Creating and Activating an Implementation Community to Drive HPV Vaccine Uptake in Texas: The Role of an NCI-Designated Cancer Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose and Significance

1.2. Problem Statement

1.3. Rationale for Resource Activation

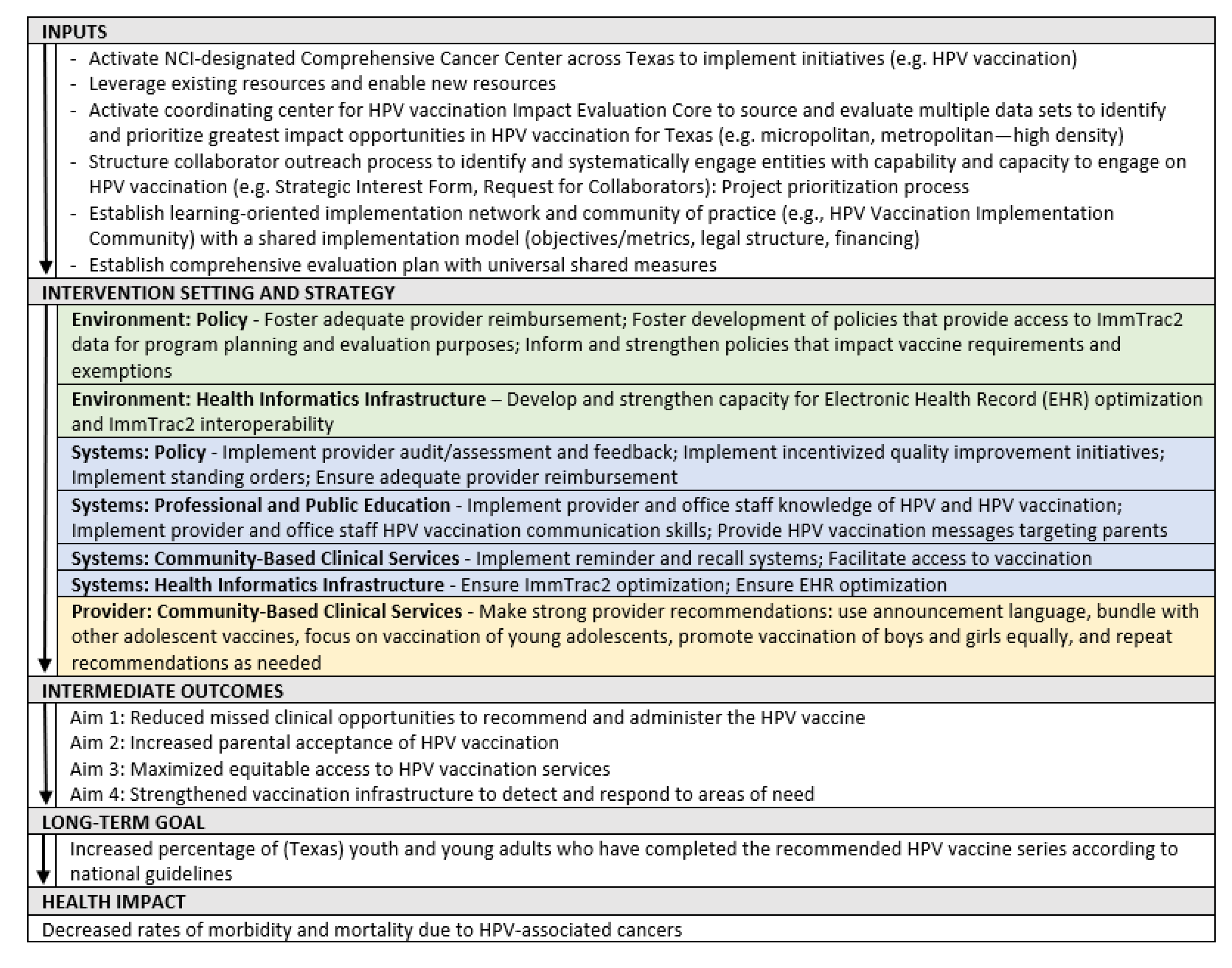

2. Materials and Methods

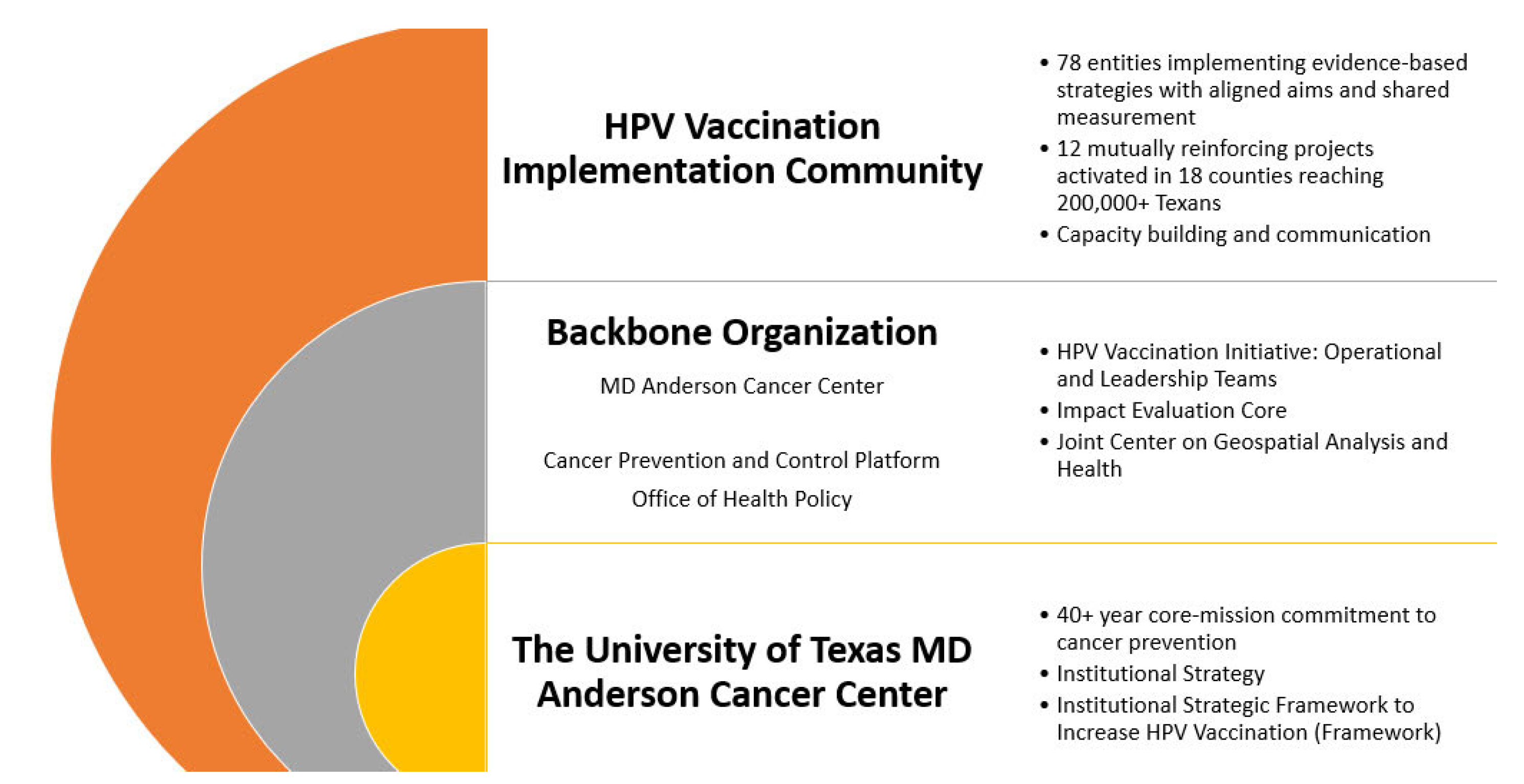

Establishing an Institution-Wide Effort

- Phase I: Assess and Monitor

- Phase II: Plan and Prioritize

- Phase III: Refine and Share

- Aim 1: Reduce missed clinical opportunities to recommend and administer the HPV vaccine

- Aim 2: Increase parental acceptance of HPV vaccination

- Aim 3: Maximize equitable access to HPV vaccination services

- Aim 4: Strengthen the vaccination infrastructure to detect and respond to areas of need

- Phase IV: Implement and Evaluate

- a.

