Hidden Targets in Cancer Immunotherapy: The Potential of “Dark Matter” Neoantigens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Neoantigen Cancer Vaccines

3. Why Neoantigen-Based Cancer Vaccines Are a Promising Future Cancer Therapy

| Platform | Name/ Formulation | Number of Neoantigens | Route | Type of Cancer/Setting | Combination | No. Patients | Study ID | T-Cell Responses | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide | NeoVax: SLP + poly-ICLC | nsSNV, up to 20 neoantigens | SC | Advanced RCC, Resected | ICI | 9 patients | Phase 1 NCT02950766 | Mostly CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells after expansion | Braun et al. [23] |

| NeoVax: SLP + poly-ICLC | nsSNV, up to 20 neoantigens | SC | Advanced melanoma, resected | ICI | 8 patients | Phase 1 NCT01970358 | Mostly CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells after expansion | Hu et al. [30] | |

| NeoVaxMI: SLP + poly-ICLC + montanide | nsSNV, 8–19 neoantigens | SC | Advanced melanoma, resected | ICI | 10 patients | Phase 1 PMID: 40645179 | CD8+ T-cell responses observed in 66.7% of patients | Blass et al. [11] | |

| mRNA | Autogene cevumeran, mRNA- LPX | nsSNV up to 20 neoantigens | IV | Resected PDAC | ICI + Chemotherapy | 16 patients | Phase 1 NCT04161755 | Mostly CD4+ T cells, low frequency CD8+ T cells | Rojas et al. [7] Sethna et al. [25] |

| mRNA-4157, mRNA-LNP | nsSNVs, up to 34 neoantigens | IM | Resected stage IIIB–IV melanoma | ICI | 157 patients | Phase 2b KEYNOTE-942 NCT03897881 | ~60% CD8+ and ~24% CD4+ T- cell responses | Weber et al. [8] Gainor et al. [24] | |

| DNA | GNOS-PV02 | nsSNVs, up to 40 neoantigens | IM | Advanced HCC | ICI | 36 patients | Phase 1/2 study NCT04251117 | Mostly CD8+ T-cell responses | Yarchoan et al. [27] |

| VB10.NEO | nsSNVs, frameshifts up to 20 neoantigens | IM | Melanoma, NSCLC, SCCHN, RCC | ICI | 41 patients | Phase 1 NCT05018273 | Mostly CD8+ T -cell responses | Krauss et al. [31] | |

| Viral | Heterologous ChAd68 and samRNA | nsSNVs, up to 20 neoantigens | IM | metastatic MSS-CRC, NSCLC or GEA | ICI | 14 patients | Phase 1/2 study NCT03639714 | CD8+ T-cell responses | Palmer et al. [32] |

| Heterologous ChAd68 and samRNA | nsSNVs, up to 20 neoantigens | IM | metastatic MSS-CRC | ICI | 104 patients | Phase 2/3 NCT05141721 | Not published yet | NCT05141721 |

4. Identification, Prioritisation, and Immunogenicity of Neoantigens

5. Heterogeneity in Canonical Neoantigen Immunogenicity: Implications for Expanded Antigen Discovery

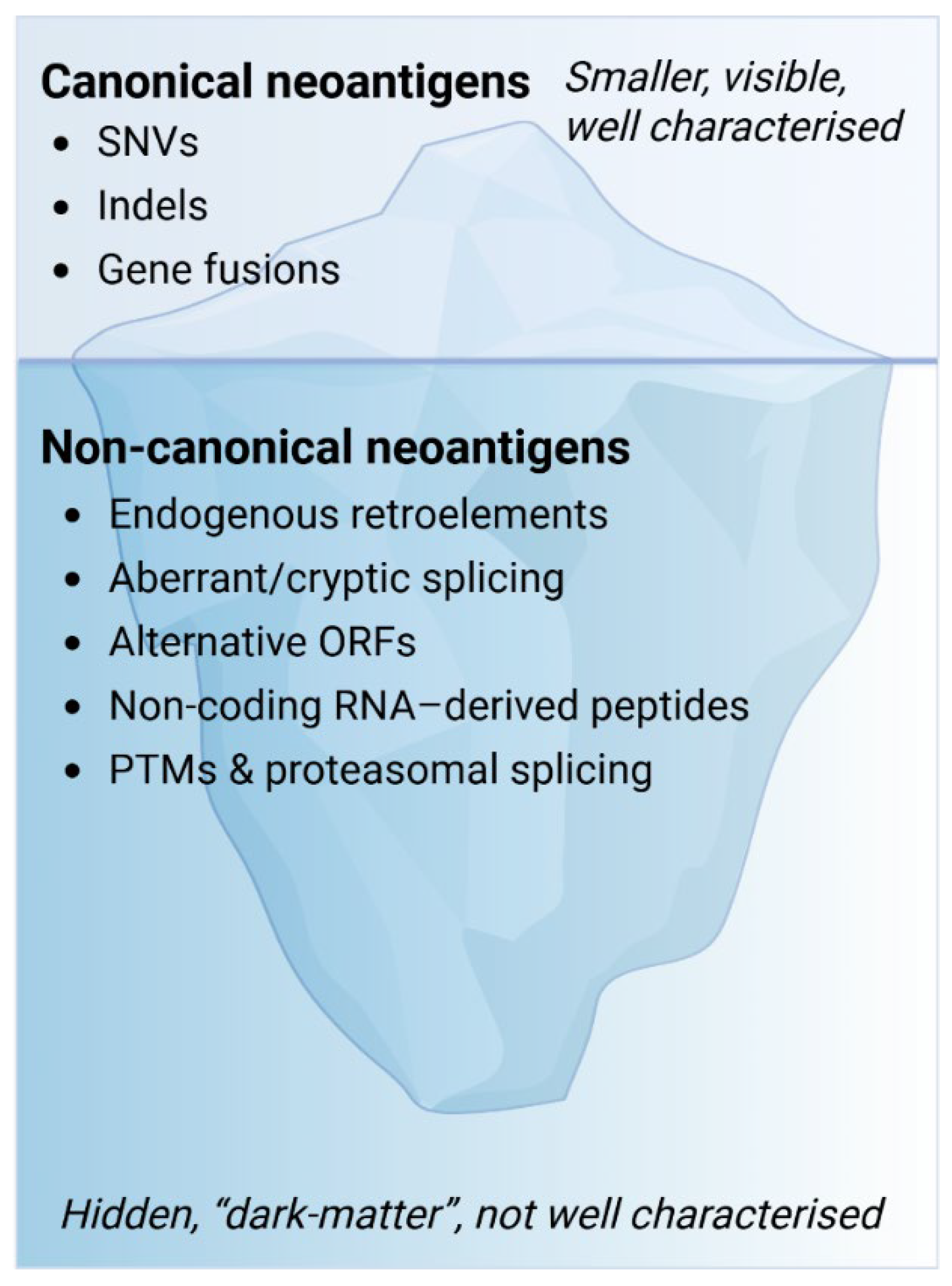

6. Beyond Canonical Neoantigens: The “Dark Matter” of the Antigenome

Conceptual Overview: Why Go Beyond the Exome?

