1. Introduction

Almost all industrial processes rely on organic solvents, with abundant use in a broad range of industries, from pharma and fine chemicals, over food, nutraceuticals, and cosmetics, to biofuels and paints [

1]. In all these industries, solvents serve a variety of functions in the manufacture of essential chemicals and materials in our daily lives. However, the life cycles of industrial solvents, comprising production, transportation, use, and finally disposal, introduce sources of emissions that potentially impact human health and the environment in which they are released. Conventional solvent waste handling methods, especially incineration, are accompanied by significant increases in the overall energy, ecological, and safety footprint of solvent-intensive industries [

2]. The continuously growing demand for solvents worldwide necessarily leads to higher levels of waste generation and higher waste disposal costs as well. Therefore, process intensification strategies are being considered to mitigate the growing costs as well as environmental, health, and safety concerns connected with waste solvent handling, prompted also by evolving regulatory frameworks promoting environmentally sound waste management methods.

Especially, solvent recovery is a major objective in the industries mentioned above to reduce production costs and improve the sustainability and circularity of current manufacturing practices. Thermal energy-based separation processes, such as distillation, are widely applied due to their exceptional performance in delivering high-purity streams [

3]. However, these energy-intensive processes result in high operating costs and carbon emissions. The energy required for thermal separations is usually derived from steam produced by burning fossil fuels. In the case of solvents that form an azeotrope with another compound or have close boiling points, the energy consumption is even higher. Moreover, global energy costs are expected to increase significantly owing to the decline in the use of fossil fuels and the 2050 climate goals [

4]. Using membranes either standalone or as hybrid systems has the potential to reduce energy consumption and CO

2 emissions of thermal solvent recovery and dehydration processes significantly. Highly selective and energy-efficient pervaporation-based processes can reduce capital costs and energy consumption of traditional distillation processes by up to 40% while having substantial reductions in CO

2 emissions [

5].

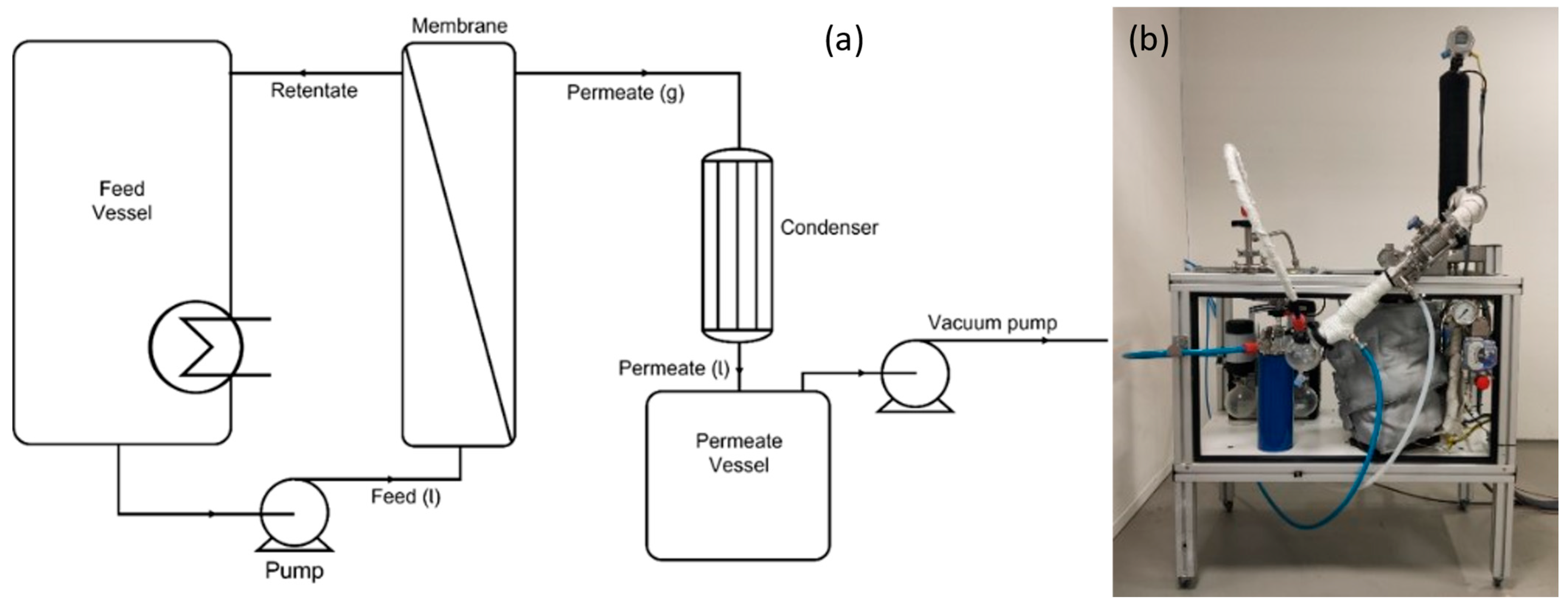

In pervaporation, liquid mixtures are separated at the molecular level by the vaporization of target compounds through a selective membrane. The process has been coined “pervaporation” because of the unique co-occurring phenomena of “permeation” and “evaporation”, i.e., permselective transport and vaporization of molecules diffusing through the membrane [

6]. The driving force for transport is a gradient in partial vapor pressure of the permeants between the liquid feed and vaporous permeate sides of the membrane. In practice, a vacuum is usually maintained at the permeate side. Since different compounds permeate at different rates, a substance at low concentration in the feed stream can be significantly enriched in the permeate. Pervaporation is generally employed when the target compounds are small, (semi-) volatile, and present at relatively low concentrations.

Despite some obvious similarities, some features make pervaporation significantly more efficient than distillation. Most notably, pervaporation is not governed by vapor-liquid equilibria but solely by the water/solvent separation factor of the membrane [

7]. Whereas distillation is entirely determined by the thermodynamic equilibrium between the vapor and liquid phases, pervaporation predominantly relies on the affinity of the target molecules for the membrane [

6]. This means that the permeate composition is not defined by the vapor-liquid equilibrium (VLE) but by the permeability of the compounds, which depends on their solubility and diffusion rate in the membrane. Hence, by using highly selective membranes, mixtures can be separated irrespective of the boiling points of the liquids and the occurrence of azeotropes. Since solute transport is dependent on the solubility of the penetrants in the membrane, the latter is chosen such that it interacts intensely with the target compounds. In the case of dehydration of organic solvents, hydrophilic membranes based on polymers, ceramics, or zeolites are being used [

8,

9]. Moreover, contrary to distillation involving repeated vaporization and condensation of the entire mixture, pervaporation only requires vaporization of the permeating fraction.