- Development of a governance structure to guide the initiative. In September 2020, a four-pronged governance structure was implemented consisting of four groups: an HPV Vaccination Leadership Team, an HPV Vaccination Operational Team, an HPV Vaccination Alignment Committee, and the HPV Vaccination Implementation Community (Figure 4). The Operational Team is responsible for planning, implementation, alignment of partners/projects, and evaluation. This team meets multiple times weekly to establish and work toward achieving key milestones. The Leadership Team provides oversight through monthly meetings and small-group meetings for specific topic consensus. The HPV Vaccination Alignment Committee consists of internal experts and external reviewers/advisors.

- b.

- Development of the co-implementation model. The MD Anderson HPV Vaccination Initiative adapted an existing co-implementation model created by the Cancer Prevention and Control Platform—Be Well Communities™ [41], which is MD Anderson’s place-based strategy for comprehensive cancer prevention and control and partnership model for community and social impact at the neighborhood level. The converted model incorporates multiple steps that engage potential collaborating organizations to ensure the collective project portfolio supports a robust and comprehensive operational plan that incorporates multiple evidence-based interventions that target regions with low vaccination rates. Based on Be Well Communities™, the Operational Team developed a Request for Collaborators (RFC) process that allowed MD Anderson, in its role as a backbone organization [42], to design shared implementation projects and activate resources to support collaborations.

- c.

- Deployment of the co-implementation model. To implement the RFC, the Operational Team, beginning in October 2020, engaged external entities who informally advised on the development of the Framework. This resulted in a series of dialogues to discern readiness for Framework implementation and to gauge interest in formal collaborations between a range of partners across the state of Texas and MD Anderson. This targeted outreach and engagement with sharing of project portfolios, partners, and proposed plans resulted in deepening ties between organizations as well as identifying new potential collaborators. The focus on stakeholder participation enabled the Operational Team to begin formal engagement as Steward, per the logic model, to activate the novel creation of a portfolio-based implementation community. The following process is being used to develop projects in the portfolio.

- d.

- Creation of an External Review Panel and novel integration of scoring rubrics. The MD Anderson HPV Leadership and Operational Teams invite experts in relevant fields to serve on the External Review Panel to review and score proposals received in response to the RFC. These vetted panelists, based both in Texas and throughout the United States, represent expertise in a field activity associated with increasing HPV vaccination rates: execution of clinical quality-improvement initiatives; delivery of pediatric clinical services; implementation of multi-level public health interventions; and design and implementation of public health and/or health services research.

- e.

- Evaluation of the HPV Vaccination Implementation Community. MD Anderson, in collaboration with its Impact Evaluation Core [51] and RTI International [52], developed a comprehensive mixed-methods evaluation plan to ensure adequate data collection and to align organizational objectives with outcomes. Established in 2019, MD Anderson’s Impact Evaluation Core aims to assess the impact of implementing cancer control initiatives in communities and with priority populations experiencing health disparities, operating on the premise that the key purpose of health program evaluation is to improve prevention, research, public health, and clinical practice. Evaluation activities occur at five levels: program impact, collective impact, shared measurement, cost-effectiveness, and community impact.

