COVID-19 Vaccination in Adults: Results from the Tanzania HIV Impact Survey 2022–2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Variable Definitions

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Study Population

3.2. COVID-19 Vaccination Status

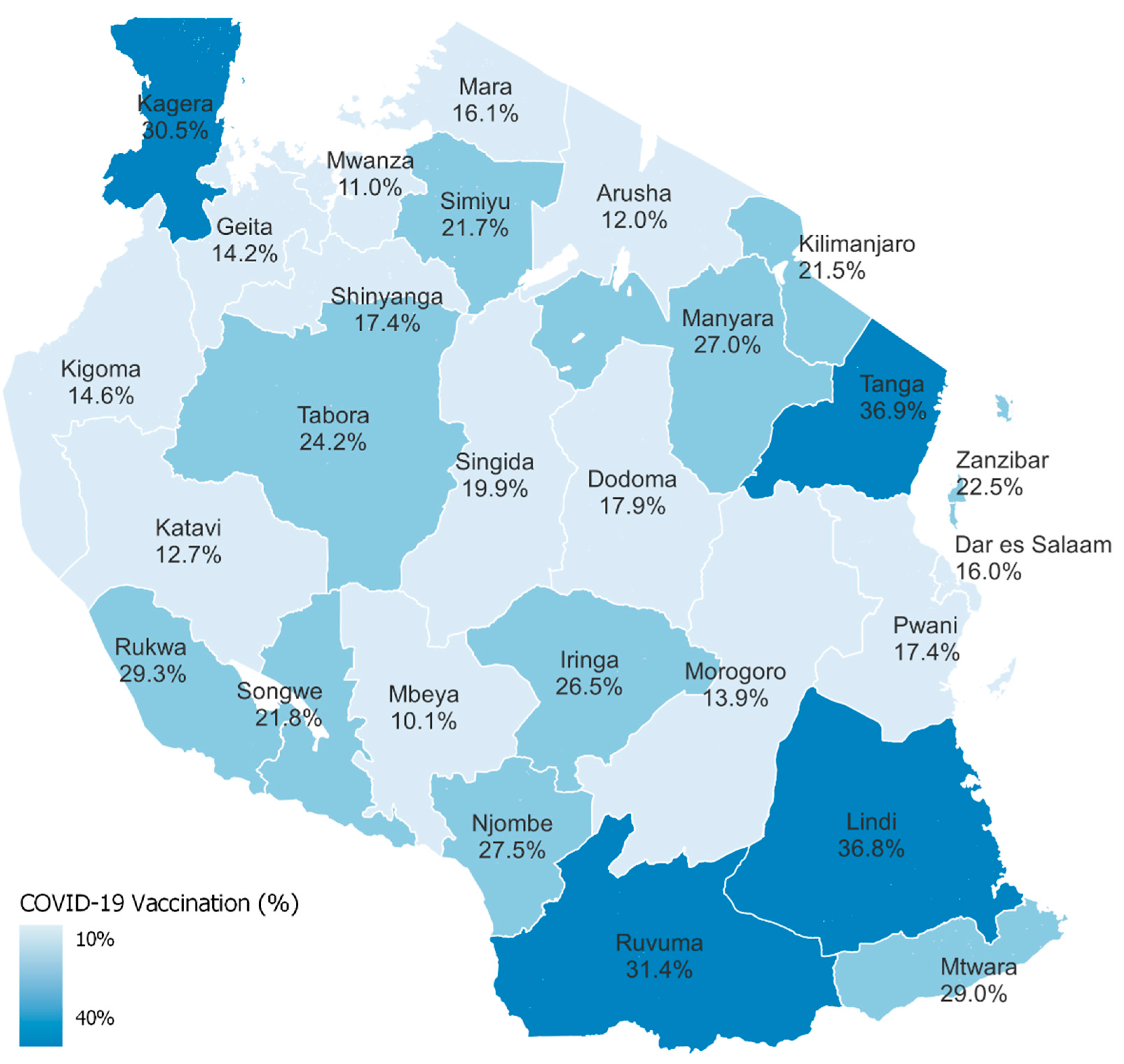

3.3. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake by Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.4. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake by Clinical Characteristics

