Influenza Vaccination during Pregnancy: A Descriptive Study of the Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices of Mexican Gynecologists and Family Physicians

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

Survey Design and Delivery

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keilman, L.J. Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Nurs. Clin. North Am. 2019, 54, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nypaver, C.; Dehlinger, C.; Carter, C. Influenza and Influenza Vaccine: A Review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2021, 66, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, D.; Geraci, J.; Winkup, J.; Gessner, B.D.; Ortiz, J.R.; Loeb, M. Pregnancy as a risk factor for severe outcomes from influenza virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Vaccine 2017, 35, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, S.A.; Jamieson, D.J. Influenza and Pregnancy: No Time for Complacency. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, A.K.; Håberg, S.E.; Fell, D.B. Current Perspectives on Maternal Influenza Immunization. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2019, 6, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozde Kanmaz, H.; Erdeve, O.; Suna Oğz, S.; Uras, N.; Çelen, Ş.; Korukluoglu, G.; Zergeroglu, S.; Kara, A.; Dilmen, U. Placental Transmission of Novel Pandemic Influenza a Virus. Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 2011, 30, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.N.; Yu, F.Y.; Xu, Q.; Gu, J. Tropism and Infectivity of Pandemic Influenza A H1N1/09 Virus in the Human Placenta. Viruses 2022, 14, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, M.; Kurinczuk, J.J.; Spark, P.; Brocklehurst, P.; Knight, M.; UKOSS. Perinatal outcomes after maternal 2009/H1N1 infection: National cohort study. BMJ 2011, 342, d3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Gao, H.L.; Yao, W.Z.; Gao, H.; Cui, Y. Early clinical characteristics and pregnancy outcomes of patients with influenza A (H1N1) infection requiring mechanical ventilation during pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 33, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etti, M.; Calvert, A.; Galiza, E.; Lim, S.; Khalil, A.; Le Doare, K.; Heath, P.T. Maternal vaccination: A review of current evidence and recommendations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Correa-Silva, S.; Palmeira, P.; Carneiro-Sampaio, M. Maternal vaccination as an additional approach to improve the protection of the nursling: Anti-infective properties of breast milk. Clinics 2022, 77, 100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raut, S.; Apte, A.; Srinivasan, M.; Dudeja, N.; Dayma, G.; Sinha, B.; Bavdekar, A. Determinants of maternal influenza vaccination in the context of low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.G.; Kwong, J.C.; Regan, A.K.; Katz, M.; Drews, S.J.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Klein, N.P.; Chung, H.; Effler, P.V.; Feldman, B.S.; et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Influenza-associated Hospitalizations During Pregnancy: A Multi-country Retrospective Test Negative Design Study, 2010–2016. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 68, 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz, F.M. Influenza Vaccination During Pregnancy Can Protect Women Against Hospitalization Across Continents. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 68, 1454–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia, M.D.; Sow, S.; Tamboura, B.; Tégueté, I.; Pasetti, M.F.; Kodio, M.; Onwuchekwa, U.; Tennant, S.M.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Coulibaly, F.; et al. Maternal immunisation with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine for prevention of influenza in infants in Mali: A prospective, active-controlled, observer-blind, randomised phase 4 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1026–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhi, S.A.; Cutland, C.L.; Kuwanda, L.; Weinberg, A.; Hugo, A.; Jones, S.; Adrian, P.V.; van Niekerk, N.; Treurnicht, F.; Ortiz, J.R.; et al. Influenza Vaccination of Pregnant Women and Protection of Their Infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Influenza Vaccination Coverage, Pregnant Persons, United States. CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/dashboard/vaccination-coverage-pregnant.html (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Simas, C.; Larson, H.J.; Paterson, P. Saint Google, now we have information: A qualitative study on narratives of trust and attitudes towards maternal vaccination in Mexico City and Toluca. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud, Gobierno de México. Cobertura de Vacunación Contra Influenza es de 62% en Promedio. 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/259-cobertura-de-vacunacion-contra-influenza-es-de-62-en-promedio?idiom=es. (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Vacunacion en la Embarazada—Mexico Gobierno General—Guia de Reference Rapida. Available online: http://www.cenetec-difusion.com/CMGPC/IMSS-580-12/RR.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Kuri-Morales, P.A.; del Castillo-Flores, G.D.; Castañeda-Prado, A.; Pacheco-Montes, S.R. Clinical-epidemiological profile of deaths from influenza with a history of timely vaccination, Mexico 2010–2018. Gac. Med. Mex. 2020, 155, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo-Valdivia, B.; Mendoza-Alvarado, L.R.; Palma-Coca, O.; Hernández-Ávila, M.; Téllez-Rojo Solís, M.M. Encuesta Nacional de Cobertura de Vacunación (influenza, neumococo y tétanos) en adultos mayores de 60 años en México. Salud Pública México 2012, 54, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guia Practica Clinica. Control Prenatal con Atención Centrada en la Paciente. Available online: https://www.imss.gob.mx/sites/all/statics/guiasclinicas/028GER.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Likert-Scale (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Hurtado-Ochoterena, C.A.; Matias-Juan, N.A. Historia de la vacunación en Mexico. Vac. Hoy Rev. Mex. Puer. Pediatr. 2005, 13, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Velandia-González, M.; Vilajeliu, A.; Contreras, M.; Trumbo, S.P.; Pacis, C.; Ropero, A.M.; Ruiz-Matus, C. Monitoring progress of maternal and neonatal immunization in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccine 2021, 39, B55–B63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maertens, K.; Braeckman, T.; Top, G.; Van Damme, P.; Leuridan, E. Maternal pertussis and influenza immunization coverage and attitude of health care workers towards these recommendations in Flanders, Belgium. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5785–5791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishram, B.; Letley, L.; Van Hoek, A.J.; Silverton, L.; Donovan, H.; Adams, C.; Green, D.; Edwards, A.; Yarwood, J.; Bedford, H.; et al. Vaccination in pregnancy: Attitudes of nurses, midwives and health visitors in England. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2017, 14, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arao, R.F.; Rosenberg, K.D.; McWeeney, S.; Hedberg, K. Influenza Vaccination of Pregnant Women: Attitudes and Behaviors of Oregon Physician Prenatal Care Providers. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, K.F.; Menning, L.; Lambach, P. The faces of influenza vaccine recommendation: A Literature review of the determinants and barriers to health providers’ recommendation of influenza vaccine in pregnancy. Vaccine 2020, 38, 4805–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Tremolati, E.; Bellasio, M.; Chiarelli, G.; Marchisio, P.; Tiso, B.; Mosca, F.; Pardi, G.; Principi, N. Attitudes and knowledge regarding influenza vaccination among hospital health workers caring for women and children. Vaccine 2007, 25, 5283–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabadi, A.; Dodds, L.; MacDonald, N.E.; Top, K.A.; Benchimol, E.I.; Kwong, J.C.; Ortiz, J.R.; Sprague, A.E.; Walsh, L.K.; Wilson, K.; et al. Association of Maternal Influenza Vaccination During Pregnancy with Early Childhood Health Outcomes. JAMA 2021, 325, 2285–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisa, A.; Milligan, S.; Quinn, A.; Boulter, D.; Johnston, J.; Treanor, C.; Bradley, D.T. Vaccination against pertussis and influenza in pregnancy: A qualitative study of barriers and facilitators. Public Health 2018, 162, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics of Study Population (n = 206) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medical Specialty | OBGYNs | 98 (47.6%) |