- Program impact. Program impact is an assessment of the implementation of the evidence-based interventions (EBIs). Quantitative and qualitative data on program implementation are collected from collaborating organizations via quarterly and annual reports. Each organization completes objectives and metrics tables indicating the implementation status of each EBI. These reports include procedural challenges, successes, updated metrics, and recommendations for sustainability as well as shared measures. MD Anderson reports frequencies for categorical data (e.g., the number of collaborating organizations meeting an objective) and calculates percentages as appropriate (e.g., the percentage of programs demonstrating significant change in a specific health-related outcome). Given the differences in timing of measurement and measures available to evaluate how the initiative has affected health-related outcomes among program participants, analysis is conducted to examine changes at the individual or group (e.g., class, school) level, as appropriate. For qualitative data (e.g., open-ended stakeholder survey items, stakeholder interviews), MD Anderson and RTI code for themes and interweaves data into the report to describe activities, barriers, and facilitators, and to explain trends and contextualize implementation of the programs as intended.

- Collective impact. Collective impact [53] assesses seven distinct areas that focus on the extent to which program activities were implemented as intended and improved health outcomes, as well as the collaborative impact of the initiative. The seven domains are:

- a.

- Implementation of Planned Program Activities/Modification of Plans

- b.

- Health Outcomes at Collaborating Partners and Community Levels

- c.

- Systems Changes at Initiative and Partner Levels

- d.

- Impact within the Community of Practice

- e.

- Lessons Learned

- f.

- Sustainability

- g.

- Cost-effectiveness

- Shared measurement. MD Anderson’s Impact Evaluation Core and RTI facilitated a discussion and sought input from collaborators to establish a set of shared measures. These measures are intended to assess the overall progress of the collaborations’ efforts. The process of developing and utilizing these common sets of measures allows the implementation community to evaluate performance and track progress toward goals. It also helps the implementation community remain aligned and accountable for intended impacts. The HPV Vaccination Implementation Community agreed upon four shared measures: (1) Rate of initiation of HPV vaccination series; (2) Completion/Up to Date HPV vaccination series; (3) Provider knowledge of HPV recommendation best practices, and (4) Provider self-efficacy for communicating with parents. Other measures that collaborators are collecting relate to electronic health records; missed clinical opportunities; and rates stratified by age, race, ethnicity, and gender; among others.

- Cost-effectiveness. As part of MD Anderson’s HPV Vaccination Initiative, RTI is conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis of each of the funded programs. Cost-effectiveness analysis compares the relative costs of achieving the same outcome by means of different activities or interventions. The analysis will be beneficial to both MD Anderson and to each of the participating organizations to help evaluate the operational sustainability of each program. Results will also inform other organizations that may want to implement similar programs. Furthermore, cost-effectiveness evaluation can assist decision-makers in allocating resources to maximize the net public health benefit when choosing among options and EBIs.

