Multilevel Interventions Aimed at Improving HPV Immunization Coverage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Objective

2.3. Literature Search

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Quality Appraisal of Included Studies

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

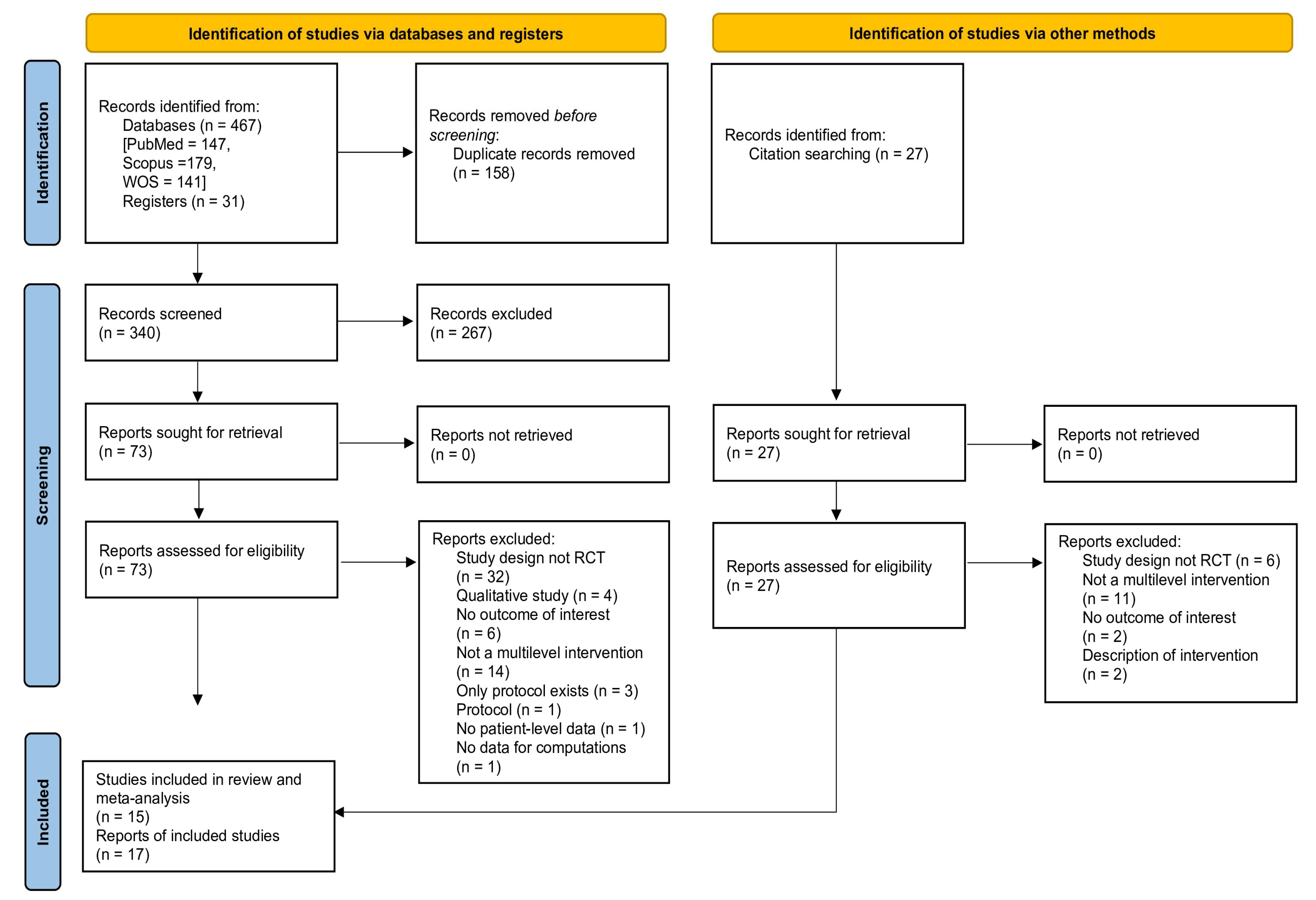

3.1. Literature Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