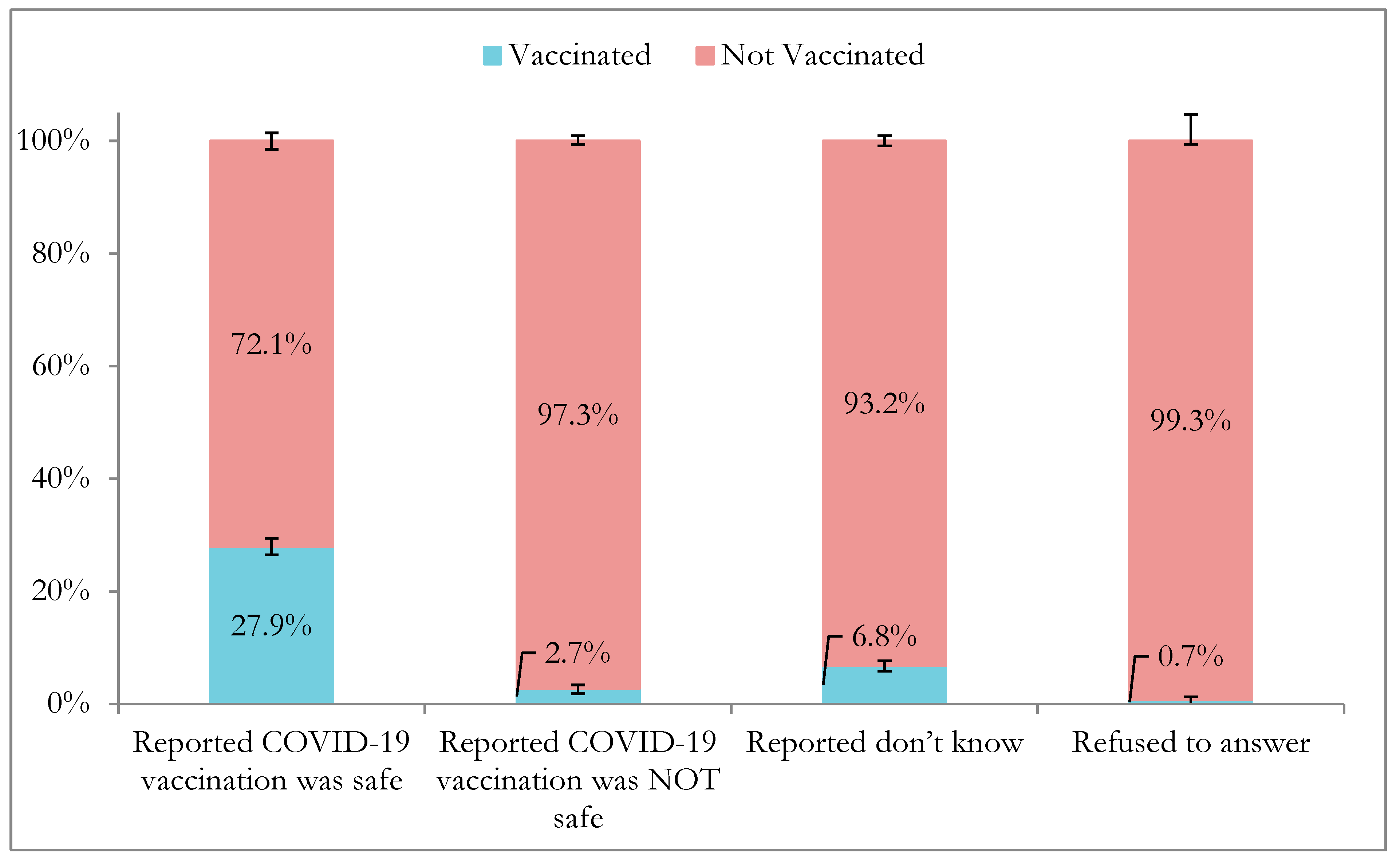

3.5. Perceived Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALHIV | Adults living with HIV |

| ART | Antiretroviral therapy |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| THIS | Tanzania HIV Impact Survey |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Van Espen, M.; Dewachter, S.; Holvoet, N. COVID-19 vaccination willingness in peri-urban Tanzanian communities: Towards contextualising and moving beyond the individual perspective. SSM Popul. Health 2023, 22, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. Guidelines for COVID-19 Vaccination; United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2021.

