Engineering Anti-Tumor Immunity: An Immunological Framework for mRNA Cancer Vaccines

Abstract

1. Introduction

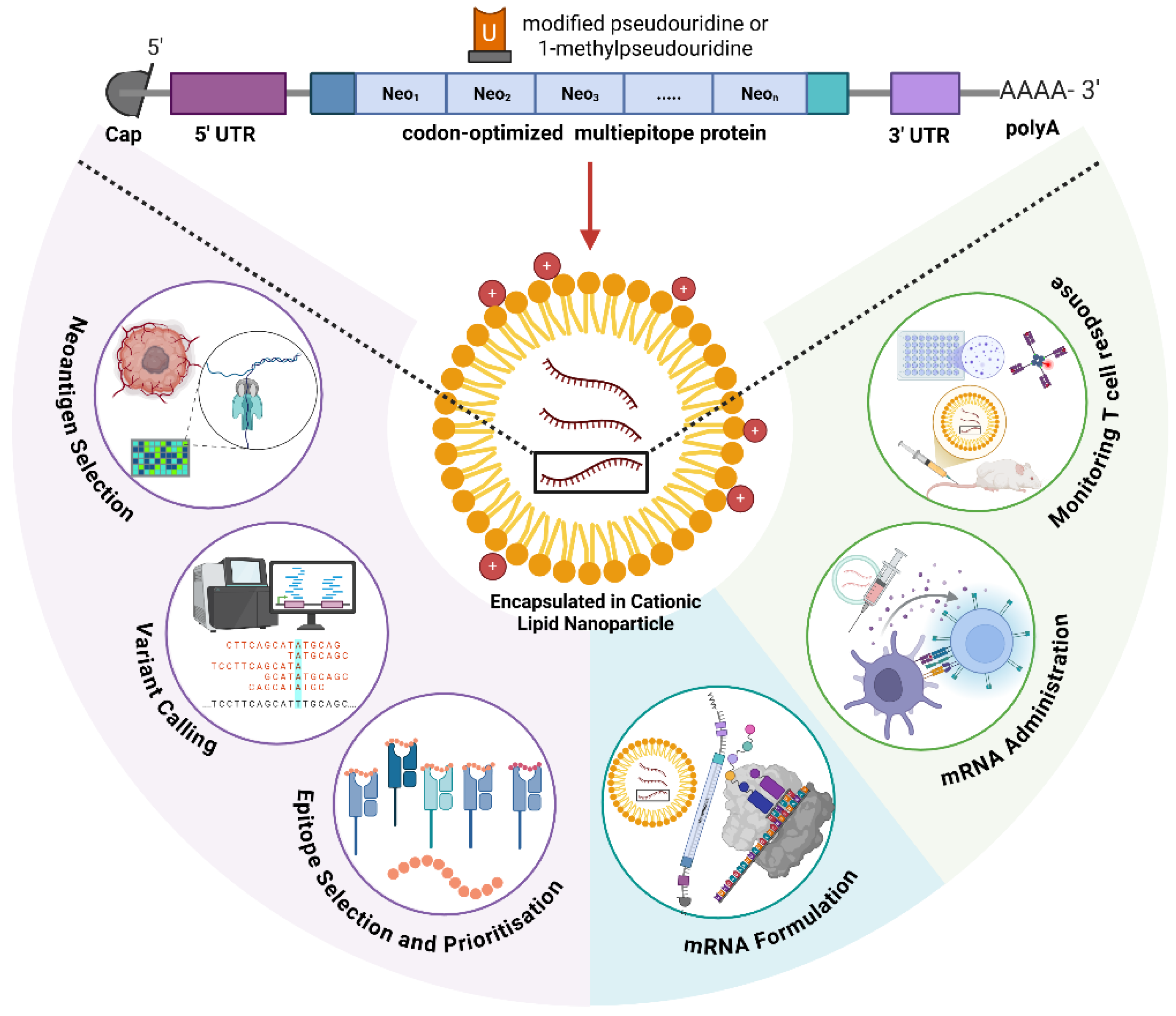

2. Molecular Engineering of mRNA Vaccines

2.1. Nucleoside Modifications: Balancing Expression and Immunogenicity

2.2. Untranslated Region Engineering: Precision Control of mRNA Function

2.2.1. 5′ UTR Design and Optimization

2.2.2. 3′ UTR Engineering

2.3. Poly(A) Tail Length and Tissue-Specific Control

2.4. Codon Optimization: Multi-Parameter Molecular Engineering

2.5. RNA Secondary Structure and GC Content Management

2.6. Innate Immune Recognition Motifs

3. Antigen Selection and Epitope Engineering

3.1. Neoantigen Discovery: Computational Pipelines and Predictive Algorithms

3.1.1. Pipeline Overview and Candidate Generation

3.1.2. Comparative Benchmarking of Prediction Algorithms

- Binding accuracy: sensitivity/specificity of peptide–HLA binding prediction (often compared to MS–ligand or binding assay data).

- Presentation accuracy: ability to predict that a peptide will be processed and presented (proteasome/TAP/HLA loading).

- Immunogenicity recall/precision: fraction of predicted peptides that elicit T cell responses (tetramer/ELISPOT) in validation cohorts.

- Ranking power: ability to place true immunogenic peptides high in the prioritized list (e.g., top 10 % or top 20). For example, Schäfer et al. (2023) in Bioinformatics described ScanNeo2, a workflow integrating fusion, splicing, and SNV/indel events, and showed improved ranking performance [56].

- Allele coverage and population performance: performance across rare HLA alleles and diverse ethnicities.

- Source diversity: capacity to detect neoantigens from SNVs, indels, fusions, structural variants (SVs), and viral epitopes, e.g., Shi et al. (2023) developed NeoSV to incorporate structural variation-derived neoantigens from >2500 whole genomes [57].

