A Scoping Review of Influences on HPV Vaccine Uptake in the Rural US †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

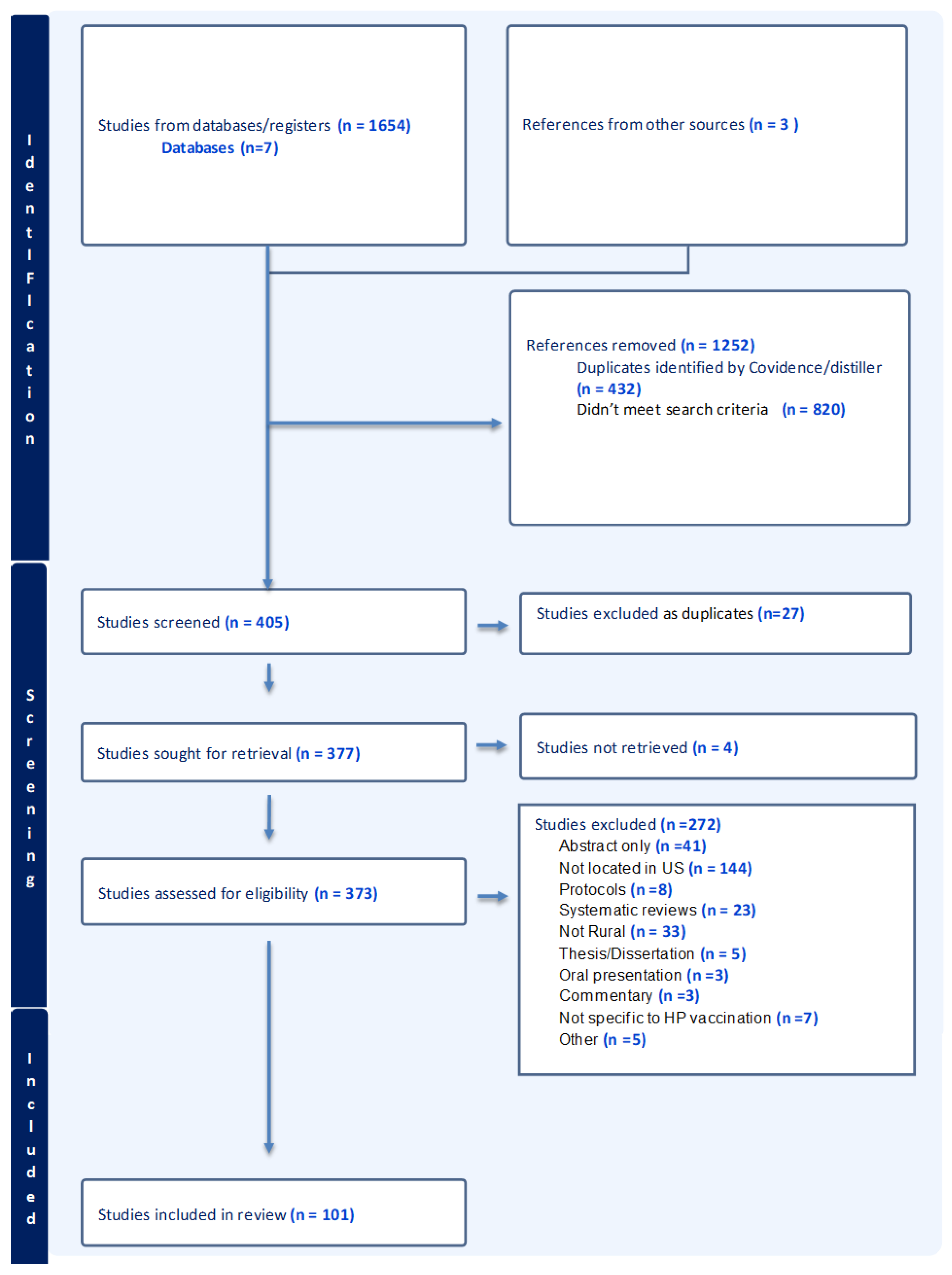

2.2. Source of Evidence Screening and Selection

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Descriptions

3.2. The Characteristics of HPV Vaccine Interventions

3.3. Theoretical Models

3.4. Multilevel Interventions and Change

3.5. HPV Vaccination Outcomes of Initiation, Completion, or Both

3.6. Predictors of HPV Vaccine Initiation

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Results

4.2. Sociodemographic Influences

4.3. Healthcare Provider Influences

4.4. Multilevel Observations and Interventions

4.5. Theory as a Guide

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Search Strategy

Appendix A.1.1. Medline

- exp Papillomavirus Infections/or exp Alphapapillomavirus/or (“papillomavirus infection*” or “Human Papillomavirus” or “Human papilloma virus” or HPV).tw,kw.

- Exp immunization/or exp Immunization programs/or exp Papillomavirus Vaccines/or Vaccines/or (vaccin* OR immuniz* OR immunis* OR inoculat* OR Nine-valent OR “nine valent” OR bivalent OR quadrivalent OR Gardasil OR cervarix).tw,kw.

- Exp patient acceptance of health care/OR exp Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice/OR vaccination refusal/OR anti-vaccination movement/OR exp decision making/OR trust/OR exp risk assessment OR exp religion/OR (accept* OR aware* OR attitude* OR knowledge OR belief* OR view* OR opinion* OR barrier* OR support* OR behave*OR decision OR decide OR intent* OR undecided OR hesita* OR doubt* OR refus* OR reject* OR omission* OR omit* OR object OR objection OR incomplet* OR delay* OR suboptimal* OR intent* OR know* OR perceive* OR percept* OR perspective* OR understand* OR prefer* OR risk* OR uptake* OR will* OR hesitan* OR reluctan* OR fear OR concern* OR trust OR uncertain* or distrust OR anti-vax* OR anti-vacc* OR antivax* or antivaccin* OR wary OR religion OR religious).tw,kw.

- Exp rural health services/OR rural population/OR rural health/OR “Hospitals, Rural”/OR Medically Underserved Area/OR exp population dynamics/OR exp residence characteristics/OR (remote OR rural OR Appalachia OR (regional adj3 disparit*) OR “small town*” OR (region* adj3 disparities) OR ((geographic* OR medical*) adj3 (underserv* OR underrepresent*)) OR (underserv* adj3 (population* OR communit* OR area*)) OR (shortage adj3 area)).tw,kw.

- (1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4)

Appendix A.1.2. Embase

- ‘Papillomavirus Infection’/exp OR ‘Alphapapillomavirus’/exp OR (“Human Papillomavirus” OR “papillomavirus infection*” OR “Human papilloma virus” OR HPV): ti, ab, kw

- ‘immunization’/exp OR ‘wart virus Vaccine’/de OR ‘Vaccine’/de OR (vaccin* OR immuniz* OR immunis* OR inoculat* OR Nine-valent OR “nine valent” OR bivalent OR quadrivalent OR Gardasil OR cervarix): ti, ab, kw

- ‘Patient attitude’/exp OR ‘attitude to health’/de OR ‘anti-vaccination movement’/de OR ‘patient decision making’/de OR ‘trust’/de OR ‘risk assessment’/de OR ‘religion’/exp OR (accept* OR aware* OR attitude* OR knowledge OR belief* OR view* OR opinion* OR barrier* OR support* OR behave* OR decision OR decide OR intent* OR undecided OR hesita* OR doubt* OR refus* OR reject* OR omission* OR omit* OR object OR objection OR incomplet* OR delay* OR suboptimal* OR intent* OR know* OR perceive* OR percept* OR perspective* OR understand* OR prefer* OR risk* OR uptake* OR will* OR hesitan* OR reluctan* OR fear OR concern* OR trust OR uncertain* OR distrust OR anti-vax* OR anti-vacc* OR antivax* OR antivaccin* OR wary OR religion OR religious): ti, ab, kw

- ‘rural health care’/exp OR ‘rural population’/de OR ‘rural health’/de OR ‘rural hospital’/de OR ‘Medically Underserved’/de OR ‘population dynamics’/exp OR ‘demography”/de OR (remote OR rural OR Appalachia OR (regional NEAR/3 disparit*) OR “small town*” OR (region* NEAR/3 disparities) OR ((geographic* OR medical*) NEAR/3 (underserv* OR underrepresent*)) OR (underserv* NEAR/3 (population* OR communit* OR area*)) OR (shortage NEAR/3 area)): ti, ab, kw

- #5:

- [06-07-2023]/sd

- #6:

- [embase]/lim NOT ([embase]/lim AND [medline]/lim)

- #7.

- (#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 AND #6)

Appendix A.1.3. CINAHL

- (MH “Papillomavirus Infections+”) OR (TI “papillomavirus infection*” OR AB “papillomavirus infection*”) OR (TI “Human Papillomavirus” OR AB “Human Papillomavirus”) OR (TI “Human papilloma virus” OR AB “Human papilloma virus”) OR (TI HPV OR AB HPV)

- (MH “immunization”) OR (MH “Papillomavirus Vaccines”) OR (MH “Viral Vaccines”) OR ((TI vaccin* OR AB vaccin*) OR (TI immuniz* OR AB immuniz*) OR (TI immunis* OR AB immunis*) OR (TI inoculat* OR AB inoculat*) OR (TI Nine-valent OR AB Nine-valent) OR (TI “nine valent” OR AB “nine valent”) OR (TI bivalent OR AB bivalent) OR (TI quadrivalent OR AB quadrivalent) OR (TI Gardasil OR AB Gardasil) OR (TI cervarix OR AB cervarix)

