Factors Influencing Parental and Individual COVID-19 Vaccine Decision Making in a Pediatric Network

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants, and Setting

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

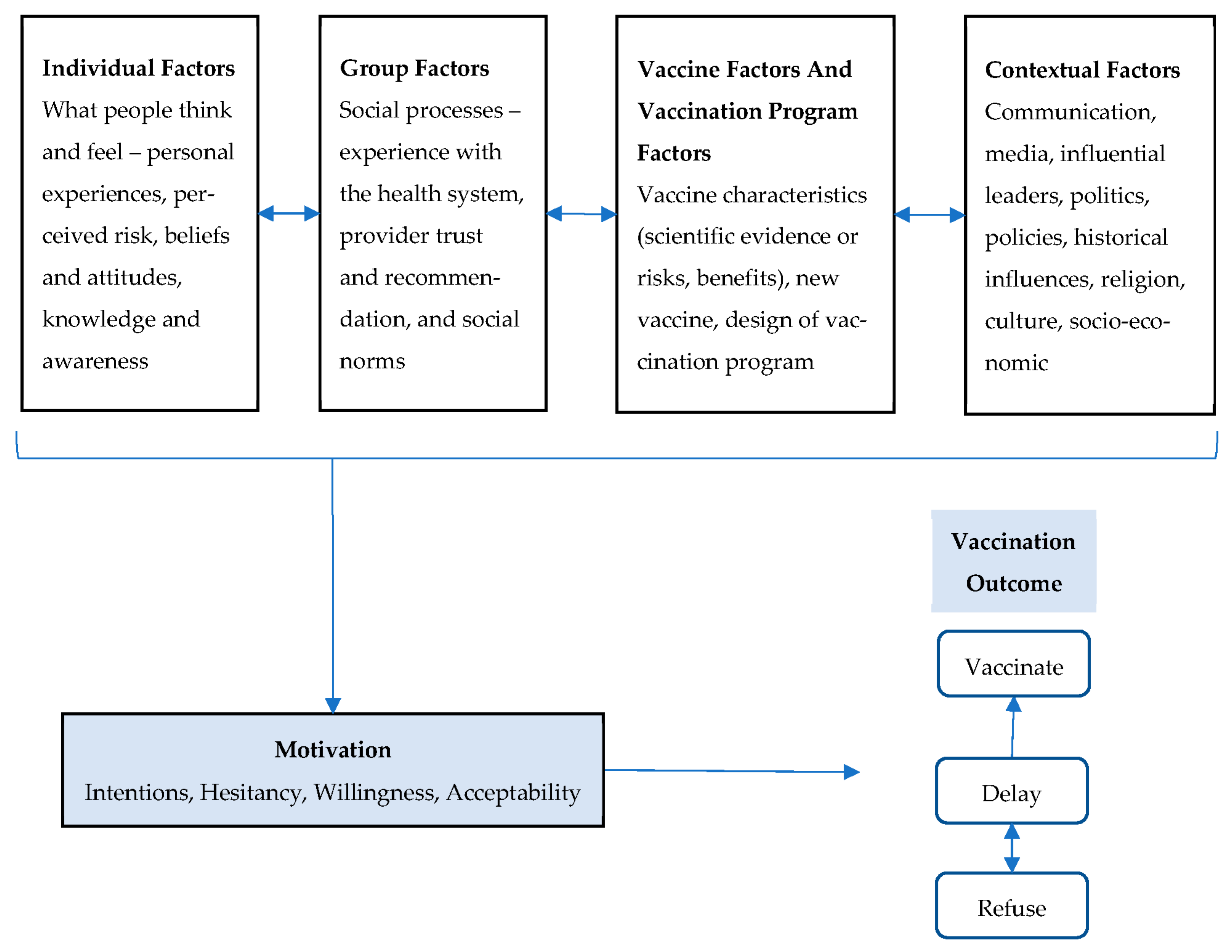

3.1. Individual Factors

3.1.1. Personal Medical History and Experience with Previous Disease

3.1.2. Beliefs (Autism, Altruism, and Conspiracy)

3.1.3. Knowledge to Make Decisions Is Informed by Trusted Sources

3.1.4. Risk Perception of Disease as Burden Shifts

3.2. Group Factors

3.2.1. Provider Trust and Experience with Health System

3.2.2. Vaccination as a Norm and Social Norm

3.3. Vaccine and Vaccination Program Factors

3.3.1. Scientific Evidence of Risk and Benefit: Long-Term Safety and Efficacy

3.3.2. “Newness” of the Vaccine

3.3.3. Vaccination Program Design and Supply

3.4. Contextual Factors

3.4.1. Communication and Media

3.4.2. Politics and Policies

3.4.3. Historic Influences, Religion, Color, Gender, and Socio-Economic Status

3.5. Guidance for Other Parents and Recommendations to Policymakers

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orenstein, W.A.; Gellin, B.G.; Beigi, R.H.; Despres, S.; Lynfield, R.; Maldonado, Y.; Mouton, C.; Rawlins, W.; Rothholz, M.C.; Smith, N.; et al. Assessing the State of Vaccine Confidence in the United States: Recommendations from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee: Approved by the National Vaccine Advisory Committee on June 10, 2015. Public Health Rep. 2015, 130, 573. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine Hesitancy: An Overview. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomoni, M.G.; di Valerio, Z.; Gabrielli, E.; Montalti, M.; Tedesco, D.; Guaraldi, F.; Gori, D. Hesitant or Not Hesitant? A Systematic Review on Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Different Populations. Vaccine 2021, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, H.J.; Cooper, L.Z.; Eskola, J.; Katz, S.L.; Ratzan, S. Addressing the Vaccine Confidence Gap. Lancet 2011, 378, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, A.; Saville, A.W.; Albertin, C.; Zimet, G.; Breck, A.; Helmkamp, L.; Vangala, S.; Dickinson, L.M.; Rand, C.; Humiston, S.; et al. Parental Hesitancy About Routine Childhood and Influenza Vaccinations: A National Survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20193852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szilagyi, P.G.; Albertin, C.S.; Gurfinkel, D.; Saville, A.W.; Vangala, S.; Rice, J.D.; Helmkamp, L.; Zimet, G.D.; Valderrama, R.; Breck, A.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of HPV Vaccine Hesitancy among Parents of Adolescents across the US. Vaccine 2020, 38, 6027–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Clarke, R.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Walker, J.L.; Paterson, P. Parents’ and Guardians’ Views on the Acceptability of a Future COVID-19 Vaccine: A Multi-Methods Study in England. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.C.; Fang, Y.; Cao, H.; Chen, H.; Hu, T.