3.1.3. Long-Read Sequencing vs. Short-Read in Neoantigen Discovery

3.2. Addressing Epitope Immunogenicity, Immunodominance, and Intra-Allelic Competition

3.2.1. Predicting and Enhancing Epitope Immunogenicity

3.2.2. Immunodominance and Intra-Allelic Competition

3.2.3. Epitope Number Optimization and Immunodominance Management

3.2.4. Epitope Order Effects and Processing Optimization in mRNA Constructs

3.3. Critical Design Gaps and the Road to Optimized Neoantigen Vaccines

4. Delivery Platform Engineering and Targeting Strategies

4.1. Lipid Nanoparticle Technology: Compositional Precision and Structure–Function Relationships

4.2. Ionizable Lipid Chemistry: Beyond First-Generation Designs

4.3. Overcoming Hepatotropism: Tissue-Specific Targeting Innovations

4.4. PEGylation Dilemma: Anti-PEG Immunity and Alternative Stealth Strategies

4.5. Beyond Lipids: Emerging Delivery Platforms and Critical Limitations

5. Future Perspectives and Conclusion

5.1. Strategies That Work: Validated Combination Approaches

5.2. Next Step in mRNA Vaccine Platforms

5.2.1. Circular and Self-Amplifying RNA

5.2.2. Toward Integrated Precision Immunotherapy

5.3. Concluding Remarks: From Rational Design to Therapeutic Reality

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LNP | lipid nanoparticle |

| HLA | human leukocyte antigen |

| m1Ψ | N1-methylpseudouridine |

| DC | dendritic cell |

| PLGA | poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| APC | antigen-presenting cell |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex |

References

- Sahin, U.; Türeci, Ö. Personalized vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Science 2018, 359, 1355–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, L.A.; Sethna, Z.; Soares, K.C.; Olcese, C.; Pang, N.; Patterson, E.; Lihm, J.; Ceglia, N.; Guasp, P.; Chu, A.; et al. Personalized RNA neoantigen vaccines stimulate T cells in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2023, 618, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T. Personalized anti-cancer vaccine combining mRNA and immunotherapy tested in melanoma trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2379–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.A.; Fearon, D.T. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science 2015, 348, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; Chan, V.; Fearon, D.F.; Merad, M.; Coussens, L.M.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Hedrick, C.C.; et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, N.; Swanton, C. Clonal Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution: Past, Present, and the Future. Cell 2017, 168, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, P.; Adachi, H.; Yu, Y.-T. The Critical Contribution of Pseudouridine to mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 789427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, K.J.; Mir, F.F.; Jhunjhunwala, S.; Kaczmarek, J.C.; Hurtado, J.E.; Yang, J.H.; Webber, M.J.; Kowalski, P.S.; Heartlein, M.W.; DeRosa, F.; et al. Efficacy and immunogenicity of unmodified and pseudouridine-modified mRNA delivered systemically with lipid nanoparticles in vivo. Biomaterials 2016, 109, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, K.D.; Meier, J.L. Modifications in an Emergency: The Role of N1-Methylpseudouridine in COVID-19 Vaccines. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, X. Detailed Dissection and Critical Evaluation of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA Vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.R.; Muramatsu, H.; Nallagatla, S.R.; Bevilacqua, P.C.; Sansing, L.H.; Weissman, D.; Karikó, K. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA enhances translation by diminishing PKR activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 5884–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borchardt, E.K.; Martinez, N.M.; Gilbert, W.V. Regulation and Function of RNA Pseudouridylation in Human Cells. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2020, 54, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulroney, T.E.; Pöyry, T.; Yam-Puc, J.C.; Rust, M.; Harvey, R.F.; Kalmar, L.; Horner, E.; Booth, L.; Ferreira, A.P.; Stoneley, M.; et al. N1-methylpseudouridylation of mRNA causes +1 ribosomal frameshifting. Nature 2024, 625, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyler, D.E.; Franco, M.K.; Batool, Z.; Wu, M.Z.; Dubuke, M.L.; Dobosz-Bartoszek, M.; Jones, J.D.; Polikanov, Y.S.; Roy, B.; Koutmou, K.S. Pseudouridinylation of mRNA coding sequences alters translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23068–23074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerneckis, J.; Cui, Q.; He, C.; Yi, C.; Shi, Y. Decoding pseudouridine: An emerging target for therapeutic development. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 43, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, S.; Maser, K.; Zillinger, T.; Bartok, E. To modify or not to modify—That is still the question for some mRNA applications. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre, M.S.; Rauch, S.; Roth, N.; Yu, J.; Chandrashekar, A.; Mercado, N.B.; He, X.; Liu, J.; McMahan, K.; Martinot, A.; et al. Optimization of non-coding regions for a non-modified mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Nature 2022, 601, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thess, A.; Grund, S.; Mui, B.L.; Hope, M.J.; Baumhof, P.; Fotin-Mleczek, M.; Schlake, T. Sequence-engineered mRNA Without Chemical Nucleoside Modifications Enables an Effective Protein Therapy in Large Animals. Mol. Ther. 2015, 23, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Cai, J.; Li, H.; Qiu, M. N1-methylpseudouridine modification level correlates with protein expression, immunogenicity, and stability of mRNA. MedComm 2024, 5, e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, C.J.C.; Wada, S.; Kotake, K.; Kameda, S.; Matsuura, S.; Sakashita, S.; Park, S.; Sugiyama, H.; Kuang, Y.; Saito, H. N 1-Methylpseudouridine substitution enhances the performance of synthetic mRNA switches in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.C.; Sekhon, S.S.; Shin, W.-R.; Ahn, G.; Cho, B.-K.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Kim, Y.-H. Modifications of mRNA vaccine structural elements for improving mRNA stability and translation efficiency. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2022, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Hair, S.; Fedak, S.; Wang, B.; Linder, J.; Havens, K.; Certo, M.; Seelig, G. Optimizing 5′UTRs for mRNA-delivered gene editing using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepotec, Z.; Aneja, M.K.; Geiger, J.; Hasenpusch, G.; Plank, C.; Rudolph, C. Maximizing the Translational Yield of mRNA Therapeutics by Minimizing 5′-UTRs. Tissue Eng. Part A 2019, 25, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. Features in the 5′ non-coding sequences of rabbit alpha and beta-globin mRNAs that affect translational efficiency. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 235, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.M.; Ujita, A.; Hill, E.; Yousif-Rosales, S.; Smith, C.; Ko, N.; McReynolds, T.; Cabral, C.R.; Escamilla-Powers, J.R.; Houston, M.E. Cap 1 Messenger RNA Synthesis with Co-transcriptional CleanCap® Analog by In Vitro Transcription. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Xue, Y.; Dang, S.; Zhai, J. Technological breakthroughs and advancements in the application of mRNA vaccines: A comprehensive exploration and future prospects. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1524317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y.; Yu, D.; Li, Y.; Huang, K.; Shen, Y.; Cong, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M. A 5′ UTR language model for decoding untranslated regions of mRNA and function predictions. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2024, 6, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazandeh, S.; Ozden, F.; Hincer, A.; Seker, U.O.S.; Cicek, A.E. UTRGAN: Learning to generate 5′ UTR sequences for optimized translation efficiency and gene expression. Bioinform. Adv. 2025, 5, vbaf134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Xu, L.; Yan, Z.; Hu, Y. UTR-Insight: Integrating deep learning for efficient 5′ UTR discovery and design. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Huo, M.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Qin, S.; Luo, J.; Qin, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Duan, X.; et al. A novel deep generative model for mRNA vaccine development: Designing 5′ UTRs with N1-methyl-pseudouridine modification. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 1814–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froechlich, G.; Sasso, E. We ARE boosting translation: AU-rich elements for enhanced therapeutic mRNA translation. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandini von Niessen, A.G.; Poleganov, M.A.; Rechner, C.; Plaschke, A.; Kranz, L.M.; Fesser, S.; Diken, M.; Löwer, M.; Vallazza, B.; Beissert, T.; et al. Improving mRNA-Based Therapeutic Gene Delivery by Expression-Augmenting 3′ UTRs Identified by Cellular Library Screening. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2019, 27, 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biziaev, N.; Shuvalov, A.; Salman, A.; Egorova, T.; Shuvalova, E.; Alkalaeva, E. The impact of mRNA poly(A) tail length on eukaryotic translation stages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 7792–7808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preiss, T. The End in Sight: Poly(A), Translation and mRNA Stability in Eukaryotes. In Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet]; Landes Bioscience: Austin, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, K.; Bartel, D.P. The molecular basis of coupling between poly(A)-tail length and translational efficiency. eLife 2021, 10, e66493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrett, B.J.; Yamaoka, S.; Barry, M.A. Reducing off-target expression of mRNA therapeutics and vaccines in the liver with microRNA binding sites. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2024, 33, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlake, T.; Thess, A.; Fotin-Mleczek, M.; Kallen, K.