1. Introduction

The contribution of vaccines to reduced morbidity and mortality is one of the great public health success stories [

1,

2]. Broadly, compliance with vaccine recommendations is high in high-income countries and vaccination rates have improved over recent decades in low- and middle-income countries [

3]. Yet this general trend in vaccine success masks underlying complexities in political, logistical, cultural, economic, and social constraints, resulting in unequal immunization rates across populations [

4,

5]. Vaccination faces challenges from a variety of fronts and, as a result, vaccination rates are uneven and questions regarding vaccination are increasing across the globe [

6,

7,

8]. This leads to frequent outbreaks of childhood and adult infectious diseases that could be easily prevented, such as recent measles outbreaks in Wales, United Kingdom and California, United States and endemic polio in Nigeria [

9,

10,

11].

Although individuals were traditionally considered to be “pro”- or “anti”- vaccination, such a dichotomous characterization masks variation and results in missed opportunities to develop customized communication strategies and reach large groups who may be open to vaccination. The diversity of groups along the continuum of beliefs and attitudes towards vaccination prompts attention to “vaccine hesitancy” [

12,

13]. The vaccine-hesitant category includes individuals who are concerned about specific vaccines or vaccination schedules; reject all vaccines, sometimes due to religious or philosophical reasons; do not have specific issues with vaccines, but are concerned based on media and interpersonal communications related to vaccines; have low demand for vaccines because they have not seen the impact of vaccine-preventable diseases; have concerns with trust in/legitimacy of institutions involved with vaccination; and/or are motivated by desires to be informed consumers and advocates for their families’ health [

8,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The drivers of vaccine hesitancy are diverse, including contextual influences (such as culture, healthcare systems, political structures,

etc.); individual and social group influences (such as norms, beliefs,

etc.); and vaccine- and vaccination-specific issues (such as supply and delivery, role of healthcare professionals, costs, health risk and benefit, vaccine exemption policies, and introduction of new vaccines or formulations) [

13].

It is vital to understand the diversity of vaccine-hesitant subgroups to support public health goals of large-scale vaccine uptake. Those who are hesitant, but do not reject all vaccines, are of particular interest from a public health standpoint. This subset is a larger group than those who completely reject vaccines and may be more amenable to changing beliefs and behaviors as they tend to seek out and engage with information about vaccines [

15]. The study of vaccine hesitancy is vital both to address and stem challenges to the successful public health intervention strategy of controlling vaccine-preventable disease, but also in the context of emergency preparedness. Here, we take the example of the H1N1 pandemic response of 2009–2010 in the United States.

The 2009 H1N1 influenza virus (referred to as “H1N1” throughout) emerged and began to spread rapidly across the United States in April of that year. This resulted in a wide-scale emergency response in the United States, which emphasized activation of public health preparedness systems as well as education of the general public regarding this strain of influenza, risks of contracting the virus, and key prevention strategies, including vaccination [

18,

19]. At the outset of the pandemic, approximately half of the public reported they would receive the vaccine and 59%–70% of parents expected to vaccinate their children, according to national polls [

18]. However, by April 2010, only 24% of adults had received the vaccination, well below the rates of regular seasonal influenza vaccination [

20]. This low uptake rate was attributed to a combination of factors, including limited initial vaccine availability, concerns about the safety of what was perceived to be a newly developed vaccine, decreasing perception of susceptibility, and decreasing perception of disease severity. Interestingly, members of the public suggested that the vaccination decision was a trade-off between the potential risk of illness and the potential risk of the vaccine [

18]. Vaccine uptake and its psychosocial antecedents were unevenly distributed across population subgroups [

21]. It is useful to study the vaccine hesitancy continuum in the context of a single vaccine/disease given that attitudes and perceptions are often vaccine- and disease-specific [

22]. In the case of vaccines perceived by the public to be novel—like H1N1—hesitancy may include concerns about safety, side effects, disease severity, the rapid vaccine development process, and financial incentives for vaccine producers [

18,

23].

Despite public concerns, governments and public health agencies must act quickly and effectively to stop pandemic influenza strains from having massive impacts across the globe. Beyond vaccine production and distribution, a major tool in their arsenal is communication. Yet, officials and authorities often utilize a top-down, expert-led approach, with a generic, one-size-fits-all approach [

24]. Such approaches are unlikely to lead to behavior change across population sub-groups. A multi-pronged effort, involving interactive dialogue, interpersonal and mass media communication, and public engagement is likely necessary to support individuals in making decisions about vaccines that are evidence-informed [

15,

22,

25]. Such an effort requires understanding the diverse audiences along the vaccine hesitancy continuum for whom communication/engagement campaigns must be created.

