Mandate or Not Mandate: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 Immunization at the Beginning of Vaccination Campaign

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire

2.2.1. Individual Characteristics

2.2.2. Knowledge Test

2.2.3. Risk Perception

2.2.4. Attitudes and Practices

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

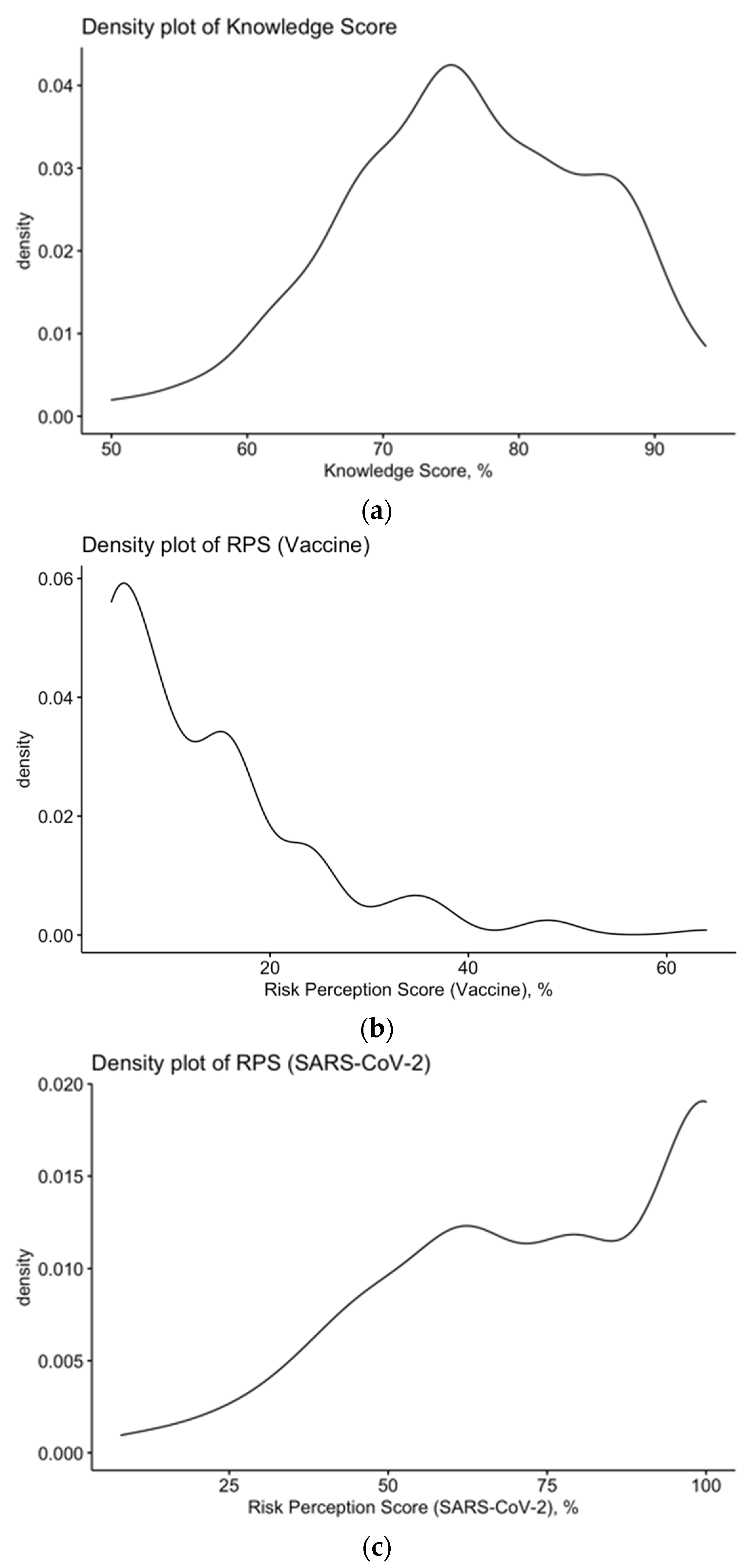

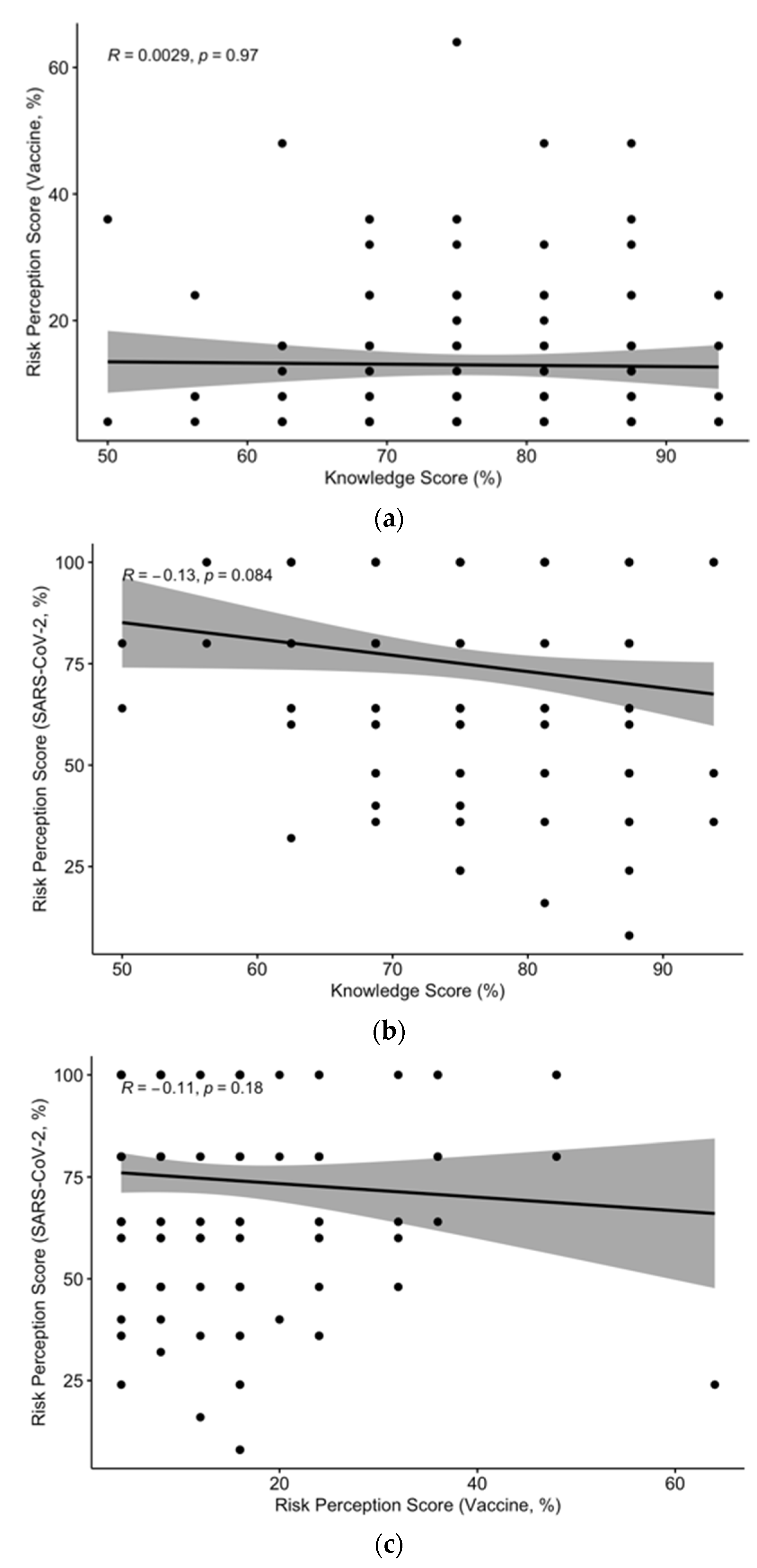

3.2. Assessment of Knowledge about SARS-CoV-2

3.3. Assessment of Attitudes and Practices

3.4. Assessment of the Risk Perception

3.5. Perceived Facilitators and Barriers

3.6. Univariate Analysis

3.7. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reiter, P.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Katz, M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peretti-Watel, P.; Seror, V.; Cortaredona, S.; Launay, O.; Raude, J.; Verger, P.; Beck, F.; Legleye, S.; L’Haridon, O.; Ward, J. A future vaccination campaign against COVID-19 at risk of vaccine hesitancy and politicisation. Lancet 2020, 20, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. European Centre for Diseases Prevention and Control (ECDC) COVID-19 Vaccination and Prioritisation Strategies in the EU/EEA; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/covid-19-vaccination-and-prioritisation-strategies-eueea (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- ECDC. European Centre for Diseases Prevention and Control (ECDC) Key Aspects Regarding the Introduction and Prioritisation of COVID-19 Vaccination in the EU/EEA and the UK; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/key-aspects-regarding-introduction-and-prioritisation-covid-19-vaccination (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 MRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the MRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 384, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneux-Brunon, A.; Detoc, M.; Bruel, S.; Tardy, B.; Rozaire, O.; Frappe, P.