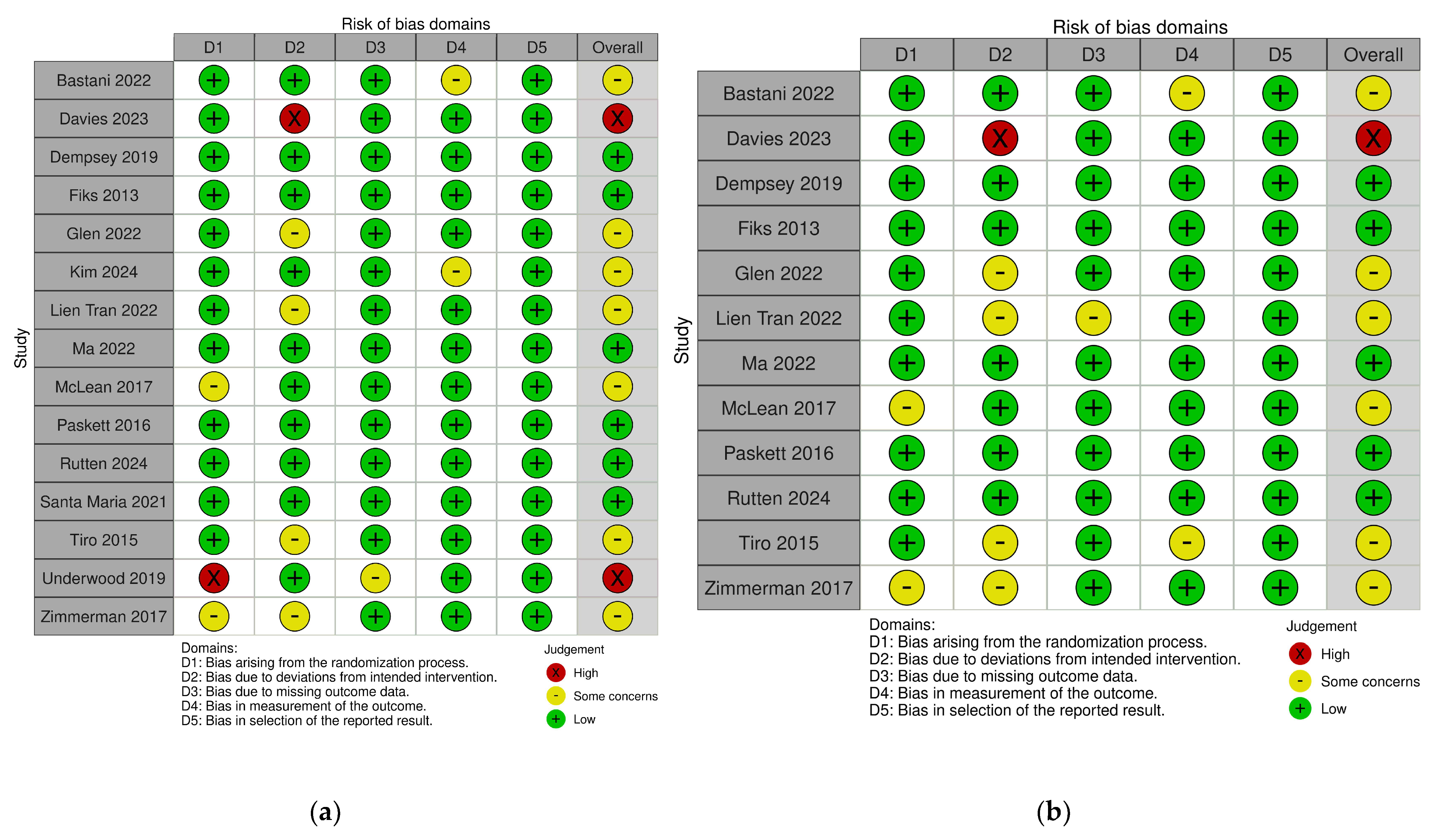

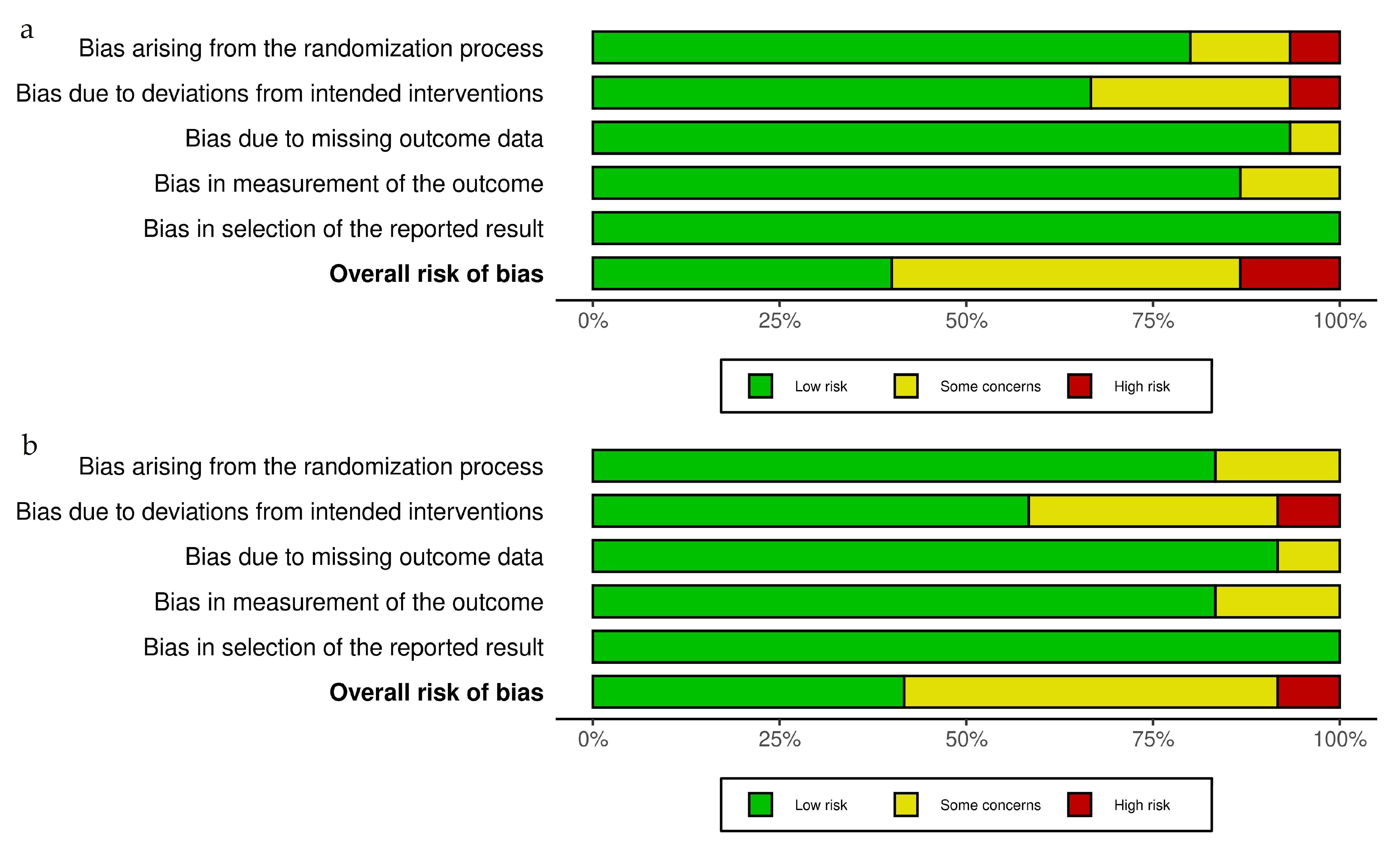

3.3. Risk of Bias of Included Studies

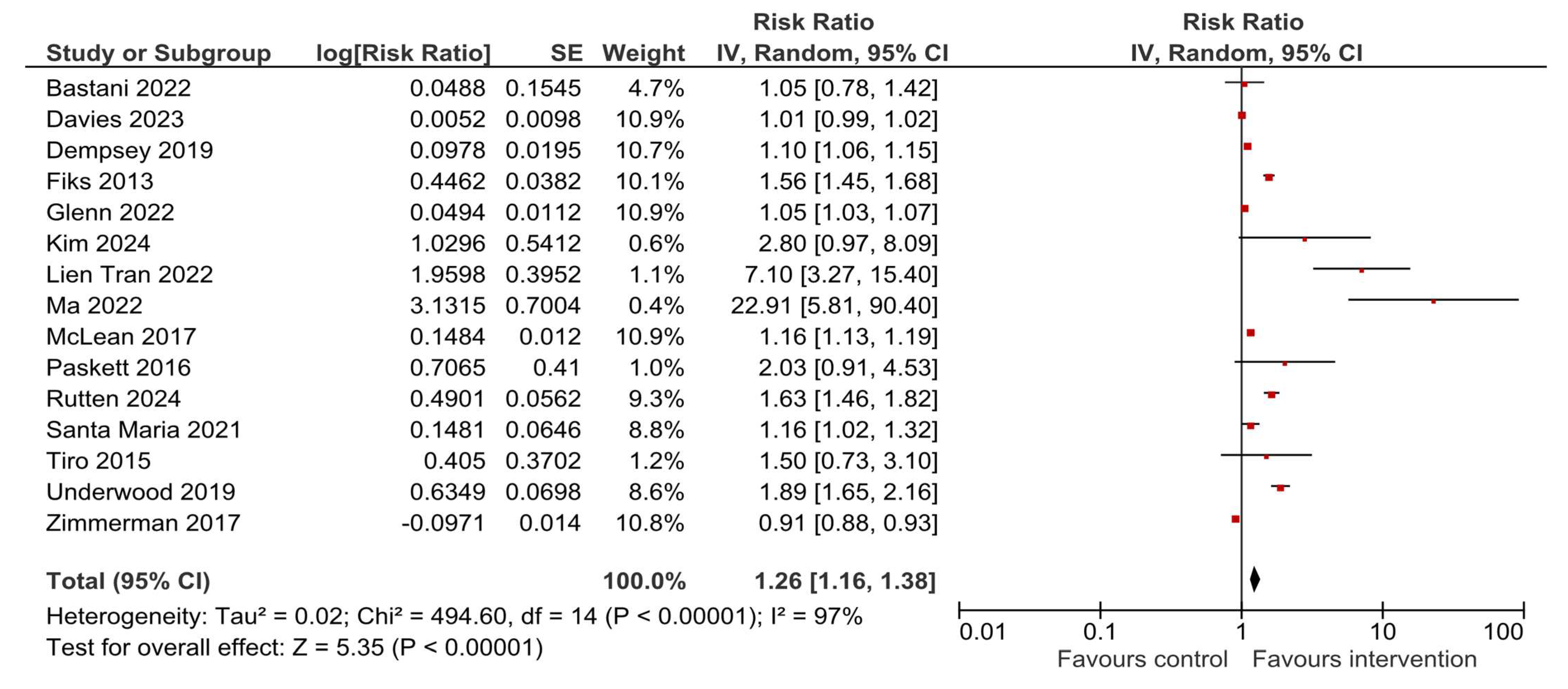

3.4. HPV Vaccination Initiation

3.5. HPV Vaccination Completion

3.6. Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crosbie, E.J.; Einstein, M.H.; Franceschi, S.; Kitchener, H.C. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 2013, 382, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Yin, A.; Zhang, B.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Tang, L.; et al. Global landscape of cervical cancer incidence and mortality in 2022 and predictions to 2030: The urgent need to address inequalities in cervical cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 157, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Martel, C.; Georges, D.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Clifford, G.M. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e180–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper (2022 update). Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2022, 97, 645–672. [Google Scholar]