- Community impact. The intent is to assess the impact of participation in the HPV Vaccination Implementation Community for a collaborating organization. This includes network mapping to identify the type of engagement the organizations have with each other and whether these developed as a result of their participation. The number of grant or philanthropic proposals submitted and/or awarded that leverage the results of participation in the HPV Vaccination Implementation Community will be collected, among other community impact metrics.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frazer, I.H. Eradicating HPV-Associated Cancer Through Immunization: A Glass Half Full. Viral Immunol. 2018, 31, 8–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meites, E.; Kempe, A.; Markowitz, L.E. Use of a 2-Dose Schedule for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination—Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 1405–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingali, C.; Yankey, D.; Elam-Evans, L.D.; Markowitz, L.E.; Valier, M.R.; Fredua, B.; Crowe, S.J.; Stokley, S.; Singleton, J.A. National Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccination Coverage among Adolescents (13–17 Years). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/teenvaxview/data-reports/index.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Immunizations. In Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Texas 2036. Shaping Our Future: A Strategic Framework for Texas, 2nd ed. 2022. Available online: https://texas2036.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Texas-2036-2022-Strategic-Framework-Report.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Texas Cancer Registry. Cancer Epidemiology and Surveillance Branch. HPV-Associated Cancers in Texas, 2013–2017; Texas Department of State Health Services: Austin, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The VFC Program: At a Glance. 2016. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/vfc/about/index.html (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- City of San Antonio. Texas Vaccines for Children & Adult Safety Net Program. 2023. Available online: https://www.sanantonio.gov/health/healthservices/immunizations/vaccineforchildren (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Diasio, C. Pediatric Vaccination: Who Bears the Burden? 2016. Available online: https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/pediatric-vaccination-bears-burden# (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map. Available online: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/ (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- United States Census Bureau Home Page. Available online: https://data.census.gov/ (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Medicaid Enrollment (Birth to Age 18) in Texas. 2023. Available online: https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/8528-medicaid-enrollment-birth-to-age-18#detailed/2/any/false/2048,574,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868/any/17213,17214 (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Alker, J.; Osorio, A.; Park, E. Number of Uninsured Children Stabilized and Improved Slightly During the Pandemic. 2022. Available online: https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/ACS-Uninsured-Kids-2022-EMB-1-pm-3.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Supplementary Table 2. Estimated Vaccination Coverage with Selected Vaccines and Doses among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years, by Health Insurance Status—National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen), United States, 2021. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/teenvaxview/pubs-presentations/NIS-teen-vac-coverage-estimates-2021-tables.html (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Victory, M.; Do, T.Q.N.; Kuo, Y.-F.; Rodriguez, A.M. Parental knowledge gaps and barriers for children receiving human papillomavirus vaccine in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 1678–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, C.A.; Borrell, L.N.; Shen, Y.; Kimball, S.; Zimba, R.; Kulkarni, S.; Rane, M.; Rinke, M.L.; Fleary, S.A.; Nash, D. Missed routine pediatric care and vaccinations in US children during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Med. 2022, 158, 107025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, M.; Loux, T.; Shacham, E.; Tiro, J.A.; Arnold, L.D. Barriers to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among young adults, aged 18–35. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 29, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.; Gilbert, P.A.; Ashida, S.; Charlton, M.E.; Scherer, A.; Askelson, N.M. Challenges to Adolescent HPV Vaccination and Implementation of Evidence-Based Interventions to Promote Vaccine Uptake during the COVID-19 Pandemic: “HPV Is Probably Not at the Top of Our List”. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2022, 19, E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, M.; Baler Manwell, L.; Schwartz, M.D.; Williams, E.S.; Bobula, J.A.; Brown, R.L.; Varkey, A.B.; Man, B.; McMurray, J.E.; Maguire, A.; et al. Working Conditions in Primary Care: Physician Reactions and Care Quality. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.; Poplau, S.; Brown, R.; Yale, S.; Grossman, E.; Varkey, A.B.; Williams, E.; Neprash, H.; Linzer, M. Time Pressure During Primary Care Office Visits: A Prospective Evaluation of Data from the Healthy Work Place Study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T. Revitalizing Primary Care, Part 1: Root Causes of Primary Care’s Problems. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, J.G.; Marsh, R.; Anderson-Mellies, A.; Williams, J.L.; Fisher, M.P.; Cockburn, M.G.; Dempsey, A.F.; Cataldi, J.R. Pre-implementation evaluation for an HPV vaccine provider communication intervention among primary care clinics. Vaccine 2022, 40, 4835–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, D.Y.; Rundall, T.G.; Tallia, A.F.; Cohen, D.J.; Halpin, H.A.; Crabtree, B.F. Rethinking Prevention in Primary Care: Applying the Chronic Care Model to Address Health Risk Behaviors. Milbank Q. 2007, 85, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Physicians, Health and Public Policy Committee. Solutions to the Challenges Facing Primary Care Medicine; American College of Physicians: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: https://assets.acponline.org/acp_policy/policies/solutions_challenges_primarycare_2009.