Visualizing the Effect of Process Pause on Virus Entrapment During Constant Flux Virus Filtration

Abstract

1. Introduction

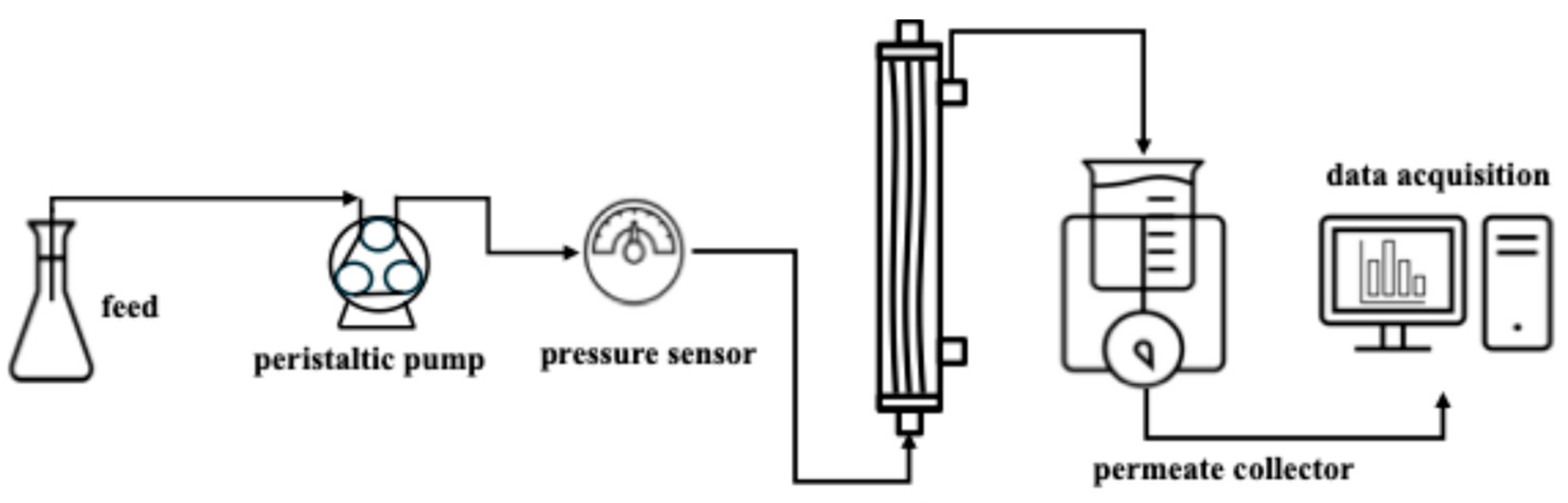

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. MVM Production and Titer Determination

