Effects of Lipopolysaccharides from Hafnia alvei PCM1200, Proteus penneri 12, and Proteus vulgaris 9/57 on Liposomal Membranes Composed of Natural Egg Yolk Lecithin (EYL) and Synthetic DPPC: An EPR Study and Computer Simulations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. LPS Preparation

2.2. Lecithin and Spin Probes

2.3. EPR Measurements

2.4. Computer-Based Model

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. EPR Experiment

3.1.1. Rotational Correlation Time Analysis

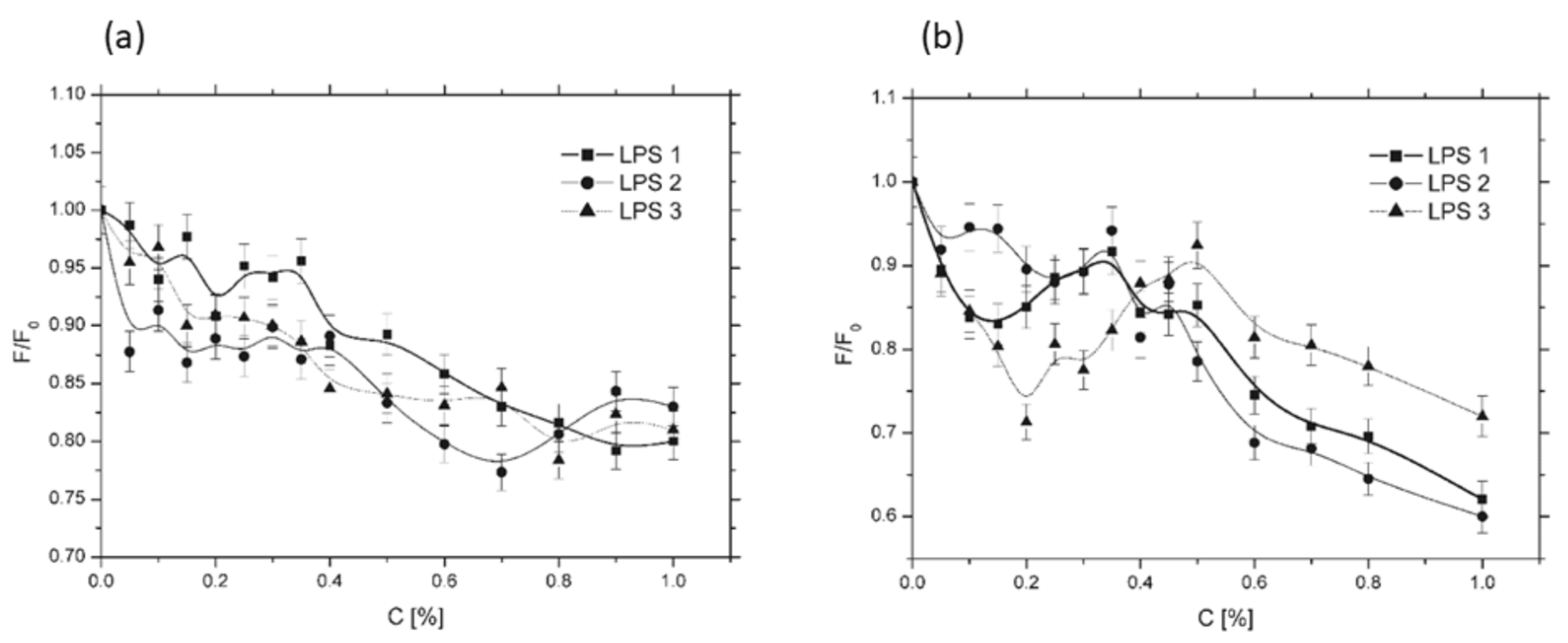

3.1.2. Partition Coefficient Analysis

3.2. Simulation Results

3.2.1. Bitmap Analysis

3.2.2. Binding Energy Dependence on Dopant Concentration

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Subczynski, W.K.; Raguz, M.; Widomska, J. Multilamellar Liposomes as a Model for Biological Membranes: Saturation Recovery EPR Spin Labeling Studies. Membranes 2022, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, D.; Pytel, B. Effect of Ionic and Nonionic Compounds Structure on the Fluidity of Model Lipid Membranes: Computer Simulation and EPR Experiment. Membranes 2024, 14, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Su, J.; Qin, L.; Zhang, X.; Mao, S. Exploring the Influence of Inhaled Liposome Membrane Fluidity on Its Interaction with Pulmonary Physiological Barriers. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 6786–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, J.M.; Yamazaki, M. Spontaneous Insertion of Lipopolysaccharide into Lipid Membranes from Aqueous Solution. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2011, 164, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, M.F.; Sanchez, S.; Bakás, L. Visualization and Analysis of LPS Distribution in Binary Phospholipid Bilayers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 383, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, I.J. Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides Change Membrane Fluidity with Relevance to Phospholipid and Amyloid Beta Dynamics in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Microb. Biochem. Technol. 2016, 8, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowicz-Rudy, J.; Wałęsa, R. The Improvement of the Therapeutic Index of Biologically Active Substances—Intelligent Drug Carriers Tend to Be Liposomes. Curr. Top. Biophys. 2013, 36, 19–58. [Google Scholar]

- Szulc, A.; Johannes, K.; Carolyn, V.; Sebastian, F.; Sandro, K. Preparation of Ready-to-Use Small Unilamellar Phospholipid Vesicles by Ultrasonication with a Beaker Resonator. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2015, 27, 256–263. [Google Scholar]

- Woodbury, D.J.; Richardson, E.S.; Grigg, A.W.; Welling, R.D.; Knudson, B.H. Reducing Liposome Size with Ultrasound: Bimodal Size Distributions. J. Liposome Res. 2006, 16, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-S.; Hwangbo, S.-A.; Jeong, Y.-G. Preparation of Uniform Nano Liposomes Using Focused Ultrasonic Technology. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Sustainable Liposome Production: Ultrasonication Reduces Size and Polydispersity. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 11234–11246. [Google Scholar]

