Design and Immune Profile of Multi-Epitope Synthetic Antigen Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2: An In Silico and In Vivo Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Sequence Retrieval

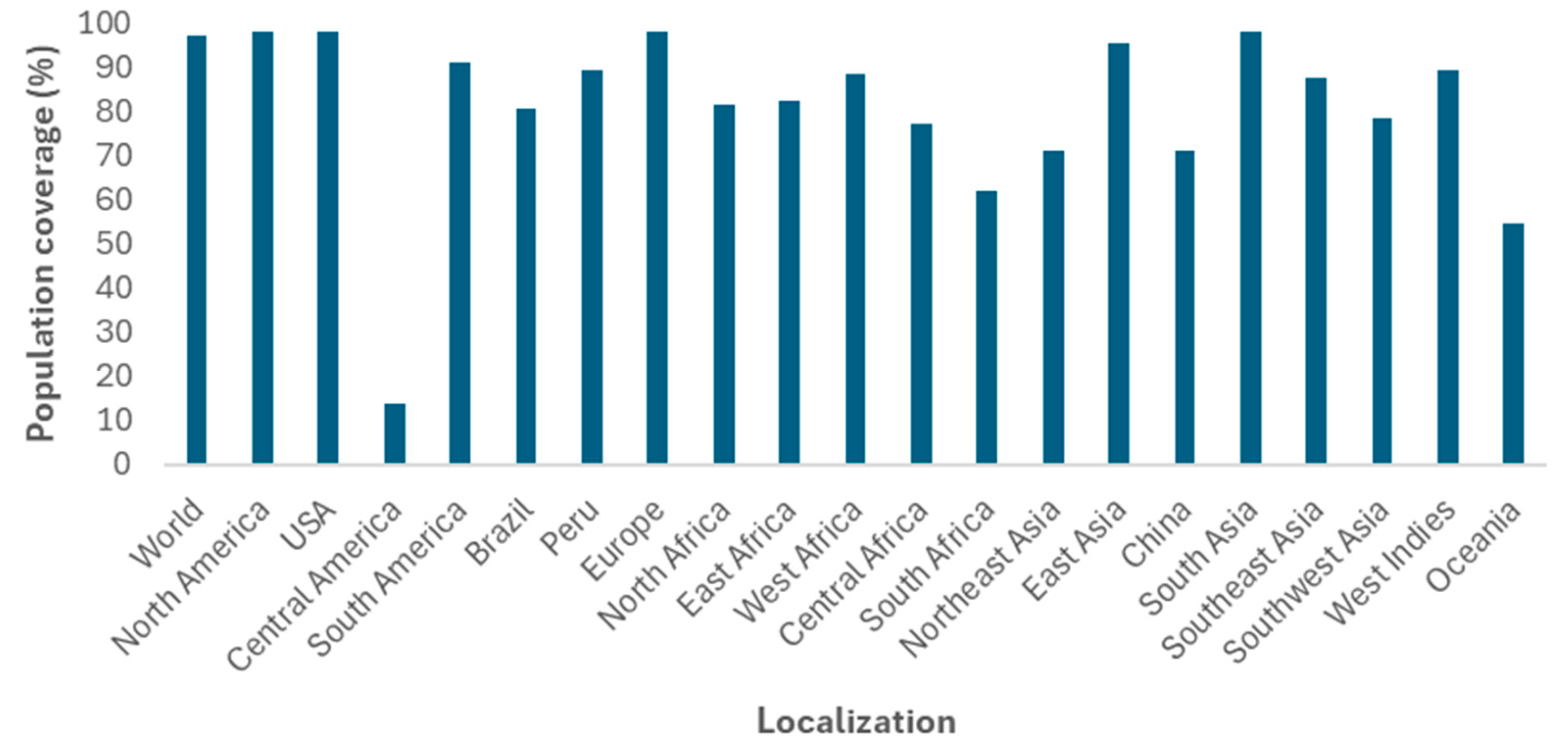

2.2. Epitope Prediction and Analysis

