Polysulfone/Graphene Oxide Mixed Matrix Membranes for Improved CO2/CH4 Separation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Synthesis of Graphene Oxide

2.2.2. Mixed Matrix Membrane Fabrication

2.3. Membrane Characterization

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDX)

2.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.4. Gas Permeation Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SEM Analysis

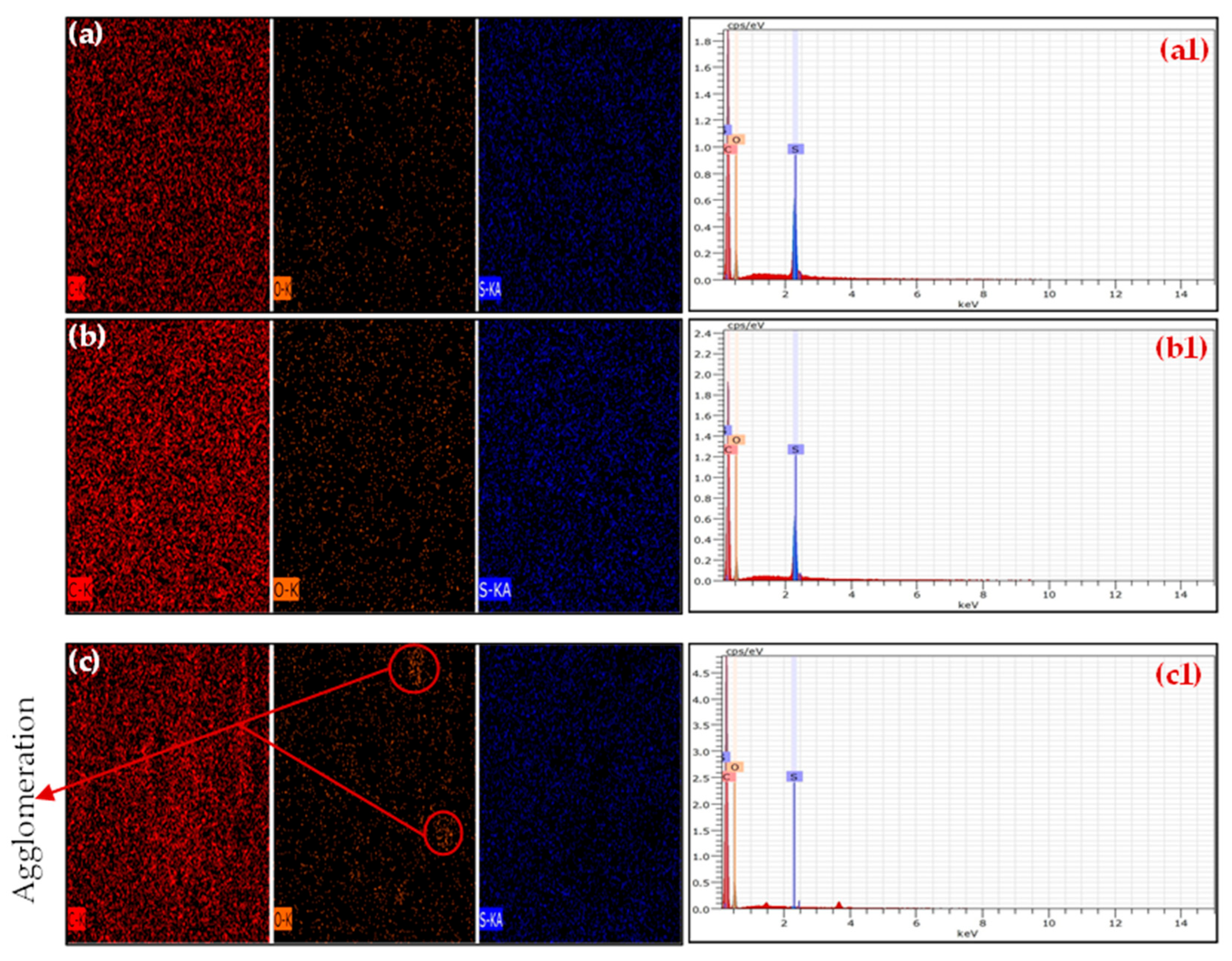

3.2. Elemental and EDX Analysis

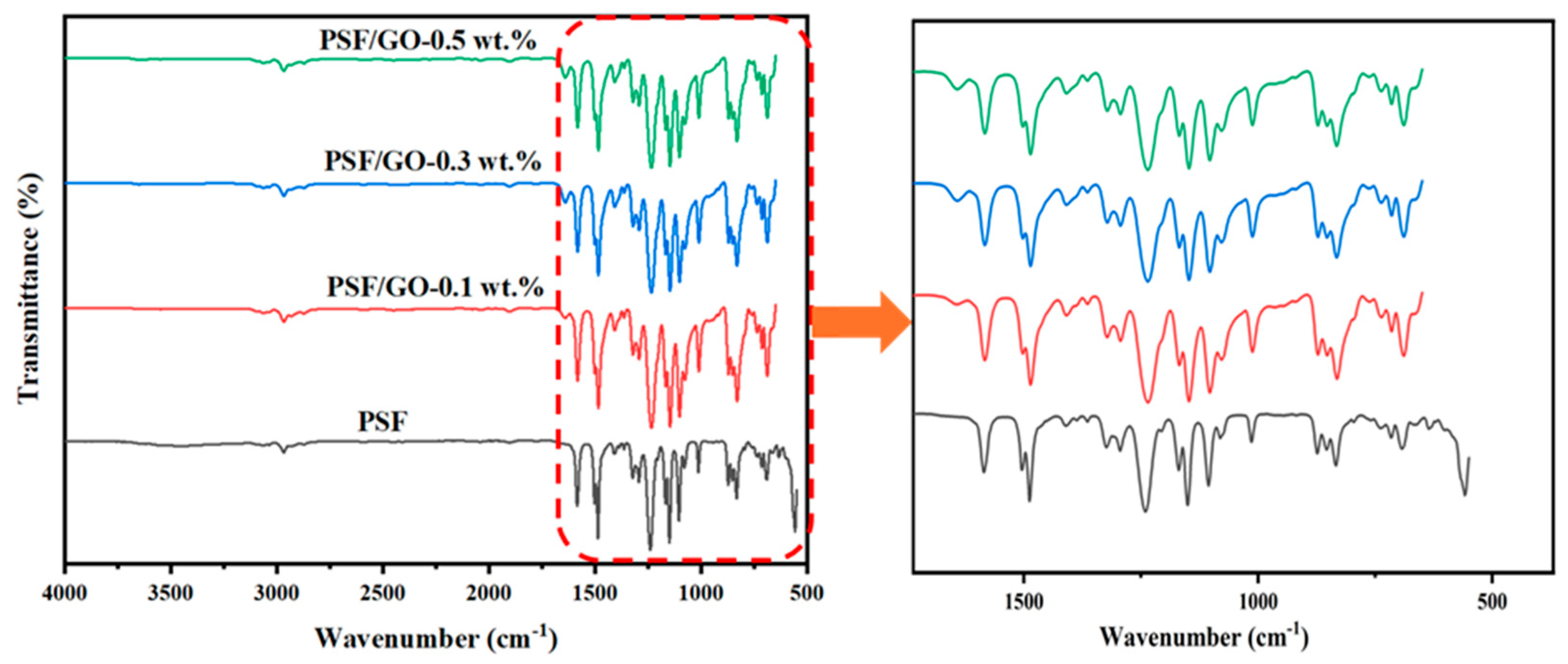

3.3. FTIR Analysis

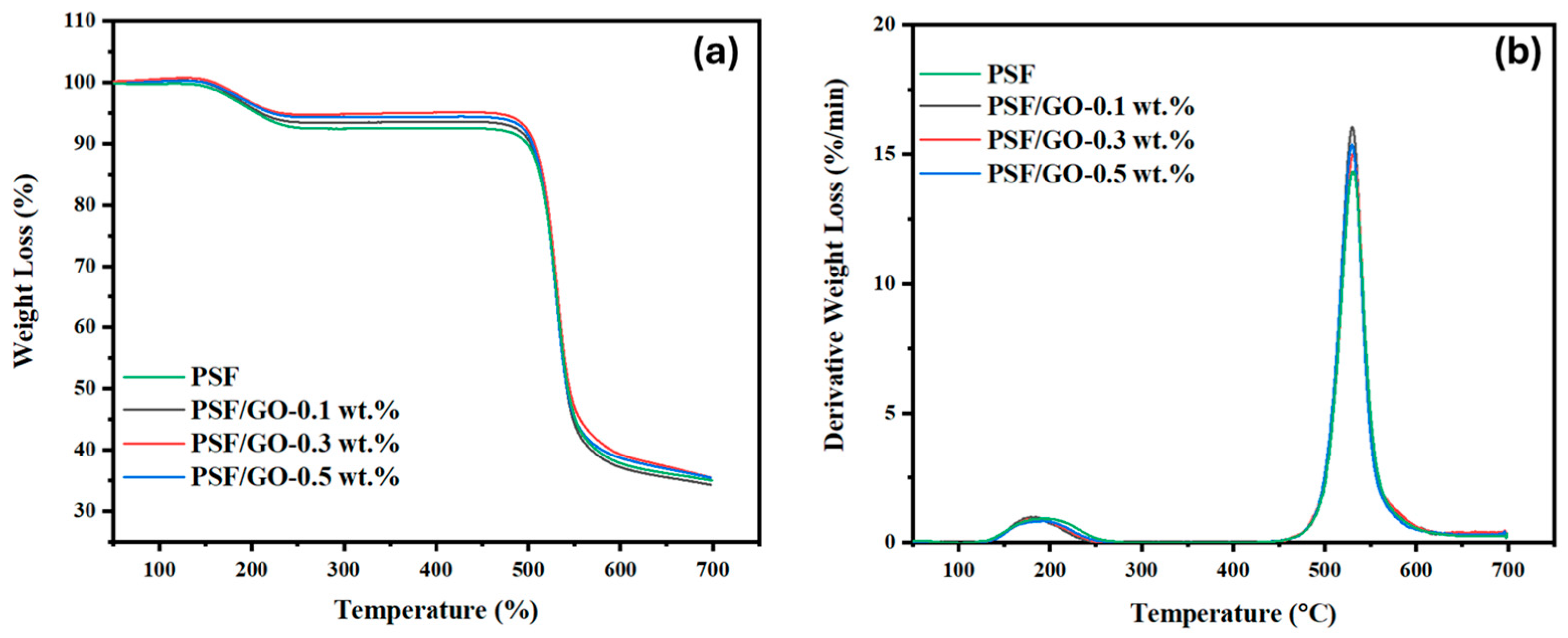

3.4. TGA

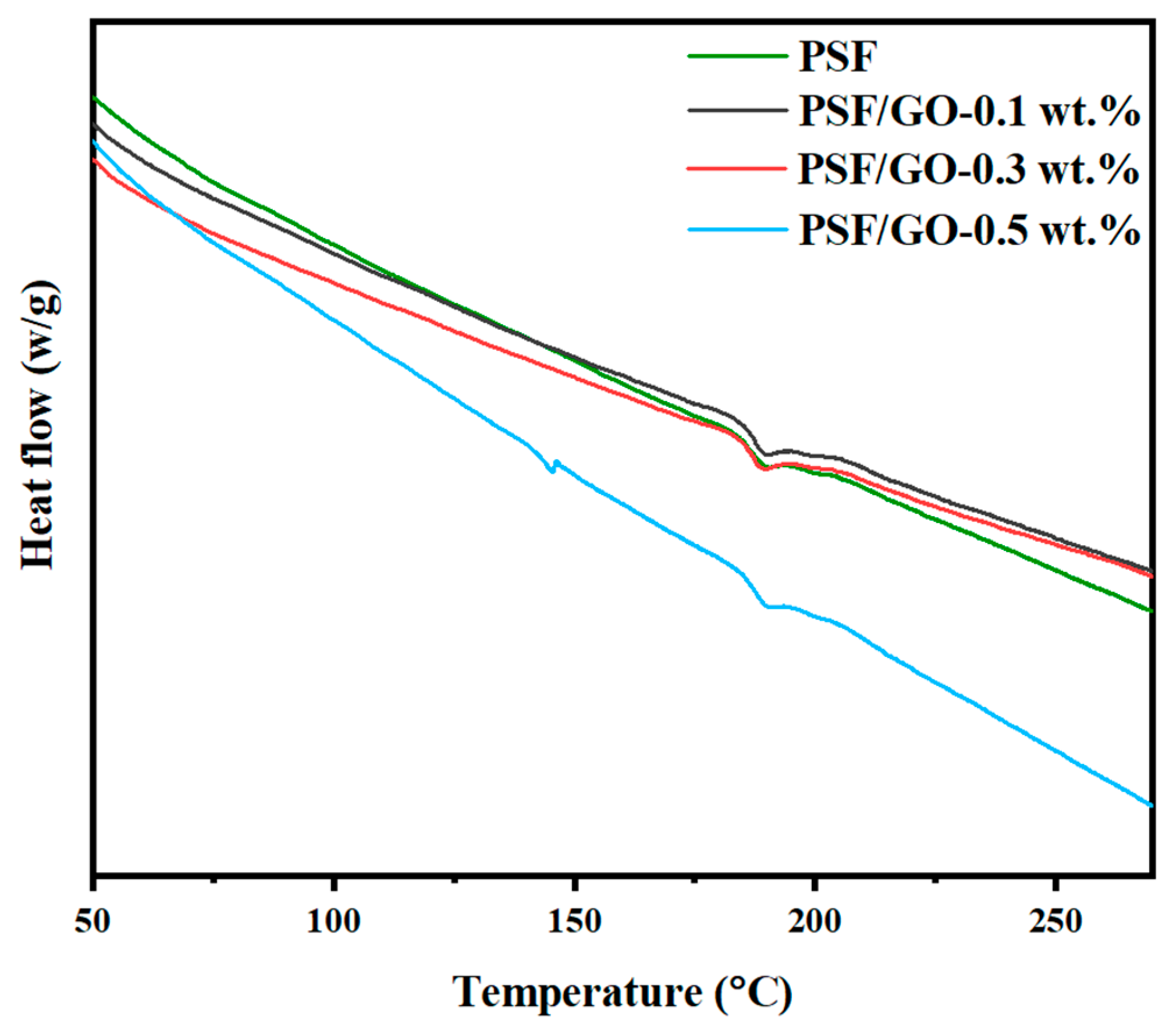

3.5. DSC Analysis

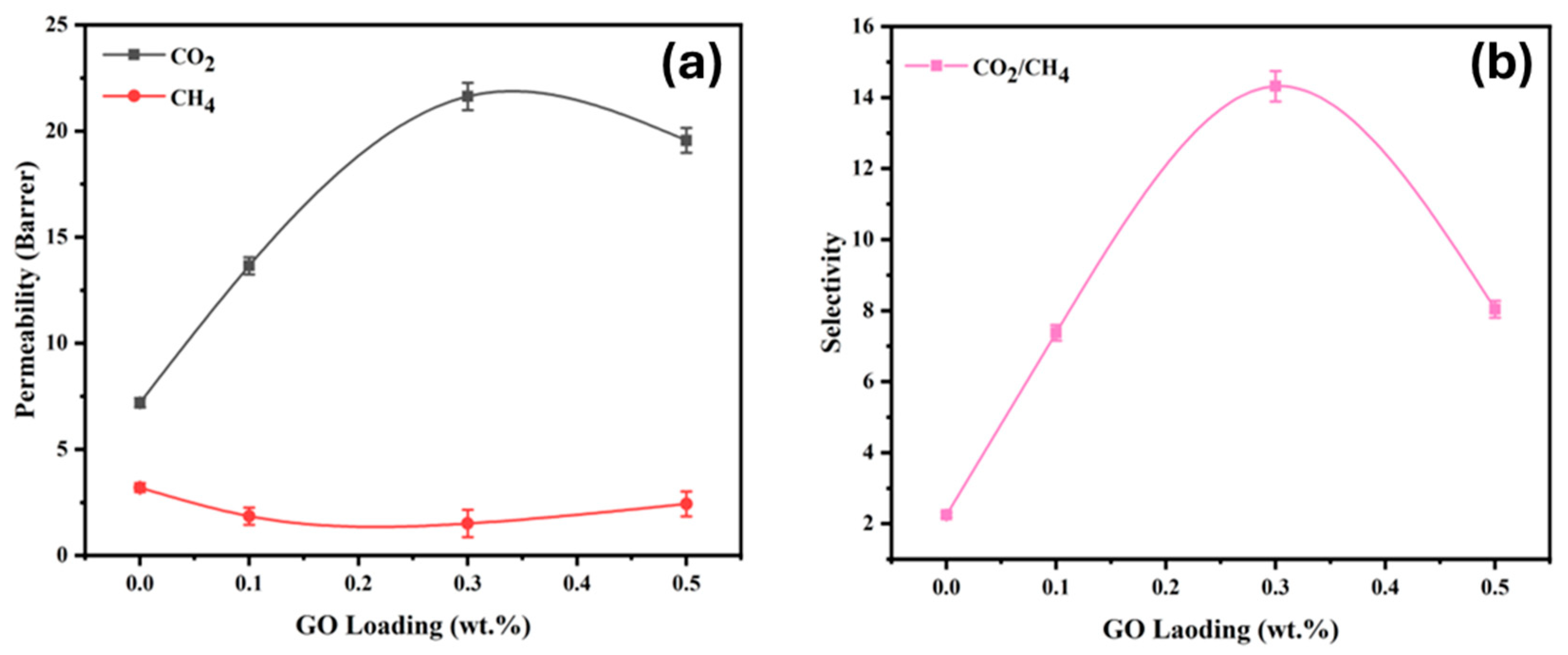

3.6. Gas Separation Performance

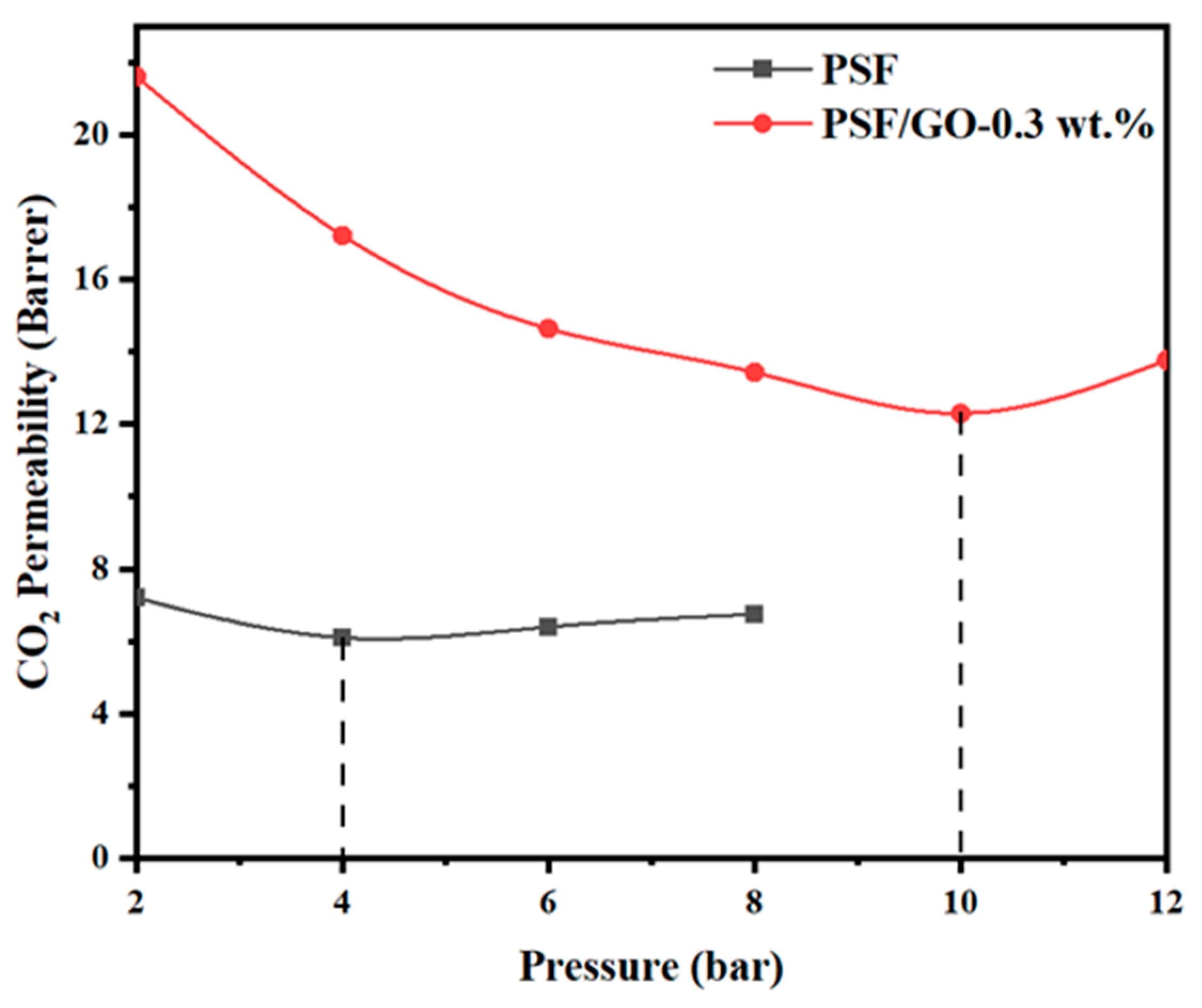

3.7. CO2-Induced Plasticization Effect

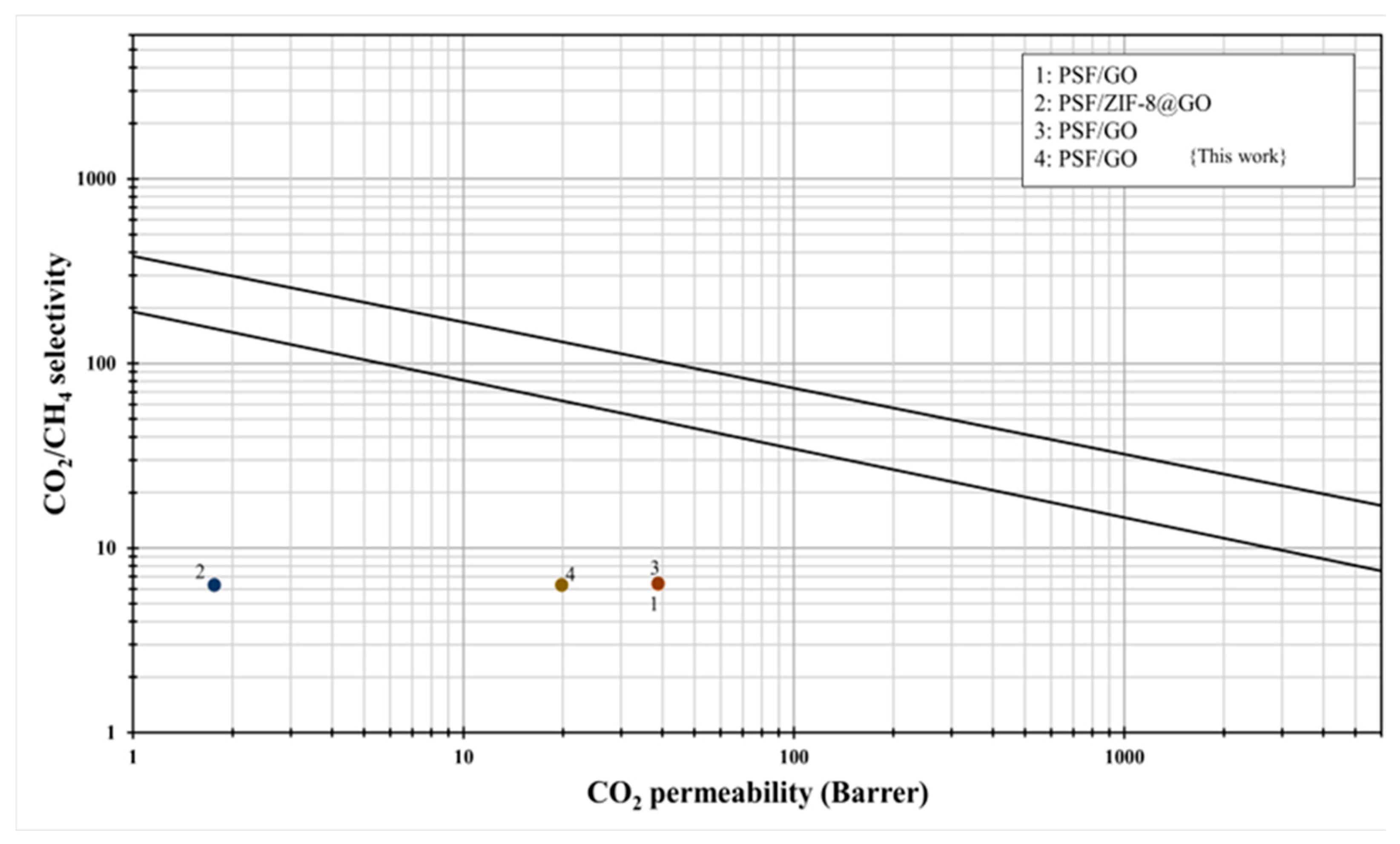

3.8. Comparison with Robson Upper Bound Relationship

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tabish, A.; Varghese, A.M.; Wahab, M.A.; Karanikolos, G.N. Perovskites in the Energy Grid and CO2 Conversion: Current Context and Future Directions. Catalysts 2020, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Karanikolos, G.N. CO2 capture adsorbents functionalized by amine–bearing polymers: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2020, 96, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Li, C.; Zhao, S.; Chai, M.; Hou, J.; Lin, R. Recent advances in the interfacial engineering of MOF-based mixed matrix membranes for gas separation. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 7716–7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M.; Lau, K.K.; Ahmad, F.; Mohd Laziz, A. A comprehensive review of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modelling of membrane gas separation process. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 105531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaraswamy Rangaraj, V.; Wahab, M.A.; Reddy, K.S.K.; Kakosimos, G.; Abdalla, O.; Favvas, E.P.; Reinalda, D.; Geuzebroek, F.; Abdala, A.; Karanikolos, G.N. Metal organic framework—Based mixed matrix membranes for carbon dioxide separation: Recent advances and future directions. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favvas, E.P.; Heliopoulos, N.S.; Karousos, D.S.; Devlin, E.; Papageorgiou, S.K.; Petridis, D.; Karanikolos, G.N. Mixed matrix polymeric and carbon hollow fiber membranes with magnetic iron-based nanoparticles and their application in gas mixture separation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 223, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazani, F.; Maleh, M.S.; Shariatifar, M.; Jalaly, M.; Sadrzadeh, M.; Rezakazemi, M. Engineered graphene-based mixed matrix membranes to boost CO2 separation performance: Latest developments and future prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadirkhan, F.; Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Wan Mustapa, W.N.F.; Halim, M.H.M.; Soh, W.K.; Yeo, S.Y. Recent advances of polymeric membranes in tackling plasticization and aging for practical industrial CO2/CH4 applications—A review. Membranes 2022, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahenthiran, A.V.; Jawad, Z.A.; Chin, B.L.F. Development