Novel Intranasal Replication-Deficient NS1ΔC Flu Vaccine Confers Protection from Divergent Influenza A and B Viruses in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recombinant Influenza Viruses with Truncated NS1

2.2. Wild-Type Influenza Viruses

2.3. Inactivated Influenza Vaccines

2.4. Animals

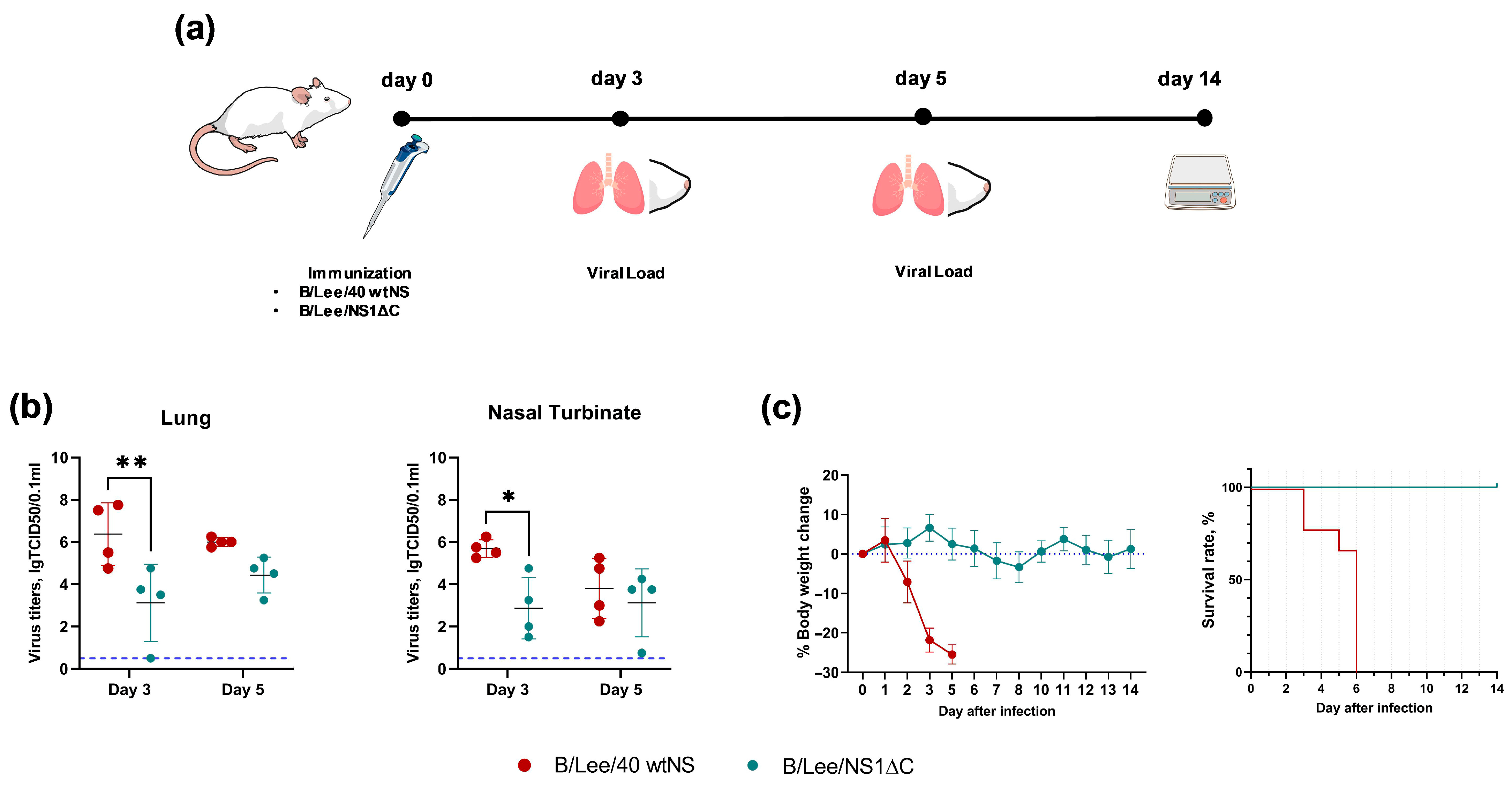

2.5. Safety Study

2.6. Protection Against the Influenza B/Victoria Virus by the Monovalent Formulation

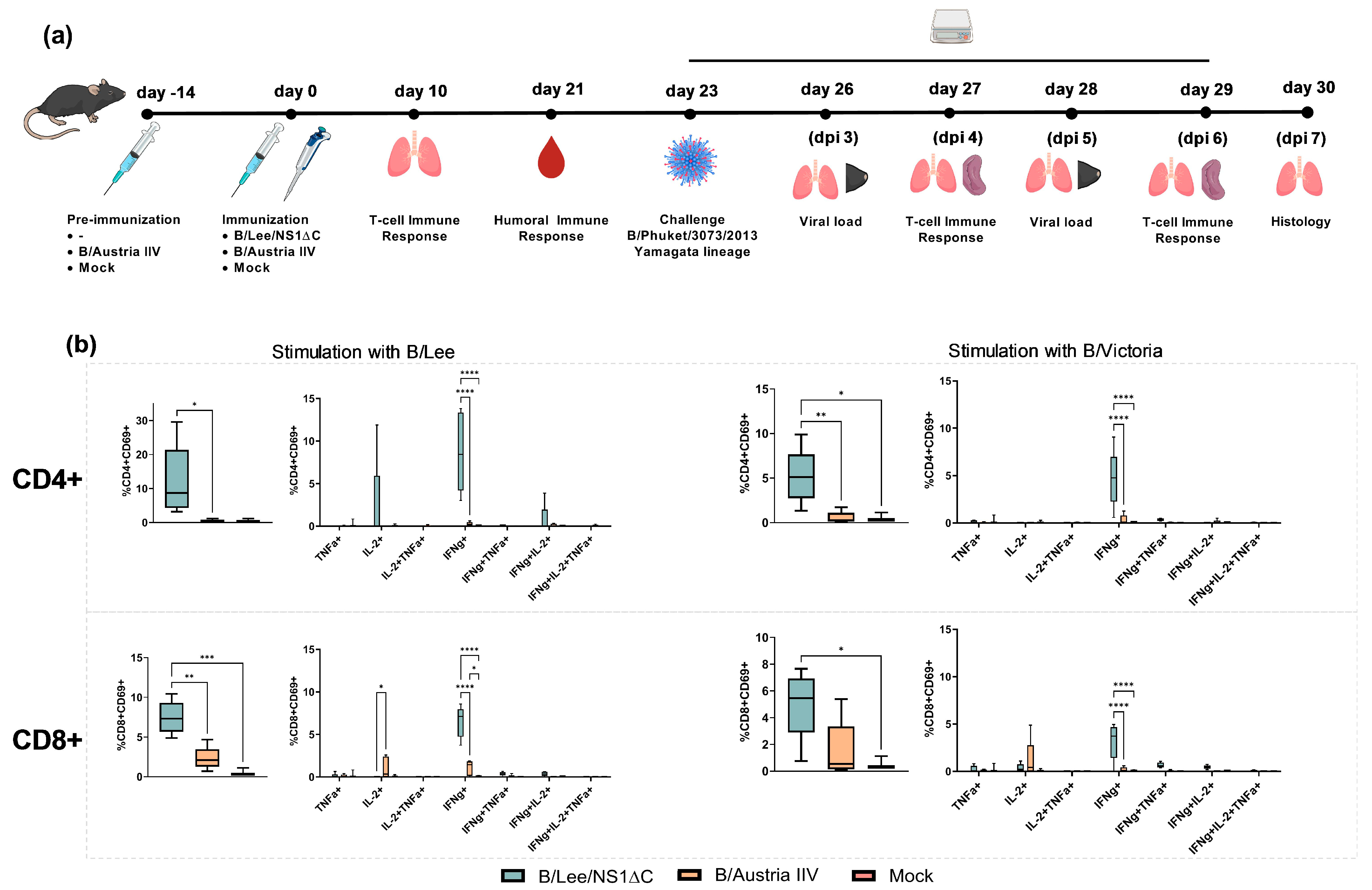

2.7. Immunogenicity of the Monovalent Formulation and Protection Against the Yamagata-Lineage Influenza B Virus

2.8. Protection Against Heterologous Influenza A and B Viruses by the Trivalent Formulation

2.9. Hemagglutination Inhibition Assay (HAI)

2.10. Real-Time PCR

2.11. Estimation of Virus Infectious Activity—TCID50 Assay

2.12. Histopathology

2.13. Isolation and Stimulation of Lung and Spleen Cell Cultures

2.14. Flow Cytometry

2.15. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Generation and Safety Profile of Influenza B Virus with a Truncated NS1 Protein