Audience segmentation is a useful method to identify population subgroups and determine effective ways to promote behavior change among these groups. Dividing large, heterogeneous groups into meaningful, more homogeneous subgroups is expected to allow health communication professionals to determine which groups to target and how best to do so. To identify key population subgroups, the population is divided based on patterned responses across key variables, such as attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors [

26,

27,

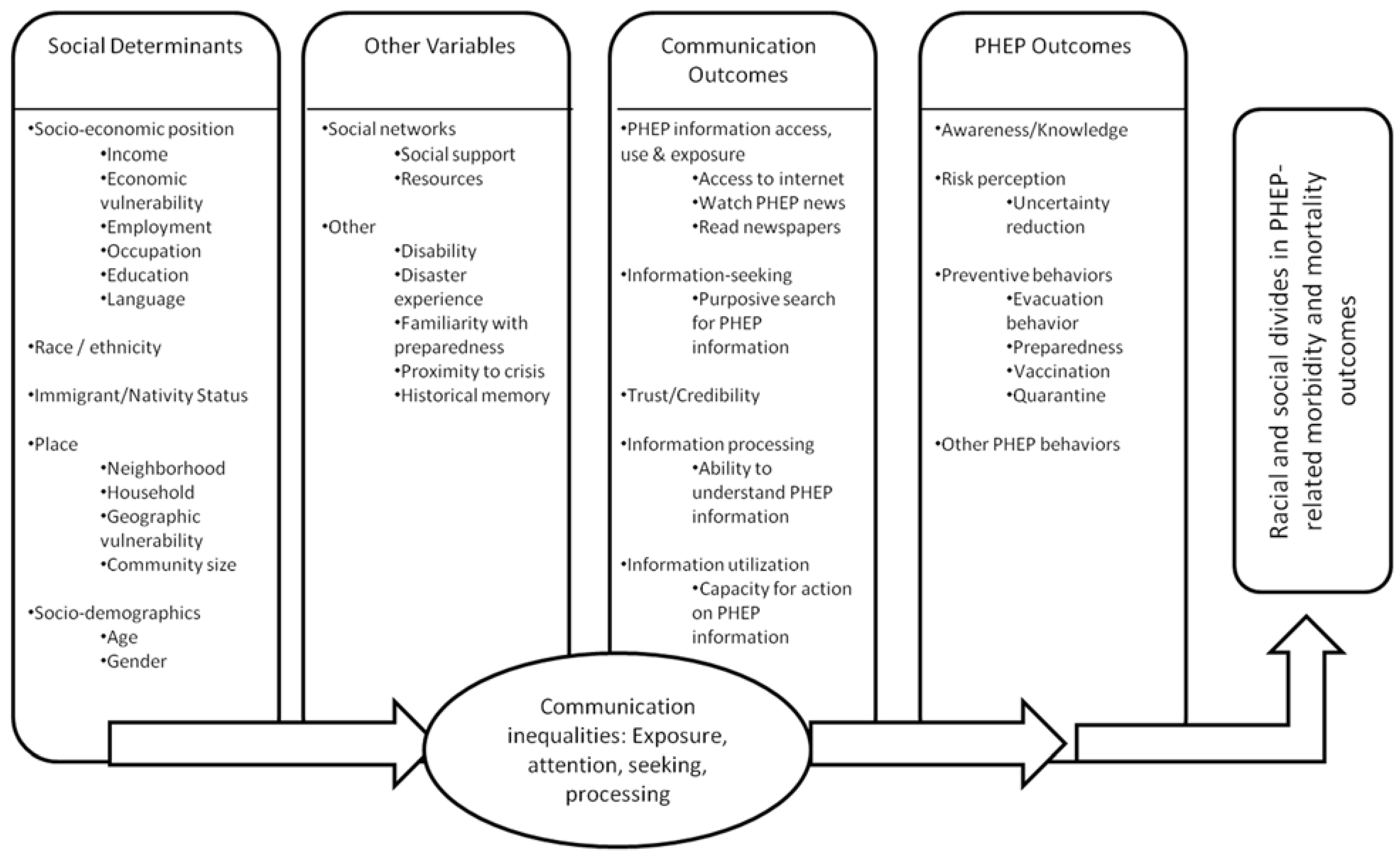

28]. A theory-driven approach for variable selection ensures a targeted selection of these variables. We ground this investigation in the Structural Influence Model (SIM), adapted for Public Health Emergency Preparedness (PHEP) as shown below in

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structural Influence Model of PHEP Communications.

Figure 1.

Structural Influence Model of PHEP Communications.

The SIM posits that inequalities in communication (such as differential exposure to information for population subgroups) mediate the relationship between social determinants (such as socioeconomic position, race/ethnicity, or other factors highlighted in the figure) and health outcomes, thus serving as one potential explanation for health disparities. In other words, health disparities can be understood in part as a function of how (1) structural determinants such as socioeconomic position and (2) moderating mechanisms such as social networks lead to (3) differential communication outcomes, such as access to and use of information channels, attention to health content, recall of information, and capacity to act on relevant information, which in turn drive (4) awareness/knowledge, risk perception, preventive behaviors, and other emergency preparedness behaviors [

29]. For this segmentation analysis, we applied the framework working from the endpoints (PHEP outcomes) backwards to understand the link between audience segments and key theoretical drivers of outcomes of interest.

