Ion Exchange Membrane-like Deposited Electrodes for Capacitive De-Ionization: Performance Evaluation and Mechanism Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Electrode Preparation

2.3. Characterization

2.4. System Setup and Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Electrode and AEM

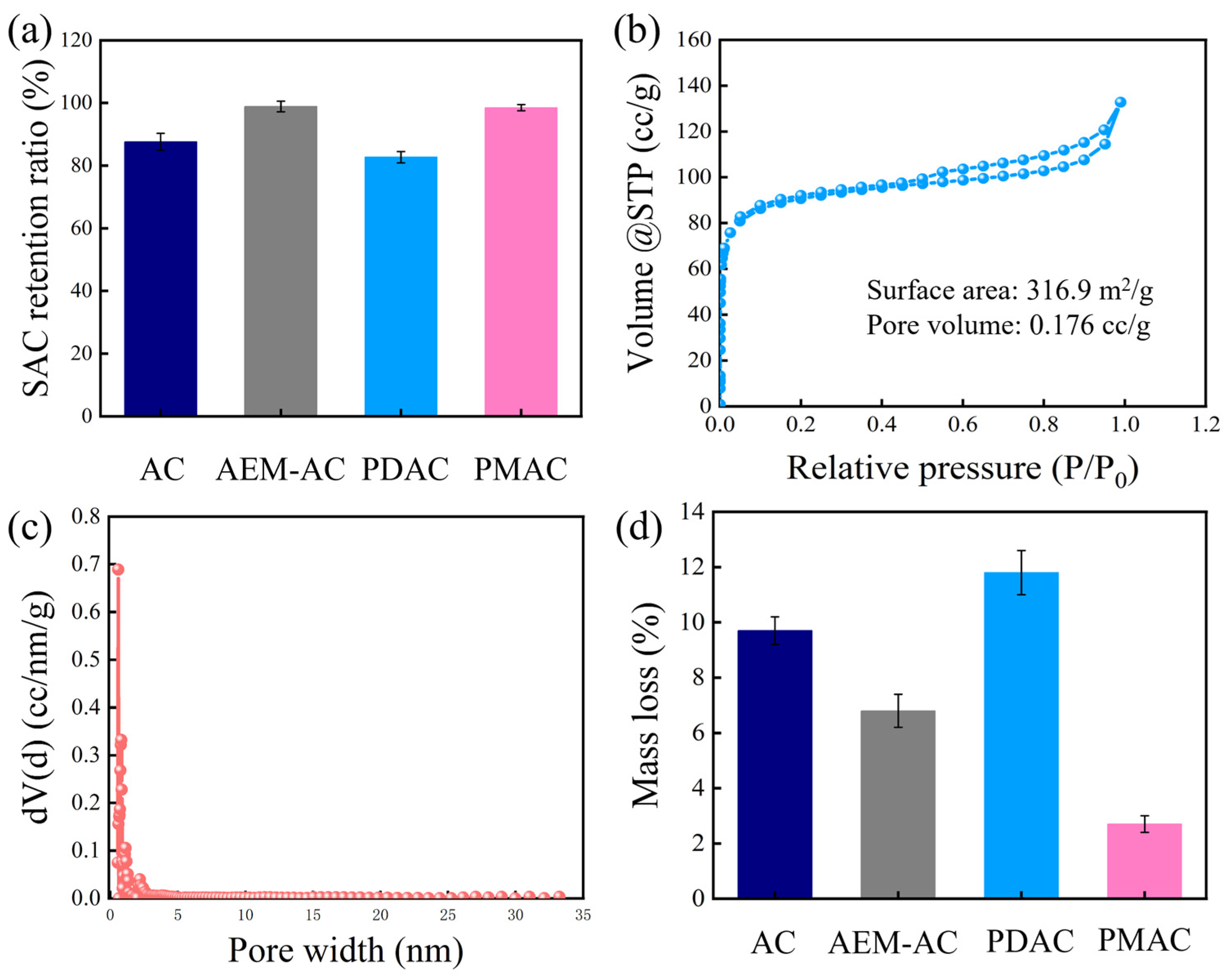

3.2. Performance Evaluation of Different Electrodes

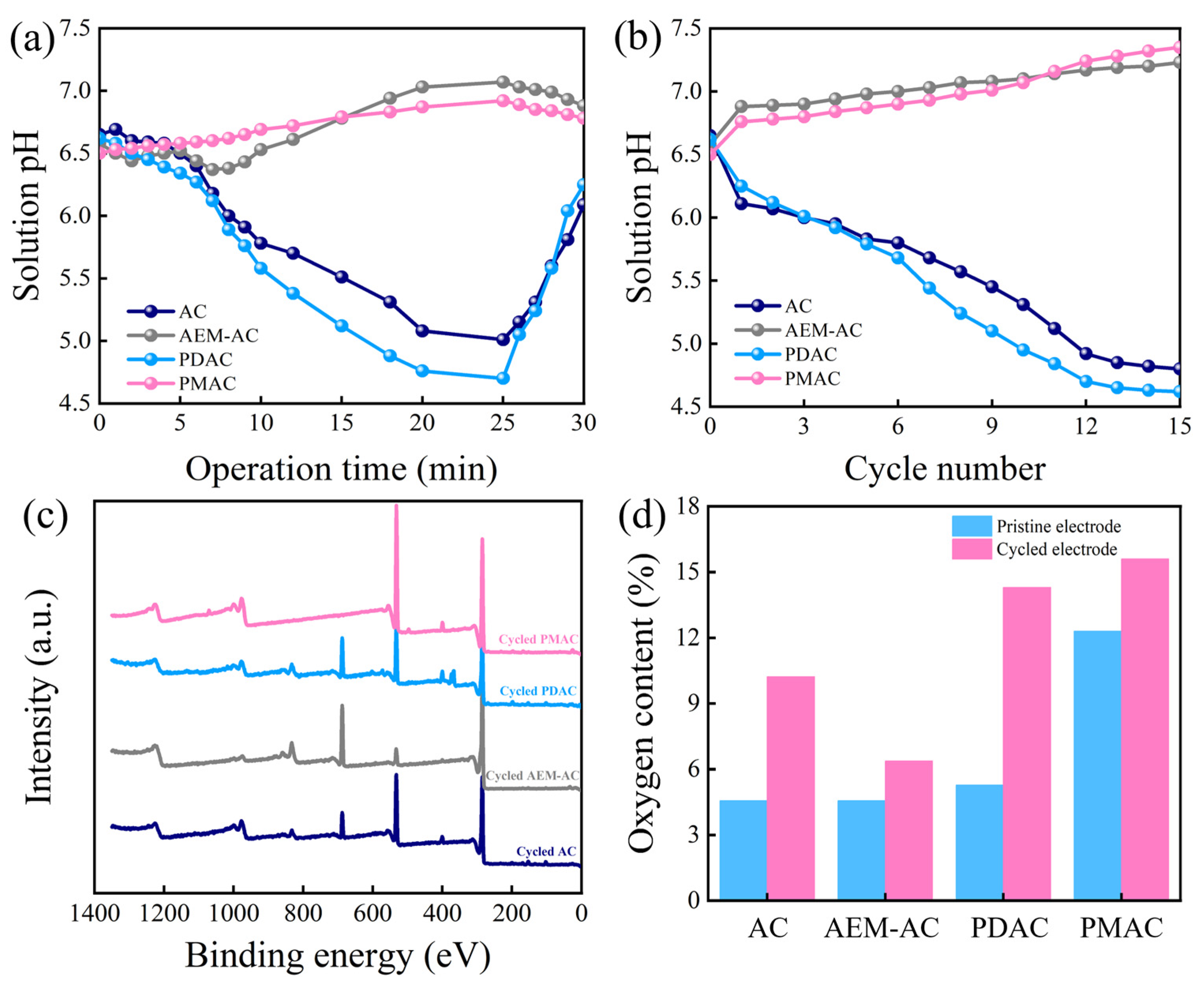

3.3. Mechanism Investigation

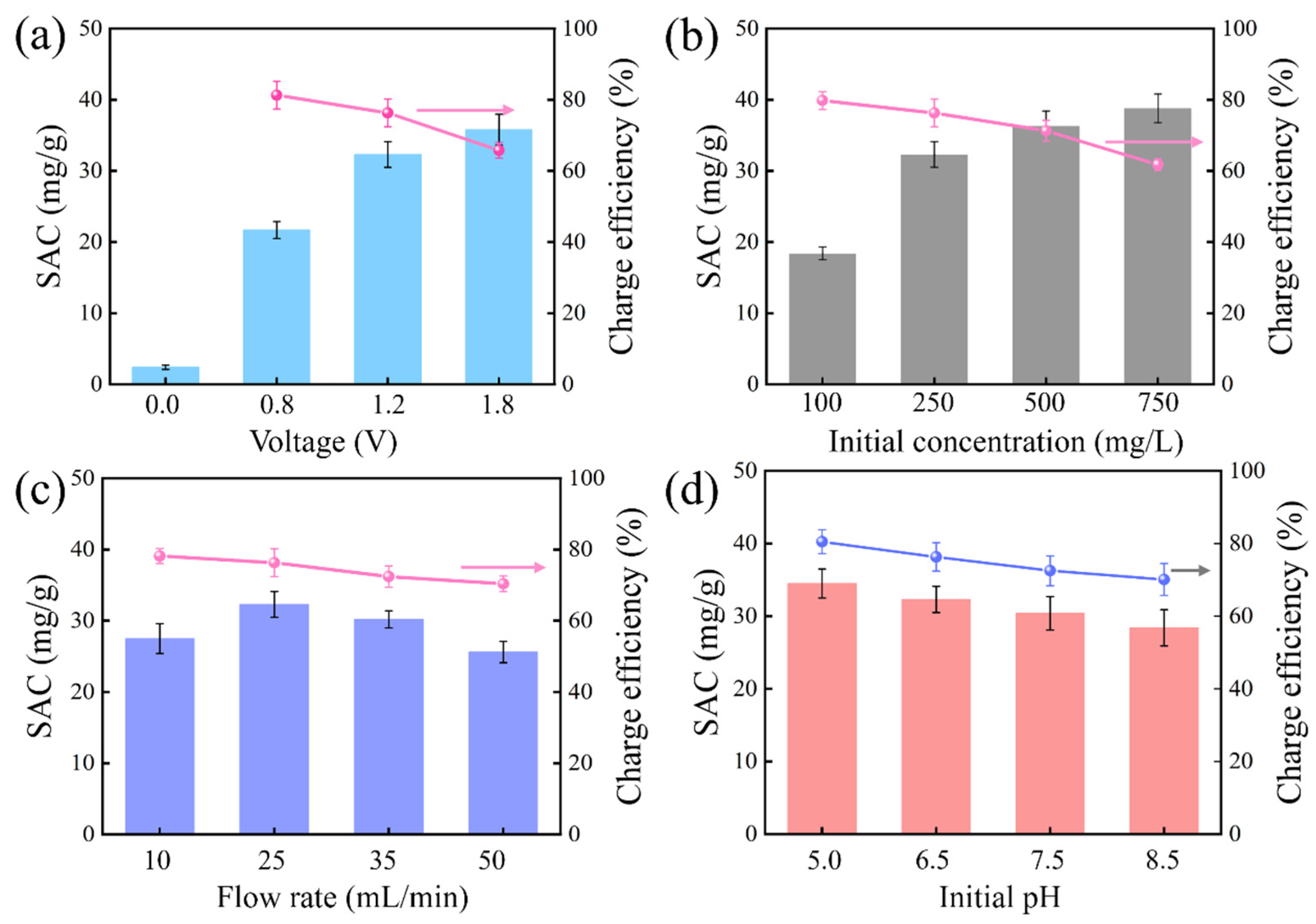

3.4. Effect of Operation Parameters on PMAC Performance

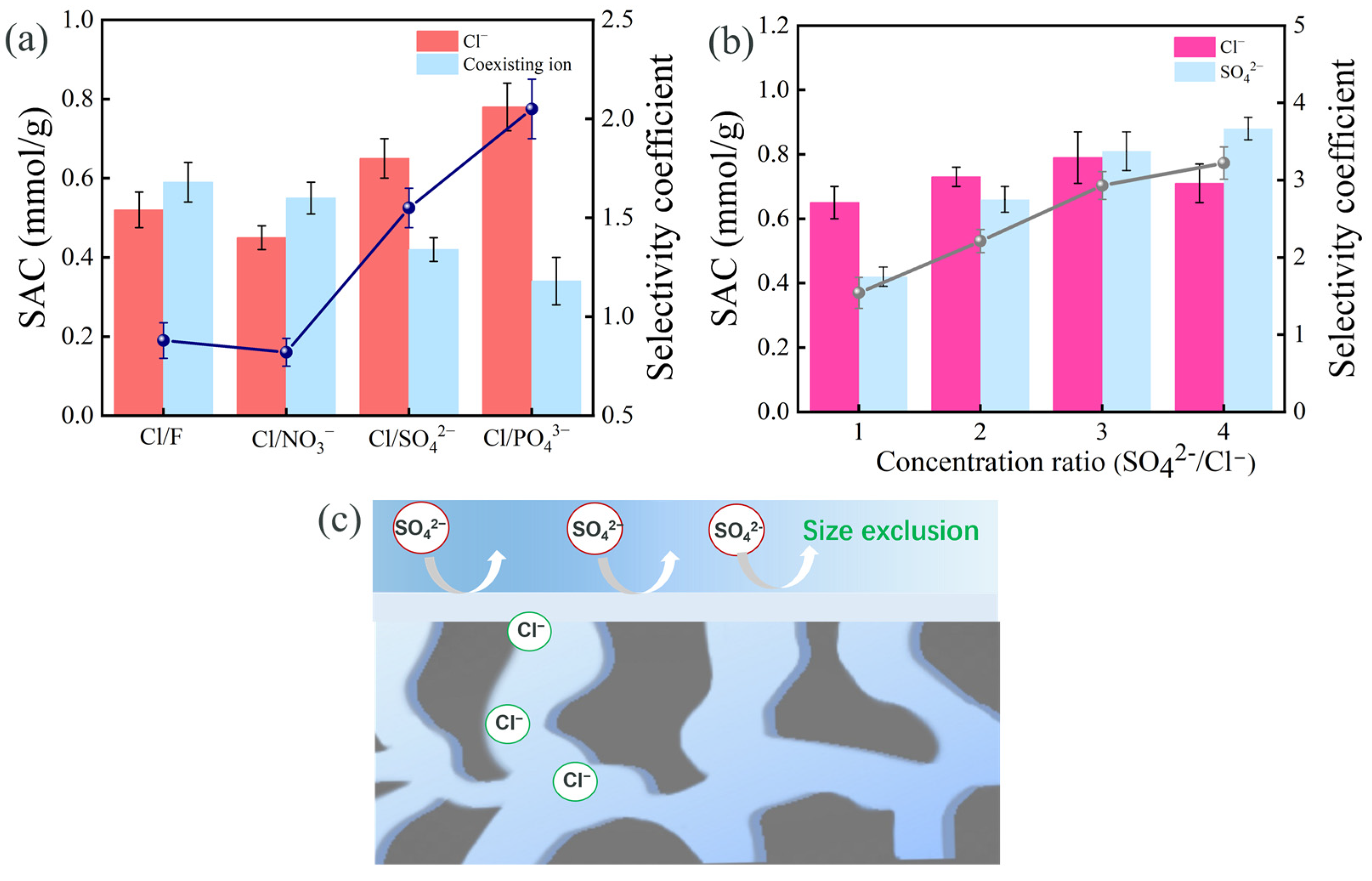

3.5. Monovalent Ion Selectivity of PMAC

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Activated carbon | AC |

| Glutaraldehyde | GA |

| Polyethyleneimine | PEI |

| PEI-doped activated carbon | PDAC |

| PEI-based membrane activated carbon | PMAC |

| Anion exchange membrane | AEM |

| Salt adsorption capacity | SAC |

| Capacitive de-ionization | CDI |

| Water contact angle | WCA |

References

- Chaudhry, F.N.; Malik, M.F. Factors Affecting Water Pollution: A Review. J. Ecosyst. Ecogr. 2017, 7, 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Pei, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shu, L.; Zhang, H. Twenty Years of China’s Water Pollution Control: Experiences and Challenges. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yang, H.; Xu, X. Effects of Water Pollution on Human Health and Disease Heterogeneity: A Review. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 880246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.N.; Jin, B.; Chow, C.W.; Saint, C. Recent Developments in Photocatalytic Water Treatment Technology: A Review. Water Res. 2010, 44, 2997–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Kansha, Y. Comprehensive Review of Industrial Wastewater Treatment Techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 51064–51097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, J.E.; Zhao, R.; Biesheuvel, P.M.; Van der Wal, A. Resistance Identification and Rational Process Design in Capacitive Deionization. Water Res. 2016, 88, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Aldaqqa, N.M.; Alhseinat, E.; Shetty, D. Electrode Materials for Desalination of Water via