- (MH “Patient Attitudes”) OR (MH “Attitude to Vaccines”) OR (MH “Health Knowledge”) OR (MH “anti-vaccination movement”) OR (MH “decision making, patient”) OR (MH “trust”) OR (MH “risk assessment”) OR (MH “religion and relgions+”) OR ((TI accept* OR AB accept*) OR (TI aware* OR AB aware*) OR (TI attitude* OR AB attitude*) OR (TI knowledge OR AB knowledge) OR (TI belief* OR AB belief*) OR (TI view* OR AB view*) OR (TI opinion* OR AB opinion*) OR (TI barrier* OR AB barrier*) OR (TI support* OR AB support*) OR (TI behave* OR AB behave*) OR (TI decision OR AB decision) OR (TI decide OR AB decide) OR (TI intent* OR AB intent*) OR (TI undecided OR AB undecided) OR (TI hesita* OR AB hesita*) OR (TI doubt* OR AB doubt*) OR (TI refus* OR AB refus*) OR (TI reject* OR AB reject*) OR (TI omission* OR AB omission*) OR (TI omit* OR AB omit*) OR (TI object OR AB object) OR (TI objection OR AB objection) OR (TI incomplet* OR AB incomplet*) OR (TI delay* OR AB delay*) OR (TI suboptimal* OR AB suboptimal*) OR (TI intent* OR AB intent*) OR (TI know* OR AB know*) OR (TI perceive* OR AB perceive*) OR (TI percept* OR AB percept*) OR (TI perspective* OR AB perspective*) OR (TI understand* OR AB understand*) OR (TI prefer* OR AB prefer*) OR (TI risk* OR AB risk*) OR (TI uptake* OR AB uptake*) OR (TI will* OR AB will*) OR (TI hesitan* OR AB hesitan*) OR (TI reluctan* OR AB reluctan*) OR (TI fear OR AB fear) OR (TI concern* OR AB concern*) OR (TI trust OR AB trust) OR (TI uncertain* OR AB uncertain*) OR (TI distrust OR AB distrust) OR (TI anti-vax* OR AB anti-vax*) OR (TI anti-vacc* OR AB anti-vacc*) OR (TI antivax* OR AB antivax*) OR (TI antivaccin* OR AB antivaccin*) OR (TI wary OR AB wary) OR (TI religion OR AB religion) OR (TI religious OR AB religious)

- (MH “rural health services”) OR (MH “rural population”) OR (MH “rural health”) OR (MH “Hospitals, Rural”) OR (MH “Medically Underserved Area”) OR (MH “population characteristics”) OR (MH “residence characteristics”) OR ((TI remote OR AB remote) OR (TI rural OR AB rural) OR (TI Appalachia OR AB Appalachia) OR ((TI regional OR AB regional) N3 (TI disparit* OR AB disparit*)) OR (TI “small town*” OR AB “small town*”) OR ((TI region* OR AB region*) N3 (TI disparities OR AB disparities)) OR (((TI geographic* OR AB geographic*) OR (TI medical* OR AB medical*)) N3 ((TI underserv* OR AB underserv*) OR (TI underrepresent* OR AB underrepresent*))) OR ((TI underserv* OR AB underserv*) N3 ((TI population* OR AB population*) OR (TI communit* OR AB communit*) OR (TI area* OR AB area*))) OR ((TI shortage OR AB shortage) N3 (TI area OR AB area)))

- #5:

- (1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 AND 5)

Appendix A.1.4. Scopus

- TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Papillomavirus Infection*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“papillomavirus infection*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Alphapapillomavirus”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Human Papillomavirus”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Human papilloma virus”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“HPV”)

- TITLE-ABS-KEY (“immunization”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Vaccin*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“immuniz*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“immunis*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“inoculat*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Nine-valent”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“nine valent”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“bivalent”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“quadrivalent”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Gardasil”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“cervarix”)

- INDEXTERMS (“patient acceptance of health care”) OR INDEXTERMS (“Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice”) OR INDEXTERMS (“anti-vaccination movement”) OR INDEXTERMS (“decision making”) OR INDEXTERMS (“trust”) OR INDEXTERMS (“risk assessment”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“accept*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“aware*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“attitude*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“knowledge”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“belief*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“view*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“opinion*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“barrier*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“support*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“behave*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“decision”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“decide”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“intent*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“undecided”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“hesita*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“doubt*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“refus*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“reject*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“omission*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“omit*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“object”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“objection”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“incomplet*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“delay*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“suboptimal*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“intent*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“know*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“perceive*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“percept*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“perspective*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“understand*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“prefer*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“risk*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“uptake*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“will*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“hesitan*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“reluctan*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“fear”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“concern*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“trust”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“uncertain*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“distrust”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“anti-vax*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“anti-vacc*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“antivax*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“antivaccin*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“wary”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“religion”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“religious”)

- INDEXTERMS (“Medically Underserved Area”) OR INDEXTERMS (“population dynamics”) OR “exp residence characteristics” OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“remote”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“rural”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Appalachia”) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“regional”) W/3 TITLE-ABS-KEY (“disparit*”)) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“small town*”) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“region*”) W/3 TITLE-ABS-KEY (“disparities”)) OR ( (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“geographic*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“medical*”)) W/3 (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“underserv*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“underrepresent*”))) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“underserv*”) W/3 (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“population*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“communit*”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“area*”))) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“shortage”) W/3 TITLE-ABS-KEY (“area”)))

- #5:

- ORIG-LOAD-DATE AFT 20230706

- #5

- (#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5)

Appendix A.1.5. PsycInfo

- (DE “Human Papillomavirus”) OR ((TI “Human Papillomavirus” OR AB “Human Papillomavirus”) OR (TI “papillomavirus infection*” OR AB “papillomavirus infection*”) OR (TI “Human papilloma virus” OR AB “Human papilloma virus”) OR (TI HPV OR AB HPV))

- (DE “immunization”) OR ((TI vaccin* OR AB vaccin*) OR (TI immuniz* OR AB immuniz*) OR (TI immunis* OR AB immunis*) OR (TI inoculat* OR AB inoculat*) OR (TI Nine-valent OR AB Nine-valent) OR (TI “nine valent” OR AB “nine valent”) OR (TI bivalent OR AB bivalent) OR (TI quadrivalent OR AB quadrivalent) OR (TI Gardasil OR AB Gardasil) OR (TI cervarix OR AB cervarix))

- (DE “Health Knowledge”) OR (DE “decision making”) OR (DE “trust”) OR (DE “risk assessment”) OR (DE “religion+”) OR ((TI accept* OR AB accept*) OR (TI aware* OR AB aware*) OR (TI attitude* OR AB attitude*) OR (TI knowledge OR AB knowledge) OR (TI belief* OR AB belief*) OR (TI view* OR AB view*) OR (TI opinion* OR AB opinion*) OR (TI barrier* OR AB barrier*) OR (TI support* OR AB support*) OR (TI behave* OR AB behave*) OR (TI decision OR AB decision) OR (TI decide OR AB decide) OR (TI intent* OR AB intent*) OR (TI undecided OR AB undecided) OR (TI hesita* OR AB hesita*) OR (TI doubt* OR AB doubt*) OR (TI refus* OR AB refus*) OR (TI reject* OR AB reject*) OR (TI omission* OR AB omission*) OR (TI omit* OR AB omit*) OR (TI object OR AB object) OR (TI objection OR AB objection) OR (TI incomplet* OR AB incomplet*) OR (TI delay* OR AB delay*) OR (TI suboptimal* OR AB suboptimal*) OR (TI intent* OR AB intent*) OR (TI know* OR AB know*) OR (TI perceive* OR AB perceive*) OR (TI percept* OR AB percept*) OR (TI perspective* OR AB perspective*) OR (TI understand* OR AB understand*) OR (TI prefer* OR AB prefer*) OR (TI risk* OR AB risk*) OR (TI uptake* OR AB uptake*) OR (TI will* OR AB will*) OR (TI hesitan* OR AB hesitan*) OR (TI reluctan* OR AB reluctan*) OR (TI fear OR AB fear) OR (TI concern* OR AB concern*) OR (TI trust OR AB trust) OR (TI uncertain* OR AB uncertain*) OR (TI distrust OR AB distrust) OR (TI anti-vax* OR AB anti-vax*) OR (TI anti-vacc* OR AB anti-vacc*) OR (TI antivax* OR AB antivax*) OR (TI antivaccin* OR AB antivaccin*) OR (TI wary OR AB wary) OR (TI religion OR AB religion) OR (TI religious OR AB religious))

- (DE “rural environments”) OR (DE “rural health”) OR ((TI remote OR AB remote) OR (TI rural OR AB rural) OR (TI Appalachia OR AB Appalachia) OR ((TI regional OR AB regional) N3 (TI disparit* OR AB disparit*)) OR (TI “small town*” OR AB “small town*”) OR ((TI region* OR AB region*) N3 (TI disparities OR AB disparities)) OR (((TI geographic* OR AB geographic*) OR (TI medical* OR AB medical*)) N3 ((TI underserv* OR AB underserv*) OR (TI underrepresent* OR AB underrepresent*))) OR ((TI underserv* OR AB underserv*) N3 ((TI population* OR AB population*) OR (TI communit* OR AB communit*) OR (TI area* OR AB area*))) OR ((TI shortage OR AB shortage) N3 (TI area OR AB area)))

- (#1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4)

Appendix A.1.6. Cochrane

- [mh “Papillomavirus Infections”] OR [mh Alphapapillomavirus] OR (“papillomavirus infection*” OR “Human Papillomavirus” OR “Human papilloma virus” OR HPV): ti, ab, kw.

- [mh immunization] OR [mh “Immunization programs”] OR [mh “Papillomavirus Vaccines”] OR [mh Vaccines] OR (vaccin* OR immuniz* OR immunis* OR inoculat* OR Nine-valent OR “nine valent” OR bivalent OR quadrivalent OR Gardasil OR cervarix): ti, ab, kw.

- [mh “patient acceptance of health care”] OR [mh “Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice”] OR [mh “vaccination refusal”] OR [mh “anti-vaccination movement”] OR [mh “decision making”] OR [mh trust] OR [mh “risk assessment OR exp religion”] OR (accept* OR aware* OR attitude* OR knowledge OR belief* OR view* OR opinion* OR barrier* OR support* OR behave* OR decision OR decide OR intent* OR undecided OR hesita* OR doubt* OR refus* OR reject* OR omission* OR omit* OR object OR objection OR incomplet* OR delay* OR suboptimal* OR intent* OR know* OR perceive* OR percept* OR perspective* OR understand* OR prefer* OR risk* OR uptake* OR will* OR hesitan* OR reluctan* OR fear OR concern* OR trust OR uncertain* OR distrust OR anti-vax* OR anti-vacc* OR antivax* OR antivaccin* OR wary OR religion OR religious): ti, ab, kw.

