The Advent of MXene-Based Synthetics and Modification Approaches for Advanced Applications in Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Types of MXene-Based Membranes

1.1.1. Nanostructured Membranes

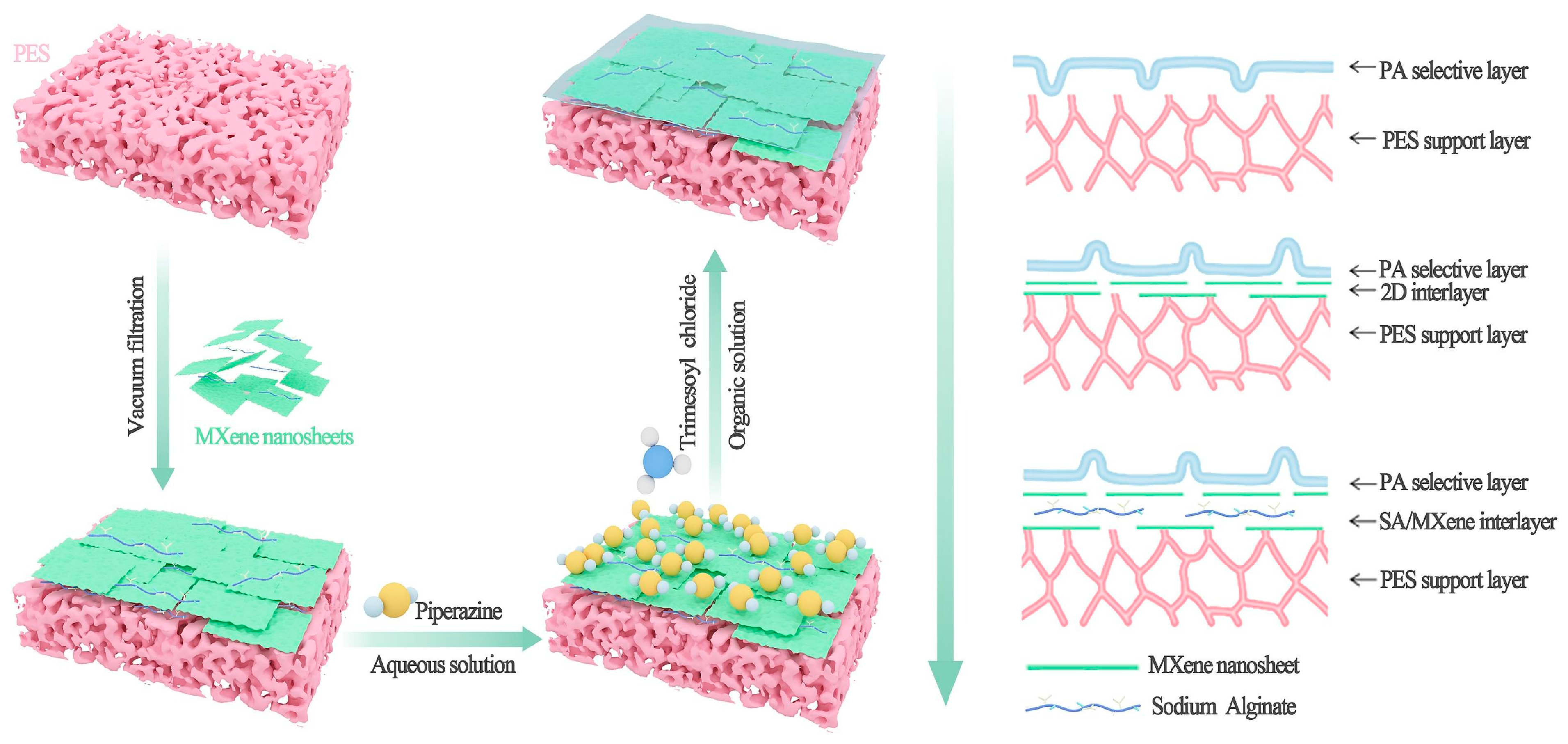

1.1.2. Thin-Film Nanocomposites

1.1.3. Mixed Matrix Membranes

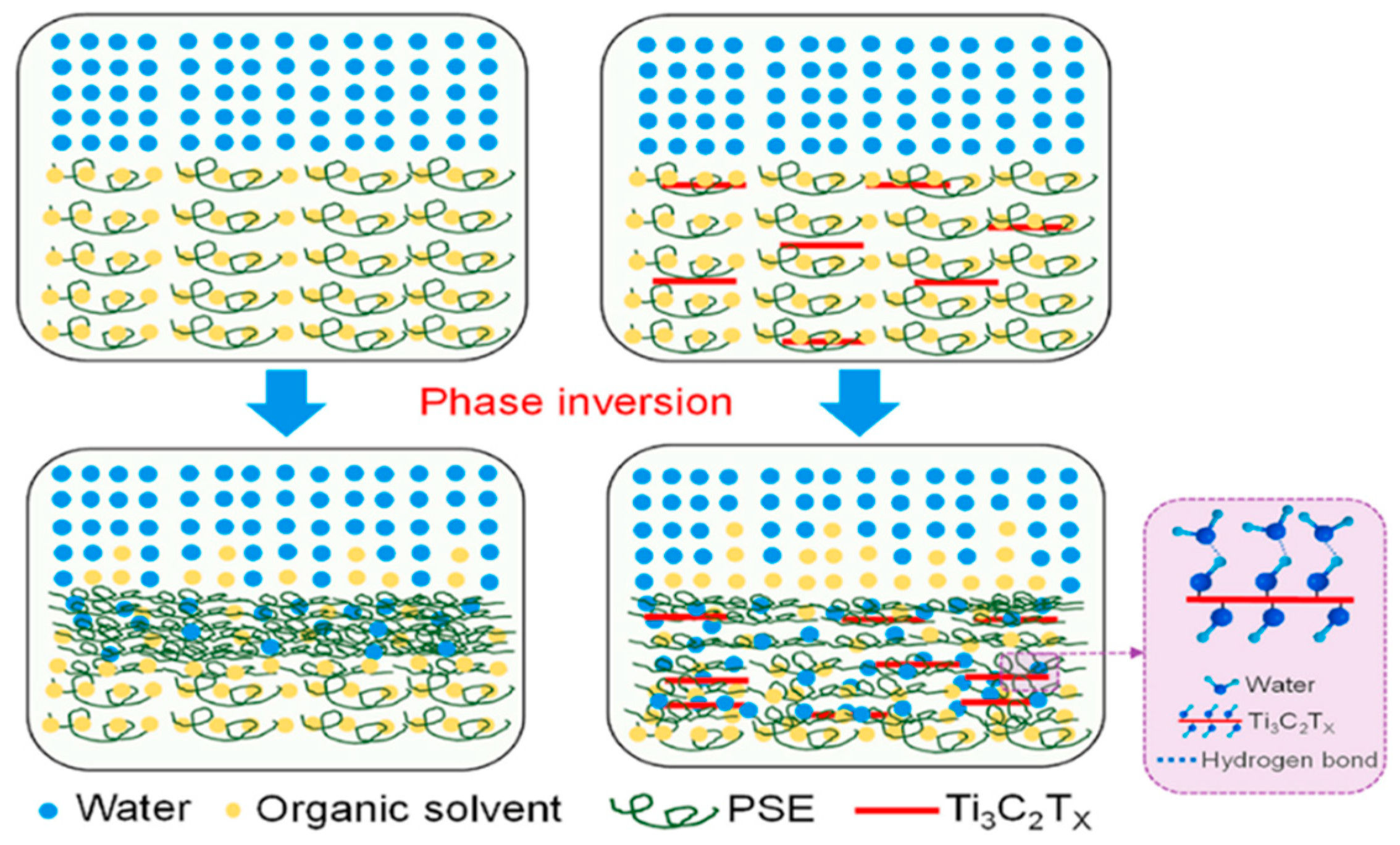

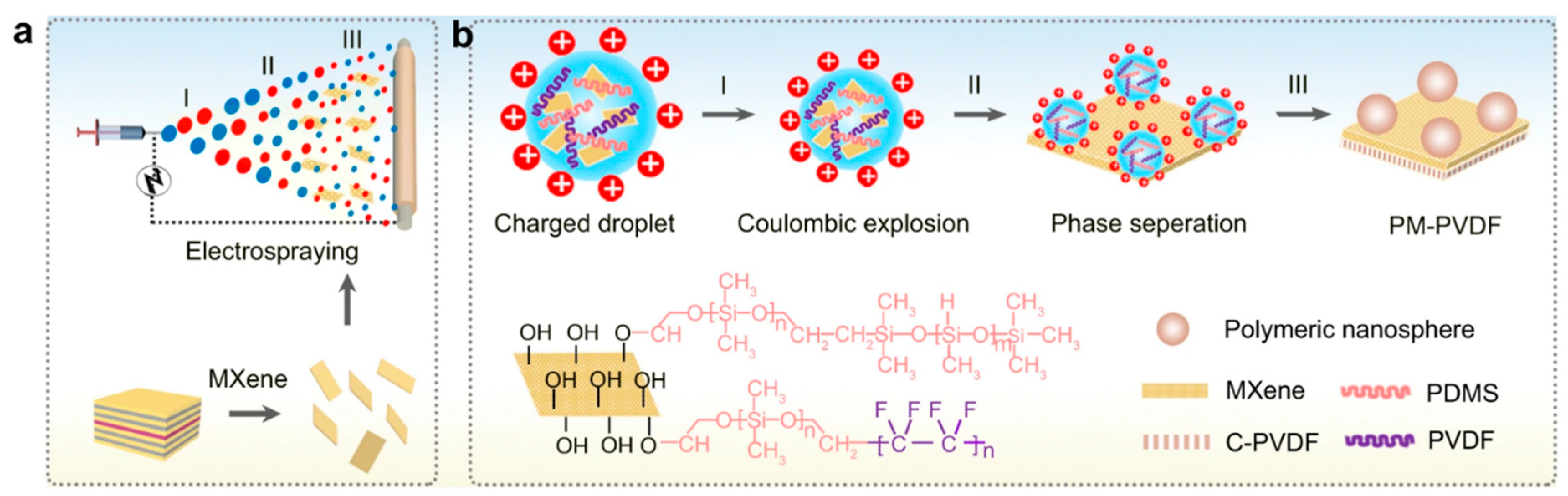

1.2. Fabrication Methods of MXene-Based Polymeric Membranes

