High Current Induction for the Effective Bending in Ionic Polymer Metal Composite

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Artificial muscle: IPMC represents a class of artificial muscles. One of the authors of this paper, Tamagawa, along with his former colleagues, fabricated an IPMC using a silver-coated Selemion CMV, where Selemion CMV is a cation exchange membrane manufactured by Asahi Glass Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). This IPMC exhibits significant bending in response even to quite low-voltage stimulation. During actuation, the silver layer on the membrane surface undergoes a redox reaction, represented by the equation: 4Ag + O2 ⇌ 2Ag2O. Concurrently, a notable increase in current is observed [22,23]. These findings suggest that effective bending is strongly linked to the silver redox reaction and the associated increase in current flow, indicating that oxygen plays a critical role in the actuation behavior of IPMCs.

- Biological muscle: The Murburn concept is a novel biological hypothesis proposed by K. M. Manoj in the 2010s [30,31,32,33]. Traditionally, reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been considered harmful byproducts of metabolism. However, according to the Murburn concept, ROS functions as essential mediators in electron transfer processes. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that the activation of biological muscles involves oxygen and ROS more integrally than ordinarily believed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Preparation

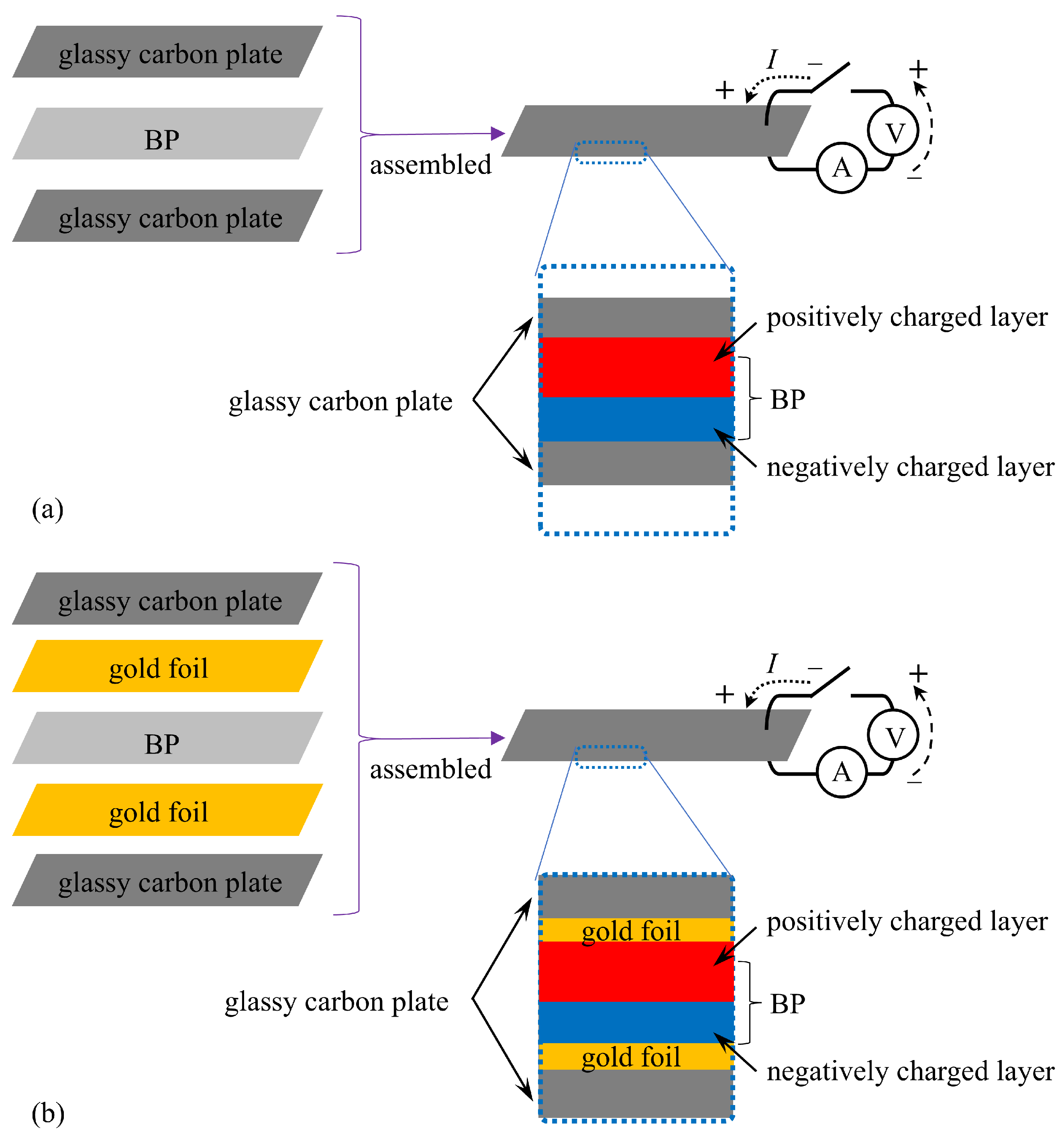

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Bending Curvature Measurement

2.2.2. Current Measurement

2.3. Environmental Conditions in the Lab

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Characteritics of BP-IPMC

3.2. Current of BPs

3.2.1. Doping

3.2.2. Oxygen Supply

- t = 0 ∼ 60 s BP-IPMC is exposed to the N2 supply

- t = 60 ∼ 120 s BP-IPMC is in the air without the supply of O2 or N2.

