Assessing COVID-19 Infection and Severe Disease Risk in Cancer Patients and Survivors: The Role of Vaccination Status, Circulating Variants, and Comorbidities—A Population-Based Study in Northern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Exposure Definition

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Follow-Up

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Comparison with Previous Literature

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CCI | Charlson comorbidity index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Kuderer, N.M.; Choueiri, T.K.; Shah, D.P.; Shyr, Y.; Rubinstein, S.M.; Rivera, D.R.; Shete, S.; Hsu, C.Y.; Desai, A.; de Lima Lopes, G.; et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): A cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, E.C.; Hwang, J.E.; Kim, K.; Kim, S.J.; Jung, J.H.; Lee, H.; Sun, K.H.; Han, M.A. Prognostic factors of mortality in patients with cancer infected with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis using the GRADE approach. Int. J. Cancer 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Sheng, Y.; Huang, C.; Jin, Y.; Xiong, N.; Jiang, K.; Lu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Dong, Y.; et al. Clinical characteristics, outcomes, and risk factors for mortality in patients with cancer and COVID-19 in Hubei, China: A multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangone, L.; Gioia, F.; Mancuso, P.; Bisceglia, I.; Ottone, M.; Vicentini, M.; Pinto, C.; Giorgi Rossi, P. Cumulative COVID-19 incidence, mortality and prognosis in cancer survivors: A population-based study in Reggio Emilia, Northern Italy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 660784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesen, T.B.; Smeland, S.; Aaserud, S.; Buanes, E.A.; Skog, A.; Ursin, G.; Helland, Å. COVID-19 in cancer patients, risk factors for disease and adverse outcome, a population-based study from Norway. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 652535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, R.T.; Chalasani, P.; Wei, R.; Pennington, D.; Quigley, M.M.; Zhong, H.; Gage, D.; Anderson, A.; Kelly, D.; Licitra, E.J.; et al. Immune responses to two-dose SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in patients with solid tumors on active immunosuppressive therapy. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 548–550. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Lei, X.; Zhao, H.; Scheet, P.; Giordano, S.H. Evaluation of COVID-19 mortality and adverse outcomes in US patients with or without cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicentini, M.; Venturelli, F.; Mancuso, P.; Bisaccia, E.; Zerbini, A.; Massari, M.; Cossarizza, A.; De Biasi, S.; Pezzotti, P.; Bedeschi, E.; et al. COVID-19 Working Group. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection by vaccination status, predominant variant and time from prior infection: A cohort study, Reggio Emilia province, Italy, February 2020 to February 2022. Eurosurveillance 2023, 28, 2200494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, W.; Pan, C.; Cai, X.; Xu, J.; Qiu, X.; Yan, Y.; Tan, C. The N501Y spike substitution enhances SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Nature 2021, 593, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.; Stowe, J.; Kirsebom, F.; Toffa, S.; Rickeard, T.; Gallagher, E.; Gower, C.; Kall, M.; Champion, J.; Chand, M.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1532–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, M.; Puopolo, M.; Morciano, C.; Spuri, M.; Alegiani, S.S.; Filia, A.; D’Ancona, F.; Del Manso, M.; Riccardo, F.; Tallon, M.; et al. Effectiveness of mRNA vaccines and waning of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 during predominant circulation of the delta variant in Italy: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2022, 376, e069052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, P.; Trentini, F.; Guzzetta, G.; Marziano, V.; Mammone, A.; Schepisi, M.S.; Poletti, P.; Grané, C.M.; Manica, M.; Del Manso, M.; et al. COVID-19 National Microbiology Surveillance Study Group. Co-circulation of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha and Gamma variants in Italy, February and March 2021. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, E.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Spila Alegiani, S.; Trifirò, G.; Pitter, G.; Leoni, O.; Cereda, D.; Marino, M.; Pellizzari, M.; Fabiani, M.; et al. Survival of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Northern Italy: A Population-Based Cohort Study by the ITA-COVID-19 Network. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 12, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangone, L.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Taborelli, M.; Toffolutti, F.; Mancuso, P.; Dal Maso, L.; Gobbato, M.; Clagnan, E.; Del Zotto, S.; Ottone, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccination and risk of death in people with an oncological disease in northeast Italy. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamboj, M.; Bohlke, K.; Baptiste, D.M.; Dunleavy, K.; Fueger, A.; Jones, L.; Kelkar, A.H.; Law, L.Y.; Lefebvre, K.B.; Ljungman, P.; et al. Vaccination of adults with cancer: ASCO guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1699–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Wei, Z.; Wu, X. Impaired serological response to COVID-19 vaccination following anticancer therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 4860–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Zhang, K. Predictors of poor serologic response to COVID-19 vaccine in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 172, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, V.G.; Teh, B.W. COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer and patients receiving HSCT or CAR-T therapy: Immune response, real-world effectiveness, and implications for the future. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 228 (Suppl. S1), S55–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, L.; Laing, A.G.; Muñoz-Ruiz, M.; McKenzie, D.R.; Del Barrio, I.D.M.; Alaguthurai, T.; Domingo-Vila, C.; Hayday, T.S.; Graham, C.; Seow, J.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: Interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, A.; Casado, J.L.; Longo, F.; Serrano, J.J.; Saavedra, C.; Velasco, H.; Martin, A.; Chamorro, J.; Rosero, D.; Fernández, M.; et al. Limited T cell response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine among patients with cancer receiving different cancer treatments. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 166, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasri, M.; Bshesh, K.; Khan, W.; Mushannen, M.; Salameh, M.A.; Shafiq, A.; Vattoth, A.L.; Elkassas, N.; Zakaria, D. Cancer patients and the COVID-19 vaccines: Considerations and challenges. Cancers 2022, 14, 5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosting, S.F.; van der Veldt, A.A.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H.; Fehrmann, R.S.; van Binnendijk, R.S.; Dingemans, A.M.C.; Smit, E.F.; Hiltermann, T.J.N.; den Hartog, G.; Jalving, M.; et al. mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccination in patients receiving chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or chemoimmunotherapy for solid tumours: A prospective, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population With Cancer | Population Without Cancer | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period of Infection | Period of Infection | Period of Infection | Period of Infection | |||||||