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: A cross-sectional survey. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 108, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verger, P.; Scronias, D.; Fradier, Y.; Meziani, M.; Ventelou, B. Online study of health professionals about their vaccination attitudes and behavior in the COVID-19 era: Addressing participation bias. Hum Vaccin Immnother. 2021. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostin, L.O.; Salmon, D.A.; Larson, H.J. Mandating COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA 2020, 325, 532–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verger, P.; Dubé, E. Restoring confidence in vaccines in the COVID-19 Era. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2020, 19, 991–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Wicker, S. Personal attitudes and misconceptions, not official recommendations guide occupational physicians’ vaccination decisions. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4478–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Cattani, S.; Casagranda, F.; Gualerzi, G.; Signorelli, C. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of occupational physicians towards vaccinations of health care workers: A cross sectional pilot study in North-Eastern Italy. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2017, 30, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Gualerzi, G.; Ranzieri, S.; Ferraro, P.; Bragazzi, N.L. Knowledge, attitudes, practices (KAP) of Italian occupational physicians towards tick borne encephalitis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falato, R.; Ricciardi, S.; Franco, G. Influenza risk perception and vaccination attitude in medical and nursing students during the vaccination campaigns of 2007/2008 (seasonal influenza) and 2009/2010 (H1N1 influenza). Med. Lav. 2011, 102, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

