N-terminus of Flagellin Fused to an Antigen Improves Vaccine Efficacy against Pasteurella Multocida Infection in Chickens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria Strains

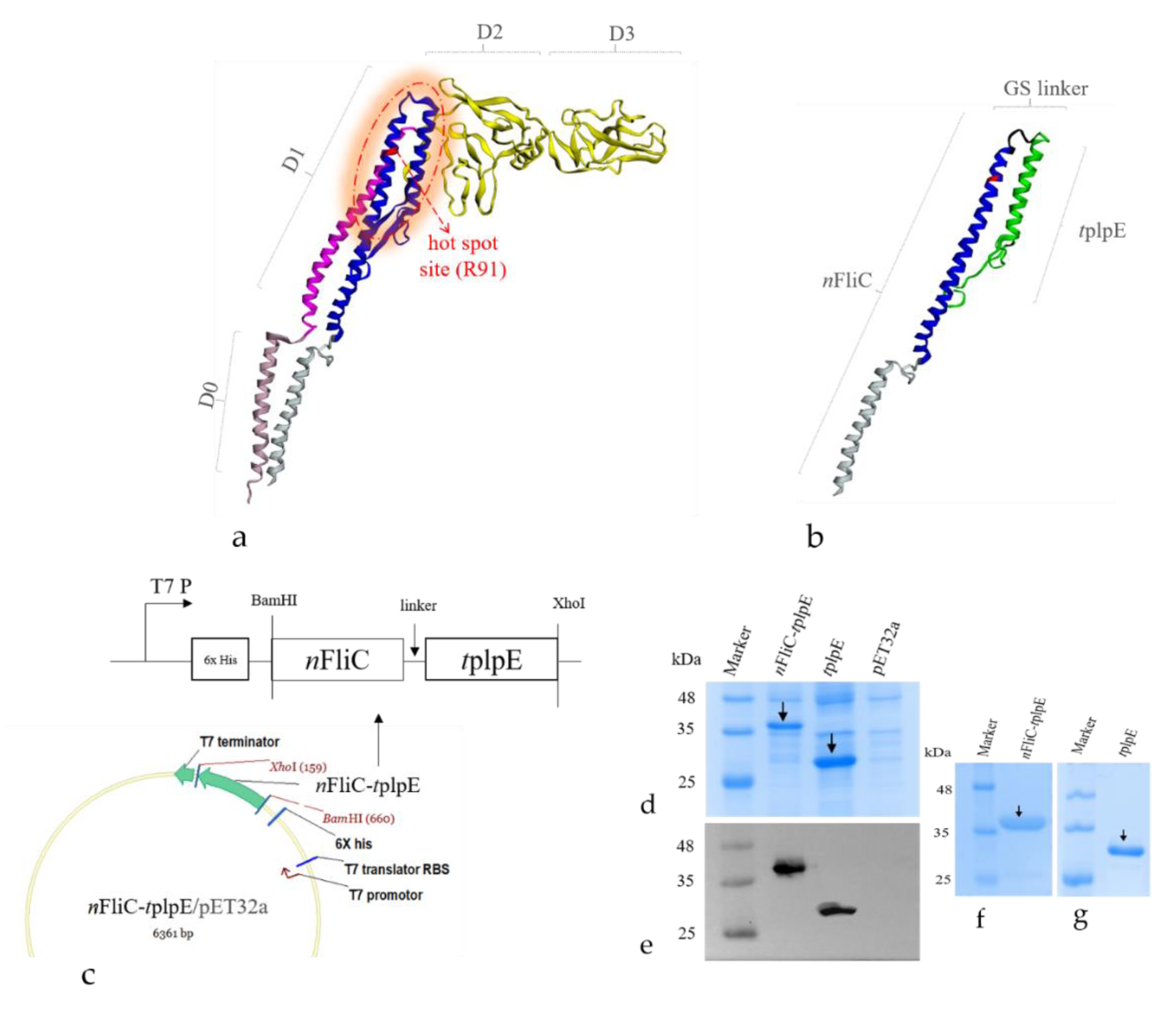