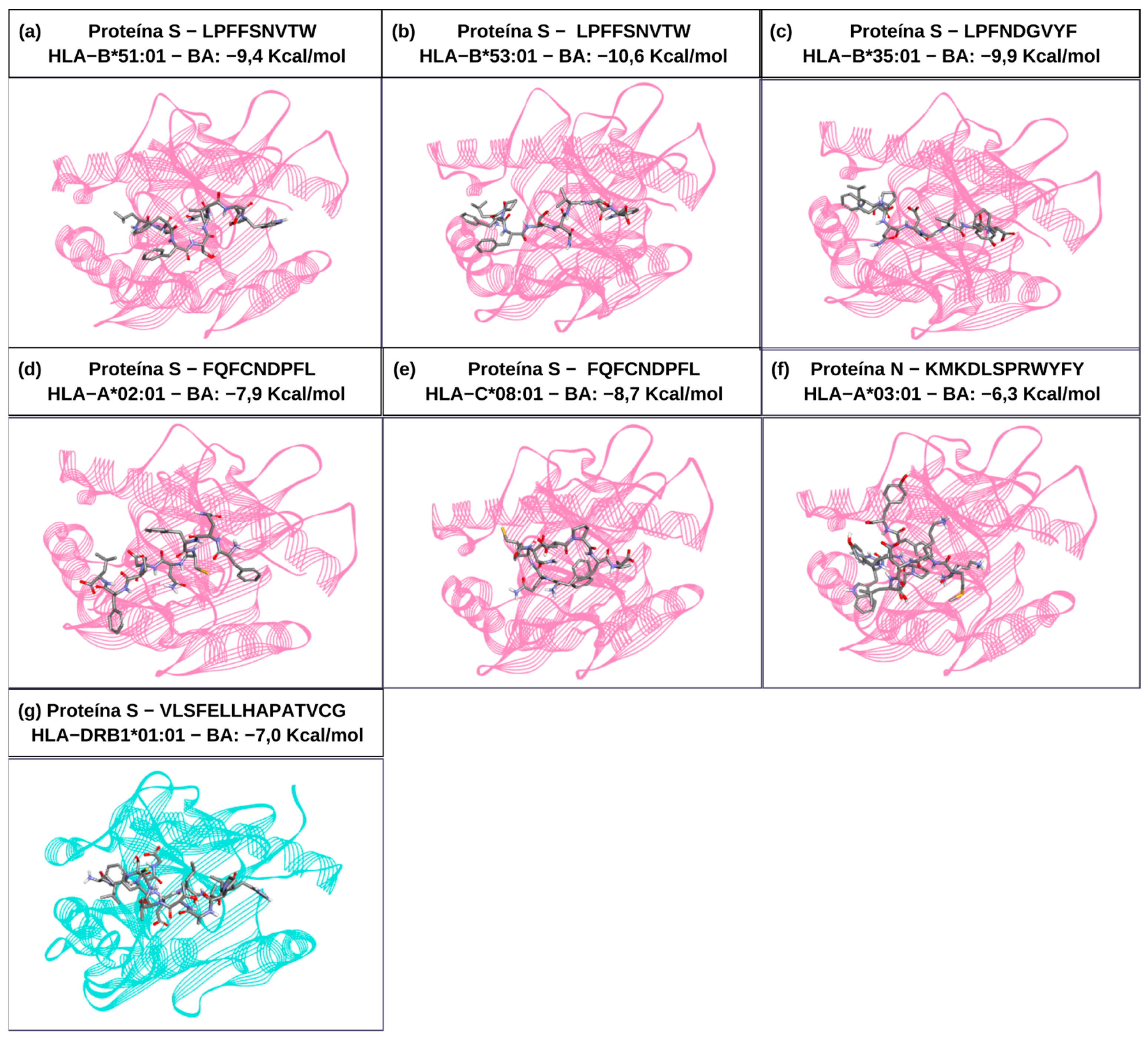

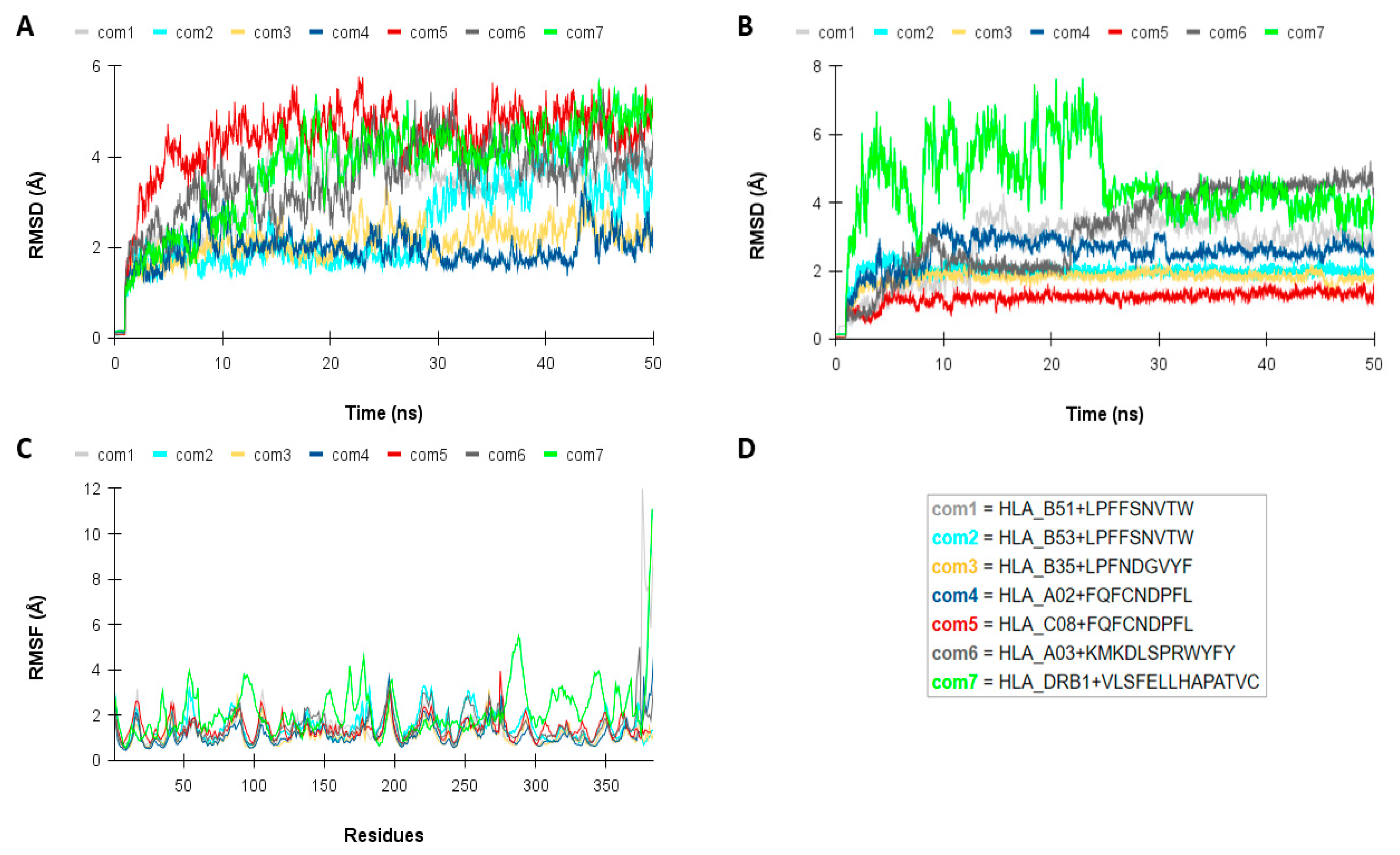

2.3. Molecular Interaction Analysis Among the TCD8+ and TCD4+ Epitopes with HLAs Alleles

2.4. Multi-Epitope Vaccine Antigen Design and Antigenicity, Allergenicity, Cross-Reactivity, Solubility, and Physicochemical Properties