- IA2030 Global Progress Report 2024. Available online: https://www.immunizationagenda2030.org/images/documents/Immunization_Agenda_2030_Global_Progress_Report_2024_final.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Mavundza, E.J.; Iwu-Jaja, C.J.; Wiyeh, A.B.; Gausi, B.; Abdullahi, L.H.; Halle-Ekane, G.; Wiysonge, C.S. A Systematic Review of Interventions to Improve HPV Vaccination Coverage. Vaccines 2021, 9, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Immunization Coverage. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/immunization-coverage (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Casey, R.M.; Akaba, H.; Hyde, T.B.; Bloem, P. Covid-19 pandemic and equity of global human papillomavirus vaccination: Descriptive study of World Health Organization-Unicef vaccination coverage estimates. BMJ Med. 2024, 3, e000726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reza, S.; Anjum, R.; Khandoker, R.Z.; Khan, S.R.; Islam, M.R.; Dewan, S.M.R. Public health concern-driven insights and response of low- and middle-income nations to the World health Organization call for cervical cancer risk eradication. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 54, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, J.; Harris, M.; Skyers, N.; Bailey, A.; Figueroa, J.P. A Call for Low- and Middle-Income Countries to Commit to the Elimination of Cervical Cancer. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2021, 2, 100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisson, M.; Kim, J.J.; Canfell, K.; Drolet, M.; Gingras, G.; Burger, E.A.; Martin, D.; Simms, K.T.; Bénard, É.; Boily, M.C.; et al. Impact of HPV vaccination and cervical screening on cervical cancer elimination: A comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet 2020, 395, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Fisher, C.B. Multilevel Targets for Promoting Pediatric HPV Vaccination: A Systematic Review of Parent-Centered, Provider-Centered, and Practice-Centered Interventions in HIC and LMIC Settings. Vaccines 2025, 13, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion and Practice, 2nd ed.; NIH Publication No. 05-3896; National Institutes of Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. Available online: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/theory.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Golden, S.D.; Earp, J.A. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskett, E.; Thompson, B.; Ammerman, A.S.; Ortega, A.N.; Marsteller, J.; Richardson, D. Multilevel Interventions To Address Health Disparities Show Promise In Improving Population Health. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 1429–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Liu, Q.M.; Ren, Y.J.; He, P.P.; Wang, S.F.; Gao, F.; Li, L.M.; Community Interventions for Health (CIH) collaboration. A community-based multilevel intervention for smoking, physical activity and diet: Short-term findings from the Community Interventions for Health programme in Hangzhou, China. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2014, 68, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewart-Pierce, E.; Mejía Ruiz, M.J.; Gittelsohn, J. “Whole-of-Community” Obesity Prevention: A Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Multilevel, Multicomponent Interventions. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2016, 5, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, E.M.; Staab, E.M.; Deckard, A.N.; Uranga, S.I.; Thomas, N.C.; Wan, W.; Karter, A.J.; Huang, E.S.; Peek, M.E.; Laiteerapong, N. Effectiveness of Multilevel and Multidomain Interventions to Improve Glycemic Control in U.S. Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, A.F.; Pyrznawoski, J.; Lockhart, S.; Barnard, J.; Campagna, E.J.; Garrett, K.; Fisher, A.; Dickinson, L.M.; O’Leary, S.T. Effect of a Health Care Professional Communication Training Intervention on Adolescent Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, e180016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paskett, E.D.; Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Tatum, C.M.; Reiter, P.L.; Peng, J.; Bernardo, B.M.; Weier, R.C.; Richardson, M.S.; Katz, M.L. Results of a Multilevel Intervention Trial to Increase Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Uptake among Adolescent Girls. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastani, R.; Glenn, B.A.; Singhal, R.; Crespi, C.M.; Nonzee, N.J.; Tsui, J.; Chang, L.C.; Herrmann, A.K.; Taylor, V.M. Increasing HPV Vaccination among Low-Income, Ethnic Minority Adolescents: Effects of a Multicomponent System Intervention through a County Health Department Hotline. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; Marshall, H.S.; Brotherton, J.M.L.; McCaffery, K.; Kang, M.; Macartney, K.; Garland, S.M.; Kaldor, J.; Zimet, G.; Skinner, S.R.; et al. Complex intervention to promote human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake in school settings: A cluster-randomized trial. Prev. Med. 2023, 172, 107542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res. Syn. Meth. 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.5 (updated August 2024); Cochrane: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, M.B.; VanderWeele, T.J. Sensitivity analysis for publication bias in meta-analyses. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2020, 69, 1091–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Review Manager (RevMan), version 5.4.1. Computer program. The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014.

