Theoretical and Experimental Studies of Permeate Fluxes in Double-Flow Direct-Contact Membrane Distillation (DCMD) Modules with Internal Recycle

Abstract

1. Introduction

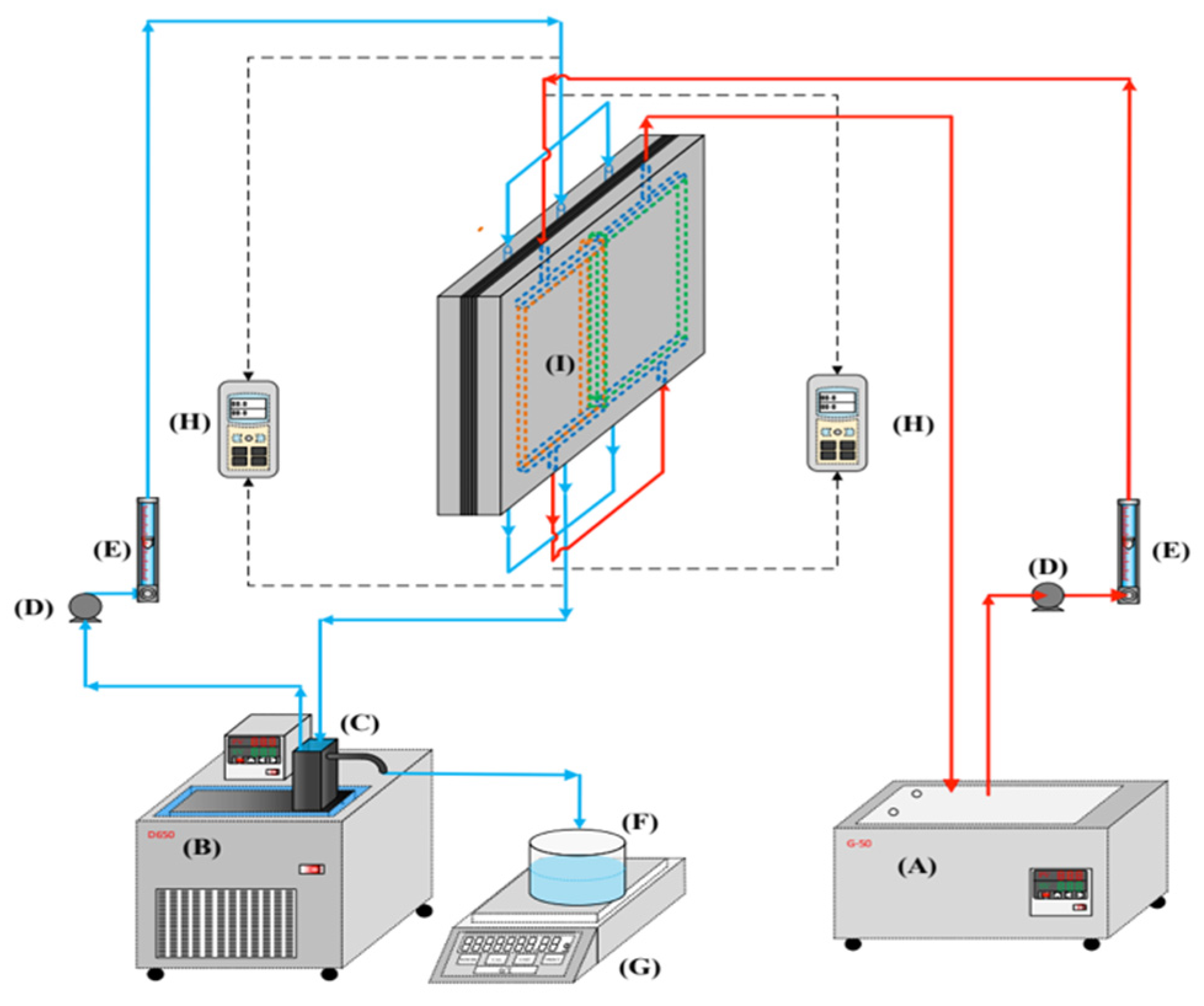

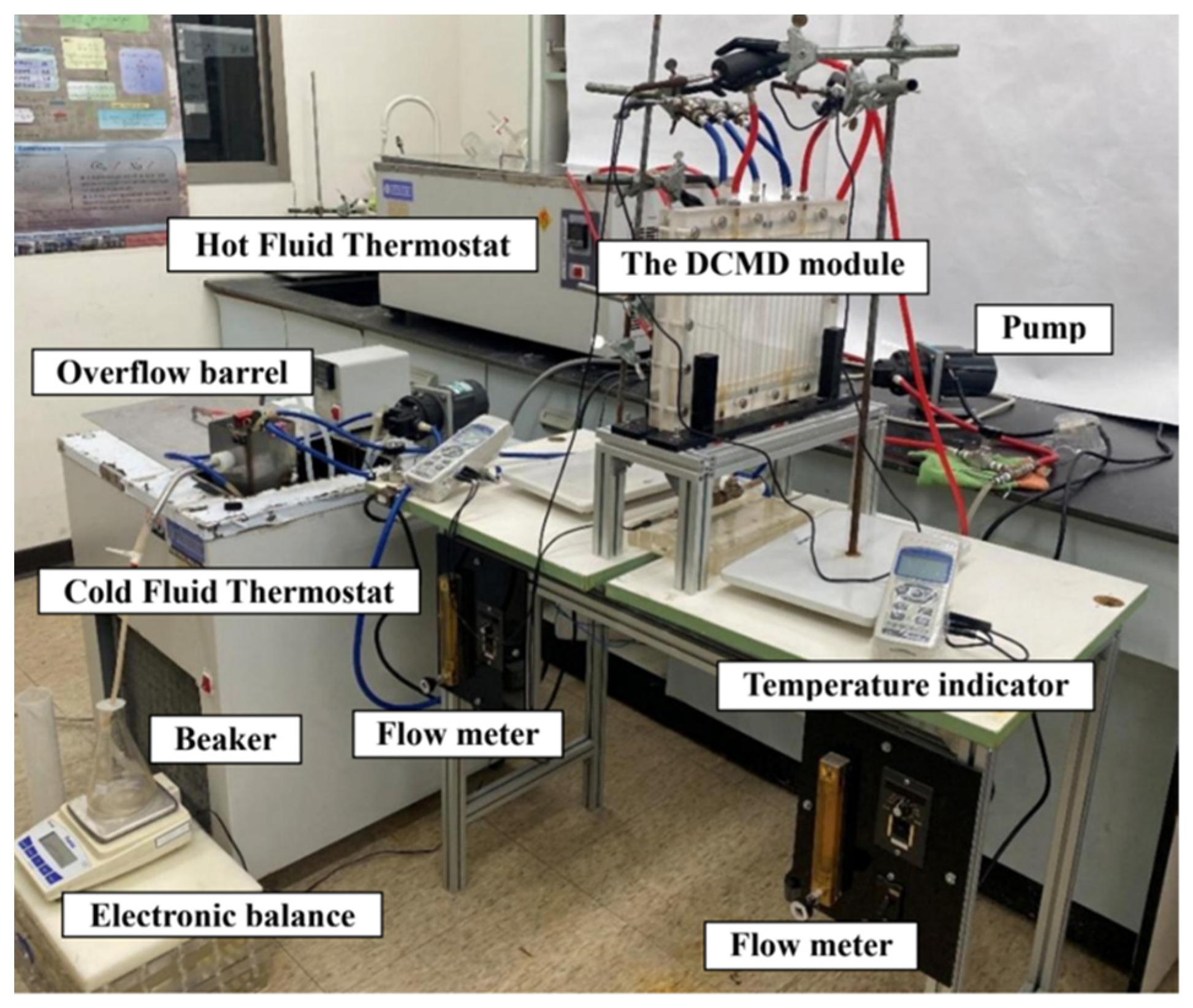

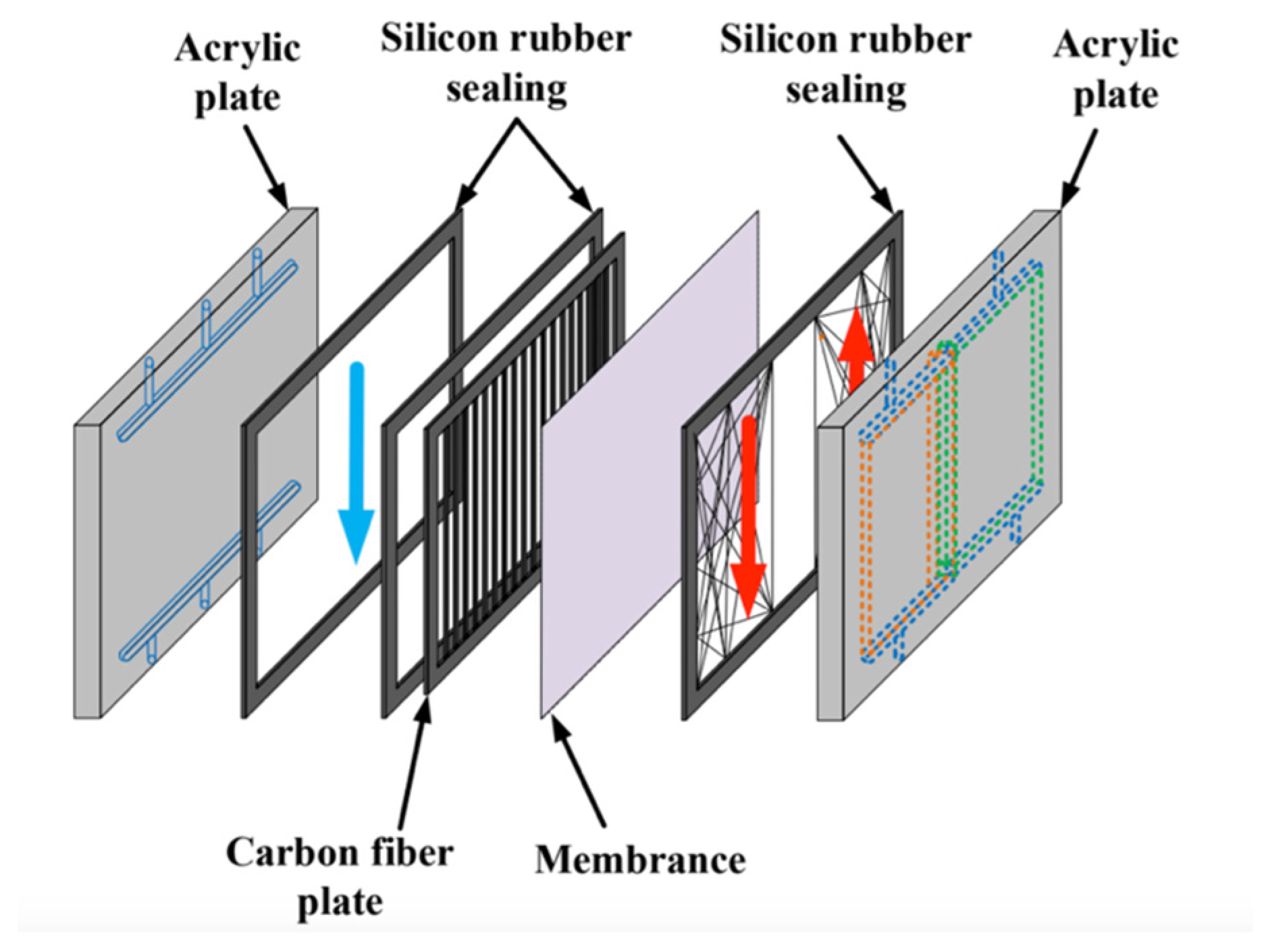

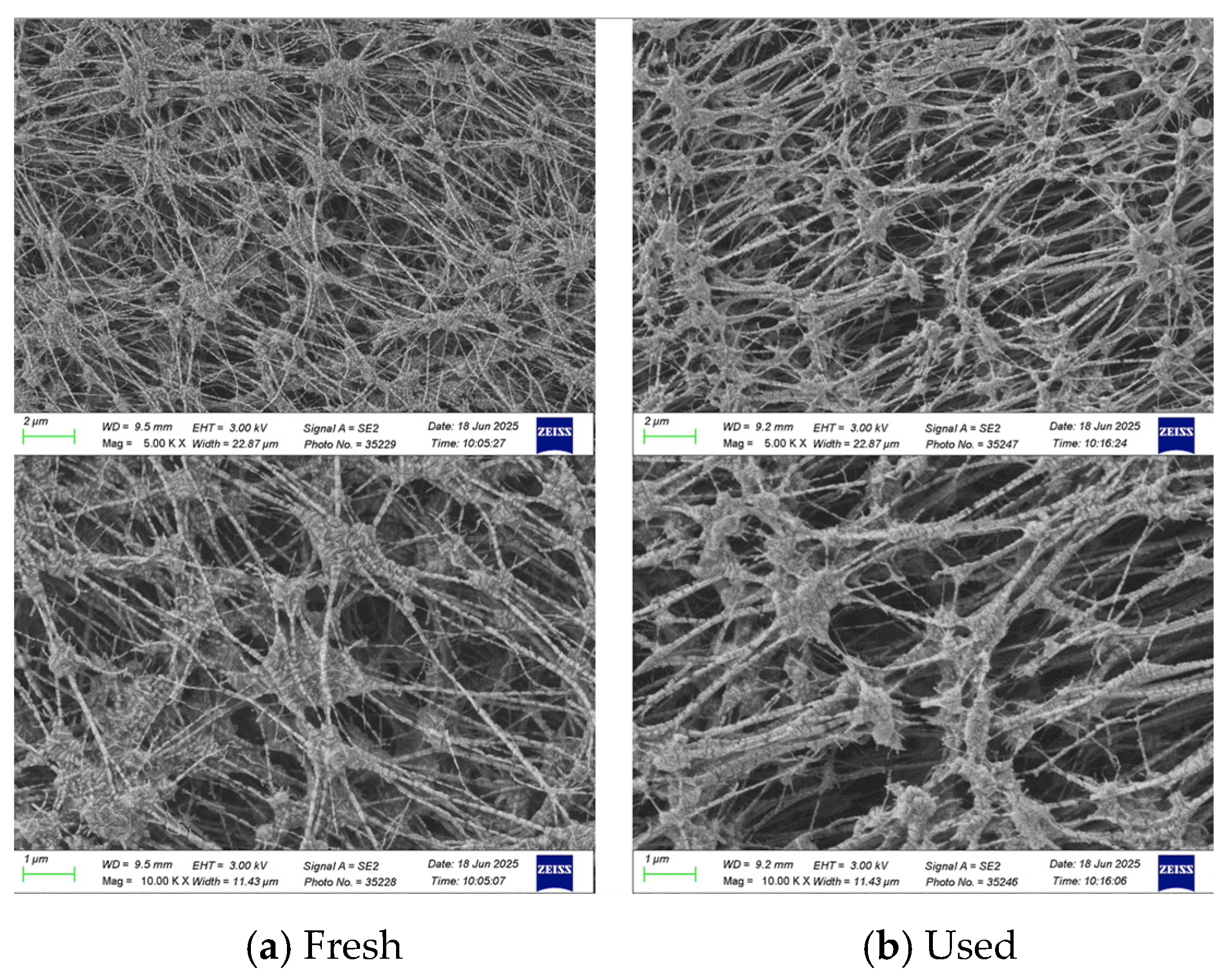

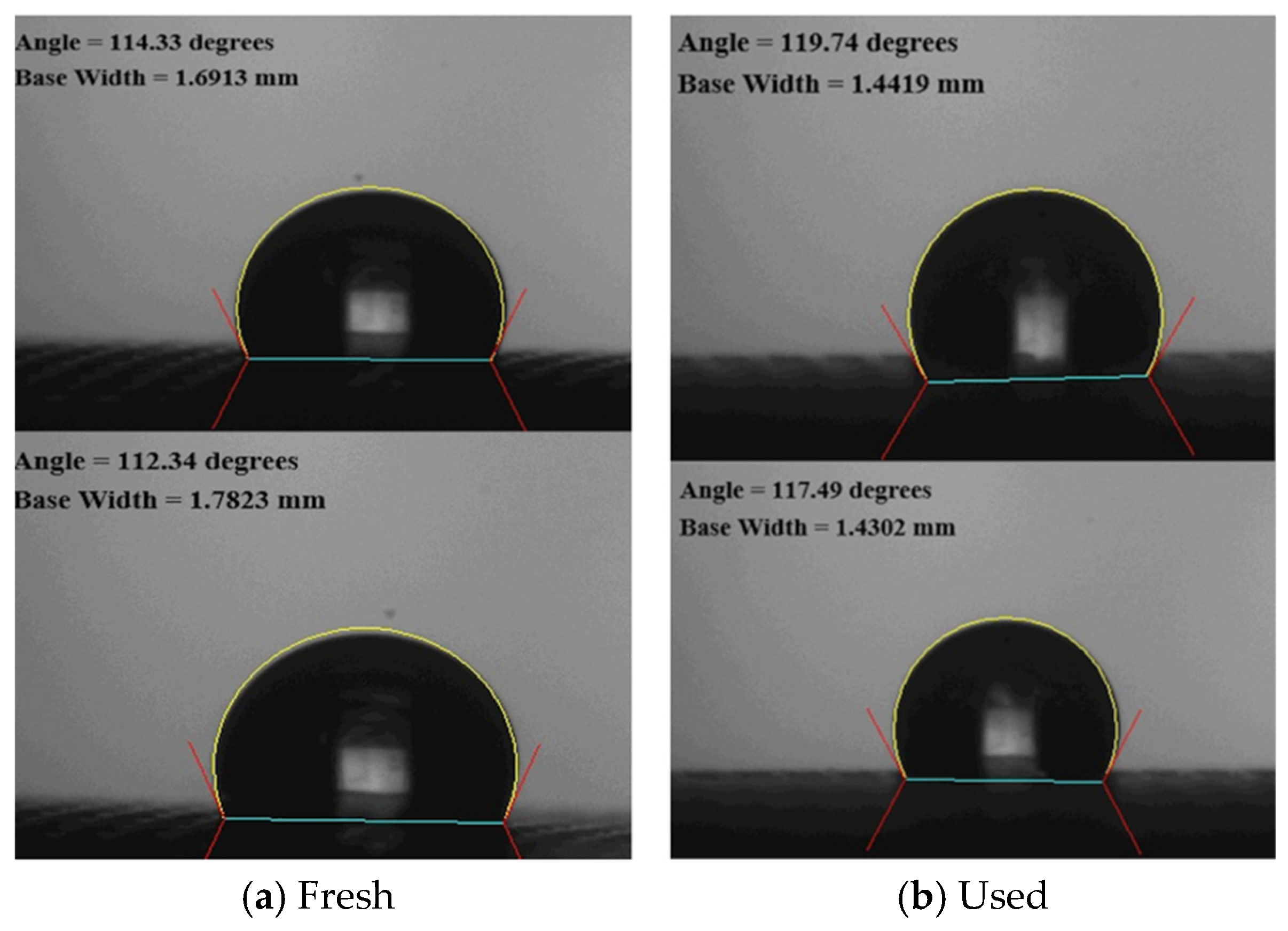