Utilizing the SIM as a theoretical framework, we developed three research questions for this study. First, what are the key audience segments among individuals who did not receive H1N1 vaccination based on key PHEP outcomes (awareness/knowledge, risk perception, and preventive behaviors)? Second, were there significant differences between audience segments in communication outcomes (information access, use, and exposure; information-seeking; and trust/credibility)? Third, were there significant differences between audience segments in social determinants (SEP, race/ethnicity, immigrant/nativity status, and place)?

2. Results

We drew from a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States, with oversampling of minority ethnic/racial groups and those living under the United States Federal Poverty Level (

n = 1569, response rate = 66/3%). Details regarding the full sample can be found elsewhere [

21]. We restricted the analysis to individuals who had not received the H1N1 vaccine and had complete data for the clustering variables (

n = 1166). As described in the Materials and Methods section in greater detail, we conducted a cluster analysis using as input variables the “PHEP outcomes” section of the theoretical framework: knowledge of H1N1, risk perception, vaccine safety, protective behavior against H1N1, and seasonal flu vaccine receipt.

The demographic profile of the sample is presented in

Table 1. The 1166 individuals ranged in age from 18 to 94 years, with an average of 44 years. About 44% had annual incomes below 100% of the United States Federal Poverty Level. About half of the sample had education levels of high school degree or less. The sample included 41% individuals who identified as White, non-Hispanic, 44% as Hispanic, and almost 10% as African-American, non-Hispanic.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of sample (n = 1166).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of sample (n = 1166).

| Characteristics | Number | Percent |

|---|

| Poverty level | | |

| Below 100% | 514 | 44.1 |

| Age (years) | | |

| 18–24 | 120 | 10.3 |

| 25–34 | 261 | 22.4 |

| 35–44 | 251 | 21.5 |

| 45–54 | 231 | 19.8 |

| 55–64 | 175 | 15.0 |

| 65–74 | 103 | 8.8 |

| 75+ | 25 | 2.1 |

| Income | | |

| Less than $20,000 | 484 | 41.5 |

| $20,000–$34,999 | 187 | 16.0 |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 140 | 12.0 |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 159 | 13.6 |

| $75,000 or more | 196 | 16.8 |

| Highest level of education completed | | |

| Less than high school | 242 | 20.8 |

| High school | 362 | 31.1 |

| Some college | 353 | 30.3 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 209 | 17.9 |

| Race/Ethnicity | | |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 483 | 41.4 |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 112 | 9.6 |

| Other, Non-Hispanic | 31 | 2.7 |

| Hispanic | 509 | 43.7 |

| 2+ Races, Non-Hispanic | 31 | 2.7 |

| Citizenship | | |

| Born in the United States | 818 | 70.2 |

| Gender | | |

| Female | 653 | 56.0 |

| Employment status | | |

| Working as a paid employee | 469 | 40.2 |

| Self-employed | 91 | 7.8 |

| On temporary layoff | 22 | 1.9 |

| Unemployed, but looking | 162 | 13.9 |

| Retired | 124 | 10.6 |

| Not working—disabled | 145 | 12.4 |

| Not working—other | 153 | 13.1 |

| Language spoken at home | | |

| English | 829 | 72.00 |

| Spanish | 311 | 27 |

| Other | 12 | 1.0 |

2.1. Assessing the Clustering Solution

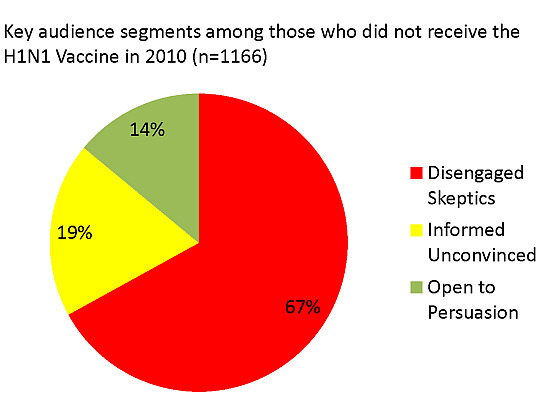

We determined that there were three distinct clusters, with 777, 226, and 163 members, respectively. The

R2 for this solution was 0.28. The first step in assessing the clustering solution was to look at the distribution of clustering variables (here, PHEP outcomes) between the three groups. As seen in

Table 2, there were important differences between the groups, reflected in their names. The “Disengaged Skeptics” cluster contained 777 individuals, or 67% of the sample. The “Informed Unconvinced” cluster contained 226 individuals (19% of the sample). The “Open to Persuasion” cluster contained 163 individuals (14% of the sample). These names reflect attitudes towards the H1N1 vaccination. Intention to receive the H1N1 vaccination varied greatly across groups. Approximately 10% of the Disengaged Skeptics, 21% of the Informed Unconvinced, and 37% of the Open to Persuasion reported intention to get the vaccine. Post-hoc comparisons provide additional details. Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Informed Unconvinced cluster had greater odds of reporting that they will get the vaccine, but haven’t tried yet (OR = 2.447, 95% CI: 1.503–3.984), higher odds of reporting that they tried, but it wasn’t available (OR = 4.495, 95% CI: 2.320–8.708), and higher odds of reporting that they don’t know (OR = 1.765, 95% CI: 1.249–2.494)

vs. reporting that they will not get the H1N1 vaccine. Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Open to Persuasion cluster had greater odds of reporting that they will get the vaccine, but haven’t tried yet (OR = 6.272, 95% CI: 3.881–10.135), higher odds of reporting that they have tried, but it wasn’t available (OR = 7.361, 95% CI: 3.654–14.381), and higher odds of reporting that they don’t know (OR = 1.966, 95% CI: 1.279–3.022)

vs. reporting that they will not get the H1N1 vaccine.