- [mh “rural health services”] OR [mh “rural population”] OR [mh “rural health”] OR [mh “Hospitals, Rural”] OR [mh “Medically Underserved Area”] OR [mh “population dynamics”] OR [mh “residence characteristics”] OR (remote OR rural OR Appalachia): ti, ab, kw. OR (regional NEAR/3 disparit*): ti, ab, kw. OR (“small” NEAR/2 town*): ti, ab, kw. OR (region* NEAR/3 disparities): ti, ab, kw. OR ((geographic* OR medical*) NEAR/3 (underserv* OR underrepresent*)): ti, ab, kw. OR (underserv* NEAR/3 (population* OR communit* OR area*)): ti, ab, kw. OR (shortage NEAR/3 area): ti, ab, kw.

Appendix A.1.7. Sociological Abstracts

- TI (“papillomavirus infection*” OR “Human Papillomavirus” or “Human papilloma virus” or HPV) OR AB (“papillomavirus infection*” OR “Human Papillomavirus” or “Human papilloma virus” or HPV)

- SU (“immunization”) OR SU (“vaccination”) or TI (vaccin* OR immuniz* OR immunis* OR inoculat* OR Nine-valent OR “nine valent” OR bivalent OR quadrivalent OR Gardasil OR cervarix) OR AB (vaccin* OR immuniz* OR immunis* OR inoculat* OR Nine-valent OR “nine valent” OR bivalent OR quadrivalent OR Gardasil OR cervarix)

- SU (“Health attitudes”) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT.EXPLODE (“Decision Making”) OR SU (“trust”) OR SU (“risk”) OR SU (“religions”) OR (TI (accept* OR aware* OR attitude* OR knowledge OR belief* OR view* OR opinion* OR barrier* OR support* OR behave* OR decision OR decide OR intent* OR undecided OR hesita* OR doubt* OR refus* OR reject* OR omission* OR omit* OR object OR objection OR incomplet* OR delay* OR suboptimal* OR intent* OR know* OR perceive* OR percept* OR perspective* OR understand* OR prefer* OR risk* OR uptake* OR will* OR hesitan* OR reluctan* OR fear OR concern* OR trust OR uncertain* or distrust OR anti-vax* OR anti-vacc* OR antivax* or antivaccin* OR wary OR religion OR religious) OR AB (accept* OR aware* OR attitude* OR knowledge OR belief* OR view* OR opinion* OR barrier* OR support* OR behave* OR decision OR decide OR intent* OR undecided OR hesita* OR doubt* OR refus* OR reject* OR omission* OR omit* OR object OR objection OR incomplet* OR delay* OR suboptimal* OR intent* OR know* OR perceive* OR percept* OR perspective* OR understand* OR prefer* OR risk* OR uptake* OR will* OR hesitan* OR reluctan* OR fear OR concern* OR trust OR uncertain* or distrust OR anti-vax* OR anti-vacc* OR antivax* or antivaccin* OR wary OR religion OR religious))

- SU (“Rural Population”) OR SU (“Rural Areas”) OR SU (“Rurality”) OR SU (“Rural Communities”) OR SU (“Rural Urban Differences”) OR SU (“residence”) OR TI (remote OR rural OR Appalachia OR (regional adj3 disparit*) OR “small town*” OR (region* adj3 disparities) OR ((geographic* OR medical*) adj3 (underserv* OR underrepresent*)) OR (underserv* adj3 (population* OR communit* OR area*)) OR (shortage adj3 area)) OR AB (remote OR rural OR Appalachia OR (regional adj3 disparit*) OR “small town*” OR (region* adj3 disparities) OR ((geographic* OR medical*) adj3 (underserv* OR underrepresent*)) OR (underserv* adj3 (population* OR communit* OR area*)) OR (shortage adj3 area))

- (1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4)

Appendix B. Full Study Characteristics (N = 101)

| Reference | Publication Year | Location | Study Years | Purpose/Aims | Study Type | Sample Size | Participant Type | Theory, Model, and Framework | Primary Outcomes Measured | Other Outcomes Measured | Primary Findings | Other Findings |

| Bhatta MP, Phillips L. Human papillomavirus vaccine awareness, uptake, and parental and healthcare provider communication among 11- to 18-year-old adolescents in a rural Appalachian Ohio county in the United States. J Rural Health Winter. 2015;31(1):67–75. doi:10.1111/jrh.12079 [26] | 2014 | Midwest | 2012 | Examine the levels of adolescent HPV vaccine awareness, uptake, and parental and healthcare provider communication; assess the relationship between the parental and healthcare provider communication regarding the HPV vaccine, and the vaccine uptake from the adolescent perspective | Cross-sectional survey | 1299 | Parents of adolescents | HPV vaccine initiation and awareness | Parental and provider communication about HPV vaccine | 49.2% of respondents reported that they have heard of the HPV vaccine. Overall, 19.4% of the adolescents indicated having a discussion with their parents about the HPV vaccine. Nearly a quarter (24.6%) of the adolescents indicated having a healthcare provider discuss the HPV vaccine with them. | Both parental and healthcare provider communication were significantly associated with HPV vaccine uptake in this population (p < 0.0001) | |

| Crosby RA, Casey BR, Vanderpool R, Collins T, Moore GR. Uptake of free HPV vaccination among young women: a comparison of rural versus urban rates. J Rural Health Winter. 2011;27(4):380–384. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00354.x [27] | 2011 | South | 2007–2009 | Compare rates of initial HPV vaccine uptake, offered at no cost, between a rural clinic, a rural community college, and an urban college clinic and to identify rural–urban differences in uptake of free booster doses | quasi-experimental study | 706 | Adults | HPV vaccine Initiation and Completion | The contrast in initial uptake between urban clinic women and rural college women was significant (p < 0.0001), but the difference in initial uptake between urban clinic women and rural clinic women was not significant (p = 0.42). Rural clinic women were about 7 times more likely than urban clinic women (p < 0.0001) to not return for at least 1 follow-up dose. The difference between urban clinic women and rural college women was significant for follow-up vaccine doses (p = 0.014). | |||

| * Osaghae I, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Shete S. Healthcare Provider Recommendations and Observed Changes in HPV Vaccination Acceptance during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines. 2022;10(9):1515. doi:10.3390/vaccines10091515 [36] | 2022 | South | 2021 | Examine the association between HPV vaccination recommendation by HCPs and their observed changes in HPV Vaccination acceptance during the COVID-19 pandemic | Cross-sectional study | 1283 | Providers | HPV vaccine initiation | 554 (77.5%) reported no change, 99 (13.9%) reported a decrease, and 62 (8.7%) reported an increase in HPV vaccination acceptance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Providers who recommended the vaccine often/always had 46% (OR = 0.54; 95%CI: 0.30–0.96) lower odds of reporting a decrease in HPV vaccination acceptance during the COVID-19 pandemic | |||

| Ryan G, Gilbert PA, Ashida S, Charlton ME, Scherer A, Askelson NM. Challenges to Adolescent HPV Vaccination and Implementation of Evidence-Based Interventions to Promote Vaccine Uptake During the COVID-19 Pandemic: “HPV Is Probably Not at the Top of Our List.” Prev Chronic Dis. 2022;19. doi:10.5888/pcd19.210378 [38] | 2022 | Midwest | 2020 | Assess how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted opportunities for HPV vaccination delivery and EBI implementation | Qualitative | 18 | Clinic Managers and administrators | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research | Clinic challenges to implementing HPV vaccines during COVID-19 pandemic | The pandemic led to an overall decrease in HPV vaccinations as well as routine care. Additionally, the pandemic disrupted EBI work (evidence-based interventions) | ||

| Adjei Boakye E, Fedorovich Y, White M, et al. Rural–Urban Disparities in HPV Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents in the Central Part of the State of Illinois, USA. J Community Health. 2022;48(1):24–29. doi:10.1007/s10900-022-01136-x [52] | 2022 | Midwest | 2015–2020 | Quantify the rates of HPV vaccine initiation and completion in an academic medical center in central Illinois and identify factors associated with both outcomes | Retrospective Chart Review | 9351 | Adolescents | HPV vaccine initiation and completion | Vaccine initiation for HPV was 46.2% and completion was 24.7% among the participants. Older age and being female increased the odds of initiating and completing the HPV vaccination. Adolescents residing in rural areas were 38% and 24% less likely to initiate (aOR = 0.62; 95 CI: 0.54–0.72) and complete (aOR = 0.76, 95 CI: 0.65–0.88) the HPV vaccine compared to those in urban areas. Adolescents were less likely to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine if they were not up-to-date on the hepatitis A, meningococcal, and TDaP vaccines. | |||

| Adjei Boakye E, McKinney SL, Whittington KD, et al. Association between Sexual Activity and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Initiation and Completion among College Students. Vaccines. 2022;10(12):2079. doi:10.3390/vaccines10122079 [53] | 2022 | Midwest | 2021 | Examine if sexual activity was associated with HPV vaccination uptake among university students | Cross-sectional study | 951 | Adults | HPV vaccine initiation and completion | Students who had ever engaged in sexual activity were more likely to have initiated (aOR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.34–3.17) the HPV vaccine; however, no difference was observed for HPV vaccine completion. | |||

| Askelson N, Ryan G, McRee AL, et al. Using concept mapping to identify opportunities for HPV vaccination efforts: Perspectives from the Midwest and West Coast. Eval Program Plann. 2021;89:102010. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2021.102010 [54] | 2021 | Midwest, West | 2018–2019 | Solicit perspectives on barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination from state-level stakeholders | Observational | 134 | Other (stakeholders) | Barriers and facilitators to HPV vaccination from state-level stakeholders | Clusters rated most feasible included coordinated/consistent messaging and education. Clusters rated as most important for improving vaccination in rural areas were education (Mean [M] = 4.21), provider influence (M = 4.10), and evidence-based interventions (M = 4.07). All items except coordinated/consistent messaging were rated as more important than feasible. | |||