Capacitive Deionization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202302180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, R.; Wu, M.; Shi, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, W. Faradaic Rectification in Electrochemical Deionization and Its Influence on Cyclic Stability. ACS ES&T Eng. 2024, 4, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suss, M.E.; Porada, S.; Sun, X.; Biesheuvel, P.M.; Yoon, J.; Presser, V. Water desalination via capacitive deionization: What is it and what can we expect from it? Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2296–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, R.; Yu, F. Hotspots and Future Trends of Capacitive Deionization Technology: A Bibliometric Review. Desalination 2024, 571, 117107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Xin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Ding, W.; Luo, Y. Application of Capacitive Deionization in Water Treatment and Energy Recovery: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, X.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Lu, T.; Pan, L. Design of three-dimensional faradic electrode materials for high-performance capacitive deionization. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 510, 215835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-B.; Park, K.-K.; Eum, H.-M.; Lee, C.-W. Desalination of a thermal power plant wastewater by membrane capacitive deionization. Desalination 2006, 196, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; He, D.; Tang, W.; Kovalsky, P.; Waite, T.D. Investigation of pH-dependent phosphate removal from wastewaters by membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI). Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2017, 3, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, P.A.; Zisopoulos, F.; Verheggen, S.; Schroën, K.; Boom, R. Exergy analysis of membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI). Desalination 2018, 444, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Miller, C.J.; Fletcher, J.; Lian, B.; Waite, T.D. Insufficient desorption of ions in constant-current membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI): Problems and solutions. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Guo, H.; Zhang, W.; Xu, K.; Li, B. Mass transfer in hollow fiber vacuum membrane distillation process based on membrane structure. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 532, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Miller, C.J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fletcher, J.; Waite, T.D. Membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI): A flexible and tunable technology for customized water softening. Water Res. 2024, 259, 121871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Choi, J.-H. Fabrication and characterization of a carbon electrode coated with cation-exchange polymer for the membrane capacitive deionization applications. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 355, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, R.; Szekely, G.; Dryfe, R.A.W. Sustainable processing of electrodes for membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI). J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 342, 130922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Omosebi, A.; Holubowitch, N.; Liu, A.; Ruh, K.; Landon, J.; Liu, K. Polymer-coated composite anodes for efficient and stable capacitive deionization. Desalination 2016, 399, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, R.; Szekely, G.; Dryfe, R.A.W. Ion-Exchange Materials for Membrane Capacitive Deionization. ACS ES&T Water 2020, 1, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ren, L.-F.; Ying, D.; Jia, J.; Shao, J. Enhancing performance of capacitive deionization under high voltage by suppressing anode oxidation using a novel membrane coating electrode. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 652, 120506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.-T.; Young, T.-H. Polyetherimide membrane formation by the cononsolvent system and its biocompatibility of MG63 cell line. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 269, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H. Ultrahigh Dielectric Energy Density and Efficiency in PEI-Based Gradient Layered Polymer Nanocomposite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2406148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Chen, X.; Cai, T.; Tong, X.; Wang, Z. Surface energy-induced