- La Torre, G.; Scalingi, S.; Garruto, V.; Siclari, M.; Chiarini, M.; Mannocci, A. Knowledge, attitude and behaviours towards recommended vaccinations among healthcare workers. Healthcare 2017, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loulergue, P.; Moulin, F.; Vidal-Trecan, G.; Absi, Z.; Demontpion, C.; Menager, C.; Gorodetsky, M.; Gendrel, D.; Guillevin, L.; Launay, O. Knowledge, attitudes and vaccination coverage of healthcare workers regarding occupational vaccinations. Vaccine 2009, 27, 4240–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, E.; Izaute, M.; Baggioni, N.C. How can the health belief model and self-determination theory predict both influenza vaccination and vaccination intention? A longitudinal study among university students. Psychol. Health 2017, 33, 746–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccò, M.; Vezzosi, L.; Balzarini, F.; Bragazzi, N.L. Inappropriate risk perception for SARS-CoV-2 infection among Italian HCWs in the Eve of COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, e2020040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, F.J.; Stone, E.R. The risk construct. In Risk-Taking Behaviour; Yates, F.J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1992; pp. 1–25. ISBN 0471922501. [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette of the Italian Republic. 2008. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/gazzetta/serie_generale/caricaDettaglio?dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2008-03-31&numeroGazzetta=76&tipoSerie=serie_generale (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Rothstein, M.A.; Parmet, W.E.; Reiss, D.R. Employer-mandated vaccination for COVID-19. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1061–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largent, E.A.; Persad, G.; Sangenito, S.; Glickman, A.; Boyle, C.; Emanuel, E.J. US public attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccine mandates. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2033324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbatucci, M.; Odone, A.; Signorelli, C.; Siddu, A.; Maraglino, F.; Rezza, G. Improved temporal trends of vaccination coverage rates in childhood after the mandatory vaccination act, Italy 2014–2019. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, L.Y.; Cerda, A.A. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine: A multifcatorial consideration. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, M.; Nakamura, I.; Kojima, T.; Saito, R.; Nakaya, T.; Hanibuchi, T.; Takamiya, T.; Odagiri, Y.; Fukushima, N.; Kikuchi, H.; et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines 2021, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannouchos, T.V.; Steletou, E.; Saridi, M.; Souliotis, K. Mandatory vaccination support and intentions to get vaccinated for COVID-19: Results from a nationally representative general population survey in October 2020 in Greece. J. Eval. Clin. Prat. 2021, 27, 996–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterlini, M. On the front lines of coronavirus: The Italian response to Covid-19. BMJ 2020, 368, m1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaccino, 300 Operatori Sanitari E Medici Fanno Ricorso Al Tar Contro L’obbligo: «Battaglia Democratica»; Il Messaggero Online: Rome, Italy, 2021. Available online: https://www.ilmessaggero.it/salute/storie/vaccino_obbligatorio_medici_operatori_sanitari_ricorso_tar_brescia_ultime_notizie_news-6059550.html (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Signorelli, C.; Guerra, R.; Siliquini, R.; Ricciardi, W. Italy’s response to vaccine hesitancy: An innovative and cost effective national immunization plan based on scientific evidence. Vaccine 2017, 35, 4057–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccò, M.; Cattani, S.; Veronesi, L.; Colucci, M.E. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of construction workers towards tetanus vaccine in Northern Italy. Ind. Health 2016, 54, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riccò, M.; Cattani, S.; Casagranda, F.; Gualerzi, G.; Signorelli, C. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices of occupational physicians towards seasonal influenza vaccination: A cross-sectional study from North-Eastern Italy. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2017, 58, E141–E154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ledda, C.; Costantino, C.; Cuccia, M.; Maltezou, H.; Rapisarda, V. Attitudes of healthcare personnel towards vaccinations before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Vezzosi, L.; Gualerzi, G.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Balzarini, F. Pertussis immunization in healthcare workers working in pediatric settings: Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of occupational physicians. Preliminary Results from a Web-Based Survey (2017). J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2020, 61, E66–E75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, G.; di Giovanni, P.; di Girolamo, A.; Scampoli, P.; Cedrone, F.; D’Addezio, M.; Meo, F.; Romano, F.; di Sciascio, M.B.; Staniscia, T. Knowledge and attitude towards vaccination among healthcareworkers: A multicenter cross-sectional study in a Southern Italian Region. Vaccines 2020, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durando, P.; Dini, G.; Massa, E.; la Torre, G. Tackling biological risk in the workplace: Updates and prospects regarding vaccinations for subjects at risk of occupational exposure in Italy. Vaccines 2019, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spagnolo, L.; Vimercati, L.; Caputi, A.; Benevento, M.; de Maria, L.; Ferorelli, D.; Solarino, B. Role and tasks of the occupational physician during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicina 2021, 57, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, G.; Montecucco, A.; Rahmani, A.; Barletta, C.; Pellegrini, L.; Debarbieri, N.; Orsi, A.; Caligiuri, P.; Varesano, S.; Manca, A.; et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: A cross-sectional study among medical school physicians and residents employed in a regional reference teaching hospital in Northern Italy. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2021, 34, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Gualerzi, G.; Ranzieri, S.; Henry, B.M.; Said, Y.B.; Pyatigorskaya, N.V.; Nevolina, E.; Wu, J.; Bragazzi, N.L.; et al. Point-of-care diagnostic tests for detecting SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: A systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world data. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and receptivity for Covid-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review. Vaccines 2021, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Valerio, Z.; Montalti, M.; Guaraldi, F.; Tedesco, D.; Nreu, B.; Mannucci, E.; Monami, M.; Gori, D. Trust of Italian healthcare professionals in covid-19 (anti-sars-cov-2) vaccination. Ann. Ig. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34328496/ (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Soares, P.; Rocha, V.; Moniz, M.; Gama, A.; Laires, P.A.; Pedro, A.R. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, V.C.; Kelekar, A.; Afonso, N.M. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J. Public Health. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33367857/ (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Shekhar, R.; Sheikh, A.B.; Upadhyay, S.; Singh, M.; Kottewar, S.; Mir, H.; Barrett, E.; Pal, S. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health care workers in the United States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmon, D.A. Mandating COVID-19 vaccines mandating COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA 2020, 325, 532–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K.C.; Ryan, P.; Howard, D.E.; Feldman, K.A. Understanding knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors toward west nile virus prevention: A survey of high-risk adults in Maryland. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2018, 18, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzieciolowska, S.; Hamel, D.; Gadio, S.; Dionne, M. Covid-19 vaccine acceptance, hesitancy, and refusal among canadian healthcare workers: A multicenter survey. Am. J. Infect. Control 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verger, P.; Scronias, D.; Dauby, N.; Adedzi, K.A.; Gobert, C.; Bergeat, M.; Gagneur, A.; Dubé, E. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: A survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Euro Surveill. 2021, 26, 2002047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, D.; Schmidt-Petri, C.; Schröder, C. Attitudes on voluntary and mandatory vaccination against COVID-19: Evidence from Germany. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Vo, T.Q.; et al. Willingness-to-pay for a COVID-19 vaccine and its associated determinants in Indonesia. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Theodoridou, K.; Ledda, C.; Rapisarda, V.; Theodoridou, M. Vaccination of healthcare workers: Is mandatory vaccination needed? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2019, 18, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Update Vaxzevria AstraZeneca AB; EMA: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2021; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/vaxzevria-previously-covid-19-vaccine-astrazeneca (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Pottegård, A.; Lund, L.C.; Karlstad, Ø.; Dahl, J.; Andersen, M.; Hallas, J.; Lidegaard, Ø.; Tapia, G.; Gulseth, H.L.; Ruiz, P.L.D.; et al. Arterial events, venous thromboembolism, thrombocytopenia, and bleeding after vaccination with oxford-astrazeneca ChAdOx1-S in Denmark and Norway: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2021, 373, n1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Coronavirus: Towards a Common Vaccination Strategy; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_20_1913 (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Overview of EU/EEA Country Recommendations on COVID-19 Vaccination with Vaxzevria, and a Scoping Review of Evidence to Guide Decision-Making; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Overview%20EU%20EEA%20country%20recommendations%20on%20COVID-19%20vaccination%20Vaxzevria%20and%20scoping%20review%20of%20evidence.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Rollout of COVID-19 Vaccines in the EU/EEA: Challenges and Good Practice Key Findings; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021; Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/rollout-covid-19-vaccines-eueea-challenges-and-good-practice (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Di Gennaro, F.; Murri, R.; Segala, F.V.; Cerruti, L.; Abdulle, A.; Saracino, A.; Bavaro, D.F.; Fantoni, M. Attitudes towards Anti-Sars-Cov2 vaccination among healthcare workers: Results from a national survey in Italy. Viruses 2021, 13, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmyd, B.; Karuga, F.F.; Bartoszek, A.; Staniecka, K.; Siwecka, N.; Bartoszek, A.; Błaszczyk, M.; Radek, M. Attitude and behaviors towards Sars-Cov-2 vaccination among healthcareworkers: A cross-sectional study from Poland. Vaccines 2021, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, C.; Maillard, A.; Bodelet, C.; Claudel, A.-L.; Gaillat, J.; Delory, T. Hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers: A multi-centric survey in France. Vaccines 2021, 9, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharpure, R.; Guo, A.; Krier Bishnoi, C.; Patel, U.; Gifford, D.; Tippins, A.; Jaffe, A.; Shulman, E.; Stone, N.; Mungai, E.; et al. Early COVID-19 First-Dose Vaccination Coverage Among Residents and Staff Members of Skilled Nursing Facilities Participating in the Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program-United States, December 2020–January 2021. MMWR 2021, 70, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yaqub, O.; Castle-Clarke, S.; Sevdalis, N.; Chataway, J. Attitudes to vaccination: A critical review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 112, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaushal, S.; Rajput, A.S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Vidyasagar, M.; Kumar, A.; Prakash, M.K.; Ansumali, S. Estimating the herd immunity threshold by accounting for the hidden asymptomatics using a COVID-19 specific model. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, K.O.; Mcneil, E.B.; Tsoi, M.T.F.; Wei, V.W.I.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Tang, J.W.T. Will achieving herd immunity be a road to success to end the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Infect. Available online: https://www.journalofinfection.com/article/S0163-4453(21)00287-5/fulltext (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Spinewine, A.; Pétein, C.; Evrard, P.; Vastrade, C.; Laurent, C.; Delaere, B.; Henrard, S. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination among hospital staff—Understanding what matters to hesitant people. Vaccines 2021, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulla, Z.A.; Al-Bashir, S.M.; Al-Salih, N.S.; Aldamen, A.A.; Abdulazeez, M.Z. A summary of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and technologies available or under development. Pathogens 2021, 10, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.; Stoker, G.; Bunting, H.; Valgarðsson, V.O.; Gaskell, J.; Devine, D.; McKay, L.; Mills, M.C. Lack of trust, conspiracy beliefs, and social media use predict COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guljaš, S.; Bosnić, Z.; Salha, T.; Berecki, M.; Krivdić Dupan, Z.; Rudan, S.; Majnarić Trtica, L. Lack of informations about COVID-19 vaccine: From implications to intervention for supporting public health communications in COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craxì, L.; Casuccio, A.; Amodio, E.; Restivo, V. Who should get COVID-19 vaccine first? A survey to evaluate hospital workers’ opinion. Vaccines 2021, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Peng, Z.; Luo, W.; Si, S.; Mo, M.; Zhou, H.; Xin, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, Y. Efficacy and safety of Covid-19 vaccines in phase Iii trials: A meta-analysis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANSA. COVID: Italy’s Vaccination Campaign Struggling to Take Off; ANSA: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: https://www.ansa.it/english/news/general_news/2021/03/22/covid-italys-vaccination-campaign-struggling-to-take-off_fec3657b-34fe-4c71-b37f-e9c2c411b652.html (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Eyre, D.W.; Lumley, S.F.; Donnell, D.O.; Campbell, M.; Sims, E.; Warren, F.; James, T.; Cox, S.; Howarth, A.; Doherty, G.; et al. Differential occupational risks to healthcare workers from SARS-CoV- 2: A prospective observational study. Elife 2020, 9, e60675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, R.; Nagel, S.; Nickel, O.; Wolf, J.; Kalbitz, S.; Kaiser, T.; Borte, S.; Lübbert, C. Comprehensive investigation of an in-hospital transmission cluster of a symptomatic SARS-CoV-2–positive physician among patients and healthcare workers in Germany. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, G.; Pelullo, C.P.; Della Polla, G.; Montemurro, M.V.; Napolitano, F.; Pavia, M.; Angelillo, I.F. Surveying willingness towards SARS-CoV-2 vaccination of healthcare workers in Italy. Expert Rev. Vaccines. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14760584.2021.1922081 (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Olalla, J.; Correa, A.M.; Martín-Escalante, M.D.; Hortas, M.L.; Martín-Sendarrubias, M.J.; Fuentes, V.; Sena, G.; Garcia-Alegria, J. Search for asymptomatic carriers of SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare workers during the pandemic: A Spanish experience. QJM 2020, 113, hcaa238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canova, V.; Lederer Schlpfer, H.; Piso, R.J.; Droll, A.; Fenner, L.; Hoffmann, T.; Hoffmann, M. Transmission risk of SARS-CoV-2 to healthcare workers–observational results of a primary care hospital contact tracing. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2020, 150, w20257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivett, L.; Routledge, M.; Sparkes, D.; Warne, B.; Bartholdson, J.; Cormie, C.; Forrest, S.; Gill, H. Screening of healthcare workers for SARS-CoV-2 highlights the role of asymptomatic carriage in COVID-19 transmission. eLife 2020, 9, e58728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccò, M.; Peruzzi, S.; Balzarini, F. Public Perceptions on Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions for West Nile Virus Infections: A Survey from an Endemic Area in Northern Italy. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiervang, E.; Goodman, R. Advantages and limitations of web-based surveys: Evidence from a child mental health survey. Soc. Psychiat. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, S.; Lei, W.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Yao, D.; Xu, Y.; Lv, Q.; Hao, G.; Xu, Y.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding zika: Paper and internet based survey in Zhejiang, China. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017, 3, e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Statistics on the Health institution in Italy. Available online: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCIS_OSPEDSSN (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Manzoli, L.; Sotgiu, G.; Magnavita, N.; Durando, P.; Barchitta, M.; Carducci, A.; Conversano, M.; de Pasquale, G.; Dini, G.; Firenze, A.; et al. Evidence-based approach for continuous improvement of occupational health. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 39, S81–S85. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | No., % | Average ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 67 (40.4%) | |