| From 20 February 2020 to 20 December 2021 | From 1 January 2022 to 30 September 2022 | From 20 February 2020 to 20 December 2021 | From 1 January 2022 to 30 September 2022 | |||||||

| n * | Person-Days | Infections | Person-Days | Infections | n * | Person-Days | Infections | Person-Days | Infections | |

| Overall | 26,928 | 18,665,758 | 2591 | 7,287,029 | 6544 | 511,588 | 333,498,175 | 52,315 | 123,371,182 | 129,398 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 12,067 | 8,326,317 | 1190 | 3,233,336 | 2812 | 253,329 | 165,256,721 | 25,865 | 61,568,939 | 60,125 |

| Female | 14,861 | 10,339,441 | 1401 | 4,053,693 | 3732 | 258,259 | 168,241,454 | 26,450 | 61,802,243 | 69,273 |

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 0–4 | 10 | 3540 | 2 | 1100 | 0 | 21,241 | 5,323,859 | 1041 | 1,790,411 | 2447 |

| 5–17 | 113 | 73,584 | 14 | 27,223 | 41 | 70,367 | 47,820,086 | 8498 | 16,395,107 | 22,347 |

| 18–34 | 536 | 324,985 | 68 | 116,849 | 166 | 93,184 | 60,169,850 | 10,746 | 22,302,927 | 25,678 |

| 35–64 | 8958 | 5,855,449 | 956 | 2,234,436 | 2917 | 227,348 | 150,093,621 | 23,727 | 55,714,636 | 58,576 |

| 65–79 | 10,657 | 7,300,650 | 849 | 2,883,145 | 2289 | 67,820 | 46,891,575 | 5071 | 18,349,242 | 11,451 |

| 80+ | 6654 | 5,107,550 | 702 | 2,024,276 | 1083 | 31,628 | 23,199,184 | 3232 | 8,818,859 | 4229 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||||||||

| 0 | 21,777 | 15,539,301 | 2043 | 6,224,630 | 5609 | 491,821 | 321,732,201 | 50,165 | 119,394,475 | 125,929 |

| 1 | 2443 | 1,556,706 | 239 | 550,944 | 460 | 13,471 | 8,238,709 | 1382 | 2,873,016 | 2510 |

| 2 | 820 | 486,989 | 114 | 156,583 | 155 | 4151 | 2,383,848 | 486 | 767,292 | 682 |

| 3 | 1888 | 1,082,762 | 195 | 354,872 | 320 | 2145 | 1,143,417 | 282 | 336,399 | 277 |

| Years from diagnosis | ||||||||||

| <2 | 2,508,596 | 500 | 880,032 | 1053 | ||||||

| 2–5 | 3,941,658 | 553 | 1,497,950 | 1394 | ||||||

| >5 | 12,215,504 | 1538 | 4,909,047 | 4097 | ||||||

| Immunization status | ||||||||||

| No infection, no vaccine | 11,841,178 | 2210 | 321,217 | 435 | 251,912,448 | 46,243 | 17,809,840 | 22,462 | ||