- Fiks, A.G.; Grundmeier, R.W.; Mayne, S.; Song, L.; Feemster, K.; Karavite, D.; Hughes, C.C.; Massey, J.; Keren, R.; Bell, L.M.; et al. Effectiveness of decision support for families, clinicians, or both on HPV vaccine receipt. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, B.A.; Nonzee, N.J.; Herrmann, A.K.; Crespi, C.M.; Haroutunian, G.G.; Sundin, P.; Chang, L.C.; Singhal, R.; Taylor, V.M.; Bastani, R. Impact of a Multi-Level, Multi-Component, System Intervention on HPV Vaccination in a Federally Qualified Health Center. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 1952–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Kornides, M.; Chittams, J.; Waas, R.; Duncan, R.; Teitelman, A.M. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intervention to Promote HPV Uptake Among Young Women Who Attend Subsidized Clinics. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2024, 53, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, P.L.; Chirpaz, E.; Boukerrou, M.; Bertolotti, A. PROM SSCOL-Impact of a Papillomavirus Vaccination Promotion Program in Middle Schools to Raise the Vaccinal Coverage on Reunion Island. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.X.; Zhu, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhai, S.; Lin, T.R.; Zambrano, C.; Siu, P.; Lai, S.; Wang, M.Q. A Multilevel Intervention to Increase HPV Vaccination among Asian American Adolescents. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, H.Q.; VanWormer, J.J.; Chow, B.D.W.; Birchmeier, B.; Vickers, E.; DeVries, E.; Meyer, J.; Moore, J.; McNeil, M.M.; Stokley, S.; et al. Improving Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Use in an Integrated Health System: Impact of a Provider and Staff Intervention. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finney Rutten, L.J.; Griffin, J.M.; St Sauver, J.L.; MacLaughlin, K.; Austin, J.D.; Jenkins, G.; Herrin, J.; Jacobson, R.M. Multilevel Implementation Strategies for Adolescent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Maria, D.; Markham, C.; Misra, S.M.; Coleman, D.C.; Lyons, M.; Desormeaux, C.; Cron, S.; Guilamo-Ramos, V. Effects of a randomized controlled trial of a brief, student-nurse led, parent-based sexual health intervention on parental protective factors and HPV vaccination uptake. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiro, J.A.; Sanders, J.M.; Pruitt, S.L.; Stevens, C.F.; Skinner, C.S.; Bishop, W.P.; Fuller, S.; Persaud, D. Promoting HPV Vaccination in Safety-Net Clinics: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, N.L.; Gargano, L.M.; Sales, J.; Vogt, T.M.; Seib, K.; Hughes, J.M. Evaluation of Educational Interventions to Enhance Adolescent Specific Vaccination Coverage. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, R.K.; Moehling, K.K.; Lin, C.J.; Zhang, S.; Raviotta, J.M.; Reis, E.C.; Humiston, S.G.; Nowalk, M.P. Improving adolescent HPV vaccination in a randomized controlled cluster trial using the 4 Pillars™ practice Transformation Program. Vaccine 2017, 35, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Escoffery, C.; Petagna, C.; Agnone, C.; Perez, S.; Saber, L.B.; Ryan, G.; Dhir, M.; Sekar, S.; Yeager, K.A.; Biddell, C.B.; et al. A systematic review of interventions to promote HPV vaccination globally. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, F.A.; Padhani, Z.A.; Salam, R.A.; Aliani, R.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K.; Bhutta, Z.A. Interventions to Improve Immunization Coverage Among Children and Adolescents: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021053852D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, S.A.; Mullen, P.D.; Lopez, D.M.; Savas, L.S.; Fernández, M.E. Factors associated with adolescent HPV vaccination in the U.S.: A systematic review of reviews and multilevel framework to inform intervention development. Prev. Med. 2020, 131, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, B.W.; Panozzo, C.A.; Moss, J.L.; Reiter, P.L.; Whitesell, D.H.; Brewer, N.T. Evaluation of an intervention providing HPV vaccine in schools. Am. J. Health Behav. 2014, 38, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandeying, N.; Khantee, P.; Puetpaiboon, S.; Thongseiratch, T. Gender-neutral vs. gender-specific strategies in school-based HPV vaccination programs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1460511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, R.A.; Chamberlain, A.; Mathewson, K.; Salmon, D.A.; Omer, S.B. Practice-, Provider-, and Patient-level interventions to improve preventive care: Development of the P3 Model. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 11, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, P.D.; Gross, C.P.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Taplin, S.H. Multilevel interventions: Study design and analysis issues. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2012, 2012, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Durantini, M.R.; Calabrese, C.; Sanchez, F.; Albarracin, D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of strategies to promote vaccination uptake. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 1689–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSherry, L.A.; Dombrowski, S.U.; Francis, J.J.; Murphy, J.; Martin, C.M.; O’Leary, J.J.; Sharp, L.; ATHENS Group. ‘It’s a can of worms’: Understanding primary care practitioners’ behaviours in relation to HPV using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadzange, E.E.; Peeters, A.; Joore, M.A.; Kimman, M.L. The effectiveness of health education interventions on cervical cancer prevention in Africa: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, D.E.; Bolio, A.; Guillaume, D.; Sidibe, A.; Morgan, C.; Karafillakis, E.; Holloway, M.; Van Damme, P.; Limaye, R.; Vorsters, A. Planning, implementation, and sustaining high coverage of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination programs: What works in the context of low-resource countries? Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1112981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilkey, M.B.; McRee, A.L. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: A systematic review. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016, 12, 1454–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year [Ref.] | Study Location and Duration/Period | N Total Intervention | N Total Control | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bastani, 2022 [23] | USA, November 2013–June 2016 | 138 caregivers | 100 caregivers | HPV vaccine initiation: OR = 1.09 (0.52–2.29), p = 0.83 HPV vaccine completion: OR = 1.15 (0.49–2.66), p = 0.75 |