3.2. Immunogenicity of Influenza B Virus with a Truncated NS1 and Protection Against Influenza B/Yamagata Infection

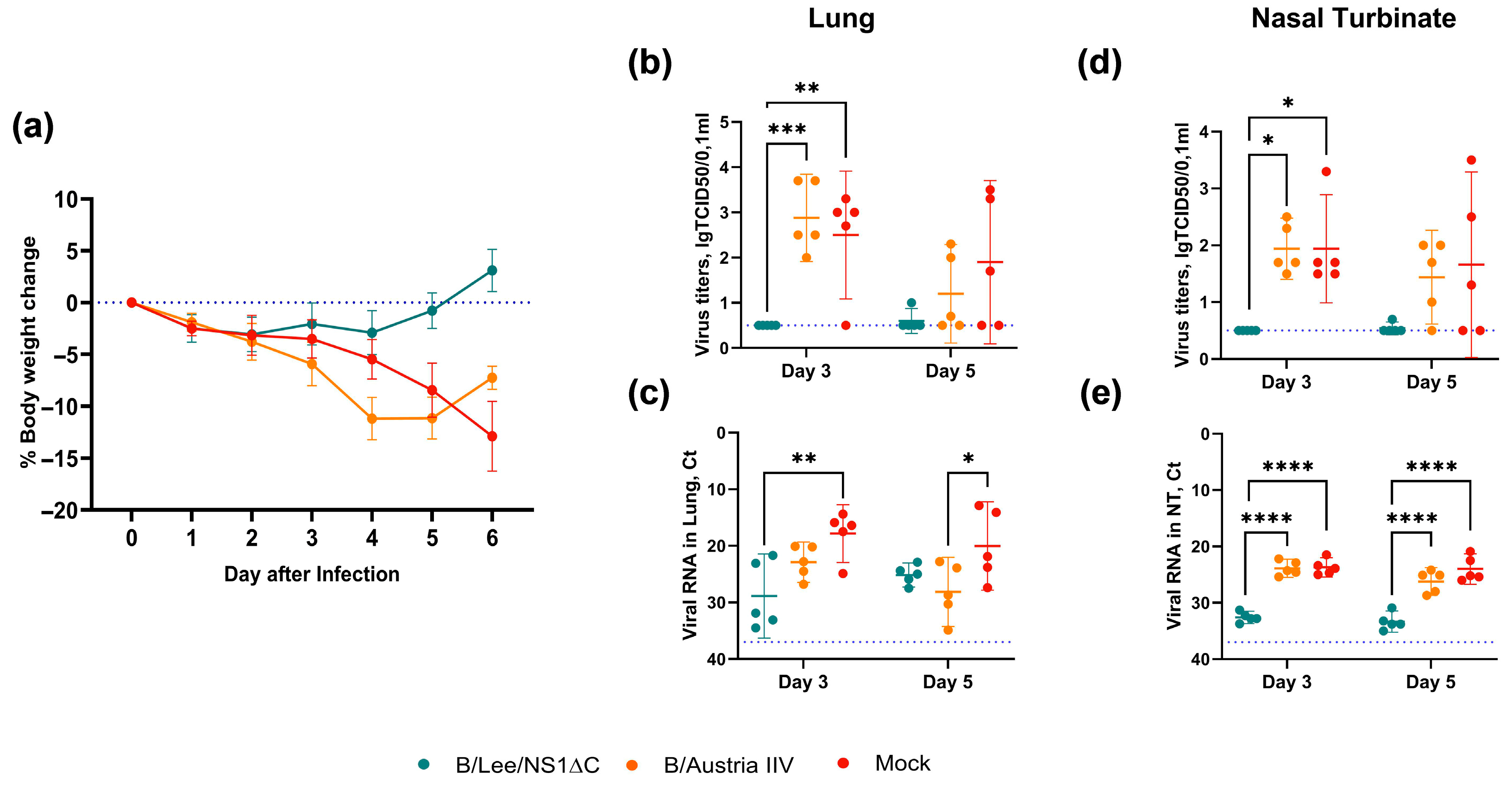

3.3. Protective Efficacy of Influenza B Virus with a Truncated NS1 Protein Against B/Victoria Challenge