- t = 120 ∼ 180 s BP-IPMC is exposed to the O2 supply

- t = 180 ∼ 240 s BP-IPMC is exposed to the N2 supply

- t = 240 ∼ 300 s BP-IPMC is in the air without the supply of O2 or N2.

- t = 300 ∼ 360 s BP-IPMC is exposed to the O2 supply

3.3. Doping and the Use of Oxygen for Effective Bending

- (i)

- Electrical tight contact between the surace of Neosepta and the electrode

- (ii)

- Doping with AgNO3

- (iii)

- Oxygen supply

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Detail of the Experimental Setup Illustrated in Figure 2

Appendix B. Stability of Bending of BP-IPMC in the Dry and Wet State

References

- Bar-Cohen, Y.; Xue, T.; Joffe, B.; Lih, S.-S.; Shahinpoor, M.; Simpson, J.; Smith, J.; Willis, P. Electroactive polymers (EAP) low mass muscle actuators. In Proceedings of the SPIE Conference on Smart Material Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–6 March 1997; Volume 3041, pp. 697–701. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Cohen, Y.; Xue, T.; Shahinpoor, M.; Simpson, J.O.; Smith, J. Low-mass muscle actuators using electroactive polymers (EAP). In Proceedings of the SPIE Conference on Smart Material Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 1–5 March 1998; Volume 3324, pp. 218–223. [Google Scholar]

- Osada, Y. (Ed.) Handbook on Biomimetics; NTS Inc.: Yokohama, Japan, 2000. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Hara, S.; Zama, T.; Takashima, W.; Kaneto, K. Artificial Muscles Based on Polypyrrole Actuators with Large Strain and Stress Induced Electrically. Polym. J. 2004, 36, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.S.; Peteu, S.F.; Ly, J.V.; Requicha, A.A.G.; Thompson, M.E.; Zhou, C. Actuation of polyptrrole nanowires. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 165501. [Google Scholar]

- Petralia, M.T.; Wood, R.J. Fabrication and analysis of dielectric-elastomer minimum-energy structures for highly-deformable soft robotic systems. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 2357–2363. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, R.; Keplinger, C.; Kaltseis, R.; Schwodiauer, R.; Bauer, S. Dielectric elastomers: From the beginning of modern science to applications in actuators and energy harvesters. Electroact. Polym. Actuators Devices (EAPAD) 2011, 7976, 797603. [Google Scholar]