2. Membrane Distillation Apparatus and Materials

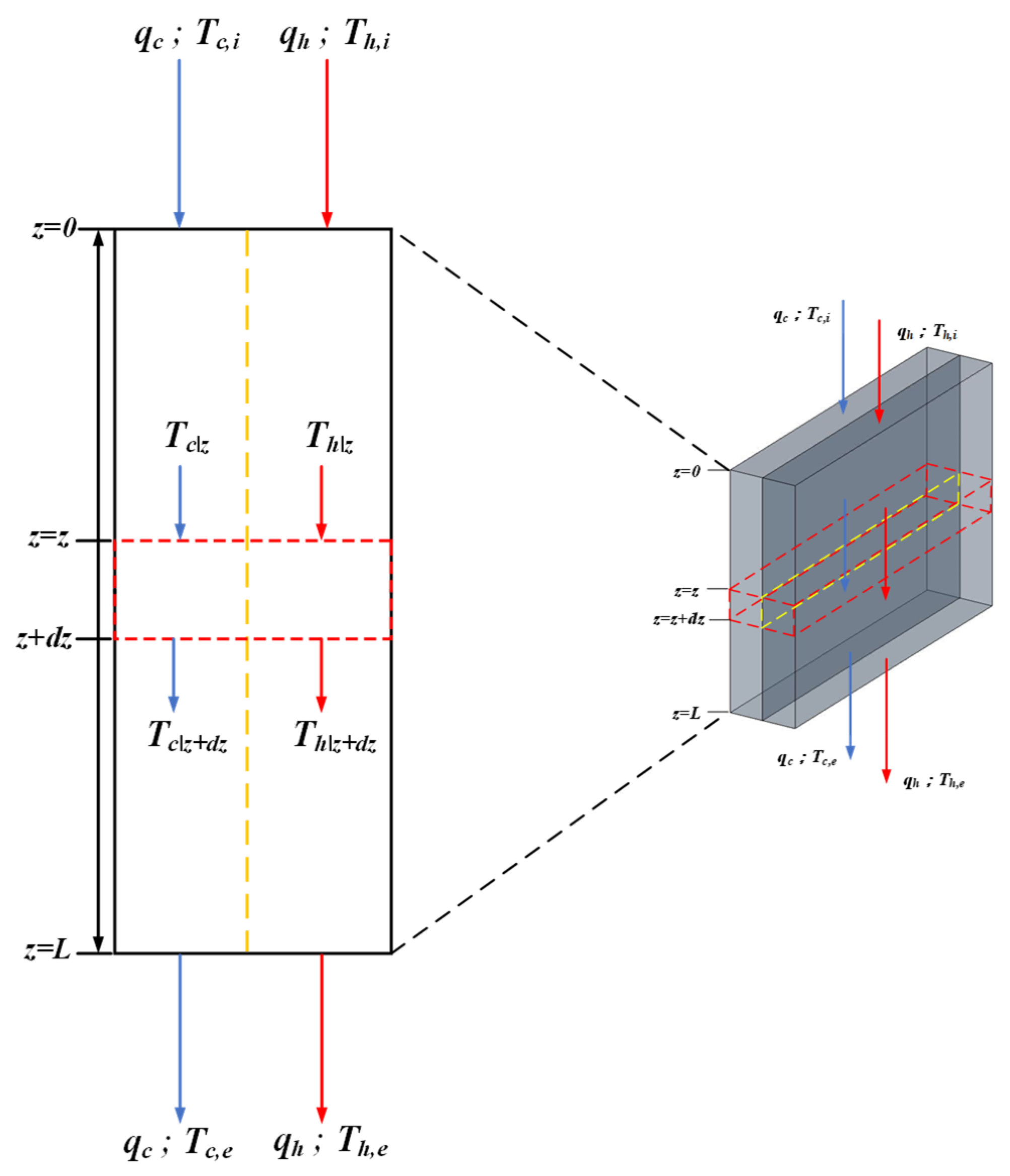

3. Mathematical Formulations

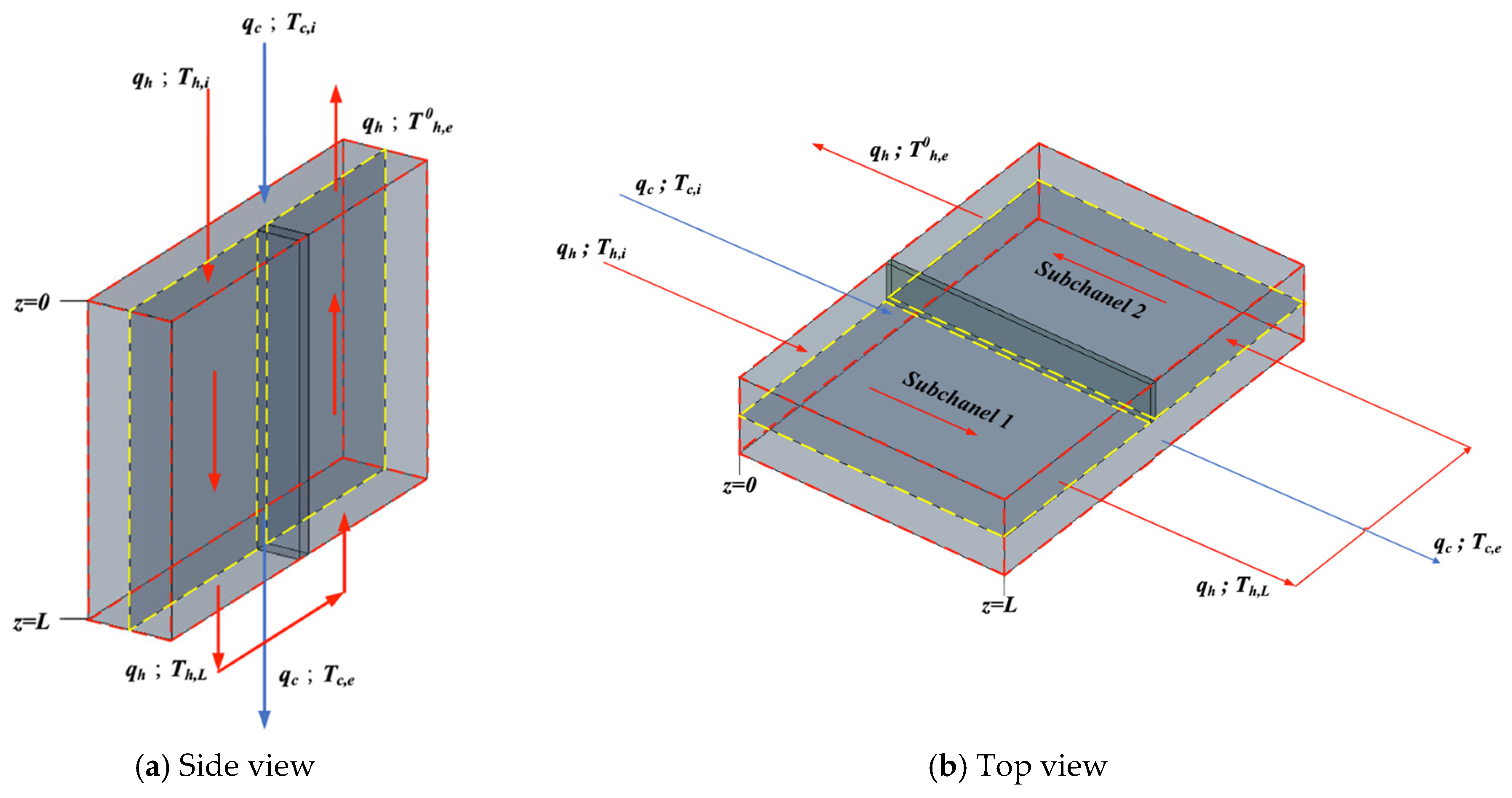