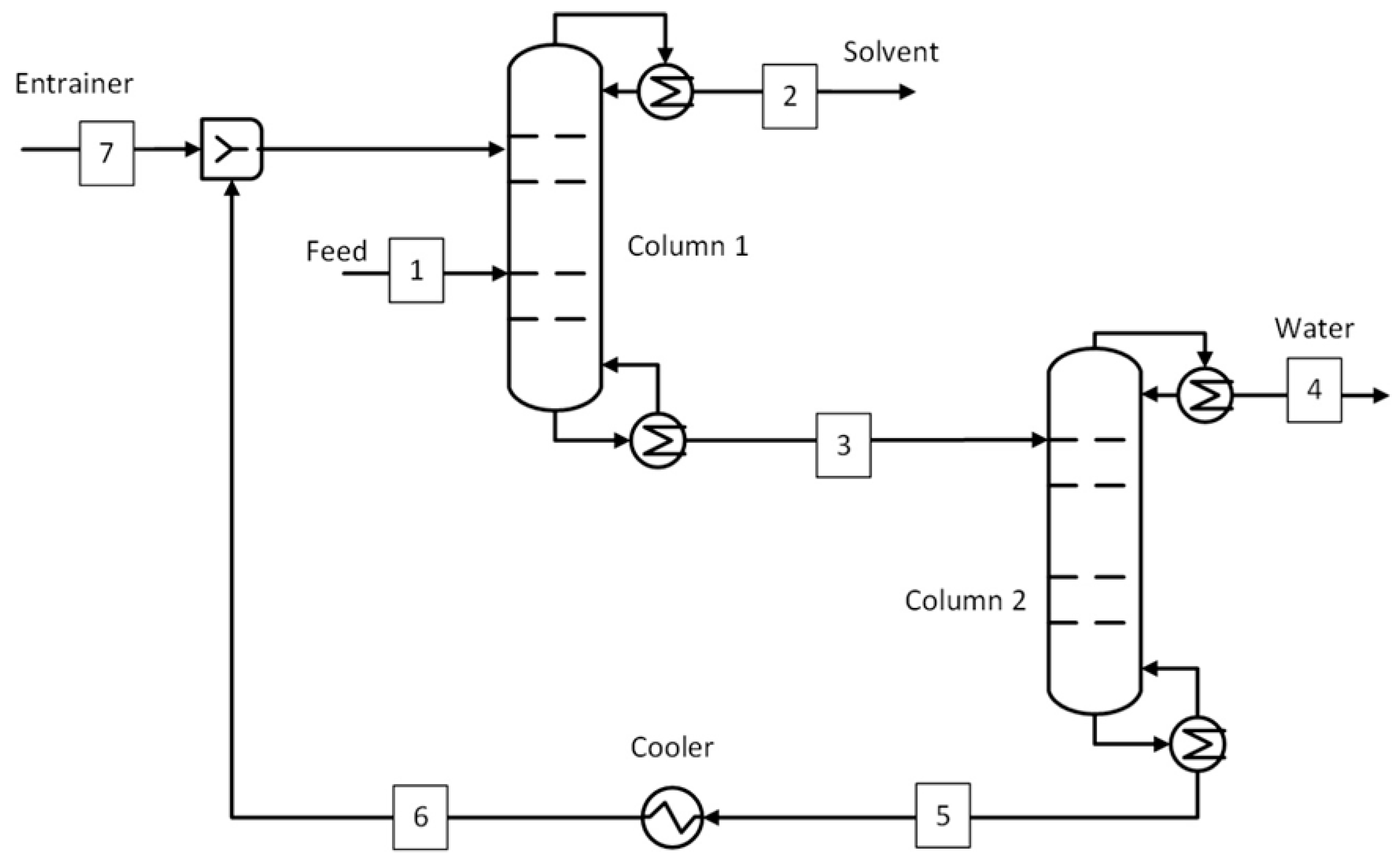

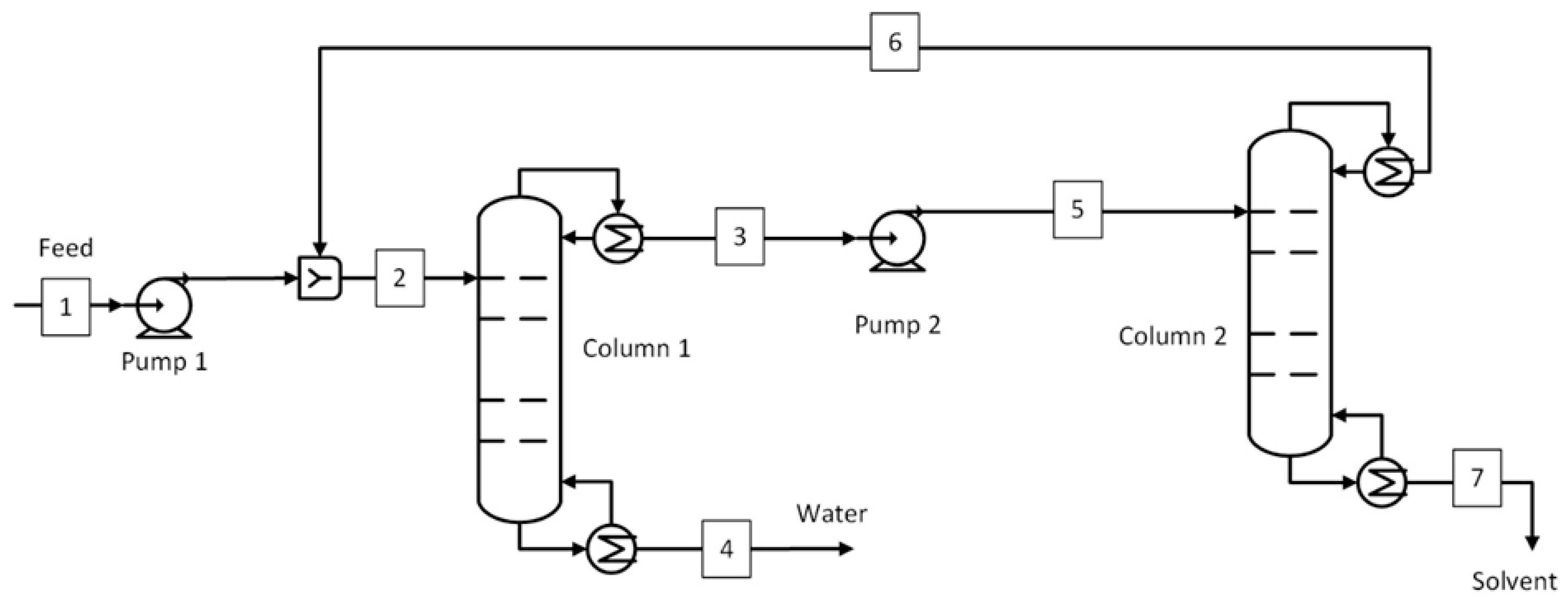

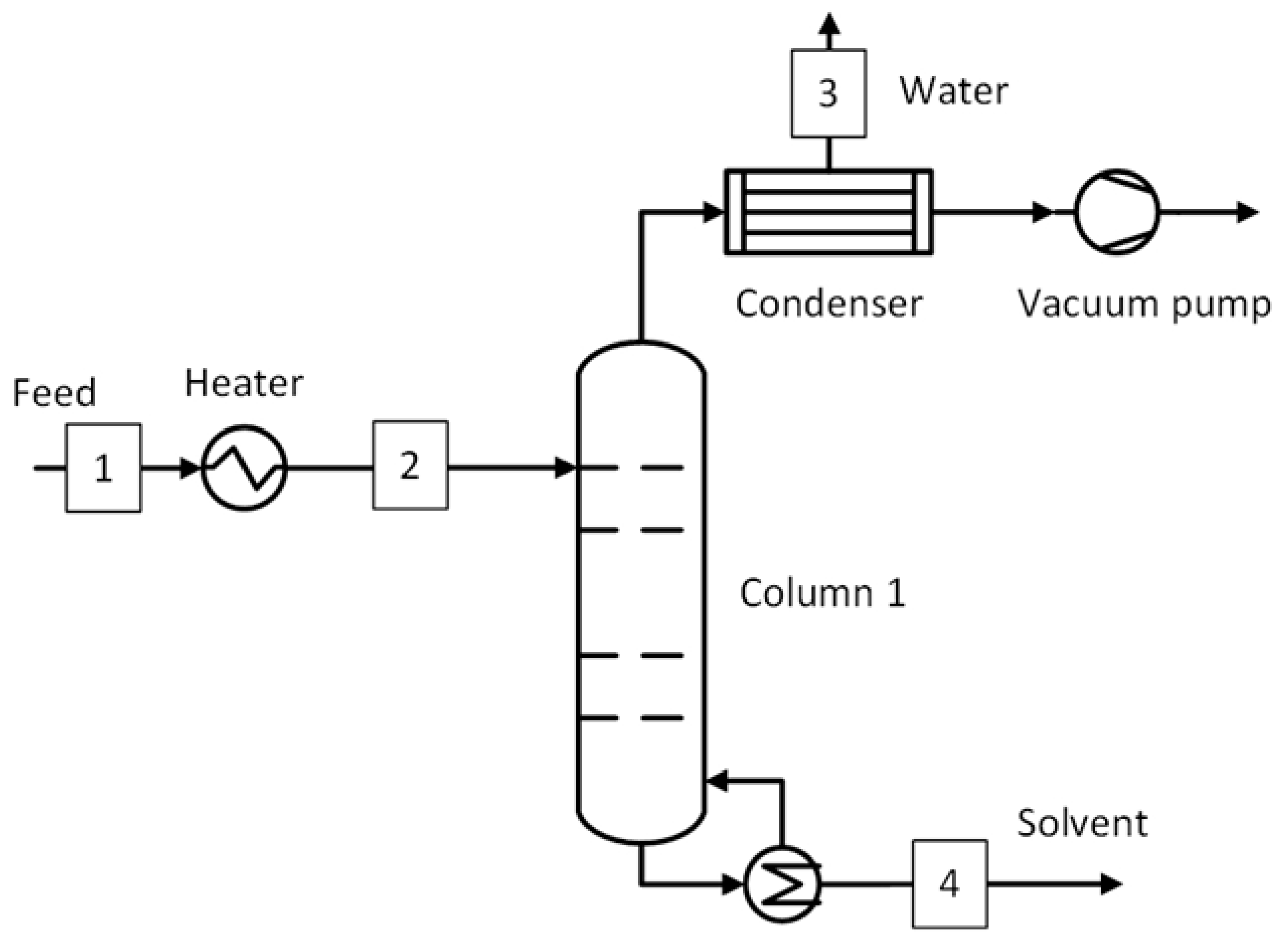

Pervaporation can be used as a standalone process, but owing to their modularity, membrane units can also be easily retrofitted to existing distillation plants. Such hybrid separations, where distillation and pervaporation are synergistically used, offer wide opportunities for debottlenecking and intensification of thermal separation processes [

7]. This way, pervaporation may allow for significant reductions in energy requirements, often coupled with flexible increases in capacity and productivity, as well as improvements in raw material usage and reductions in waste volumes [

7]. Hybrid distillation-pervaporation processes are being implemented in the industry mainly for dehydration and separation of solvents close to and beyond the azeotropic point, often as a cost-effective alternative for azeotropic or extractive distillation. Whereas distillation of mixtures with an azeotropic composition or with components with low relative volatility or close boiling points is energetically expensive, and auxiliary substances are usually required, pervaporation is performed in the absence of any additives, hence avoiding the need for extra recovery columns while eliminating the risk of product contamination.

The pervaporation membrane market is set to grow significantly, driven by the demand for solvent recovery and the industry’s need to reduce carbon footprints and reuse raw materials. Valued at 4.8 billion euros in 2023, the market is expected to grow at a CAGR of 6.9% until 2031 [

10]. The HybSi

® AR membrane developed and commercialized by Pervatech is based on hybrid silica [

5]. It is a robust, acid-resistant ceramic pervaporation membrane, which separates water and small polar compounds from various organic solvents and process mixtures [

11]. It is used in industries such as chemical, pharmaceutical, food, and biotech for the dehydrating process and waste streams. HybSi

® AR offers superior chemical stability, higher operating temperatures, and a greater water/solvent separation factor, leading to significant operational flexibility and enhanced energy savings in dehydrating aggressive solvent streams [

5,

12]. Pervatech has already implemented a full-scale isopropanol (IPA) dehydration plant using these HybSi

® AR membranes [

5]. More information on the advantages of these hybrid silica membranes can be found elsewhere [

13,

14].

In this study, we present a comprehensive techno-economic and environmental assessment of pervaporation-based solvent dehydration processes using HybSi

® AR membranes, applied across five industrially relevant solvent–water systems: isopropanol (IPA), acetonitrile (ACN), tetrahydrofuran (THF), acetic acid (ACA), and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). A variety of advanced distillation processes are commonly used for the dehydration of these solvents, including azeotropic, extractive, pressure-swing, and vacuum distillation. Many papers focus on the dehydration of IPA [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], ACN [