| Askelson NM, Campo S, Lowe JB, Smith S, Dennis LK, Andsager J. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Mothers’ Intentions to Vaccinate Their Daughters Against HPV. J Sch Nurs. 2010;26(3):194–202. doi:10.1177/1059840510366022 [55] | 2010 | Midwest | 2007 | Investigate the influences of mothers’ intentions to vaccinate their daughters against HPV | Cross-sectional survey | 217 | Parents of adolescents | Theory of Planned Behavior | Intention to vaccinate | Attitudes were the strongest predictor of mothers’ intentions to vaccinate (β = 0.61, p < 0.001). Mothers with subjective norms that were in support of the vaccine were more likely to intend to vaccinate (β = 0.16, p < 0.05). | ||

| Askelson NM, Campo S, Smith S, Lowe JB, Dennis L, Andsager J. Assessing physicians’ intentions to talk about sex when they vaccinate nine-year-old to 15-year-old girls against HPV. Sex Educ. 2011;11(4):431–441. doi:10.1080/14681811.2011.595252 [56] | 2011 | Midwest | Not listed | Assess whether physicians would use HPV vaccination to communicate with young female patients about sex | Cross-sectional study | 207 | Provider | Theory of Planned Behavior | Intention to vaccinate | Most physicians intended to talk about sexually transmitted infections when they vaccinate against HPV (90.3%). Physicians’ intentions to talk about sex are influenced by attitudes (β = 0.18, p < 0.05), subjective norms (β = 0.53, p < 0.001), and perceived behavioral control (β = 0.15, p < 0.05). | ||

| Askelson NM, Ryan G, Seegmiller L, Pieper F, Kintigh B, Callaghan D. Implementation Challenges and Opportunities Related to HPV Vaccination Quality Improvement in Primary Care Clinics in a Rural State. J Community Health Aug. 2019;44(4):790–795. doi:10.1007/s10900-019-00676-z [57] | 2019 | Midwest | 2017 | Understand the decision-making process of intervention selection and implementation from the perspective of Vaccine for Children (VHC) liaisons | Cross-sectional study | 115 | Clinics | How HPV intervention selection decisions are made and the extent of implementation | Respondents (VFC liaisons) reported decisions about vaccine QI were made by multiple actors within their own clinics (45.1%), by a clinic manager in charge of multiple clinics (33.0%) and/or at a centralized administrative office (35.2%). Additionally, the majority of respondents considered external actors, like insurance companies (52.7%) or Medicaid/Medicare (50.5%), important to the decision-making process. | |||

| Ayres S, Gee A, Kim S. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Knowledge, Barriers, and Recommendations Among Healthcare Provider Groups in the Western United States. J Cancer Educ Dec. 2022;37(6):1816–1823. doi:10.1007/s13187-021-02047-6 [58] | 2021 | West | 2019 | Compare differences in same-day HPV vaccination recommendation at clinics Mountain West (MW) in states between healthcare provider and staff groups, and compare different provider groups’ perceived challenges associated with HPV vaccination, HPV vaccination knowledge, HPV recommendation practices, and same-day HPV vaccination recommendation | Cross-sectional study | 99 | Providers | Provider challenges and knowledge, and recommendation practices, and same-day HPV vaccination | Clinicians had a higher knowledge of HPV vaccination, identified more challenges that limit HPV vaccination, and had better HPV recommendation practices. There was no difference between clinicians and OTMs on the tendency of the patients to receive vaccine on same day as recommended. No significant differences were found between rural and urban subgroups on demographics or survey responses. | |||

| Beck A, Bianchi A, Showalter D. Evidence-Based Practice Model to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake: A Stepwise Approach. Nurs Womens Health. 2021;25(6):430–436. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2021.09.006 [59] | 2021 | South | 2018–2019 | Increase uptake of HPV vaccination by implementing HPV education along with a strong provider recommendation to parents of youth and adolescents | Controlled Trial | 24 | Clinic | Evidence-based practice model | HPV vaccine initiation and completion | Of all the 24 vaccine-eligible patients, all 24 ended up receiving initiation of the vaccine or completed a previously started series. | ||

| Bednarczyk RA, Whitehead JL, Stephenson R. Moving beyond sex: Assessing the impact of gender identity on human papillomavirus vaccine recommendations and uptake among a national sample of rural-residing LGBT young adults. Papillomavirus Res. 2017;3:121–125. doi:10.1016/j.pvr.2017.04.002 [60] | 2017 | National | 2014 | Compare HPV vaccine recommendation and uptake by self-reported sex assigned at birth and current gender identity | Cross-sectional survey | 660 | Adults | Healthcare provider HPV vaccine recommendation and HPV vaccine Initiation | Receipt of HPV vaccination recommendation and at least one HPV vaccine dose was higher for female SAAB (47% and 44%, respectively) compared to male SAAB (17% and 14%, respectively), as well as female or transmale gender identity compared to male or transfemale gender identity. Approximately half of vaccinated respondents reported receiving HPV vaccine between 13 and 17 years of age. | |||

| Berenson AB, Hirth JM, Kuo YF, Rupp RE. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of an all-inclusive postpartum human papillomavirus vaccination program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224(5):504.e1–504.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.11.033 [61] | 2021 | South | 2012–2019 | Examine the success and limitations of a program that promotes HPV vaccination to young adult women postpartum after expansion | Mixed methods | 6961 | Other (young postpartum women) | HPV vaccine completion | In the initial program, 76.9% completed the series, and in the expansion program, 73.5% completed the series. | |||

| Blake KD, Ottenbacher AJ, Finney Rutten LJ, et al. Predictors of Human Papillomavirus Awareness and Knowledge in 2013. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):402–410. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.024 [62] | 2015 | National | 2013 | Assess current population awareness of and knowledge about HPV and the HPV vaccine and the contribution of sociodemographic characteristics to disparities in HPV awareness and knowledge. | Cross-sectional Survey | 3103 | Adults | HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge | Sociodemographic characteristics associated with HPV knowledge/awareness | 68% had heard of HPV and the HPV vaccine, and 62% knew that HPV causes cervical cancer. | Age and sex impacted awareness and knowledge of HPV and the vaccine. Education, race, health insurance access, and internet access affected HPV and vaccine awareness, while rurality, education, and race affected some HPV knowledge questions. Those in rural areas were less likely than those in urban areas to know that HPV causes cervical cancer [aOR = 0.54 (0.30–0.98), p < 0.05]. | |

| Boitano TKL, Daniel C, Kim Y il, Straughn JM, Peral S, Scarinci I. Beyond words: Parental perceptions on human papillomavirus vaccination recommendations and its impact on uptake. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101596. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101596 [63] | 2021 | South | 2019–2020 | Evaluate the impact of provider recommendations regarding HPV vaccination uptake in a rural setting | Cross-sectional survey | 368 | Parents | HPV vaccine Initiation and Intention to vaccinate | Approximately 40% indicated receiving a recommendation from a provider to vaccinate their child. Parental impression from the recommendation of HPV vaccination being “important” was significantly associated with the child being vaccinated that day (OR = 7.31, 95% CI: 2.20–24.3) as well as scheduling HPV vaccination (OR = 3.17, 95% CI: 1.01–9.92). Parents who got the impression that “there was no hurry” were less likely to vaccinate their child that day (OR = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.09–0.59). | |||

| Boyce TG, Christianson B, Hanson KE, et al. Factors associated with human papillomavirus and meningococcal vaccination among adolescents living in rural and urban areas. Vaccine X. 2022;11:100180. doi:10.1016/j.jvacx.2022.100180 [64] | 2022 | Midwest | 2019 | Assess factors and barriers associated with adolescent HPV and MenACWY vaccination to understand the determinants of rural–urban differences | Cross-sectional study | 536 | Parents | Parents' perception of importance placed on HPV vaccine by HCP and HPV vaccine initiation | 60% of teens received one or more doses of HPV vaccine. Among teens who received Tdap, HPV, and MenACWY, more rural teens received the three vaccines on the same day than urban teens (62% vs. 44%, p = 0.02). Fewer rural parents reported discussion with their provider and HPV vaccination as being “very important” for their teen according to their provider (45% vs. 54%, p = 0.08). The HPV vaccine harms factor had the lowest mean score (least favorable toward vaccination) among the factors assessed and differed by residency. Mean HPV vaccine harms score was significantly lower among rural parents than urban parents (5.49 (SD = 2.32) vs. 6.05 (SD = 2.35), p = 0.006). | |||

| Brennan LP, Rodriguez NM, Head KJ, Zimet GD, Kasting ML. Obstetrician/gynecologists’ HPV vaccination recommendations among women and girls 26 and younger. Prev Med Rep. 2022;27:101772. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101772 [65] | 2022 | National | 2019 | Identify the factors that are most associated with an OB/GYN being a strong and frequent HPV vaccine recommender to girls and women 26 years of age or younger | Cross-sectional study | 205 | Providers | Competing Demands Model | Strength and frequency of provider recommendations | 56.3% (n = 116) were categorized as strong and frequent recommenders of the HPV vaccine. The clinic-level attributes were having the vaccine stocked (aOR = 2.66, 95%CI:1.02–6.93) and suburban (aOR = 3.31, 95%CI:1.07–10.19) or urban (aOR = 3.54, 95%CI:1.07–11.76) location versus rural for strong and frequent vaccine recommendations. Being a strong and frequent recommender was positively associated with believing other gynecologists frequently recommend the vaccine (aOR = 24.33, 95%CI:2.56–231.14) and believing that 50% or more of their patients are interested in receiving the vaccine (aOR = 2.77, 95%CI: 1.25–6.13). | ||

| Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements Versus Conversations to Improve HPV Vaccination Coverage: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1764 [66] | 2017 | South | 2015 | Determine the effectiveness of training providers to improve their recommendations using either presumptive “announcements” or participatory “conversations” | randomized clinical trial | 17,173 | Providers | HPV vaccine initiation | Six-month difference in HPV vaccination coverage for 13–17-year-olds and 3-month difference in all measures | 5.4% (95% CI: 1.1–9.7%) increase in vaccination initiation for patients who received announcement training compared to control clinics for 11–12-year-olds after 6 months. Conversation training did not differ from control clinics | At 6 months, neither announcement or conversation training was effective for changing coverage for other vaccination outcomes or for adolescents aged 13 through 17. After 3 months, clinics' announcement training had higher HPV initiation rates compared to control clinics. | |

| Britt R, Britt BC. The need to develop health campaigns for obtaining the HPV vaccine in rural and medically underserved college campuses. Educ Health. 2016;34:74–78 [67] | 2016 | Midwest | Not listed | Examine behavioral factors and their association with HPV vaccination | Cross-sectional study | 327 | Adults | Theory of Planned Behavior | Intention to vaccinate | There was no significant relationship between gender, intent, normative beliefs, or attitudes towards receiving the HPV vaccine. Neither attitudes nor perceived behavioral control were identified as significant predictors of intent, but subjective norms did serve as a significant predictor of receiving the HPV vaccine. | ||

| Britt RK, Englebert AM. Behavioral determinants for vaccine acceptability among rurally located college students. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2018;6(1):262–276. doi:10.1080/21642850.2018.1505519 [68] | 2018 | South | Not listed | Investigate the demands of family, school, social, and work and the potential relationships and their potential impact on attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control related to vaccination uptake | Cross-sectional study | 208 | Adults | Theory of Planned Behavior | Intention to vaccinate and HPV vaccine initiation | Attitudes towards vaccination uptake were positively related to increased work demands (r = 0.223, p < 0.001). Subjective norms were not significant with any variable. PBC and vaccination uptake were associated with work demands (r = 0.168, p < 0.001), school demands (r = 0.227, p < 0.01), and social demands (r = 0.056, p < 0.001). Intent to vaccinate was predicted by work demands (r = 0.143, p < 0.01), school demands (r = 0.130, p < 0.01), and social demands (r = 0.080, p < 0.01). | ||

| Brumbaugh JT, Sokoto KC, Wright CD, et al. Vaccination intention and uptake within the Black community in Appalachia. Health Psychol. 2023;42(8):557–566. doi:10.1037/hea000126 [69] | 2023 | South | 2020 | Identify and compare psychosocial predictors of COVID-19, flu, and HPV vaccination intention or behavior | Cross-sectional study | 336 | Adults | Andersen model | HPV vaccine initiation | Age was negatively associated (OR = 0.96, p = 0.023) and vaccine confidence was positively associated with HPV vaccination uptake (OR = 1.77, p < 0.001). Vaccine calculation remained significantly associated with HPV vaccination uptake in the final step of the overall model (OR = 1.32, p = 0.050) | ||

| Carman AL, McGladrey ML, Goodman Hoover A, Crosby RA. Organizational Variation in Implementation of an Evidence-Based Human Papillomavirus Intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2):301–308. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.011 [70] | 2015 | South | 2013–2014 | Implement the 1-2-3 Pap intervention in a public health setting and identify site-specific variations in its implementation | Quasi-experimental (pre- and post-implementation study) | 18 | Other (health departments) | HPV vaccine initiation and Implementation outcome: organizational readiness for change | The ORCA revealed variation in implementation strategies was widespread despite the “controls” provided by each site receiving the same instructions, incentives, and technical assistance. There was no statistical difference between ORCA scores and either channel selection or vaccine uptake. Among female patients, clinics using the waiting room channel had a mean total dose of 17.40. For clinics using the Internet distribution channel, the mean was 36.92. Interviews reinforced that there were wide implementation strategies among the LHD | |||

| Cataldi JR, Brewer SE, Perreira C, et al. Rural Adolescent Immunization: Delivery Practices and Barriers to Uptake. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(5):937–949. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2021.05.210107 [71] | 2021 | West | 2019 | Assess whether there were rural–urban differences in perceived parental vaccine confidence and beliefs, and adolescent immunization delivery practices among Colorado vaccine providers | Cross-sectional study | 437 | Providers | Health belief model | Barriers to adolescent vaccination and perceived parental vaccine attitudes and immunization practices | Percentage of clinicians that think parents would agree with vaccine benefits | Rural respondents were less likely than urban respondents to agree that most patients have insurance that covers vaccination (86% vs. 97%; p = 0.02). Rural respondents were less likely than urban respondents to indicate most parents in their practice would agree with statements about vaccine benefits (p = 0.02) and trust in medical providers (p = 0.05). Fewer providers strongly recommended HPV vaccine (81% for females, 80% for males 11 to 12 years) than other adolescent immunizations (Tdap, MenACWY, influenza: 87–97%). There were no significant differences between rural and urban responses for perceived parental HPV vaccination beliefs. | |

| Cates JR, Ortiz RR, North S, Martin A, Smith R, Coyne-Beasley T. Partnering with middle school students to design text messages about HPV vaccination. Health Promot Pract. 2015 Mar;16(2):244–55. doi: 10.1177/1524839914551365. Epub 2014 Sep 25. PMID: 25258431; PMCID: PMC5319196. [72] | 2015 | South | 2011–2012 | Examine the acceptability of text messages about HPV vaccination and message preferences among adolescents | Cross-sectional survey | 43 | Adolescents | Health Belief Model | Preferences for proposed text messages about HPV and HPV vaccine | Acceptability of using text messages to convey HPV vaccine information | More than 70% used text messaging with a cell phone. The text message with the best composite score (M = 2.33, SD = 0.72) for likeability, trustworthiness, and motivation to seek more information was a gain frame emphasizing reduction in HPV infection if vaccinated against HPV. Text messages with lower scores emphasized threats of disease if not vaccinated. | Participants (68%) preferred doctors as their information source. |

| Cates JR, Shafer A, Diehl SJ, Deal AM. Evaluating a County-Sponsored Social Marketing Campaign to Increase Mothers’ Initiation of HPV Vaccine for Their Preteen Daughters in a Primarily Rural Area. Soc Mark Q. 2011;17(1):4–26. doi:10.1080/15245004.2010.546943 [73] | 2012 | South | 2009 | Evaluate a social marketing campaign initiated by 13 North Carolina counties to raise awareness among parents and reduce barriers to accessing the vaccine in a primarily rural area | Quasi-experimental | 294 | Parents of adolescents and healthcare providers | Health Belief Model | HPV vaccine initiation | Awareness of Media campaign | HPV vaccination rates within six months of campaign launch were 2% higher for 9–13-year-old girls in two of the four intervention counties compared to 96 non-intervention counties. | Most respondents (82%) were aware of HPV messages, logos, or both. Overall awareness did not differ by daughters’ age, mother’s race, income level, or rural/urban residence. Mothers in the target age group were less likely to see posters “frequently” or “occasionally” than mothers with older daughters (44% vs. 69%, p < 0.05). Of respondent providers (n = 35), 94% used campaign brochures regularly or occasionally in conversations with parents. |

| Chido-Amajuoyi OG, Jackson I, Yu R, Shete S. Declining awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine within the general US population. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2020;17(2):420–427. doi:10.1080/21645515.2020.1783952 [74] | 2020 | National | 2008–2018 | Determine awareness of HPV and HPV vaccine in the US over the 10-year period | Cross-sectional survey | 21,325 | Adults | HPV and HPV vaccine awareness | Sociodemographic factors affecting awareness over time | The awareness of HPV decreased by 4.4%, and HPV vaccine awareness declined by 4.9% over time. | The lowest awareness was among racial minorities, rural residents, male respondents, those aged 65 years and older, as well as those with the lowest educational and socioeconomic standing | |

| Cunningham-Erves J, Koyama T, Huang Y, et al. Providers’ Perceptions of Parental Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Hesitancy: Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Cancer. 2019;5(2):e13832. doi:10.2196/13832 [75] | 2019 | South | 2018 | Characterize the reasons for and level of parental HPV vaccine hesitancy as perceived by pediatric providers in Middle Tennessee and identify provider-level and clinic-level factors influencing perceived parental hesitancy | Cross-sectional survey | 187 | Providers | Perceived parental barriers to HPV vaccine hesitancy among pediatric providers | The most common parental barriers to HPV vaccination Perceived by providers were concerns about HPV vaccine safety (88%), child being too young (78%), low risk of HPV infection for child through sexual activity (70%), and mistrust in vaccines (59%). Perceived parental HPV vaccine hesitancy was significantly associated with several provider-level factors: self-efficacy (p = 0.001), outcome expectations (p < 0.001), and confidence in HPV vaccine safety (p = 0.009). | |||

| Dang JHT, McClure S, Gori ACT. Implementation and evaluation of a multilevel intervention to increase uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine among rural adolescents. J Rural Health Jan. 2023;39(1):136–141. doi:10.1111/jrh.12690 [76] | 2023 | West | 2018–2020 | Evaluate the effectiveness of a multilevel evidence-based intervention aimed at increasing HPV vaccination coverage among rural adolescent patients in a rural health clinic | Controlled Trial | 498 | Adolescents | Initiation and completion | Adolescent patients ages 11–17 who had initiated the HPV vaccine series (82.7% vs. 52.4%, p < 0.0001) and completed the vaccine series (58.0% vs. 27.0%, p < 0.0001) were significantly greater at follow-up compared to baseline. | |||

| Daniel CL, Lawson F, Vickers M, et al. Enrolling a rural community pharmacy as a Vaccines for Children provider to increase HPV vaccination: a feasibility study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11304-8 [77] | 2021 | South | 2019–2020 | Examine the feasibility and potential effectiveness of enrolling a rural, community pharmacy as a VFC provider | pilot study | 1 | HPV-eligible community members | HPV vaccine initiation | Pharmacy VFC enrollment feasibility measures | 166 vaccines were administered to 89 adolescents, which included 55 HPV doses, 53 Tdap doses, 45 Meningococcal doses, and 13 Influenza doses. 64% (64) were VFC patients. The VFC intervention had positive feedback in the community and improved access to VFC-approved providers | The pharmacy increased overall prescription revenue by 34.1% (compared to a 6.9% increase for this time period in the previous year) and had a 17.8% increase in Medicaid prescriptions filled, thought to be heavily influenced by the added Medicaid/VFC services. Total revenue increased 24.4% after introduction of the intervention, compared to an 8.0% increase the previous year | |