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z. Parental Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination for Children Under the Age of 18 Years: Cross-Sectional Online Survey. JMIR Pediatr Parent 2020, 3, e24827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Children and COVID-19: State-Level Data Report. Available online: https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/children-and-covid-19-state-level-data-report/ (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 Disparities|KFF. Available online: https://www.kff.org/statedata/collection/covid-19-disparities/ (accessed on 13 February 2022).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration FDA Authorizes Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine for Emergency Use in Children 5 through 11 Years of Age|FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-emergency-use-children-5-through-11-years-age (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Postpones Advisory Committee Meeting to Discuss Request for Authorization of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine for Children 6 Months Through 4 Years of Age|FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-postpones-advisory-committee-meeting-discuss-request-authorization (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration COVID-19 Vaccines|FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/emergency-preparedness-and-response/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Brewer, N.T. What Works to Increase Vaccination Uptake. Acad. Pediatrics 2021, 21, S9–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Chapman, G.B.; Rothman, A.J.; Leask, J.; Kempe, A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science Into Action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2018, 18, 149–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Helmkamp, L.J.; Szilagyi, P.G.; Zimet, G.; Saville, A.W.; Gurfinkel, D.; Albertin, C.; Breck, A.; Vangala, S.; Kempe, A. A Validated Modification of the Vaccine Hesitancy Scale for Childhood, Influenza and HPV Vaccines. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1831–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Committee for Quality Assurance Immunizations for Adolescents—NCQA. Available online: https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/immunizations-for-adolescents/ (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Carson, S.L.; Casillas, A.; Castellon-Lopez, Y.; Mansfield, L.N.; Morris, D.; Barron, J.; Ntekume, E.; Landovitz, R.; Vassar, S.D.; Norris, K.C.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Decision-Making Factors in Racial and Ethnic Minority Communities in Los Angeles, California. JAMA Network Open 2021, 4, e2127582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser Family Foundation KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor Dashboard|KFF. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/dashboard/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-dashboard/ (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Center’s for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Vaccine Confidence Survey Question Bank; Center’s for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research: A Synthesis of Recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014.