22,

23,

24,

25], THF [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], ACA [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38], and NMP [

39,

40,

41,

42] by pervaporation, predominantly using novel laboratory-made membranes; however, a comprehensive techno-economic and environmental evaluation and benchmarking against distillation has never been reported. Distinct from previous works that often focus on individual solvents or simulated systems, this study integrates experimentally validated membrane performance data with Aspen Plus simulations to evaluate multiple hybrid process configurations, including D-PV, D-PV-D, and standalone PV, in comparison with traditional distillation-based benchmarks. Although the HybSi

® AR membrane itself is commercially available, its innovative use in high-temperature hybrid configurations for solvent dehydration, combined with experimentally validated performance data and process-level sustainability assessment, represents a significant contribution. In this context, the term ‘innovative’ in the title refers to the novel application and integration of the membrane, rather than the development of a new material. A novel contribution of this work is the introduction of a unified decision-making index, COPCO (COst savings per unit tonne of CO

2 reduction), which enables simultaneous interpretation of both economic and environmental performance. By mapping each configuration within a cost-emission tradeoff space, we provide actionable guidance for solvent-specific process selection. This approach not only strengthens the case for pervaporation as a process intensification strategy but also offers a generalizable framework to support sustainable process design in solvent recovery. The insights obtained from this study are expected to further push the market uptake of pervaporation technology, particularly using HybSi

® AR membranes, and provide cost-efficient solutions to various pertinent dehydration challenges across solvent-intensive industries.

3. Results and Discussion

The results from the pervaporation experiments using HybSi

® AR membranes and the economic and environmental assessments are presented in this section. The experimental results, including the average permeate flux and permeate quality and their implications on the membrane area, are discussed. The technical performance of the pervaporation-based processes in terms of utility consumption, recovery efficiency, and energy intensity is discussed in comparison with the benchmark processes. Subsequently, the results of the economic and environmental performance in terms of the

LCOS, emission intensity, and

COPCO index are also discussed. Lastly, important results from the sensitivity analysis are also discussed here for some solvent systems, and the remaining results are given in the

Supplementary Material. The results for IPA presented in this study are reproduced from our earlier publication for consistency and comparative analysis [

50].