2.4. MVM Labeling

2.5. MVM Detection Using Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy (LSCM)

3. Results

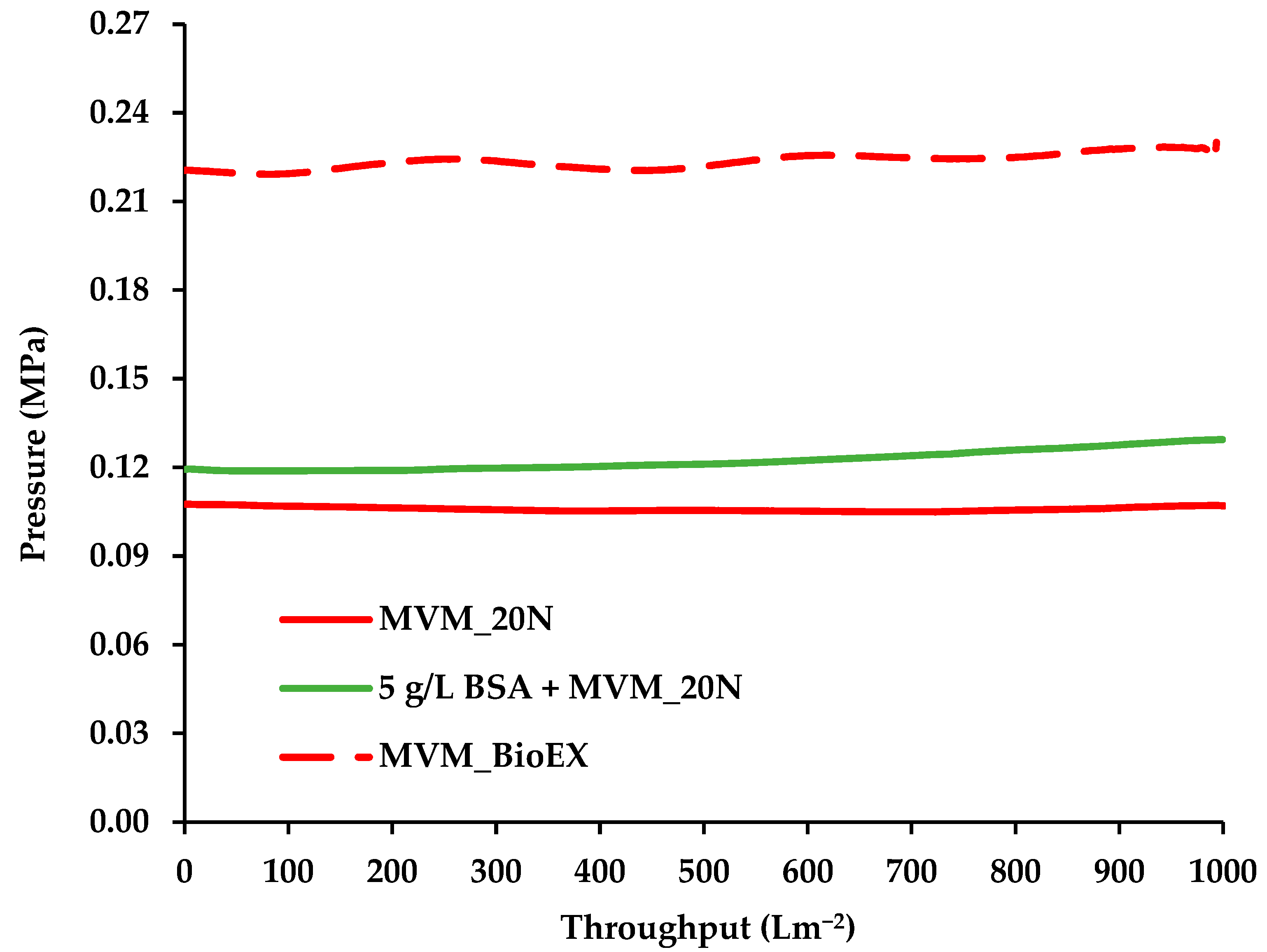

3.1. Permeate Flux

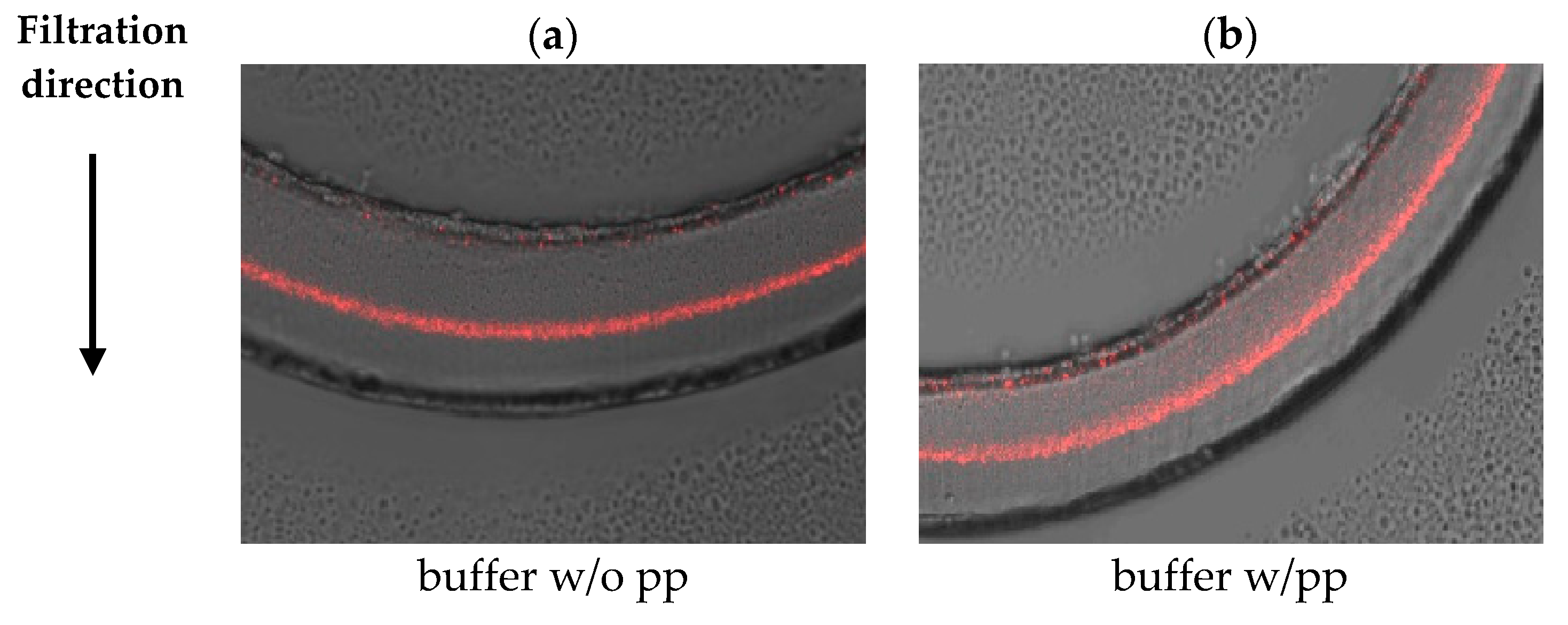

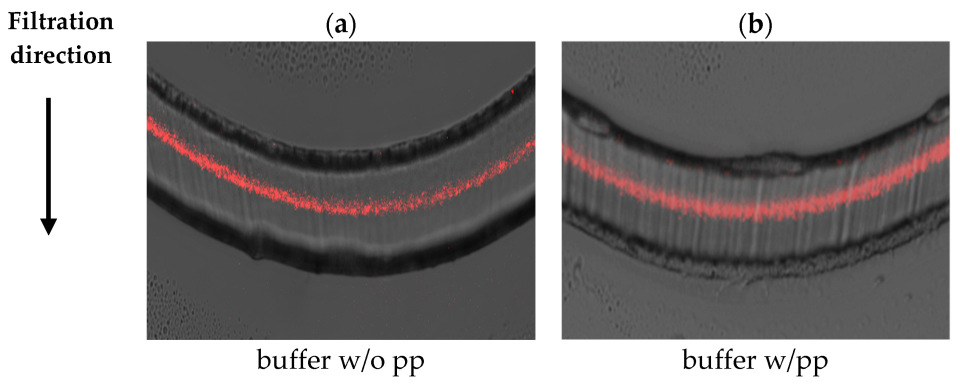

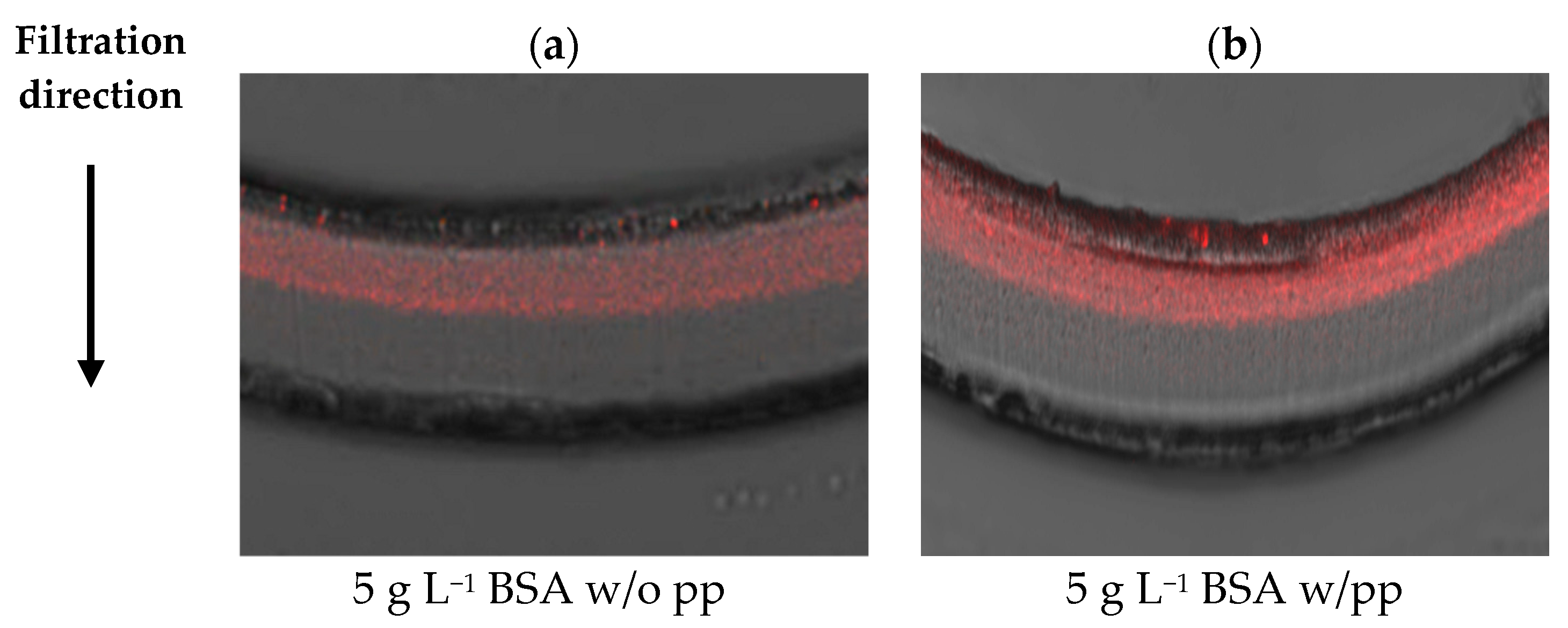

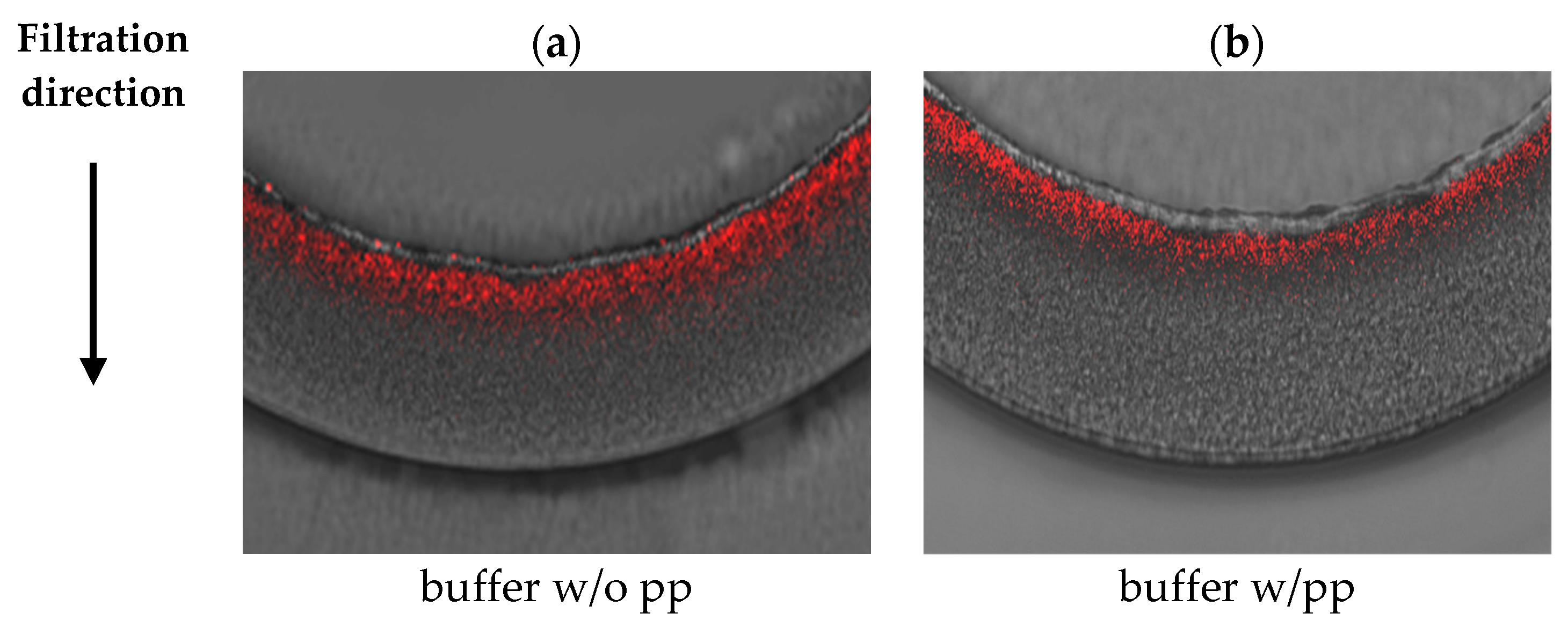

3.2. Visualization of Virus Capture

3.3. Virus Clearance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 5 g/L BSA | Planova™ S20N | Planova™ 20N |

|---|---|---|

| w/o process pause | 99.8% ± 0.08 | 99.7% ± 0.08 |

| w/process pause | 99.5% ± 0.01 | 99.5% ± 0.02 |

References

- Johnson, S.A.; Chen, S.; Bolton, G.; Chen, Q.; Lute, S.; Fisher, J.; Brorson, K. Virus filtration: A review of current and future practices in bioprocessing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydney, A.L. New developments in membranes for bioprocessing–A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 620, 118804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckey, J.; Strauss, D.; Venkiteshwaran, A.; Gao, J.; Luo, W.; Quertinmont, M.; O’Donnell, S.; Chen, D. A novel approach to achieving modular retrovirus clearance for a parvovirus filter. Biotechnol. Prog. 2014, 30, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, A.; Berting, A.; Medek, C.; Poelsler, G.; Kreil, T.R. The evolution of down-scale virus filtration equipment for virus clearance studies. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2015, 112, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, D.; Jin, H.; Park, H.; Lee, C.; Cho, Y.H.; Baek, Y. Effect of protein fouling on filtrate flux and virus breakthrough behaviors during virus filtration process. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2023, 120, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, Y.; Singh, N.; Arunkumar, A.; Zydney, A.L. Effects of histidine and sucrose on the biophysical properties of a monoclonal antibody. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateu, M.G. Mechanical properties of viruses analyzed by atomic force microscopy: A virological perspective. Virus Res. 2012, 168, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billups, M.; Minervini, M.; Holstein, M.; Feroz, H.; Ranjan, S.; Hung, J.; Bao, H.; Li, Z.J.; Ghose, S.; Zydney, A.L. Role of membrane structure on the filtrate flux during monoclonal antibody filtration through virus retentive membranes. Biotechnol. Prog. 2022, 38, e3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Murakami, S.; Futamura, A.; Watanabe, N.; Masuda, Y. A design space for the filtration of challenging monoclonal antibodies using Planova™ S20N, a new regenerated cellulose virus removal filter. Biotechnol. Prog. 2025, 41, e3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, D.; Kim, M.; Lee, C.; Baek, Y. Virus filtration in biopharmaceutical downstream processes: Key factors and current limitations. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2024, 53, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCasse, D.; Genest, P.; Pizzelli, K.; Greenhalgh, P.; Mullin, L.; Slocum, A. Impact of process interruption on virus retention of small-virus filters. BioProcess Int. 2013, 11, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kosiol, P.; Kahrs, C.; Thom, V.; Ulbricht, M.; Hansmann, B. Investigation of virus retention by size exclusion membranes under different flow regimes. Biotechnol. Prog. 2019, 35, e2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Namila, F.; Sansongko, D.; Wickramasinghe, S.R.; Jin, M.; Kanani, D.; Qian, X. The effects of flux on the clearance of minute virus of mice during constant flux virus filtration. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 3511–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, M.A.; Zydney, A.L. Effects of a pressure release on virus retention with the Ultipor DV20 membrane. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 111, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, N.B.; Bakhshayeshi, M.; Zydney, A.L.; Mehta, A.; van Reis, R.; Kuriyel, R. Internal virus polarization model for virus retention by the Ultipor® VF Grade DV20 membrane. Biotechnol. Prog. 2014, 30, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaCasse, D.; Lute, S.; Fiadeiro, M.; Basha, J.; Stork, M.; Brorson, K.; Godavarti, R.; Gallo, C. Mechanistic failure mode investigation and resolution of parvovirus retentive filters. Biotechnol. Prog. 2016, 32, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.A.; Zydney, A.L. Effect of filtrate flux and process disruptions on virus retention by a relatively homogeneous virus removal membrane. Biotechnol. Prog. 2022, 38, e3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peles, J.; Cacace, B.; Carbrello, C.; Giglia, S.; Hersey, J.; Zydney, A.L. Virus retention during constant-flux virus filtration using the Viresolve® Pro membrane including process disruption effects. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 709, 123059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Qian, X.; Shirataki, H.; Strauss, D.; Wickramasinghe, R. The effects of membrane structure and filtration conditions on virus filtration. J. Membr. Sci. 2026, 737, 124781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisi, R.; Widmer, E.; Gooch, B.; Roth, N.J.; Ros, C. Mechanistic