Table 2.

Distribution of PHEP outcomes between the cluster groups (n = 1166).

Table 2.

Distribution of PHEP outcomes between the cluster groups (n = 1166).

| PHEP Outcomes | Disengaged Skeptics (n = 777) (%) | Informed Unconvinced Cluster (n = 226) (%) | Open to Persuasion Cluster (n = 163) (%) | p-value |

|---|

| Intention to get [the H1N1] vaccine? | | | | <0.0001 |

| Will get the vaccine but have not tried yet | 7.5 | 13.3 | 26.3 | |

| Have tried to get the vaccine but it has not been available | 2.6 | 8.4 | 10.6 | |

| Will not get the vaccine | 66.0 | 47.8 | 36.9 | |

| Don’t know | 23.9 | 30.5 | 26.3 | |

| Seasonal flu vaccination status | | | | <0.0001 |

| Received | 0.3 | 100 | 30.1 | |

| Intention to receive seasonal flu vaccine among those who have not received it (n = 889) | | | | <0.0001 |

| Will get the vaccine but have not tried yet/Have tried to get the vaccine but it has not been available | 10.5 | n/a | 33.3 | |

| Will not get the vaccine | 67.2 | n/a | 44.7 | |

| Don’t know | 22.3 | n/a | 21.9 | |

| Correct answers: knowledge regarding transmission | | | | 0.3570 |

| 0 | 10.9 | 9.7 | 8.0 | |

| 1 | 47.8 | 50.9 | 43.6 | |

| 2 | 41.3 | 39.4 | 48.5 | |

| Correct answers: knowledge regarding symptoms | | | | 0.0054 |

| 0 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 1.8 | |

| 1 | 12.1 | 6.2 | 6.8 | |

| 2 | 19.7 | 19.0 | 14.7 | |

| 3 | 65.4 | 74.3 | 76.7 | |

| Risk perception: Likelihood of getting sick from H1N1 in the next 12 months, scale from 0 (not at all likely) to 10 (very likely) * | | | | 0.0113 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (2.3) | 3.3 (1.9) | 3.9 (2.4) | |

| Perceived safety of vaccine for influenza H1N1 for most people, scale from 0 (not at all safe) to 10 (very safe) * | | | | 0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.5 (2.4) | 6.2 (2.1) | 6.0 (2.5) | |

| Engagement in correct preventive behaviors | | | | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 100 | 100 | 0 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 92.0 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 8.0 | |

There were dramatic differences in seasonal flu vaccine receipt between the three groups. All individuals in the Informed Unconvinced group had received the seasonal flu vaccine versus 30% of the Open to Persuasion group and 0.3% of the Disengaged Skeptics group. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.0001). The groups did not differ significantly in knowledge about H1N1 transmission, but did vary in terms of knowledge regarding symptoms, risk perception, and perception of vaccine safety.

2.2. Uncertainty about Intention to Receive the H1N1 Vaccine

We explored the reasons behind reports that respondents “will not or do not know” if they will get the H1N1 vaccine. As seen in

Table 3, a range of 15 potential reasons was presented to respondents. For the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the top reason was not perceiving a risk of getting a serious case of influenza H1N1 (19%), followed by not being in a priority group to receive the vaccine (15%), and concern about side effects (13%). For the Informed Unconvinced cluster, the top reason was not being in a priority group to receive the vaccine (27%), followed by not perceiving a risk of getting a serious case of influenza H1N1 (17%), and followed by concern about side effects (12%). For the Open to Persuasion Cluster, the top reason was concern about side effects (26%), a lack of trust in public health officials to provide correct safety information for the vaccine (14%), and concern about getting influenza H1N1 from the vaccine (10%).

Table 3.

Distribution (%) of main reason for responding they “will not or do not know” if they will get the H1N1 vaccine (n = 954).

Table 3.

Distribution (%) of main reason for responding they “will not or do not know” if they will get the H1N1 vaccine (n = 954).