2. Applications of MXene-Based Membranes in Water Treatment Methods

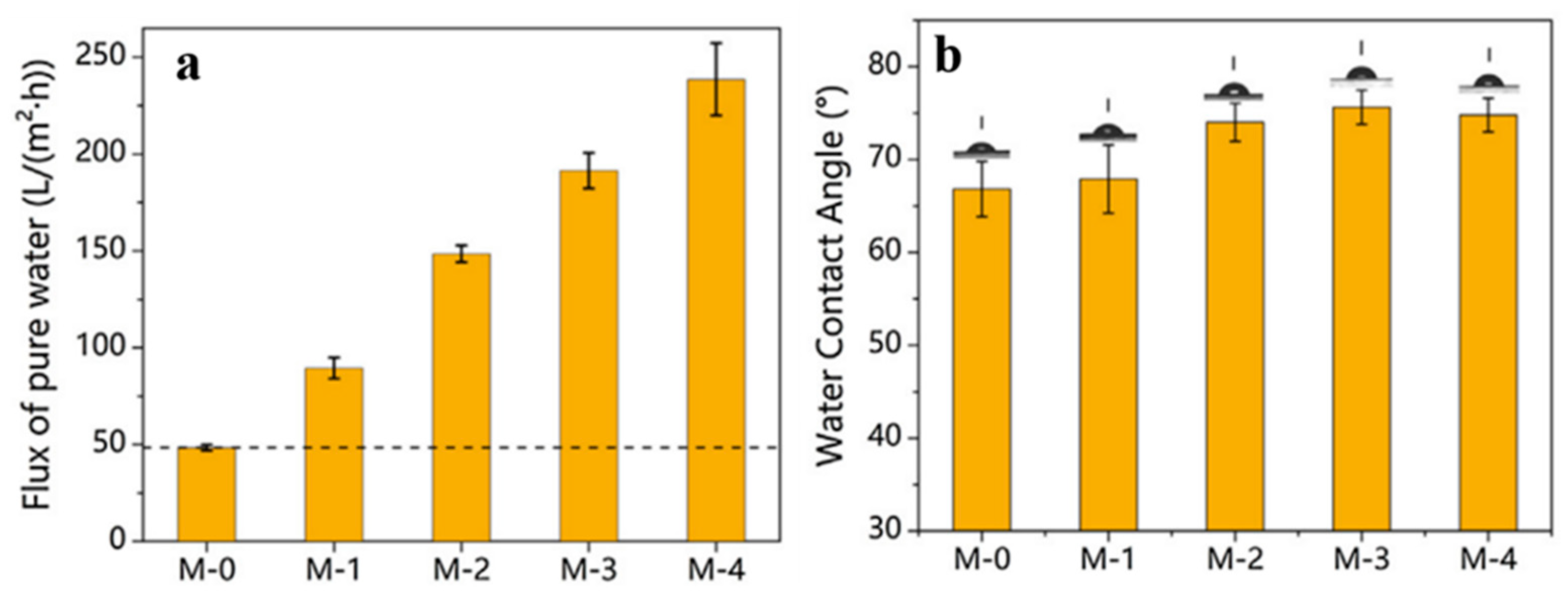

2.1. Ultrafiltration

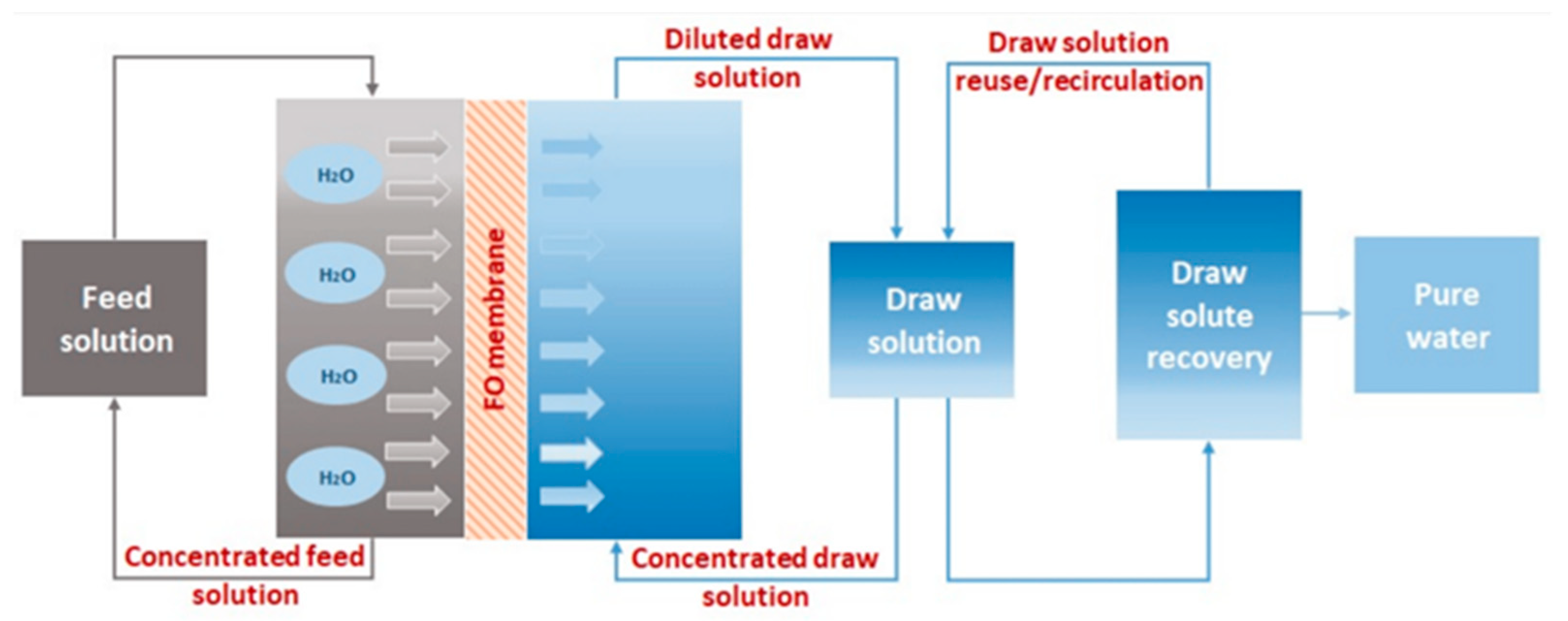

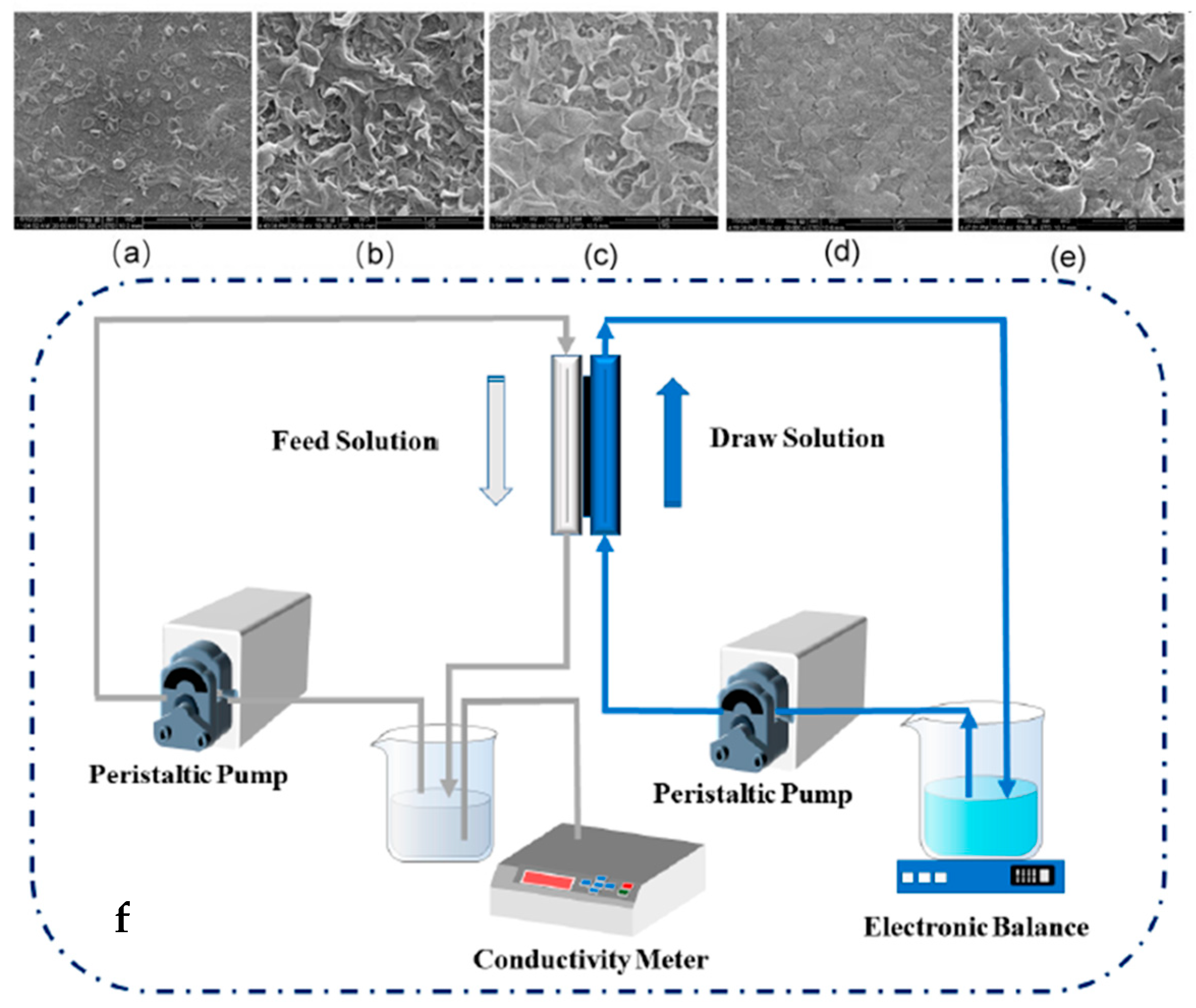

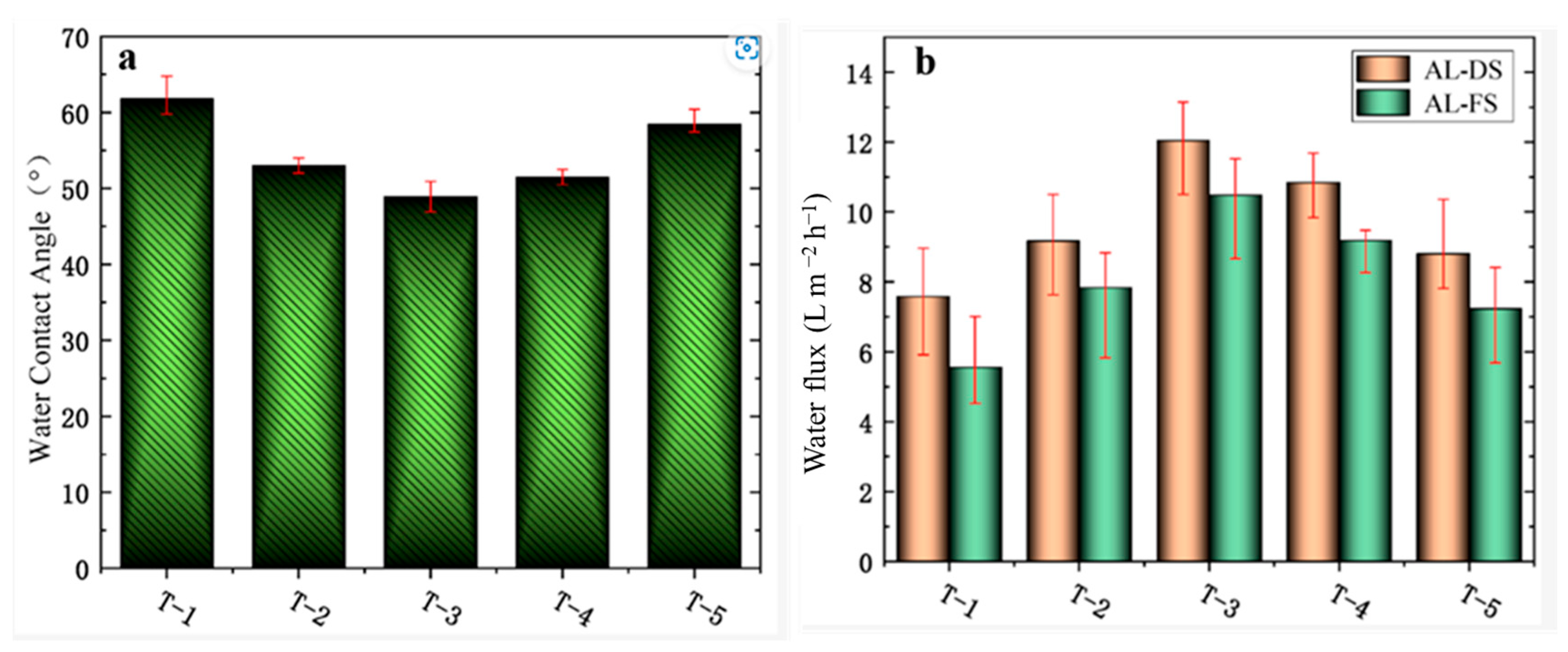

2.2. Forward Osmosis

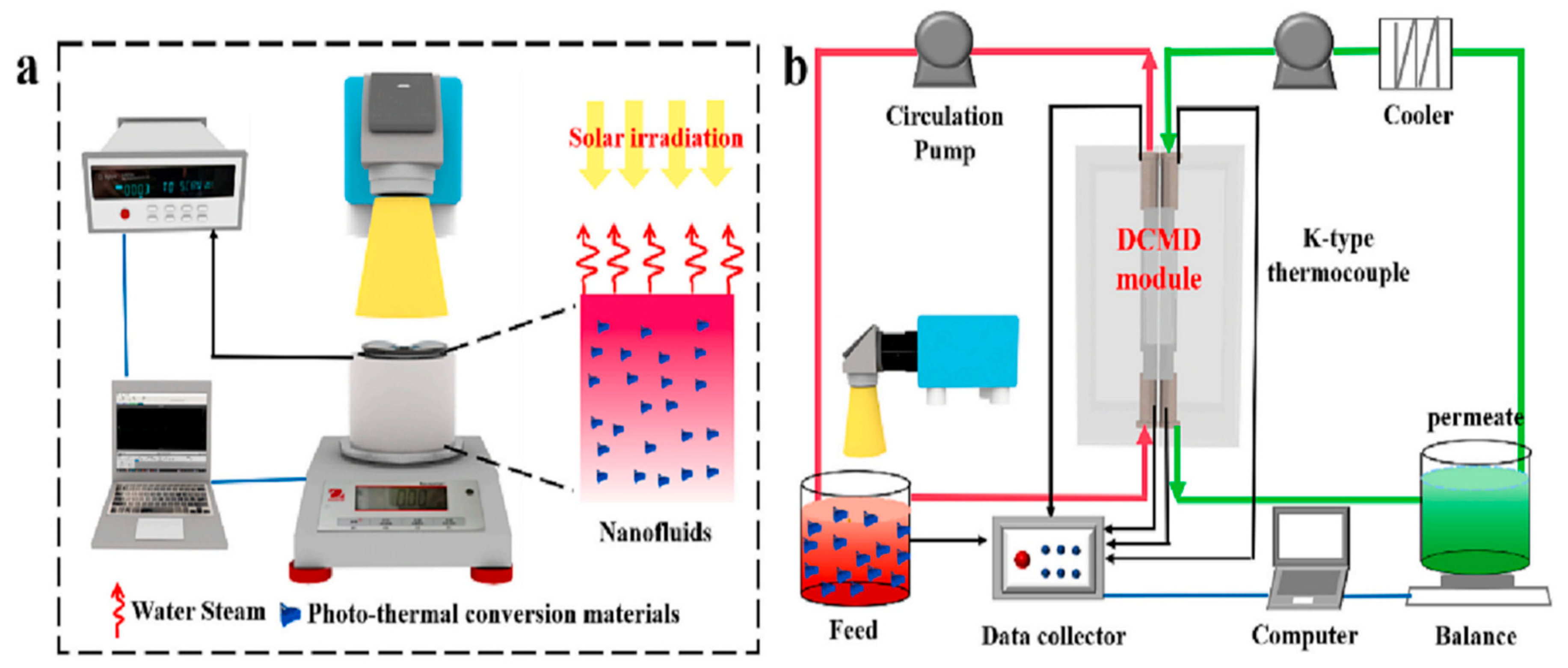

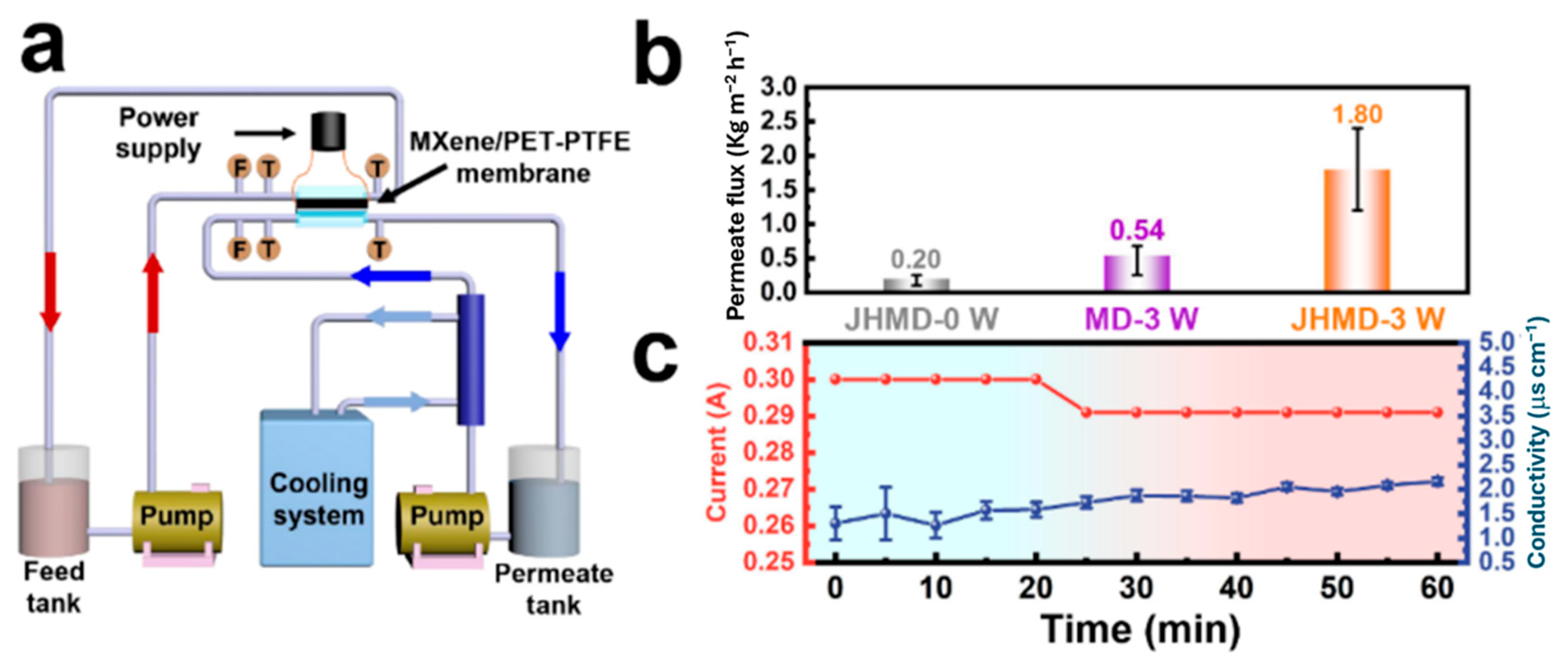

2.3. Membrane Distillation

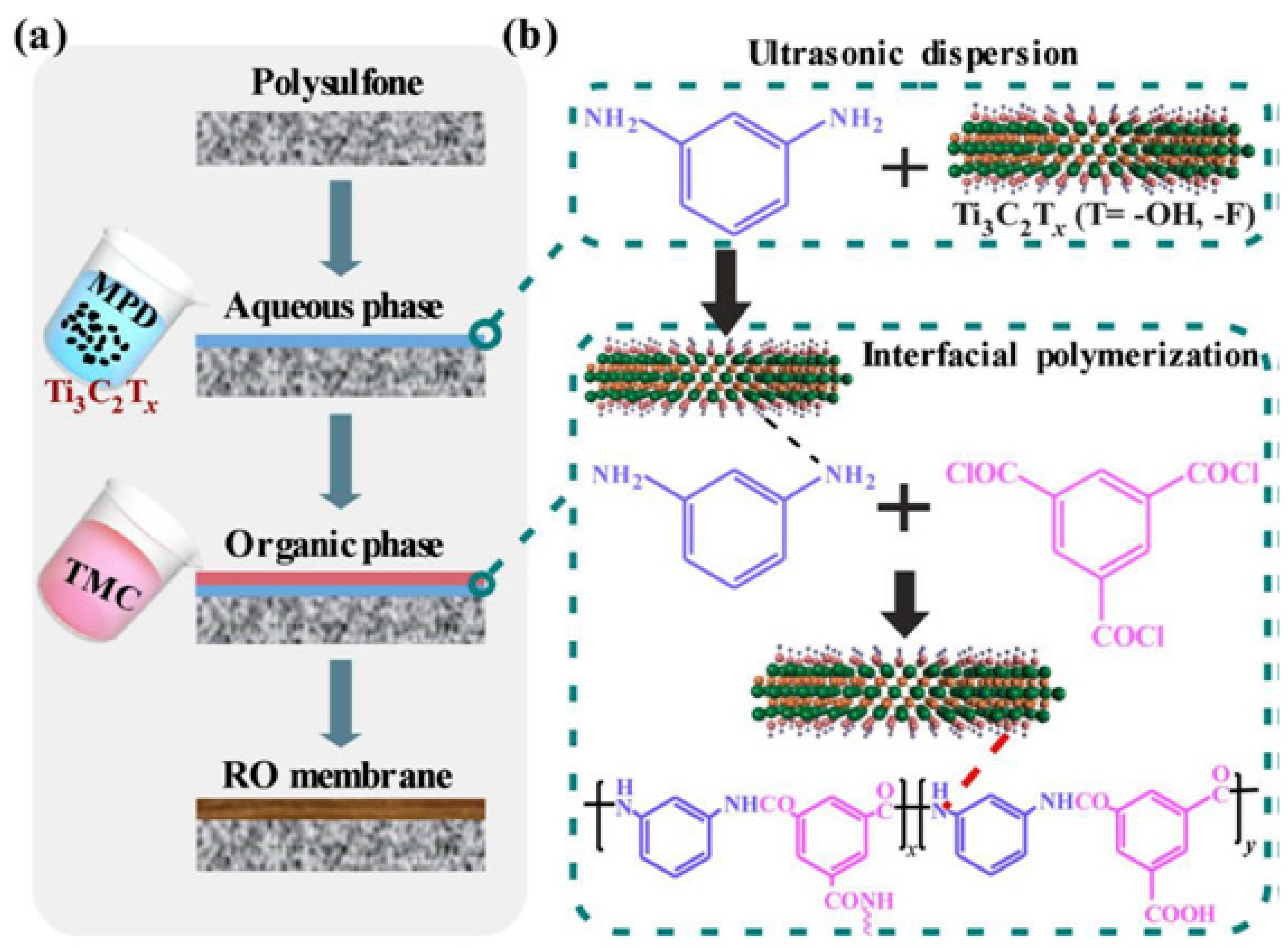

2.4. Reverse Osmosis