| FPs | 108 (52.4%) | |

| Gender | Female | 131 (63.6%) |

| Male | 75 (36.4%) | |

| Geography/State | Baja California | 134 (65.4%) |

| Mexico City | 20 (9.3%) | |

| Other states | 52 (25.3%) | |

| Primary Medical Practice Institution | Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) | 76 (37%) |

| Private Sector | 69 (34%) | |

| Secretary of Health (SSa) Sector | 31 (15%) | |

| 2 or more institutions | 30 (14.5%) | |

| Years of work experience | 1–5 years | 115 (56%) |

| 6–10 years | 29 (14%) | |

| >10 years | 62 (30%) | |

| Completed influenza immunization | OBGYNs (n = 98) | 65 (66.3%) |

| FPs (n = 108) | 90 (83.3%) | |

| Average number of daily pregnancy consultations | 12 | Translated into 2472 daily pregnancy consultations among our study population. |

| Questions | Responses | All | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Section | |||

| Seasonal influenza disease is an acute respiratory infection caused by the influenza virus, which circulates throughout the world? | True False I do not know | 199 5 2 | (96.6) (2.4) (1) |

| There are 4 types of seasonal influenza viruses, A, B, C, and D. But only type A and B viruses are responsible for seasonal outbreaks and epidemics of the disease. | True False I do not know | 151 31 24 | (73.3) (15) (11.7) |

| The clinical picture of Influenza disease is like the common flu, is rarely severe, and does not cause any death. | True False I do not know | 164 42 0 | (79.6 (20.4) (0) |

| All age groups can be affected by seasonal influenza. However, there are higher risk groups that develop the disease and its complications. Such are: Children under 5 years of age, pregnant women, older adults, individuals with chronic diseases. | True False I do not know | 204 1 1 | (99) (0.5) (0.5) |

| The onset of seasonal influenza symptoms may occur suddenly or progress more slowly, and patients who received the vaccine may have milder symptoms. | True False I do not know | 185 13 8 | (89.8) (6.3) (3.9) |