| Fernandez-Pineda M, Cianelli R, Villegas N, et al. Preferred HPV and HPV Vaccine Learning Methods to Guide Future HPV Prevention Interventions Among Rural Hispanics. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;60:139–145. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2021.04.026 [78] | 2021 | South | Not listed | Determine rural Hispanic parents’ preferred HPV and HPVV learning methods | qualitative | 23 | Parents | Rural Hispanic parents’ preferred HPV and HPVV learning methods | For parents, small educational sessions (“charlas”) were the most preferred way to learn about HPV and HPVV. Other possible modes were healthcare providers, community-wide campaigns, mail, pharmacy, radio/tv, word of mouth, research studies, CDs/DVDs, email, pamphlets, social media videos, and webpage posts. For families/children to learn about HPV and HPVV, school-based events were most preferred. Other modes included healthcare providers/teachers, healthcare centers/clinic short video clips, health fairs, educational sessions, telephone(texts), and social media posts. | |||

| Fish LJ, Harrison SE, McDonald JA, et al. Key stakeholder perspectives on challenges and opportunities for rural HPV vaccination in North and South Carolina. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(5). doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2058264 [79] | 2022 | South | 2019–2020 | Learn about barriers and opportunities to scaling up adolescent vaccination, including HPV vaccination, in rural areas | qualitative | 14 | Other (stakeholders) | Social Ecological framework | Key stakeholder perspectives on challenges to HPV vaccination in rural areas | Individual: misinformation/vaccine beliefs and attitudes to preventive care; Provider: provider shortage, hard to participate in VFC programs, lack of strong provider HPV vaccine recommendations; System: no state mandate for HPV vaccine and school enrollment, school nurses could help address provider gaps, expand current programs for adolescents to include vaccines | ||

| Ford M, Cartmell K, Malek A, et al. Evaluation of the First-Year Data from an HPV Vaccination Van Program in South Carolina, U.S. J Clin Med. 2023;12(4):1362. doi:10.3390/jcm12041362 [80] | 2023 | South | 2021–2022 | Assess the program’s effectiveness by increasing the HPV vaccine uptake in SC | observational | 552 | Adolescents and Adults | HPV vaccine initiation | 552 participants received vaccinations from the HPV Van Program with 243 of them receiving the HPV vaccine | |||

| Gilbert PA, Lee AA, Pass L, et al. Queer in the Heartland: Cancer Risks, Screenings, and Diagnoses among Sexual and Gender Minorities in Iowa. J Homosex. Published online October 19, 2020:1–17. doi:10.1080/00918369.2020.1826832 [81] | 2020 | Midwest | 2017 | Develop detailed epidemiologic profiles of Iowa’s SGM for cancer prevention | Cross-sectional study | 567 | Adults | HPV vaccine initiation | Less than half (41.8%) of those plausibly eligible individuals reported HPV vaccine initiation. The majority (80.0%) reported receiving two or three doses. Compared to ciswomen, cismen had 78% lower odds of reporting HPV vaccination initiation (OR = 0.22, 95% CI: 0.11–0.45) but there was no difference for transgender/genderqueer individuals. Examining sexual orientation differences, bisexual/pansexual respondents had over four-times higher odds and queer/other individuals had 2 times higher odds of reporting HPV vaccination initiation compared to gay/lesbian respondents (OR = 4.34, 95% CI: 2.18–8.62 and OR = 2.10, 95% CI: 1.11–3.97, respectively). | |||

| Goessl CL, Christianson B, Hanson KE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine beliefs and practice characteristics in rural and urban adolescent care providers. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13751-3 [82] | 2022 | Midwest | 2019 | Identify the HPV vaccine attitudes and practices that were most strongly associated with rural vs. urban providers | Cross-sectional survey | 437 | Providers | Provider HPV Vaccine Resources, Practices and Attitudes | Five vaccine factors were different between rural and urban providers, including evening/weekend appointments (aOR = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.36), standing vaccination orders (aOR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.61, 4.91), prior experience with vaccine quality improvement projects (aOR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.28, 0.98), providing HPV vaccine information before it is due (aOR = 3.10, 95% CI: 1.68, 5.71), and recommending HPV vaccine during urgent care visit (aOR = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.79). Other practices and attitudinal exposures were statistically similar between rural and urban providers. | |||

| Gunn R, Ferrara LK, Dickinson C, et al. Human Papillomavirus Immunization in Rural Primary Care. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):377–385. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.018 [83] | 2020 | West | 2018 | Identify the organizational structures and clinical workflows that enable rural, high-performing primary care clinics to support HPV vaccine delivery | mixed methods | 12 | Clinics | Positive Deviance framework | organizational structures and workflows | Four key themes were identified: (1) standardized workflows to identify patients due for the vaccine and had vaccine administration protocols, (2) have a vaccine champion, (3) clinical staff were comfortable providing immunizations regardless of visit type, and (4) clear, persuasive language to recommend or educate parents/patients about the vaccine’s importance | ||

| Harris KL, Tay D, Kaiser D. The perspectives, barriers, and willingness of Utah dentists to engage in human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine practices. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020;16(2):436–444. doi:10.1080/21645515.2019.1649550 [84] | 2019 | West | 2017–2018 | Examine the relationship between dental providers’ perspectives about their scope of practice, barriers, and willingness to engage and collaborate in HPV vaccination practices in the dental setting | Cross-sectional Survey | 203 | Other (Dentists) | Barriers to HPV vaccine among dentists and dentists’ willingness to engage in HPV vaccination practices and collaborate with primary care providers. | Majority of Utah dentists surveyed perceived that discussing the link between HPV and OPC and recommending the HPV vaccine is within their scope of practice, but not administration of the HPV vaccine. A significantly higher proportion of urban Utah dentists disagreed that they were concerned about the safety of the HPV vaccine (n = 141, 73.43%, p = 0.011), or that they were concerned about the liability related to the HPV vaccine (n = 103, 53.34%, p = 0.004) were compared with rural dental providers (n = 13, 6.77%; n = 13, 6.77%). Discussing, recommending, and administering the HPV vaccine did not significantly differ by dentists’ age group, rurality, time spent on patient education, or length of dental experience. | |||

| Harry ML, Asche SE, Freitag LA, et al. Human Papillomavirus vaccination clinical decision support for young adults in an upper midwestern healthcare system: a clinic cluster-randomized control trial. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(1). doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2040933 [85] | 2022 | Midwest | 2018–2019 | Test Clinical Decision Support with or without shared decision-making tools (SDMTs) on HPV vaccination rates compared to usual care (UC) | Randomized controlled trial | 34 clinics | Adults | HPV vaccine completion | The HPV vaccination series was completed by 12 months in 2.3% (95% CI: 1.6–3.2%) of CDS, 1.6% (95% CI: 1.1–2.3%) of CDS + SDMT, and 2.2% (95% CI: 1.6–3.0%) of UC patients, and at least one HPV vaccine was received by 12 months in 13.1% (95% CI: 10.6–16.1%) of CDS, 9.2% (95% CI: 7.3–11.6%) of CDS + SDMT, and 11.2% (95% CI: 9.1–13.7%) of UC patients. | |||

| Hatch BA, Valenzuela S, Darden PM. Clinic-level differences in human papillomavirus vaccination rates among rural and urban Oregon primary care clinics. J Rural Health Mar. 2023;39(2):499–507. doi:10.1111/jrh.12724 [86] | 2023 | West | 2019 | Compare HPV vaccination between rural and urban primary care clinics and examine the association of rurality with HPV vaccination | Cross-sectional study | 537 | Clinics | HPV vaccine initiation and completion | The mean rate of HPV vaccine ≥ 1 dose was lower among rural clinics (46.9% vs. 51.1%, p = 0.039), as was vaccination UTD (40.5% vs. 49.9%, p < 0.001) when compared to urban clinics. The rural/urban disparity was not significant after adjusting for other individual- and clinic-level characteristics. | |||

| Henry KA, Swiecki-Sikora AL, Stroup AM, Warner EL, Kepka D. Area-based socioeconomic factors and Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among teen boys in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2017;18(1). doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4567-2 [87] | 2017 | National | 2012–2013 | Examine associations between both individual-level and area-based factors and HPV vaccine initiation and completion among boys | Secondary data analysis | 19,518 | Adolescents | HPV vaccine initiation and completion | Area-based poverty was not statistically significantly associated with HPV vaccination initiation, but it was associated with completion, with boys living in high-poverty areas having higher odds of completing the series than boys in low-poverty areas. Boys from urban or densely populated areas have higher odds of initiation and completion compared to boys living in non-urban, less densely populated areas. | |||

| Jafari SDG, Appel SJ, Shorter DG. Risk Reduction Interventions for Human Papillomavirus in Rural Maryland. J Dr Nurs Pract. 2020;13(2):134–141. doi:10.1891/jdnp-d-19-00047 [88] | 2020 | South | 2017–2018 | Address patient or parental perceptions Leading to vaccine hesitancy and identify the vaccine impact from provider to patient education | Mixed methods | 416 | Adolescents/ providers | HPV vaccine initiation | A documentary movie for women aged 12–26 was implemented to decrease HPV-related risks; the impact was not significant. Direct provider to patient recommendations resulted in a 15% increase in HPV immunizations. | |||

| Kepka D, Christini K, McGough E, et al. Successful Multi-Level HPV Vaccination Intervention at a Rural Healthcare Center in the Era of COVID-19. Front Digit Health. 2021;3. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2021.719138 [89] | 2021 | West | 2019–2021 | Test HPV vaccination intervention that includes healthcare team training activities and patient reminders to reduce missed opportunities and improve the rate of appointment scheduling for HPV vaccination in a rural medical clinic | Quasi-experimental study | 402 | Parents, adolescents and adults | Missed opportunities for HPV vaccination | Missed opportunities for HPV vaccination declined significantly between the pre-intervention and the post-intervention period (21.6 vs. 8.1%, respectively, p = 0.002). Participants who recalled receipt of a vaccination reminder had 7.0 (95% CI 2.4–22.8) times higher unadjusted odds of scheduling a visit compared with those who did not recall receiving a reminder. The unadjusted odds of confirming that they had scheduled or were intending to schedule a follow-up appointment to receive the HPV vaccine were 4.9 (95% CI 1.51–20.59) times greater among those who had not received the vaccine for themselves or for their child. | |||