- Kiviniemi, M.T.; Orom, H.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A. Prevention Is Political: Political Party Affiliation Predicts Perceived Risk and Prevention Behaviors for COVID-19. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, N.M.; Laydon, D.; Nedjati-Gilani, G.; Imai, N.; Ainslie, K.; Baguelin, M.; Bhatia, S.; Boonyasiri, A.; Cucunubá, Z.; Cuomo-Dannenburg, G.; et al. Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to Reduce COVID-19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, D.G.; Rhodes, H.; Bandealy, A. Pandemic Recovery for Children—Beyond Reopening Schools. JAMA Pediatrics 2022, 176, 347–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuter, B.J.; Browne, S.; Momplaisir, F.M.; Feemster, K.A.; Shen, A.K.; Green-McKenzie, J.; Faig, W.; Offit, P.A. Perspectives on the Receipt of a COVID-19 Vaccine: A Survey of Employees in Two Large Hospitals in Philadelphia. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Make, J.; Lauver, A. Increasing Trust and Vaccine Uptake: Offering Invitational Rhetoric as an Alternative to Persuasion in Pediatric Visits with Vaccine-Hesitant Parents (VHPs). Vaccine X 2022, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, M.J. Public Misunderstanding of Science? Reframing the Problem of Vaccine Hesitancy. Perspect. Sci. 2016, 24, 552–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossen, I.; Hurlstone, M.J.; Lawrence, C. Going with the Grain of Cognition: Applying Insights from Psychology to Build Support for Childhood Vaccination. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weaver, J.L.; Swank, J.M. Parents’ Lived Experiences With the COVID-19 Pandemic: Fam. J. 2020, 29, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranji, U.; Frederiksen, B.; Salganicoff, A.; Hamel, L.; Lopes, L. Role of Mothers in Assuring Children Receive COVID-19 Vaccinations|KFF. Available online: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/role-of-mothers-in-assuring-children-receive-covid-19-vaccinations/ (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- Ek, S. Gender Differences in Health Information Behaviour: A Finnish Population-Based Survey. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Ice breaker.

|

| Characteristic | Non-Hesitant (N = 25) | Hesitant (N = 16) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years [IQR] | 40 [35–45] | 46.5 [42–49] | 0.004 * | ||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Sex, assigned at birth | 0.512 | ||||

| Female | 23 | 92% | 16 | 100% | |

| Male | 2 | 8% | - | - | |

| Gender | 0.700 | ||||

| Woman | 22 | 88% | 16 | 100% | |

| Man | 2 | 8% | - | - | |

| Non-binary | 1 | 4% | - | - | |

| Sexual orientation | 0.266 | ||||

| Heterosexual or straight | 19 | 76% | 15 | 94% | |

| Gay or lesbian | - | - | 1 | 6% | |

| Bisexual | 3 | 12% | - | - | |

| Queer | 1 | 4% | - | - | |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 8% | - | - | |