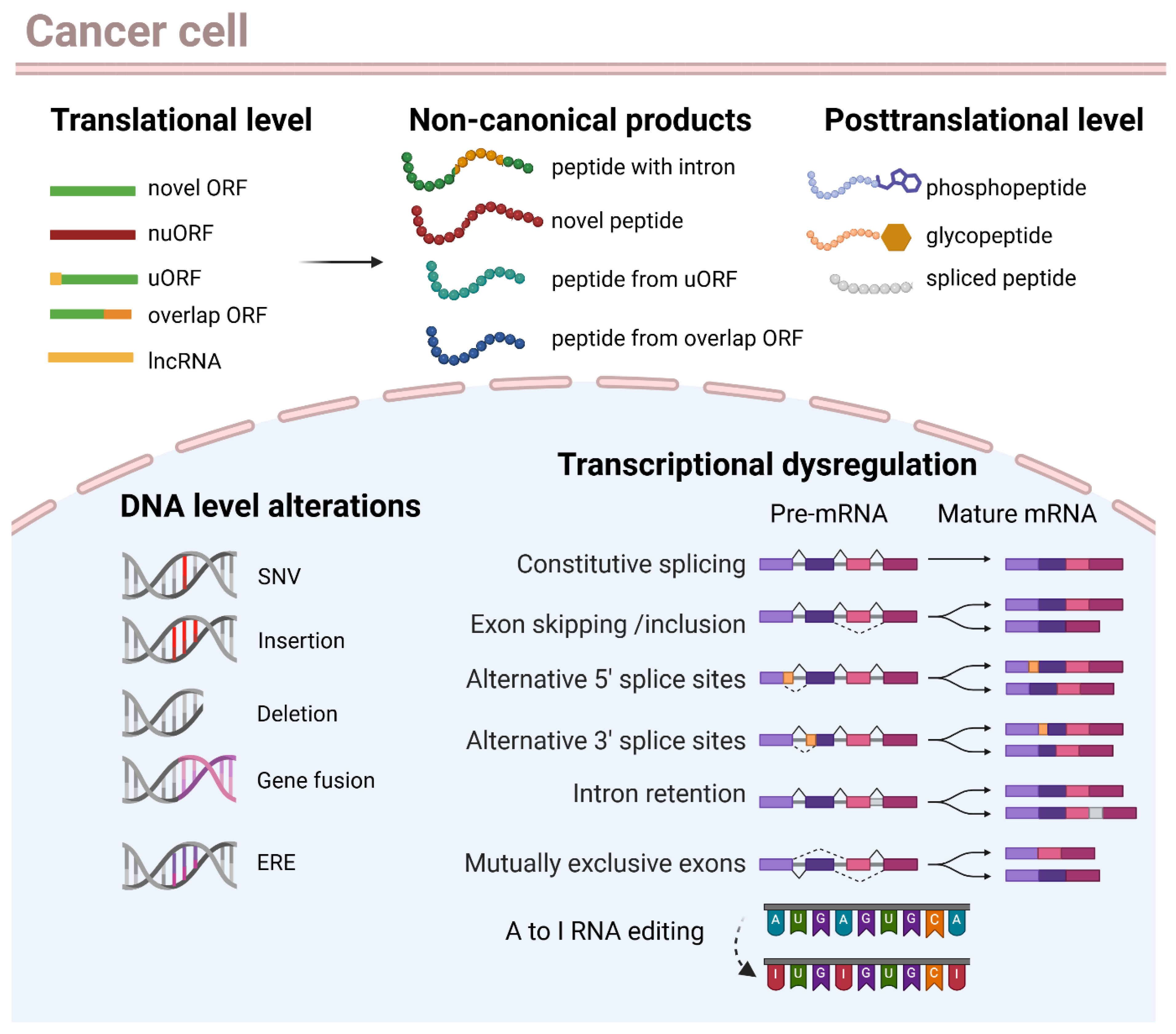

7. Biological Sources of Non-Canonical Neoantigens

7.1. Transcriptional Dysregulation: Alternative Splicing, Intron Retention, and RNA Editing

7.2. Alternative Translation Products

7.3. Endogenous Retroviral and Transposable Elements

7.4. Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs)