2.2. Plasmid Construction and Protein Expression of Antigen-Adjuvant Recombinant Proteins

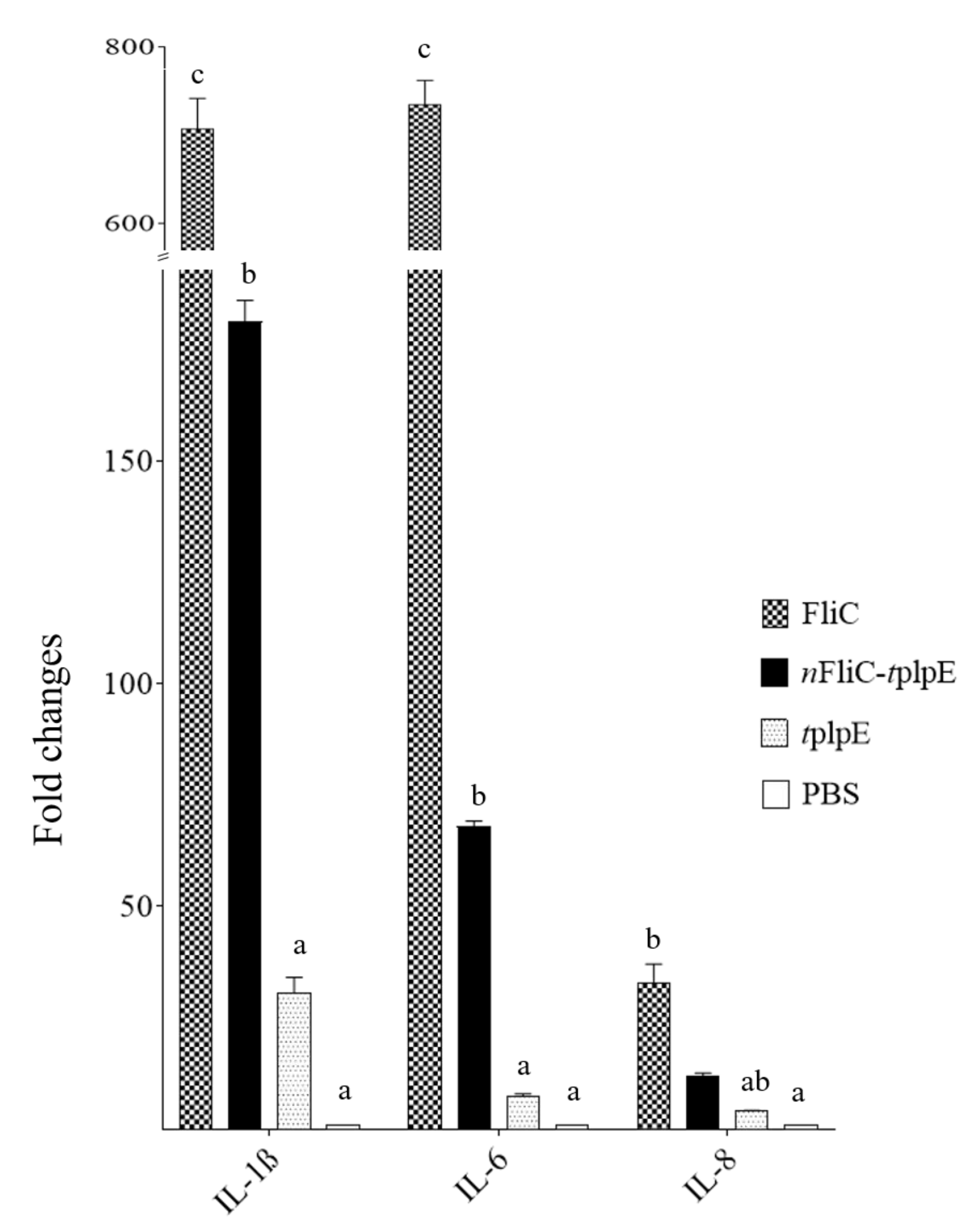

2.3. Analysis of Proinflammatory Cytokine mRNA Levels