3.1. Experimental Pervaporation Results

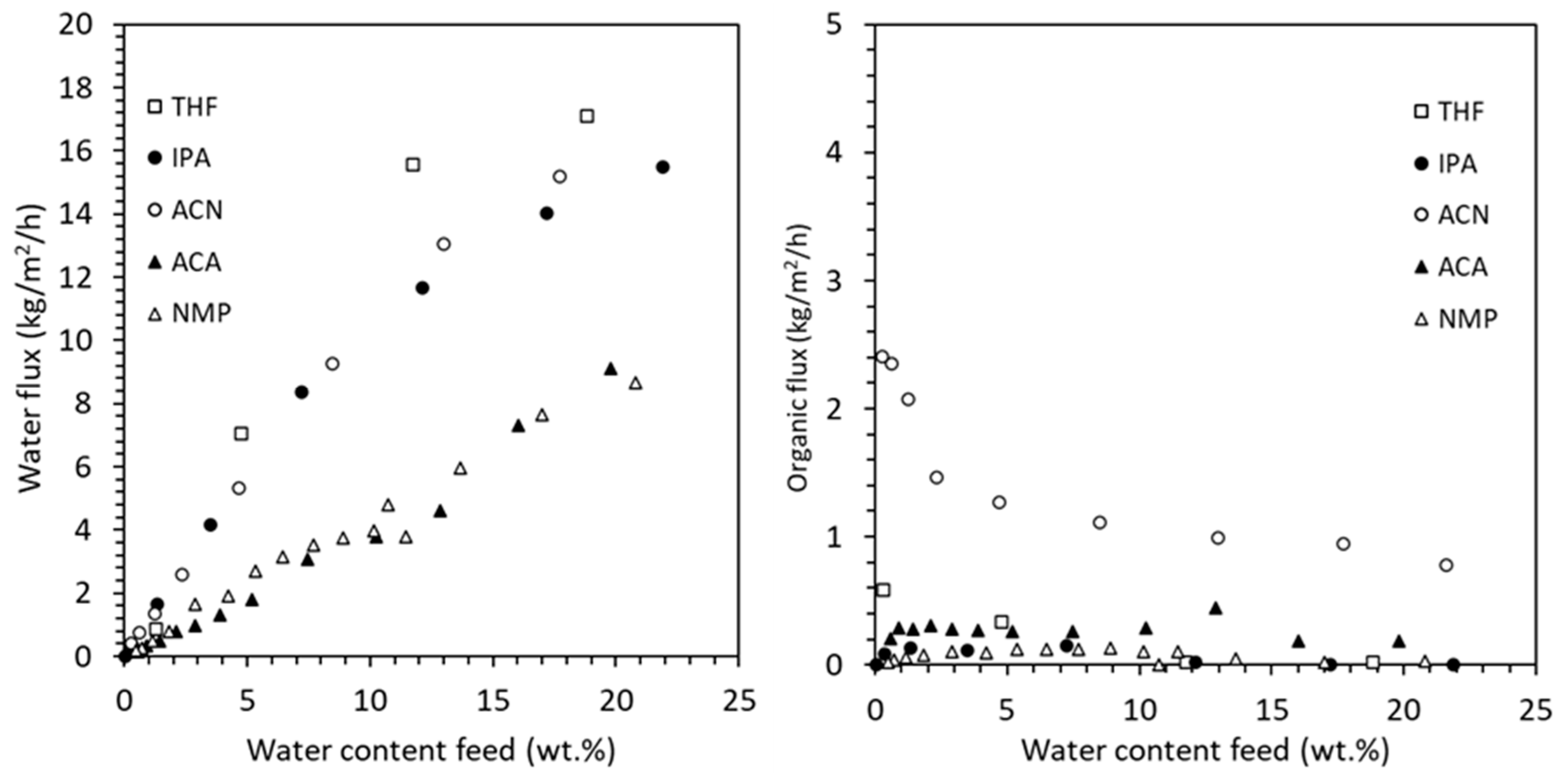

Figure 9 presents the measured water flux (left) and organic flux (right) as a function of water content in the feed for all five solvent–water systems tested using HybSi

® AR membranes. As expected, water flux increases with feed water content due to the enhanced driving force, with THF and ACN exhibiting the highest water fluxes. In contrast, organic solvent fluxes remain low across all systems, confirming a high water/solvent separation factor. Slightly elevated organic flux was observed for ACN, likely due to its low viscosity and small molecular size.

While vapor pressure and molecular size are important determinants of pervaporation flux, the observed differences between solvents also reflect the influence of solvent-specific properties. In HybSi® AR membranes, separation primarily follows a molecular sieving mechanism. However, the effective flux is also impacted by factors such as membrane–solvent interactions, solvent viscosity, and polarity. For instance, acetonitrile (ACN) exhibited higher flux than NMP, which can be attributed not only to its smaller molecular size but also to its lower viscosity and weaker interaction with the membrane material. In contrast, NMP’s higher viscosity and stronger hydrogen bonding likely reduced transport rates, even under similar operating conditions. This indicates that a combination of steric, thermodynamic, and transport-related effects governs permeation performance.

The corresponding separation factors (α), summarized in

Table 6, ranged from 85 (ACN) to 977 (IPA), further confirming the membrane’s strong preference for water transport. It is also important to note that, at the start of some experiments, the system was unable to maintain isothermal operation at 130 °C due to high initial flux. In these cases, the measured fluxes at slightly lower temperatures were extrapolated to 130 °C using vapor–liquid equilibrium (VLE) data to correct for differences in driving force. This ensures consistency in the performance comparison and provides input for accurate process simulation.

The average water and solvent fluxes, along with the permeate quality (or selectivity) obtained from experiments, are presented in

Table 7. For the hybrid processes (D-PV and D-PV-D), the inlet water concentration differs for every solvent. This concentration was fed to the pervaporation module and was obtained after the first distillation column. For the solvents IPA, ACN, and THF, the inlet water concentration was kept near their azeotropic compositions. For the solvents ACA and NMP, which do not form azeotropes, the inlet water concentration was adjusted to ensure that most of the solvent was recovered from the bottom at target purity while maintaining the mass balance in the column. For the standalone PV process, the inlet water concentration was the same as the initial feed (50 wt.%). The outlet water concentration was kept the same for each process in the solvent systems. The processes D-PV and PV had 0.5 wt.% as the outlet water concentration, which is equal to the target purity. In the D-PV-D process, an outlet water concentration of 5 wt.% was selected for all solvents to break the azeotrope, except for THF, which required a concentration of 2 wt.% due to its lower azeotropic composition.

The general trend is that by increasing the inlet water concentration while keeping the outlet water concentration constant, the average water flux also increases. The driving force in pervaporation is a chemical potential gradient, which is largely determined by the concentration of the permeating component (water in this case) in the feed. As the water concentration decreases in the feed, the chemical potential difference between the feed and permeate side diminishes, leading to lower water flux through the membrane. Similarly, when the inlet water concentration was kept constant and the outlet water concentration was increased, the average water flux obtained was higher. This is due to avoiding lower flux values at lower concentrations (such as at 0.5 wt.%) while time-averaging the experimental data. The standalone PV process can be used to compare the average water flux for all solvents since the inlet and outlet water concentrations are the same. The average water flux is in the following order from highest to lowest values: ACN > IPA > THF > ACA > NMP. The required membrane area is not solely determined by the average water flux, but it also depends on the water content and flow rate of the feed stream. The solvent flux remains relatively low across all cases, indicating a high water/solvent separation factor and effective separation. The ACN solvent has the highest flux, while the NMP solvent has the lowest flux, which is also reflected in the permeate quality. Among other reasons, ACN is a small molecule and has a higher vapor pressure than NMP, which drives a greater flux through the membrane during the pervaporation process.

3.2. Technical Performance

The technical performance in terms of required membrane area, recovery efficiency, energy and utility consumption, and energy intensity for all solvent systems is shown in

Table 8. The membrane area was calculated based on the average flux and permeate flow rates obtained from the experiments. The standard module generally has 3 m

2 of membrane area, but a design of 10 m

2 is also available in the market, and smaller modules, depending upon the requirement, can also be designed. The recovery efficiency allows for quantification of the solvent loss in the permeate stream and assists in comparison between the benchmark and pervaporation-based processes. The cooling water shown here represents the cooling duty required for a particular process and thus is not consumed. It is assumed that it is recycled entirely except for some evaporative losses. This metric is particularly important in selecting the separation process suitable for water-scarce locations. The energy consumption in terms of electricity and steam allows for comparison and identification of the primary energy source of all the processes. This will help in choosing the process that primarily relies on the preferred energy type (electricity or heat). It will also help in accurately sizing the equipment associated with energy supply, such as an on-site boiler for steam generation. If the energy type is not the main concern, then the energy intensity, which includes both electricity and heat, could be used for overall comparison.

For IPA dehydration, the recovery efficiencies remain almost the same for all four cases investigated, with the highest recovery efficiency of 99.8% obtained by the D-PV-D case. Further, the D-PV-D case also requires the smallest membrane area due to the use of pervaporation to only break the azeotrope. The largest membrane area was required in standalone PV, where all the feed water is removed on the permeate side, resulting in the largest electricity consumption (by vacuum pump) compared to other cases. When it comes to steam requirements, the benchmark azeotropic distillation emerged as the most energy-consuming option, which is also reflected in its energy intensity (2.0 MWh/t-IPA). The lowest steam was required in the D-PV process, resulting in an energy intensity of only 0.9 MWh/t-IPA, emerging as the most energy-efficient option. The AD case has the largest cooling water requirement, mainly in the condensers of the three distillation columns. The cooling water requirement follows the number of distillation columns involved. The higher the number of distillation columns, the higher the cooling water requirement. While AD and D-PV-D offered higher recovery efficiencies, their higher utility consumption made them less favorable. The standalone PV with no distillation columns requires the largest membrane area and has the lowest cooling water requirement and relatively lower energy intensity, presenting a balanced approach.

The recovery efficiencies are variable among the four cases investigated for ACN dehydration. This variation stems from the fact that the solvent loss observed in the permeate during the experiments was significantly higher, as shown in

Table 7. Though the benchmark ED case has the highest recovery efficiency (99.5%), its high energy intensity, steam, and cooling water consumption make it highly unattractive. The hybrid D-PV option has the lowest energy intensity (1.0 MWh/t-ACN) but suffers from relatively lower recovery efficiency and considerable cooling water consumption. The hybrid D-PV-D option with the lowest membrane area requirement offers moderate recovery efficiency and energy intensity. However, the cooling water requirement was significantly larger, making it unattractive for water-scarce locations. The standalone PV case has the lowest cooling water requirement, making it suitable for water-scarce locations. Further, with lower energy intensity (1.1 MWh/t-ACN), this can be an attractive option if the solvent losses can be ignored.