8. Illuminating the Dark Antigenome: Computational and Proteogenomic Approaches to Identify Non-Canonical Antigens

9. Bioinformatics Tools for Identification of Non-Canonical Neoantigens

10. Computational Tools to Detect Alternative Splicing-Derived Neoantigens

11. Beyond Splicing Events: Other Non-Canonical Transcript Classes

12. Integrated Proteogenomic and Translatomic Strategies

13. Prevalence and Biological Significance

14. Functional Immunogenicity and Clinical Relevance

14.1. Evidence of Immunogenicity in Murine Models

14.2. Large-Scale Human Studies: Immunogenicity and Clinical Relevance

15. Implications of Non-Canonical Neoantigens on Vaccine Development

16. Key Challenges and Considerations

17. Outlook and Future Directions

18. Standardisation, Shared Resources, and Reproducibility

19. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ikeda, H. Cancer immunotherapy in progress-an overview of the past 130 years. Int. Immunol. 2025, 37, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, P.M.; Chaft, J.E.; Smith, K.N.; Anagnostou, V.; Cottrell, T.R.; Hellmann, M.D.; Zahurak, M.; Yang, S.C.; Jones, D.R.; Broderick, S.; et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 Blockade in Resectable Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1976–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggermont, A.M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Grob, J.J.; Dummer, R.; Wolchok, J.D.; Schmidt, H.; Hamid, O.; Robert, C.; Ascierto, P.A.; Richards, J.M.; et al. Prolonged Survival in Stage III Melanoma with Ipilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohaan, M.W.; Borch, T.H.; van den Berg, J.H.; Met, O.; Kessels, R.; Geukes Foppen, M.H.; Stoltenborg Granhoj, J.; Nuijen, B.; Nijenhuis, C.; Jedema, I.; et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte Therapy or Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2113–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Wargo, J.A.; Ribas, A. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell 2017, 168, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Tureci, O. Personalized vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Science 2018, 359, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, L.A.; Sethna, Z.; Soares, K.C.; Olcese, C.; Pang, N.; Patterson, E.; Lihm, J.; Ceglia, N.; Guasp, P.; Chu, A.; et al. Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2023, 618, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.S.; Carlino, M.S.; Khattak, A.; Meniawy, T.; Ansstas, G.; Taylor, M.H.; Kim, K.B.; McKean, M.; Long, G.V.; Sullivan, R.J.; et al. Individualised neoantigen therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab monotherapy in resected melanoma (KEYNOTE-942): A randomised, phase 2b study. Lancet 2024, 403, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, P.A.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Chmielowski, B.; Govindan, R.; Naing, A.; Bhardwaj, N.; Margolin, K.; Awad, M.M.; Hellmann, M.D.; Lin, J.J.; et al. A Phase Ib Trial of Personalized Neoantigen Therapy Plus Anti-PD-1 in Patients with Advanced Melanoma, Non-small Cell Lung Cancer, or Bladder Cancer. Cell 2020, 183, 347–362.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, B.A.; Urba, W.J.; Jensen, S.M.; Page, D.B.; Curti, B.D.; Sanborn, R.E.; Leidner, R.S. Cancer’s Dark Matter: Lighting the Abyss Unveils Universe of New Therapies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2173–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blass, E.; Keskin, D.B.; Tu, C.R.; Forman, C.; Vanasse, A.; Sax, H.E.; Shim, B.; Chea, V.; Kim, N.; Carulli, I.; et al. A multi-adjuvant personal neoantigen vaccine generates potent immunity in melanoma. Cell 2025, 188, 5125–5141.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, P.A.; Hu, Z.; Keskin, D.B.; Shukla, S.A.; Sun, J.; Bozym, D.J.; Zhang, W.; Luoma, A.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Peter, L.; et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature 2017, 547, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, D.B.; Anandappa, A.J.; Sun, J.; Tirosh, I.; Mathewson, N.D.; Li, S.; Oliveira, G.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Felt, K.; Gjini, E.; et al. Neoantigen vaccine generates intratumoral T cell responses in phase Ib glioblastoma trial. Nature 2019, 565, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubin, M.M.; Zhang, X.; Schuster, H.; Caron, E.; Ward, J.P.; Noguchi, T.; Ivanova, Y.; Hundal, J.; Arthur, C.D.; Krebber, W.J.; et al. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature 2014, 515, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarchoan, M.; Johnson, B.A., 3rd; Lutz, E.R.; Laheru, D.A.; Jaffee, E.M. Targeting neoantigens to augment antitumour immunity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, N.; Furness, A.J.; Rosenthal, R.; Ramskov, S.; Lyngaa, R.; Saini, S.K.; Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Wilson, G.A.; Birkbak, N.J.; Hiley, C.T.; et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 2016, 351, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumont, C.M.; Vincent, K.; Hesnard, L.; Audemard, E.; Bonneil, E.; Laverdure, J.P.; Gendron, P.; Courcelles, M.; Hardy, M.P.; Cote, C.; et al. Noncoding regions are the main source of targetable tumor-specific antigens. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaau5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ely, Z.A.; Kulstad, Z.J.; Gunaydin, G.; Addepalli, S.; Verzani, E.K.; Casarrubios, M.; Clauser, K.R.; Wang, X.; Lippincott, I.E.; Louvet, C.; et al. Pancreatic cancer-restricted cryptic antigens are targets for T cell recognition. Science 2025, 388, eadk3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erhard, F.; Dolken, L.; Schilling, B.; Schlosser, A. Identification of the Cryptic HLA-I Immunopeptidome. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, R.; Mangalaparthi, K.K.; Madugundu, A.K.; Jessen, E.; Pathangey, L.; Magtibay, P.; Butler, K.; Christie, E.; Pandey, A.; Curtis, M. Immunogenic cryptic peptides dominate the antigenic landscape of ovarian cancer. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads7405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, S.R.; Shastri, N. Nowhere to hide: Unconventional translation yields cryptic peptides for immune surveillance. Immunol. Rev. 2016, 272, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, N.; Shen, G.; Gao, W.; Huang, Z.; Huang, C.; Fu, L. Neoantigens: Promising targets for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.A.; Moranzoni, G.; Chea, V.; McGregor, B.A.; Blass, E.; Tu, C.R.; Vanasse, A.P.; Forman, C.; Forman, J.; Afeyan, A.B.; et al. A neoantigen vaccine generates antitumour immunity in renal cell carcinoma. Nature 2025, 639, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainor, J.F.; Patel, M.R.; Weber, J.S.; Gutierrez, M.; Bauman, J.E.; Clarke, J.M.; Julian, R.; Scott, A.J.; Geiger, J.L.; Kirtane, K.; et al. T-cell Responses to Individualized Neoantigen Therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) Alone or in Combination with Pembrolizumab in the Phase 1 KEYNOTE-603 Study. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 2209–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethna, Z.; Guasp, P.; Reiche, C.; Milighetti, M.; Ceglia, N.; Patterson, E.; Lihm, J.; Payne, G.; Lyudovyk, O.; Rojas, L.A.; et al. RNA neoantigen vaccines prime long-lived CD8(+) T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2025, 639, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, J.; Powles, T.; Braiteh, F.; Siu, L.L.; LoRusso, P.; Friedman, C.F.; Balmanoukian, A.S.; Gordon, M.; Yachnin, J.; Rottey, S.; et al. Autogene cevumeran with or without atezolizumab in advanced solid tumors: A phase 1 trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarchoan, M.; Gane, E.J.; Marron, T.U.; Perales-Linares, R.; Yan, J.; Cooch, N.; Shu, D.H.; Fertig, E.J.; Kagohara, L.T.; Bartha, G.; et al. Personalized neoantigen vaccine and pembrolizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase 1/2 trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Goedegebuure, S.P.; Chen, M.Y.; Mishra, R.; Zhang, F.; Yu, Y.Y.; Singhal, K.; Li, L.; Gao, F.; Myers, N.B.; et al. Neoantigen DNA vaccines are safe, feasible, and induce neoantigen-specific immune responses in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, R.; Xie, L.; Shu, Y.; Gao, S.; Wang, P.; Su, X.