-J. Developing mRNA-vaccine technologies. RNA Biol. 2012, 9, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikov, V.; Terenin, I.; Shepelkova, G.; Yeremeev, V.; Kolmykov, S.; Nagornykh, M.; Kolosova, E.; Sokolova, T.; Zaborova, O.; Kukushkin, I.; et al. Untranslated Region Sequences and the Efficacy of mRNA Vaccines against Tuberculosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Richardson, M.; Metkar, M. mRNA folding algorithms for structure and codon optimization. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, F. Synonymous but not Silent: The Codon Usage Code for Gene Expression and Protein Folding. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021, 90, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hia, F.; Takeuchi, O. The effects of codon bias and optimality on mRNA and protein regulation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2020, 78, 1909–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, G.; Coller, J. Codon optimality, bias and usage in translation and mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Pham, N.T.; Li, Z.; Baik, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Zhai, T.; Yu, W.; Hou, B.; Shang, T.; He, W.; et al. Advances in RNA secondary structure prediction and RNA modifications: Methods, data, and applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.04056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, I.; Eigenbrod, T.; Helm, M.; Dalpke, A.H. RNA Modifications Modulate Activation of Innate Toll-Like Receptors. Genes 2019, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, D.; Kirchhoff, F. Less is more: Biased loss of CpG dinucleotides strengthens antiviral immunity. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K.; Buckstein, M.; Ni, H.; Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA Recognition by Toll-like Receptors: The Impact of Nucleoside Modification and the Evolutionary Origin of RNA. Immunity 2005, 23, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippin, A.J.; Marconi, C.; Copling, S.; Li, N.; Braun, C.; Woody, C.; Young, E.; Gupta, P.; Wang, M.; Wu, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines sensitize tumours to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature 2025, 647, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enya, T.; Ross, S.R. Innate Sensing of Viral Nucleic Acids and Their Use in Antiviral Vaccine Development. Vaccines 2025, 13, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malathi, K.; Dong, B.; Gale, M.; Silverman, R.H. Small self-RNA generated by RNase L amplifies antiviral innate immunity. Nature 2007, 448, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasik, A.; Guydosh, N.R. The Unusual Role of Ribonuclease L in Innate Immunity. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2024, 15, e1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Cava, J.K.; Chowell, D.; Raja, R.; Mangalaparthi, K.K.; Pandey, A.; Curtis, M.; Anderson, K.S.; Singharoy, A. The electrostatic landscape of MHC-peptide binding revealed using inception networks. Cell Syst. 2024, 15, 362–373.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, W.; Su, Z.; Gu, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, S. DeepHLApan: A Deep Learning Approach for Neoantigen Prediction Considering Both HLA-Peptide Binding and Immunogenicity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaap-Johansen, A.-L.; Vujović, M.; Borch, A.; Hadrup, S.R.; Marcatili, P. T Cell Epitope Prediction and Its Application to Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 712488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibeyro, G.; Baronetto, V.; Folco, J.I.; Pastore, P.; Girotti, M.R.; Prato, L.; Morón, G.; Luján, H.D.; Fernández, E.A. Unraveling tumor specific neoantigen immunogenicity prediction: A comprehensive analysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1094236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, H.; Salm, M.; Morton, L.T.; Szukszto, M.; O’Farrell, F.; Boulton, C.; Becker, P.D.; Samuels, Y.; Swanton, C.; Mansour, M.R.; et al. Breaking the performance ceiling for neoantigen immunogenicity prediction. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 1618–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, R.A.; Guo, Q.; Yang, R. ScanNeo2: A comprehensive workflow for neoantigen detection and immunogenicity prediction from diverse genomic and transcriptomic alterations. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btad659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Jing, B.; Xi, R. Comprehensive analysis of neoantigens derived from structural variation across whole genomes from 2528 tumors. Genome Biol. 2023, 24, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, N.; Greenbaum, B.D. Trade-offs inside the black box of neoantigen prediction. Immunity 2023, 56, 2466–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurpalsdottir, B.D.; Stefansson, O.A.; Holley, G.; Beyter, D.; Zink, F.; Hardarson, M.Þ.; Sverrisson, S.Þ.; Kristinsdottir, N.; Magnusdottir, D.N.; Magnusson, O.Þ.; et al. A comparison of methods for detecting DNA methylation from long-read sequencing of human genomes. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Taha, H.B.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, Z.; Chatzipantsiou, C.; Wade, E.; Slocum, T.; Karuturi, L.; Zhao, Y.; Karmakar, S.; et al. NANOME: A Nextflow pipeline for haplotype-aware allele-specific consensus DNA methylation detection by nanopore long-read sequencing. bioRxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoLab. CLAE: A High-Fidelity Nanopore Sequencing Strategy for Read-Level Viral Variant Detection and Environmental RNA Virus Discovery. Available online: https://colab.ws/articles/10.1002%2Fadvs.202505978 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Bulik-Sullivan, B.; Busby, J.; Palmer, C.D.; Davis, M.J.; Murphy, T.; Clark, A.; Busby, M.; Duke, F.; Yang, A.; Young, L.; et al. Deep learning using tumor HLA peptide mass spectrometry datasets improves neoantigen identification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Su, H.; Guo, P.; Hong, L.; Hao, X.; Li, X. Unveiling the immunological landscape: Comprehensive characterization of neoantigen-reactive immune cells in neoantigen cancer vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1537947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, N.P.; Smith, S.A.; Wong, Y.C.; Tan, C.T.; Dudek, N.L.; Flesch, I.E.A.; Lin, L.C.W.; Tscharke, D.C.; Purcell, A.W. Kinetics of Antigen Expression and Epitope Presentation during Virus Infection. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; You, J.; Hong, L.; Liu, W.; Guo, P.; Hao, X. Neoantigen cancer vaccines: A new star on the horizon. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 274–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, T.M.; Schmidt, A.G. Protein engineering strategies for rational immunogen design. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Tian, X.; Wei, X. Cancer vaccines: Current status and future directions. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, P.S.; Lee, P.P.; Levy, D. A Theory of Immunodominance and Adaptive Regulation. Bull. Math. Biol. 2011, 73, 1645–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeletti, D.; Kosik, I.; Santos, J.J.S.; Yewdell, W.T.; Boudreau, C.M.; Mallajosyula, V.V.A.; Mankowski, M.C.; Chambers, M.; Prabhakaran, M.; Hickman, H.D.; et al. Outflanking immunodominance to target subdominant broadly neutralizing epitopes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 13474–13479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neller, M.A.; López, J.A.; Schmidt, C.W. Antigens for cancer immunotherapy. Semin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, F. Universal characterization of epitope immunodominance from a multiscale model of clonal competition in germinal centers. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 109, 064409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.; Rafiq, S.; Woo, H.G. Challenges and considerations in multi-epitope vaccine design surrounding toll-like receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 45, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalchik, K.A.; Hamelin, D.J.; Kubiniok, P.; Bourdin, B.; Mostefai, F.; Poujol, R.; Paré, B.; Simpson, S.M.; Sidney, J.; Bonneil, É.; et al. Machine learning-enhanced immunopeptidomics applied to T-cell epitope discovery for COVID-19 vaccines. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Cao, M.; Rosell, R. Neoantigen personalized vaccine plus anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer patients. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genentech, Inc. A Phase II, Open-Label, Multicenter, Randomized Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Adjuvant Autogene Cevumeran Plus Atezolizumab and mFOLFIRINOX Versus mFOLFIRINOX Alone in Patients with Resected Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. 2025. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05968326 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Shi, Y.; Shi, M.; Wang, Y.; You, J. Progress and prospects of mRNA-based drugs in pre-clinical and clinical applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merck.com. Moderna and Merck Announce mRNA-4157/V940, an Investigational Personalized mRNA Cancer Vaccine, in Combination with KEYTRUDA® (pembrolizumab), Met Primary Efficacy Endpoint in Phase 2b KEYNOTE-942 Trial. Available online: https://www.merck.com/news/moderna-and-merck-announce-mrna-4157-v940-an-investigational-personalized-mrna-cancer-vaccine-in-combination-with-keytruda-pembrolizumab-met-primary-efficacy-endpoint-in-phase-2b-keynote-94/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Barbier, A.J.; Jiang, A.Y.; Zhang, P.; Wooster, R.; Anderson, D.G. The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Z. Design and immunogenic evaluation of multi-epitope vaccines for colorectal cancer: Insights from molecular dynamics and In-Vitro studies. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1592072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepthi, V.; Sasikumar, A.; Mohanakumar, K.P.; Rajamma, U. Computationally designed multi-epitope vaccine construct targeting the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein elicits robust immune responses in silico. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhang, S.; Bi, R.; Liu, X.; Han, Z.; Li, M.; Liao, X.; Xie, T.; Bai, S.; Xie, Q.; et al. A broad-spectrum multiepitope vaccine against seasonal influenza A and B viruses in mice. eBioMedicine 2024, 106, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvmeili, J.; Baghban Kohnehrouz, B.; Gholizadeh, A.; Shanehbandi, D.; Ofoghi, H. Immunoinformatics design of a structural proteins driven multi-epitope candidate vaccine against different SARS-CoV-2 variants based on fynomer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrahimofrad, H.; Rahimnahal, S.; Zamani, J.; Jahangirian, E.; Aminzadeh, S. Designing a multi-epitope vaccine to provoke the robust immune response against influenza A H7N9. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seretis, A.; Amon, L.; Tripp, C.H.; Cappellano, G.; Hornsteiner, F.; Dieckmann, S.; Vierthaler, J.; Ortner-Tobider, D.; Kanduth, M.; Steindl, R.; et al. Multi-Epitope DC Vaccines with Melanoma Antigens for Immunotherapy of Melanoma. Vaccines 2025, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, A.S.; Moise, L.; Terry, F.; Gutierrez, A.H.; Hindocha, P.; Richard, G.; Hoft, D.F.; Ross, T.M.; Noe, A.R.; Takahashi, Y.; et al. Better Epitope Discovery, Precision Immune Engineering, and Accelerated Vaccine Design Using Immunoinformatics Tools. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Ataee, M.H.; Farzanehpour, M.; Esmaeili Guvarchin Ghaleh, H. A Comparative Analysis of Computational Strategies in Multi-Epitope Vaccine Design Against Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. Cell J. Yakhteh 2024, 26, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri-Rachman, E.A.; Kurnianti, A.M.F.; Rizarullah; Setyadi, A.H.; Artarini, A.; Tan, M.I.; Riani, C.; Natalia, D.; Aditama, R.; Nugrahapraja, H. An immunoinformatics approach in designing high-coverage mRNA multi-epitope vaccine against multivariant SARS-CoV-2. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2025, 23, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, R.A.; Heringa, J. An analysis of protein domain linkers: Their classification and role in protein folding. Protein Eng. 2002, 15, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zaro, J.L.; Shen, W.-C. Fusion protein linkers: Property, design and functionality. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy Chichili, V.P.; Kumar, V.; Sivaraman, J. Linkers in the structural biology of protein–protein interactions. Protein Sci. 2013, 22, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, A.; Onozuka, A.; Asahi-Ozaki, Y.; Imai, S.; Hanada, N.; Miwa, Y.; Nisizawa, T. An ingenious design for peptide vaccines. Vaccine 2005, 23, 2322–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aram, C.; Alijanizadeh, P.; Saleki, K.; Karami, L. Development of an ancestral DC and TLR4-inducing multi-epitope peptide vaccine against the spike protein of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 using the advanced immunoinformatics approaches. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 39, 101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Huang, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, D.; Li, J.; Chen, J. Vaccine design based on 16 epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 2115–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Liu, D.X. Proteolytic Activation of the Spike Protein at a Novel RRRR/S Motif Is Implicated in Furin-Dependent Entry, Syncytium Formation, and Infectivity of Coronavirus Infectious Bronchitis Virus in Cultured Cells. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 8744–8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, J.E.; Skarzynski, M.; Therres, J.A.; Ostovitz, J.R.; Zhou, H.; Kreitman, R.J.; Pastan, I. Designing the Furin-Cleavable Linker in Recombinant Immunotoxins Based on Pseudomonas Exotoxin A. Bioconjug. Chem. 2015, 26, 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobó, J.; Kocsis, A.; Dani, R.; Gál, P. Proprotein Convertases and the Complement System. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 958121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, J.; Wang, T.; Nian, R.; Lau, A.; Hoi, K.M.; Ho, S.C.; Gagnon, P.; Bi, X.; Yang, Y. Cleavage efficient 2A peptides for high level monoclonal antibody expression in CHO cells. mAbs 2015, 7, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, J.S.; Jiang, S.; Galimidi, R.P.; Keeffe, J.R.; Bjorkman, P.J. Design and characterization of structured protein linkers with differing flexibilities. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2014, 27, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Park, H.; Son, K.; Kim, H.M.; Jung, Y. Fabrication of rigidity and space variable protein oligomers with two peptide linkers. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 10428–10435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.A.; Drake, V.; Huang, H.-S.; Chiu, S.; Zheng, L. Reprogramming the tumor microenvironment: Tumor-induced immunosuppressive factors paralyze T cells. Oncoimmunology 2015, 4, e1016700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazini, A.; Fisher, K.; Seymour, L. Deregulation of HLA-I in cancer and its central importance for immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, S.S.; Prazeres, D.M.F.; Azevedo, A.M.; Marques, M.P.C. mRNA vaccines manufacturing: Challenges and bottlenecks. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2190–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Hu, Z.; Song, F.; Xu, Y.; Han, X. Lipid nanoparticles: Composition, formulation, and application. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2025, 33, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hald Albertsen, C.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Witzigmann, D.; Lind, M.; Petersson, K.; Simonsen, J.B. The role of lipid components in lipid nanoparticles for vaccines and gene therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 188, 114416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, Y.; Chong, K.; Cui, M.; Cao, Z.; Tang, C.; Tian, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, S. Recent Advances in Lipid Nanoparticles and Their Safety Concerns for mRNA Delivery. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, O.; Zaborova, O.; Shmykov, B.; Ivanov, R.; Reshetnikov, V. Composition of lipid nanoparticles for targeted delivery: Application to mRNA therapeutics. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1466337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.H.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fox, K.; Leung, J.; Strong, C.; Kang, E.; Chen, Y.; Tong, M.; Bommadevara, H.; Jan, E.; et al. Liposomal lipid nanoparticles for extrahepatic delivery of mRNA. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Lymph node targeting for immunotherapy. Immuno-Oncol. Technol. 2023, 20, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojansivu, M.; Barriga, H.M.G.; Holme, M.N.; Morf, S.; Doutch, J.J.; Andaloussi, S.E.; Kjellman, T.; Johnsson, M.; Barauskas, J.; Stevens, M.M. Formulation and Characterization of Novel Ionizable and Cationic Lipid Nanoparticles for the Delivery of Splice-Switching Oligonucleotides. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2419538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaizar, A.; Díaz-Oviedo, D.; Zablowsky, N.; Rissanen, S.; Köbberling, J.; Sun, J.; Steiger, C.; Steigemann, P.; Mann, F.A.; Meier, K. Toward understanding lipid reorganization in RNA lipid nanoparticles in acidic environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2404555121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, F.; Peng, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, D.; Han, T. Exploration of mRNA nanoparticles based on DOTAP through optimization of the helper lipids. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 18, e2300123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Bi, D.; Plantinga, J.A.; Molema, G.; Bussmann, J.; Kamps, J.A.A.M. Development of a Combined Lipid-Based Nanoparticle Formulation for Enhanced siRNA Delivery to Vascular Endothelial Cells. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alameh, M.-G.; Tombácz, I.; Bettini, E.; Lederer, K.; Sittplangkoon, C.; Wilmore, J.R.; Gaudette, B.T.; Soliman, O.Y.; Pine, M.; Hicks, P.; et al. Lipid nanoparticles enhance the efficacy of mRNA and protein subunit vaccines by inducing robust T follicular helper cell and humoral responses. Immunity 2021, 54, 2877–2892.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelkoski, A.E.; Lu, Z.; Sukumar, G.; Dalgard, C.; Said, H.; Alameh, M.-G.; Mitre, E.; Malloy, A.M.W. Ionizable lipid nanoparticles of mRNA vaccines elicit NF-κB and IRF responses through toll-like receptor 4. NPJ Vaccines 2025, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binici, B.; Rattray, Z.; Zinger, A.; Perrie, Y. Exploring the impact of commonly used ionizable and pegylated lipids on mRNA-LNPs: A combined in vitro and preclinical perspective. J. Control. Release 2025, 377, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, D.; Yang, K.; Liang, Z.; Li, M. Ionizable guanidine-based lipid nanoparticle for targeted mRNA delivery and cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadx5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, K.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, N.; Wang, A.; Xue, T.; Wang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Han, L.; Qin, W.; et al. Discovery of Ketal-Ester Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticle with Reduced Hepatotoxicity, Enhanced Spleen Tropism for mRNA Vaccine Delivery. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2404684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, Y.; Pan, X.; Jia, W.; Wu, T.; Zhang, Y. Lipid Nanoparticles Consisting of Sterol-Conjugated Ionizable Lipids Enable Prolonged and Safe mRNA Delivery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 37763–37773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gong, F.; Golubovic, A.; Strilchuk, A.; Chen, J.; Zhou, M.; Dong, S.; Seto, B.; Li, B. Rational design and modular synthesis of biodegradable ionizable lipids via the Passerini reaction for mRNA delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2409572122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini-Kharat, M.; Bremmell, K.E.; Prestidge, C.A. Why do lipid nanoparticles target the liver? Understanding of biodistribution and liver-specific tropism. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2025, 33, 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Wei, T.; Farbiak, L.; Johnson, L.T.; Dilliard, S.A.; Siegwart, D.J. Selective ORgan Targeting (SORT) nanoparticles for tissue specific mRNA delivery and CRISPR/Cas gene editing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, M.A.; Sato, Y.; Elewa, Y.H.A.; Harashima, H. Harnessing the composition of lipid nanoparticles to selectively deliver mRNA to splenic immune cells for anticancer vaccination. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2025, 15, 3626–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Li, Z.; Hou, T.; Shen, Y.; Guo, Z.; Su, Y.-T.; Chen, Z.; Pan, H.; Jiang, W.; Wang, Y. Multicomponent Synthesis of Imidazole-Based Ionizable Lipids for Highly Efficient and Spleen-Selective Messenger RNA Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 15085–15095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.Y.; Witten, J.; Raji, I.O.; Eweje, F.; MacIsaac, C.; Meng, S.; Oladimeji, F.A.; Hu, Y.; Manan, R.S.; Langer, R.; et al. Combinatorial development of nebulized mRNA delivery formulations for the lungs. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kranz, L.M.; Diken, M.; Haas, H.; Kreiter, S.; Loquai, C.; Reuter, K.C.; Meng, M.; Fritz, D.; Vascotto, F.; Hefesha, H.; et al. Systemic RNA delivery to dendritic cells exploits antiviral defence for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 2016, 534, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Qi, S.; Yu, X.; Gao, X.; Yang, K.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, M.; Bai, B.; Feng, Y.; Lu, M.; et al. Development of Mannosylated Lipid Nanoparticles for mRNA Cancer Vaccine with High Antigen Presentation Efficiency and Immunomodulatory Capability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202318515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraresso, F.; Strilchuk, A.W.; Juang, L.J.; Poole, L.G.; Luyendyk, J.P.; Kastrup, C.J. Comparison of DLin-MC3-DMA and ALC-0315 for siRNA Delivery to Hepatocytes and Hepatic Stellate Cells. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 2175–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omata, D.; Kawahara, E.; Munakata, L.; Tanaka, H.; Akita, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Suzuki, R. Effect of Anti-PEG Antibody on Immune Response of mRNA-Loaded Lipid Nanoparticles. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 5672–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Su, D.; Wu, H.; Guo, J. Implications of Anaphylaxis Following mRNA-LNP Vaccines: It Is Urgent to Eliminate PEG and Find Alternatives. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, M.; Drolet, J.-P.; Masse, M.-S.; Filion, C.A.; ALMuhizi, F.; Fein, M.; Copaescu, A.; Isabwe, G.A.C.; Blaquière, M.; Primeau, M.-N. Safety of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with polyethylene glycol allergy: A case series. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 620–625.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Zhu, X.; Huang, F.; Chen, X. Anti-PEG Antibodies and Their Biological Impact on PEGylated Drugs: Challenges and Strategies for Optimization. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Tian, Z.; Wang, J.; Cui, M.; Cao, Z.; Liu, P.; Li, R.; Cai, S.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Y.; et al. Replacing cholesterol and PEGylated lipids with zwitterionic ionizable lipids in LNPs for spleen-specific mRNA translation. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eady6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreadith, R.W.; Viegas, T.X.; Bentley, M.D.; Harris, J.M.; Fang, Z.; Yoon, K.; Dizman, B.; Weimer, R.; Rae, B.P.; Li, X.; et al. Clinical development of a poly(2-oxazoline) (POZ) polymer therapeutic for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease—Proof of concept of POZ as a versatile polymer platform for drug development in multiple therapeutic indications. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 88, 524–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreadith, R.W.; Kim, W.; Smith, K.; Yoon, K.; Weimer, R.; Fang, Z. Overcoming the PEG dilemma with Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) lipids in lipid nanoparticle formulations. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 241, 114392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, V.; Mochida, Y.; Osawa, S.; Tockary, T.A.; Norimatsu, J.; Yokoo, H.; Oba, M.; Uchida, S. Poly(sarcosine) and Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) Tethered To mRNA Provide Stealth Properties To mRNA Polyplexes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 13628–13638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborniak, I.; Macior, A.; Chmielarz, P. Smart, Naturally-Derived Macromolecules for Controlled Drug Release. Molecules 2021, 26, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanata, D.d.M.; Felisberti, M.I. Thermo- and pH-responsive POEGMA-b-PDMAEMA-b-POEGMA triblock copolymers. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 167, 111069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Akiva, E.; Karlsson, J.; Hemmati, S.; Yu, H.; Tzeng, S.Y.; Pardoll, D.M.; Green, J.J. Biodegradable lipophilic polymeric mRNA nanoparticles for ligand-free targeting of splenic dendritic cells for cancer vaccination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2301606120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, E.W.; Tzeng, S.Y.; Sharma, N.; Cutting, G.R.; Green, J.J. Ligand-free biodegradable poly(beta-amino ester) nanoparticles for targeted systemic delivery of mRNA to the lungs. Biomaterials 2025, 313, 122753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.L.; Saravanakumar, G.; Lee, S.; Jang, S.; Kang, S.; Park, M.; Sobha, S.