2.5. Molecular Docking of Multi-Epitope Vaccine and Toll-like Receptors (TLRs)

2.6. DNA Vaccine Preparation

2.7. Transfection and Expression Analysis After Cell Culture

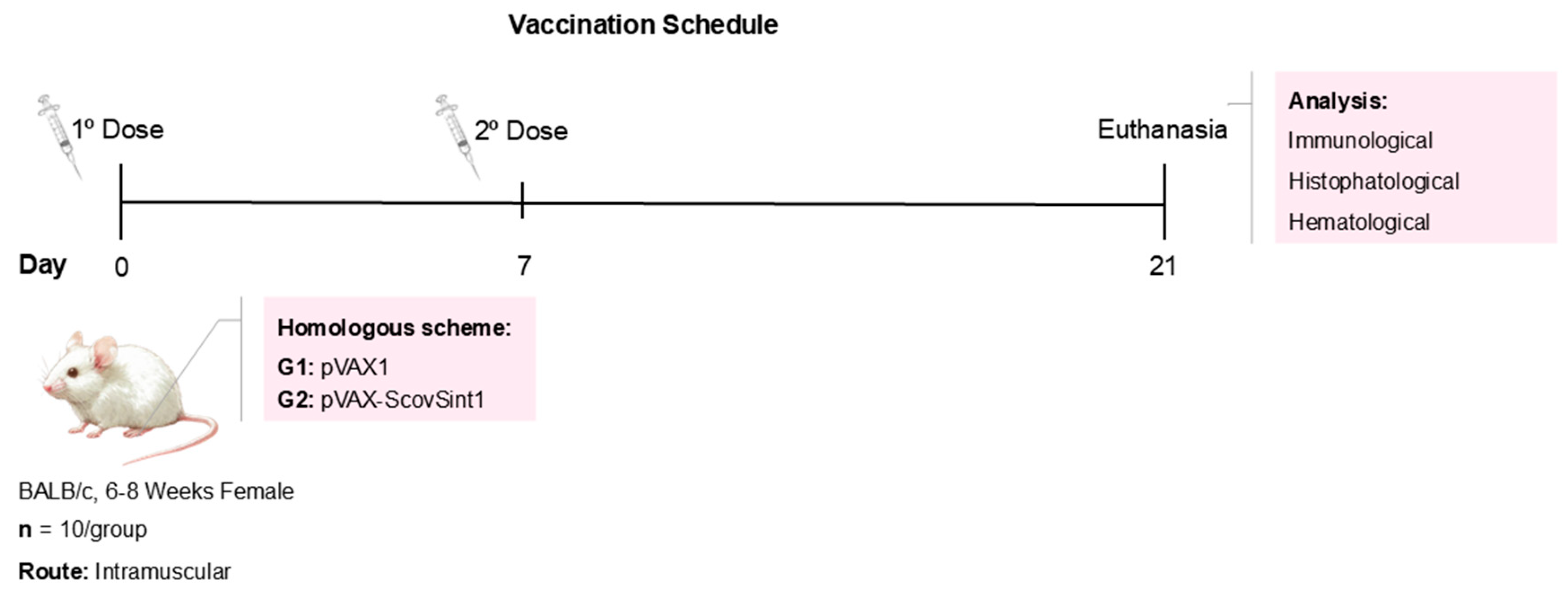

2.8. Immunization Protocols and Characterization of Experimental Groups

2.9. Immunological Investigation

2.10. Histopathological Investigation

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Selection and Analysis of T- and B-Cell Epitopes

3.2. Multi-Epitope Design and Analysis

3.3. ScovSint1 Structure Modeling and Refinement

3.4. Molecular Docking of ScovSint1 with TLRs and Immune Simulations

3.5. Cloning and In Vivo Vaccine Evaluation

3.5.1. Obtaining the Expression Vector

3.5.2. Checking the Expression of the Vaccine Antigen, Scovsint1

3.5.3. Immunological Analysis

3.6. Histopathological Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, W.-H.; Strych, U.; Hotez, P.J.; Bottazzi, M.E. The SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Pipeline: An Overview. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2020, 7, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, H.M.; Mirza, M.U.; Ahmad, M.A.; Saleem, M.; Froeyen, M.; Ahmad, S.; Gul, R.; Alghamdi, H.A.; Aslam, M.S.; Sajjad, M.; et al. A Putative Prophylactic Solution for COVID-19: Development of Novel Multiepitope Vaccine Candidate against SARS-COV-2 by Comprehensive Immunoinformatic and Molecular Modelling Approach. Biology 2020, 9, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global Market Study: HPV. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/311275 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Krammer, F. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines in Development. Nature 2020, 586, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Entry into Cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Chu, Z.; Yu, F.; Zha, Y. Contriving Multi-Epitope Subunit of Vaccine for COVID-19: Immunoinformatics Approaches. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayatkhani, M.; Hasaniazad, M.; Faezi, S.; Gouklani, H.; Davoodian, P.; Ahmadi, N.; Einakian, M.A.; Karmostaji, A.; Ahmadi, K. Reverse Vaccinology Approach to Design a Novel Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate against COVID-19: An in Silico Study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 2857–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, A.; Shahid, F.; Butt, T.T.; Awan, F.M.; Ali, A.; Malik, A. Designing Multi-Epitope Vaccines to Combat Emerging Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) by Employing Immuno-Informatics Approach. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, E.K.; Ajayi, A.F.; Ariyo, O.E.; Onile, S.O.; Jimah, E.M.; Ezediuno, L.O.; Adebayo, O.I.; Adebayo, E.T.; Odeyemi, A.N.; Oyeleke, M.O.; et al. Exploration of Surface Glycoprotein to Design Multi-Epitope Vaccine for the Prevention of COVID-19. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2020, 21, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanami, S.; Zandi, M.; Pourhossein, B.; Mobini, G.-R.; Safaei, M.; Abed, A.; Arvejeh, P.M.; Chermahini, F.A.; Alizadeh, M. Design of a Multi-Epitope Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 Using Immunoinformatics Approach. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Jakhar, R.; Sehrawat, N. Designing Spike Protein (S-Protein) Based Multi-Epitope Peptide Vaccine against SARS COVID-19 by Immunoinformatics. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- IEDB. Available online: https://www.iedb.org (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Rahman, M.S.; Hoque, M.N.; Islam, M.R.; Akter, S.; Rubayet-Ul-Alam, A.; Siddique, M.A.; Saha, O.; Rahaman, M.d.M.; Sultana, M.; Crandall, K.A.; et al. Epitope-Based Chimeric Peptide Vaccine Design against S, M and E Proteins of SARS-CoV-2 Etiologic Agent of Global Pandemic COVID-19: An in Silico Approach. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Class I Immunogenecity. Available online: http://tools.iedb.org/immunogenicity/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- ToxinPred. Available online: https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/toxinpred/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Park, T.