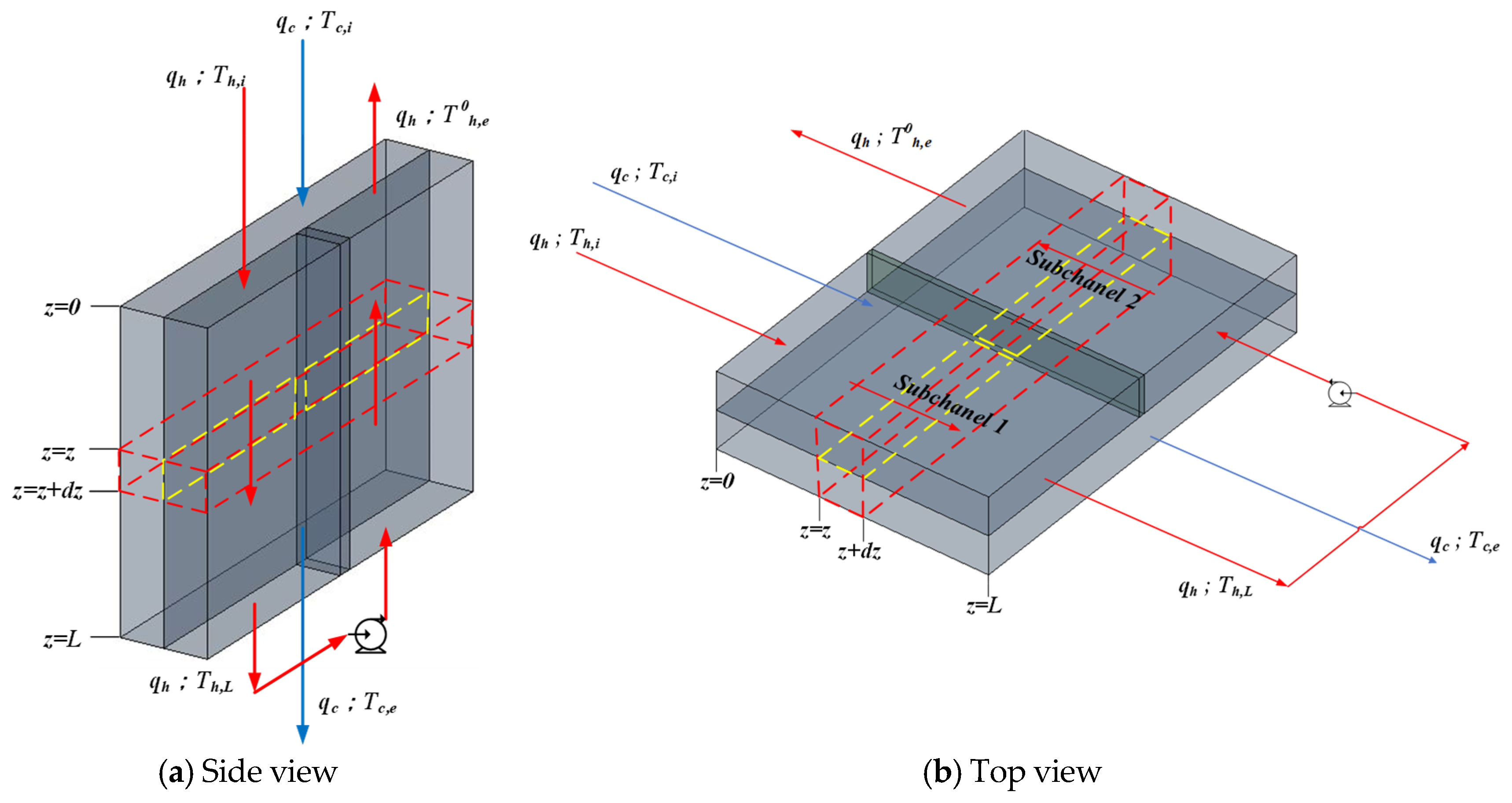

3.1. Heat and Mass Transfers

3.2. Theory and Analysis

3.3. Outlet Temperature

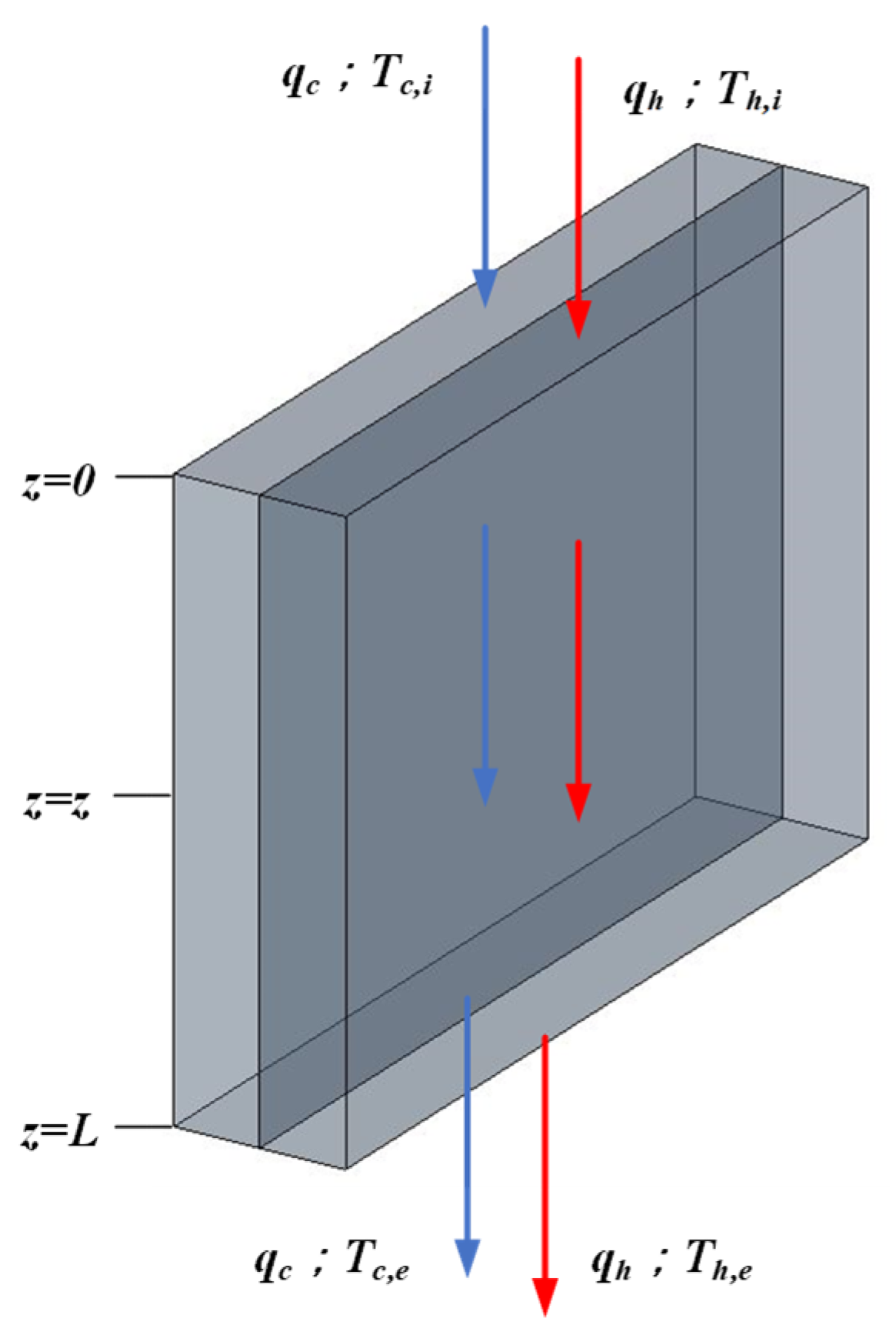

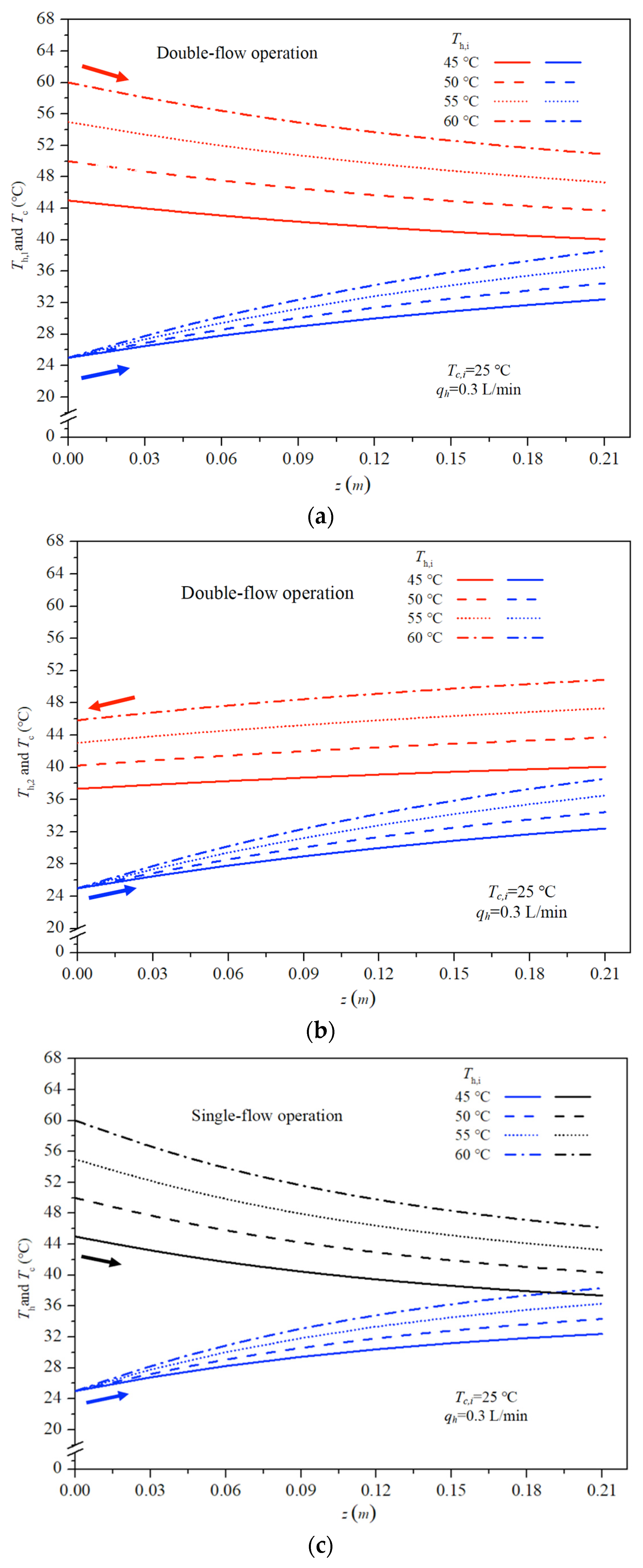

3.4. Temperature Distributions in Single-Flow Operations

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Lessening Temperature Polarization Effect by Operating Double-Flow Channels