| Reasons | Disengaged Skeptics Cluster Subset (n = 678) | Informed Unconvinced Cluster Subset (n = 175) | Open to Persuasion Cluster subset (n = 101) | p-value |

|---|

| | | | | <0.0001 |

| You are not in one of the priority groups to receive the vaccine | 15.2 | 27.4 | 8.9 | |

| You have tried to get the vaccine, but it has not been available, and you will not try again | 1.6 | 4.6 | 1.0 | |

| You don’t think you are at risk of getting a serious case of influenza H1N1 | 19.2 | 16.6 | 8.9 | |

| You don’t think the vaccine would be effective in preventing you from getting influenza H1N1 | 7.4 | 2.9 | 5.9 | |

| You are concerned about getting influenza H1N1 from the vaccine | 5.6 | 4.0 | 9.9 | |

| You are concerned about getting another serious illness from the vaccine | 4.9 | 4.6 | 2.00 | |

| You are concerned about getting other kinds of side effects from the vaccine | 13.4 | 12.0 | 25.7 | |

| It would be too expensive for you to get the vaccine | 2.8 | 5.7 | 5.9 | |

| You don’t like shots or injections | 0.7 | 0 | 2.0 | |

| It will be too hard to get to a place where you could get the vaccine | 7.8 | 2.9 | 4.0 | |

| If you get influenza H1N1, you can get medication to treat it | 2.4 | 0 | 2.0 | |

| Your healthcare provider has told you that you shouldn’t get the vaccine | 1.3 | 4.6 | 3.0 | |

| You have been vaccinated for the seasonal flu and you believe this vaccine will also prevent you from getting H1N1 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 3.0 | |

| You don’t trust public health officials to provide correct information about the safety of the vaccine | 11.4 | 10.3 | 13.9 | |

| You do not know where to get the H1N1 vaccine | 6.2 | 2.9 | 4.0 | |

2.3. Communication Outcomes

Communication outcomes are key in the theoretical framework. As seen in

Table 4, there were important differences in media use. Overall, there were significant differences between clusters in use of newspapers, national TV news, and local TV news. The Informed Unconvinced cluster had the highest reports of use across these categories. When asked about the source from which the most information was received about the H1N1 outbreak, all three clusters reported local television news as the top source, followed by national network television news. Further post-hoc comparisons highlighted a few significant differences. Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Informed Unconvinced cluster reported higher odds of reporting primary H1N1 sources of national network television news (OR = 1.978, 95% CI: 1.339–2.921) and doctor, nurse, or other medical professional (OR = 1.740, 95% CI: 1.018–2.976)

vs. local television news. Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Open to Persuasion cluster had higher odds of reporting a primary H1N1 source of national network television news (OR = 1.642, 95% CI: 1.033–2.610)

vs. local television news. The three clusters had significant differences in trust in their primary H1N1 information source, attention to news on the H1N1 outbreak, and Internet access.

Table 4.

Information access, use, and trust, by cluster (n = 1166).

Table 4.

Information access, use, and trust, by cluster (n = 1166).

| Characteristics | Disengaged Skeptics Cluster (n = 777) (%) | Informed Unconvinced Cluster (n = 226) (%) | Open to Persuasion Cluster (n = 163) (%) | p-value |

|---|

| Number of days in past week… (mean, SD) * | | | | |

| Read a newspaper | 1.5 (2.4) | 2.5 (2.7) | 1.5 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

| Watched the national news on television | 2.8 (2.7) | 3.9 (2.8) | 3.8 (2.8) | <0.0001 |

| Watched the local news on television | 3.4 (2.7) | 4.7 (2.5) | 4.4 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Read news on the Internet | 1.9 (2.6) | 2.0 (2.6) | 1.7 (2.4) | 0.4396 |

| Source from which most information was received about the H1N1 outbreak | | | | 0.0013 |

| Local television news | 43.3 | 36.9 | 36.2 | |

| National network television news | 16.1 | 27.1 | 22.1 | |

| Cable network television news station | 4.3 | 2.7 | 6.8 | |

| Non-English speaking television station | 3.0 | 1.8 | 3.7 | |

| National newspaper | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | |

| Local newspaper | 4.8 | 6.7 | 1.2 | |

| Radio | 5.5 | 4.9 | 4.3 | |

| Internet | 9.7 | 6.7 | 6.8 | |

| Family member or friend | 5.6 | 2.2 | 4.3 | |

| Doctor, nurse or other medical professional | 7.2 | 10.7 | 14.1 | |

| Trust in source from which most H1N1 information was received | | | | 0.0011 |

| Reported trust | 53.2 | 64.2 | 65.0 | |

| Level of attention paid to the news on H1N1 outbreak, scale of 0 (no attention) to 10 (a lot of attention) * | | | | <0.0001 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.7 (2.5) | 6.2 (2.1) | 7.4 (2.5) | |

| Access to the Internet | 58.9 | 62.4 | 37.4 | <0.0001 |

| Have a social networking profile | | | | 0.0234 |

| Yes | 42.8 | 42.2 | 31.3 | |

2.5. Social Determinants

The final phase of inquiry focused on the link between social determinants and cluster membership. As seen in