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Smith, J.D.; Li, D.H.; Rafferty, M.R. The Implementation Research Logic Model: A method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavundza, E.J.; Iwu-Jaja, C.J.; Wiyeh, A.B.; Gausi, B.; Abdullahi, L.H.; Halle-Ekane, G.; Wiysonge, C.S. A Systematic Review of Interventions to Improve HPV Vaccination Coverage. Vaccines 2021, 9, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niccolai, L.M.; Hansen, C.E. Practice- and Community-Based Interventions to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Coverage: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, L.R.; Wethington, H.R.; Finnie, R.K.C.; Mercer, S.L.; Merlo, C.; Michael, S.; Sliwa, S.; Pratt, C.A.; Ochiai, E. A Community Guide Systematic Review: School Dietary and Physical Activity Interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 64, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, C.M.; Smith, T.; de Moor, J.S.; Glasgow, R.E.; Khoury, M.J.; Hawkins, N.A.; Stein, K.D.; Rechis, R.; Parry, C.; Leach, C.R.; et al. An action plan for translating cancer survivorship research into care. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- President’s Cancer Panel. HPV Vaccination for Cancer Prevention: Progress, Opportunities, and Renewed Call to Action. Available online: https://prescancerpanel.cancer.gov/report/hpvupdate/pdf/PresCancerPanel_HPVUpdate_Nov2018.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- The Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT). 2018 Texas Cancer Plan. Available online: https://www.cprit.texas.gov/media/1457/tcp2018_web_09192018.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- United States Census Bureau. State Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020–2022. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer Moon Shots Program. 2023. Available online: https://www.mdanderson.org/cancermoonshots.html (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Planning Core Team. Institutional Strategic Framework to Increase HPV Vaccination; The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center: Huston, TX, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.texascancer.info/pdfs/mdandersonhpvstratframework.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control & Population Science. Supporting Community Outreach and Engagement; National Cancer Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/research-emphasis/supplement/coe (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- World Health Organization, GRISP Steering Committee. Global Routine Immunization Strategies and Practices (GRISP): A Companion Document to the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204500/9789241510103_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Global Immunization Strategic Framework 2021–2030. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/immunization/docs/global-immunization-framework-508.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Texas Department of Health and Human Services. ImmTrac2 Texas Immunization Registry; DSHS: Huston, TX, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.dshs.texas.gov/immunization-unit/immtrac2-texas-immunization-registry (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Rechis, R.; Oestman, K.B.; Caballero, E.; Brewster, A.; Walsh, M.T.; Basen-Engquist, K.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Tektiridis, J.H.; Moreno, M.; Williams, P.A.; et al. Be Well Communities™: Mobilizing communities to promote wellness and stop cancer before it starts. Cancer Causes Control 2021, 32, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collective Impact Forum. The Value of Backbone Organizations in Collective Impact. 2013. Available online: https://collectiveimpactforum.org/resource/the-value-of-backbone-organizations-in-collective-impact/ (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Ma, G.X.; Zhu, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhai, S.; Lin, T.R.; Zambrano, C.; Siu, P.; Lai, S.; Wang, M.Q. A Multilevel Intervention to Increase HPV Vaccination among Asian American Adolescents. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Do, T.Q.N.; Hsu, E.; Schmeler, K.M.; Montealegre, J.R.; Rodriguez, A.M. School-based human papillomavirus vaccination program for increasing vaccine uptake in an underserved area in Texas. Papillomavirus Res. 2019, 8, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, K.; Frawley, A.; Garland, E. HPV vaccination: Population approaches for improving rates. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 1589–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yared, N.; Malone, M.; Welo, E.; Mohammed, I.; Groene, E.; Flory, M.; Basta, N.E.; Horvath, K.J.; Kulasingam, S. Challenges related to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake in Minnesota: Clinician and stakeholder perspectives. Cancer Causes Control 2021, 32, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, T.; Hooper, G.L. A School-Based Intervention to Increase HPV Vaccination Rates. J. Dr. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 12, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shah, M.D.; Glenn, B.A.; Chang, L.C.; Chung, P.J.; Valderrama, R.; Uyeda, K.; Szilagyi, P.G. Reducing Missed Opportunities for Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in School-Based Health Centers: Impact of an Intervention. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abt Associates. Learning and Evaluation Final Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.macfound.org/media/files/final_100andchange_learning_and_evaluation_report.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Glasgow, R.E.; Harden, S.M.; Gaglio, B.; Rabin, B.; Smith, M.L.; Porter, G.C.; Ory, M.G.; Estabrooks, P.A. RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice with a 20-Year Review. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The Impact Evaluation Core. 2023. Available online: https://www.mdanderson.org/research/research-resources/core-facilities/impact-evaluation-core.html (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- RTI International. Available online: https://www.rti.org/ (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Kania, J.; Kramer, M. Collective Impact. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2011, 9, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination for Prevention of HPV-Related Cancers. 2022. Available online: https://www.mdanderson.org/content/dam/mdanderson/documents/for-physicians/algorithms/screening/risk-reduction-hpv-vaccination-web-algorithm.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2023).