| Kepka D, Coronado GD, Rodriguez HP, Thompson B. Evaluation of a Radionovela to Promote HPV Vaccine Awareness and Knowledge Among Hispanic Parents. J Community Health. 2011;36(6):957–965. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9395-1 [90] | 2011 | West | 2008–2009 | Investigate the efficacy of messages delivered via a radionovela to improve HPV and HPV vaccine-related knowledge and attitudes | randomized controlled trial | 88 | Parents | HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and knowledge & attitudes/beliefs | Parents who listened to the HPV radionovela (intervention group) were more likely to confirm that HPV is a common infection (70% vs. 48%, p = 0.002), to deny that women are able to detect HPV (53% vs. 31%, p = 0.003), to know vaccine age recommendations (87% vs. 68%, p = 0.003), and to confirm multiple doses (48% vs. 26%, p = 0.03) than control group parents. | |||

| Kepka DL, Ulrich AK, Coronado GD. Low Knowledge of the Three-Dose HPV Vaccine Series among Mothers of Rural Hispanic Adolescents. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23(2):626–635. doi:10.1353/hpu.2012.0040 [91] | 2012 | West | 2009 | Investigate correlates of HPV vaccine uptake by adolescent daughters of rural Hispanic mothers | Cross-sectional survey | 78 | Parents | Social Ecological Framework | HPV vaccine initiation | Mothers who had heard of the HPV vaccine were more likely to have a vaccinated daughter (p < 0.01). Mothers who thought their daughter’s father would approve were more likely to have a vaccinated daughter (p = 0.004). Parents who believed that only one injection was necessary were more likely to have a vaccinated daughter (p = 0.009) | ||

| Kim S, Zhou K, Parker S, Kline KN, Montealegre JR, McGee LU. Perceived Barriers and Use of Evidence-Based Practices for Adolescent HPV Vaccination among East Texas Providers. Vaccines. 2023;11(4):728. doi:10.3390/vaccines11040728 [92] | 2023 | South | 2022 | Understand current clinical practices regarding HPV vaccination in rural East Texas primary health-care settings and assess health-care providers’ perceived barriers to HPV vaccination | Cross-sectional study | 27 | Clinics | Perceived barriers to HPV vaccination in clinics and strategies used by clinics to increase HPV vaccination rates | HPV vaccine-promoting clinical practices | The most prevalent perceived barrier was missed opportunities for vaccination (66.7%), and concern about vaccine hesitancy (44.4%) because of the pandemic. | Many clinics surveyed currently implement evidence-based practices to promote HPV vaccination, but using a “refusal to vaccinate” form (29.6%), having an identified HPV vaccine champion (29.6%), and recommending the HPV vaccine at age 9 (22.2%) were least implemented among these clinics. | |

| Koskan AM, Dominick LN, Helitzer DL. Rural Caregivers’ Willingness for Community Pharmacists to Administer the HPV Vaccine to Their Age-Eligible Children. J Cancer Educ Feb. 2021;36(1):189–198. doi:10.1007/s13187-019-01617-z [93] | 2021 | south | Not listed | Explore rural caregivers’ perceptions of receiving the HPV vaccine from their local pharmacist and determine preferences for education for both the vaccine and receiving vaccines from pharmacists | Qualitative | 26 | Providers | Caregivers’ perceptions of the HPV vaccine and their willingness for pharmacist- administered HPV vaccination | Awareness about the HPV vaccine, HPV vaccine barriers, and facilitators. | Most caregivers were unaware that pharmacists could offer adolescent vaccines, but most were willing to allow their children to receive the vaccine from this non-traditional source. The primary concern was pharmacist training for administering the HPV vaccine. | Caregivers preferred print fliers disseminated in various locations and Facebook for channels of health education about HPV vaccine availability in pharmacies. | |

| Kurani S, MacLaughlin KL, Jacobson RM, et al. Socioeconomic disadvantage and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination uptake. Vaccine. 2022;40(3):471–476. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.12.003 [94] | 2022 | Midwest | 2016–2018 | Examine HPV vaccine-related disparities by area deprivation using patient-level data from persons residing in a largely rural, Upper Midwest region | Retrospective cohort study | 54,573 | Adolescents | HPV vaccine initiation and completion | Individuals living in more deprived block groups were significantly less likely to initiate and complete HPV vaccinations compared to those living in the least deprived blocks. Individuals with rural residence had decreased probabilities of initiation compared to individuals living in urban areas. | |||

| Lee HY, Luo Y, Won CR, Daniel C, Coyne-Beasley T. HPV and HPV Vaccine Awareness Among African Americans in the Black Belt Region of Alabama. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;11(2):808–814. doi:10.1007/s40615-023-01562-0 [95] | 2023 | South | Not listed | Examine HPV and HPV vaccine awareness and associated factors among rural, Southern African Americans | cross-sectional survey | 257 | Adults | HPV and HPV vaccine awareness | Slightly more than half of the participants were aware of HPV (62.5%) and HPV vaccine (62.1%). Being single, having a family cancer history, and good self-reported health status were positively associated with both HPV and HPV vaccine awareness. Employment was positively associated with HPV awareness, and participation in social groups was positively associated with HPV vaccine awareness. | |||

| Manganello JA, Chiang SC, Cowlin H, Kearney MD, Massey PM. HPV and COVID-19 vaccines: Social media use, confidence, and intentions among parents living in different community types in the United States. J Behav Med Apr. 2023;46(1–2):212–228. doi:10.1007/s10865-022-00316-3 [96] | 2022 | National | 2021 | Assess information seeking around children’s health and vaccines, and vaccine confidence and intention/uptake among parents living in different community types for HPV and COVID-19 | Cross-sectional study | 452 | Parents | Intention to vaccinate | Social media use | For both HPV and COVID-19 vaccines, political affiliation was the only common factor associated with both vaccine confidence and intention/uptake. Parents who identified as Democrats compared to Republicans had greater confidence in the vaccines and had higher odds of vaccine intention/uptake for their children. | Use of Facebook was not associated with vaccine confidence. | |

| McMann N, Trout KE. Assessing the Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Sexually Transmitted Infections Among College Students in a Rural Midwest Setting. J Community Health Feb. 2021;46(1):117–126. doi:10.1007/s10900-020-00855-3 [97] | 2020 | Midwest | 2019 | Assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexual health among rural college students in Nebraska | Cross-sectional survey | 125 | Adults | Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of sexual health (including percentage with HPV vaccination). | Prevalence of HPV vaccination was 51% (n = 63) and was different among females and males (60% vs. 18%, p < 0.001) | |||

| Mohammed KA, Subramaniam DS, Geneus CJ, et al. Rural–urban differences in human papillomavirus knowledge and awareness among US adults. Prev Med. 2018;109:39–43. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.01.016 [98] | 2018 | National | 2013–2017 | Determine the prevalence of knowledge and awareness of HPV, the HPV vaccine, and HPV-associated cancers among rural and urban residents, and examine the association of rural/urban status with knowledge and awareness | Cross-sectional survey | 10,147 | Adults | Awareness, knowledge of HPV, the HPV vaccine, and HPV-associated cancers | Knowledge about HPV causing cervical, oral, anal, and penile cancers, as well as the knowledge about HPV being transmitted through sexual contact. | In comparison to rural respondents, the prevalence of awareness of HPV (67.2%; 95% CI: 67.0–69.2) and the HPV vaccine (65.8%; 95% CI: 64.2–67.1) was higher among urban respondents. Compared to urban residents, rural residents were less likely to be aware of HPV (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.53–0.86) and HPV vaccine (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.63–0.97). | Additionally, the prevalence of knowing that HPV causes cervical (75.4%; 95% CI: 72.5–77.3) and oral cancer (30.9%; 95% CI: 28.4–32.1), and knowing HPV is transmitted through sexual contact (65.9%; 95% CI: 63.6–67.2) was higher among urban residents than rural residents. | |

| Morales-Campos DY, McDaniel MD, Amaro G, Flores BE, Parra-Medina D. Factors Associated with HPV Vaccine Adherence among Latino/a Adolescents in a Rural, Texas-Mexico Border County. Ethn Dis. 2022;32(4):275–284. doi:10.18865/ed.32.4.275 [99] | 2022 | South | 2015–2018 | Examine HPV vaccine initiation and completion among Hispanic adolescents in a rural, Texas-Mexico border county | Cross-sectional survey | 1832 | Parents | Ecological systems theory | HPV vaccine initiation and completion | Factors associated with HPV vaccine initiation and completion were female gender (p < 0.01), adolescent insurance status (p < 0.001), and receipt of required vaccines (p < 0.001). Adolescents who received mandatory vaccinations for school entry were five times more likely to initiate and complete the HPV vaccine series (OR = 5.39, p < 0.001) | ||

| Moss JL, Gilkey MB, Reiter PL, Brewer NT. Trends in HPV Vaccine Initiation among Adolescent Females in North Carolina, 2008–2010. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(11):1913–1922. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0509 [100] | 2012 | South | 2008–2010 | Assess trends and disparities in HPV vaccine initiation among female adolescents in North Carolina over 3 years | Secondary Data Analysis | 1427 | Parents | HPV vaccine initiation | HPV vaccine initiation increased over time (2008, 34%; 2009, 41%; 2010, 44%). This upward trend was present within 11 subpopulations of girls, including those who lived in rural areas, were of minority (non-black/non-white) race, or had not recently received a preventive check-up. | |||