| The standard criterion for confirming influenza virus infection remains a polymerase chain reaction with reverse transcription (PCR) or viral culture of nasopharyngeal or throat secretions. | True False I do not know | 178 15 13 | (86.4) (7.3) (6.3) |

| Antiviral medications for seasonal influenza include oseltamivir, zanamivir, and baloxavir marboxil. | True False I do not know | 150 37 19 | (72.8) (18) (9.2) |

| The most effective way to prevent infection and disease is through annual vaccination against the Influenza virus of all individuals at risk. | True False I do not know | 197 9 0 | (95.6) (4.4) (0) |

| Pregnant women tend to be frequently hospitalized due to the development of more severe illness and development of complications, and they can even die due to seasonal influenza, than women who are not pregnant. | True False I do not know | 152 35 19 | (73.8) (17) (9.2) |

| Some of the adverse effects of influenza infection in the fetus are the restriction of fetal growth, fetal distress, neural tube defects, preterm birth, increased fetal mortality. | True False I do not know | 100 55 51 | (48.5) (26.7) (24.8) |

| When is the best time to vaccinate pregnant women against seasonal influenza? | Any Trimester 1st 2nd 3rd | 117 49 27 13 | (56.8) (23.8) (13.1) (6.3) |

| Beliefs Section | |||

| Pregnancy per se is NOT a risk factor for developing influenza disease and its complications. | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 47 34 18 43 64 | (22.8) (16.5) (8.7) (20.9) (31.1) |

| Influenza disease does NOT confer any health or developmental risk to the fetus. | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 14 17 15 82 78 | (6.8) (8.3) (7.3) (39.8) (37.9) |

| The influenza vaccine is NOT safe and can cause influenza infection. | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 1 1 11 63 130 | (0.5) (0.5) (5.3) (30.6) (63.1) |

| I have never treated a pregnant patient with influenza, so doubt the severity of this disease in this population. | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 16 27 27 55 81 | (7.8) (13.1) (13.1) (26.7) (39.3) |

| Do you consider that vaccination against the influenza virus in pregnant women is a SAFE and EFFECTIVE practice to prevent the disease? | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 155 43 5 2 1 | (75.2) (20.9) (2.4) (1.0) (0.5) |

| Only pregnant women with chronic degenerative diseases (DM, HBP, Lupus, etcetera.) are prone to contracting Influenza disease and its complications. | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 22 19 4 66 95 | (10.7) (9.2) (1.9) (32) (46.1) |

| Influenza vaccination in pregnant women only gives protection to the mother, but not to the baby. | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 22 19 4 66 95 | (10.7) (9.2) (1.9) (32) (46.1) |

| Pregnant women who were vaccinated against influenza reduce their risk of being hospitalized due to complications. | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 133 58 4 7 4 | (64.6) (28.2) (1.9) (3.4) (1.9) |

| The Influenza vaccine can be applied in pregnant women during any trimester of pregnancy. | Strongly Agree Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly disagree | 113 43 13 25 12 | (54.9) (20.9) (6.3) (12.1) (5.8) |

| Practices Section | |||

| Do you recommend and promote influenza vaccination during pregnancy? | Yes No | 202 4 | (98.1) (1.9) |

| Do you offer influenza vaccination among all your patients regardless of their pregnancy status (pregnant or not pregnant)? | Yes No | 177 29 | (85.9) (14.1) |

| Usually during which pregnancy trimester do you promote or apply influenza vaccination? | 1st 2nd 3rd | 91 93 22 | (44.2) (45.1) (10.7) |

| Do you check the immunization status of all your patients? | Always Very often Sometimes Rarely Never | 117 47 26 5 11 | (56.8) (22.8) (12.6) (2.4) (5.3) |

| Would you be interested in learning more about the benefits of influenza vaccination during pregnancy? | Yes No | 198 8 | (96.1) (3.9) |