Table 5, there were a few important differences between the clusters. The groups differed significantly by income level (

p < 0.01). The median income group for the Disengaged Skeptics cluster was $20,000–$34,999, $35,000–$49,999 for the Informed Unconvinced Cluster, and less than $20,000 for the Open to Persuasion Cluster. Post-hoc comparisons reveal that compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Informed Unconvinced cluster had greater odds of reporting the highest income bracket (OR = 1.524, 95% CI: 1.015–2.288)

vs. the lowest income bracket. Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Open to Persuasion cluster had lower odds of reporting the highest income bracket (OR = 0.236, 95% CI: 0.115–0.482)

vs. the lowest income bracket. The three clusters had significantly different racial/ethnic profiles (

p = 0.0003). Over half (57%) of the Open to Persuasion Cluster were Hispanic and over one-quarter (28%) were White, Non-Hispanic. Within the Informed Unconvinced Cluster, over half (53%) were White, Non-Hispanic, and about one-third (33%) were Hispanic. The Disengaged Skeptics cluster had 41% of its members identifying as White, Non-Hispanic and 44% as Hispanic. Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Informed Unconvinced cluster had lower odds of identifying as Hispanic (OR = 0.590, 95% CI: 0.425, 0.817)

vs. White, non-Hispanic. Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Open to Persuasion cluster had greater odds of identifying as Other, non-Hispanic (OR = 2.612, 95% CI: 1.040–6.561) and greater odds of identifying as Hispanic (OR = 1.933, 95% CI: 1.313–2.848)

vs. White, non-Hispanic. In terms of language spoken at home, the Open to Persuasion cluster had the highest proportion of members reporting Spanish as the predominant language (48%)

versus 14% of the Informed Unconvinced and 27% of the Disengaged Skeptics clusters. The difference was statistically significant (

p < 0.01).

Table 5.

Pattern of social determinants between three cluster groups (n = 1166).

Table 5.

Pattern of social determinants between three cluster groups (n = 1166).

| Social Determinants | Disengaged Skeptics Cluster (n = 777) (%) | Informed Unconvinced Cluster (n = 226) (%) | Open to Persuasion Cluster (n = 163) (%) | p-value |

|---|

| Income ($) | | | | 0.0003 |

| Less than 20,000 | 40.8 | 34.5 | 54.6 | |

| 20,000–34,999 | 16.9 | 14.2 | 14.7 | |

| 35,000–49,999 | 11.5 | 14.2 | 11.7 | |

| 50,000–74,999 | 13.4 | 14.6 | 13.5 | |

| 75,000 + | 17.5 | 22.6 | 5.5 | |

| Highest level of education completed | | | | 0.1899 |

| Less than high school | 20.9 | 17.3 | 25.2 | |

| High school | 30.2 | 30.1 | 36.2 | |

| Some college | 30.9 | 32.3 | 24.5 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 18.0 | 20.4 | 14.1 | |

| Race/ethnicity | | | | 0.0003 |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 41.1 | 52.7 | 27.6 | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 10.0 | 9.3 | 8.0 | |

| Other, Non-Hispanic | 2.5 | 2.2 | 4.3 | |

| Hispanic | 43.9 | 33.2 | 57.1 | |

| 2+ Races, Non-Hispanic | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.1 | |

| Born in the United States | | | | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 69.5 | 85.4 | 52.2 | |

| Language usually spoken at home | | | | <0.0001 |

| English | 72.3 | 86.0 | 51.2 | |

| Spanish | 26.6 | 13.5 | 47.5 | |

| Other | 1.2 | 0.5 | 1.2 | |

| Gender | | | | 0.0022 |

| Female | 52.4 | 63.7 | 62.6 | |

| Work status | | | | <0.0001 |

| Working as a paid employee | 43.2 | 37.6 | 29.5 | |

| Self-employed | 9.0 | 5.3 | 5.5 | |

| On temporary layoff | 2.3 | 0.4 | 1.8 | |

| Unemployed, but looking | 15.4 | 8.9 | 13.5 | |

| Retired | 6.2 | 25.7 | 11.0 | |

| Not working—disabled | 10.3 | 13.7 | 20.9 | |

| Not working—other | 13.5 | 8.4 | 17.8 | |

| Age group (years) | | | | <0.0001 |

| 18–24 | 12.7 | 4.9 | 6.1 | |

| 25–34 | 24.7 | 14.6 | 22.1 | |

| 35–44 | 22.3 | 16.4 | 25.2 | |

| 45–54 | 21.4 | 17.7 | 15.3 | |

| 55–64 | 13.1 | 20.4 | 16.6 | |

| 65–74 | 5.0 | 18.6 | 13.5 | |

| 75+ | 0.8 | 7.5 | 1.2 | |

| Marital status | | | | 0.0107 |

| Married | 42.9 | 50.4 | 50.3 | |

| Widowed | 3.1 | 6.7 | 3.7 | |

| Divorced | 9.8 | 11.1 | 11.0 | |

| Separated | 4.3 | 5.3 | 5.5 | |

| Never married | 28.2 | 17.7 | 17.8 | |

| Living with partner | 11.8 | 8.9 | 11.7 | |

The Informed Unconvinced cluster had the highest percentage of individuals born in the United States, with significant differences between groups.

Table 5 highlights the patterning of employment status between clusters. Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Informed Unconvinced cluster had greater odds of reporting being retired (OR = 4.778, 95% CI: 3.045–7.497). Compared to the Disengaged Skeptics cluster, the Open to Persuasion cluster had greater odds of reporting being retired (OR = 2.625, 95% CI: 1.412–4.882), not working—disabled (OR = 2.975, 95% CI: 1.800–4.917), and not working—other (OR = 1.933, 95% CI: 1.160–3.221). The age distribution across cohorts was significantly different (

p < 0.0001), with the Disengaged Skeptics cluster including more young people and the Informed Unconvinced cluster including many older adults.