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, H.G.; Jun, S.; Kim, S.I.; Kim, B.T.; Park, E.C.; Park, D. Spike Protein Binding Prediction with Neutralizing Antibodies of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epitope Conservancy Analysis. Available online: http://tools.iedb.org/conservancy/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Population Coverage. Available online: http://tools.iedb.org/population/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Lamiable, A.; Thévenet, P.; Rey, J.; Vavrusa, M.; Derreumaux, P.; Tufféry, P. PEP-FOLD3: Faster de Novo Structure Prediction for Linear Peptides in Solution and in Complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempel, J.E. Chemical Biology: Methods and Protocols; Williams, C.H., Hong, C.C., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4939-2268-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dassault Systèmes Biovia Discovery Studio Visualizer (BIOVIA) V21.1.0 (Version 21.1.0). Available online: https://www.3ds.com/products-services/biovia/products/molecular-modeling-simulation/biovia-discovery-studio/ (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Phillips, J.C.; Braun, R.; Wang, W.; Gumbart, J.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Villa, E.; Chipot, C.; Skeel, R.D.; Kalé, L.; Schulten, K. Scalable Molecular Dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; MacKerell, A.D. CHARMM36 All-Atom Additive Protein Force Field: Validation Based on Comparison to NMR Data. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A Web-based Graphical User Interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.K.; Ojha, R.; Aathmanathan, V.S.; Krishnan, M.; Prajapati, V.K. Immunoinformatics Approaches to Design a Novel Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccine against HIV Infection. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2262–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, B.; Crimi, C.; Newman, M.; Higashimoto, Y.; Appella, E.; Sidney, J.; Sette, A. A Rational Strategy to Design Multiepitope Immunogens Based on Multiple Th Lymphocyte Epitopes. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 5499–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezafat, N.; Ghasemi, Y.; Javadi, G.; Khoshnoud, M.J.; Omidinia, E. A Novel Multi-Epitope Peptide Vaccine against Cancer: An in Silico Approach. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 349, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezafat, N.; Eslami, M.; Negahdaripour, M.; Rahbar, M.R.; Ghasemi, Y. Designing an Efficient Multi-Epitope Oral Vaccine against Helicobacter Pylori Using Immunoinformatics and Structural Vaccinology Approaches. Mol. BioSyst. 2017, 13, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alphafold. Available online: https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Galaxy Web. Available online: http://galaxy.seoklab.org (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- PDB Sum. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/pdbsum/Generate.html (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Doytchinova, I.A.; Flower, D.R. VaxiJen: A Server for Prediction of Protective Antigens, Tumour Antigens and Subunit Vaccines. BMC Bioinform. 2007, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, I.; Bangov, I.; Flower, D.R.; Doytchinova, I. AllerTOP v.2—A Server for in Silico Prediction of Allergens. J. Mol. Model. 2014, 20, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Zaretskaya, I.; Raytselis, Y.; Merezhuk, Y.; McGinnis, S.; Madden, T.L. NCBI BLAST: A Better Web Interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W5–W9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebditch, M.; Carballo-Amador, M.A.; Charonis, S.; Curtis, R.; Warwicker, J. Protein–Sol: A Web Tool for Predicting Protein Solubility from Sequence. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.M. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Springer Protocols Handbooks Serie; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-58829-343-5. [Google Scholar]