insights into flow-dependent virus retention in different nanofilter membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 636, 119548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, T.; Popp, B.; Roth, N.J. Choice of parvovirus model for validation studies influences the interpretation of the effectiveness of a virus filtration step. Biologicals 2019, 60, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisi, R.; Bieri, J.; Roth, N.J.; Ros, C. Determination of parvovirus retention profiles in virus filter membranes using laser scanning microscopy. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 603, 118012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahi Kasei Bioprocess Inc. Filtration Procedure Planova™ BioEX Filters. 2024. Available online: https://planova.ak-bio.com/products_services/planova-bioex/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Asher, D.R.; Katz, A.B.; Khan, N.Z.; Mehta, U. Methods of Producing High Titer, High Purity Virus Stocks and Methods of Use Thereof. US9644187B2, 9 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-T.; Xu, W.; Cai, K.; Ferreira, G.; Wickramasinghe, S.R.; Qian, X. Factors affecting robustness of anion exchange chromatography: Selective retention of minute virus of mice using membrane media. J. Chromatogr. B 2022, 1210, 123449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, R.; Harris, R. Techniques in Experimental Virology; Harris, R.J.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1964; Volume 169. [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, H.R.; Shieh, L.; Klibanov, A.M.; Langer, R. Heterogeneity of serum albumin samples with respect to solid-state aggregation via thiol-disulfide interchange—Implications for sustained release from