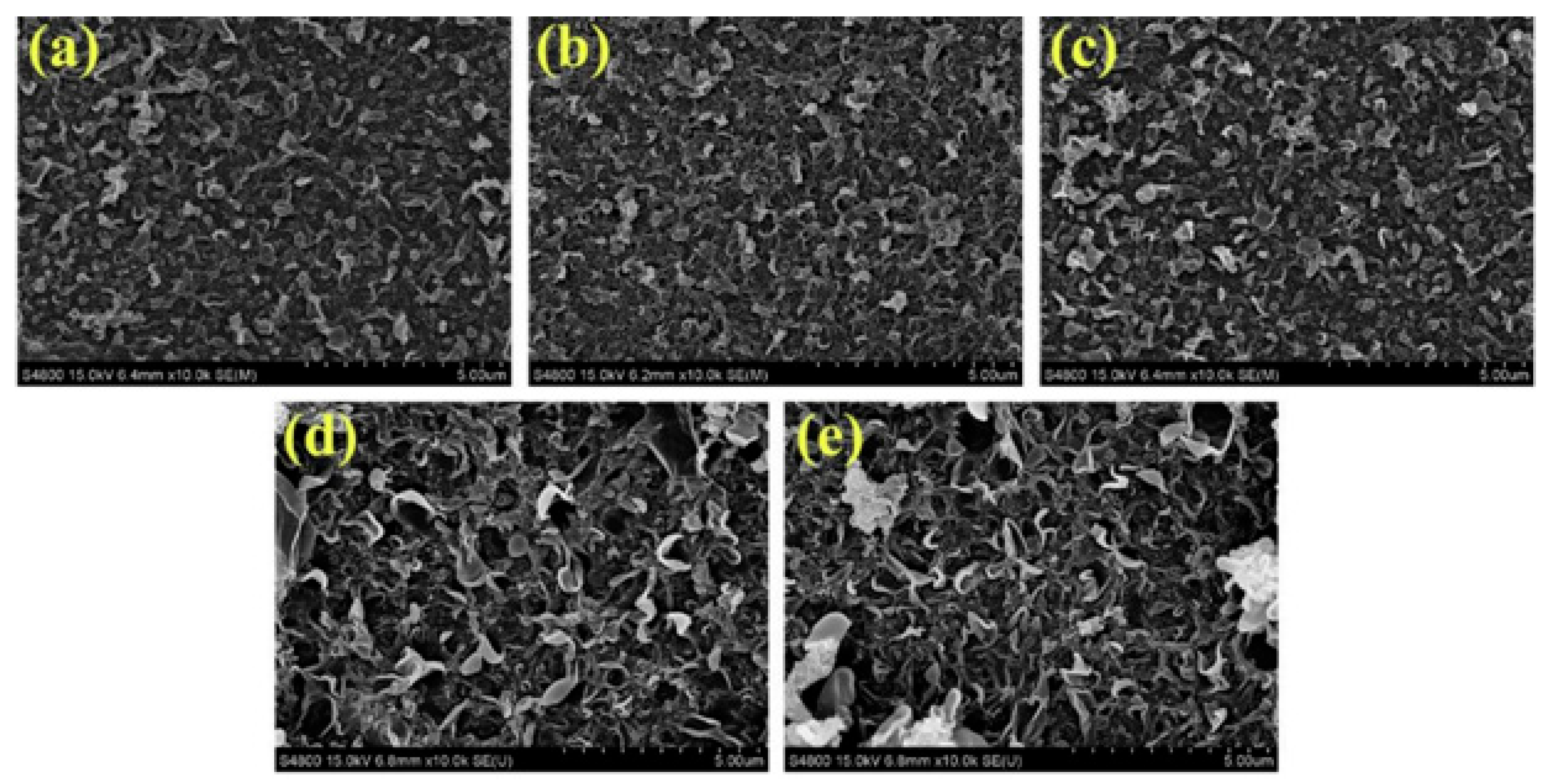

2.5. Nanofiltration

3. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Subramani, A.; Jacangelo, J.G. Emerging Desalination Technologies for Water Treatment: A Critical Review. Water Res. 2015, 75, 164–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Darwish, N.; Hilal, N. Membrane Distillation: A Comprehensive Review. Desalination 2012, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hering, J.G.; Maag, S.; Schnoor, J.L. A Call for Synthesis of Water Research to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6122–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gude, V.G. Desalination and Sustainability—An Appraisal and Current Perspective. Water Res. 2016, 89, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, I.; Sengur, R.; Turken, T.; Guclu, S.; Pasaoglu, M.E. Advances in Water Treatment by Microfiltration, Ultrafiltration, and Nanofiltration. In Advances in Membrane Technologies for Water Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 83–128. [Google Scholar]

- Vishali, S.; Kavitha, E. Application of Membrane-Based Hybrid Process on Paint Industry Wastewater Treatment. In Membrane-Based Hybrid Processes for Wastewater Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Salam, M.H. Membrane Techniques. Applications of Reverse Osmosis. In Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 3833–3837. [Google Scholar]