| Hispanic, Latino/a/x, or Spanish origin | |||||

| Yes | 1 | 4% | - | - | - |

| No | 24 | 96% | 16 | 100% | |

| Race | |||||

| White or Caucasian | 20 | 80% | 5 | 31.3% | 0.006 * |

| Black or African-American | 3 | 12% | 9 | 56.3% | 0.014 * |

| Asian | 1 | 4% | 1 | 6.3% | |

| Multiple | 1 | 4% | 1 | 6.3% | |

| Household income | 0.085 | ||||

| Less than USD 25,000/year | 1 | 4% | 2 | 12.5% | |

| USD 25,000–49,999/year | 2 | 8% | 3 | 18.8% | |

| USD 50,000–74,999/year | 1 | 4% | 3 | 18.8% | |

| USD 75,000–99,999/year | 4 | 16% | 2 | 12.5% | |

| USD 100,000–149,999/year | 4 | 16% | 4 | 25.0% | |

| Over USD 150,000/year | 13 | 52% | 2 | 12.5% | |

| Highest degree | 0.048 * | ||||

| Regular high school diploma | - | - | 2 | 12.5% | |

| GED or alternative credential | - | - | 1 | 6.3% | |

| Some college credit | 2 | 8% | 6 | 37.5% | |

| Associate’s degree (i.e., AA, AS) | 2 | 8% | - | - | |

| Bachelor’s degree (i.e., BA, BS) | 5 | 20% | 3 | 18.8% | |

| Master’s degree (i.e., MA, MS, MSW, MBA) | 10 | 40% | 2 | 12.5% | |

| Professional degree (i.e., MD, DOS, JD) | 3 | 12% | 1 | 6.3% | |

| Doctorate degree (i.e., PhD, EdD) | 3 | 12% | 1 | 6.3% | |

| Number of children | 0.187 | ||||

| 1 | 12 | 48% | 4 | 25% | |

| 2 | 9 | 36% | 4 | 25% | |

| 3 | 3 | 12% | 5 | 31.3% | |

| 4 | 1 | 4% | 2 | 12.5% | |

| 6 | - | - | 1 | 6.3% | |

| COVID-19 vaccination status, parent | |||||

| Yes, fully vaccinated | 24 | 96% | 14 | 87.5% | 0.550 |

| No | 1 | 4% | 2 | 12.5% | |

| Influenza vaccination status, parent | 0.554 | ||||

| Yes | 20 | 80% | 11 | 68.8% | |

| No, but I intend to | - | - | 1 | 6.3% | |

| No | 5 | 20% | 4 | 25% | |

| Influenza vaccination status, first child | 0.043 * | ||||

| Yes | 19 | 76% | 7 | 43.8% | |

| No, but I intend to | - | - | 2 | 4.9% | |

| No | 6 | 24% | 7 | 43.8% | |

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Individual Factors | |

| Personal medical history and experience with previous disease | “So I want her [daughter] vaccinated ASAP. She has asthma, She had RSV over the summer. I’ve already seen her on oxygen before.” (FG 1: non-hesitant) |

| “My grandmother had polio in 1952 she got it and she was in an iron lung for about nine months…. My parents noted like this is why we get the vaccinations because look what happened to grandma.” (FG 2: non-hesitant) | |

| “I also lost friends to COVID early on and colleagues and it was honestly home-grown videos that people were post-ing that really got me there and recognize that if I were to get it and I passed away, what that would do and look like for my family and for my kids.” (FG 4: non-hesitant) | |

| “When the kids were younger, we were really good about getting the flu shot and then we knew the strains could be different. And my daughter got the flu anyway, and I think we got lax after that.” (FG 7: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Beliefs (altruism, conspiracy, autism) | “My son has autism and intellectual disability. I have questioned whether or not I should have got him vaccinated, when he got vaccinated. I had some concern after he developed his disabilities about the amount of vaccinations that he was receiving at one time. However, despite those beliefs that I had, I still chose to get him vaccinated against COVID.” (FG5: non-hesitant) |

| “I just felt like the whole COVID situation itself, like I said, was just like a conspiracy to de-population. So I don’t re-ally trust anything that has to like deal with it for real for real.” (FG 6: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Knowledge (facts) to make decisions is informed by trusted sources | “When a Lyme disease vaccine became available for people, I was one of the first, I was so excited. I went out, I did it. And then as time happened, it stopped being a recommended thing. So that’s why I don’t do a blanket. I will do it. Sometimes the science catches up. But to the best of my ability and with the information that’s available at the time I have to make a decision, I will make that decision. I’m just not going to blanket say whatever it is that’s recommended I will do.” (FG 1: non-hesitant) |