For THF dehydration, not much variation was observed in the recovery efficiencies, with the highest being 99.8%, achieved by the hybrid D-PV-D case. The membrane area requirement observed was also higher than that required in the IPA and ACN solvent systems due to relatively lower permeate fluxes. The benchmark PSD and the standalone PV have similar energy intensities (1.1 vs. 1.0 MWh/t-THF), but the significant difference in the cooling water consumption makes the standalone PV a highly attractive option between the two. The hybrid D-PV and D-PV-D cases also show similar energy intensities (0.6 vs. 0.7 MWh/t-THF), but with lower cooling water requirements, the D-PV case emerged as the best option for THF dehydration.

Since ACA does not form an azeotrope and has a higher boiling point than water, it was recovered from two separate streams (column bottom and retentate streams). Consequently, a high inlet water concentration to the pervaporation module was observed, resulting in a higher membrane area requirement. The benchmark ED process achieved a complete solvent recovery and had moderate energy intensity (1.5 MWh/t-ACA) but suffered from significant cooling water consumption, making it unsuitable for water-scarce locations. The hybrid D-PV and D-PV-D processes have moderate recovery efficiencies, the highest energy intensities, and cooling water consumption, making them highly unattractive. The high steam requirement is due to the thermal energy required in the first distillation column, feed, and interstage heating of almost all the water. The standalone PV option with the lowest energy intensity (1.0 MWh/t-ACA) and cooling water consumption (483 m3/yr) emerged as the most suitable option for ACA dehydration but suffers from a lower recovery efficiency (96.6%) and needs a significantly larger membrane area (58 m2).

Like ACA, NMP also does not form an azeotrope with water, and it is recovered from two separate streams (column bottom and retentate streams). The benchmark VP process seems to be the best option with the lowest energy intensity (0.8 MWh/t-NMP), moderate recovery efficiency (99.5%), and cooling water requirement. The standalone PV emerged as the second-best option with an energy intensity of 1.0 MWh/t-NMP and a recovery efficiency of 98.9%. It also has the lowest cooling water requirement but needs a very large membrane area (68 m

2) due to very low permeate flux (see

Table 7), which may have a large influence on the costs. Despite achieving 100% recovery efficiencies, the hybrid D-PV and D-PV-D processes proved to be highly unattractive due to larger energy intensities and cooling water requirements.

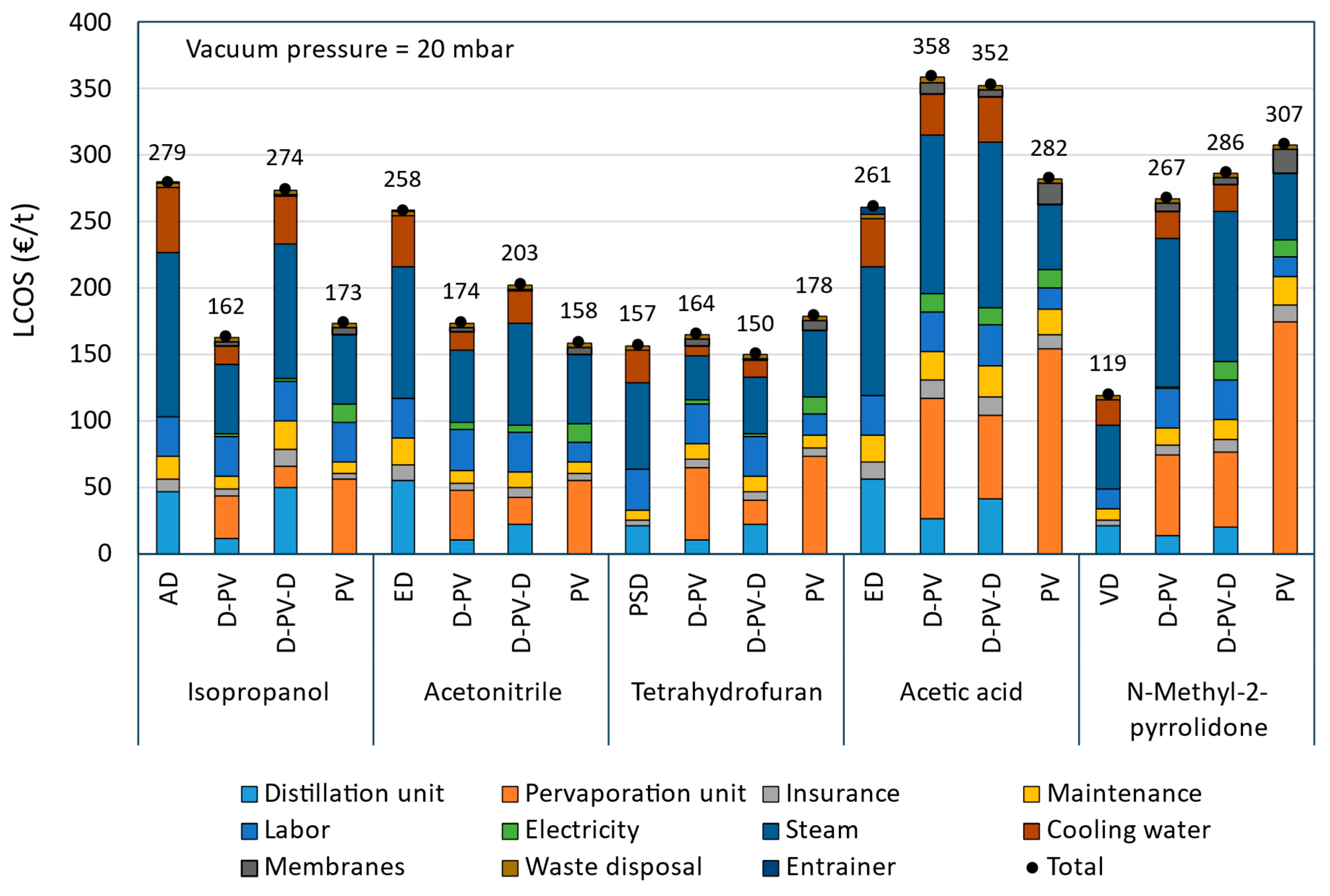

3.3. Economic Performance

The annualized capital and operating costs for all the cases investigated for five solvent systems are given in

Table 9. The reduction in the LCOS with respect to their respective benchmark process is also given in the table, while the LCOS breakdown is presented in

Figure 10. In the figure, the capital cost is divided into the distillation and the pervaporation units and is based on the economic data shown in

Tables S21–S40. Specifically, the capital cost of the columns used is based on the design data shown in

Tables S41–S45 of the

Supplementary Information. The capital cost breakdown, including the contribution from all the equipment, is shown in

Figures S2–S6, where the

IS heater refers to the interstage heater and

pervap consists of only the initial membrane costs, while the replacements are included in the operating costs.

The AD process serves as the benchmark for comparison among IPA dehydration processes. It has a high operating cost due to significantly high steam and cooling water consumption, as shown in

Figure 10, resulting in the highest LCOS. The D-PV process shows some reduction in capital cost but a significant reduction in operating cost compared to AD, leading to a 42% reduction in the LCOS. This makes it a cost-effective alternative. The D-PV-D process has the highest capital cost due to the involvement of two distillation columns and consequently shows a high operating cost due to higher steam and cooling water demand, resulting in an LCOS close to that of AD, with only a 2% reduction. This indicates that the additional distillation step may not be cost-effective. The PV process has a moderate capital cost and the lowest operating cost among the processes compared, resulting in a 38% reduction in the LCOS. This makes it a competitive option in terms of cost-efficiency.

For ACN dehydration, the benchmark ED process has the highest capital and operating costs due to the involvement of two distillation columns that require a large amount of steam and cooling water, consequently leading to a very high LCOS. The D-PV process shows a considerable reduction in capital cost compared to ED due to the replacement of the second distillation column with the pervaporation module. It also shows a significant reduction in operating costs due to a reduction in utilities consumption, resulting in a 33% reduction in the LCOS. The hybrid D-PV-D process, though involving two distillation columns, has the lowest capital cost due to smaller-sized columns and a pervaporation module. However, it still requires a moderate operating cost, which leads to a 21% reduction in LCOS compared to ED. The standalone PV process shows a moderate capital cost and the lowest operating cost among the compared processes, resulting in a 39% reduction in the LCOS. This makes it the most cost-effective option for ACN dehydration.