- Katchalsky, A. Rapid swelling and deswelling of reversible gels of polymeric acids by ionization. Expeirmentia 1949, 5, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, W.; Hargitay, B.; Katchalsky, A.; Eisenberg, H. Reversible Dilation and Contraction by Changing the State of Ionization of High-Polymer Acid Networks. Nature 1950, 165, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackel, M. (Ed.) Humanoid Robots: Human-Like Machines; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T. Classification and Research Trend of Soft Actuators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T. Gels. Sci. Am. 1982, 244, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguro, K.; Kawami, Y.; Takenaka, H. Bending of anion-Conducting Polymer Film-Electrode Composite by an Electric Stimulus at Low Voltage. J. Micromach. Soc. 1992, 5, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Salehpoor, K.; Shahinpoor, M.; Mojarrad, M. Linear and Platform Type Robotic Actuators Made From Ion-Exchange Membrane-Metal Composites. Proc. Spie Conf. Smart Mater. Technol. 1997, 3040, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Shahinpoor, M.; Bar-Cohen, Y.; Xue, T.; Simpson, J.O.; Smith, J.; Hung, M.; Sheng, M. Some Experimental Results on Ionic Polymer-Metal Composites (IPMC) As Biomimetic Sensors and Actuator. Proc. Spie Conf. Smart Mater. Technol. 1998, 3324, 251–267. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B.-K.; Ju, M.-S.; Lin, C.-C.K. A new approach to develop ionic polymer–metal composites (IPMC) actuator: Fabrication and control for active catheter systems. Sens. Actuators A 2007, 137, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Palmre, V.; Hwang, T.; Kim, K.; Yim, W.; Bae, C. Electromechanical performance and other characteristics of IPMCs fabricated with various commercially available ion exchange membranes. Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23, 074001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaari, M.F.; Saw, S.K.; Samad, Z. Fabrication and Characterization of IPMC Actuator for Underwater Micro Robot Propulsor. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 575, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annabestani, M.; Naghavi, N.; Maymandi-Nejad, M. A 3D analytical ion transport model for ionic polymer metal composite actuators in large bending deformations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagawa, H.; Kojima, I.; Torii, S.; Lin, W.; Sasaki, M. Bending Controllable IPMC Requires the Particular Structure Silver Electrodes as Well as Dehydration Treatment and Imposed Charge Quantity Control. Mod. Concept Mater. Sci. 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagawa, T.; Nogata, F.; Watanabe, T.; Abe, A.; Yagasaki, K.; Jin, J.-Y. Influence of metal plating treatment on the electric response of Nafion. J. Mater. Sci. 2003, 34, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagawa, H.; Nogata, F.; Sasaki, M. Charge quantity as a sole factor quantitatively governing curvature of Selemion. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 124, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K.; Sasaki, M.; Tamagawa, H. IPMC bending predicted by the circuit and viscoelastic modelsconsidering individual influence of Faradaic and non-Faradaiccurrents on the bending. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 190, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakita, M.; Kamamichi, N.; Kaneda, Y.; Asaka, K.; Luo, Z.-W. Ipmc Linear Actuator with Re·Doping Capability and Its Application to Biped Walking Robot. IFAC Mechatron. Syst. 2004, 37, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; He, Q.; Zhu, D.; Luo, M. A Compact Review of IPMC as Soft Actuator and Sensor: Current Trends, Challenges, and Potential Solutions From Our Recent Work. Front. Robot. AI 2019, 6, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Howley, E.T. Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2000, 32, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicoira, H.; Zanolla, L.; Franceschini, L.; Rossi, A.; Golia, G.; Zamboni, M.; Tosoni, P.; Zardini, P. Skeletal Muscle Mass Independently Predicts Peak Oxygen Consumption and Ventilatory Response During Exercise in Noncachectic Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 2080–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zwaard, S.; de Ruiter, C.J.; Noordhof, D.A.; Sterrenburg, R.; Bloemers, F.W.; de Koning, J.J.; Jaspers, R.T.; van der Laarse, W.J. Maximal oxygen uptake is proportional to muscle fiber oxidative capacity, from chronic heart failure patients to professional cyclists. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 121, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, G.; Fornasiero, A.; Savoldelli, A.; Bortolan, L.; Rainoldi, A.; Schena, F.; Pellegrini, B. Oxygen consumption and muscle fatigue induced by whole-body electromyostimulation compared to equal-duration body weight circuit training. Sport Sci. Health 2017, 13, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, K.M. The Ubiquitous Biochemical Logic of Murburn Concept. Biomed. Rev. 2018, 29, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, K.M.; Soman, V.; Jacob, V.D.; Parashar, A.; Gideon, D.A.; Kumar, M.; Manekkathodi, A.; Ramasamy, S.; Pakshirajan, K.; Bazhin, N.M. Chemiosmotic and murburn explanations for aerobic respiration: Predictive capabilities, structure-function correlations and chemico-physical logic. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 676, 108128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoj, K.M.; Jacob, V.D. The Murburn Precepts for Photoreception. Biomed. Rev. 2020, 31, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoj, K.M.; Manekkathodi, A. Light’s interaction with pigments in chloroplasts: The murburn perspective. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2021, 5, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Grágeda, M.; Quispe, A.; Ushak, S.; Sistat, P.; Cretin, M. Application and Analysis of Bipolar Membrane Electrodialysis for LiOH Production at High Electrolyte Concentrations: Current Scope and Challenges. Membranes 2021, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, F.; Li, X.; Luo, F.; Li, T.; Yu, W.; Wu, L.; Xu, T. Advanced bipolar membranes with earth-abundant water dissociation catalysts for durable ampere-level water electrolysis. Adv. Membr. 2025, 5, 100152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lughmani, W.A.; Jho, J.Y.; Lee, J.Y.; Rhee, K. AModeling of Bending Behavior of IPMC Beams Using Concentrated Ion Boundary Layer. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2009, 10, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Lin, W.; Tamagawa, H.; Ito, S.; Kikuchi, K. Self-Sensing Control of Nafion-Based Ionic Polymer-Metal Composite (IPMC) Actuator in the Extremely Low Humidity Environment. Actuators 2013, 2, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Klaus, S.; Benziger, J. Wetting and absorption of water drops on Nafion films. Langmuir 2009, 24, 8627–8633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, K.A.; Shin, J.W.; Eastman, S.A.; Rowe, B.W.; Kim, S.; Kusoglu, A.; Yager, K.G.; Stafford, G.R. In Situ Method for Measuring the Mechanical Properties of Nafion Thin Films during Hydration Cycles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 17874–17883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tamagawa, H.; Fujiwara, R.; Kojima, I. High Current Induction for the Effective Bending in Ionic Polymer Metal Composite. Membranes 2025, 15, 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110333

Tamagawa H, Fujiwara R, Kojima I. High Current Induction for the Effective Bending in Ionic Polymer Metal Composite. Membranes. 2025; 15(11):333. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110333

Chicago/Turabian StyleTamagawa, Hirohisa, Rintaro Fujiwara, and Iori Kojima. 2025. "High Current Induction for the Effective Bending in Ionic Polymer Metal Composite" Membranes 15, no. 11: 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110333

APA StyleTamagawa, H., Fujiwara, R., & Kojima, I. (2025). High Current Induction for the Effective Bending in Ionic Polymer Metal Composite. Membranes, 15(11), 333. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15110333