| Female | 99 (59.6%) | |

| Age (years) | 49.1 ± 10.7 | |

| Age ≥ 50 years | 60 (36.1%) | |

| Seniority (years) | 22.2 ± 10.3 | |

| Seniority ≥ 15 years | 134 (80.7%) | |

| Working as occupational physician in Hospital(s) affiliated with National Health Service | 98 (59.0%) | |

| Geographical origin | ||

| Northern Italy | 60 (36.1%) | |

| Central Italy | 52 (31.3%) | |

| Southern Italy | 54 (32.5%) | |

| Any previous interaction with SARS-CoV-2 | ||

| Previous diagnosis in him/herself | 17 (10.2%) | |

| Previous diagnosis in relatives | 42 (25.3%) | |

| Information sources | ||

| Conventional media (TV, journals, etc.) | 36 (21.7%) | |

| New media (Wikis, social media, Twitter, etc.) | 28 (16.9%) | |

| Websites from international and governmental agencies | 146 (88.0%) | |

| Friend, relatives | 8 (4.8%) | |

| Colleagues | 3 (1.8%) | |

| Formation courses | 117 (70.5%) | |

| Knowledge score (%) | 76.3 ± 9.3 | |

| Higher knowledge score (>75.0%) | 69 (41.6%) |

| Statement | CORRECT ANSWER | No., % |

|---|---|---|

| More severe cases of COVID-19 occur in subjects ≥ 65 year-old and/or subjects affected by comorbidities | TRUE | 149 (89.8%) |

| Main complications of COVID-19 are represented by respiratory distress syndrome | TRUE | 155 (93.4%) |

| By January 2021, adenovirus-based vaccines were approved by the EMA | FALSE | 73 (44.0%) |

| Present-day case-fatality-ratio of COVID-19 in Italy | ||

| …is greater than 1 out of 10 affected cases (> 10%) | FALSE | 8 (4.8%) |

| …accounts for 1 out of 10 affected cases (~10%) | FALSE | 16 (10.8%) |

| …accounts for 1 out of 100 affected cases (~1%) | TRUE | 66 (39.8%) |

| …accounts for 1 out of 1000 affected cases (~0.1%) | FALSE | 45 (27.1%) |

| …remains unknown | FALSE | 20 (12.0%) |

| mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ComiRNAty™ requires only one vaccination shot | FALSE | 140 (84.3%) |

| Official efficiency of mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ComiRNAty™ is greater than 90% | TRUE | 150 (90.4%) |

| Pleural ultrasonography is an efficient instrument in early diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 interstitial pneumonia | TRUE | 106 (63.9%) |

| SARS-CoV-2 is efficiently transmitted by cough | TRUE | 161 (97.0%) |

| SARS-CoV-2 is mainly transmitted by contaminated blood | FALSE | 154 (92.8%) |

| Hand washing reduces the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infections | TRUE | 160 (96.4%) |