| Davies, 2023 [24] | Australia, 2013–2015 | 21 schools with a total of 3805 students | 19 schools with a total of 3162 students | HPV vaccine dose 1: Difference 0.8% (−1.4, 3.0), p = 0.47 HPV vaccine dose 3: Difference 0.5% (−2.6, 3.7), p = 0.74 |

| Dempsey, 2019 [21] | USA, February 2015–January 2016 | 8 practices, 76 health professionals, 15,678 patients | 8 practices, 112 health professionals, 15,592 patients | HPV vaccine initiation difference in differences: OR = 1.46 (1.31–1.62) HPV vaccine completion difference in differences: OR = 1.56 (1.27–1.92) |

| Fiks, 2013 [32] | USA, 2010–2011 | 11 practices, 5561 participants—adolescent girls | 11 practices, 5688 participants—adolescent girls | HPV dose 1: HR = 1.6 (1.2–2.1), p = 0.001 HPV dose 3: HR = 1.5 (1.3–1.7), p < 0.001 |

| Glenn, 2022 [33] | USA, January 2015–March 2017 | 4 clinics, 5988 patients | 4 clinics, 8750 patients | Difference-in-differences in quarterly change: HPV vaccine initiation: 0.75 (SE 0.15), p < 0.001 HPV vaccine completion: 0.17 (SE 0.14), p = 0.21 |

| Kim, 2024 [34] | USA | 12 women | 14 women | HPV vaccine initiation: OR = 7.0 (1.07–46), p = 0.04 |