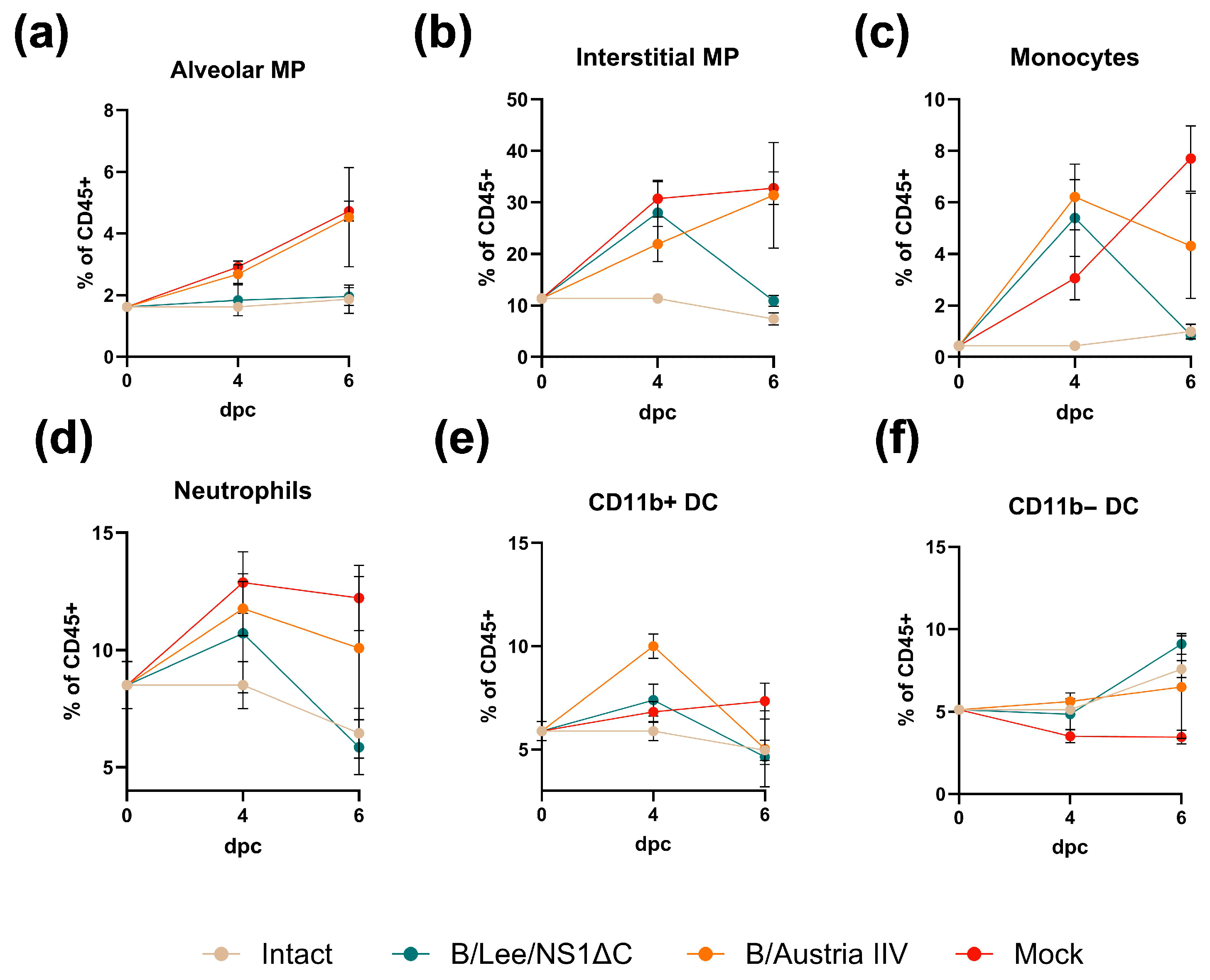

3.4. Cross-Protection by a Trivalent Formulation of NS1ΔC Influenza Viruses Against Divergent Influenza A and B Strains

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IIV | Inactivated Influenza Vaccine |