| All cases infected by SARS-CoV-2 develop COVID-19 symptoms | FALSE | 162 (97.6%) |

| An efficient and etiologic treatment for COVID-19 has been made available | FALSE | 147 (88.6%) |

| Latency of COVID-19 may reach 14 days | TRUE | 147 (88.6%) |

| Gold standard for SARS-CoV-2 infection is represented by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction | TRUE | 164 (98.8%) |

| Rapid antigen detection tests for SARS-CoV-2 infection are quite specific but scarcely sensitive | TRUE | 113 (68.1%) |

| Temporarily, RNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ComiRNAty™ cannot be delivered to pregnant women | TRUE | 94 (56.6%) |

| Variable | No., % | Average ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Reported trust in vaccines (high/very high) | 159 (95.8%) | |

| Reported acceptance of SIV (often/always) | 105 (63.3%) | |

| Reported acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines | ||

| mRNA vaccines | 149 (89.8%) | |

| Adenovirus-based vaccines | 85 (51.2%) | |

| any | 150 (90.4%) | |

| How much would you pay for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine? | ||

| Nothing, vaccine should be provided for free | 52 (31.3%) | |

| Participation to the expenditure | 49 (29.5%) | |

| Up to EUR 10/dose | 9 (5.4%) | |

| Between EUR 10 to 49/dose | 9 (5.4%) | |

| Between EUR 50 to 99/dose | 16 (9.6%) | |

| Between EUR 100 to 199/dose | 16 (9.6%) | |

| EUR 200 or more/dose | 15 (9.0%) | |

| Acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 immunization by means of…(agree/totally agree) | ||

| …vaccines based on inactivated SARS-CoV-2 | 91 (54.8%) | |

| …adenovirus-based vaccines | 85 (51.2%) | |

| …attenuated SARS-CoV-2 | 49 (29.5%) | |

| …vaccines based on SARS-CoV-2 mRNA | 149 (89.8%) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccine should be mandatory? | ||

| No, I think that it is dangerous | 1 (0.6%) | |

| No, it must be performed on a voluntary basis | 36 (21.7%) | |

| No, it must be recommended to high-risk subjects | 1 (0.6%) | |

| No, it must be recommended to high-risk subjects and HCWs | 1 (0.6%) | |

| No, it must be recommended to high-risk subjects and high risk-workers, including HCWs | 27 (16.3%) | |

| Yes, it should be made mandatory | 55 (33.1%) | |

| Yes, it should be made mandatory with fines for hesitant | 45 (27.1%) | |

| Occupational physicians should retain the vaccine-hesitant HCWs as… | ||

| …still fit for work, as PPE are more efficient than vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection | 50 (30.1%) | |

| …unfit for work in high-risk settings, with temporary reassignment to low-risk tasks (if available) | 83 (50.0%) | |

| …unfit for working in healthcare settings, permanently | 33 (19.9%) | |

| Risk perception | ||

| High risk for COVID-19 among occupational physicians | 104 (62.7%) | |

| COVID-19 acknowledged as a common disease | 132 (79.5%) | |

| COVID-19 acknowledged as a severe disease | 136 (81.9%) | |

| mRNA vaccine side effects acknowledged as a frequently reported issue | 7 (4.2%) | |

| mRNA vaccine side effects acknowledged as a severe issue | 9 (5.4%) | |

| Risk perception score for COVID-19 (%) | 74.5 ± 24.3 | |

| Risk perception score for mRNA vaccines (%) | 13.0 ± 10.6 |

| Total (No./166, %) | |

| Perceived barriers | |

| Inappropriate vaccine safety (perceived) | 78 (47.0%) |

| Inappropriate vaccine efficacy (perceived) | 33 (19.9%) |

| Inappropriate vaccine availability | 40 (24.1%) |

| Lack of confidence in NHS | 17 (10.2%) |

| Lack of confidence in NHS personnel | 7 (4.2%) |

| Workers not acknowledging themselves among high-risk groups | 20 (12.0%) |

| COVID-19 not acknowledged as a severe disease | 30 (18.1%) |

| Higher confidence in alternative approach (i.e., hyperimmune plasma) | 9 (5.4%) |

| Higher confidence in alternative approach (i.e., hydroxychloroquine) | 8 (4.8%) |