The benchmark PSD process for THF dehydration has the lowest capital cost due to smaller-sized columns but has the highest operating cost due to high utility consumption among the four cases investigated. The operating costs are also lower than those observed in benchmarks AD and ED of IPA and ACN solvent systems, respectively. This is due to the absence of an entrainer that is necessary in AD and ED processes, which requires additional steam and cooling water in the columns. The D-PV process shows a significant reduction in the operating cost compared to PSD. However, it has the highest capital cost mainly due to the contribution from the pervaporation module. This results in a slightly higher LCOS (€164/t-THF), representing a 5% increase compared to PSD. This increase can be easily overcome at a lower membrane price or higher permeate flux, which will be discussed in

Section 3.4 on sensitivity analysis. The hybrid D-PV-D process with moderate capital and operating costs emerged as the most cost-effective option with a 4% reduction in the LCOS compared to PSD. The potential for further reducing the LCOS by using cheaper membranes or increasing permeate flux is limited, as these factors contribute only modestly to the overall LCOS. The standalone PV process is the least cost-effective option as it shows the highest capital and moderate operating costs, leading to a 14% increase in the LCOS compared to PSD. Since the capital cost is mainly due to the pervaporation module, using cheaper membranes or increasing permeate flux has the potential to reduce the LCOS.

For ACA dehydration, the benchmark ED process showed the lowest capital and moderate operating costs, leading to an LCOS of €261/t-ACA. The hybrid processes D-PV and D-PV-D showed significantly higher capital and operating costs, resulting in a significant increase in LCOS (36% and 38%) compared to the ED process.

Figure 10 shows that the pervaporation module’s capital cost and the utility consumption (steam and cooling water) of the operating costs are the main contributing factors. The standalone PV process has the highest capital cost among the four cases investigated, and this is only due to the expensive pervaporation module. However, the significant reduction in the operating cost leads to the LCOS of €282/t-ACA, which is only a 9% increase compared to the benchmark ED process. Further reduction in capital cost is only possible if the membrane price drops or with enhanced permeate flux, which can be realized by increasing feed temperature. Waste heat could be utilized for this; otherwise, this will influence energy consumption and overall costs.

For NMP dehydration, the VD process serves as the baseline with the lowest costs. Though NMP has a high boiling point, the use of a vacuum reduces the energy requirement in the distillation column. The pervaporation-based processes (D-PV, D-PV-D, and PV), despite their potential benefits, result in significantly higher LCOS due to their high capital and operating costs, with standalone PV as the least interesting option. The pervaporation module to the capital cost and the steam consumption to the operating cost are the main contributing factors. It is clear from

Figure 10 that the likelihood of a reduction in LCOS below the benchmark VD process appears to be low. More discussion on this is presented in

Section 3.4 on sensitivity analysis.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

This section discusses the sensitivity of the LCOS to various technical and economic parameters. The parameters selected for sensitivity analysis include feed flow rate, permeate flux, membrane module price, membrane lifetime, steam price, and cooling water price. The results are presented in

Figures S7–S11 of the

Supplementary Information, with only the most significant findings discussed here. Firstly, the general effect of these parameters is discussed, followed by key observations from the results of each solvent system. The feed flow rate varied from 100 to 3500 kg/h, with 1000 kg/h as the base value for all solvent-water mixtures. Typically, as the feed flow rate increases, LCOS might decrease due to economies of scale, but this can vary depending on system specifics. This is due to equipment such as distillation columns, vacuum pumps, chillers, etc., that scale non-linearly with their capacity. The pervaporation module was assumed to be modular and therefore scales linearly, not contributing to the economies of scale effect. Beyond a particular feed flow rate, the effect of economies of scale diminishes and eventually becomes negligible. However, at lower feed flow rates, the impact of economies of scale becomes more significant, potentially making the benchmark process more attractive in terms of LCOS. However, at these flow rates, operating a distillation column can present challenges, such as heat losses due to a high surface area-to-volume ratio, as well as control and stability issues. Therefore, pervaporation-based systems may be the best options at low flow rates.

The permeate flux varied from 2 to 30 kg/h/m2, with different base values for pervaporation-based processes of different solvent systems. The flux is directly proportional to membrane area, which is reflected in capital and operating costs. Higher permeate flux usually leads to lower LCOS as more product is obtained per unit of membrane area. However, beyond a certain flux value, the cost savings from reducing the membrane area are minimal due to its smaller contribution to LCOS.

The membrane module price (including membranes, housing, and seals/gaskets) varied from 20% to 160%, with 100% as the base value. An increase in membrane price generally raises the LCOS, reflecting higher capital costs, especially in processes that require a larger membrane area. Similarly, longer membrane life typically reduces the LCOS, as the replacement frequency and associated costs are lower. The membrane lifetime varied from 1 to 10 years, with 5 years as the base value. Beyond a certain lifetime value, the effect on the LCOS diminishes due to less contribution from the membrane cost towards the LCOS. Even if the pervaporation-based process has a higher LCOS than the benchmark, a combination of the aforementioned parameters may make the pervaporation-based process more attractive. However, achieving an optimum combination for some solvent systems may be practically impossible. Due to the absence of membranes in benchmark cases, the membrane-related parameters (permeate flux, membrane price, and lifetime) have no role, and thus they are represented as dotted lines in figures indicating the benchmark LCOS.

The steam price varied from €0 to €35/t, with €35/t as the base value, while the cooling water price varied from €0 to €0.35/m3 with €0.32/m3 as the base value. Higher steam and cooling water prices increase the LCOS due to higher operational costs. Steam production was assumed to come from a gas-fired boiler, making it dependent on the highly variable natural gas (NG) market price. Consequently, processes that rely more on electricity and less on thermal energy are preferred. The processes with fewer or no distillation columns are less affected by steam and cooling water prices due to their lower consumption. In contrast, processes with two or more distillation columns use more steam and cooling water, making them more sensitive to price fluctuations.

For the IPA-water system, at a feed flow rate of around 100 kg/h, the benchmark AD process outperforms pervaporation-based cases. However, such low flow rates may not be practical and economically feasible due to increased heat losses and operational challenges. For a permeate flux below 10 kg/h/m2, the benchmark AD process shows a lower LCOS than the D-PV-D and PV processes. The D-PV process has a lower LCOS than the benchmark AD process at all flux values. When the membrane module price exceeds 120% of the base value, only the D-PV-D process shows slightly higher LCOS than the benchmark AD process. The D-PV and PV processes show lower LCOS at all considered membrane module prices. The D-PV-D and PV processes require membrane lifetimes above 3 and 1.5 years, respectively, to be economically better than the benchmark AD process. For the ACN-water system, permeate flux and membrane lifetime are key parameters. The permeate flux needs to be above 4, 7, and 10 kg/h/m2 for the D-PV, D-PV-D, and PV processes, respectively, to be economical. The membrane lifetime needs to be above 1 year for all pervaporation-based processes to be economical.

For the THF-water system, only the PV process requires the feed flow rate to be above 500 kg/h to outperform the benchmark PSD process. The permeate flux needs to be above 5, 10, and 25 kg/h/m2 for the D-PV, D-PV-D, and PV processes, respectively, to be economical. The membrane module price needs to be below 80%, 90%, and 140% of the base value for the PV, D-PV, and D-PV-D processes, respectively, to be economical. Similarly, the membrane lifetime needs to be above 4 years for all pervaporation-based processes to be more economical than the benchmark PSD process. Steam and cooling water prices are important only for the D-PV-D process, as it involves two distillation columns. For the ACA-water system, only the standalone PV process has the potential to outperform the benchmark ED process. The feed flow rate needs to be below 500 kg/h, the permeate flux above 10 kg/h/m2, the membrane module price below 90% of the base value, and the membrane lifetime above 6 years for it to be economical. For the NMP-water system, none of the pervaporation-based processes show lower LCOS than the benchmark VD process. However, a combination of suitable permeate flux, membrane module price, and membrane lifetime values could potentially result in lower LCOS.