- Mfinanga, S.G.; Mnyambwa, N.P.; Minja, D.T.; Ntinginya, N.E.; Ngadaya, E.; Makani, J.; Makubi, A.N. Tanzania’s position on the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 397, 1542–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mboya, I.B.; Ngocho, J.S.; Mgongo, M.; Samu, L.P.; Pyuza, J.J.; Amour, C.; Mahande, M.J.; Leyaro, B.J.; George, J.M.; Philemon, R.N.; et al. Community engagement in COVID-19 prevention: Experiences from Kilimanjaro region, Northern Tanzania. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35 (Suppl. 2), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mfinanga, S.G.; Gatei, W.; Tinuga, F.; Mwengee, W.M.P.; Yoti, Z.; Kapologwe, N.; Nagu, T.; Swaminathan, M.; Makubi, A. Tanzania’s COVID-19 vaccination strategy: Lessons, learning, and execution. Lancet 2023, 401, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalloh, M.F.; Tinuga, F.; Dahoma, M.; Rwebembera, A.; Kapologwe, N.A.; Magesa, D.; Mukurasi, K.; Rwabiyago, O.E.; Kazitanga, J.; Miller, A.; et al. Accelerating COVID-19 Vaccination Among People Living With HIV and Health Care Workers in Tanzania: A Case Study. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2024, 12, e2300281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msuya, S.E.; Manongi, R.N.; Jonas, N.; Mtei, M.; Amour, C.; Mgongo, M.B.; Bilakwate, J.S.; Amour, M.; Kalolo, A.; Kapologwe, N.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake and Associated Factors in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from a Community-Based Survey in Tanzania. Vaccines 2023, 11, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children. National Deployment and Vaccination Plan (NDVP) for COVID-19 Vaccine; United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2021.

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC in Tanzania: Program Highlights; CDC Global Health Country Fact Sheet; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023; pp. 4–7.

- Mgongo, M.B.; Manongi, R.N.; Mboya, I.B.; Ngocho, J.S.; Amour, C.; Mtei, M.; Bilakwate, J.S.; Nyaki, A.Y.; George, J.M.; Leyaro, B.J.; et al. A Qualitative Study on Barriers to COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake among Community Members in Tanzania. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Gavrilov, D.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; et al. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. 2020. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- WHO. From Below 10 to 51 Percent—Tanzania Increases COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage. 2023. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/united-republic-of-tanzania/news/below-10-51-percent-tanzania-increases-covid-19-vaccination-coverage (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Buguzi, S.; GAVI. How Tanzania Leapfrogged into the Lead on COVID-19 Vaccination. 2023. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/how-tanzania-leapfrogged-lead-covid-19-vaccination (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Holtzman, C.W.; Godfrey, C.; Ismail, L.; Raizes, E.; Ake, J.A.; Tefera, F.; Okutoyi, S.; Siberry, G.K. PEPFAR’s Role in Protecting and Leveraging HIV Services in the COVID-19 Response in Africa. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2022, 19, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Konje, E.T.; Basinda, N.; Kapesa, A.; Mugassa, S.; Nyawale, H.A.; Mirambo, M.M.; Moremi, N.; Morona, D.; Mshana, S.E. The Coverage and Acceptance Spectrum of COVID-19 Vaccines among Healthcare Professionals in Western Tanzania: What Can We Learn from This Pandemic? Vaccines 2022, 10, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masele, J.J. Misinformation and COVID-19 vaccine uptake hesitancy among frontline workers in Tanzania: Do demographic variables matter? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2324527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msuya, H.M.; Mrisho, G.A.; Mkopi, A.; Mrisho, M.; Lweno, O.N.; Ali, A.M.; Said, A.H.; Mihayo, M.G.; Mswata, S.S.; Tumbo, A.M.; et al. Understanding Sociodemographic Factors and Reasons Associated with COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitance among Adults in Tanzania: A Mixed-Method Approach. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2023, 109, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mtei, M.; Mboya, I.B.; Mgongo, M.; Manongi, R.; Amour, C.; Bilakwate, J.S.; Nyaki, A.Y.; Ngocho, J.; Jonas, N.; Farah, A.; et al. Confidence in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness and safety and its effect on vaccine uptake in Tanzania: A community-based cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2191576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mtenga, S.; Mhalu, G.; Osetinsky, B.; Ramaiya, K.; Kassim, T.; Hooley, B.; Tediosi, F.; Abbas, S.S. Social-political and vaccine related determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Tanzania: A qualitative inquiry. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0002010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yussuph, Z.H.; Al-Beity, F.M.A.; August, F.; Anaeli, A. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women attending public antenatal clinics in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2269777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachathep, K.; Radin, E.P.; Hladik, W.M.; Hakim, A.M.; Saito, S.P.; Burnett, J.; Brown, K.; Phillip, N.; Jonnalagadda, S.P.; Low, A.; et al. Population-Based HIV Impact Assessments Survey Methods, Response, and Quality in Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Zambia. Am. J. Ther. 2021, 87 (Suppl. 1), S6–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Immunization Analysis and Insights. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/immunization-analysis-and-insights/global-monitoring/immunization-coverage/administrative-method (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Cutts, F.T.; Claquin, P.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Rhoda, D.A. Monitoring vaccination coverage: Defining the role of surveys. Vaccine 2016, 34, 4103–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance, Office of Chief Government Statistician President’s Office, Finance, Economy and Development Planning The United Republic of Tanzania. 2012 Population and Housing Census; National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance, Office of Chief Government Statistician President’s Office, Finance, Economy and Development Planning : Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2012.