- Das, R.; Vecitis, C.D.; Schulze, A.; Cao, B.; Ismail, A.F.; Lu, X.; Chen, J.; Ramakrishna, S. Recent Advances in Nanomaterials for Water Protection and Monitoring. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 6946–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, L.; Peng, J.; Zhai, M.; Shi, W. Efficient Thorium(IV) Removal by Two-Dimensional Ti2CTx MXene from Aqueous Solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 366, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.K.; Bhadu, G.R.; Upadhyay, P.; Kulshrestha, V. Three-Dimensional Ni/Fe Doped Graphene Oxide@MXene Architecture as an Efficient Water Splitting Electrocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 41772–41782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-Y.; Akuzum, B.; Kurra, N.; Zhao, M.-Q.; Alhabeb, M.; Anasori, B.; Kumbur, E.C.; Alshareef, H.N.; Ger, M.-D.; Gogotsi, Y. All-MXene (2D Titanium Carbide) Solid-State Microsupercapacitors for on-Chip Energy Storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2847–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Deng, J.; Ding, L.; Li, Z.-K.; Wang, H. Self-Crosslinked MXene (Ti3C2Tx) Membranes with Good Antiswelling Property for Monovalent Metal Ion Exclusion. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 10535–10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, F.; Munoz, G.; Mirzaei, M.; Barbeau, B.; Liu, J.; Duy, S.V.; Sauvé, S.; Kandasubramanian, B.; Mohseni, M. Removal of Zwitterionic PFAS by MXenes: Comparisons with Anionic, Nonionic, and PFAS-Specific Resins. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6212–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Deng, J.; Wei, Y.; Caro, J.; Wang, H. Effective Ion Sieving with Ti3C2Tx MXene Membranes for Production of Drinking Water from Seawater. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.P.; Soon, C.F.; Al-Gheethi, A.A.; Morsin, M.; Tee, K.S. Recent Progress and New Perspective of MXene-Based Membranes for Water Purification: A Review. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 16477–16491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Rouhani, H.; Wang, D.; Zhao, D. Two-Dimensional-Materials Membranes for Gas Separations. In Two-Dimensional-Materials-Based Membranes: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 31, pp. 173–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Caro, J.; Wang, H. A Two-Dimensional Lamellar Membrane: MXene Nanosheet Stacks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 1825–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.E.; Alhabeb, M.; Byles, B.W.; Zhao, M.-Q.; Anasori, B.; Pomerantseva, E.; Mahmoud, K.A.; Gogotsi, Y. Voltage-Gated Ions Sieving through 2D MXene Ti3C2Tx Membranes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 3644–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Kota, S.; Hu, C.; Barsoum, M.W. On the Synthesis of Low-Cost, Titanium-Based Mxenes. J. Ceram. Sci. Technol. 2016, 7, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.L.; Fang, C.; Zhou, F.; Song, Z.; Liu, Q.; Qiao, R.; Yu, M. Self-Assembly: A Facile Way of Forming Ultrathin, High-Performance Graphene Oxide Membranes for Water Purification. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 2928–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Xue, J.; Ding, L.X.; Wang, S.; Caro, J.; Gogotsi, Y. MXene Molecular Sieving Membranes for Highly Efficient Gas Separation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, L.; Natu, V.; Carey, M.; Barsoum, M.W. MXenes: An Introduction of Their Synthesis, Select Properties, and Applications. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloub, A.; Kujawski, W. Recent Advances in Polymeric Membrane Integration for Organic Solvent Mixtures Separation: Mini-Review. Membranes 2025, 30, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.M.; Kim, D.W.; Ren, C.E.; Cho, K.M.; Kim, S.J.; Choi, J.H.; Nam, Y.T.; Gogotsi, Y.; Jung, H.-T. Selective Molecular Separation on Ti3C2Tx–Graphene Oxide Membranes during Pressure-Driven Filtration: Comparison with Graphene Oxide and MXenes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 44687–44694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, R.; Hong, H.; Shen, L.; Lin, H.; Liao, B.-Q. Enhanced Permeability and Antifouling Performance of Polyether Sulfone (PES) Membrane via Elevating Magnetic Ni@MXene Nanoparticles to Upper Layer in Phase Inversion Process. J. Memb. Sci. 2021, 623, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, K.; Mahmoud, K.A.; Johnson, D.J.; Helal, M.; Berdiyorov, G.R.; Gogotsi, Y. Efficient Antibacterial Membrane Based on Two-Dimensional Ti3C2Tx (MXene) Nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, G.; Ye, H.; Jin, W.; Cui, Z. Two-Dimensional MXene Incorporated Chitosan Mixed-Matrix Membranes for Efficient Solvent Dehydration. J. Memb. Sci. 2018, 563, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.; Teng, D.; Xie, Y.; Luan, Q. Preparation and Application of P84 Copolyimide/GO Mixed Matrix Membrane with Improved Permselectivity and Solvent Resistance. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 167, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, S.; Anjum, D.H.; Luo, S.; Abbas, Y.; Li, B.; Iqbal, S.; Liao, K. 2D Ti3C2Tx MXene Nanosheets Coated Cellulose Fibers Based 3D Nanostructures for Efficient Water Desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouzaam, A.; Qiblawey, H. Functional GO-Based Membranes for Water Treatment and Desalination: Fabrication Methods, Performance and Advantages. A Review. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazinani, S.; Darvishmanesh, S.; Ehsanzadeh, A.; Van der Bruggen, B. Phase Separation Analysis of Extem/Solvent/Non-Solvent Systems and Relation with Membrane Morphology. J. Memb. Sci. 2017, 526, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, D.H.N.; Song, Q.; Qiblawey, H.; Sivaniah, E. Regulating the Aqueous Phase Monomer Balance for Flux Improvement in Polyamide Thin Film Composite Membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 2015, 487, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Li, P.; Zhou, A.; Cao, X.; Hu, Q. Preparation, Mechanical and Anti-Friction Performance of MXene/Polymer Composites. Mater. Des. 2016, 92, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Habib, T.; Shah, S.; Gao, H.; Radovic, M.; Green, M.J.; Lutkenhaus, J.L. Surface-Agnostic Highly Stretchable and Bendable Conductive MXene Multilayers. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaaq0118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, H.; Habib, T.; Shah, S.; Gao, H.; Patel, A.; Echols, I.; Zhao, X.; Radovic, M.; Green, M.J.; Lutkenhaus, J.L. Water Sorption in MXene/Polyelectrolyte Multilayers for Ultrafast Humidity Sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.E.; Lalia, B.S.; Hashaikeh, R. A Review on Electrospinning for Membrane Fabrication: Challenges and Applications. Desalination 2015, 356, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Tao, Q.; Liu, X.; Fahlman, M.; Halim, J.; Persson, P.O.Å.; Rosen, J.; Zhang, F. Polymer-MXene Composite Films Formed by MXene-Facilitated Electrochemical Polymerization for Flexible Solid-State Microsupercapacitors. Nano Energy 2019, 60, 734–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Raj, S.K.; Rathod, N.H.; Kulshrestha, V. Polysulfone/Graphene Quantum Dots Composite Anion Exchange Membrane for Acid Recovery by Diffusion Dialysis. J. Memb. Sci. 2020, 611, 118331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, A.; Raj, S.K.; Lebedeva, O.V.; Chesnokova, A.N.; Raskulova, T.V.; Kulshrestha, V. Functionalized Carbon Dots Composite Cation Exchange Membranes: Improved Electrochemical Performance and Salt Removal Efficiency. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 609, 125677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamadani, Y.A.J.; Jun, B.-M.; Yoon, M.; Taheri-Qazvini, N.; Snyder, S.A.; Jang, M.; Heo, J.; Yoon, Y. Applications of MXene-Based Membranes in Water Purification: A Review. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.-Y.; Yin, M.-J.; Wang, Z.-P.; Wang, N.; Qin, Z.; An, Q.-F. Ultralow Ti3C2TX Doping Polysulfate Membrane for High Ultrafiltration Performance. J. Memb. Sci. 2021, 637, 119603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Shen, J.; Ji, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, G.; Yang, J.; Jin, W. Two-Dimensional Ti2CTx MXene Membranes with Integrated and Ordered Nanochannels for Efficient Solvent Dehydration. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2019, 7, 12095–12104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, M.; Arai, M.; Sasaki, T.; Chung, C.; Venkataramanan, N.S.; Estili, M.; Sakka, Y.; Kawazoe, Y. Novel Electronic and Magnetic Properties of Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Carbides and Nitrides. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 2185–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Liu, G.; Ji, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, L.; Guan, K.; Zhang, M.; Liu, G.; Xiong, J.; Yang, J.; et al. 2D MXene Nanofilms with Tunable Gas Transport Channels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1801511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yu, M.; Yoon, Y. Fouling and Retention Mechanisms of Selected Cationic and Anionic Dyes in a Ti3C2Tx MXene-Ultrafiltration Hybrid System. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 16557–16565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Wang, T.; Du, C.-H.; Wang, G.; Wu, L.; Jiang, X.; Guo, H.-C. Construction of PES Mixed Matrix Membranes Incorporating ZnFe2O4@MXene Composites with High Permeability and Antifouling Performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

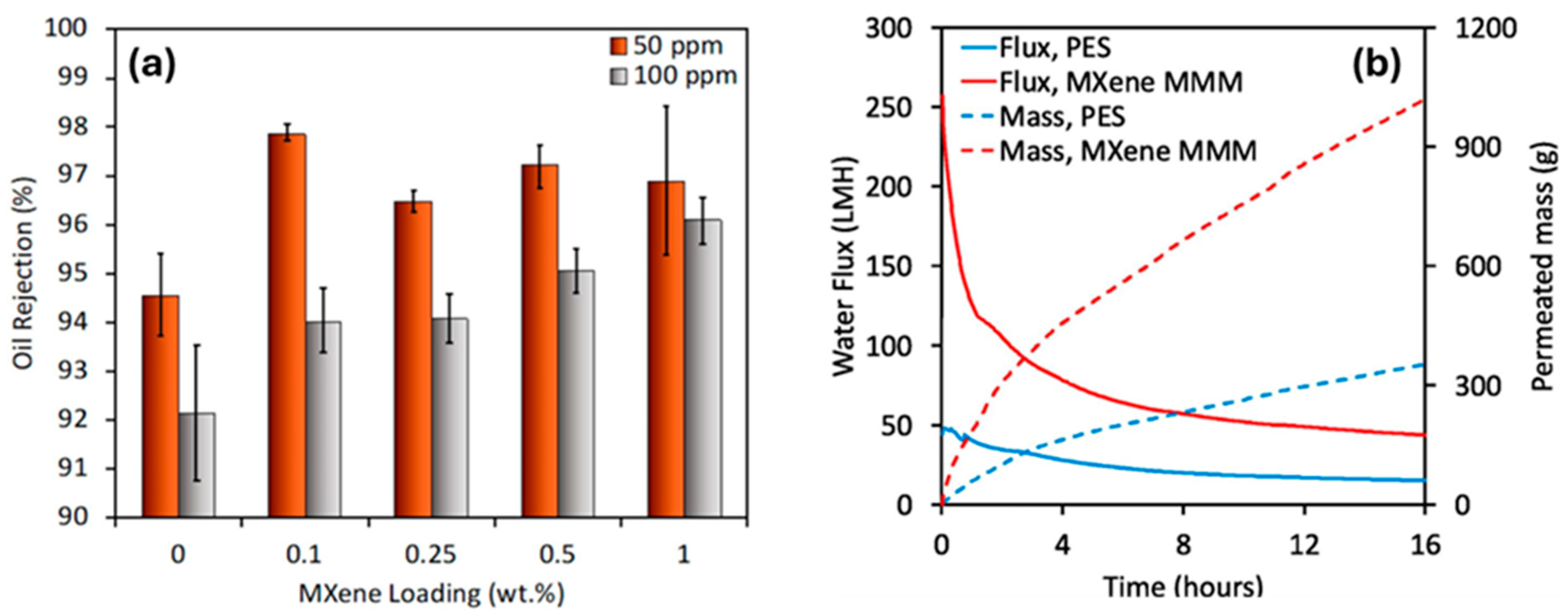

- Nabeeh, A.; Abdalla, O.; Rehman, A.; Ghouri, Z.K.; Abdel-Wahab, A.; Mahmoud, K.; Abdala, A. Ultrafiltration Polyethersulfone-MXene Mixed Matrix Membranes with Enhanced Air Dehumidification and Oil-Water Separation Performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 346, 127285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