| HA | Haemagglutinin |

| LAIV | Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine |

| TIV | Trivalent Inactivated Influenza Vaccine |

| TCID | Tissue Culture Infective Dose |

| MLD | Mouse Lethal Dose |

| EID | Egg Infective Dose |

| ANOVA | Analysis Of Variance |

| Trm | Resident memory T cell |

| Tem | Effector memory T cell |

References

- Hoft, D.F.; Lottenbach, K.R.; Blazevic, A.; Turan, A.; Blevins, T.P.; Pacatte, T.P.; Yu, Y.; Mitchell, M.C.; Hoft, S.G.; Belshe, R.B. Comparisons of the Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses Induced by Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine and Inactivated Influenza Vaccine in Adults. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2017, 24, e00414–e00416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, P.; Tao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhan, S.; Sun, F. Real-world effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccination and age as effect modifier: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of test-negative design studies. Vaccine 2024, 42, 1883–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Song, J.Y.; Wie, S.H.; Choi, W.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, S.H.; Park, K.H.; et al. Real-world effectiveness of influenza vaccine over a decade during the 2011–2021 seasons-Implications of vaccine mismatch. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thwaites, R.S.; Uruchurtu, A.S.S.; Negri, V.A.; Cole, M.E.; Singh, N.; Poshai, N.; Jackson, D.; Hoschler, K.; Baker, T.; Scott, I.C.; et al. Early mucosal events promote distinct mucosal and systemic antibody responses to live attenuated influenza vaccine. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolla, A.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; Smith, J.M.; Brooks, A.G.; Kedzieska, K.; Heath, W.R.; Reading, P.C.; Wakim, L.M. Resident memory CD8+ T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaam6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, N.; Takeishi, K. Change in the efficacy of influenza vaccination after repeated inoculation under antigenic mismatch: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2018, 36, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Sesma, A.; Marukian, S.; Ebersole, B.J.; Kaminski, D.; Park, M.S.; Yuen, T.; Sealfon, S.C.; García-Sastre, A.; Moran, T.M. Influenza virus evades innate and adaptive immunity via the NS1 protein. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 6295–6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurygina, A.P.; Shuklina, M.; Ozhereleva, O.; Romanovskaya-Romanko, E.; Kovaleva, S.; Egorov, A.; Lioznov, D.; Stukova, M. Truncated NS1 Influenza A Virus Induces a Robust Antigen-Specific Tissue-Resident T-Cell Response and Promotes Inducible Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Formation in Mice. Vaccines 2025, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.R.; Bielefeldt-Ohmann, H.; García-Sastre, A.; Tumpey, T.M.; Van Hoeven, N.; Carter, V.S.; Thomas, M.J.; Proll, S.; Solórzano, A.; Billharz, R.; et al. Functional genomic and serological analysis of the protective immune response resulting from vaccination of macaques with an NS1-truncated influenza virus. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 11817–11827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zheng, M.; Lau, S.Y.; Chen, P.; Mok, B.W.-Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Huang, X.; Cremin, C.J.; Song, W.; et al. Generation of DelNS1 Influenza Viruses: A Strategy for Optimizing Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccines. mBio 2019, 10, e02180-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wressnigg, N.; Shurygina, A.P.; Wolff, T.; Redlberger-Fritz, M.; Popow-Kraupp, T.; Muster, T.; Egorov, A.; Kittel, C. Influenza B mutant viruses with truncated NS1 proteins grow efficiently in Vero cells and are immunogenic in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, R.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Fraser, K.A.; Ayllon, J.; García-Sastre, A.; Palese, P. Influenza B virus NS1-truncated mutants: Live-attenuated vaccine approach. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10580–10590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talon, J.; Salvatore, M.; O’Neill, R.E.; Nakaya, Y.; Zheng, H.; Muster, T.; García-Sastre, A.; Palese, P. Influenza A and B viruses expressing altered NS1 proteins: A vaccine approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 4309–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.C.; Guan, R.; Hamilton, K.; Aramini, J.M.; Mao, L.; Wang, S.; Krug, R.M.; Montelione, G.T. A Second RNA-Binding Site in the NS1 Protein of Influenza B Virus. Structure 2016, 24, 1562–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoffmann, E.; Neumann, G.; Kawaoka, Y.; Hobom, G.; Webster, R.G. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6108–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, E.; Mahmood, K.; Yang, C.F.; Webster, R.G.; Greenberg, H.B.; Kemble, G. Rescue of influenza B virus from eight plasmids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11411–11416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissarov, A.; Fadeev, A.; Sergeeva, M.; Petrov, S.; Sintsova, K.; Egorova, A.; Pisareva, M.; Buzitskaya, Z.; Musaeva, T.; Danilenko, D.; et al. Rapid spread of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses with a new set of specific mutations in the internal genes in the beginning of 2015/2016 epidemic season in Moscow and Saint Petersburg (Russian Federation). Influ Other Respir. Viruses 2016, 10, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev, K.; Shurygina, A.-P.; Sergeeva, M.; Stukova, M.; Egorov, A. Intranasal Immunization with the Influenza A Virus Encoding Truncated NS1 Protein Protects Mice from Heterologous Challenge by Restraining the Inflammatory Response in the Lungs. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergeeva, M.V.; Vasilev, K.; Romanovskaya-Romanko, E.; Yolshin, N.; Pulkina, A.; Shamakova, D.; Shurygina, A.P.; Muzhikyan, A.; Lioznov, D.; Stukova, M. Mucosal Immunization with an Influenza Vector Carrying SARS-CoV-2 N Protein Protects Naïve Mice and Prevents Disease Enhancement in Seropositive Th2-Prone Mice. Vaccines 2024, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, B.; Kirby, M.K.; Davis, W.G.; Warnes, C.; Liddell, J.; Liu, J.; Wu, K.-H.; Hassell, N.; Benitez, A.J.; Wilson, M.M.; et al. Multiplex Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR for Influenza A Virus, Influenza B Virus, and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 1821–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, L.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, C.W.; Jennings, R.; Clark, A.; Ali, M. Interference following dual inoculation with influenza A (H3N2) and (H1N1) viruses in ferrets and volunteers. J. Med. Virol. 1983, 11, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanova, J.R.; Ermachenko, T.A.; Alexandrova, G.I.; Tannock, G.A. Interference between cold-adapted (ca) influenza A and B vaccine reassortants or between ca reassortants and wild-type strains in eggs and mice. Vaccine 1994, 12, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universal Influenza Vaccine Technology Landscape. Update Nov 25, 2025. The IVR Initiative. University of Minnesota. Electronic Resource. Available online: https://ivr.cidrap.umn.edu/universal-influenza-vaccine-technology-landscape (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Ostrowsky, J.; Arpey, M.; Moore, K.; Osterholm, M.; Friede, M.; Gordon, J.; Higgins, D.; Molto-Lopez, J.; Seals, J.; Bresee, J. Tracking progress in universal influenza vaccine development. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2020, 40, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilyev, K.; Yukhneva, M.; Shurygina, A.-P.; Stukova, M.; Egorov, A. Enhancement of the Immunogenicity of Influenza A Virus by the Inhibition of Immunosuppressive Function of NS1 Protein. Microbiol. Indep. Res. J. 2018, 5, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pica, N.; Langlois, R.A.; Krammer, F.; Margine, I.; Palese, P. NS1-truncated live attenuated virus vaccine provides robust protection to aged mice from viral challenge. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 10293–10301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacheck, V.; Egorov, A.; Groiss, F.; Pfeiffer, A.; Fuereder, T.; Hoeflmayer, D.; Kundi, M.; Popow-Kraupp, T.; Redlberger-Fritz, M.; Mueller, C.A.; et al. A novel type of influenza vaccine: Safety and immunogenicity of replication-deficient influenza virus created by deletion of the interferon antagonist NS1. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mössler, C.; Groiss, F.; Wolzt, M.; Wolschek, M.; Seipelt, J.; Muster, T. Phase I/II trial of a replication-deficient trivalent influenza virus vaccine lacking NS1. Vaccine 2013, 31, 6194–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolodi, C.; Groiss, F.; Kiselev, O.; Wolschek, M.; Seipelt, J.; Muster, T. Safety and immunogenicity of a replication-deficient H5N1 influenza virus vaccine lacking NS1. Vaccine 2019, 37, 3722–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhuang, C.; Chu, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, H.; Huang, S.; Su, Y.; Lin, H.; Yang, C.; Jiang, H.