2.4. Vaccine Preparation and Immunization

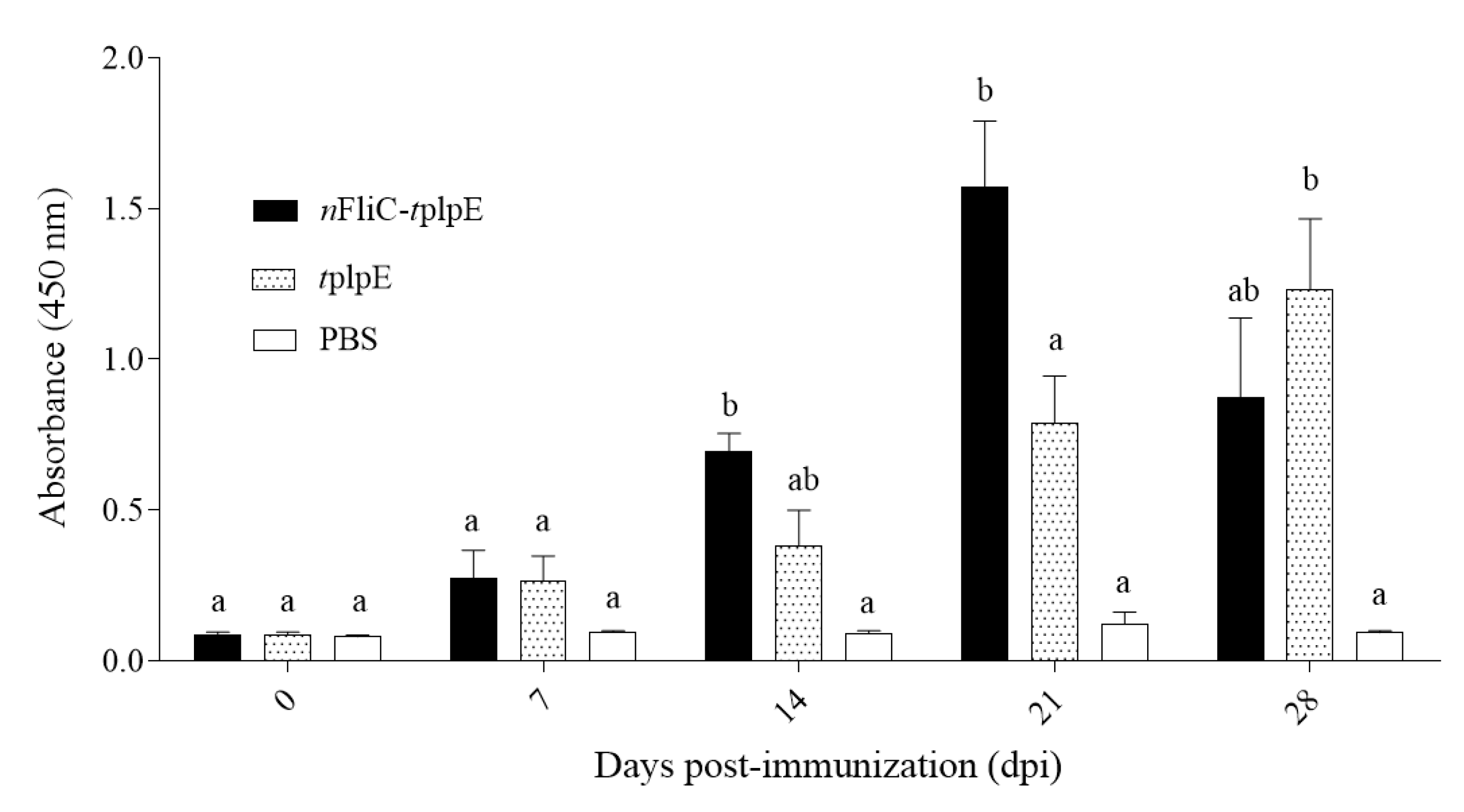

2.5. Analysis of Humoral Immune Response

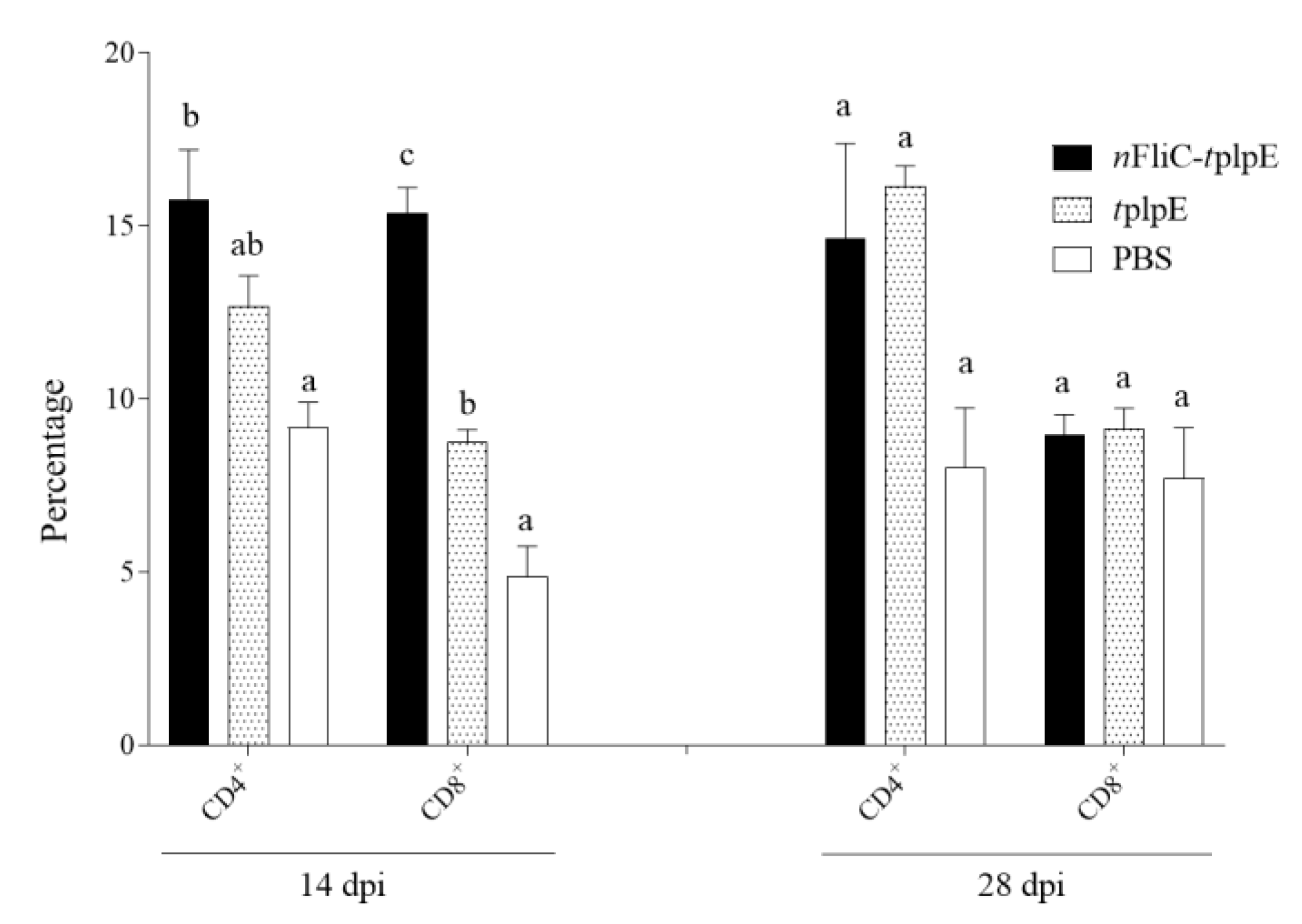

2.6. Analysis of Cellular Immune Response

2.7. Analysis of TH1 and TH2 Type Cytokine mRNA Levels

2.8. P. Multocida Challenge Test

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. An Antigen-Adjuvant Chimeric Protein Was Formulated as a Subunit Vaccine