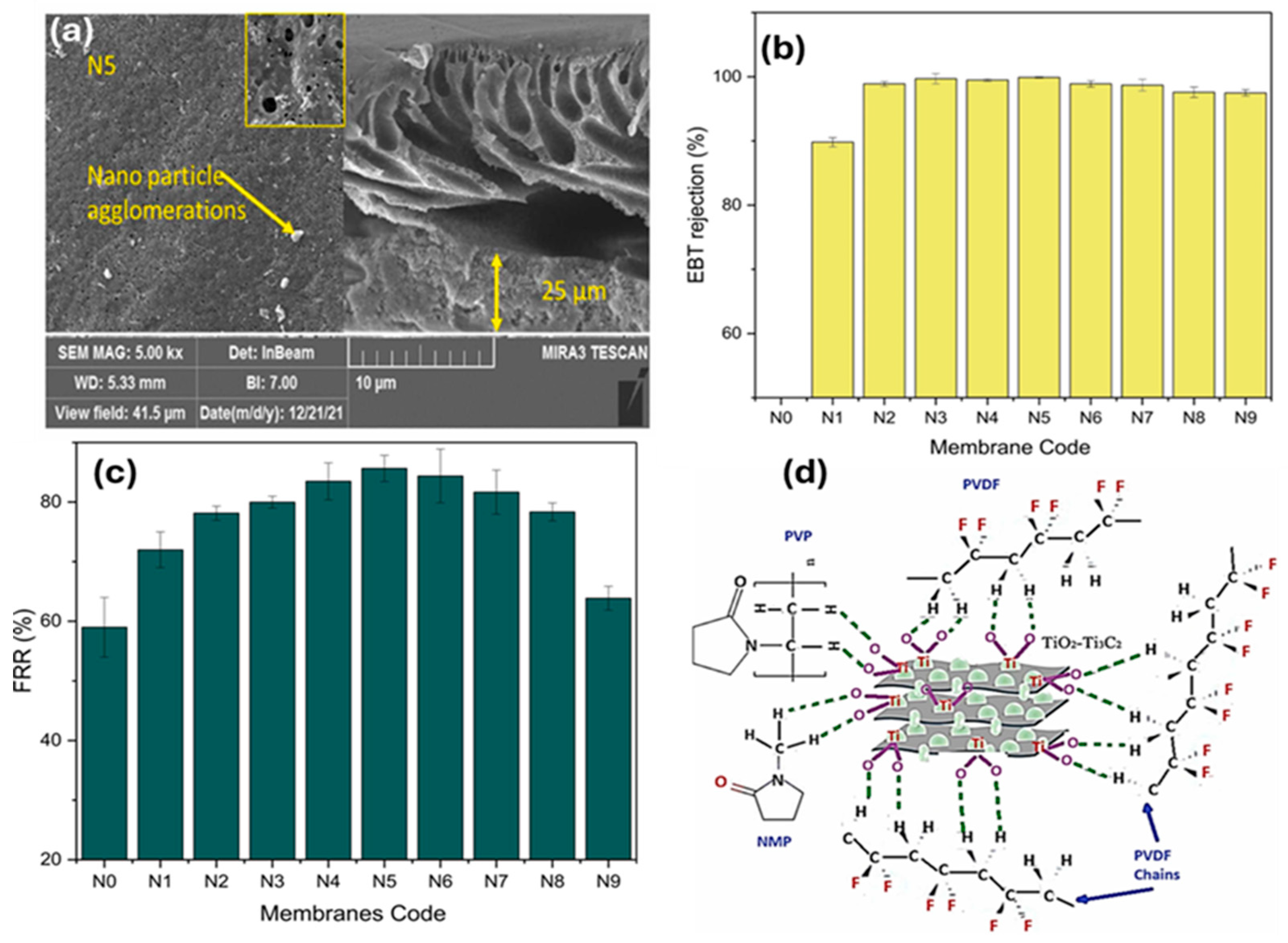

- Abood, T.W.; Shabeeb, K.M.; Alzubaydi, A.B.; Fal, M.; Lotaibi, A.M.A.; Lawal, D.U.; Hernadi, K.; Alsalhy, Q.F. Novel MXene/PVDF Nanocomposite Ultrafiltration Membranes for Optimized Eriochrome Black T (Azo Dye) Removal. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 318, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, B.M.; Al Aani, S.; Alsarayreh, A.A.; Alsalhy, Q.F.; Salih, I.K. Forward Osmosis Membrane: Review of Fabrication, Modification, Challenges and Potential. Membranes 2023, 13, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Lim, Y.J.; Zhang, K. Engineering multi-channel water transport in surface-porous MXene nanosheets for high-performance thin-film nanocomposite membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 728, 124151–124162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.P.; Rasheed, P.A.; Gomez, T.; Azam, R.S.; Mahmoud, K.A. A Fouling-Resistant Mixed-Matrix Nanofiltration Membrane Based on Covalently Cross-Linked Ti3C2TX (MXene)/Cellulose Acetate. J. Memb. Sci. 2020, 607, 118139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfahel, R.; Azzam, R.S.; Hafiz, M.; Hawari, A.H.; Pandey, R.P.; Mahmoud, K.A.; Hassan, M.K.; Elzatahry, A.A. Fabrication of Fouling Resistant Ti3C2Tx (MXene)/Cellulose Acetate Nanocomposite Membrane for Forward Osmosis Application. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 38, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Graham, N.; Yu, W.; Shi, Y.; Sun, K.; Liu, T. Preparation and Evaluation of a High Performance Ti3C2Tx-MXene Membrane for Drinking Water Treatment. J. Memb. Sci. 2022, 654, 120469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Graham, N.; Yu, W.; Sun, K.; Xu, X.; Liu, T. Optimal Cross-Linking of MXene-Based Membranes for High Rejection and Low Adsorption with Long-Term Stability for Water Treatment. J. Memb. Sci. 2024, 701, 122738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhao, P.; Tang, C.Y.; Yi, X.; Wang, X. Preparation of Electrically Enhanced Forward Osmosis (FO) Membrane by Two-Dimensional MXenes for Organic Fouling Mitigation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 3818–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Xie, C.; Wang, Y. Preparation and Characterization of the Forward Osmosis Membrane Modified by MXene Nano-Sheets. Membranes 2022, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, W.; Cao, H. Arginine-Functionalized Thin Film Composite Forward Osmosis Membrane Integrating Antifouling and Antibacterial Effects. Membranes 2023, 13, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, Y.-H.; Sengupta, A.; Chen, S.-T.; Huang, S.-H.; Hu, C.-C.; Hung, W.-S.; Chang, Y.; Qian, X.; Wickramasinghe, S.R.; Lee, K.-R.; et al. Zwitterion Augmented Polyamide Membrane for Improved Forward Osmosis Performance with Significant Antifouling Characteristics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 212, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ge, Q. A Bifunctional Zwitterion That Serves as Both a Membrane Modifier and a Draw Solute for Forward Osmosis Wastewater Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 36118–36129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, C.; He, Y.; Pan, J.; Xu, T. Second Interfacial Polymerization on Polyamide Surface Using Aliphatic Diamine with Improved Performance of TFC FO Membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 2016, 498, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, H.; Verma, A.K.; Dhupper, R.; Wadhwa, S.; Garg, M.C. Development of CA-TiO2-Incorporated Thin-Film Nanocomposite Forward Osmosis Membrane for Enhanced Water Flux and Salt Rejection. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 5387–5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Hua, S.; Zhang, J. MXene-Based Composite Forward Osmosis (FO) Membrane Intercalated by Halloysite Nanotubes with Superior Water Permeance and Dye Desalination Performance. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 180, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.K.; Sathyamurthy, R.; Saidur, R.; Velraj, R.; Lynch, I.; Aslfattahi, N. Exploring the Potential of MXene-Based Advanced Solar-Absorber in Improving the Performance and Efficiency of a Solar-Desalination Unit for Brackish Water Purification. Desalination 2022, 526, 115521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, M.U.; Kharraz, J.A.; Sun, J.; Boey, M.; Riaz, M.A.; Wong, P.W.; Jia, M.; Zhang, X.; Deka, B.J.; Khanzada, N.K.; et al. Advancements in Nanoenabled Membrane Distillation for a Sustainable Water-Energy-Environment Nexus. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2307950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Yu, W.; Lei, H. Novel Solar Membrane Distillation System Based on Ti3C2TX MXene Nanofluids with High Photothermal Conversion Efficiency. Desalination 2022, 539, 115930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wong, P.W.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Jiang, M.; Wang, Z.; An, A.K. Transforming Ti3C2Tx MXene’s Intrinsic Hydrophilicity into Superhydrophobicity for Efficient Photothermal Membrane Desalination. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Ma, L.; He, Y.; Tang, X.; Park, C.B. Sustainable Solar-Driven MXene/Polyvinylidene Fluoride Composite Nanofiber Membrane for Oil/Saltwater Separation and Distillation in the Complex Environment. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Fang, X.; Yu, W.; Xie, H.; Lei, H. Magnetic Recyclable Fe3O4@Ti3C2TX Nanoparticles for High-Efficiency Solar Membrane Distillation. Desalination 2023, 564, 116784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yong, B.; Huang, H.; Yao, L.; Deng, L. Depression of Electro-Oxidation of Ti3C2Tx MXene Joule Heater by Alternating Current for Joule Heating Membrane Distillation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 142149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalash, K.; Kadhom, M.; Al-Furaiji, M. Thin Film Nanocomposite Membranes Filled with MCM-41 and SBA-15 Nanoparticles for Brackish Water Desalination via Reverse Osmosis. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 20, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Elam, J.W.; Darling, S.B. Membrane Materials for Water Purification: Design, Development, and Application. Environ. Sci. 2016, 2, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramono, E.; Umam, K.; Sagita, F.; Saputra, O.A.; Alfiansyah, R.; Setyawati Dewi, R.S.; Kadja, G.T.M.; Ledyastuti, M.; Wahyuningrum, D.; Radiman, C.L. The Enhancement of Dye Filtration Performance and Antifouling Properties in Amino-Functionalized Bentonite/Polyvinylidene Fluoride Mixed Matrix Membranes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlee, L.F.; Lawler, D.F.; Freeman, B.D.; Marrot, B.; Moulin, P. Reverse Osmosis Desalination: Water Sources, Technology, and Today’s Challenges. Water Res. 2009, 43, 2317–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Rui, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z. A Review on Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membranes for Water Purification. Polymers 2019, 11, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; He, M.; Su, Y.; Zhao, X.; Elimelech, M.; Jiang, Z. Antifouling Membranes for Sustainable Water Purification: Strategies and Mechanisms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 5888–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, S.E.; Bar-Zeev, E.; Elimelech, M. Biofouling in Forward Osmosis and Reverse Osmosis: Measurements and Mechanisms. J. Memb. Sci. 2015, 493, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Chen, S.; Peng, X.; Zhang, L.; Gao, C. Polyamide Membranes with Nanoscale Turing Structures for Water Purification. Science 2018, 360, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, K.; Liu, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, N.; Xu, J. Janus-structured MXene-PA/MS with an ultrathin intermediate layer for high-salinity water desalination and wastewater purification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 682, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Dai, X.; Gai, J. Preparation of High-performance Reverse Osmosis Membrane by Zwitterionic Polymer Coating in a Facile One-step Way. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.-Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.S. Hybrid Organic/Inorganic Reverse Osmosis (RO) Membrane for Bactericidal Anti-Fouling. 1. Preparation and Characterization of TiO2 Nanoparticle Self-Assembled Aromatic Polyamide Thin-Film-Composite (TFC) Membrane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 2388–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyki, A.; Rahimpour, A.; Jahanshahi, M. Preparation and Characterization of Thin Film Composite Reverse Osmosis Membranes Incorporated with Hydrophilic SiO2 Nanoparticles. Desalination 2015, 368, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, G.-R. Graphene Oxide (GO) as Functional Material in Tailoring Polyamide Thin Film Composite (PA-TFC) Reverse Osmosis (RO) Membranes. Desalination 2016, 394, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathizadeh, M.; Tien, H.N.; Khivantsev, K.; Song, Z.; Zhou, F.; Yu, M. Polyamide/Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots (N-GOQD) Thin Film Nanocomposite Reverse Osmosis Membranes for High Flux Desalination. Desalination 2019, 451, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Qiu, S.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Gao, C. Improving the Performance of Polyamide Reverse Osmosis Membrane by Incorporation of Modified Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Memb. Sci. 2014, 450, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Huang, H.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y. Novel Thin-Film Reverse Osmosis Membrane with MXene Ti3C2T Embedded in Polyamide to Enhance the Water Flux, Anti-Fouling and Chlorine Resistance for Water Desalination. J. Memb. Sci. 2020, 603, 118036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.L.; Japip, S.; Zhang, Y.; Weber, M.; Maletzko, C.; Chung, T.-S. Emerging Thin-Film Nanocomposite (TFN) Membranes for Reverse Osmosis: A Review. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasid, Z.A.M.; Omar, M.F.; Nazeri, M.F.M.; A’ziz, M.A.A.; Szota, M. Low Cost Synthesis Method of Two-Dimensional Titanium Carbide MXene. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 209, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ding, M.; Xu, H.; Yang, W.; Zhang, K.; Tian, H.; Wang, H.; Xie, Z. Scalable Ti3C2Tx MXene Interlayered Forward Osmosis Membranes for Enhanced Water Purification and Organic Solvent Recovery. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 9125–9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, D.; Zhou, Y.; Nie, W.; Chen, P. Sodium Alginate-Assisted Exfoliation of MoS2 and Its Reinforcement in Polymer Nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 155, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Tian, D.; Zhan, Z.; Lu, C. Ultrathin MXene/Calcium Alginate Aerogel Film for High-Performance Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1802040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geise, G.M.; Park, H.B.; Sagle, A.C.; Freeman, B.D.; McGrath, J.E. Water Permeability and Water/Salt Selectivity Tradeoff in Polymers for Desalination. J. Memb. Sci. 2011, 369, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werber, J.R.; Osuji, C.O.; Elimelech, M. Materials for Next-Generation Desalination and Water Purification Membranes. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, N. Two-dimensional nanomaterials: A critical review of recent progress, properties, applications, and future directions. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 165, 107362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, D.; Xue, H.; Dong, P.; Zhang, J.; Goto, T. Highly permeable and dye-rejective nanofiltration membranes of TiO2 and Bi2S3 double-embedded Ti3C2Tx with a visible-light-induced self-cleaning ability. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 4156–4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Zhuang, X.; Fu, H.; Brunklaus, G.; Forster, M.; Chen, Y.; Feng, X.; Scherf, U. Two-dimensional core-shelled porous hybrids as highly efficient catalysts for the oxygen reduction reaction. Angew. Chem.–Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6858–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, N.; Yu, L.J.; Karton, A.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Guo, F.; Hou, L.; Cheng, Q.; Jiang, L.; et al. Bioinspired graphene membrane with temperature tunable channels for water gating and molecular separation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, D.D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Jing, Y.X.; Cao, X.L.; Zhang, F.; Sun, S.P. Enhancing interfacial adhesion of MXene nanofiltration membranes via pillaring carbon nanotubes for pressure and solvent stable molecular sieving. J. Memb. Sci. 2021, 623, 119033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dai, R.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Z. Aramid nanofiber membranes reinforced by MXene nanosheets for recovery of dyes from textile wastewater. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 6328–6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Xu, H.; Fu, M.; Lin, J.; Ma, T.; Ding, J.; Gao, L. Enhanced high-salinity brines treatment using polyamide nanofiltration membrane with tunable interlayered MXene channel. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 158434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zou, L.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, D. Facile MXene-templated thin film composite membranes for enhanced nanofiltration performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 19, 131680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.P. High-performance PEI-based nanofiltration membrane by MXene-regulated interfacial polymerization reaction: Design, fabrication and testing. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 717, 123568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Membrane Combination | Water Flux (L m−2h−1) | Reverse Salt Flux (g m−2h−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MXene + polyether sulfone + polyvinylpyrrolidone | 12.05 | 8.43 | [56] |

| Arginine + polyether sulfone | 22.7 | 3.1 | [57] |

| n-aminoethyl piperazine propane sulfonate + polyether sulfone | 15 | 5.7 | [58] |

| (1-(3-aminopropyl)-imidazole) propane-sulfonate + polyether sulfone | 22.7 | 3.4 | [59] |

| 2-[(2-aminoethyl) amino]-ethane sulfonic acid monosodium salt + polyether sulfone | 13.5 | 8.8 | [60] |

| Cellulose acetate + TiO2 + polyvinyl pyrrolidone | 58.21 | 16.28 | [61] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soni, I.; Ahuja, M.; Jagtap, P.K.; Chauhan, V.; Raj, S.K.; Sharma, P.P. The Advent of MXene-Based Synthetics and Modification Approaches for Advanced Applications in Wastewater Treatment. Membranes 2025, 15, 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120364

Soni I, Ahuja M, Jagtap PK, Chauhan V, Raj SK, Sharma PP. The Advent of MXene-Based Synthetics and Modification Approaches for Advanced Applications in Wastewater Treatment. Membranes. 2025; 15(12):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120364

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoni, Isha, Monika Ahuja, Pratik Kumar Jagtap, Vinay Chauhan, Savan K. Raj, and Prem P. Sharma. 2025. "The Advent of MXene-Based Synthetics and Modification Approaches for Advanced Applications in Wastewater Treatment" Membranes 15, no. 12: 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120364

APA StyleSoni, I., Ahuja, M., Jagtap, P. K., Chauhan, V., Raj, S. K., & Sharma, P. P. (2025). The Advent of MXene-Based Synthetics and Modification Approaches for Advanced Applications in Wastewater Treatment. Membranes, 15(12), 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120364