- Tinuga, F.; Machagge, M.; Conner, R. COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout: Lessons from Tanzania. 2022. Available online: https://www.idsociety.org/science-speaks-blog/2022/covid-19-vaccine-rollout-lessons-from-tanzania (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Nduta, J. Community Engagement Increases COVID-19 Vaccination Rates in Central Tanzania. 2022. Available online: https://usaidmomentum.org/community-engagement-increases-covid-19-vaccination-rates-in-central-tanzania/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Kahn, B.; Brown, L.; Foege, W.; Gayle, H.; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Risk Communication and Community Engagement. In Framework for Equitable Allocation of COVID-19 Vaccine; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, L.E.; Real, F.J.; Cunnigham, J.; Mitchell, M. Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy Using Community-Based Efforts. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 70, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total (%) | % Vaccinated (95% CI *) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 32,477 (100) | 20.0 (18.9–21.1) |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 11,058 (39.1) | 15.5 (14.3–16.7) |

| Rural | 21,419 (60.9) | 22.9 (21.3–24.7) |

| Area | ||

| Tanzania mainland | 30,657 (96.3) | 19.9 (18.8–21.1) |

| Zanzibar | 1820 (3.7) | 22.5 (18.5–27.1) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 13,796 (47.5) | 17.2 (16.1–18.3) |

| Female | 18,681 (52.5) | 22.6 (21.2–24.0) |

| Age, years | ||

| 18–24 | 7306 (25.9) | 12.5 (11.4–13.6) |

| 25–34 | 8367 (27.4) | 18.2 (16.9–19.6) |

| 35–44 | 6252 (18.7) | 22.5 (21.0–24.2) |

| 45–54 | 4705 (13.1) | 25.3 (23.2–27.5) |

| 55–64 | 3006 (7.6) | 29.0 (26.7–31.6) |

| 65+ | 2841 (7.3) | 28.0 (25.5–30.7) |

| Highest Education Level (N = 32,444) | ||

| No education | 5283 (14.4) | 20.9 (18.9–23.1) |

| Primary | 19,259 (57.9) | 21.5 (20.1–22.9) |

| Secondary | 6837 (23.6) | 15.3 (14.2–16.6) |

| Post-secondary | 1065 (4.1) | 22.7 (18.9–27.1) |

| Marital Status (N = 32,442) | ||

| Never married | 5853 (21.8) | 10.9 (9.9–12.0) |

| Married or living together | 20,946 (62.5) | 22.0 (20.6–23.5) |

| Divorced or separated | 3192 (9.6) | 22.4 (20.6–24.3) |

| Widowed | 2451 (6.1) | 28.3 (25.8–30.9) |

| Wealth Quintile (N = 32,464) | ||

| Lowest | 7093 (21.0) | 22.1 (20.0–24.3) |

| Second | 7340 (20.1) | 23.8 (21.6–26.2) |

| Middle | 7150 (20.5) | 20.2 (18.4–22.2) |

| Fourth | 5754 (19.1) | 17.9 (16.3–19.6) |

| Highest | 5127 (19.3) | 15.6 (14.1–17.3) |

| Variable | n | Weighted % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Provided vaccination record | ||

| Yes | 4120 | 57.3 (55.2–59.4) |

| No | 2398 | 42.7 (40.6–44.8) |

| Number of vaccine doses received, of those vaccinated | ||

| 1 | 5073 | 71.5 (68.6–74.3) |

| 2 | 1895 | 27.0 (24.3–29.9) |

| 3+ | 40 | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) |

| Refused/Do not know | 50 | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) |

| Brand of first vaccine dose | ||

| Johnson and Johnson/Janssen | 4311 | 61.2 (58.1–64.1) |

| Pfizer (Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) | 664 | 9.6 (8.12–11.3) |