2.6. Summary of the Three Clusters

The largest cluster was the Disengaged Skeptics cluster. Only about 10% of members indicated an intention to get the H1N1 vaccine. The group reported low uptake of/intention to receive the seasonal flu vaccine as well. The Disengaged Skeptics cluster reported low risk perception related to H1N1 and relatively lower perceptions of H1N1 vaccine safety. Key barriers to H1N1 vaccination included low risk perception, concern about side effects, and a lack of trust in public health officials. In terms of their information environment, this group had somewhat lower trust in their primary source of H1N1 information, lower attention to H1N1 news, and less information-seeking related to H1N1 than the other clusters. This group relied more heavily on local television news than the other groups. From a demographics standpoint, this group included more of the young respondents, included large numbers of White, non-Hispanics and Hispanics, had a lower percentage of women, and had the highest percentages of working adults compared to the other clusters.

In contrast, the Informed Unconvinced cluster was characterized by 21% indicating intention to receive the H1N1 vaccine, despite the fact that all of the individuals in this group reported receipt of the seasonal flu vaccine. As a group, they were relatively moderate in assessing risk of contracting H1N1 and vaccine safety. In addition to local and national network news, they relied on healthcare professionals as primary sources of H1N1 information. Overall, this group reported the highest media use overall, as well as Internet access. Also, among those who did not know or would not get the H1N1 vaccine, the top reason for not getting the vaccine in this cluster was not being part of a priority group. This group had the highest income levels, the largest proportion of White-non-Hispanic individuals, the highest proportion of US-born individuals, and the highest proportion of women. A large portion of the group was retired or not working for other reasons. They tended to be older as well.

The Open to Persuasion cluster was characterized by relative openness to the H1N1 vaccine; interestingly, less than one-third of this group had received the seasonal flu vaccine. Among those who had not received it, almost half said they would not get the seasonal flu vaccine. This group had lower risk perception than the other groups and more moderate perceptions about vaccine safety. They engaged in a higher number of correct preventive behaviors than the other groups. They paid a great deal of attention to H1N1-related news and had much higher rates of information-seeking than the other clusters. In addition to local and national network news, they relied on healthcare professionals as primary sources of H1N1 information. Demographically, they tended to have lower income levels and greater proportions of Hispanics, individuals from homes in which Spanish was the primary language, and individuals born outside of the United States.

3. Discussion

This study demonstrates the potential of using audience segmentation techniques to identify subgroups of vaccine-hesitant individuals and plan for effective engagement. We identified three important subgroups of individuals who did not receive the H1N1 vaccine, the Open to Persuasion, Informed Unconvinced, and Disengaged Skeptics clusters. The Open to Persuasion cluster seemed to be the furthest along the continuum towards vaccine acceptance for H1N1. There may have been an important opportunity to address the needs of this group and increase vaccination rates. By providing details about the group’s current beliefs, behaviors, and communication profiles, the analysis is a useful starting point for targeted engagement. The Informed Unconvinced cluster appeared to be in the middle along the continuum and may have been relatively sophisticated consumers of health information. The issue may be that they were discriminating consumers of information and the information they received either did not satisfy them or did not prompt them to accept H1N1 vaccination. The communication strategies targeting such a group may need to address a high level of knowledge and potential skepticism related to this disease and vaccine specifically. Finally, the Disengaged Skeptics cluster appeared to be relatively far away from acceptance of the H1N1 vaccine. This group may have needed to be brought along slowly regarding more than just the H1N1 vaccine. The statistically significant differences between clusters on a number of key theoretical constructs in our framework support the validity of the groupings that emerged from this segmentation analysis. The dramatic differences between groups in seasonal influenza vaccination status are an example of a result that would prompt further inquiry to replicate or explain as part of the development of customized communication strategies. In line with the SIM, our findings highlight the critical roles played by communication and information in vaccination decisions, which can provide an opening to engaging with the diverse segments of the public along the vaccine hesitancy continuum for a given vaccine. Use of a health behavior or health communication theory to drive the segmentation analysis allows for effective targeting of key variables to promote behavior change [

27].

The results of this study highlight the potential to use this approach to develop communication strategies to target clusters of vaccine-hesitant individuals. As seen by Leask

et al.’s [

30] synthesis of studies related to parental vaccine hesitancy, the field will benefit from integration of multiple segmentation efforts. This will yield both estimates of group sizes as well as useful classification criteria. It may be particularly important to assess the size and characteristics of dissonant groups, which may be small, but have strong impact if their messages are amplified greatly by interpersonal channels, online and offline. At the same time, the literature includes a number of assessments linking vaccine uptake to clustering by social networks, geography, sociodemographic characteristics, and psychosocial characteristics [

13,

31,

32]. The addition of the social determinants and communication outcomes extends the ability of public health practitioners to segment the market more effectively.