| No infection, 1 dose | 918,722 | 80 | 23,883 | 36 | 14,630,632 | 1488 | 1,094,708 | 2753 | ||

| No infection, 2 doses | 4,736,273 | 257 | 331,742 | 588 | 53,025,309 | 4192 | 14,500,761 | 31,051 | ||

| No infection, 3 or more doses | 567,032 | 34 | 5,571,101 | 5059 | 2,708,425 | 228 | 65,025,072 | 61,709 | ||

| Infection, no vaccine | 222,370 | 8 | 88,452 | 73 | 5,521,098 | 127 | 4,970,897 | 3902 | ||

| Infection, 1 dose | 228,024 | 1 | 32,247 | 34 | 3,739,067 | 22 | 1,765,645 | 1477 | ||

| Infection, 2 doses | 141,443 | 1 | 352,240 | 159 | 1,898,408 | 14 | 10,531,276 | 3691 | ||

| Infection, 3 or more doses | 10,716 | 0 | 566,147 | 160 | 62,788 | 1 | 7,672,983 | 2353 | ||

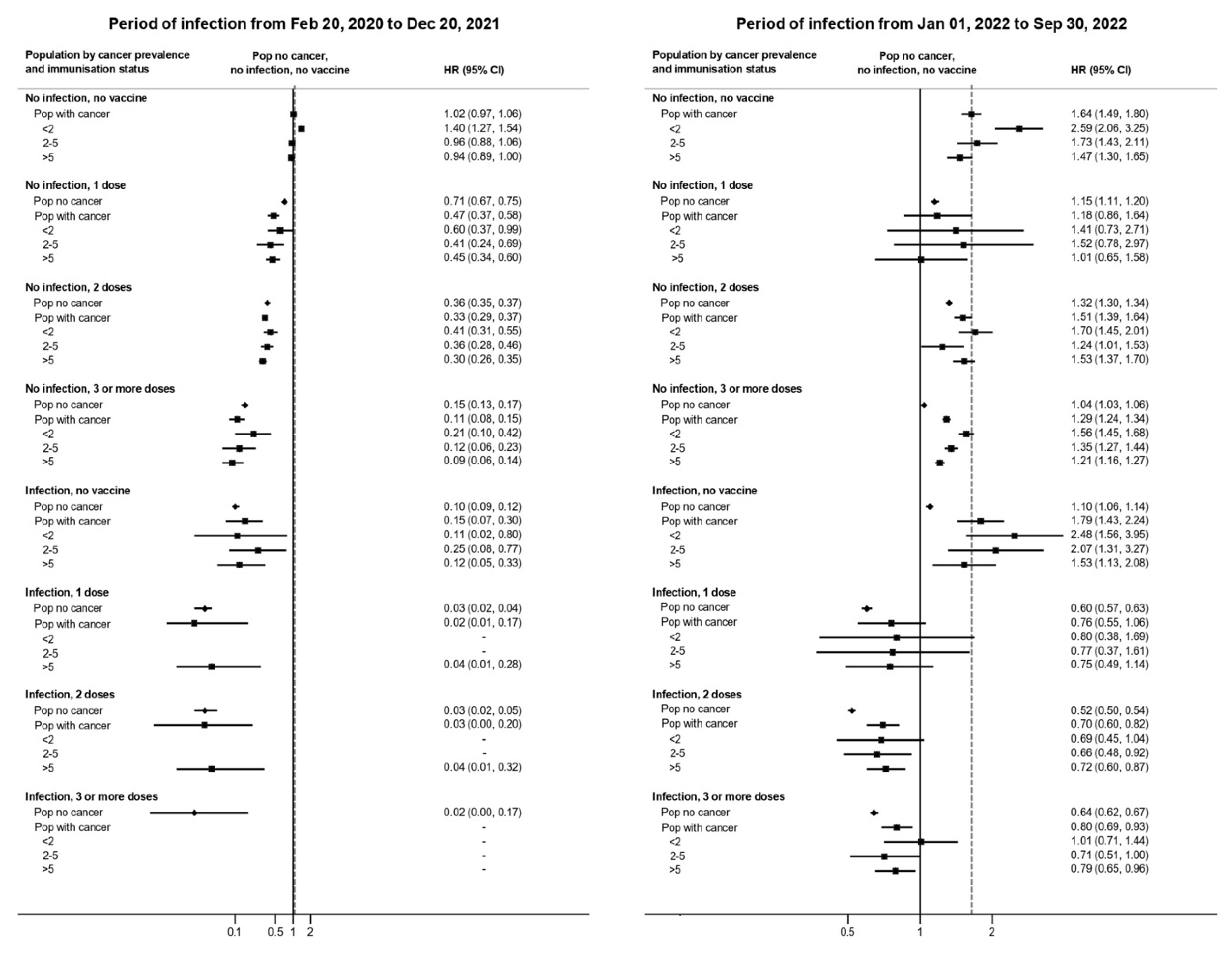

| Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period of Infection | Period of Infection | |||||