polymers. J. Control. Release 1997, 44, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namila, F.; Zhang, D.; Traylor, S.; Nguyen, T.; Singh, N.; Wickramasinghe, R.; Qian, X. The effects of buffer condition on the fouling behavior of MVM virus filtration of an Fc-fusion protein. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 2621–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishari, S.K.; Venkiteshwaran, A.; Zydney, A.L. Probing effects of pressure release on virus capture during virus filtration using confocal microscopy. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2015, 112, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G.; Cabatingan, M.; Rubino, M.; Lute, S.; Brorson, K.; Bailey, M. Normal-flow virus filtration: Detection and assessment of the endpoint in bioprocessing. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2005, 42, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.Z.; Parrella, J.J.; Genest, P.W.; Colman, M.S. Filter preconditioning enables representative scaled-down modelling of filter capacity and viral clearance by mitigating the impact of virus spike impurities. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2009, 52, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongo-Hirasaki, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yanagida, K.; Okuyama, K. Removal of small viruses (parvovirus) from IgG solution by virus removal filter Planova® 20N. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 278, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Virus Filter | Filter Area (cm2) | Maximum Operating Pressure (MPa) | Membrane Polymer | Feed Volume (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planova™ S20N | 10 | 0.216 | Cuprammonium regenerated cellulose | 1000 |