Targeted strategies that account for different information consumption and source preference patterns are likely required. This is particularly important as the media environment becomes increasingly fragmented [

33] and individuals are less likely to encounter information that is contrary to the existing beliefs in their typical media platforms and interpersonal networks. Primary sources for information about new diseases/vaccines may differ widely in their ability to mitigate concerns about safety and encourage sufficient attention and concern [

19]. A recent surveillance study that assessed web-based information about vaccines found that over two-thirds (69%) of the content of articles, blogs, reports,

etc. were positive, but the remaining one-third of the content had a negative tone and emphasized beliefs that could have tremendous influence on the public [

34]. In addition to strategic methods of reaching diverse clusters of the vaccine-hesitant individuals, it is vital to ensure that communications focus on engagement and informed decision-making. It is increasingly clear that top-down, authoritative communication strategies do not support public health goals and an engaged approach, whether on the part of governments, healthcare professionals, or community organizations, can support open discussions and decision-making [

22].

Taking a social ecological perspective, we recognize that vaccination decisions are not made in a vacuum, but instead are influenced by (and influence) factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, political, and cultural levels [

35,

36]. This prompts attention to the ways in which individuals engage with information and interact with social groups and networks (online and offline), communities, institutions (particularly those in the healthcare sector as well as employers), policies (including prioritization of population groups), and cultural drivers. A segmentation analysis such as this can therefore play an important role in a broader assessment, such as the World Health Organization’s Tailoring Immunizations Program. This program guides member states in the conduct of multi-level assessments to promote vaccination by identifying vulnerable populations (using segmentation), assessing barriers to vaccination (both supply-side and demand-side), and creating effective responses [

37]. The segmentation variables presented here could serve as a complement to existing suggestions for segmentation analysis and further refine the ability to identify and engage with key subgroups. Once more, a theory-driven set of variables is useful as it supports a targeted selection of variables (both for identifying subgroups and also for creating response strategies).

The audience segmentation analysis demonstrated here may be useful in a range of settings. This assessment was conducted at the national level, but the approach could be applied at local or regional levels as well. Fielding the survey was both cost-effective and efficient with the use of an online panel. This mode of survey administration may not be appropriate if the panels do not sufficiently represent vulnerable populations. For this study, we addressed this challenge by oversampling key racial/ethnic minority groups and individuals living under the United States Federal Poverty Level. Regardless of mode of administration, this type of survey can be fielded in much the same way as any other quantitative survey and can be utilized in settings where that method is appropriate and feasible. The data analysis required is fairly straightforward, though it requires familiarity with cluster analysis. Despite the potential of the segmentation approach, an important challenge relates to the ability to conduct segmentation in real-time. While theories of behavior change provide a useful starting point, the time requirements of customizing the set of segmentation variables and behavioral antecedents for a given vaccine pose a challenge. Also, even in cases where automated approaches are appropriate and the survey can be administered quickly, time is needed to create intervention and communication strategies based on those data. There may be an opportunity to integrate rapid segmentation assessments with ongoing monitoring efforts, such as programs conducting ongoing surveillance of vaccine-related discussions on social media [

22]. A useful example of the application of this approach comes from the field of climate change. A group of scientists have segmented the American population into the “Six Americas” of climate change and have characterized the segments in terms of beliefs, concern, and engagement about climate change. They have also tracked the changes in the sizes of the segments over time and studied their policy and communication preferences. In this way, appropriately directed and tailored engagement strategies can be created for diverse subgroups [

38,

39].

As with any study, the results must be interpreted in the context of a set of limitations. First, the clustering solution presented only explains 28% of the variation in the model. This is a function of our decision to focus on PHEP outcomes to segment the population. The benefit of our approach is that the resulting behavior-driven clusters can then be tied back to potential communication leverage points to support behavior change. In addition to the areas typically focused on (sociodemographic factors, geographic variation, etc.), understanding groups’ channel preferences, trusted sources, and other communication-related details allows for much more sophisticated engagement and provision of information. Second, we did not assess three of the components of the model (social networks, information processing, and place) in this study, which should be added in future work. Third, the timing of the survey (March 2010, as the 2009–2010 influenza season was winding down) impacts the questions regarding intention to receive the H1N1 vaccine, so we interpreted them in the context of responses regarding attempts to receive the H1N1 vaccine, reasons for being unsure about H1N1 vaccination, and seasonal influenza vaccine receipt. The strengths of the study outweigh these limitations. The use of a theory-driven strategy for segmentation provides insight into communication/engagement leverage points that may be particularly useful in the context of vaccines with which the public is unfamiliar. The guidance from the SIM model prompted inclusion of key segmenting variables, while maintaining parsimony. Another strength of the study is the use of cluster analysis without a priori specification of the number of clusters. This data-driven approach allowed for cluster patterns to emerge systematically from the data.

Further research efforts to use this approach to inform targeted public engagement strategies may unearth additional sub-groupings among the vaccine-hesitant. Additional segmentation studies focused on a range of vaccines will also allow for deeper understanding of the common and vaccine-specific aspects of hesitancy. By better understanding the spectrum of vaccine-hesitancy, we can begin to put into place the necessary supports to inform and support health-promotive decision-making among the public.