Mapping Eight Decades of Vaccination Social Science: Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Source and Search Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Overview

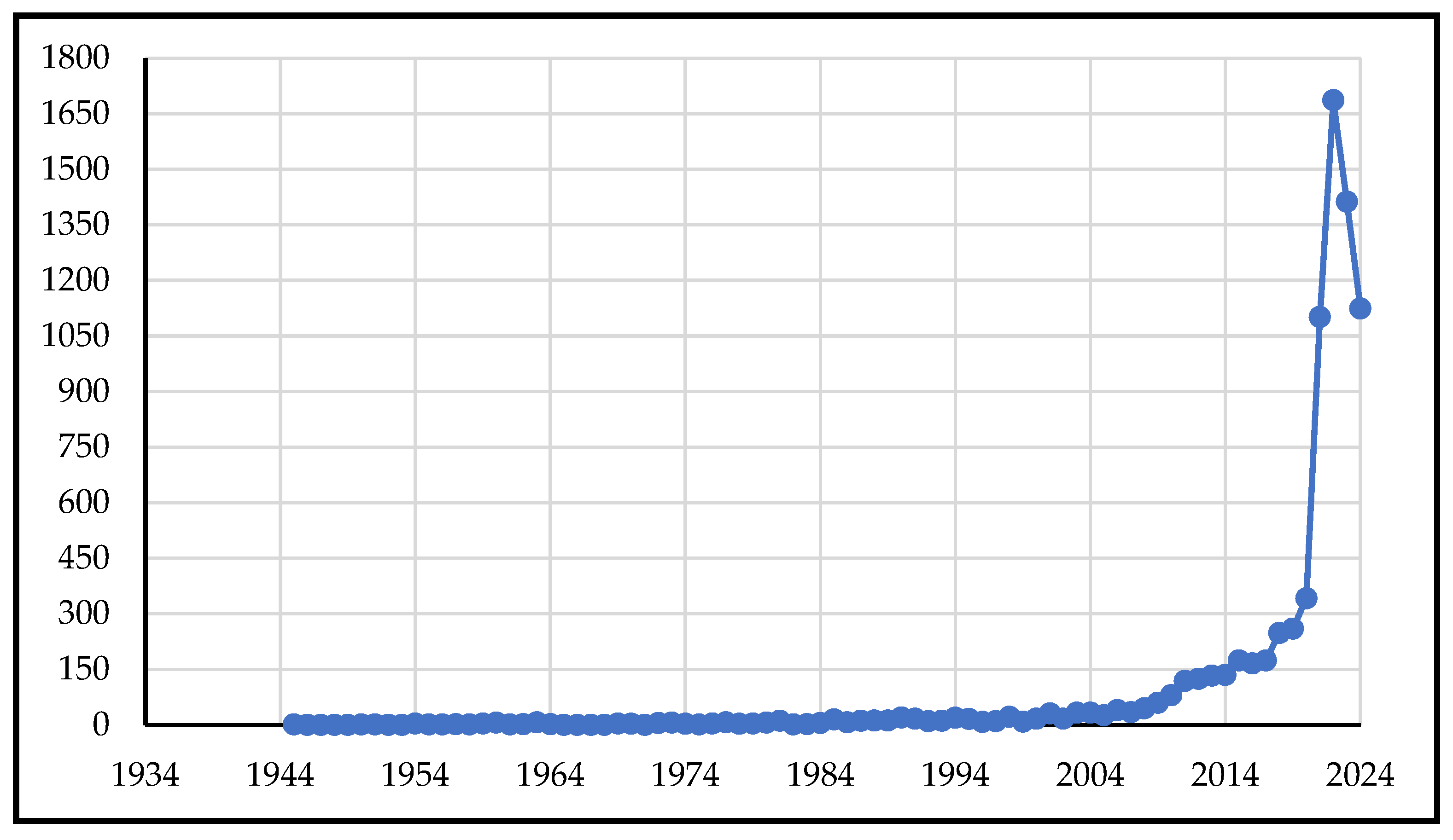

3.2. Publication Trends over Time

3.3. Institutional Distribution of Publications

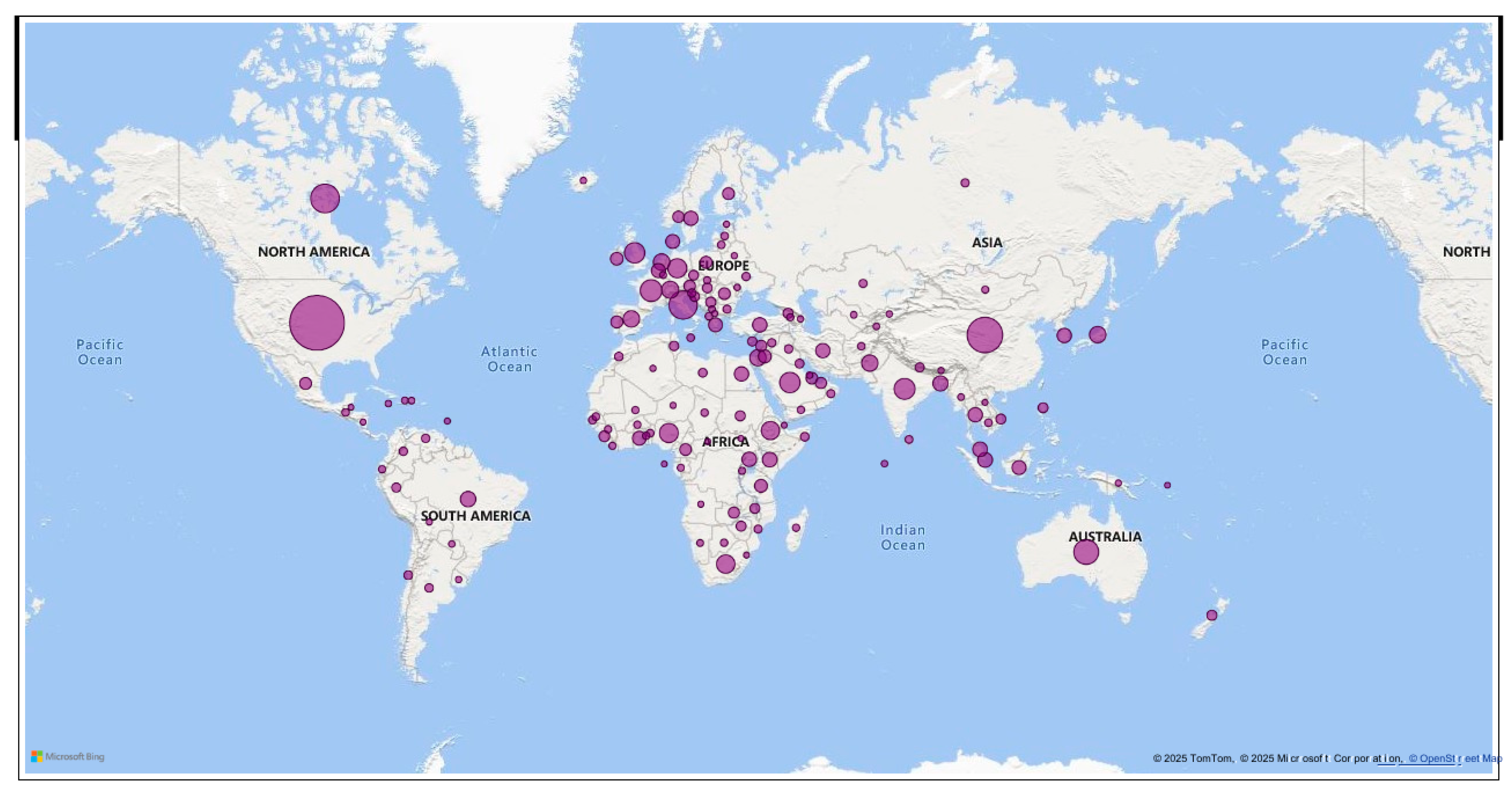

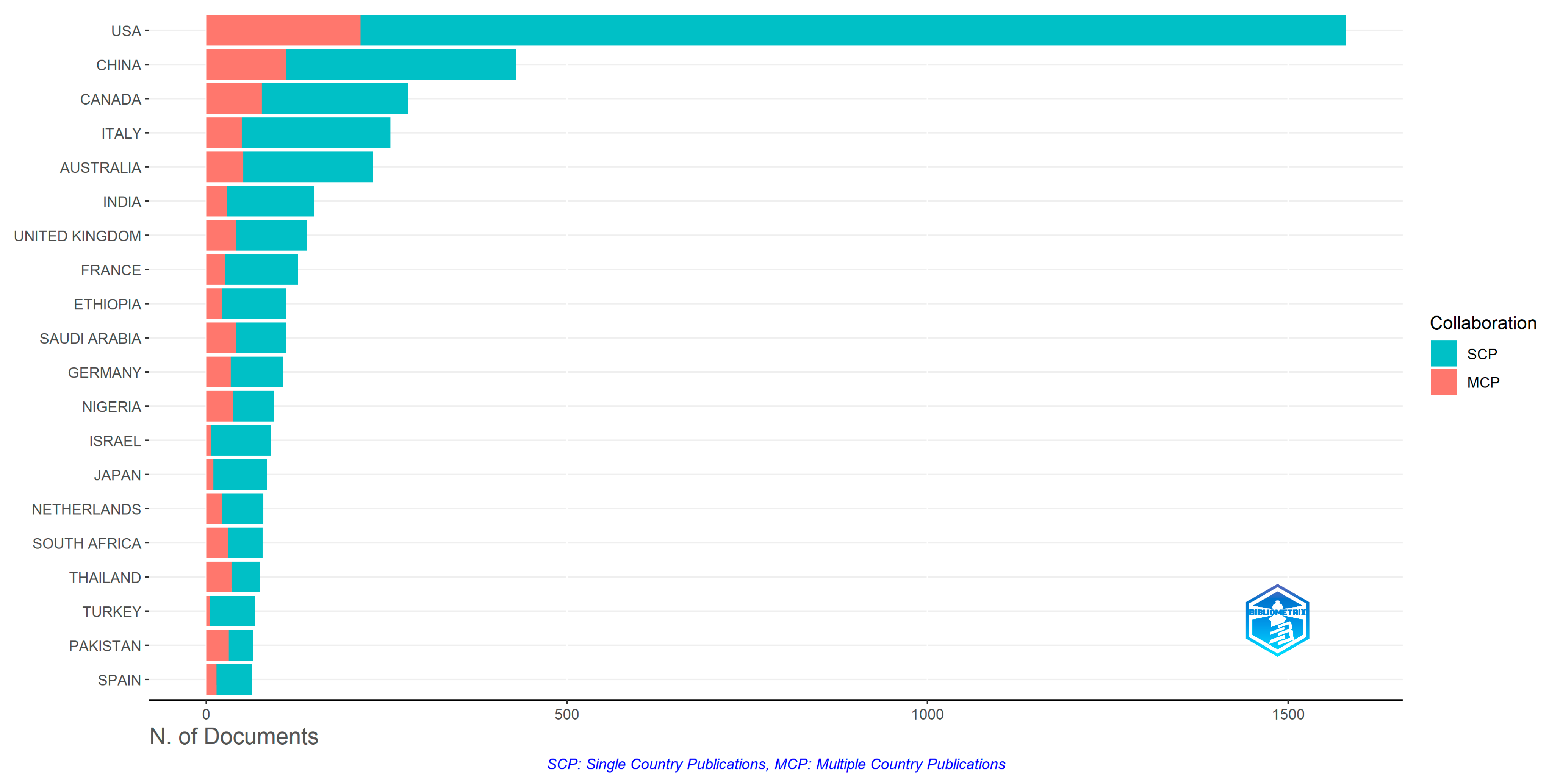

3.4. Geographical Distribution of Publications on Vaccination Social Science

3.5. Author Productivity Analysis

3.6. Shifting Thematic Priorities in Vaccination Social Science Across Three Eras

4. Discussion

Implications for Policy and Research

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shattock, A.J.; Johnson, H.C.; Sim, S.Y.; Carter, A.; Lambach, P.; Hutubessy, R.C.W.; Thompson, K.M.; Badizadegan, K.; Lambert, B.; Ferrari, M.J.; et al. Contribution of Vaccination to Improved Survival and Health: Modelling 50 Years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. Lancet 2024, 403, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S.Y.; Watts, E.; Constenla, D.; Brenzel, L.; Patenaud, B.N. Return on Investment from Immunization against 10 Pathogens in 94 Low-and Middle-Income Countries, 2011–2030. Health Aff. 2020, 39, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Understanding the Behavioural and Social Drivers of Vaccine Uptake: WHO Position Paper—May 2022. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2022, 97, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Rothman, A.J.; Leask, J.; Kempe, A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science Into Action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interes. 2017, 18, 149–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.K.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Dubé, E.; Verger, P.; Attwell, K. Context Matters: How to Research Vaccine Attitudes and Uptake after the COVID-19 Crisis. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2367268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piltch-Loeb, R.; Diclemente, R. The Vaccine Uptake Continuum: Applying Social Science Theory to Shift Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2020, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Ahmed, N.; Shafiq, M.; Elharake, J.A.; James, E.; Nyhan, K.; Paintsil, E.; Melchinger, H.C.; Team, Y.B.I.; Malik, F.A.; et al. Behavioral Interventions for Vaccination Uptake: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 65–70. ISBN 9781800372122. [Google Scholar]