| From 20 February 2020 to 20 December 2021 | From 1 January 2022 to 30 September 2022 | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.11 |

| Years from diagnosis | - | - | ||||

| <2 | 1.37 | 1.25 | 1.50 | 1.35 | 1.28 | 1.44 |

| 2–5 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 1.07 | 1.12 | 1.06 | 1.18 |

| >5 | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.05 |

| 0–4 | ||||||

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 2.88 | 0.61 | 13.55 | - | - | - |

| 5–17 | ||||||

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.10 | 0.66 | 1.84 | 1.16 | 0.86 | 1.55 |

| 18–34 | ||||||

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.25 | 0.99 | 1.59 | 1.24 | 1.06 | 1.44 |

| 35–64 | ||||||

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.04 | 0.97 | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.03 | 1.11 |

| 65–79 | ||||||

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.98 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1.19 |

| 80+ | ||||||

| Cancer | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 1.07 | 1.01 | 1.13 |

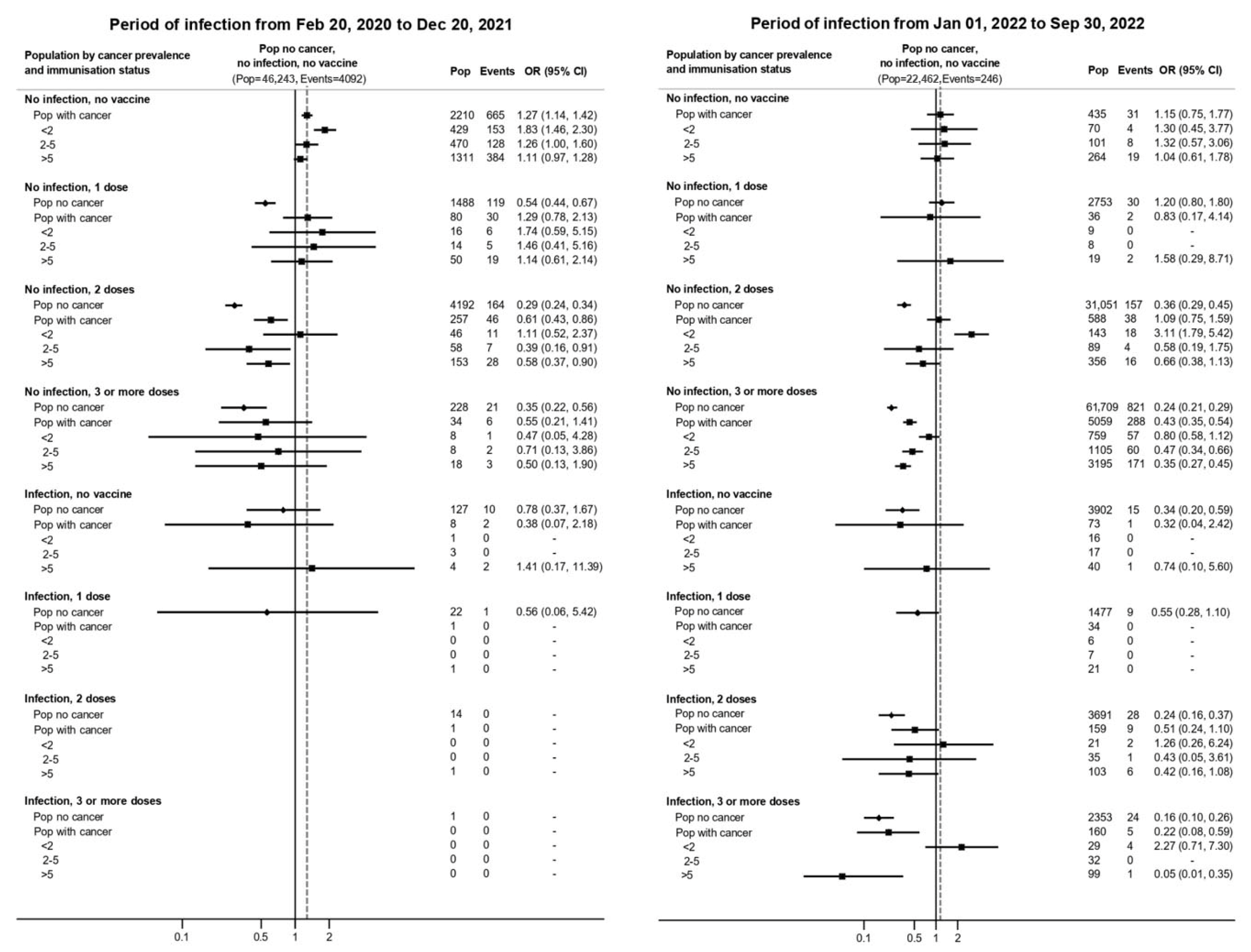

| Risk of Severe Disease and Death from COVID-19 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period of Infection | Period of Infection | |||||||||

| From 20 February 2020 to 20 December 2021 | From 1 January 2022 to 30 September 2022 | |||||||||

| n | Events | OR | 95% CI | n | Events | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Cancer | ||||||||||

| No | 52,315 | 4407 | 1 | 129,398 | 1330 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 2591 | 749 | 1.33 | 1.20 | 1.48 | 6544 | 374 | 1.67 | 1.48 | 1.90 |

| Years from diagnosis | - | - | ||||||||

| <2 | 500 | 171 | 1.94 | 1.57 | 2.41 | 1053 | 85 | 3.38 | 2.66 | 4.31 |

| 2–5 | 553 | 142 | 1.28 | 1.02 | 1.59 | 1394 | 73 | 1.68 | 1.30 | 2.17 |

| >5 | 1538 | 436 | 1.19 | 1.05 | 1.36 | 4097 | 216 | 1.37 | 1.17 | 1.60 |

| 0–64 # | ||||||||||

| Cancer | ||||||||||

| No | 44,012 | 1711 | 1 | 110,855 | 330 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 1040 | 107 | 1.42 | 1.14 | 1.77 | 2812 | 44 | 3.16 | 2.22 | 4.50 |

| 65–79 | ||||||||||

| Cancer | ||||||||||