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a live-attenuated influenza virus vector-based intranasal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in adults: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 and 2 trials. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Huang, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhuang, C.; Zhao, H.; Han, J.; Jaen, A.M.; Do, T.H.; Peter, J.G.; et al. COVID-19-PRO-003 Study Team. Safety and efficacy of the intranasal spray SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dNS1-RBD: A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.; Quan, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Zang, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, D.; Chu, X.; Zhuang, C.; Han, J.; et al. A randomized phase I trial of intranasal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dNS1-RBD in children aged 3–17 years. NPJ Vaccines 2025, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randomized Open Label Phase 1 Clinical Trial of Tb/Flu-01l Tuberculosis Vaccine Administered Intranasally or Sublingual in Bcg-Vaccinated Healthy Adults, Marina Stukova, Global Forum on Tb Vaccines, 20–23 February 2018, New Dehli, India. Electronic Recourse. Available online: https://tbvaccinesforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/5GF-Breakout-2-Stukova.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Prokopenko, P.; Matyushenko, V.; Rak, A.; Stepanova, E.; Chistyakova, A.; Goshina, A.; Kudryavtsev, I.; Rudenko, L.; Isakova-Sivak, I. Truncation of NS1 Protein Enhances T Cell-Mediated Cross-Protection of a Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine Virus Expressing Wild-Type Nucleoprotein. Vaccines 2023, 11, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappes, M.A.; Sandbulte, M.R.; Platt, R.; Wang, C.; Lager, K.M.; Henningson, J.N.; Lorusso, A.; Vincent, A.L.; Loving, C.L.; Roth, J.A.; et al. Vaccination with NS1-truncated H3N2 swine influenza virus primes T cells and confers cross-protection against an H1N1 heterosubtypic challenge in pigs. Vaccine 2012, 30, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauber, B.; Heins, G.; Wolff, T. The influenza B virus nonstructural NS1 protein is essential for efficient viral growth and antagonizes beta interferon induction. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 1865–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, A.; Brandt, S.; Sereinig, S.; Romanova, J.; Ferko, B.; Katinger, D.; Grassauer, A.; Alexandrova, G.; Katinger, H.; Muster, T. Transfectant influenza A viruses with long deletions in the NS1 protein grow efficiently in Vero cells. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 6437–6441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereinig, S.; Stukova, M.; Zabolotnyh, N.; Ferko, B.; Kittel, C.; Romanova, J.; Vinogradova, T.; Katinger, H.; Kiselev, O.; Egorov, A. Influenza virus NS vectors expressing the mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT-6 protein induce CD4+ Th1 immune response and protect animals against tuberculosis challenge. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2006, 13, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, O.; Arnheiter, H.; Pavlovic, J.; Staeheli, P. The Discovery of the Antiviral Resistance Gene Mx: A Story of Great Ideas, Great Failures, and Some Success. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018, 5, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zens, K.D.; Chen, J.K.; Farber, D.L. Vaccine-generated lung tissue-resident memory T cells provide heterosubtypic protection to influenza infection. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e85832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; He, J.; Chen, J.; Qi, R.; Yuan, L.; Shao, T.; Zhao, H.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. Intranasal influenza-vectored COVID-19 vaccine restrains the SARS-CoV-2 inflammatory response in hamsters. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnasinghe, R.; Salvatore, M.; Zheng, H.; Jangra, S.; Kehrer, T.; Mena, I.; Schotsaert, M.; Muster, T.; Palese, P.; García-Sastre, A. Interferon mediated prophylactic protection against respiratory viruses conferred by a prototype live attenuated influenza virus vaccine lacking non-structural protein 1. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Influenza Centre: Annual and Interim Reports. Report Prepared for the WHO Annual Consultation on the Composition of Influenza Vaccine for the Southern Hemisphere 2022. 