anti-wetting and anti-fouling enhancement of Janus membrane for membrane distillation. Water Res. 2024, 263, 122176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Araji, D.D.; Al-Ani, F.H.; Alsalhy, Q.F. Polyethyleneimine (PEI) grafted silica nanoparticles for polyethersulfone membranes modification and their outlooks for wastewater treatment—A review. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021, 103, 4752–4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Pan, L.; Xu, X.; Lu, T.; Sun, Z.; Chua, D.H. Enhanced desalination efficiency in modified membrane capacitive deionization by introducing ion-exchange polymers in carbon nanotubes electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 130, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Gao, T.; Gong, A.; Liang, P. Sustained Phosphorus Removal and Enrichment through Off-Flow Desorption in a Reservoir of Membrane Capacitive Deionization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3031–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNair, R.; Cseri, L.; Szekely, G.; Dryfe, R.A. Asymmetric Membrane Capacitive Deionization Using Anion-Exchange Membranes Based on Quaternized Polymer Blends. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 2946–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-R.; Kim, K.-M.; Kim, J.-G. Organic corrosion inhibitor without discharge retardation of aluminum-air batteries. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 365, 120104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bales, C.; Lian, B.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Fletcher, J.; Waite, T.D. Photovoltaic powered operational scale Membrane Capacitive Deionization (MCDI) desalination with energy recovery for treated domestic wastewater reuse. Desalination 2023, 559, 116647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, F.; Huang, L.; Sun, H.; Guo, X. Polyhydroxy phenolic resin coated polyetherimide membrane with biomimetic super-hydrophily for high-efficient oil–water separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamaethiralalage, J.G.; Singh, K.; Sahin, S.; Yoon, J.; Elimelech, M.; Suss, M.E.; Liang, P.; Biesheuvel, P.M.; Zornitta, R.L.; de Smet, L.C.P.M. Recent advances in ion selectivity with capacitive deionization. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 1095–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-W.; Hackl, L.; Kumar, A.; Hou, C.-H. Exploring the electrosorption selectivity of nitrate over chloride in capacitive deionization (CDI) and membrane capacitive deionization (MCDI). Desalination 2021, 497, 114764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Peng, J.; Yang, S.; Jin, R.; Liu, C.; Huang, Q. Synthesis of Low-Crystalline MnO2/MXene Composites for Capacitive Deionization with Efficient Desalination Capacity. Metals 2023, 13, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cui, J.; Feng, A.; Liu, K.; Yu, Y. Enhanced Capacitive Deionization Performance of Ti3C2T x/C via Structural Modification Assisted by PMMA-Derived Carbon Spheres. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 5470–5479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ning, X.A.; Huang, Y.; Li, S. Nitrogen-Rich Microporous Carbon Materials for High-Performance Membrane Capacitive Deionization. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 312, 251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.H.; ul Haq, O.; Choi, J.H.; Lee, Y.S. Sulfonated Poly (Ether Ether Ketone) Ion-Exchange Membrane for Membrane Capacitive Deionization Applications. Macromol. Res. 2018, 26, 1273–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Mishra, S.; Upadhyay, P.; Kulshrestha, V. Carbon-Based Electrode Materials with Ion Exchange Membranes for Enhanced Membrane Capacitive Deionization. Colloids Surf. A 2023, 676, 132064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Ding, Z.; Meng, F.; Lu, T.; Pan, L. Ultra-Durable and Highly-Efficient Hybrid Capacitive Deionization by MXene Confined MoS2 Heterostructure. Desalination 2022, 528, 115616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.W.; Choi, J.H. Suppression of Electrode Reactions and Enhancement of the Desalination Performance of Capacitive Deionization Using a Composite Carbon Electrode Coated with an Ion-Exchange Polymer. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 278, 119503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrode | C (%) | N (%) | O (%) | F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | 81.7 | 0.9 | 4.6 | 12.8 |