| Planova™ 20N | 10 | 0.098 | Cuprammonium regenerated cellulose | 1000 |

| Planova™ BioEX | 3.0 | 0.343 | Hydrophilized polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) | 300 |

| Virus Filter | Flux Measurements | Log Removal of Virus (LRV) | LSCM Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20N | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled and non labeled), data presented without process pause | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause |

| 5 g L−1 BSA spiked with MVM (labeled and non labeled), data presented without process pause | 5 g L−1 BSA spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause | 5 g L−1 BSA spiked with, MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause | |

| 20N | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented without process pause | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause |

| 5 g L−1 BSA spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause | 5 g L−1 BSA spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause | 5 g L−1 BSA spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause | |

| BioEX | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented without process pause | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause | Buffer spiked with MVM (labeled), data presented with and without process pause |

| Feed Stream | Monomer (%) | Dimer (%) | Trimer (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSA (5 g L−1, PBS buffer) | 84.9 | 13.2 | 1.9 |

| MVM | Planova™ S20N | Planova™ 20N | Planova™ BioEX | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed (logTCID50 mL−1) | LRV | Feed (logTCID50 mL−1) | LRV | Feed (logTCID50 mL−1) | LRV | |

| w/pp | 5.17 | ≥5.54 ± 0.11 | 5.01 | 4.69 ± 0.13 | 4.83 | ≥5.21 ± 0.11 |

| w/o pp | 4.92 | ≥5.29 ± 0.13 | 5.00 | 4.69 ± 0.13 | 4.75 | ≥5.13 ± 0.14 |

| 5 g L−1 BSA with MVM | Planova™ S20N | Planova™ 20N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feed Titer (logTCID50 mL−1) | LRV | Feed Titer (logTCID50 mL−1) | LRV | |

| w/pp | 4.83 | ≥5.20 ± 0.11 | 4.83 | 4.45 ± 0.13 |

| w/o pp | 4.83 | ≥5.20 ± 0.11 | 4.92 | 4.57 ± 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, W.; Qian, X.; Shirataki, H.; Straus, D.; Wickramasinghe, S.R. Visualizing the Effect of Process Pause on Virus Entrapment During Constant Flux Virus Filtration. Membranes 2026, 16, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010006

Xu W, Qian X, Shirataki H, Straus D, Wickramasinghe SR. Visualizing the Effect of Process Pause on Virus Entrapment During Constant Flux Virus Filtration. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Wenbo, Xianghong Qian, Hironobu Shirataki, Daniel Straus, and Sumith Ranil Wickramasinghe. 2026. "Visualizing the Effect of Process Pause on Virus Entrapment During Constant Flux Virus Filtration" Membranes 16, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010006

APA StyleXu, W., Qian, X., Shirataki, H., Straus, D., & Wickramasinghe, S. R. (2026). Visualizing the Effect of Process Pause on Virus Entrapment During Constant Flux Virus Filtration. Membranes, 16(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010006