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, S.-M.; Lee, J.-A.; et al. Poly(β-amino ester) polymer library with monomer variation for mRNA delivery. Biomaterials 2025, 314, 122896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Z.; Rehman, K.; Mahmood, A.; Shabbir, M.; Liang, Y.; Duan, L.; Zeng, H. Exosome for mRNA delivery: Strategies and therapeutic applications. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Li, G.; Fu, W.; Lei, C. Exosomes: The next frontier in vaccine development and delivery. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1435426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Liu, X.; Bi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Antony, A.; Lee, D.; Huntoon, K.; Jeong, S.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Adaptive design of mRNA-loaded extracellular vesicles for targeted immunotherapy of cancer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Li, X.; Guan, J.; Yan, S.; Teng, L.; Sun, X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, H.; Tao, W. Potential and development of cellular vesicle vaccines in cancer immunotherapy. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Popowski, K.D.; Zhu, D.; de Juan Abad, B.L.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Lutz, H.; De Naeyer, N.; DeMarco, C.T.; Denny, T.N.; et al. Exosomes decorated with a recombinant SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain as an inhalable COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, M.; Shi, B. Glioblastoma Cell Derived Exosomes as a Potent Vaccine Platform Targeting Primary Brain Cancers and Brain Metastases. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 17309–17322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, T.; Kim, C.-J.; Durikova, H.; Fernandes, S.; Johnson, D.N.; De Rose, R.; et al. mRNA delivery enabled by metal–organic nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, P.; Huang, X.; Ye, N.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Peng, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y. Cytotoxicity of Metal-Based Nanoparticles: From Mechanisms and Methods of Evaluation to Pathological Manifestations. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2106049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppleton, E.; Urbanek, N.; Chakraborty, T.; Griffo, A.; Monari, L.; Göpfrich, K. RNA origami: Design, simulation and application. RNA Biol. 2023, 20, 510–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, S.L.; Sato, Y. Therapeutic Applications of Programmable DNA Nanostructures. Micromachines 2022, 13, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, T.; Qi, X.; Yan, H.; Chang, Y. Therapeutic applications of RNA nanostructures. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 28807–28821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Luo, L.; Hao, Z.; Liu, D. DNA-based nanostructures for RNA delivery. Med. Rev. 2024, 4, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witten, J.; Raji, I.; Manan, R.S.; Beyer, E.; Bartlett, S.; Tang, Y.; Ebadi, M.; Lei, J.; Nguyen, D.; Oladimeji, F.; et al. Artificial intelligence-guided design of lipid nanoparticles for pulmonary gene therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 1790–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, C.; Paunovska, K.; Schrader Echeverri, E.; Loughrey, D.; Da Silva Sanchez, A.J.; Ni, H.; Hatit, M.Z.C.; Lokugamage, M.P.; Kuzminich, Y.; Peck, H.E.; et al. Nanoparticle single-cell multiomic readouts reveal that cell heterogeneity influences lipid nanoparticle-mediated messenger RNA delivery. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Hamilton, A.G.; Zhao, G.; Xiao, Z.; El-Mayta, R.; Han, X.; Gong, N.; Xiong, X.; Xu, J.; Figueroa-Espada, C.G.; et al. High-throughput barcoding of nanoparticles identifies cationic, degradable lipid-like materials for mRNA delivery to the lungs in female preclinical models. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunter, H.M.; Idrisoglu, S.; Singh, S.; Han, D.J.; Ariens, E.; Peters, J.R.; Wong, T.; Cheetham, S.W.; Xu, J.; Rai, S.K.; et al. mRNA vaccine quality analysis using RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.S.; Carlino, M.S.; Khattak, A.; Meniawy, T.; Ansstas, G.; Taylor, M.H.; Kim, K.B.; McKean, M.; Long, G.V.; Sullivan, R.J.; et al. Individualised neoantigen therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab monotherapy in resected melanoma (KEYNOTE-942): A randomised, phase 2b study. Lancet 2024, 403, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainor, J.F.; Patel, M.R.; Weber, J.S.; Gutierrez, M.; Bauman, J.E.; Clarke, J.M.; Julian, R.; Scott, A.J.; Geiger, J.L.; Kirtane, K.; et al. T-cell Responses to Individualized Neoantigen Therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) Alone or in Combination with Pembrolizumab in the Phase 1 KEYNOTE-603 Study. Cancer Discov. 2024, 14, 2209–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, P.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Tian, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, D.; Yao, Z.; Chen, R.; Xiang, G.; Gong, J.; et al. Overcoming cold tumors: A combination strategy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1344272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Ali, H.; Lathia, J.D.; Chen, P. Immunotherapy for glioblastoma: Current state, challenges, and future perspectives. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 1354–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, M.M.; Singh, N.; Ravikumar, P.; Zhang, R.; June, C.H.; Mitchell, M.J. Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated mRNA Delivery for Human CAR T Cell Engineering. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackensen, A.; Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Koenecke, C.; Alsdorf, W.; Wagner-Drouet, E.; Borchmann, P.; Heudobler, D.; Ferstl, B.; Klobuch, S.; Bokemeyer, C.; et al. CLDN6-specific CAR-T cells plus amplifying RNA vaccine in relapsed or refractory solid tumors: The phase 1 BNT211-01 trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2844–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Harmon, J.; Huang, C.; Chen, J.; Xu, Q. In Vitro Engineering Chimeric Antigen Receptor Macrophages and T Cells by Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated mRNA Delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Peng, X.; Yang, S.; Li, X.; Huang, M.; Wei, S.; Zhang, S.; He, G.; Liu, J.; Fan, Q.; et al. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma: Biology, strategy, and immunotherapy. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Han, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, F.; Yi, Z.; Di, L.; Wang, R. Neoantigens combined with in situ cancer vaccination induce personalized immunity and reshape the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maine, C.J.; Miyake-Stoner, S.J.; Spasova, D.S.; Picarda, G.; Chou, A.C.; Brand, E.D.; Olesiuk, M.D.; Domingo, C.C.; Little, H.J.; Goodman, T.T.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an optimized self-replicating RNA platform for low dose or single dose vaccine applications: A randomized, open label Phase I study in healthy volunteers. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, A.; Gurjar, R.; Kaviraj, S.; Kulkarni, A.; Kumar, D.; Kulkarni, R.; Virkar, R.; Krishnan, J.; Yadav, A.; Baranwal, E.; et al. An Omicron-specific, self-amplifying mRNA booster vaccine for COVID-19: A phase 2/3 randomized trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1363–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yao, W.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Z.; Han, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Xu, P.; et al. Lyophilized mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccines with long-term stability and high antigenicity against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2023, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strategy Category | Specific Approach | Mechanism of Action | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ Cap Structure | Cap-0 (m7GpppN), Cap-1 (m7GpppNm), Cap-2 (m7GpppNmNm); ARCA or co-transcriptional capping (e.g., CleanCap) | Protects mRNA from exonucleases, enhances ribosome recruitment, reduces innate immune sensing | Use of CleanCap to obtain high Cap-1/Cap-2 proportion in therapeutic mRNAs |