13–23 September 2021. Available online: https://www.crick.ac.uk/research/platforms-and-facilities/worldwide-influenza-centre/annual-and-interim-reports (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Pekarek, M.J.; Madapong, A.; Wiggins, J.; Weaver, E.A. Adenoviral-Vectored Multivalent Vaccine Provides Durable Protection Against Influenza B Viruses from Victoria-like and Yamagata-like Lineages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlock, M.A.; Pierce, S.R.; Ross, T.M. Breadth of antibody activity elicited by an influenza B hemagglutinin vaccine is influenced by pre-existing immune responses to influenza B viruses. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e0070525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Chaves, S.S.; Perez, A.; D’Mello, T.; Kirley, P.D.; Yousey-Hindes, K.; Farley, M.M.; Harris, M.; Sharangpani, R.; Lynfield, R.; et al. Comparing clinical characteristics between hospitalized adults with laboratory-confirmed influenza A and B virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Vaudry, W.; Moore, D.; Bettinger, J.A.; Halperin, S.A.; Scheifele, D.W.; Jadvji, T.; Lee, L.; Mersereau, T.; on behalf of the Canadian Immunization Monitoring Program Active. Hospitalization for Influenza A Versus B. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20154643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, J.M.; Vuorinen, T.; Heikkinen, T. Comparative Severity of Influenza A and B Infections in Hospitalized Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2020, 39, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davido, B.; Lemarie, B.; Gault, E.; Jaffal, K.; Rottman, M.; Beaune, S.; Mamona, C.; Annane, D. Comparison between clinical outcomes in influenza A and B Infections: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. CMI Commun. 2025, 2, 105072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xie, Q.; Yu, P.; Zhang, J.; He, C.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C. Research Progress of Universal Influenza Vaccine. Vaccines 2025, 13, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, C.M.; Nachbagauer, R.; Mariottini, C.; Cuevas, F.; Feser, J.; Naficy, A.; Bernstein, D.I.; Guptill, J.; Walter, E.B.; Berlanda-Scorza, F.; et al. A chimeric haemagglutinin-based universal influenza virus vaccine boosts human cellular immune responses directed towards the conserved haemagglutinin stalk domain and the viral nucleoprotein. EBioMedicine 2024, 104, 105153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnasinghe, R.; Chang, L.A.; Pearl, R.; Jangra, S.; Aspelund, A.; Hoag, A.; Yildiz, S.; Mena, I.; Sun, W.; Loganathan, M.; et al. Sequential immunization with chimeric hemagglutinin ΔNS1 attenuated influenza vaccines induces broad humoral and cellular immunity. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, N.; Ebensen, T.; Guzman, C.A.; Ross, T.M. Intranasal administration of octavalent next-generation influenza vaccine elicits protective immune responses against seasonal and pre-pandemic viruses. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0035424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shamakova, D.; Shuklina, M.A.; Yolshin, N.; Romanovskaya-Romanko, E.; Shurygina, A.-P.; Kudrya, K.; Muzhikyan, A.; Sergeeva, M.V.; Stukova, M. Novel Intranasal Replication-Deficient NS1ΔC Flu Vaccine Confers Protection from Divergent Influenza A and B Viruses in Mice. Vaccines 2026, 14, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010043

Shamakova D, Shuklina MA, Yolshin N, Romanovskaya-Romanko E, Shurygina A-P, Kudrya K, Muzhikyan A, Sergeeva MV, Stukova M. Novel Intranasal Replication-Deficient NS1ΔC Flu Vaccine Confers Protection from Divergent Influenza A and B Viruses in Mice. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleShamakova, Daria, Marina A. Shuklina, Nikita Yolshin, Ekaterina Romanovskaya-Romanko, Anna-Polina Shurygina, Kira Kudrya, Arman Muzhikyan, Mariia V. Sergeeva, and Marina Stukova. 2026. "Novel Intranasal Replication-Deficient NS1ΔC Flu Vaccine Confers Protection from Divergent Influenza A and B Viruses in Mice" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010043

APA StyleShamakova, D., Shuklina, M. A., Yolshin, N., Romanovskaya-Romanko, E., Shurygina, A.-P., Kudrya, K., Muzhikyan, A., Sergeeva, M. V., & Stukova, M. (2026). Novel Intranasal Replication-Deficient NS1ΔC Flu Vaccine Confers Protection from Divergent Influenza A and B Viruses in Mice. Vaccines, 14(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010043