Simple Analytical Approximations for Donnan Ion Partitioning in Permeable Ion-Exchange Membranes Under Reverse Electrodialysis Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

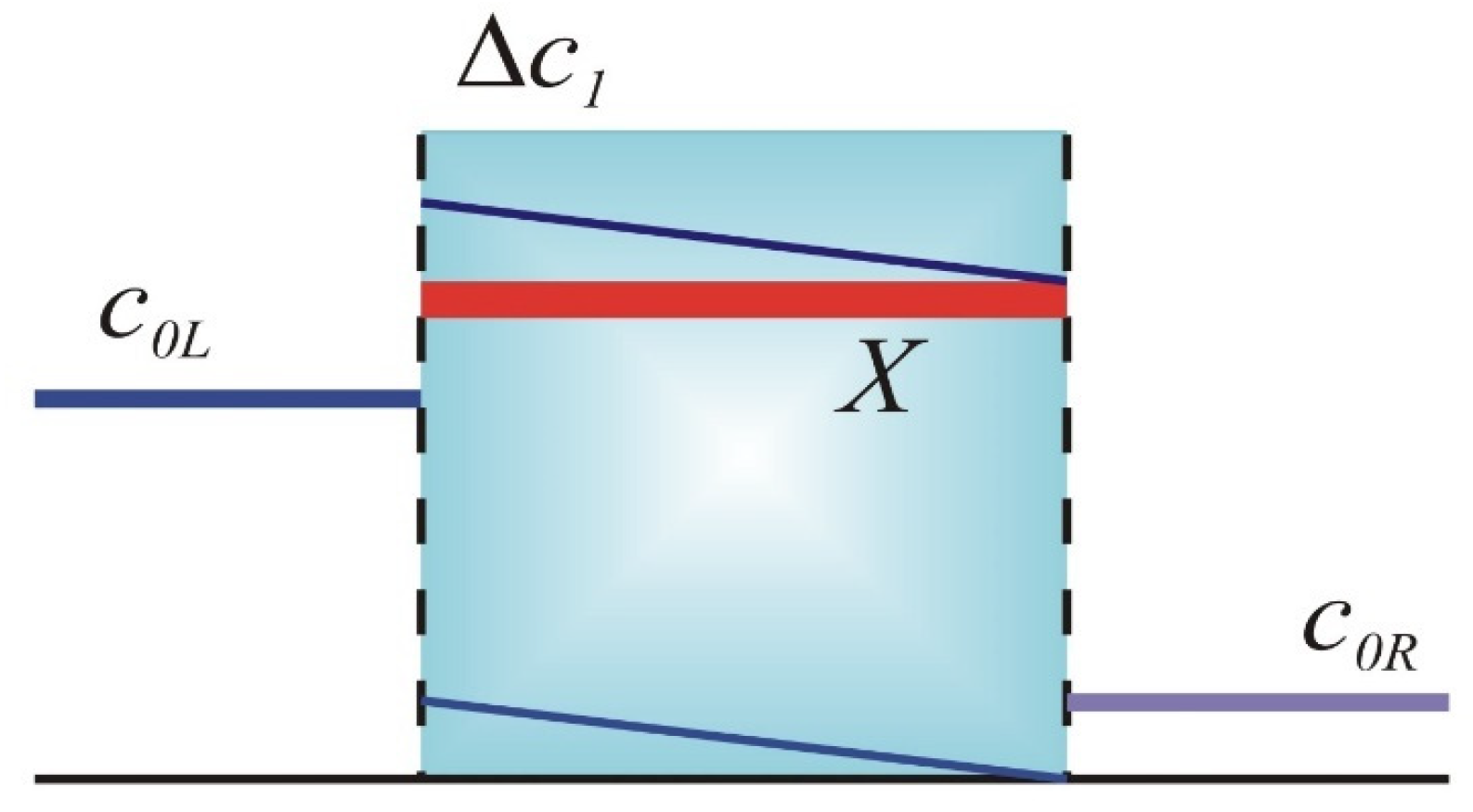

2. Ionic Partitioning in Permeable IEMs

3. Results and Discussion

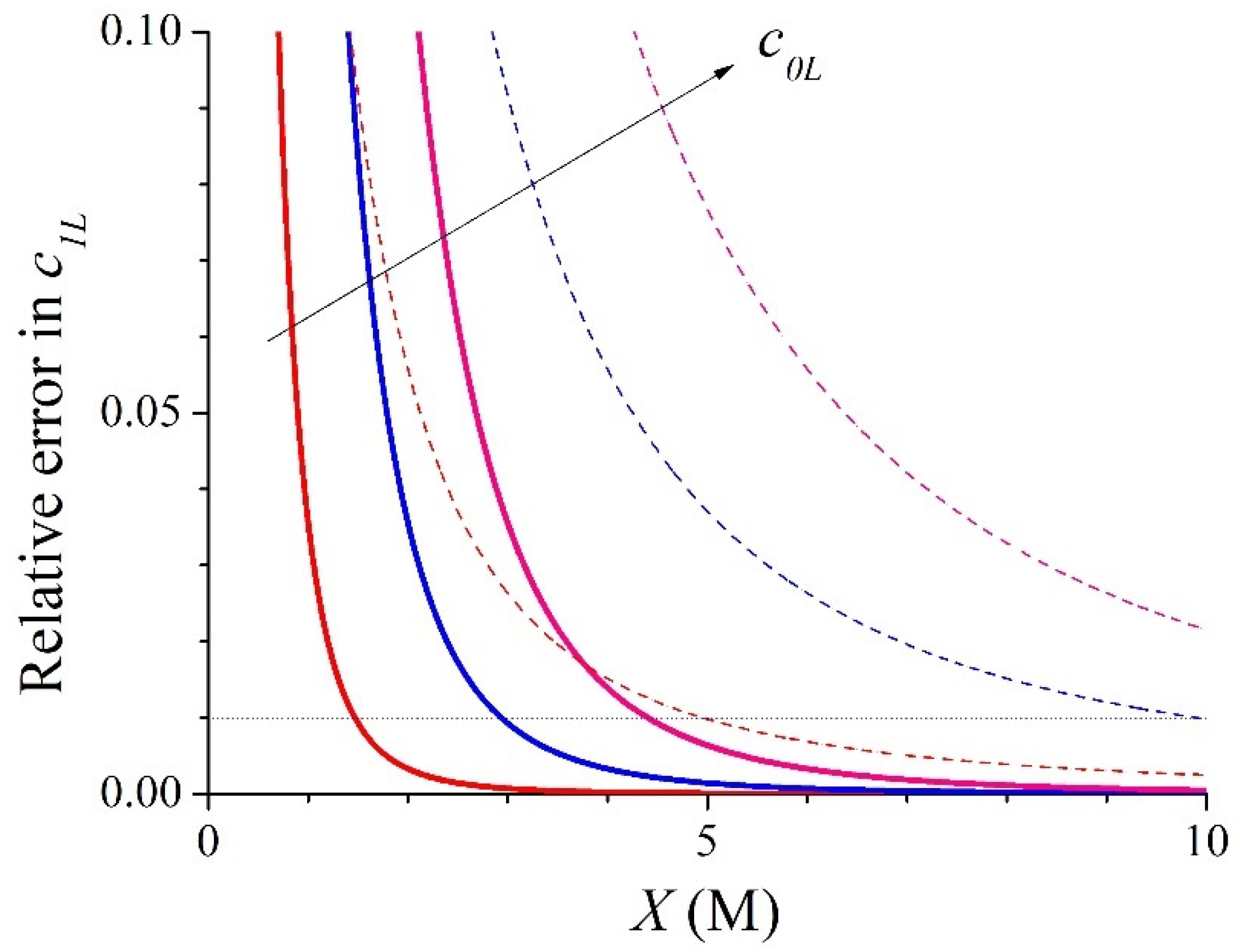

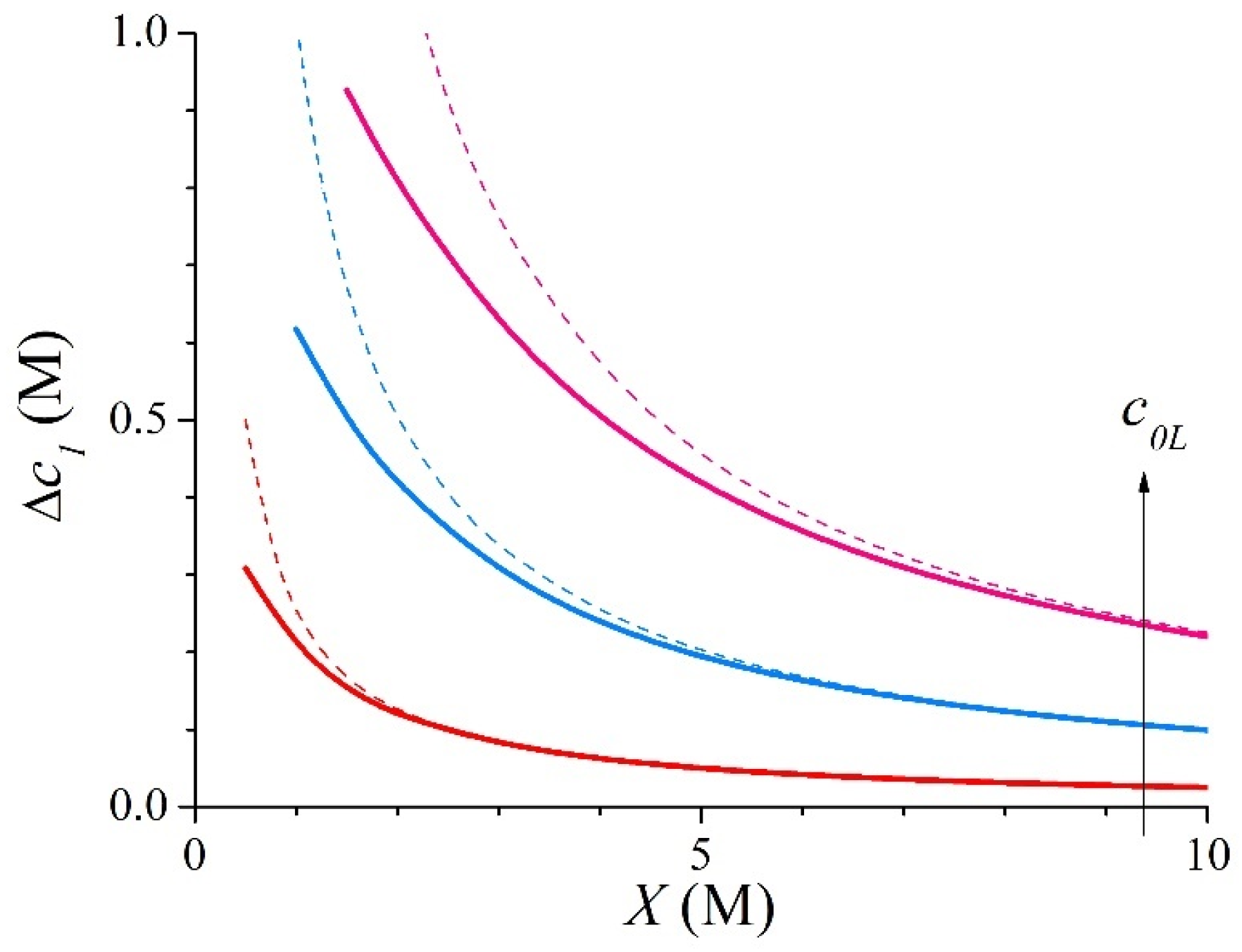

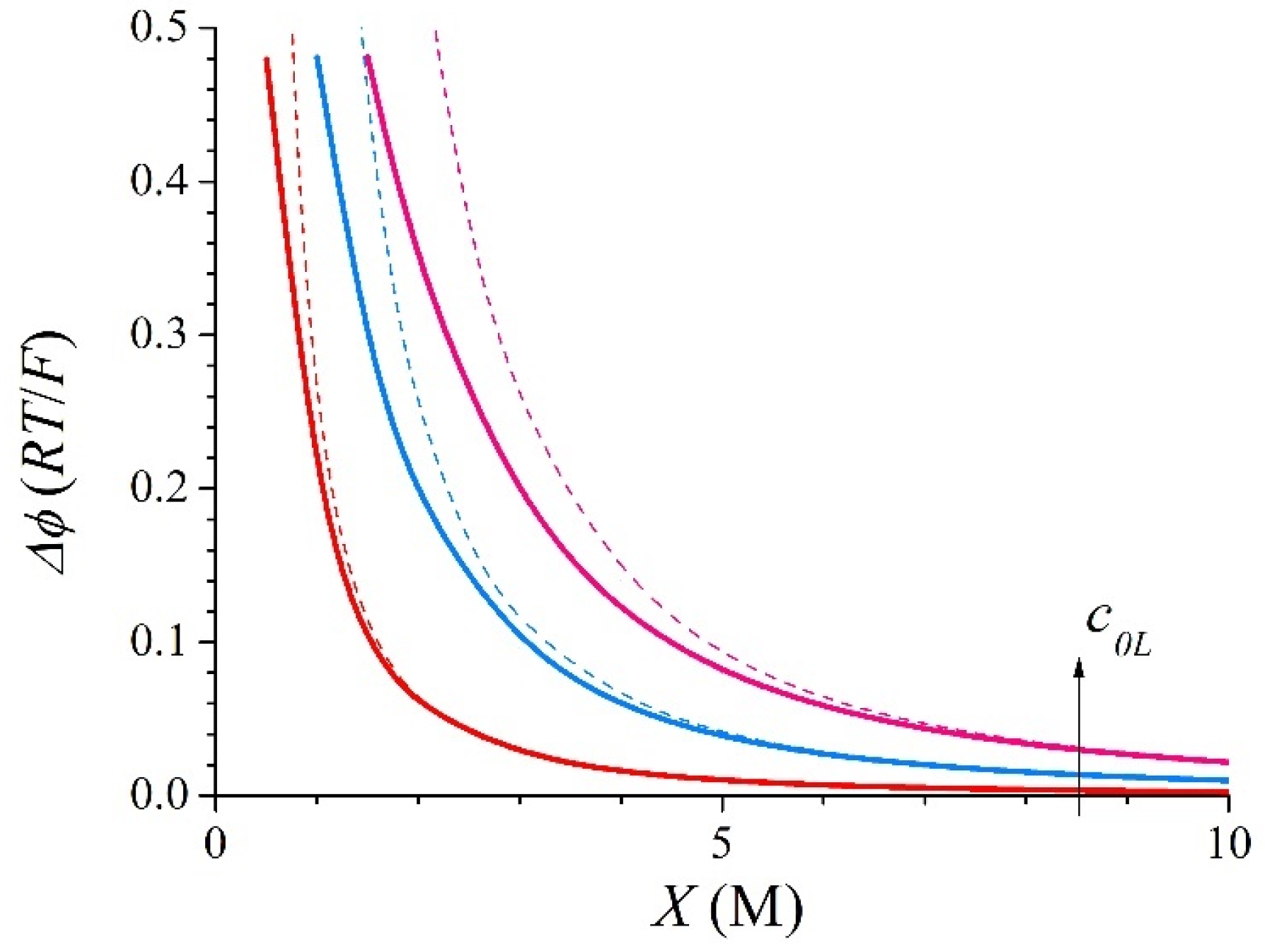

3.1. Symmetric Electrolyte

3.2. Asymmetric Electrolyte

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Generalised Expressions for a z1:z2 Electrolyte (z1c1K = −z2c2K = c0K)