- Smallpox. A Great and Terrible Scourge. Available online: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/smallpox/sp_threat.html (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Obadare, E. A Crisis of Trust: History, Politics, Religion and the Polio Controversy in Northern Nigeria. Patterns Prejud. 2005, 39, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Xue, L.; Shorten, B. Decoding COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Using Multiple Regression Analysis with Socioeconomic Values. Proc. Int. Conf. Adv. Inf. Netw. Appl. 2023, 655, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagovetz, M.; Momchilov, K.; Blank, L.; Khorsandi, J. Global COVID-19 Vaccination Challenges: Inequity of Access and Vaccine Hesitancy. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2025, 6, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Gakidou, E.; Murray, C.J.L. The Vaccine-Hesitant Moment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, H.; Attwell, K.; Danchin, M.; Marshall, H.; Corben, P.; Leask, J. Vaccine Hesitancy, Refusal and Access Barriers: The Need for Clarity in Terminology. Vaccine 2018, 36, 6556–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betsch, C.; Böhm, R.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Butler, R.; Chapman, G.B.; Haase, N.; Herrmann, B.; Igarashi, T.; Kitayama, S.; Korn, L.; et al. Improving Medical Decision Making and Health Promotion through Culture-Sensitive Health Communication: An Agenda for Science and Practice. Med. Decis. Mak. 2016, 36, 811–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwell, K.; Rizzi, M.; Paul, K. Consolidating a Research Agenda for Vaccine Mandates. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 40, 7353–7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Sane, M.; Vanderslott, S.; Rohan, H.; Enria, L. Social Science in Humanitarian Action Platform Key Considerations: Using Social and Behavioural Science to Inform the Use of Vaccines During Health Emergencies Key Considerations; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2025; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Büyükkidik, S. A Bibliometric Analysis: A Tutorial for the Bibliometrix Package in R Using IRT Literature. J. Meas. Eval. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 13, 164–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubMed Overview. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/about/ (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Inf. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E. The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguavoen, A.; Larson, H.J.; Chinye-Nwoko, F.; Ojeniyi, T. Reducing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Improving Vaccine Uptake in Nigeria. J. Public Health Afr. 2023, 14, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hateftabar, F.; Larson, H.J.; Hateftabar, V. Examining the Effects of Psychological Reactance on COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: Comparison of Two Countries. J. Glob. Health 2022, 12, 5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Tong, Y.; Du, F.; Lu, L.; Zhao, S.; Yu, K.; Piatek, S.J.; Larson, H.J.; Lin, L. Assessing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy, Confidence, and Public Engagement: A Global Social Listening Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Kamarulzaman, A.; El-Mohandes, A. A Survey of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance across 23 Countries in 2022. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, A.; Simas, C.; Larson, H.J. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Its Socio-Demographic and Emotional Determinants: A Multi-Country Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccine 2023, 41, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karafillakis, E.; Van Damme, P.; Hendrickx, G.; Larson, H.J. COVID-19 in Europe: New Challenges for Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy. Lancet 2022, 399, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, E.; Simas, C.; Larson, H.J. An Epidemic of Uncertainty: Rumors, Conspiracy Theories and Vaccine Hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P.J.; Larson, H.; Dubé, È.; Fisher, A. Vaccine Hesitancy: Drivers and How the Allergy Community Can Help. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 3568–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, S.; Wiysonge, C.S. Towards a More Critical Public Health Understanding of Vaccine Hesitancy: Key Insights from a Decade of Research. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpechi, I.G.; Swanepoel, C.R.; Venter, F. Access to Medications and Conducting Clinical Trials in LMICs. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2015, 11, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, C.; Mitchell, G.; Nikles, J. Barriers for Conducting Clinical Trials in Developing Countries—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2018, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpkin, V.; Namubiru-Mwaura, E.; Clarke, L.; Mossialos, E. Investing in Health R&d: Where We Are, What Limits Us, and How to Make Progress in Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; Jarrett, C.; Eckersberger, E.; Smith, D.M.D.; Paterson, P. Understanding Vaccine Hesitancy around Vaccines and Vaccination from a Global Perspective: A Systematic Review of Published Literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2150–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy; World Health Organisation (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Privor-Dumm, L.; Excler, J.L.; Gilbert, S.; Abdool Karim, S.S.; Hotez, P.J.; Thompson, D.; Kim, J.H. Vaccine Access, Equity and Justice: COVID-19 Vaccines and Vaccination. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e011881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu-Jaja, C.; Ndwandwe, D.; Malinga, T.; Mathebula, L.; Mazingisa, A.; Wiysonge, C.S. Vaccine Research Trends in Africa from 2016 to Mid-2024: A Bibliometric Analysis. Vaccines 2025, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description | Results |

|---|---|

| Number of articles | 8005 |

| Sources (Journals, Books, etc.) | 1466 |

| Overall annual growth rate (percentage) | 2% |

| Total number of authors | 33,026 |

| International co-authorships (percentage) | 19.44% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iwu-Jaja, C.; Nkereuwem, O.; Iwu, C.D.; Mazingisa, A.V.; Jaca, A.; Ndwandwe, D.; Wiysonge, C.S. Mapping Eight Decades of Vaccination Social Science: Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111138

Iwu-Jaja C, Nkereuwem O, Iwu CD, Mazingisa AV, Jaca A, Ndwandwe D, Wiysonge CS. Mapping Eight Decades of Vaccination Social Science: Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends. Vaccines. 2025; 13(11):1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111138

Chicago/Turabian StyleIwu-Jaja, Chinwe, Oluwatosin Nkereuwem, Chidozie D. Iwu, Akhona V. Mazingisa, Anelisa Jaca, Duduzile Ndwandwe, and Charles S. Wiysonge. 2025. "Mapping Eight Decades of Vaccination Social Science: Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends" Vaccines 13, no. 11: 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111138

APA StyleIwu-Jaja, C., Nkereuwem, O., Iwu, C. D., Mazingisa, A. V., Jaca, A., Ndwandwe, D., & Wiysonge, C. S. (2025). Mapping Eight Decades of Vaccination Social Science: Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research Trends. Vaccines, 13(11), 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111138