- C-IMMSIM. Available online: https://kraken.iac.rm.cnr.it/C-IMMSIM/index.php (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Silva, A.J.D.; Jesus, A.L.S.; Leal, L.R.S.; Silva, G.A.S.; Melo, C.M.L.; Freitas, A.C. Pichia Pastoris Displaying ZIKV Protein Epitopes from the Envelope and NS1 Induce in Vitro Immune Activation. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2545–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, R.; Mahajan, S.; Overton, J.A.; Dhanda, S.K.; Martini, S.; Cantrell, J.R.; Wheeler, D.K.; Sette, A.; Peters, B. The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB): 2018 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D339–D343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynisson, B.; Alvarez, B.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: Improved Predictions of MHC Antigen Presentation by Concurrent Motif Deconvolution and Integration of MS MHC Eluted Ligand Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W449–W454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir Ul Qamar, M.; Rehman, A.; Tusleem, K.; Ashfaq, U.A.; Qasim, M.; Zhu, X.; Fatima, I.; Shahid, F.; Chen, L.-L. Designing of a next Generation Multiepitope Based Vaccine (MEV) against SARS-COV-2: Immunoinformatics and in Silico Approaches. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.J.D.; de Macêdo, L.S.; Leal, L.R.S.; de Jesus, A.L.S.; Freitas, A.C. Yeasts as a Promising Delivery Platform for DNA and RNA Vaccines. FEMS Yeast Res. 2021, 21, foab018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, P.C.; Henikoff, S. Predicting the Effects of Amino Acid Substitutions on Protein Function. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2006, 7, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaoui, M.R.; Yahyaoui, H. Unraveling the Stability Landscape of Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, A.J.; Loes, A.N.; Crawford, K.H.D.; Starr, T.N.; Malone, K.D.; Chu, H.Y.; Bloom, J.D. Comprehensive Mapping of Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor-Binding Domain That Affect Recognition by Polyclonal Human Plasma Antibodies. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 463–476.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees-Spear, C.; Muir, L.; Griffith, S.A.; Heaney, J.; Aldon, Y.; Snitselaar, J.L.; Thomas, P.; Graham, C.; Seow, J.; Lee, N.; et al. The Effect of Spike Mutations on SARS-CoV-2 Neutralization. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Verma, S.; Kamthania, M.; Saxena, A.K.; Pandey, K.C.; Pande, V.; Kolbe, M. Exploring the Structural Basis to Develop Efficient Multi-Epitope Vaccines Displaying Interaction with HLA and TAP and TLR3 Molecules to Prevent NIPAH Infection, a Global Threat to Human Health. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Ahammad, F.; Nain, Z.; Alam, R.; Imon, R.R.; Hasan, M.; Rahman, M.d.S. Designing a Multi-Epitope Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: An Immunoinformatics Approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, M.; Rashid, F.; Ali, S.; Sher, H.; Luo, S.; Xie, L.; Xie, Z. Immunoinformatic-Based Design of Immune-Boosting Multiepitope Subunit Vaccines against Monkeypox Virus and Validation through Molecular Dynamics and Immune Simulation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1042997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, A.D.; Pabo, C.O. Cellular Uptake of the Tat Protein from Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Cell 1988, 55, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Luo, Y.; Shibu, M.A.; Toth, I.; Skwarczynskia, M. Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Efficient Vectors for Vaccine Delivery. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Cui, X.; Yan, Z.; Tao, Y.; Shi, L.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Y.; Shi, L. Design and Evaluation of a Multi-Epitope DNA Vaccine against HPV16. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2352908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Den Dekker, W.K.; Cheng, C.; Pasterkamp, G.; Duckers, H.J. Toll like Receptor 4 in Atherosclerosis and Plaque Destabilization. Atherosclerosis 2010, 209, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, P.; Xue, Y.; Wang, J.; Jia, Z.; Wang, L.; Gong, W. Evaluation of the Consistence between the Results of Immunoinformatics Predictions and Real-World Animal Experiments of a New Tuberculosis Vaccine MP3RT. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1047306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, J.-L.; MacMicking, J.D.; Nathan, C.F. Interferon-γ and Infectious Diseases: Lessons and Prospects. Science 2024, 384, eadl2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Ramirez, N.; Woytschak, J.; Boyman, O. Interleukin-2: Biology, Design and Application. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyarzún, P.; Kobe, B. Recombinant and Epitope-Based Vaccines on the Road to the Market and Implications for Vaccine Design and Production. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Navid, A.; Farid, R.; Abbas, G.; Ahmad, F.; Zaman, N.; Parvaiz, N.; Azam, S.S. Design of a Novel Multi Epitope-Based Vaccine for Pandemic Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) by Vaccinomics and Probable Prevention Strategy against Avenging Zoonotics. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 151, 105387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, A.E.; Johnson, P. Modulation of Immune Cell Signalling by the Leukocyte Common Tyrosine Phosphatase, CD45. Cell. Signal. 2010, 22, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puck, A.; Künig, S.; Modak, M.; May, L.; Fritz, P.; Battin, C.; Radakovics, K.; Steinberger, P.; Reipert, B.M.; Crowe, B.A.; et al. The Soluble Cytoplasmic Tail of CD45 Regulates T-cell Activation via TLR4 Signaling. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 51, 3176–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remedios, K.A.; Meyer, L.; Zirak, B.; Pauli, M.L.; Truong, H.-A.; Boda, D.; Rosenblum, M.D. CD27 Promotes CD4+ Effector T Cell Survival in Response to Tissue Self-Antigen. J. Immunol. 2019, 203, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, J.; Xiao, Y.; Rossen, J.W.A.; Van Der Sluijs, K.F.; Sugamura, K.; Ishii, N.; Borst, J. During Viral Infection of the Respiratory Tract, CD27, 4-1BB, and OX40 Collectively Determine Formation of CD8+ Memory T Cells and Their Capacity for Secondary Expansion. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Peperzak, V.; Keller, A.M.; Borst, J. CD27 Instructs CD4+ T Cells to Provide Help for the Memory CD8+ T Cell Response after Protein Immunization. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudryavtsev, I.; Rubinstein, A.; Golovkin, A.; Kalinina, O.; Vasilyev, K.; Rudenko, L.; Isakova-Sivak, I. Dysregulated Immune Responses in SARS-CoV-2-Infected Patients: A Comprehensive Overview. Viruses 2022, 14, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ozaibi, L.S.; Alshaikh, M.O.; Makhdoom, M.; Alzoabi, O.M.; Busharar, H.A.; Keloth, T.R. Splenic Abscess: An Unusual Presentation of COVID-19? Dubai Med. J. 2020, 3, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluhaybi, K.A.; Alharbi, R.H.; Alhabbab, R.Y.; Aljehani, N.D.; Alamri, S.S.; Basabrain, M.; Alharbi, R.; Abdulaal, W.H.; Alfaleh, M.A.; Tamming, L.; et al. Cellular and Humoral Immunogenicity of a Candidate DNA Vaccine Expressing SARS-CoV-2 Spike Subunit 1. Vaccines 2021, 9, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.B.; Suh, Y.S.; Ryu, J.I.; Jang, H.; Oh, H.; Koo, B.-S.; Seo, S.-H.; Hong, J.J.; Song, M.; Kim, S.-J.; et al. Soluble Spike DNA Vaccine Provides Long-Term Protective Immunity against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice and Nonhuman Primates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, P. The T Cell Immune Response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeton, R.; Tincho, M.B.; Ngomti, A.; Baguma, R.; Benede, N.; Suzuki, A.; Khan, K.; Cele, S.; Bernstein, M.; Karim, F.; et al. T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Spike Cross-Recognize Omicron. Nature 2022, 603, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HLA | Description | PDB ID | Structures Removed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | |||