- Świerzko, A.; Łukasiewicz, J.; Cedzyński, M.; Maciejewska, A.; Jachymek, W.; Niedziela, T.; Matsushita, M.; Lugowski, C. New Functional Ligands for Ficolin 3 among Lipopolysaccharides of Hafnia alvei (PCM 1200 and Others). Glycobiology 2012, 22, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Jeong, M.S.; Kang, J.; Rhee, J.-K.; Kwon, J.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, J.-S.; Choi, H.-J.; et al. Complete Genome Sequence of a Commensal Bacterium, Hafnia alvei CBA7124, Isolated from Human Feces. Gut Pathog. 2017, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, J.M.; Abbott, S.L. The Genus Hafnia: From Soup to Nuts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishore, J. Isolation, Identification & Characterization of Proteus penneri—A Missed Rare Pathogen. Indian J. Med. Res. 2012, 135, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- Kaca, W.; Lindner, B.; Radziejewska-Lebrecht, J. Classification of Proteus penneri Lipopolysaccharides into Core Region Serotypes. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2016, 205, 505–518. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. Proteus. In Molecular Detection of Human Bacterial Pathogens; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, N. Proteus Species in Various Clinical Specimens: P. vulgaris, P. penneri and Others. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Chakkour, M.; Hammoud, Z.; Farhat El Roz, A.; Ezzeddine, Z.; Ghssein, G. Overview of Proteus mirabilis pathogenicity and virulence. Insights into the role of metals. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1383618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzewiecka, D. Significance and Roles of Proteus spp. Bacteria in Natural Environments. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 72, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Duša, F.; Witos, J.; Ruokonen, S.K.; Wiedmer, S.K. Determination of the Main Phase Transition Temperature of Phospholipids by Nanoplasmonic Sensing. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, S.J.; Choi, Y.; Leonenko, Z. Preparation of DOPC and DPPC Supported Planar Lipid Bilayers for Atomic Force Microscopy and Atomic Force Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3514–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.M. Phase Equilibria and Structure of Dry and Hydrated Egg Lecithin. J. Lipid Res. 1967, 8, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.B.; Back, J.F. Thermal Transitions in the Low-Density Lipoprotein and Lipids of the Egg Yolk of Hens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1975, 388, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, D.; Olchawa, R. Dynamics of Surface of Lipid Membranes: Theoretical Considerations and the ESR Experiment. Eur. Biophys. J. 2017, 46, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Tang, G.; Tu, Y. Water Behaviors at Lipid Bilayers/Water Interface under Various Force Fields. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.08554. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen, O.G.; Boothroyd, A.; Harris, R.; Jan, N.; Lookman, T.; MacDonald, L.; Pink, D.A.; Zuckermann, M.J. Computer Simulation of the Main Gel–Fluid Phase Transition of Lipid Bilayers. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 2027–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubica, K. Pink’s Model and Lipid Membranes. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 1997, 2, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Man, D.; Olchawa, R.; Kubica, K. Membrane Fluidity and the Surface Properties of the Lipid Bilayer: ESR Experiment and Computer Simulation. J. Liposome Res. 2010, 20, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, D.C. The Art of Molecular Dynamics Simulation; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thijssen, J.M. Computational Physics; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Subczynski, W.K.; Widomska, J. Spin-Lattice Relaxation Rates of Lipid Spin Labels as a Measure of Their Rotational Diffusion Rates in Lipid Bilayer Membranes. Membranes 2022, 12, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemminga, M.A.; Ulrich, A.S. (Eds.) Dynamics of Membrane Lipids: EPR and Related Techniques; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, D. Electron Spin Resonance in Membrane Research: Protein–Lipid Interactions from Challenging Beginnings to State of the Art. Eur. Biophys. J. 2010, 39, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, L.; Camenisch, T.G.; Hyde, J.S.; Subczynski, W.K. Saturation recovery EPR spin-labeling method for quantification of lipids in biological membrane domains. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2017, 48, 1351–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbell, W.L.; Altenbach, C. Investigation of Structure and Dynamics in Membrane Proteins Using Site-Directed Spin Labeling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1994, 4, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrink, S.J.; Corradi, V.; Souza, P.C.T.; Ingólfsson, H.I.; Tieleman, D.P.; Sansom, M.S.P. Computational Modeling of Realistic Cell Membranes. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 6184–6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, S.W.; Jakobsson, E.; Subramaniam, S. Simulation Studies of Lipid Bilayers and Membranes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1999, 9, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kastowsky, M.; Gutberlet, T.; Bradaczek, H. Molecular modelling of the three-dimensional structure and conformational flexibility of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 4798–4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, S.; Kim, D.; McIntosh, T.J. Lipopolysaccharide Bilayer Structure: Effect of Chemotype, Core Mutations, Divalent Cations, and Temperature. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 10758–10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudino, A.; Mauzerall, D. Dielectric properties of the polar head group region of zwitterionic lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 1986, 50, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, D.; Pytel, B.; Białek, M. Impact of Vanadium Complexes with Tetradentate Schiff Base Ligands on the DPPC and EYL Liposome Membranes: EPR Studies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemminga, M.A. Interpretation of ESR and Saturation Transfer ESR Spectra of Spin-Labeled Lipids and Membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1983, 32, 323–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Man, D.; Pytel, B.; Pisarek, I. Effects of Lipopolysaccharides from Hafnia alvei PCM1200, Proteus penneri 12, and Proteus vulgaris 9/57 on Liposomal Membranes Composed of Natural Egg Yolk Lecithin (EYL) and Synthetic DPPC: An EPR Study and Computer Simulations. Membranes 2026, 16, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010038

Man D, Pytel B, Pisarek I. Effects of Lipopolysaccharides from Hafnia alvei PCM1200, Proteus penneri 12, and Proteus vulgaris 9/57 on Liposomal Membranes Composed of Natural Egg Yolk Lecithin (EYL) and Synthetic DPPC: An EPR Study and Computer Simulations. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleMan, Dariusz, Barbara Pytel, and Izabella Pisarek. 2026. "Effects of Lipopolysaccharides from Hafnia alvei PCM1200, Proteus penneri 12, and Proteus vulgaris 9/57 on Liposomal Membranes Composed of Natural Egg Yolk Lecithin (EYL) and Synthetic DPPC: An EPR Study and Computer Simulations" Membranes 16, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010038

APA StyleMan, D., Pytel, B., & Pisarek, I. (2026). Effects of Lipopolysaccharides from Hafnia alvei PCM1200, Proteus penneri 12, and Proteus vulgaris 9/57 on Liposomal Membranes Composed of Natural Egg Yolk Lecithin (EYL) and Synthetic DPPC: An EPR Study and Computer Simulations. Membranes, 16(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010038