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Personalized neoantigen pulsed dendritic cell vaccine for advanced lung cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Leet, D.E.; Allesoe, R.L.; Oliveira, G.; Li, S.; Luoma, A.M.; Liu, J.; Forman, J.; Huang, T.; Iorgulescu, J.B.; et al. Personal neoantigen vaccines induce persistent memory T cell responses and epitope spreading in patients with melanoma. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, J.; Krakhardt, A.; Eisenmann, S.; Ochsenreither, S.; Berg, K.C.G.; Kushekhar, K.; Fallang, L.-E.; Pedersen, M.W.; Torhaug, S.; Slot, K.B.; et al. Abstract CT274: Individualized APC targeting VB10.NEO cancer vaccines induce broad neoepitope-specific CD8 T cell responses in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors: Interim results from a phase 1/2a trial. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, CT274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.D.; Rappaport, A.R.; Davis, M.J.; Hart, M.G.; Scallan, C.D.; Hong, S.J.; Gitlin, L.; Kraemer, L.D.; Kounlavouth, S.; Yang, A.; et al. Individualized, heterologous chimpanzee adenovirus and self-amplifying mRNA neoantigen vaccine for advanced metastatic solid tumors: Phase 1 trial interim results. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1619–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blass, E.; Ott, P.A. Advances in the development of personalized neoantigen-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capietto, A.H.; Hoshyar, R.; Delamarre, L. Sources of Cancer Neoantigens beyond Single-Nucleotide Variants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, F.; Schrors, B.; Lower, M.; Tureci, O.; Sahin, U. Identification of neoantigens for individualized therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2022, 21, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Lee, K.W.; Srivastava, R.M.; Kuo, F.; Krishna, C.; Chowell, D.; Makarov, V.; Hoen, D.; Dalin, M.G.; Wexler, L.; et al. Immunogenic neoantigens derived from gene fusions stimulate T cell responses. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Wei, L.; Zhang, X. Computational methods and data resources for predicting tumor neoantigens. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynisson, B.; Alvarez, B.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: Improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartner, J.J.; Parkhurst, M.R.; Gros, A.; Tran, E.; Jafferji, M.S.; Copeland, A.; Hanada, K.I.; Zacharakis, N.; Lalani, A.; Krishna, S.; et al. A machine learning model for ranking candidate HLA class I neoantigens based on known neoepitopes from multiple human tumor types. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorani, E.; Rosenthal, R.; McGranahan, N.; Reading, J.L.; Lynch, M.; Peggs, K.S.; Swanton, C.; Quezada, S.A. Differential binding affinity of mutated peptides for MHC class I is a predictor of survival in advanced lung cancer and melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Dick, I.; Robinson, B.W.; Creaney, J.; Redwood, A. Neoantigen load as a predictor of relapse in early-stage NSCLC: Features that agonise and antagonise prognosis. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2025, 74, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwood, A.J.; Dick, I.M.; Creaney, J.; Robinson, B.W.S. What’s next in cancer immunotherapy?—The promise and challenges of neoantigen vaccination. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2038403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Xi, B.; Tan, W.; Chen, Z.; Wei, J.; Hu, M.; Lu, X.; Chen, D.; Cai, H.; Du, H. NeoaPred: A deep-learning framework for predicting immunogenic neoantigen based on surface and structural features of peptide-human leukocyte antigen complexes. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.; Coukos, G.; Bassani-Sternberg, M. Identification of tumor antigens with immunopeptidomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apavaloaei, A.; Zhao, Q.; Hesnard, L.; Cahuzac, M.; Durette, C.; Larouche, J.D.; Hardy, M.P.; Vincent, K.; Brochu, S.; Laverdure, J.P.; et al. Tumor antigens preferentially derive from unmutated genomic sequences in melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer. Nat. Cancer 2025, 6, 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani-Sternberg, M.; Braunlein, E.; Klar, R.; Engleitner, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Audehm, S.; Straub, M.; Weber, J.; Slotta-Huspenina, J.; Specht, K.; et al. Direct identification of clinically relevant neoepitopes presented on native human melanoma tissue by mass spectrometry. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, M.; Jhunjhunwala, S.; Phung, Q.T.; Lupardus, P.; Tanguay, J.; Bumbaca, S.; Franci, C.; Cheung, T.K.; Fritsche, J.; Weinschenk, T.; et al. Predicting immunogenic tumour mutations by combining mass spectrometry and exome sequencing. Nature 2014, 515, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, T.; Xu, H.; Liu, T. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Neoantigen Prediction. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 2376–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, L.R.; Gerstung, M.; Knappskog, S.; Desmedt, C.; Gundem, G.; Van Loo, P.; Aas, T.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Larsimont, D.; Davies, H.; et al. Subclonal diversification of primary breast cancer revealed by multiregion sequencing. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.; Khattra, J.; Yap, D.; Wan, A.; Laks, E.; Biele, J.; Ha, G.; Aparicio, S.; Bouchard-Cote, A.; Shah, S.P. PyClone: Statistical inference of clonal population structure in cancer. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leko, V.; Rosenberg, S.A. Identifying and Targeting Human Tumor Antigens for T Cell-Based Immunotherapy of Solid Tumors. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Liang, W.W.; Foltz, S.M.; Mutharasu, G.; Jayasinghe, R.G.; Cao, S.; Liao, W.W.; Reynolds, S.M.; Wyczalkowski, M.A.; Yao, L.; et al. Driver Fusions and Their Implications in the Development and Treatment of Human Cancers. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 227–238 e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.E.; Dodi, I.A.; Hill, S.C.; Lill, J.R.; Aubert, G.; Macintyre, A.R.; Rojas, J.; Bourdon, A.; Bonner, P.L.; Wang, L.; et al. Direct evidence that leukemic cells present HLA-associated immunogenic peptides derived from the BCR-ABL b3a2 fusion protein. Blood 2001, 98, 2887–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ren, Z.; Qi, J.; Qi, E.; Zhao, X.; Li, G.; Yu, T. Gene fusion detection in long-read transcriptome sequencing data with GFvoter. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Tan, Z.; Song, Y.; Human Genome Structural Variation Consortium; Chen, H.; Chong, Z. Gene Fusion Detection and Characterization in Long-Read Cancer Transcriptome Sequencing Data with FusionSeeker. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, N.M.; Chen, Y.; Sadras, T.; Ryland, G.L.; Blombery, P.; Ekert, P.G.; Goke, J.; Oshlack, A. JAFFAL: Detecting fusion genes with long-read transcriptome sequencing. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilf, N.; Kuttruff-Coqui, S.; Frenzel, K.; Bukur, V.; Stevanovic, S.; Gouttefangeas, C.; Platten, M.; Tabatabai, G.; Dutoit, V.; van der Burg, S.H.; et al. Actively personalized vaccination trial for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Nature 2019, 565, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akondy, R.S.; Johnson, P.L.; Nakaya, H.I.; Edupuganti, S.; Mulligan, M.J.; Lawson, B.; Miller, J.D.; Pulendran, B.; Antia, R.; Ahmed, R. Initial viral load determines the magnitude of the human CD8 T cell response to yellow fever vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3050–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Muik, A.; Vogler, I.; Derhovanessian, E.; Kranz, L.M.; Vormehr, M.; Quandt, J.; Bidmon, N.; Ulges, A.; Baum, A.; et al. BNT162b2 vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and poly-specific T cells in humans. Nature 2021, 595, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikis, P.D.; Ishii, K.J.; Schliehe, C. Challenges in developing personalized neoantigen cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrail, D.J.; Pilie, P.G.; Rashid, N.U.; Voorwerk, L.; Slagter, M.; Kok, M.; Jonasch, E.; Khasraw, M.; Heimberger, A.B.; Lim, B.; et al. High tumor mutation burden fails to predict immune checkpoint blockade response across all cancer types. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurjao, C.; Tsukrov, D.; Imakaev, M.; Luquette, L.J.; Mirny, L.A. Is tumor mutational burden predictive of response to immunotherapy? Elife 2024, 12, RP87465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, V. Existence and Nature of Dark Matter in the Universe. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 1987, 25, 425–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.W.; Yi, Z.; Weissman, J.S.; Chen, J. The dark proteome: Translation from noncanonical open reading frames. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, E.S. Initial impact of the sequencing of the human genome. Nature 2011, 470, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, C.; Muller, M.; Pak, H.; Harnett, D.; Huber, F.; Grun, D.; Leleu, M.; Auger, A.; Arnaud, M.; Stevenson, B.J.; et al. Integrated proteogenomic deep sequencing and analytics accurately identify non-canonical peptides in tumor immunopeptidomes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouspenskaia, T.; Law, T.; Clauser, K.R.; Klaeger, S.; Sarkizova, S.; Aguet, F.; Li, B.; Christian, E.; Knisbacher, B.A.; Le, P.M.; et al. Unannotated proteins expand the MHC-I-restricted immunopeptidome in cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laumont, C.M.; Daouda, T.; Laverdure, J.P.; Bonneil, E.; Caron-Lizotte, O.; Hardy, M.P.; Granados, D.P.; Durette, C.; Lemieux, S.; Thibault, P.; et al. Global proteogenomic analysis of human MHC class I-associated peptides derived from non-canonical reading frames. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Mao, M.; Lv, Y.; Yang, Y.; He, W.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Al Abo, M.; Freedman, J.A.; et al. A widespread length-dependent splicing dysregulation in cancer. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabn9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.D.; Lee, N.H. Aberrant RNA Splicing in Cancer and Drug Resistance. Cancers 2018, 10, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Aifantis, I. RNA Splicing and Cancer. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Yong, L. Systematic profiling of alternative splicing signature reveals prognostic predictor for ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 148, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, B.; Nie, J.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, H. The Roles of Alternative Splicing in Tumor-immune Cell Interactions. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2020, 20, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasinghe, R.G.; Cao, S.; Gao, Q.; Wendl, M.C.; Vo, N.S.; Reynolds, S.M.; Zhao, Y.; Climente-Gonzalez, H.; Chai, S.; Wang, F.; et al. Systematic Analysis of Splice-Site-Creating Mutations in Cancer. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 270–281.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apcher, S.; Daskalogianni, C.; Lejeune, F.; Manoury, B.; Imhoos, G.; Heslop, L.; Fahraeus, R. Major source of antigenic peptides for the MHC class I pathway is produced during the pioneer round of mRNA translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11572–11577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, A.; Kervestin, S.; Jacobson, A. NMD: At the crossroads between translation termination and ribosome recycling. Biochimie 2015, 114, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Cesarano, A.; Bombaci, G.; Reiter, J.L.; Yu, C.Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zaid, M.A.; Huang, K.; Lu, X.; et al. Intron retention-induced neoantigen load correlates with unfavorable prognosis in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 2021, 40, 6130–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahles, A.; Lehmann, K.V.; Toussaint, N.C.; Huser, M.; Stark, S.G.; Sachsenberg, T.; Stegle, O.; Kohlbacher, O.; Sander, C.; The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Alternative Splicing Across Tumors from 8705 Patients. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 211–224.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.K.; Maden, S.K.; Weeder, B.R.; Thompson, R.F.; Nellore, A. Putatively cancer-specific exon-exon junctions are shared across patients and present in developmental and other non-cancer cells. NAR Cancer 2020, 2, zcaa001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramany, A.S.; Schieffer, K.M.; Lee, K.; Cottrell, C.E.; Wang, P.Y.; Mardis, E.R.; Cripe, T.P.; Chandler, D.S. Alternative RNA splicing defects in pediatric cancers: New insights in tumorigenesis and potential therapeutic vulnerabilities. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.N.; Choi, P.S.; de Waal, L.; Sharifnia, T.; Imielinski, M.; Saksena, G.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Sivachenko, A.; Rosenberg, M.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. A pan-cancer analysis of transcriptome changes associated with somatic mutations in U2AF1 reveals commonly altered splicing events. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsafadi, S.; Houy, A.; Battistella, A.; Popova, T.; Wassef, M.; Henry, E.; Tirode, F.; Constantinou, A.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Roman-Roman, S.; et al. Cancer-associated SF3B1 mutations affect alternative splicing by promoting alternative branchpoint usage. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigot, J.; Lalanne, A.I.; Lucibello, F.; Gueguen, P.; Houy, A.; Dayot, S.; Ganier, O.; Gilet, J.; Tosello, J.; Nemati, F.; et al. Splicing Patterns in SF3B1-Mutated Uveal Melanoma Generate Shared Immunogenic Tumor-Specific Neoepitopes. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kesel, J.; Fijalkowski, I.; Taylor, J.; Ntziachristos, P. Splicing dysregulation in human hematologic malignancies: Beyond splicing mutations. Trends Immunol. 2022, 43, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Cuevas, M.V.; Hardy, M.P.; Holly, J.; Bonneil, E.; Durette, C.; Courcelles, M.; Lanoix, J.; Cote, C.; Staudt, L.M.; Lemieux, S.; et al. Most non-canonical proteins uniquely populate the proteome or immunopeptidome. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, A.C.; Margolis, C.A.; Pimentel, H.; He, M.X.; Miao, D.; Adeegbe, D.; Fugmann, T.; Wong, K.K.; Van Allen, E.M. Intron retention is a source of neoepitopes in cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 1056–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Han, Z.; Ma, D. Immune checkpoint therapy for solid tumours: Clinical dilemmas and future trends. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazak, L.; Haviv, A.; Barak, M.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Deng, P.; Zhang, R.; Isaacs, F.J.; Rechavi, G.; Li, J.B.; Eisenberg, E.; et al. A-to-I RNA editing occurs at over a hundred million genomic sites, located in a majority of human genes. Genome Res. 2014, 24, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Aroya, S.; Levanon, E.Y. A-to-I RNA Editing: An Overlooked Source of Cancer Mutations. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 789–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlotti, A.; Sadacca, B.; Arribas, Y.A.; Ngoma, M.; Burbage, M.; Goudot, C.; Houy, A.; Rocañín-Arjó, A.; Lalanne, A.; Seguin-Givelet, A. Noncanonical splicing junctions between exons and transposable elements represent a source of immunogenic recurrent neo-antigens in patients with lung cancer. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, eabm6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Yu, Y.V.; Jin, Y.N. Non-canonical translation in cancer: Significance and therapeutic potential of non-canonical ORFs, m(6)A-modification, and circular RNAs. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tano, K.; Akimitsu, N. Long non-coding RNAs in cancer progression. Front. Genet. 2012, 3, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, A.; Bohlen, J.; Teleman, A.A. Translation acrobatics: How cancer cells exploit alternate modes of translational initiation. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, EMBR201845947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspden, J.L.; Eyre-Walker, Y.C.; Phillips, R.J.; Amin, U.; Mumtaz, M.A.; Brocard, M.; Couso, J.P. Extensive translation of small Open Reading Frames revealed by Poly-Ribo-Seq. eLife 2014, 3, e03528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.J.; Leng, R.X.; Fan, Y.G.; Pan, H.F.; Ye, D.Q. Translation of noncoding RNAs: Focus on lncRNAs, pri-miRNAs, and circRNAs. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 361, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truitt, M.L.; Ruggero, D. New frontiers in translational control of the cancer genome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.; Mahmood, N.; Tahmasebi, S.; Sonenberg, N. eIF4F-mediated dysregulation of mRNA translation in cancer. RNA 2025, 31, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingolia, N.T.; Brar, G.A.; Rouskin, S.; McGeachy, A.M.; Weissman, J.S. The ribosome profiling strategy for monitoring translation in vivo by deep sequencing of ribosome-protected mRNA fragments. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 1534–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingolia, N.T. Ribosome Footprint Profiling of Translation throughout the Genome. Cell 2016, 165, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappinelli, K.B.; Strissel, P.L.; Desrichard, A.; Li, H.; Henke, C.; Akman, B.; Hein, A.; Rote, N.S.; Cope, L.M.; Snyder, A.; et al. Inhibiting DNA Methylation Causes an Interferon Response in Cancer via dsRNA Including Endogenous Retroviruses. Cell 2015, 162, 974–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.K.; Ramakrishna, W. Transposons: Unexpected players in cancer. Gene 2022, 808, 145975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Rose, C.M.; Cass, A.A.; Williams, A.G.; Darwish, M.; Lianoglou, S.; Haverty, P.M.; Tong, A.J.; Blanchette, C.; Albert, M.L.; et al. Transposable element expression in tumors is associated with immune infiltration and increased antigenicity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Jr.; Ahmad, S.F.; Xu, J. Regulation and function of transposable elements in cancer genomes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanciano, S.; Philippe, C.; Sarkar, A.; Pratella, D.; Domrane, C.; Doucet, A.J.; van Essen, D.; Saccani, S.; Ferry, L.; Defossez, P.A.; et al. Locus-level L1 DNA methylation profiling reveals the epigenetic and transcriptional interplay between L1s and their integration sites. Cell Genom. 2024, 4, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaian, A.; Mager, D.L. Endogenous retroviral promoter exaptation in human cancer. Mob. DNA 2016, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodic, N.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, R.; Zampella, J.; Dai, L.; Taylor, M.S.; Hruban, R.H.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C.A.; Maitra, A.; Torbenson, M.S.; et al. Long interspersed element-1 protein expression is a hallmark of many human cancers. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.S.; Wu, C.; Fridy, P.C.; Zhang, S.J.; Senussi, Y.; Wolters, J.C.; Cajuso, T.; Cheng, W.C.; Heaps, J.D.; Miller, B.D.; et al. Ultrasensitive Detection of Circulating LINE-1 ORF1p as a Specific Multicancer Biomarker. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 2532–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaventura, P.; Page, A.; Tabone, O.; Estornes, Y.; Mutez, V.; Delles, M.; Moran, S.; Dubois, C.; Richard, T.; Lacourrege, M.; et al. HERV-derived epitopes represent new targets for T-cell-based immunotherapies in ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e010099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garde, C.; Pavlidis, M.A.; Garces, P.; Lange, E.J.; Ramarathinam, S.H.; Sokac, M.; Pandey, K.; Faridi, P.; Ahrenfeldt, J.; Chung, S.; et al. Endogenous viral elements constitute a complementary source of antigens for personalized cancer vaccines. NPJ Vaccines 2025, 10, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivancevic, A.; Simpson, D.M.; Joyner, O.M.; Bagby, S.M.; Nguyen, L.L.; Bitler, B.G.; Pitts, T.M.; Chuong, E.B. Endogenous retroviruses mediate transcriptional rewiring in response to oncogenic signaling in colorectal cancer. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, F.; Cobbold, M.; Zarling, A.L.; Salim, M.; Barrett-Wilt, G.A.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D.F.; Engelhard, V.H.; Willcox, B.E. Phosphorylation-dependent interaction between antigenic peptides and MHC class I: A molecular basis for the presentation of transformed self. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigneron, N.; Stroobant, V.; Ferrari, V.; Abi Habib, J.; Van den Eynde, B.J. Production of spliced peptides by the proteasome. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 113, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, A.; Relvas-Santos, M.; Azevedo, R.; Santos, L.L.; Ferreira, J.A. Protein Glycosylation and Tumor Microenvironment Alterations Driving Cancer Hallmarks. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbold, M.; De La Pena, H.; Norris, A.; Polefrone, J.M.; Qian, J.; English, A.M.; Cummings, K.L.; Penny, S.; Turner, J.E.; Cottine, J.; et al. MHC class I-associated phosphopeptides are the targets of memory-like immunity in leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 203ra125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarling, A.L.; Polefrone, J.M.; Evans, A.M.; Mikesh, L.M.; Shabanowitz, J.; Lewis, S.T.; Engelhard, V.H.; Hunt, D.F. Identification of class I MHC-associated phosphopeptides as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 14889–14894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaker, S.A.; Penny, S.A.; Steadman, L.G.; Myers, P.T.; Loke, J.C.; Raghavan, M.; Bai, D.L.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D.F.; Cobbold, M. Identification of Glycopeptides as Posttranslationally Modified Neoantigens in Leukemia. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepe, J.; Marino, F.; Sidney, J.; Jeko, A.; Bunting, D.E.; Sette, A.; Kloetzel, P.M.; Stumpf, M.P.; Heck, A.J.; Mishto, M. A large fraction of HLA class I ligands are proteasome-generated spliced peptides. Science 2016, 354, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Bassani-Sternberg, M. Current perspectives on mass spectrometry-based immunopeptidomics: The computational angle to tumor antigen discovery. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e007073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingolia, N.T.; Brar, G.A.; Stern-Ginossar, N.; Harris, M.S.; Talhouarne, G.J.; Jackson, S.E.; Wills, M.R.; Weissman, J.S. Ribosome profiling reveals pervasive translation outside of annotated protein-coding genes. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedran, G.; Gasser, H.C.; Weke, K.; Wang, T.; Bedran, D.; Laird, A.; Battail, C.; Zanzotto, F.M.; Pesquita, C.; Axelson, H.; et al. The Immunopeptidome from a Genomic Perspective: Establishing the Noncanonical Landscape of MHC Class I-Associated Peptides. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2023, 11, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreper, D.; Klaeger, S.; Jhunjhunwala, S.; Delamarre, L. The peptide woods are lovely, dark and deep: Hunting for novel cancer antigens. Semin. Immunol. 2023, 67, 101758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.; Banskota, N.; Gorospe, M.; De, S. Comprehensive Overview of Computational Tools for Alternative Splicing Analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2025, 16, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.; Breese, M.R.; Hao, Y.; Edenberg, H.J.; Li, L.; Skaar, T.C.; Liu, Y. Alt Event Finder: A tool for extracting alternative splicing events from RNA-seq data. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Park, J.W.; Lu, Z.X.; Lin, L.; Henry, M.D.; Wu, Y.N.; Zhou, Q.; Xing, Y. rMATS: Robust and flexible detection of differential alternative splicing from replicate RNA-Seq data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E5593–E5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero-Garcia, J.; Barrera, A.; Gazzara, M.R.; Gonzalez-Vallinas, J.; Lahens, N.F.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Lynch, K.W.; Barash, Y. A new view of transcriptome complexity and regulation through the lens of local splicing variations. eLife 2016, 5, e11752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halperin, R.F.; Hegde, A.; Lang, J.D.; Raupach, E.A.; Group, C.R.R.; Legendre, C.; Liang, W.S.; LoRusso, P.M.; Sekulic, A.; Sosman, J.A.; et al. Improved methods for RNAseq-based alternative splicing analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertes, C.; Scheller, I.F.; Yepez, V.A.; Celik, M.H.; Liang, Y.; Kremer, L.S.; Gusic, M.; Prokisch, H.; Gagneur, J. Detection of aberrant splicing events in RNA-seq data using FRASER. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Kingsford, C. Accurate assembly of transcripts through phase-preserving graph decomposition. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1167–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, S.L.; Su, S.; Dong, X.; Zappia, L.; Ritchie, M.E.; Gouil, Q. Opportunities and challenges in long-read sequencing data analysis. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.P.; Tseng, E.; Salamov, A.; Zhang, J.; Meng, X.; Zhao, Z.; Kang, D.; Underwood, J.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Figueroa, M.; et al. Widespread Polycistronic Transcripts in Fungi Revealed by Single-Molecule mRNA Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, L.H.; Shao, M.; Kingsford, C. Quantifying the benefit offered by transcript assembly with Scallop-LR on single-molecule long reads. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.D.; Soulette, C.M.; van Baren, M.J.; Hart, K.; Hrabeta-Robinson, E.; Wu, C.J.; Brooks, A.N. Full-length transcript characterization of SF3B1 mutation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals downregulation of retained introns. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, R.; Gao, D.; Thomas, A.; Singh, B.; Au, A.; Wong, J.J.; Bomane, A.; Cosson, B.; Eyras, E.; Rasko, J.E.; et al. IRFinder: Assessing the impact of intron retention on mammalian gene expression. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F. Accurate quantification of circular RNAs identifies extensive circular isoform switching events. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, G.T. Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: Multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science 2015, 348, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N.; Weinstein, J.N.; Collisson, E.A.; Mills, G.B.; Shaw, K.R.; Ozenberger, B.A.; Ellrott, K.; Shmulevich, I.; Sander, C.; Stuart, J.M. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Li, W.; Smith, A.D. Accurate detection of short and long active ORFs using Ribo-seq data. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 2053–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Wang, S.H.; Shim, H.; Harpak, A.; Li, Y.I.; Engelmann, B.; Stephens, M.; Gilad, Y.; Pritchard, J.K. Thousands of novel translated open reading frames in humans inferred by ribosome footprint profiling. eLife 2016, 5, e13328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Song, R.; Regev, A.; Struhl, K. Many lncRNAs, 5′UTRs, and pseudogenes are translated and some are likely to express functional proteins. eLife 2015, 4, e08890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erhard, F.; Halenius, A.; Zimmermann, C.; L’Hernault, A.; Kowalewski, D.J.; Weekes, M.P.; Stevanovic, S.; Zimmer, R.; Dolken, L. Improved Ribo-seq enables identification of cryptic translation events. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelin, J.G.; Keskin, D.B.; Sarkizova, S.; Hartigan, C.R.; Zhang, W.; Sidney, J.; Stevens, J.; Lane, W.; Zhang, G.L.; Eisenhaure, T.M.; et al. Mass Spectrometry Profiling of HLA-Associated Peptidomes in Mono-allelic Cells Enables More Accurate Epitope Prediction. Immunity 2017, 46, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Schreiber, R.D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 2015, 348, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczak, W.; Carr, S.M.; Liu, G.; Munro, S.; Nicastri, A.; Lee, L.N.; Hutchings, C.; Ternette, N.; Klenerman, P.; Kanapin, A.; et al. Long non-coding RNA-derived peptides are immunogenic and drive a potent anti-tumour response. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R.; Cadieux, E.L.; Salgado, R.; Bakir, M.A.; Moore, D.A.; Hiley, C.T.; Lund, T.; Tanic, M.; Reading, J.L.; Joshi, K.; et al. Neoantigen-directed immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Nature 2019, 567, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Rabella, M.; Garcia-Garijo, A.; Palomero, J.; Yuste-Estevanez, A.; Erhard, F.; Farriol-Duran, R.; Martin-Liberal, J.; Ochoa-de-Olza, M.; Matos, I.; Gartner, J.J.; et al. Exploring the Immunogenicity of Noncanonical HLA-I Tumor Ligands Identified through Proteogenomics. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2250–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, S.; Schmitz, J.; Loffler, M.W.; Ghosh, M.; Rammensee, H.G.; Olshvang, E.; Markel, M.; Mockel-Tenbrinck, N.; Dzionek, A.; Krake, S.; et al. T cells of colorectal cancer patients’ stimulated by neoantigenic and cryptic peptides better recognize autologous tumor cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, Q.; Stroup, E.K.; Wang, S.; Ji, Z. Widespread stable noncanonical peptides identified by integrated analyses of ribosome profiling and ORF features. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGranahan, N.; Swanton, C. Clonal Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution: Past, Present, and the Future. Cell 2017, 168, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rospo, G.; Chila, R.; Matafora, V.; Basso, V.; Lamba, S.; Bartolini, A.; Bachi, A.; Di Nicolantonio, F.; Mondino, A.; Germano, G.; et al. Non-canonical antigens are the largest fraction of peptides presented by MHC class I in mismatch repair deficient murine colorectal cancer. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efremova, M.; Rieder, D.; Klepsch, V.; Charoentong, P.; Finotello, F.; Hackl, H.; Hermann-Kleiter, N.; Lower, M.; Baier, G.; Krogsdam, A.; et al. Targeting immune checkpoints potentiates immunoediting and changes the dynamics of tumor evolution. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcu, A.; Bichmann, L.; Kuchenbecker, L.; Kowalewski, D.J.; Freudenmann, L.K.; Backert, L.; Muhlenbruch, L.; Szolek, A.; Lubke, M.; Wagner, P.; et al. HLA Ligand Atlas: A benign reference of HLA-presented peptides to improve T-cell-based cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Liao, Y.; Wen, B.; Li, K.; Dou, Y.; Savage, S.R.; Zhang, B. caAtlas: An immunopeptidome atlas of human cancer. iScience 2021, 24, 103107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trolle, T.; Nielsen, M. NetTepi: An integrated method for the prediction of T cell epitopes. Immunogenetics 2014, 66, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.; Smith, A.R.; Magnin, M.; Racle, J.; Devlin, J.R.; Bobisse, S.; Cesbron, J.; Bonnet, V.; Carmona, S.J.; Huber, F.; et al. Prediction of neo-epitope immunogenicity reveals TCR recognition determinants and provides insight into immunoediting. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurtz, V.; Paul, S.; Andreatta, M.; Marcatili, P.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.0: Improved Peptide-MHC Class I Interaction Predictions Integrating Eluted Ligand and Peptide Binding Affinity Data. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 3360–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulashevska, A.; Nacsa, Z.; Lang, F.; Braun, M.; Machyna, M.; Diken, M.; Childs, L.; Konig, R. Artificial intelligence and neoantigens: Paving the path for precision cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1394003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani-Sternberg, M.; Gfeller, D. Unsupervised HLA Peptidome Deconvolution Improves Ligand Prediction Accuracy and Predicts Cooperative Effects in Peptide-HLA Interactions. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 2492–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.K.; van Buuren, M.M.; Dang, K.K.; Hubbard-Lucey, V.M.; Sheehan, K.C.F.; Campbell, K.M.; Lamb, A.; Ward, J.P.; Sidney, J.; Blazquez, A.B.; et al. Key Parameters of Tumor Epitope Immunogenicity Revealed Through a Consortium Approach Improve Neoantigen Prediction. Cell 2020, 183, 818–834.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, W.; Sun, Q.; Xu, B.; Wang, R. Towards the Prediction of Responses to Cancer Immunotherapy: A Multi-Omics Review. Life 2025, 15, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloudina, A.; Le Chevalier, F.; Authie, P.; Charneau, P.; Majlessi, L. Shared neoantigens for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2025, 33, 200978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Saddawi-Konefka, R.; Clubb, L.M.; Tang, S.; Wu, D.; Mukherjee, S.; Sahni, S.; Dhruba, S.R.; Yang, X.; Patiyal, S.; et al. Longitudinal liquid biopsy identifies an early predictive biomarker of immune checkpoint blockade response in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Gong, M.; Zeng, M.; Leng, F.; Lv, D.; Guo, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Lin, Q.; Jing, J.; et al. Immunopeptidomics-guided discovery and characterization of neoantigens for personalized cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Ref. | Tumour Type/Model | Non-Canonical | Main Approach | Immunological Validation | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laumont et al. [17] | Murine (CT26 and EL4), human samples | Introns, UTRs, pseudogenes | Bioinformatic + MS | ELISpot, tetramers, tumour rejection |