| Sinopharm (Sinopharm, Beijing, China) | 1017 | 14.8 (13.1–16.7) |

| Moderna (Moderna, MA, USA) | 44 | 0.7 (0.3–1.8) |

| Sinovac (Sinovac, Beijing, China) | 74 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) |

| Refused/Do not know which vaccine was received/other | 948 | 12.9 (11.5–14.5) |

| Completed 2-dose vaccine series (N = 1798) | ||

| Yes | 1520 | 84.2 (81.0–87.1) |

| No | 278 | 15.7 (12.9–19.0) |

| Completed primary vaccine series * | ||

| Yes | 5831 | 83.0 (81.3–84.6) |

| No | 278 | 4.1 (3.4–4.9) |

| Refused/Do not know which vaccine was received | 949 | 13.0 (11.6–14.5) |

| Variables | Total (%) | % Vaccinated (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| HIV Status (N = 32,477) | ||

| Positive | 1823 (4.6) | 49.6 (47.1–52.1) |

| Negative | 28,564 (88.1) | 18.7 (17.6–20.0) |

| Not tested | 2090 (7.4) | 16.7 (14.8–21.2) |

| Other chronic conditions * | ||

| Diabetes | 352 (1.1) | 32.4 (27.0–38.3) |

| Hypertension | 1307 (3.6) | 30.9 (27.5–34.5) |

| Heart disease | 319 (0.8) | 29.8 (23.7–36.7) |

| Kidney disease | 138 (0.4) | 20.6 (15.0–27.6) |

| Cancer or tumor | 306 (0.8) | 24.8 (19.0–21.2) |

| Lung disease | 233 (0.6) | 27.3 (20.9–34.7) |

| Mental health condition | 78 (0.2) | 24.5 (14.5–38.2) |

| No chronic conditions | 29,814 (92.4) | 19.5 (18.4–20.7) |

| Number of years since initiating ART ** (N = 1424) | ||

| Less than 1 year | 128 (9.7) | 46.0 (35.6–57.4) |

| 1 year to less than 5 | 482 (32.9) | 53.7 (48.6–58.6) |

| 5 years to less than 10 | 431 (30.3) | 55.9 (50.0–61.7) |

| 10 years or more | 383 (27.1) | 65.2 (59.1–70.9) |

| Variable | Total (%) | % Vaccinated (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived COVID-19 vaccine safety | ||

| Safe | 21,338 (65.5) | 27.9 (26.4–29.3) |

| Very safe | 12,349 (37.3) | 40.0 (38.1–42.0) |

| Moderately safe | 5616 (17.6) | 13.5 (12.1–15.1) |

| A little safe | 3373 (10.7) | 9.0 (7.6–10.6) |

| Not safe | 4089 (13.3) | 2.7 (2.0–3.6) |

| Do not know | 6825 (20.5) | 6.8 (5.9–7.8) |

| Refused | 225 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.1–5.4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Damian, D.J.; Cosmas, S.G.; Wang, A.; Kagashe, M.; Haji, A.; Rwehumbiza, J.; Issa, F.; Khatib, A.; Karugendo, E.; Mchau, G.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination in Adults: Results from the Tanzania HIV Impact Survey 2022–2023. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121185

Damian DJ, Cosmas SG, Wang A, Kagashe M, Haji A, Rwehumbiza J, Issa F, Khatib A, Karugendo E, Mchau G, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination in Adults: Results from the Tanzania HIV Impact Survey 2022–2023. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121185

Chicago/Turabian StyleDamian, Damian Jeremia, Stephano G. Cosmas, Alice Wang, Magreth Kagashe, Aisha Haji, Jocelyn Rwehumbiza, Fahima Issa, Ahmed Khatib, Emilian Karugendo, Geofrey Mchau, and et al. 2025. "COVID-19 Vaccination in Adults: Results from the Tanzania HIV Impact Survey 2022–2023" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121185

APA StyleDamian, D. J., Cosmas, S. G., Wang, A., Kagashe, M., Haji, A., Rwehumbiza, J., Issa, F., Khatib, A., Karugendo, E., Mchau, G., Sumba, S., Laws, R., Mayige, M., Schaad, N., Kamwela, J., Faki, F., Kakiziba, D. M., Moremi, N., Swaminathan, M., ... Pendo, P. (2025). COVID-19 Vaccination in Adults: Results from the Tanzania HIV Impact Survey 2022–2023. Vaccines, 13(12), 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121185