm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| P3-Ultrasil 1% w/w | 0.75 ± 0.03 | NaClO 2 mol L−1 | 0.75 ± 0.03 |

| P3-Ultrasil 0.5% w/w | 0.71 ± 0.02 | NaClO 1 mol L−1 | 0.77 ± 0.03 |

| P3-Ultrasil 0.1% w/w | 0.66 ± 0.02 | NaClO 0.5 mol L−1 | 0.72 ± 0.04 |

| Membrane unused | 0.83 ± 0.01 |

| Regeneration Mechanism | Findings |

|---|---|

| Mechanical backwashing | With a backwashing pressure of 0.2 bar, the filtration performance can be increased by 350% after 10 cycles. A further increase in the backwashing pressure does increase the filtration performance, but not in proportion to the applied pressure increase. |

| Cleaning through hydrolysis | Acids (HCl; H3NSO3) and alkalis (NaOH) with a hydrolytic effect do not have a cleaning effect. This indicates that fouling behavior is not caused by mineral or easily soluble organic residues. The main cause of the increase in filter resistance is therefore the biofilm, which consists of poorly soluble fats and oils. |

| Cleaning through hydrolysis and surfactants | Both the pure NaClO and the multi-component mixture P3-Ultrasil regenerate the membrane to 5.4 times the throughput compared to that without cleaning. The oxidative effect of NaClO and the dissolving effect of the anionic surfactants in P3-Ultrasil can thus remove the biofilm on the membrane. However, larger cell residues are not removed with these two cleaning agents. |

| Enzymatic cleaning | Enzymatic additives can increase the flow rate by 61% compared to filtration with the industrial cleaning agent P3-Ultrasil with an identical mass concentration, even at short exposure times of 5 s and at room temperature. Higher temperatures when using enzymes do not result in a further increase in the flow rate. Since the drum filter is a dead-end filtration system and the particles are the valuable product, there is no remixing of the enzymes used with the initial suspension. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bächle, V.; Gleiß, M.; Nirschl, H. Characterization of the Regenerative Capacity of Membranes in the Presence of Fouling by Microalgae Using Detergents. Membranes 2026, 16, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010007

Bächle V, Gleiß M, Nirschl H. Characterization of the Regenerative Capacity of Membranes in the Presence of Fouling by Microalgae Using Detergents. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleBächle, Volker, Marco Gleiß, and Hermann Nirschl. 2026. "Characterization of the Regenerative Capacity of Membranes in the Presence of Fouling by Microalgae Using Detergents" Membranes 16, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010007

APA StyleBächle, V., Gleiß, M., & Nirschl, H. (2026). Characterization of the Regenerative Capacity of Membranes in the Presence of Fouling by Microalgae Using Detergents. Membranes, 16(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010007