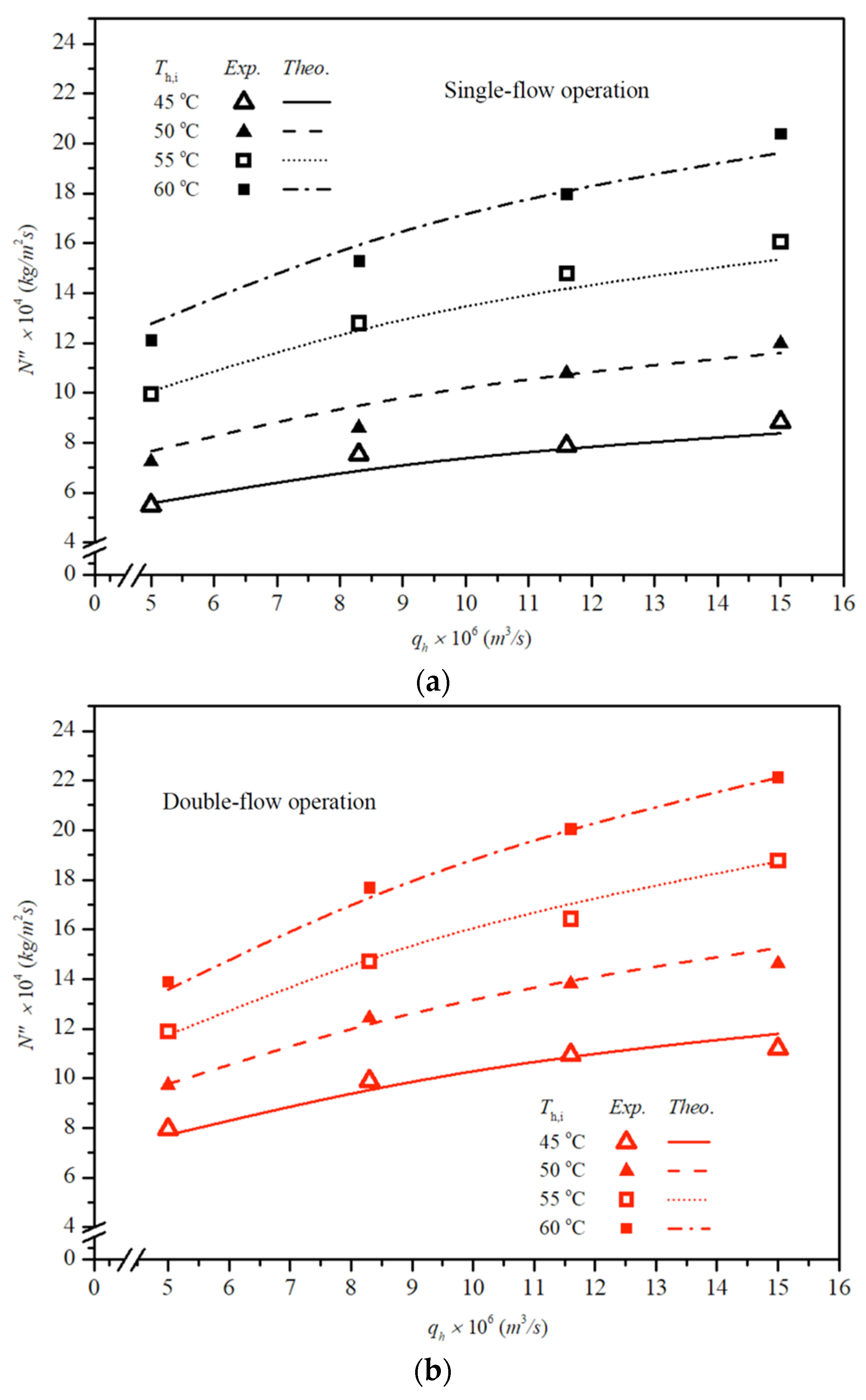

4.2. The Permeate Flux Improvement

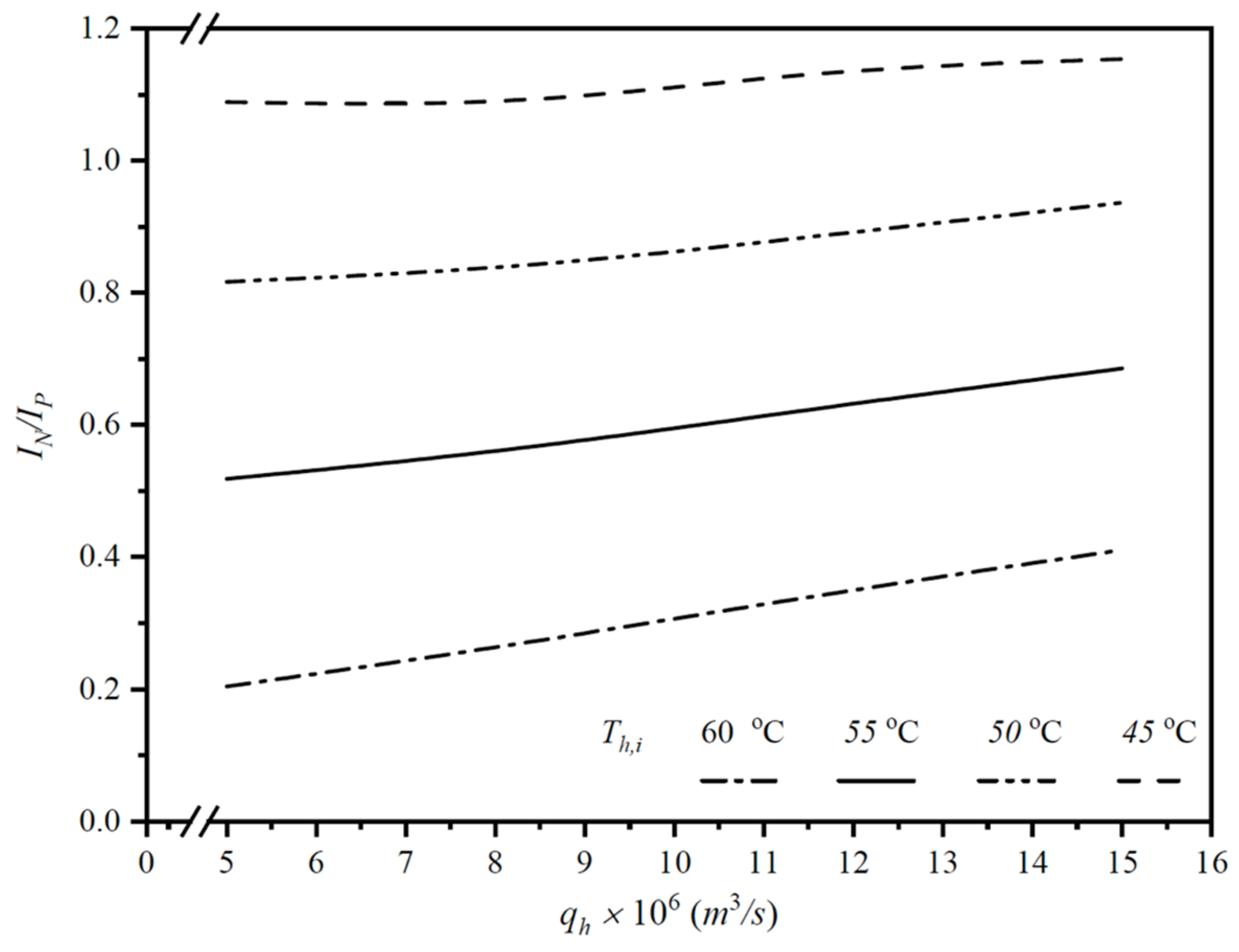

4.3. Power Consumption Increment

5. Conclusions

- Operating double-flow channels in the hot-saline feed stream yields relative increases in permeate flux, with a maximum improvement of 40.77% at an inlet hot-saline temperature of 45 °C and a 0.9 L/min hot-saline feed flow rate, compared with a single-flow channel module.

- The results demonstrate that double-flow channels in membrane-distillation modules achieve a more pronounced permeate-flux improvement due to a larger convective heat-transfer coefficient.

- The study shows higher permeate-flux improvement in modules with larger inlet hot-saline temperatures; however, the ratio for double-flow channels follows a reverse order.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Cross-sectional area of flow channel (m2) | |

| Water activity in NaCl solution | |

| Friction losses coefficient | |

| Heat capacity (), | |

| Membrane coefficient based on the Knudsen diffusion model () | |

| Membrane coefficient based on the molecular diffusion model () | |

| Membrane permeation coefficient () | |

| Channel height (m) | |

| Diffusion coefficient of air and vapor in the membrane () | |

| Hydraulic equivalent diameter of channel (m), | |

| Accuracy deviation of experimental results from the theoretical predictions | |