| HLA-A*02:01 | HLA-A*0201 human—ALWGPDPAAA. | 3UTQ | Chain C: insulin |

| HLA-A*03:01 | HIV RT-derived peptide in complex with HLA-A*0301. | 3RL1 | Chain C: peptide RT313 |

| HLA-B*35:01 | Insights into human allorecognition cross-reactivity: The structure of HLA-B35011 present in an epitope derived from cytochrome P450. | 2CIK | Chain C: peptide Ligand: GOL (glycerol) |

| HLA-B*51:01 | Binding of non-standard peptides from HLA-B*5101 complexed to the immunodominant epitope of HIV KM1 (LPPVVAKEI). | 1E27 | Chain C: HIV-1 peptide (LPPVVAKEI) |

| HLA-B*53:01 | Class I MHC molecule B*5301 complexed with the LS6 peptide (KPIVQYDNF) from the malaria parasite P. falciparum. | 1A1O | Chain C: LS6 peptide (KPIVQYDNF) |

| HLA-C*08:01 | Crystal structure of HLA-C*0801. | 4NT6 | Chain C: matrix protein 1 |

| Class II | |||

| HLA-DRB1*01:01 | Crystal structure of Staphylococcal Enterotoxin I (SEI) in complex with a human MHC class II molecule. | 2G9H | Chain A: HLA class II histocompatibility antigen, DR alpha chain Chain C: hemagglutinin Chain D: extracellular type 1 enterotoxin Ligands: EPE (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid), SO4 (sulfate ion), DIO (1,4-diethylene dioxide), and ZN (zinc ion) |

| Epitope * | Sequence | Receptor | HLA | Percentile Rank | Immunogenicity | Conservation (%) | Mutation (Variant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S56–64 | LPFFSNVTW | HLA-I | HLA-B*53:01 | 0.01 | 0.04613 | 100 (27/27) | |

| HLA-B*51:01 | 0.2 | ||||||

| S84–92 | LPFNDGVYF | HLA-I | HLA-B*35:01 | 0.01 | 0.11767 | 96 (26/27) | NSFTRGVYY (Omicron—B.1.1.529) |

| HLA-B*15:02 | 0.12 | ||||||

| S131–141 | FQFCNDPFL | HLA-I | HLA-A*02:06 | 0.17 | 0.05737 | 96 (26/27) | FQFCNYPFL (Brazil—P.1) |

| HLA-C*08:01 | 0.56 | ||||||

| HLA-A*02:01 | 0.41 | ||||||

| S115–129 | QSLLIVNNATNVVIK | HLA-II | HLA-DRB1*13:02 | 1.9 | - | 100 (27/27) | |

| S447–461 | GNYNYLYRLFRKSNL | HLA-II | HLA-DRB1*11:01 | 4.5 | - | 80 (22/27) | GNYNYRYRLFRKSNL (USA—B.1.427 and B.1.429 India—B.1.617.1 and B.1.617.2 Peru—C.37) |

| S512–526 | VLSFELLHAPATVCG | HLA-II | HLA-DRB1*01:01 | 0.67 | - | 100 (27/27) | |

| S72–81 | GTNGTKRFDN | B cell | - | - | 92 (25/27) | GTNGTKRFAN (South Africa—B.1.351) GTNVIKRFDN (Peru—C.37) | |

| S493-506 | QSYGFQPTNGVGYQ | B cell | - | - | 85 (23/27) | QSYGFQPTYGVGYQ (United Kingdom—B.1.1.7 South Africa—B.1.351 Brazil—P.1) YQAGNKPCNGVAGF (Omicron—B.1.1.529) | |