| Tran, 2022 [35] | France, October 2020–June 2021 | 245 students | 259 students | HPV vaccine initiation: 19.2% vs. 2.7%, p < 0.001 HPV vaccine completion: 24.1% vs. 2.4%, p < 0.001 |

| Ma, 2022 [36] | USA, no information on period | 110 parents and guardians | 70 parents and guardians | HPV vaccine initiation: 65.45% vs. 2.9% HPV vaccine completion: 65.45% vs. 0.0% |

| McLean, 2017 [37] | USA, February 2015–March 2016 | 9 primary care departments, 16,041 adolescents | 34 primary care departments, 8617 adolescents | HPV vaccine initiation in 11–12 years old 59.3% vs. 44.5% and in 13–17 years old 61.7% vs. 55.4% HPV vaccine completion in 11–12 years old 52.7% vs. 52.3% and in 13–17 years old 71.9% vs. 66.9% |

| Paskett, 2016 [22] | USA, 2010–2015 | 6 counties, 10 clinics, 57 providers, 174 parents of girls | 6 counties, 12 clinics, 62 providers, 163 parents of girls | HPV vaccine initiation: 13.1% vs. 6.5%, p = 0.003 HPV vaccine completion: 50.0% vs. 66.7%, p = 0.524 |

| Finney Rutten, 2024 [38] | USA, April 2018–September 2022 | 2660 patients | 3572 patients | HPV vaccine initiation: OR = 2.01 (1.34–3.04), p = 0.01 HPV vaccine completion: OR = 1.91 (1.08–3.39), p = 0.004 |

| Santa Maria, 2021 [39] | USA, 2015–2018 | 261 parents, 255 youth | 258 parents, 253 youth | HPV vaccination initiation: 70.3% vs. 60.6%, p = 0.02 No difference for HPV vaccine completion |

| Tiro, 2015 [40] | USA, February–December 2011 | 410 female adolescents | 404 female adolescents | HPV vaccine dose 1: OR = 1.43 (1.02–2.02), p < 0.05 HPV vaccine dose 3: OR = 1.99 (1.16–3.45), p < 0.05 |

| Underwood, 2019 [41] | USA, 2011–2013 | 690 students | 777 students | HPV vaccine—at least one dose: 50.1% vs. 39.5% |

| Zimmerman, 2017 [42] | USA, January 2013–March 2015 | 4942 | 5919 | HPV vaccine series initiation: 62.7% vs. 69.1% HPV vaccine series completion: 44.1% vs. 50.0% |

| Item | Outcome | Analysis Model | Heterogeneity | Overall Estimate RR with 95% CI | Test for Overall Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | p | Z | p | ||||

| Low risk of bias | HPV vaccination initiation | Random | 96% | <0.00001 | 1.48 (1.18–1.86) | 3.35 | 0.0008 |

| HPV vaccination completion | Random | 95% | <0.00001 | 1.27 (1.09–1.48) | 3.09 | 0.002 | |

| Comparator being usual care | HPV vaccination initiation | Random | 98% | <0.00001 | 1.28 (1.16–1.43) | 4.6 | <0.00001 |

| HPV vaccination completion | Random | 98% | <0.00001 | 1.14 (1.02–1.29) | 2.22 | 0.03 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ilic, I.; Jakovljevic, V.; Gajdacs, M.; Paulik, E.; Ilic, M. Multilevel Interventions Aimed at Improving HPV Immunization Coverage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13101001

Ilic I, Jakovljevic V, Gajdacs M, Paulik E, Ilic M. Multilevel Interventions Aimed at Improving HPV Immunization Coverage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines. 2025; 13(10):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13101001

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlic, Irena, Vladimir Jakovljevic, Mario Gajdacs, Edit Paulik, and Milena Ilic. 2025. "Multilevel Interventions Aimed at Improving HPV Immunization Coverage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Vaccines 13, no. 10: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13101001

APA StyleIlic, I., Jakovljevic, V., Gajdacs, M., Paulik, E., & Ilic, M. (2025). Multilevel Interventions Aimed at Improving HPV Immunization Coverage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines, 13(10), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13101001