| Fanning friction factor for cold feed stream | |

| Fanning friction factor for hot-saline feed stream | |

| Hydraulic dissipate energy (W) | |

| Permeate flux relative factor | |

| Power consumption relative index | |

| Channel length (m) | |

| Friction loss (J kg−1), | |

| Molecular weight of water (kg mol−1) | |

| Cold feed stream with time rate of heat capacity (J K−1 s−1) | |

| Hot-saline feed stream with time rate of heat capacity (J K−1 s−1) | |

| Distillate flux () | |

| Average value of for all number of experimental measurements () | |

| Number of experimental measurements | |

| Mean saturated pressure in membrane (Pa) | |

| Saturation vapor pressure (Pa) | |

| Volumetric flow rate (m3 s−1), | |

| Heat flux () | |

| Membrane pore radius (m) | |

| Gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1) | |

| Reynolds number | |

| Uncertainty of the experimental measurements | |

| Mean value of | |

| Membrane surface temperature in the cold feed region (K) | |

| Membrane surface temperature in the hot-saline feed region (K) | |

| Mean temperature in membrane (K) | |

| Average velocity () | |

| Width of channel (m) | |

| Liquid mole fraction of water | |

| Mole fraction of NaCl in saline solution | |

| Vapor mole fraction of water | |

| Natural log mean vapor mole fraction of water in the membrane | |

| Axial coordinate along the flow direction (m) | |

| Greek letters | |

| Thickness of membrane (µm) | |

| Membrane porosity | |

| Gas viscosity () | |

| Latent heat of water () | |

| Eigenvalues | |

| Viscosity () | |

| Density () | |

| Temperature polarization coefficients | |

| Membrane tortuosity | |

| Subscripts | |

| 1 | Channel 1 of the hot-saline feed side |

| Channel 2 of the cold feed side | |

| c | Cold feed stream |

| double | Double-flow operation |

| h | Hot feed stream |

| single | Single-flow operation |

| exp | Experimental results |

| i | At the inlet |

| e | At the outlet |

| theo | Theoretical predictions |

References

- Lawson, K.W.; Lloyd, D.R. Membrane distillation. II. direct contact MD. J. Membr. Sci. 1996, 120, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehesa-Carrasco, U.; Pérez-Rábago, C.; Arancibia-Bulnes, C. Experimental evaluation and modeling of internal temperatures in an air gap membrane distillation unit. Desalination 2013, 326, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, R.; Feron, P.; Jansen, A. Membrane contactor applications. Desalination 2008, 224, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Darwish, N.; Hilal, N. Membrane distillation: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2012, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alklaibi, A.M.; Lior, N. Membrane-distillation desalination: Status and potential. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 171, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, S.O.; Camacho, L.M. Heat and Mass Transport in Modeling Membrane Distillation Configuration: A Review. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Diez, L.; Vázquez-González, M.I. Effects of polarization on mass transport through hydrophobic porous membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 4128–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.; Ahmad, H.; Antar, M.; Laoui, T.; Khayet, M. Experimental and theoretical investigations on water desalination using direct contact membrane distillation. Desalination 2017, 404, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sirkar, K.K. Studies in vacuum membrane distillation with flat membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 523, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidari, A.H.; Heijman, S.G.J.; van der Meer, W.G.J. Visualization of hydraulic conditions inside the feed channel of reverse osmosis: A practical comparison of velocity between empty and spacer–filled channel. Water Res. 2016, 106, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Santander, I.D.; Gómez-Espinosa, R.M.; García-Bórquez, A.; Torrestiana-Sánchez, B. Enhancement of Heat and Mass Transfer in the DCMD Process Using UV-Assisted 1-Hexene-Grafted PP Membranes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 44903−44911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.P.; Deng, L.B.; Huang, H.Y.; Zhou, J.L.; Liao, Y.Y.; Qiu, L.; Yang, H.T.; Yao, L. Janus Photothermal Membrane as an Energy Generator and a Mass-Transfer Accelerator for High-Efficiency Solar-Driven Membrane Distillation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 26861−26869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taamneh, Y.; Bataineh, K. Improving the performance of direct contact membrane distillation utilizing spacer-filled channel. Desalination 2017, 408, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Hsu, J.A.; Chang, C.L.; Ho, C.D.; Cheng, T.W. Simulation study of transfer characteristics for spacer-filled membrane distillation desalination modules. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 2045–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.D.; Chen, L.; Chen, L.; Huang, M.C.; Lai, J.Y.; Chen, Y.A. Distillate flux enhancement in the air gap membrane distillation with inserting carbon-fiber spacers. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 2815–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Gusnawan, P.; Zhang, G.Y.; Yu, J.J. Novel Janus composite hollow fiber membrane-based direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD) process for produced water desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 597, 117756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Luo, A.Q.; Fu, S.L.; Wang, Y.R.; Hou, K.X.; Ma, J.; Hu, L.F.; Cheng, N.; Tang, X.B.; Liang, H. Insights into the enhanced flux and robust desalination of hydrogel composite Janus membrane in membrane distillation: Overlooked interfacial compatibility. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 171425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakaib, M.; Hasani, S.M.F.; Mahmood, M. CFD modeling for flow and mass transfer in spacer-obstructed membrane feed channels. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 326, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Shirazi, M.M.A.; Nthunya, L.; Castro-Mũnoz, R.; Ismail, N.; Tavajohi, N.; Zaragoza, G.; Quist-Jensen, C.A. Progress in module design for membrane distillation. Desalination 2024, 581, 117584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.C.; Cooper, P.; Nelemans, B.; Cath, T.Y.; Nghiem, L.D. Optimising thermal efficiency of direct contact membrane distillation by brine recycling for small-scale seawater desalination. Desalination 2015, 374, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhami, M.; Alkhatib, A.; Albaba, M.T.; Ayari, M.A.; Altaee, A.; AL-Ejji, M.; Das, P.; Hawari, A.H. Modeling of flat sheet-based direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD) for the robust prediction of permeate flux using single and ensemble interpretable machine learning. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnam, P.; Shafieian, A.; Zargar, M.; Khiadani, M. Development of machine learning and stepwise mechanistic models for performance prediction of direct contact membrane distillation module—A comparative study. Chem. Eng. Process. 2022, 173, 108857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Gilron, J.; Sirkar, K.K. High water recovery in direct contact membrane distillation using a series of cascades. Desalination 2013, 323, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.G. Liquid circulation in a drift-tube bubble column. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1985, 40, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.M.; Tsai, S.W.; Chiang, C.L. Recycle effects on heat and mass transfer through a parallel-plate channel. AIChE J. 1987, 33, 1743–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadian, M.A.; Zhang, H.Y. An exact solution of extended Graetz problem with axial heat conduction. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1989, 32, 1709–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.D.; Yeh, H.M.; Sheu, W.S. An analytical study of heat and mass transfer through a parallel-plate channel with recycle. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1998, 41, 2589–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, H.M.; Ho, C.D.; Sheu, W.S. Double-pass heat or mass transfer through a parallel-plate channel with recycle. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2000, 43, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, R. Circulation of high-viscosity Newtonian and non-Newtonian liquids in jet loop reactor. Int. Chem. Eng. 1981, 21, 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, M.H.; Merchuk, J.C.; Schugerl, K. Air-lift reactor analysis: Interrelationships between riser, downcomer, and gas-liquid separator behavior, including gas recirculation effects. AIChE J. 1986, 32, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyahara, T.; Hamaguchi, M.; Sukeda, Y.; Takahashi, T. Size of bubbles and liquid circulation in a bubble column with a draught tube and sieve plate. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1986, 64, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welty, J.R.; Wick, C.E.; Wilson, R.E. Fundamentals of Momentum, Heat, and Mass Transfer, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, S.B.; Bhatia, V.K.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Jonsson, G. Characterization of microporous membranes for use in membrane contactors. J. Membr. Sci. 1997, 130, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Gary, H.; Li, J.D. Modeling heat and mass transfers in DCMD using compressible membranes. I. Knudsen-Poiseuille transition. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 387–388, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, R.J. Describing the uncertainties in experimental results. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 1988, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakac, S.; Shah, R.K.; Aung, W. Handbook of Single-Phase Convective Heat Transfer; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

(°C) | Single-Flow Operations | Double-Flow Operations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(kg m−2 s−1) | (kg m−2 s−1) | (%) | (kg m−2 s−1) | (kg m−2 s−1) | (%) | (%) | ||

| 45 | 0.3 | 5.50 | 5.57 | 1.32 | 7.95 | 7.71 | 3.13 | 38.42 |

| 0.5 | 7.53 | 6.97 | 8.12 | 9.90 | 9.63 | 2.83 | 38.21 | |

| 0.7 | 7.87 | 7.80 | 0.92 | 10.94 | 10.94 | 0.07 | 40.24 | |

| 0.9 | 8.83 | 8.37 | 5.48 | 11.20 | 11.79 | 4.95 | 40.77 | |

| 50 | 0.3 | 7.24 | 7.66 | 5.57 | 9.73 | 9.77 | 0.40 | 27.47 |

| 0.5 | 8.60 | 9.62 | 10.54 | 12.43 | 12.32 | 0.88 | 28.15 | |

| 0.7 | 10.80 | 10.79 | 0.08 | 13.81 | 14.00 | 1.41 | 29.81 | |

| 0.9 | 11.98 | 11.60 | 3.31 | 14.62 | 15.25 | 4.15 | 31.50 | |

| 55 | 0.3 | 9.96 | 10.06 | 1.06 | 11.89 | 11.74 | 1.25 | 16.69 |

| 0.5 | 12.79 | 12.68 | 0.89 | 14.71 | 14.97 | 1.78 | 18.10 | |

| 0.7 | 14.79 | 14.25 | 3.76 | 16.42 | 17.12 | 4.10 | 20.14 | |

| 0.9 | 16.07 | 15.35 | 4.68 | 18.78 | 18.74 | 0.26 | 22.07 | |

| 60 | 0.3 | 12.12 | 12.77 | 5.06 | 13.89 | 13.58 | 2.28 | 6.32 |

| 0.5 | 15.29 | 16.15 | 5.32 | 17.68 | 17.49 | 1.10 | 8.29 | |

| 0.7 | 17.98 | 18.20 | 1.20 | 20.03 | 20.13 | 0.46 | 10.62 | |

| 0.9 | 20.39 | 19.62 | 3.94 | 22.13 | 22.12 | 0.07 | 12.72 | |

(°C) | (L/min) | (K/W) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Flow | Double Flow | ||

| 45 | 0.3 | 2.28 | 2.20 |

| 0.5 | 2.24 | 2.11 | |

| 0.7 | 2.19 | 2.03 | |

| 0.9 | 2.15 | 1.96 | |

| 50 | 0.3 | 2.27 | 2.18 |

| 0.5 | 2.22 | 2.10 | |

| 0.7 | 2.17 | 2.01 | |

| 0.9 | 2.13 | 1.94 | |

| 55 | 0.3 | 2.25 | 2.16 |

| 0.5 | 2.20 | 2.08 | |

| 0.7 | 2.16 | 2.00 | |

| 0.9 | 2.11 | 1.93 | |

| 60 | 0.3 | 2.23 | 2.15 |

| 0.5 | 2.19 | 2.06 | |

| 0.7 | 2.14 | 1.99 | |

| 0.9 | 2.10 | 1.92 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ho, C.-D.; Li, C.-Y.; Chew, T.L.; Lin, Y.-T. Theoretical and Experimental Studies of Permeate Fluxes in Double-Flow Direct-Contact Membrane Distillation (DCMD) Modules with Internal Recycle. Membranes 2026, 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010037

Ho C-D, Li C-Y, Chew TL, Lin Y-T. Theoretical and Experimental Studies of Permeate Fluxes in Double-Flow Direct-Contact Membrane Distillation (DCMD) Modules with Internal Recycle. Membranes. 2026; 16(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Chii-Dong, Ching-Yu Li, Thiam Leng Chew, and Yi-Ting Lin. 2026. "Theoretical and Experimental Studies of Permeate Fluxes in Double-Flow Direct-Contact Membrane Distillation (DCMD) Modules with Internal Recycle" Membranes 16, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010037

APA StyleHo, C.-D., Li, C.-Y., Chew, T. L., & Lin, Y.-T. (2026). Theoretical and Experimental Studies of Permeate Fluxes in Double-Flow Direct-Contact Membrane Distillation (DCMD) Modules with Internal Recycle. Membranes, 16(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16010037