| 5′ UTR Design | Optimized 5′ UTR sequences (e.g., human β-globin 5′ UTR) | Increases translation initiation efficiency, reduces ribosomal scanning obstacles | β-globin 5′ UTR found to enhance expression in mRNA vaccine context [37] |

| 3′ UTR Design | Use of high-stability 3′ UTRs (e.g., AES + mtRNR1; human α-globin 3′ UTR) | Improves mRNA stability, lengthens translation window, decreases degradation | AES + mtRNR1 combo used in Moderna/other mRNA vaccines [32,38] |

| Poly(A) Tail Length and Composition | Optimized tail length (~100–150 nt), template-encoded or enzyme-added | Enhances transcript stability, promotes ribosome recycling, improves translation efficiency | Extended poly(A) tail designs in IVT mRNA platforms |

| Coding Sequence (CDS)—Codon and Structure | Codon optimization (CAI, tRNA abundance) + minimization of strong 5′ secondary structure | Boosts translation efficiency, reduces ribosomal pausing, improves expression and stability | Use of mRNA folding algorithms for codon/structure optimization [39] |

| Combined Structural Design | Integrated optimization of cap + 5′ UTR + CDS + 3′ UTR + poly(A) | Synergistic effect: enhanced translation, prolonged half-life, reduced unwanted innate activation. | Next-gen mRNA vaccine platforms leveraging full sequence engineering. |

| Linker Category | Specific Sequences | Processing Mechanism | Functional Advantages | Clinical Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible spacers | GGGGS, G4S variants | Non-specific spacing | Prevents steric hindrance | General epitope separation | [88,89,90] |

| Proteasome-sensitive | AAY, LKM, | Proteasomal cleavage | Enhanced MHC-I generation | Class I epitope processing | [91,92,93] |

| Furin-cleavable | RXXR, RAKR, RRRR | Furin protease recognition | Alternative processing pathway | Golgi-based processing | [94,95,96] |

| 2A peptides | T2A, E2A, P2A | Ribosomal skipping | Discrete protein generation | Multi-protein constructs | [97] |

| Cathepsin-sensitive | Specific dipeptides, KK | Lysosomal processing | MHC-II pathway targeting | Class II epitope generation | [91] |

| Flexible + cleavable | GGGGS-EAAAK-GGGGS | Combined mechanisms | Optimal spacing and processing | Balanced epitope liberation | [98,99] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roy, O.; Anderson, K.S. Engineering Anti-Tumor Immunity: An Immunological Framework for mRNA Cancer Vaccines. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1222. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121222

Roy O, Anderson KS. Engineering Anti-Tumor Immunity: An Immunological Framework for mRNA Cancer Vaccines. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1222. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121222

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoy, Olivia, and Karen S. Anderson. 2025. "Engineering Anti-Tumor Immunity: An Immunological Framework for mRNA Cancer Vaccines" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1222. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121222

APA StyleRoy, O., & Anderson, K. S. (2025). Engineering Anti-Tumor Immunity: An Immunological Framework for mRNA Cancer Vaccines. Vaccines, 13(12), 1222. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121222