of blend PEG-PES/NMP-DMF mixed matrix membrane for CO2/N2 separation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 124654–124676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sunarso, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, R. Current status and development of membranes for CO2/CH4 separation: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2013, 12, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ho, W.W. Polymeric membranes for CO2 separation and capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 628, 119244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.; Ismail, A.; Sanip, S.; Ng, B.; Aziz, M. Recent advances of inorganic fillers in mixed matrix membrane for gas separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 81, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.H.; Lau, H.S.; Yong, W.F. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)-based mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) for gas separation: A review on advanced materials in harsh environmental applications. Small 2022, 18, 2107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhattabi, L.; Harun, N.Y.; Zeeshan, M.H.; Waqas, S.; Hanbazazah, A. Gradient Cross-Linking Graphene Oxide–Integrated Nanofiltration Polyvinylpyrrolidone Membrane for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Removal. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 2025, 1822074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, S.; Bhoria, N.; Pokhrel, J.; Reddy, K.S.K.; Srinivasakannan, C.; Wang, K.; Karanikolos, G.N. Metal-organic framework/graphene oxide composite fillers in mixed-matrix membranes for CO2 separation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 212, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douna, I.; Farrukh, S.; Hussain, A.; Salahuddin, Z.; Noor, T.; Pervaiz, E.; Younas, M.; Fan, X.F. Experimental investigation of polysulfone modified cellulose acetate membrane for CO2/H2 gas separation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 39, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasi Kojabad, M.; Momeni, M.; Babaluo, A.A.; Vaezi, M.J. PEBA/PSf multilayer composite membranes for CO2 separation: Influence of dip coating parameters. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2020, 43, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulabbas, A.A.; Mohammed, T.J.; Al-Hattab, T.A. Parameters estimation of fabricated polysulfone membrane for CO2/CH4 separation. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, P.; Sasikumar, B.; Elakkiya, S.; Arthanareeswaran, G.; Ismail, A.; Youravong, W.; Yuliwati, E. Pillared cloisite 15A as an enhancement filler in polysulfone mixed matrix membranes for CO2/N2 and O2/N2 gas separation. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 86, 103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Varghese, A.M.; Reinalda, D.; Karanikolos, G.N. Graphene—Based membranes for carbon dioxide separation. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 49, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.M.; Shin, J.E.; Lee, H.D.; Park, H.B. Graphene and graphene oxide membranes for gas separation applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2017, 16, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, J.; Bhoria, N.; Wu, C.; Reddy, K.S.K.; Margetis, H.; Anastasiou, S.; George, G.; Mittal, V.; Romanos, G.; Karonis, D. Cu-and Zr-based metal organic frameworks and their composites with graphene oxide for capture of acid gases at ambient temperature. J. Solid State Chem. 2018, 266, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, P.; Wang, Z.; He, Y.; Qin, H.; Zeng, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J. MOFs meet membrane: Application in water treatment and separation. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 5140–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.C.; Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F. Highly permeable and selective graphene oxide-enabled thin film nanocomposite for carbon dioxide separation. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 64, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berean, K.J.; Ou, J.Z.; Nour, M.; Field, M.R.; Alsaif, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Ramanathan, R.; Bansal, V.; Kentish, S.; Doherty, C.M. Enhanced gas permeation through graphene nanocomposites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 13700–13712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Dai, Z.; Shao, L.; Eisen, M.S.; He, X. A review from material functionalization to process feasibility on advanced mixed matrix membranes for gas separations. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lively, R.P. Manufacturing nanoporous materials for energy-efficient separations: Application and challenges. In Sustainable Nanoscale Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 33–81. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeshan, M.H.; Ruman, U.E.; Shafiq, M.; Waqas, S.; Sabir, A. Intercalation of GO-Ag nanoparticles in cellulose acetate nanofiltration mixed matrix membrane for efficient removal of chromium and cobalt ions from wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeshan, M.H.; Yeong, Y.F.; Chew, T.L. A comprehensive study on the effect of air gap distances on morphology and gas separation performance of cellulose triacetate/polysulfone dual-layer hollow fiber membrane. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2025, 100, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, K.A.; Mansoor, B.; Mansour, A.; Khraisheh, M. Functional graphene nanosheets: The next generation membranes for water desalination. Desalination 2015, 356, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahri, K.; Wong, K.C.; Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F. Graphene oxide/polysulfone hollow fiber mixed matrix membranes for gas separation. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 89130–89139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Chen, B. Reinforcement and interphase of polymer/graphene oxide nanocomposites. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 3637–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainath, K.; Modi, A.; Bellare, J. CO2/CH4 mixed gas separation using graphene oxide nanosheets embedded hollow fiber membranes: Evaluating effect of filler concentration on performance. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2021, 5, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroon, M.; Ismail, A.; Matsuura, T.; Montazer-Rahmati, M. Performance studies of mixed matrix membranes for gas separation: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 75, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Zhao, J.; Guan, K.; Shen, J.; Jin, W. Highly efficient recovery of propane by mixed-matrix membrane via embedding functionalized graphene oxide nanosheets into polydimethylsiloxane. AlChE J. 2017, 63, 3501–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-C.; Chang, C.-S.; Ruaan, R.-C.; Lai, J.-Y. Effect of free volume and sorption on membrane gas transport. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 226, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Silva, R.; Endo, M.; Terrones, M. Graphene oxide films, fibers, and membranes. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016, 5, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, I.S.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, J.; Kang, Y.S.; Kang, S.W. The platform effect of graphene oxide on CO2 transport on copper nanocomposites in ionic liquids. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 251, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W. Membrane technology and applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Varghese, A.M.; Reddy, K.S.K.; Romanos, G.E.; Karanikolos, G.N. Polysulfone mixed-matrix membranes comprising poly (ethylene glycol)-grafted carbon nanotubes: Mechanical properties and CO2 separation performance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 11289–11308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaady, M.; Waqas, S.; Zeeshan, M.H.; Almarshoud, M.A.; Maqsood, K.; Abdulrahman, A.; Yan, Y. Efficient CO2/CH4 Separation Using Polysulfone/NH2-MIL-125(Ti) Mixed Matrix Membranes. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 11972–11979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miricioiu, M.G.; Iacob, C.; Nechifor, G.; Niculescu, V.-C. High selective mixed membranes based on mesoporous MCM-41 and MCM-41-NH2 particles in a polysulfone matrix. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsaady, M.; Waqas, S.; Almarshoud, M.A.; Maqsood, K.; Abdulrahman, A.; Yan, Y. Polysulfone/Graphene Oxide Mixed Matrix Membranes for Improved CO2/CH4 Separation. Membranes 2025, 15, 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120386

Alsaady M, Waqas S, Almarshoud MA, Maqsood K, Abdulrahman A, Yan Y. Polysulfone/Graphene Oxide Mixed Matrix Membranes for Improved CO2/CH4 Separation. Membranes. 2025; 15(12):386. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120386

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsaady, Mustafa, Sharjeel Waqas, Mohammed A. Almarshoud, Khuram Maqsood, Aymn Abdulrahman, and Yuying Yan. 2025. "Polysulfone/Graphene Oxide Mixed Matrix Membranes for Improved CO2/CH4 Separation" Membranes 15, no. 12: 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120386

APA StyleAlsaady, M., Waqas, S., Almarshoud, M. A., Maqsood, K., Abdulrahman, A., & Yan, Y. (2025). Polysulfone/Graphene Oxide Mixed Matrix Membranes for Improved CO2/CH4 Separation. Membranes, 15(12), 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120386