| Total co-ion exclusion hypothesis | |

| Ion partitioning equations | |

| Expansions | |

| Counter-ion concentrations | |

| Counter-ion concentration gradient | |

| Variation in total Donnan electric potential | |

| Ionic partitioning coefficient | |

References

- Lee, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Coopera, N.J.; Elimelech, M. Directing the research agenda on water and energy technologies with process and economic analysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Elimelech, M. Salinity gradient energy is not a competitive source of renewable energy. Joule 2024, 8, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanoppen, M.; Criel, E.; Walpot, G.; Vermaas, D.A.; Verliefde, A. Assisted reverse electrodialysis—Principles; mechanisms; potential. Npj Clean Water 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, B.E.; Elimelech, M. Membrane-based processes for sustainable power generation using water. Nature 2012, 488, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.G.; Zhang, B.; Glabman, S.; Uzal, N.; Dou, X.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; Chen, Y. Potential ion exchange membranes and system performance in reverse electrodialysis for power generation: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 486, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufa, R.A.; Pawlowski, S.; Veerman, J.; Bouzeka, K.; Fontananova, E.; di Profio, G.; Velizarov, S.; Crespo, J.G.; Nijmeijer, K.; Curcio, E. Progress and prospects in reverse electrodialysis for salinity gradient energy conversion and storage. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 290–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Tang, C.Y. Recent developments and future perspectives of reverse electrodialysis technology: A review. Desalination 2018, 425, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, M.; Bandura, B. Renewable energy by reverse electrodialysis. Desalination 2007, 205, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.W.; Hamelers, H.V.M.; Buisman, C.J.N. Energy recovery from controlled mixing salt and fresh water with a reverse electrodialysis system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5785–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, J.; Saakes, M.; Nijmeijer, K.; Harmsen, G.J. Reverse electrodialysis: Performance of a stack with 50 cells on the mixing of sea and river water. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 327, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugolecki, P.; Gambier, A.; Nijmeijer, K.; Wessling, M. Practical potential of reverse electrodialysis as process for sustainable energy generation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 6888–6894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermass, D.A.; Bajracharya, S.; Sales, B.B.; Saakes, M.; Hamelers, B.; Nijmeijer, K. Clean energy generation using capacitive electrodes in reverse electrodialysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, D.-K. Energy harvesting from salinity gradient by reverse electrodialysis with anodic alumina nanopores. Energy 2013, 51, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, M.; Brauns, E.; Cipollina, A.; Micale, G.; Modica, P.; Russo, G.; Helsen, J. Reverse electrodialysis with saline waters and concentrated brines: A laboratory investigation towards technology scale-up. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 492, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.-K. Membrane electrode assembly for energy harvesting from salinity gradient by reverse electrodialysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 550, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Coma, L.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Carmona, J.; Palacio, L.; Prádanos, P.; Fallanza, M.; Ortiz, A.; Ibañez, R.; Ortiz, I. Modeling the influence of divalent ions on membrane resistance and electric power in reverse electrodialysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 592, 117385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfferich, F. Ion Exchange; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco, M.; Hamelers, H.V.M.; Biesheuvel, P.M. Nernst-Planck transport theory for (reverse) electrodialysis: I. Effect of co-ion transport through the membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 510, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.A. A numerical comparison of optimal load and internal resistances in ion-exchange membrane systems under reverse electrodialysis conditions. Desalination 2016, 392, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.A. Numerical simulation of ionic transport processes through bilayer ion-exchange membranes in reverse electrodialysis stacks. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 524, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurreri, L.; Battaglia, C.; Tamburini, A.; Cipollina, A.; Micalle, G.; Ciofalo, M. Multi-physical modelling of reverse electrodialysis. Desalination 2017, 423, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.A. A Nernst-Planck analysis on the contributions of the ionic transport in permeable ion-exchange membranes to the open circuit voltage and the membrane resistance in reverse electrodialysis stacks. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 238, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Huang, J.; Tan, X.; Zeng, J.; Liu, X.; Tao, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. Development of binary-salt working solutions for improving the performance of reverse electrodialysis. Desalination 2025, 614, 119176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontturi, K.; Murtomäki, L.; Manzanares, J.A. Ionic Transport Processes; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gokturk, P.A.; Sujanani, R.; Qian, J.; Wang, Y.; Katz, L.E.; Freeman, B.D.; Crumlin, E.J. The Donnan potential revealed. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.A. Uphill transport in improved reverse electrodialysis by removal of divalent cations in the dilute solution: A Nernst-Planck based study. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 598, 117784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdadi, A.; Greenlee, L.F.; Logan, B. Uphill transport of sulfate and chloride ions under different operational conditions of a reverse electrodialysis (RED) stack. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 508, 160897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, D.; Wang, X.; Wessling, M. Combining Manning’s theory and the ionic conductivity experimental approach to characterize selectivity of cation exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 629, 119263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Duddu, R.; Lin, S. Extended Donnan-Manning theory for selective ion partition and transport in ion exchange membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2023, 681, 121782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elozeiri, A.A.E.; Dykstra, J.E.; Rijnaarts, H.H.M.; Lammertink, R.G.H. Multi-component ion equilibria and transport in ion-exchange membranes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 673, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpura, G.; Papiewska, E.; Culcasi, A.; Filingeri, A.; Tamburini, A.; Ferrari, M.C.; Micale, G.; Cipollina, A. Modelling of selective ion partitioning between ion-exchange membranes and highly concentrated multi-ionic brines. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 700, 122659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Biesheuvel, P.M.; Elimelech, M. Extended Donnan model for ion partitioning in charged nanopores: Application to ion-exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 705, 122921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.J.; Kho, M.; Che, X.; Goh, K.B. Selective divalent/monovalent ion partitioning in cation exchange membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 356, 129833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleón, J.A.; Moya, A.A. Network simulation of the electrical response of ion-exchange membranes with fixed charge varying linearly with position. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2008, 613, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleón, J.A.; Moya, A.A. Transient electrical response of ion-exchange membranes with fixed-charge due to ion adsorption. A network simulation approach. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2009, 633, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamcev, J.; Galizia, M.; Benedetti, F.M.; Jang, E.-.S.; Paul, D.R.; Freeman, B.D.; Manning, G.S. Partitioning of mobile ions between ion exchange polymers and aqueous salt solutions: Importance of counter-ion condensation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 6021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, A.; Valdés, H.; Velásquez, J.; Hernández, S. Comparative analysis of Donnan steric partitioning pore model and dielectric exclusion applied to the fractionation of aquous saline solutions through nanofiltration. Chemengineering 2024, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Y. Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation; reverse electrodialysis, and everything in between. Phys. Rev. E 2025, 111, 064408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerman, J.; Gómez-Coma, L.; Ortiz, A.; Ortiz, I. Resistance of ion exchange membranes in aqueous mixtures of monovalent and divalent ions and the effect on reverse electrodialysis. Membranes 2023, 13, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galama, A.H.; Post, J.W.; Stuart, M.A.C.; Biesheuvel, P.M. Validity of the Boltzmann equation to describe Donnan equilibrium at the membrane–solution interface. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 442, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauns, E. Salinity gradient power by reverse electrodialysis: Effect of model parameters on electrical power output. Desalination 2009, 237, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; He, W.; Logan, B.E. Reducing pumping energy by using different flow rates of high and low concentration solutions in reverse electrodialysis cells. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 486, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Abdu, S.; Wessling, M. Selectivity of ion exchange membranes: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 555, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.wolfram.com/mathematica (accessed on 1 November 2025).