3.5. Environmental Performance

Table 10 presents the annual CO

2 emissions and emission intensities for four cases in each solvent system. The reduction in CO

2 emissions is primarily attributed to decreased steam and cooling water consumption. For the IPA-water, ACN-water, and THF-water systems, all pervaporation-based cases demonstrate significant reductions in CO

2 emissions compared to their respective benchmark processes. The standalone PV case is the most effective, followed by the D-PV case, with the D-PV-D case showing the least reduction in CO

2 emissions. In the ACA-water system, the standalone PV case achieves an 82% reduction in CO

2 emissions compared to the benchmark ED case. The D-PV and D-PV-D cases exhibit similar or increased CO

2 emissions, respectively. For the NMP-water system, the standalone PV case results in a 65% reduction in CO

2 emissions compared to the benchmark VD process. However, the D-PV and D-PV-D cases show significant increases in CO

2 emissions due to higher energy consumption.

3.6. Discussion

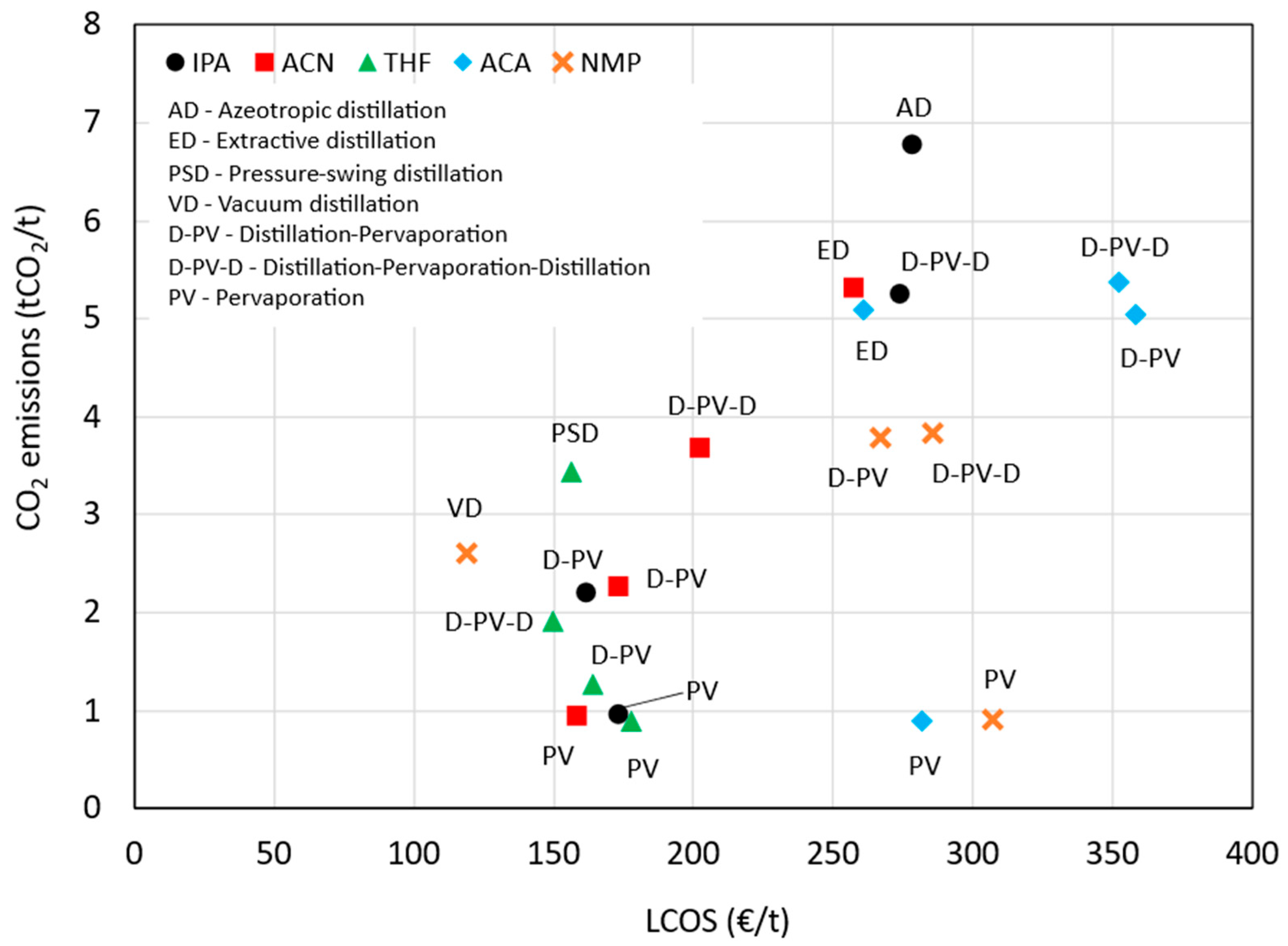

Figure 11 illustrates the comparison of the benchmark and pervaporation-based processes across all five solvent systems, highlighting their respective LCOS and CO

2 emissions. The PV case generally has a lower LCOS compared to the benchmark and D-PV case, except for THF and ACA, where the LCOS are slightly higher. The D-PV case shows a significant cost reduction for IPA and ACN compared to the benchmark. The PV case consistently shows the lowest emissions across all solvent systems. The D-PV case also shows reduced emissions compared to the benchmark, but not as low as the PV case. The D-PV-D method shows variable LCOS relative to the benchmark and generally has higher emissions, except for THF. Overall, the PV method appears to be the most efficient in terms of both cost and emissions across all solvents, while the D-PV method also shows notable improvements over the benchmark.