| Implementation Setting | FQHC System 1 | FQHC System 2 | Health System 1 | FQHC System 3 | Academic Medical Center 1 | Academic Medical Center 2 | Academic Medical Center 3 | Academic Medical Center 4 | Academic Institution | Academic Medical Center 5 | Academic Dental Center 1 | Academic Medical Center 6 | Totals for Settings and EBS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | 6 | ||||||

| FQHC System | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | 6 | ||||||

| Independent School District | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | 5 | |||||||

| Dental Clinic | ⌧ | ⌧ | ⌧ | 3 | |||||||||

| Health System | ⌧ | ⌧ | 2 | ||||||||||

| Evidence-Based Interventions (EBIs) | |||||||||||||

| Implement provider & office staff HPV vaccination communications skills | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 12 |

| Implement provider and office staff knowledge of HPV and HPV vaccination | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 12 |

| Provide HPV vaccination messages targeting parents | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 11 | |

| Facilitate access to vaccination | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 11 | |

| Implement reminder and recall systems | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 10 | ||

| Promote vaccination of boys and girls equally | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 10 | ||

| Make strong provider recommendations | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 9 | |||

| Bundle with other adolescent vaccines | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 9 | |||

| Focus on vaccination of young adolescents | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 9 | |||

| Repeat recommendations as needed | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 7 | |||||

| Implement provider audit/assessment and feedback | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 7 | |||||

| Ensure electronic health record optimization | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 6 | ||||||

| Use announcement language | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ | 6 | ||||||

| Implement standing orders | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | 5 | |||||||

| Ensure ImmTrac2 optimization | ● | ● | ● | ● | 4 | ||||||||

| Implement incentivized quality-improvement initiatives | ● | ● | 2 | ||||||||||

| Total Interventions by Org | 16 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 130 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bello, R.S.; Walsh, M.T., Jr.; Harper, B.; Amos, C.E., Jr.; Oestman, K.; Nutt, S.; Galindez, M.; Block, K.; Rechis, R.; Bednar, E.M.; et al. Creating and Activating an Implementation Community to Drive HPV Vaccine Uptake in Texas: The Role of an NCI-Designated Cancer Center. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11061128

Bello RS, Walsh MT Jr., Harper B, Amos CE Jr., Oestman K, Nutt S, Galindez M, Block K, Rechis R, Bednar EM, et al. Creating and Activating an Implementation Community to Drive HPV Vaccine Uptake in Texas: The Role of an NCI-Designated Cancer Center. Vaccines. 2023; 11(6):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11061128

Chicago/Turabian StyleBello, Rosalind S., Michael T. Walsh, Jr., Blake Harper, Charles E. Amos, Jr., Katherine Oestman, Stephanie Nutt, Marcita Galindez, Kaitlyn Block, Ruth Rechis, Erica M. Bednar, and et al. 2023. "Creating and Activating an Implementation Community to Drive HPV Vaccine Uptake in Texas: The Role of an NCI-Designated Cancer Center" Vaccines 11, no. 6: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11061128

APA StyleBello, R. S., Walsh, M. T., Jr., Harper, B., Amos, C. E., Jr., Oestman, K., Nutt, S., Galindez, M., Block, K., Rechis, R., Bednar, E. M., Tektiridis, J., Foxhall, L., Moreno, M., Shete, S., & Hawk, E. (2023). Creating and Activating an Implementation Community to Drive HPV Vaccine Uptake in Texas: The Role of an NCI-Designated Cancer Center. Vaccines, 11(6), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11061128