| X (M) | c1L (M) | c1R (M) | ∆c1 (M) | ∆ϕ (RT/F) | kL | kR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | X | ||||||

| 1 | Ex. | 1.207 | 1.000 | 0.207 | 0.180 | 2.414 | 50.02 |

| Ap. | 1.250 | 1.000 | 0.250 | 0.250 | 2.500 | 50.00 | |

| % Err. | 3.6 | <0.1 | 20.9 | 33.1 | 3.6 | <0.1 | |

| 3 | Ex. | 3.081 | 3.000 | 0.081 | 0.027 | 6.162 | 150.01 |

| Ap. | 3.083 | 3.000 | 0.083 | 0.028 | 6.167 | 150.00 | |

| % Err. | <0.1 | <0.1 | 2.9 | 4.3 | <0.1 | <0.1 | |

| 5 | Ex. | 5.050 | 5.000 | 0.049 | 0.010 | 10.10 | 250.00 |

| Ap. | 5.050 | 5.000 | 0.050 | 0.010 | 10.10 | 250.00 | |

| % Err. | <0.1 | <0.1 | 1.2 | 1.6 | <0.1 | <0.1 | |

| X (M) | c1L (M) | c1R (M) | ∆c1 (M) | ∆ϕ (RT/F) | kL | kR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | |||||||

| 1 | Ex. | 0.655 | 0.500 | 0.153 | 0.133 | 1.618 | 7.081 |

| Ap. | 0.677 | 0.500 | 0.177 | 0.177 | 1.645 | 7.071 | |

| % Err. | 3.4 | <0.1 | 15.5 | 31.7 | 1.7 | <0.1 | |

| 3 | Ex. | 1.599 | 1.501 | 0.098 | 0.032 | 2.529 | 12.25 |

| Ap. | 1.602 | 1.500 | 0.102 | 0.034 | 2.531 | 12.25 | |

| % Err. | <0.1 | <0.1 | 4.1 | 7.5 | <0.1 | <0.1 | |

| 5 | Ex. | 2.578 | 2.501 | 0.078 | 0.015 | 3.211 | 15.81 |

| Ap. | 2.579 | 2.500 | 0.079 | 0.016 | 3.219 | 15.81 | |

| % Err. | <0.1 | <0.1 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 0.2 | <0.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moya, A.Á. Simple Analytical Approximations for Donnan Ion Partitioning in Permeable Ion-Exchange Membranes Under Reverse Electrodialysis Conditions. Membranes 2025, 15, 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120365

Moya AÁ. Simple Analytical Approximations for Donnan Ion Partitioning in Permeable Ion-Exchange Membranes Under Reverse Electrodialysis Conditions. Membranes. 2025; 15(12):365. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120365

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoya, Antonio Ángel. 2025. "Simple Analytical Approximations for Donnan Ion Partitioning in Permeable Ion-Exchange Membranes Under Reverse Electrodialysis Conditions" Membranes 15, no. 12: 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120365

APA StyleMoya, A. Á. (2025). Simple Analytical Approximations for Donnan Ion Partitioning in Permeable Ion-Exchange Membranes Under Reverse Electrodialysis Conditions. Membranes, 15(12), 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120365