| PDAC | 69.8 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 20.5 |

| PMAC | 65.4 | 7.5 | 24.4 | 2.7 |

| Electrode | C (%) | N (%) | O (%) | F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycled AC | 74.6 | 0.7 | 14.4 | 10.3 |

| Cycled AEM-AC | 74.3 | 0.4 | 6.5 | 18.8 |

| Cycled PDAC | 69.3 | 4.4 | 17.7 | 8.6 |

| Cycled PMAC | 67.1 | 4.3 | 27.2 | 1.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, S.; Wang, C.; Leng, T.; Zhang, C.; Ren, L.-F.; Shao, J. Ion Exchange Membrane-like Deposited Electrodes for Capacitive De-Ionization: Performance Evaluation and Mechanism Study. Membranes 2025, 15, 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110338

Xue S, Wang C, Leng T, Zhang C, Ren L-F, Shao J. Ion Exchange Membrane-like Deposited Electrodes for Capacitive De-Ionization: Performance Evaluation and Mechanism Study. Membranes. 2025; 15(11):338. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110338

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Siyue, Chengyi Wang, Tianxiao Leng, Chenglin Zhang, Long-Fei Ren, and Jiahui Shao. 2025. "Ion Exchange Membrane-like Deposited Electrodes for Capacitive De-Ionization: Performance Evaluation and Mechanism Study" Membranes 15, no. 11: 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110338

APA StyleXue, S., Wang, C., Leng, T., Zhang, C., Ren, L.-F., & Shao, J. (2025). Ion Exchange Membrane-like Deposited Electrodes for Capacitive De-Ionization: Performance Evaluation and Mechanism Study. Membranes, 15(11), 338. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110338