3.2. N-terminus of Flagellin Enhanced the Proinflammatory Cytokine Gene Expression

3.3. N-terminus of Flagellin Led to a Rapid Rise in Antibody Levels

3.4. N-terminus of Flagellin Enhanced CD8+ T Cell Expansion

3.5. N-terminus of Flagellin Enhanced Gene Expressions of Both TH1 and TH2-Type Cytokines

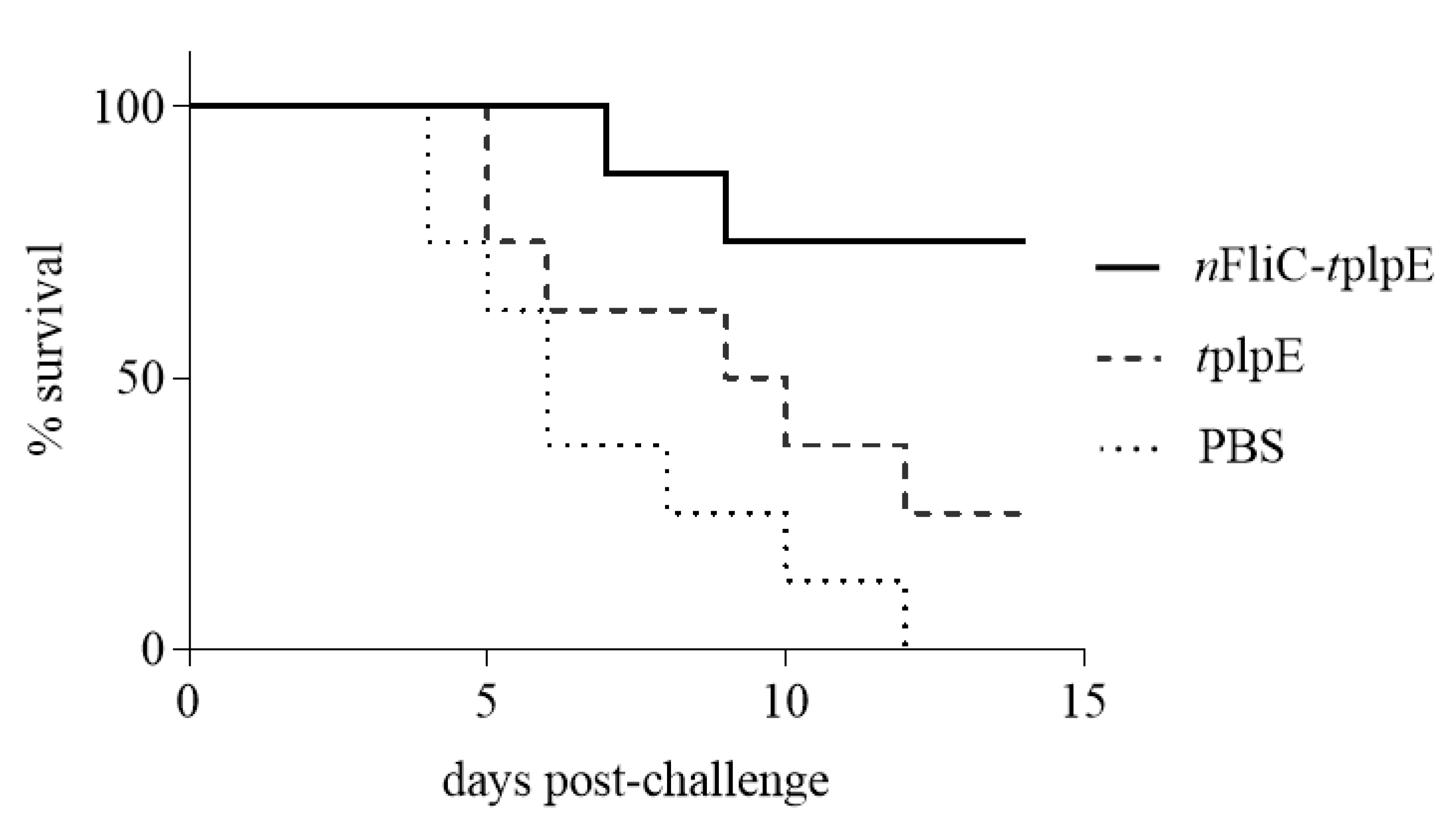

3.6. N-terminus of Flagellin Increased the Survival Rate to 75% in a Challenge Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaban, B.; Hughes, H.V.; Beeby, M. The flagellum in bacterial pathogens: For motility and a whole lot more. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 46, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayan, A.; Rumbo, M.; Carnoy, C.; Sirard, J.-C. Compartmentalized antimicrobial defenses in response to flagellin. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.D.; Andersen-Nissen, E.; Hayashi, F.; Strobe, K.; Bergman, M.A.; Barrett, S.L.R.; Cookson, B.T.; Aderem, A. Toll-like receptor 5 recognizes a conserved site on flagellin required for protofilament formation and bacterial motility. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Moyle, P.M. Bioconjugation approaches to producing subunit vaccines composed of protein or peptide antigens and covalently attached toll-like receptor ligands. Bioconjug. Chem. 2017, 29, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Yang, J.; Zhang, E.; Zhong, M.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhou, D.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y. Activation of NLRC4 downregulates TLR5-mediated antibody immune responses against flagellin. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, F.; Smith, K.D.; Ozinsky, A.; Hawn, T.R.; Eugene, C.Y.; Goodlett, D.R.; Eng, J.K.; Akira, S.; Underhill, D.M.; Aderem, A. The innate immune response to bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature 2001, 410, 1099–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.S. How flagellin and toll-like receptor 5 contribute to enteric infection. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samatey, F.A.; Imada, K.; Nagashima, S.; Vonderviszt, F.; Kumasaka, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Namba, K. Structure of the bacterial flagellar protofilament and implications for a switch for supercoiling. Nature 2001, 410, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonekura, K.; Maki-Yonekura, S.; Namba, K. Complete atomic model of the bacterial flagellar filament by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature 2003, 424, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.S.; Jeon, Y.J.; Namgung, B.; Hong, M.; Yoon, S.-I. A conserved TLR5 binding and activation hot spot on flagellin. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.-I.; Kurnasov, O.; Natarajan, V.; Hong, M.; Gudkov, A.V.; Osterman, A.L.; Wilson, I.A. Structural basis of TLR5-flagellin recognition and signaling. Science 2012, 335, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdelya, L.G.; Krivokrysenko, V.I.; Tallant, T.C.; Strom, E.; Gleiberman, A.S.; Gupta, D.; Kurnasov, O.V.; Fort, F.L.; Osterman, A.L.; DiDonato, J.A. An agonist of toll-like receptor 5 has radioprotective activity in mouse and primate models. Science 2008, 320, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, M.A.; Steiner, T.S. Two nonadjacent regions in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli flagellin are required for activation of toll-like receptor 5. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 40456–40461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaves-Pyles, T.D.; Wong, H.R.; Odoms, K.; Pyles, R.B. Salmonella flagellin-dependent proinflammatory responses are localized to the conserved amino and carboxyl regions of the protein. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 7009–7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savar, N.S.; Jahanian-Najafabadi, A.; Mahdavi, M.; Shokrgozar, M.A.; Jafari, A.; Bouzari, S. In silico and in vivo studies of truncated forms of flagellin (FliC) of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli fused to FimH from uropathogenic Escherichia coli as a vaccine candidate against urinary tract infections. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 175, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savar, N.S.; Sardari, S.; Jahanian-Najafabadi, A.; Bouzari, S. In silico and in vitro studies of truncated forms of flagellin (FliC) of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC). Mol. Inform. 2013, 32, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, K.M.; Boyce, J.D.; Chung, J.Y.; Frost, A.J.; Adler, B. Genetic organization of Pasteurella multocida cap loci and development of a multiplex capsular PCR typing system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizel, S.B.; Bates, J.T. Flagellin as an adjuvant: Cellular mechanisms and potential. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 5677–5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khani, M.-H.; Bagheri, M.; Zahmatkesh, A.; Bidhendi, S.M. Immunostimulatory effects of truncated and full-length flagellin recombinant proteins. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 127, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.; Liu, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Flagellin as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2018, 17, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Doan, T.-D.; Wang, H.-Y.; Ke, G.-M.; Cheng, L.-T. N-terminus of Flagellin Fused to an Antigen Improves Vaccine Efficacy against Pasteurella Multocida Infection in Chickens. Vaccines 2020, 8, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8020283

Doan T-D, Wang H-Y, Ke G-M, Cheng L-T. N-terminus of Flagellin Fused to an Antigen Improves Vaccine Efficacy against Pasteurella Multocida Infection in Chickens. Vaccines. 2020; 8(2):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8020283

Chicago/Turabian StyleDoan, Thu-Dung, Hsian-Yu Wang, Guan-Ming Ke, and Li-Ting Cheng. 2020. "N-terminus of Flagellin Fused to an Antigen Improves Vaccine Efficacy against Pasteurella Multocida Infection in Chickens" Vaccines 8, no. 2: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8020283

APA StyleDoan, T.-D., Wang, H.-Y., Ke, G.-M., & Cheng, L.-T. (2020). N-terminus of Flagellin Fused to an Antigen Improves Vaccine Efficacy against Pasteurella Multocida Infection in Chickens. Vaccines, 8(2), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines8020283