| N100–111 | KMKDLSPRWYFY | HLA-I | HLA-A*29:02 | 0.97 | 0.09381 | 96 (26/27) | NVSLVKPSFYVY Omicron (B.1.1.529) |

| HLA-E*01:01 | 13 | ||||||

| HLA-A*32:01 | 1.5 | ||||||

| HLA-A*01:01 | 3.1 | ||||||

| HLA-A*03:01 | 2.6 | ||||||

| HLA-A*31:01 | 3.9 | ||||||

| HLA-B*15:01 | 0.59 | ||||||

| N343–354 | DPNFKDQVILLN | HLA-I | HLA-B*35:03 | 12 | −0.03586 | 96 (26/27) | SFYVYSRVKNLN Omicron (B.1.1.529) |

| N220–234 | ALLLLDRLNQLESKM | HLA-II | HLA-DRB1*11:04 | 17 | - | 88 (24/27) | ALLLLDRLNQLESKI (Brazil—P.2 USA—B.1.526) ALRLCAYCCNIVNVS (Omicron—B.1.1.529) |

| HLA-DRB1*11:06 | 20 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:11 | 17 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:21 | 38 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:07 | 40 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*11:02 | 39 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*11:21 | 40 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:22 | 39 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:04 | 32 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*08:06 | 17 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*11:28 | 24 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:05 | 24 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*08:04 | 32 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*11:14 | 40 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:23 | 40 | ||||||

| N266–280 | KAYNVTQAFGRRGPE | HLA-II | HLA-DRB5*01:05 | 0.03 | - | 96 (26/27) | CAYCCNIVNVSLVKP (Omicron—B.1.1.529) |

| HLA-DRB5*01:01 | 0.03 | ||||||

| N316–330 | FFGMSRIGMEVTPSG | HLA-II | HLA-DRB1*11:06 | 61 | - | 96 (26/27) | FYVYSRVKNLNSSRV (Omicron—B.1.1.529) |

| HLA-DRB1*08:04 | 63 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*11:28 | 63 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:05 | 63 | ||||||

| HLA-DRB1*13:21 | 71 | ||||||

| N138–153 | EGALNTPKDHIGTRNP | B cell | - | 92 (25/27) | EGALNTPKDHIGIRNP China-Shenzhen (Omicron—B.1.1.529) | ||

| N251–266 | KSAAEASKKPRQKRTA | B cell | - | 96 (26/27) | NIVNVSLVKPSFYVYS (Omicron—B.1.1.529) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Invenção, M.d.C.V.; Macêdo, L.S.d.; Moura, I.A.d.; Santos, L.A.B.d.O.; Espinoza, B.C.F.; Pinho, S.S.d.; Leal, L.R.S.; Santos, D.L.d.; São Marcos, B.d.F.; Elsztein, C.; et al. Design and Immune Profile of Multi-Epitope Synthetic Antigen Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2: An In Silico and In Vivo Approach. Vaccines 2025, 13, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13020149

Invenção MdCV, Macêdo LSd, Moura IAd, Santos LABdO, Espinoza BCF, Pinho SSd, Leal LRS, Santos DLd, São Marcos BdF, Elsztein C, et al. Design and Immune Profile of Multi-Epitope Synthetic Antigen Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2: An In Silico and In Vivo Approach. Vaccines. 2025; 13(2):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13020149

Chicago/Turabian StyleInvenção, Maria da Conceição Viana, Larissa Silva de Macêdo, Ingrid Andrêssa de Moura, Lucas Alexandre Barbosa de Oliveira Santos, Benigno Cristofer Flores Espinoza, Samara Sousa de Pinho, Lígia Rosa Sales Leal, Daffany Luana dos Santos, Bianca de França São Marcos, Carolina Elsztein, and et al. 2025. "Design and Immune Profile of Multi-Epitope Synthetic Antigen Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2: An In Silico and In Vivo Approach" Vaccines 13, no. 2: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13020149

APA StyleInvenção, M. d. C. V., Macêdo, L. S. d., Moura, I. A. d., Santos, L. A. B. d. O., Espinoza, B. C. F., Pinho, S. S. d., Leal, L. R. S., Santos, D. L. d., São Marcos, B. d. F., Elsztein, C., Sousa, G. F. d., Souza-Silva, G. A. d., Barros, B. R. d. S., Cruz, L. C. d. O., Maux, J. M. d. L., Silva Neto, J. d. C., Melo, C. M. L. d., Silva, A. J. D., Batista, M. V. d. A., & Freitas, A. C. d. (2025). Design and Immune Profile of Multi-Epitope Synthetic Antigen Vaccine Against SARS-CoV-2: An In Silico and In Vivo Approach. Vaccines, 13(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13020149