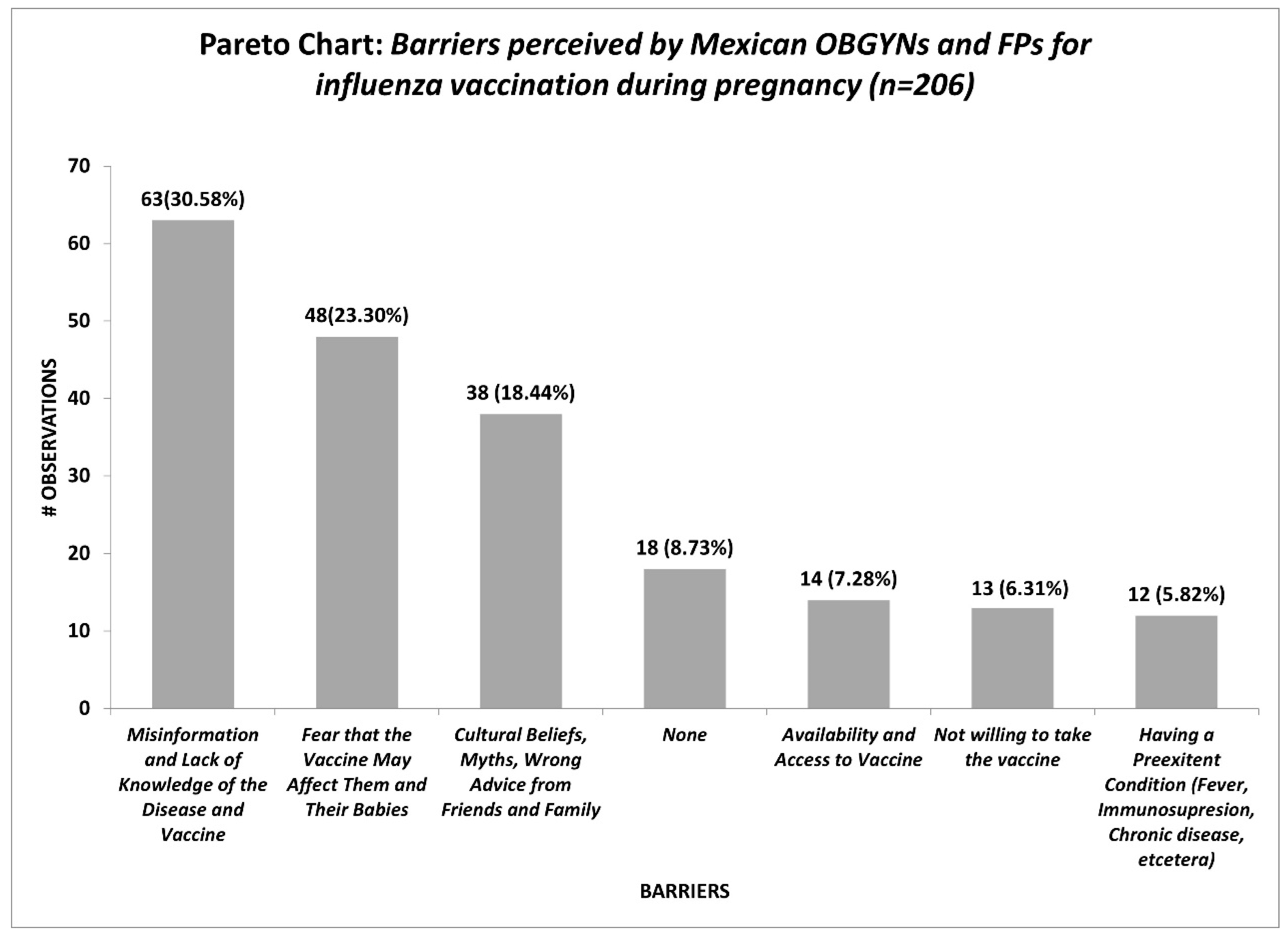

| What challenges or barriers do you consider play a role in influenza vaccine uptake during pregnancy? | Open question | ||

| Odds Ratio Analysis of Provider Vaccination Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OBGYNs | FPs | Female | Male | |||

| YES | 65 | 90 | YES | 100 | 55 | |

| NO | 33 | 18 | NO | 31 | 20 | |

| (OR = 1.25, 95% CI = (0.82–1.91), p-value = 0.28) | (OR = 0.96, 95% CI (0.62–1.48), p-value = 0.85) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lopatynsky-Reyes, E.Z.; Chacon-Cruz, E.; Greenberg, M.; Clemens, R.; Costa Clemens, S.A. Influenza Vaccination during Pregnancy: A Descriptive Study of the Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices of Mexican Gynecologists and Family Physicians. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081383

Lopatynsky-Reyes EZ, Chacon-Cruz E, Greenberg M, Clemens R, Costa Clemens SA. Influenza Vaccination during Pregnancy: A Descriptive Study of the Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices of Mexican Gynecologists and Family Physicians. Vaccines. 2023; 11(8):1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081383

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopatynsky-Reyes, Erika Zoe, Enrique Chacon-Cruz, Michael Greenberg, Ralf Clemens, and Sue Ann Costa Clemens. 2023. "Influenza Vaccination during Pregnancy: A Descriptive Study of the Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices of Mexican Gynecologists and Family Physicians" Vaccines 11, no. 8: 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081383

APA StyleLopatynsky-Reyes, E. Z., Chacon-Cruz, E., Greenberg, M., Clemens, R., & Costa Clemens, S. A. (2023). Influenza Vaccination during Pregnancy: A Descriptive Study of the Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices of Mexican Gynecologists and Family Physicians. Vaccines, 11(8), 1383. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081383