|

| Barczak et al. [145] | Murine (CT26) and human (HCT116) | Small ORF in lncRNAs | Transcriptomic + translatomic + immunopeptidomics | Ex vivo–loaded DCs; ChAdOx1/MVA viral vector vaccination |

|

| Raja et al. [20] | Human cervical cancer | lncRNAs and pseudogenes | Immunopeptidomics + in silico prioritisation | Autologous T-cell assays |

|

| Apavaloaei et al. [45] | Human melanoma, NSCLC | Broad non-canonical regions | RNA-seq + MS | Autologous PBMC and TIL assays |

|

| Lozano-Rabellá et al. [147] | Melanoma, gynecologic, and head and neck cancer | 5’UTR, off-frame, and ncRNA | RNA-seq/LC/MS-MS | Donor PBMC and TIL functional assays |

|

| Ely et al. [18] | Human pancreatic cancer organoids + bulk tumours | lncRNAs, 5′ or 3′ UTRs, alternative ORFs | proteogenomic and high-depth immunopeptidomics | ex vivo T-cell priming, expansion, tetramers, killing assays |

|

| Schwarz et al. [148] | microsatellite-instable colorectal cancer | Non-canonical ORFs | Immunopeptidomics | IFNγ ELISPot, Immunophenotyping |

|

| Merlotti et al. [90] | NSCLC (TCGA transcriptomes + tumour samples) | JETs (junction-encoded transcripts) | Transcriptomics + immunopeptidomics | CD8+ T-cell expansion, IFN-γ, granzyme B, tumour lysis |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rwandamuriye, F.X.; Redwood, A.J.; Creaney, J.; Robinson, B.W.S. Hidden Targets in Cancer Immunotherapy: The Potential of “Dark Matter” Neoantigens. Vaccines 2026, 14, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010104

Rwandamuriye FX, Redwood AJ, Creaney J, Robinson BWS. Hidden Targets in Cancer Immunotherapy: The Potential of “Dark Matter” Neoantigens. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleRwandamuriye, Francois Xavier, Alec J. Redwood, Jenette Creaney, and Bruce W. S. Robinson. 2026. "Hidden Targets in Cancer Immunotherapy: The Potential of “Dark Matter” Neoantigens" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010104

APA StyleRwandamuriye, F. X., Redwood, A. J., Creaney, J., & Robinson, B. W. S. (2026). Hidden Targets in Cancer Immunotherapy: The Potential of “Dark Matter” Neoantigens. Vaccines, 14(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010104