| Lack of confidence in pharmaceutical industry | 32 (19.3%) |

| Perceived facilitators | |

| Willingness to protect himself/herself | 78 (47.0%) |

| Willingness to protect friends, relatives | 110 (66.3%) |

| Willingness to avoid complications | 57 (34.3%) |

| Willingness to avoid COVID-19 | 60 (36.1%) |

| Workers acknowledging themselves among high-risk groups | 81 (48.8%) |

| COVID-19 acknowledged as a severe disease | 72 (43.4%) |

| Lack of confidence in alternative treatments | 4 (2.4%) |

| Lack of confidence in PPE | 152 (91.6%) |

| Lack of confidence in HCW risk perception | 142 (85.0%) |

| NPI are of limited reliability in healthcare settings | 113 (68.1%) |

| Tracing and tracking of COVID-19 cases are unreliable in healthcare settings | 100 (60.2%) |

| Attitude Towards a Mandatory Status for SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines | Chi Squared Test p Value | aOR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somewhat Favorable (No./100, %) | Somewhat Not Favorable (No./66, %) | |||

| Age ≥ 50 years | 33 (33.0%) | 27 (40.9%) | 0.383 | - |

| Seniority ≥ 15 years | 80 (80.0%) | 54 (81.8%) | 0.929 | - |

| Male sex | 46 (46.0%) | 21 (31.8%) | 0.097 | - |

| Being form Northern Italy | 32 (32.0%) | 28 (42.4%) | 0.229 | - |

| Working as occupational physician in hospital(s) affiliated with National Health Service | 59 (59.6%) | 39 (59.1%) | 1.000 | - |

| Previous diagnosis of COVID-19 in him/herself | 10 (10.0%) | 7 (10.6%) | 1.000 | - |

| Previous diagnosis of COVID-19 in relatives | 25 (25.0%) | 17 (25.8%) | 1.000 | - |

| Perceived high risk for COVID-19 among occupational physicians | 71 (71.0%) | 33 (50.0%) | 0.010 | 2.332 (0.968; 5.617) |

| COVID-19 acknowledged as a common disease | 89 (89.0%) | 43 (65.2%) | < 0.001 | 3.462 (1.060; 11.310) |

| COVID-19 acknowledged as a severe disease | 88 (88.0%) | 48 (72.7%) | 0.022 | 1.617 (0.463; 5.639) |

| mRNA vaccine side effects acknowledged as a frequently reported issue | 3 (3.0%) | 4 (6.1%) | 0.572 | - |

| mRNA vaccine side effects acknowledged as a severe issue | 4 (4.0%) | 5 (7.6%) | 0.519 | - |

| Acceptance of payment/copayment for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | 81 (81.0%) | 33 (50.0%) | < 0.001 | 3.896 (1.607; 9.449) |

| Reported trust in vaccines (high/very high) | 99 (99.0%) | 60 (90.9%) | 0.032 | 2.308 (0.167; 31.825) |

| Reported acceptance of SIV (often/always) | 72 (72.0%) | 33 (50.0%) | 0.007 | 2.091 (0.926; 4.718) |

| Higher knowledge score | 37 (37.0%) | 32 (48.5%) | 0.191 | - |

| Information sources | ||||

| Conventional media (TV, journals, etc.) | 24 (24.0%) | 12 (18.2%) | 0.485 | - |

| New media (Wikis, social media, Twitter, etc.) | 13 (13.0%) | 15 (22.7%) | 0.154 | - |

| Websites from international and governmental agencies | 87 (87.0%) | 59 (89.4%) | 0.826 | - |

| Friend, relatives | 7 (7.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0.213 | - |

| Colleagues | 2 (2.0%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1.000 | - |

| Formation courses | 73 (73.0%) | 44 (66.7%) | 0.483 | - |

| Occupational physicians should retain the vaccine-hesitant HCWs as unfit for work | 83 (83.0%) | 31 (47.0%) | <0.001 | 4.562 (1.935; 10.753) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riccò, M.; Ferraro, P.; Peruzzi, S.; Balzarini, F.; Ranzieri, S. Mandate or Not Mandate: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 Immunization at the Beginning of Vaccination Campaign. Vaccines 2021, 9, 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080889

Riccò M, Ferraro P, Peruzzi S, Balzarini F, Ranzieri S. Mandate or Not Mandate: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 Immunization at the Beginning of Vaccination Campaign. Vaccines. 2021; 9(8):889. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080889

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiccò, Matteo, Pietro Ferraro, Simona Peruzzi, Federica Balzarini, and Silvia Ranzieri. 2021. "Mandate or Not Mandate: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 Immunization at the Beginning of Vaccination Campaign" Vaccines 9, no. 8: 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080889

APA StyleRiccò, M., Ferraro, P., Peruzzi, S., Balzarini, F., & Ranzieri, S. (2021). Mandate or Not Mandate: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Italian Occupational Physicians towards SARS-CoV-2 Immunization at the Beginning of Vaccination Campaign. Vaccines, 9(8), 889. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9080889