| Moss JL, Gilkey MB, Rimer BK, Brewer NT. Disparities in collaborative patient–provider communication about human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12(6):1476–1483. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1128601 [101] | 2016 | National | 2010 | Understand how collaborative communication operates in vaccination decisions across demographic groups | Cross-sectional study | 4124 | Parents | Charles and Gafni framework (shared treatment decision-making model) | HPV vaccine initiation | Disparities in collaborative communication accounted for geographic variation in HPV vaccination, specifically, the higher rates of uptake in the urban/suburban vs. rural areas (p < 0.01). Half of parents (53%) in the survey reported collaborative communication. Poor, less educated, Spanish-speaking, Southern, and rural parents, and parents of non-privately insured and Hispanic adolescents, were least likely to report collaborative communication (all p < 0.05). | ||

| Newcomer SR, Caringi J, Jones B, Coyle E, Schehl T, Daley MF. A Mixed Methods Analysis of Barriers to and Facilitators of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Among Adolescents in Montana. Public Health Reports®. 2020;135(6):842–850. doi:10.1177/0033354920954512 [102] | 2020 | West | 2013–3017 | Identify barriers to and facilitators of adolescent HPV vaccination in Montana | Mixed methods | 326 | Adolescents | Vaccine Perceptions, Accountability and Adherence Model | HPV vaccine initiation | In Montana, initiation of the HPV vaccine series among adolescents aged 13–17 increased from 34.4% in 2013 to 65.5% in 2017. In NIS-Teen 2017 data (n = 326 adolescents), receiving a medical provider recommendation was significantly associated with series initiation (aPR = 2.3; 95% CI, 1.5–3.6). Among parents who did not intend to initiate the vaccine series for their adolescent within 12 months (n = 71), vaccine safety was the top concern (aPR = 24.5%; 95% CI, 12.1–36.9%). The two most commonly referenced themes were medical providers’ recommendation style and parental vaccine hesitancy as factors for HPV vaccination. | ||

| Newcomer SR, Freeman RE, Albers AN, et al. Missed opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccine series initiation in a large, rural U.S. state. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(1). doi:10.1080/21645515.2021.2016304 [103] | 2022 | West | 2020–2021 | Quantify the prevalence of missed opportunities to vaccinate adolescents against HPV when they presented for other vaccines, and to determine whether the risk of missed opportunities differed by vaccination clinics | Secondary data analysis | 47,622 | Adolescents | HPV vaccine initiation | Secondary: Immunization visits that were missed opportunities for initiating the human papillomavirus vaccine series for adolescents ages 11–17 years by clinic setting, Montana, 2014–2020. Tertiary: Associations between clinic setting, age, sex, and rurality with missed opportunities for initiating the human papillomavirus vaccine series for adolescents ages 11–17 years, Montana, 2014–2020 | Among 47,622 adolescents, 53.9% of 71,447 vaccination visits were missed opportunities. | Receiving vaccines in public health departments was significantly associated with higher risk of missed opportunities (aRR = 1.25, 95% confidence interval = 1.22–1.27, vs. private clinics). Receipt of vaccines in Indian Health Services and Tribal clinics was associated with fewer missed opportunities (aRR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.69–0.75, vs. private clinics). | |

| Nguyen CG, Pogemiller MI, Cooper MT, Garbe MC, Darden PM. Characteristics of Oklahoma Pediatricians Who Dismiss Families for Refusing Vaccines. Clin Pediatr Phila Jan. 2023;62(1):24–32. doi:10.1177/00099228221108801 [104] | 2023 | South | 2019 | To assess the frequency of declining new patients or dismissing current patients who request to delay or refuse vaccines, the delay/refusal of specific vaccine(s) that prompt pediatricians to decline/dismiss patients, and the demographics of pediatricians who decline or dismiss patients | Cross-sectional study | 122 | Providers | Dismiss or decline for some (but not all) vaccines | Secondary: the specific vaccines causing the delay/refusal resulting in decline/dismissal. Tertiary: demographic information about physicians who decline or dismiss patients. | 35% (34/98) of pediatricians dismissed current patients for refusing/delaying vaccine. 47% (48/103) declined accepting new patients due to refusing/delaying vaccine. Of the 48 physicians who declined patients, 25 (52%) declined new patients for refusing some but not all vaccines, and 23 (19%) declined new patients for refusing” all vaccines. | Secondary: Over 90% of respondents would dismiss/decline patients who refuse Dtap, Hib, PCV13, IPV, MMR, Varicella, Hep A, or Tdap. For influenza and HPV vaccines, less than 20% would dismiss or decline a patient over refusal or delay. Tertiary: More than 10 years in practice and being rural are more likely to dismiss current patients or decline new patients due to refusal for one, some, but not all, vaccines. | |

| * Osaghae I, Darkoh C, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, et al. Healthcare Provider’s Perceived Self-Efficacy in HPV Vaccination Hesitancy Counseling and HPV Vaccination Acceptance. Vaccines. 2023;11(2):300. doi:10.3390/vaccines11020300 [105] | 2022 | South | 2021 | Examine the relationship between HPV vaccination training of HCPs and HPV vaccination status assessment and recommendation | Cross-sectional survey | 1283 | Providers | Provider HPV vaccination status assessment and recommendation | 482 (47%) reported that they often/always assess. 537 (53%) never/sometimes assess. 756 (59%) reported they often/always recommend. 527 (41%) reported that they never/sometimes recommend. | |||

| * Osaghae I, Darkoh C, Chido-Amajuoyi OG, et al. Association of provider HPV vaccination training with provider assessment of HPV vaccination status and recommendation of HPV vaccination. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(6). doi:10.1080/21645515.2022.2132755 [106] | 2023 | South | 2021 | Determine the association between healthcare providers’ self-efficacy in HPV vaccination hesitancy counseling and HPV vaccination acceptance after initial and follow-up counseling sessions | Cross-sectional survey | 1283 | Providers | HPV vaccine initiation | HCPs who believed that they were very/completely confident in counseling HPV vaccine-hesitant parents had higher odds of observing HPV vaccination acceptance very often/always after an initial counseling session (aOR= 3.50; 95% CI: 2.25–5.44) and after follow-up counseling sessions (aOR = 2.58; 95% CI: 1.66–4.00) compared to HCPs that perceived they were not at all/somewhat/moderately confident. | |||

| Osegueda ER, Chi X, Hall JM, Vadaparampil ST, Christy SM, Staras SAS. County-Level Factors Associated With HPV Vaccine Coverage Among 11-Year-Olds to 12-Year-Olds Living in Florida in 2019. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72(1):130–137. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.09.005 [107] | 2023 | South | 2019 | Understand county-level characteristics associated with HPV vaccination rates | Cross-sectional study | 481,846 | Adolescents | HPV vaccine initiation and Completion | On average, the HPV vaccine initiation rate among the most urban counties at 65% (95%CI = 58.1–72.2) was higher than the 43% (95%CI = 36.4–50.5) HPV vaccine initiation rate among the most rural counties. HPV vaccine UTD prevalence is 21% in more urban counties and 10% for those living in rural counties. | |||

| Panagides R, Voges N, Oliver J, Bridwell D, Mitchell E. Determining the Impact of a Community-Based Intervention on Knowledge Gained and Attitudes Towards the HPV Vaccine in Virginia. J Cancer Educ Apr. 2023;38(2):646–651. doi:10.1007/s13187-022-02169-5 [108] | 2023 | South | 2016–2019 | Compare the impact of an educational film intervention on HPV intention to vaccinate and knowledge gained in urban and rural areas; To increase knowledge and intent to receive the HPV vaccine | quasi-experimental | 149 | Community | Health Belief Model | Attitudes, beliefs (intention), and knowledge | Changes in knowledge about HPV were statistically significant in two out of seven questions (p < 0.05). Changes in attitude were statistically significant in every attitude-based question about HPV (p < 0.05). There were significant differences in knowledge gained and attitudes towards the HPV vaccine when comparing urban and rural locations. | ||

| Paskett ED, Krok-Schoen JL, Pennell ML, et al. Results of a Multilevel Intervention Trial to Increase Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Uptake among Adolescent Girls. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(4):593–602. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.epi-15-1243 [109] | 2016 | Midwest | 2010–2015 | Test the efficacy of a multilevel intervention to improve the uptake of the HPV vaccine among Appalachian girls aged 9 to 17 years old in 12 counties in Appalachian Ohio | Randomized controlled trial | 456 | Multilevel | Intervention guided by the Health Belief Model, Theory of Reasoned Action, Extended Parallel Process Model, and Organizational Developmental Theory | HPV vaccine initiation | HPV vaccine uptake at 6 months and uptake of the second and third HPV vaccine shots. | 10 (7.7%) daughters of intervention participants received the first shot of the HPV vaccine within 3 months of being sent the intervention materials compared with 4 (3.2%) daughters of comparison group participants (p = 0.061). Provider knowledge about HPV increased (p < 0.001, from baseline to after education). | By 6 months, 17 (13.1%) daughters of intervention participants received the first HPV vaccine shot compared with eight (6.5%) daughters of comparison group participants (p = 0.002). |

| Pham D, Shukla A, Welch K, Villa A. Assessing knowledge of human papillomavirus among men who have sex with men (MSM) using targeted dating applications. Vaccine. 2022;40(36):5376–5383. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.07.048 [110] | 2022 | National | Not listed | Investigate knowledge regarding HPV, HPV-related cancers, and HPV vaccination rates among men who have sex with men (MSM) who had active accounts on two LGBTQ+ online dating applications | Cross-sectional survey | 3342 | Adults | HPV-related knowledge and HPV vaccine initiation and completion | What source has recommended the vaccine to the participant and comfort level receiving a vaccine from a dentist. | Half of the HPV vaccine-eligible respondents reported having received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine, while only 37.9% of the individuals aged 9–26 reported being vaccinated against HPV. Among the unvaccinated, 63.3% reported being interested in future vaccination, or learning more about it. There were no significant differences in vaccination status or HPV knowledge (except for cancers associated with HPV) between respondents from rural vs. urban locations. | Doctors/physicians/ nurses were reported to be the largest source of HPV vaccine recommendation. 42.2% of participants are comfortable receiving the HPV vaccine from a dentist. | |