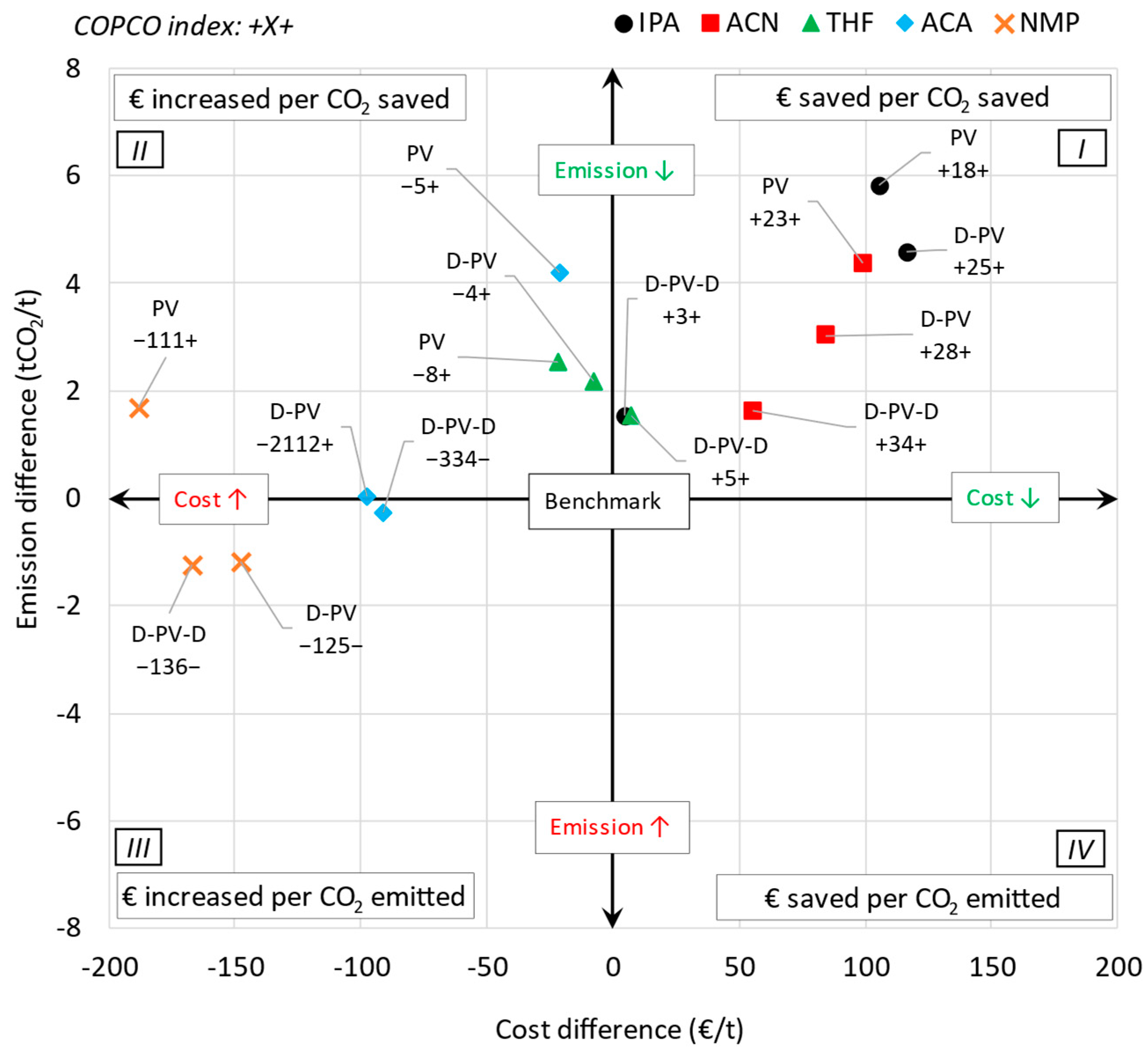

Figure 12 shows the mapping of the COPCO index of all the cases investigated. The

x-axis represents the LCOS difference, while the

y-axis represents the emission difference between a benchmark and a pervaporation-based process, with the origin representing the benchmark process. The labels represent the COPCO index, where the preceding sign indicates cost savings (+) or increases (−), and the succeeding sign indicates emissions reductions (+) or increases (−). Quadrant 1 (top right), with both LCOS and emission difference as positive, represents cases where both LCOS and emissions have decreased compared to the benchmark. Quadrant 2 (top left), with LCOS difference as negative and emission difference as positive, represents cases where LCOS has increased but emissions have decreased compared to the benchmark. Similarly, quadrant 3 (bottom left), with both LCOS and emission difference as negative, represents cases where both LCOS and emissions have increased compared to the benchmark. Lastly, quadrant 4 (bottom right), with LCOS difference as positive and emission difference as negative, represents cases where LCOS has decreased but emissions have increased compared to the benchmark.

The figure shows that for the IPA and ACN systems, all pervaporation-based cases fall in Quadrant 1. For the THF system, the D-PV and PV cases fall in Quadrant 2, but very close to Quadrant 1, while the D-PV-D case falls in Quadrant 1. Similarly, for the ACA system, the D-PV and PV cases fall in Quadrant 2, with the D-PV-D case falling in Quadrant 3, very close to Quadrant 2. For the NMP system, only the PV case falls in Quadrant 2, while the other cases fall in Quadrant 3. None of the investigated cases fall in Quadrant 4.

Recovering used solvents instead of purchasing virgin solvents is crucial for both cost savings and reducing CO2 emissions. Reclaiming solvents on-site can significantly lower the expenses associated with buying new solvents. The cost of purchasing virgin solvents can be quite high, and by recycling used solvents, companies can cut down on these recurring costs. Disposing of spent solvents can be expensive due to hazardous waste regulations. Recycling solvents reduces the volume of waste that needs to be managed and disposed of, leading to further cost savings. The process of recovering used solvents, especially dehydration, typically generates significantly lower CO2 emissions compared to producing virgin solvents from raw materials. Recycling solvents often requires less energy than producing new solvents, which further contributes to reducing the overall carbon footprint of the process. By recovering used solvents, industries can achieve substantial economic benefits while also contributing to environmental sustainability by lowering their carbon emissions. This approach supports the circular economy and helps in minimizing the environmental impact of industrial processes.

Figure 13 shows the relative comparison of cost and CO

2 emissions between the virgin solvent and the recovered (dehydration) solvent using the benchmark (traditional distillation processes) and the best pervaporation-based processes. The market price [

82,

83,

84,

85,

86] and the emission intensity [

87] of the virgin solvents are given in

Table S47 of the

Supplementary Information. The emission intensities were extracted from the ecoinvent database 3.9.1 as implemented in Simapro 7.3.3 [

82]. The cost savings are calculated compared to the solvent market price, while the emission savings are calculated compared to the emissions emanating from the virgin solvent production process.

The results demonstrate the significant cost savings achieved by using pervaporation-based processes compared to traditional distillation methods and purchasing virgin solvents. These savings underscore the economic advantages of solvent recovery, making it a more sustainable and cost-effective option for industries. The results also demonstrate the environmental advantages of using pervaporation-based processes for solvent recovery. These processes generally result in lower CO2 emissions compared to traditional distillation methods and purchasing virgin solvents, highlighting their potential for reducing the industry’s carbon footprint.

All pervaporation-based processes show substantial cost savings compared to purchasing virgin solvents. The D-PV process for IPA saves €1568/t, and the PV process for ACN saves €1312/t. The recovery processes for THF (both PSD and D-PV-D) show the highest cost savings, with up to €1868/t. The savings for ACA are relatively lower compared to other solvents due to the lower market price of ACA. The VD process for NMP shows significant savings of €1381/t, while the D-PV process saves €1233/t. This indicates that a lot of improvements are required in the D-PV process to be able to recover NMP more cost-effectively than the VD process.

Traditional distillation methods (AD, ED, PSD, VD) generally show higher CO2 emissions compared to pervaporation-based processes. The AD process for IPA has emissions of 6.8 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of solvent, while D-PV has only 2.2 tonnes. Pervaporation-based processes (D-PV, PV, D-PV-D) show significant reductions in CO2 emissions. The PV process for ACN reduces emissions to 0.9 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of solvent, compared to 5.3 tonnes for ED. The D-PV-D process for THF shows a notable reduction in emissions (1.9 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of solvent) compared to the virgin solvent (5.9 tonnes). Some processes show minimal or no savings in CO2 emissions. The D-PV process for NMP has emissions of 3.8 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of solvent, which is slightly lower than the virgin solvent emissions (4.1 tonnes).

4. Conclusions

This study presented quantitative insights on the economic and environmental benefits of replacing the traditional distillation processes with pervaporation-based processes for five industrially relevant solvents, namely isopropanol, acetonitrile, tetrahydrofuran, acetic acid, and n-methyl-2-pyrrolidone. For the IPA-water system, the D-PV process leads to a 42% reduction in the LCOS, mainly from a significant reduction in operating costs (energy cost) compared to AD. Similarly, for the ACN-water system, the standalone PV process has moderate capital costs and the lowest operating costs, resulting in a 39% LCOS reduction, making it the most cost-effective for ACN dehydration. The hybrid D-PV-D process is the most cost-effective option for THF dehydration, with a 4% LCOS reduction compared to PSD. For the ACA-water system, the standalone PV process shows a 9% increase over the benchmark ED process due to the highest capital cost resulting from the pervaporation module. Among pervaporation-based processes, only the standalone PV process can outperform the benchmark ED process under specific conditions. For the NMP-water system, pervaporation-based processes (D-PV, D-PV-D, and PV) have higher LCOS due to high costs, with D-PV being the most interesting and standalone PV the least interesting. None of these processes shows lower LCOS than the benchmark VD process, but suitable conditions (permeate flux and membrane module price) could potentially lower the LCOS.

The CO2 emissions reduction is mainly due to decreased steam and cooling water use. For IPA-water, ACN-water, and THF-water systems, all pervaporation-based cases show significant CO2 reductions compared to the benchmarks, with standalone PV being the most effective. In the ACA-water system, standalone PV achieves an 82% CO2 reduction compared to the benchmark ED case. For the NMP-water system, standalone PV results in a 65% CO2 reduction, while D-PV and D-PV-D show increased emissions due to higher energy use.

The study highlights significant cost and environmental benefits of pervaporation-based processes over traditional distillation and virgin solvent purchase, making solvent recovery more sustainable and cost-effective. These processes generally lower CO2 emissions, reducing the industry’s carbon footprint. The results support replacing, debottlenecking, or intensifying traditional distillation-based solvent recovery in chemical, pharmaceutical, and related industries, benefiting both industries and society by reducing energy consumption and emissions.