| No | 5071 | 1228 | 1 | 12,827 | 327 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 849 | 284 | 1.36 | 1.16 | 1.61 | 2279 | 108 | 1.55 | 1.23 | 1.96 |

| 80+ | ||||||||||

| Cancer | ||||||||||

| No | 3232 | 1468 | 1 | 5716 | 673 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 702 | 358 | 1.13 | 0.95 | 1.33 | 1453 | 222 | 1.48 | 1.24 | 1.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vicentini, M.; Mancuso, P.; Venturelli, F.; Mezzadri, S.; Bisaccia, E.; Zerbini, A.; Mangone, L.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; on behalf of the Reggio Emilia COVID-19 Working Group. Assessing COVID-19 Infection and Severe Disease Risk in Cancer Patients and Survivors: The Role of Vaccination Status, Circulating Variants, and Comorbidities—A Population-Based Study in Northern Italy. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121223

Vicentini M, Mancuso P, Venturelli F, Mezzadri S, Bisaccia E, Zerbini A, Mangone L, Giorgi Rossi P, on behalf of the Reggio Emilia COVID-19 Working Group. Assessing COVID-19 Infection and Severe Disease Risk in Cancer Patients and Survivors: The Role of Vaccination Status, Circulating Variants, and Comorbidities—A Population-Based Study in Northern Italy. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121223

Chicago/Turabian StyleVicentini, Massimo, Pamela Mancuso, Francesco Venturelli, Sergio Mezzadri, Eufemia Bisaccia, Alessandro Zerbini, Lucia Mangone, Paolo Giorgi Rossi, and on behalf of the Reggio Emilia COVID-19 Working Group. 2025. "Assessing COVID-19 Infection and Severe Disease Risk in Cancer Patients and Survivors: The Role of Vaccination Status, Circulating Variants, and Comorbidities—A Population-Based Study in Northern Italy" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121223

APA StyleVicentini, M., Mancuso, P., Venturelli, F., Mezzadri, S., Bisaccia, E., Zerbini, A., Mangone, L., Giorgi Rossi, P., & on behalf of the Reggio Emilia COVID-19 Working Group. (2025). Assessing COVID-19 Infection and Severe Disease Risk in Cancer Patients and Survivors: The Role of Vaccination Status, Circulating Variants, and Comorbidities—A Population-Based Study in Northern Italy. Vaccines, 13(12), 1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121223