| “…the part that is difficult to me as a parent, to be honest is even though I was feeling like 99% good about it, I always feel like it’s hard to choose something for your child’s body. Like it’s easy to choose for yourself.” (FG 2: non-hesitant) | |

| “As far as in a COVID shot or whatever, I just feel like, give me a couple of more years and see what had happened. Like, I felt like it was something that was made too fast. It’s not too many studies, you know, it’s only been a couple of years into it. Somewhere down the line it might be an underlining situation. Underlying situation, meaning something will come up that we didn’t know before.” (FG 6: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “I think my doctor’s office told me they had never seen any kind of adverse effects in their practice. It’s a lot. You know, as a large [medical] group it just kinda helped. They gave me a little bit of a history of the vaccine [and] talking to my kids the doctors did with me present about what are they risking by not getting the vaccine at that point [helped]” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Risk perception of disease as burden shifts | “I’m super cautious because I’ve seen what it could do the extreme of deaths or whatever. I’ve seen personally, what it can do and it’s not something that somebody I feel should be laxed about.” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) |

| “I thought that given the rates of serious illness and all of the deaths that were happening in a very short period of time, I thought it made sense, in my opinion, or on the side of caution and go with [vaccination.]” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Group Factors | |

| Experience with health system and provider trust | “I don’t have much of a medical background…I don’t really understand how my lights work in my house, but I still use them” (FG 3: non-hesitant) |

| “I’m a firm believer in partnering with my pediatrician. I place a lot of trust in them and believe that they’re going to make the right decisions. They’re the experts here.” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “Oh, the vaccine itself and the way, how the government just put everything out…you know, that was the only concern that I really have. Like if someone’s vaccinated, I’m not like scared to be around them or anything like that. You know, I know nothing could come from it. It’s just there. I don’t know what they’re offering to put into our bodies” (FG 6: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “I definitely don’t trust social media with anything. And, with news not being so on the up and up lately, I just don’t trust it anymore either. So I’m only going to trust the doctors. You pretty much get the same information from them, whether it’s routine vaccinations or with the COVID.” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Vaccination as a norm and social norms | “They’re [children] doing the best that they can, but their peer group with a lot of unvaccinated people, there’s a social component that I have to be comfortable with in order for their emotional wellbeing and a lot of their, those unvaccinated kids have had COVID. So at this point, they’re as immune as my kids…. We just went to an indoor playground…and I was crawling out of my skin with the people around us, but for my kids’ emotional wellbeing, I’m ready to make that phase back into society.” (FG 1: non-hesitant) |

| “One thing I have used to convince some friends who are vaccine hesitant is I found something on Reddit, the Herman Cane award where people take photos of people on Facebook who were anti vax and got sick with COVID and died and on their death bed were like I wish I got the vaccine…. Because I think if you don’t know anyone who has died with COVID, you are probably less likely to take it seriously. Empathy is probably key to get someone to get vaccinated, so conveying it’s really serious and people are really dying.” (FG 3: non-hesitant) | |

| “My kids definitely get them [routine vaccines]. I do feel as though they [are] very important because I had them and it did no harm to me. You know what I’m saying? It was something that I experienced first in my lifetime, and know that it’s safe for my children. I have no concerns about vaccinating [for the COVID shot]..” (FG 6: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “So high school level, a lot of people interpret that as I don’t have to wear a mask, even if my mom wants me to kind of thing. The policy that was in place was not at all protective and it was a very bullying environment. As, as one of the other moms said, it’s [school policies have] been a bullying environment this whole time making people feel bad for wanting to protect themselves or their families” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “Yeah, well, the problem was it wasn’t like, I knew that a portion of our school population was not vaccinated, but I think for me, the problem was that people were knowingly sending their kids to school with COVID. They were knowingly sending their kids to school symptomatic and they were not masking. So it was like, they were almost guaranteeing the spread of COVID, to a point where it was ridiculous. It wasn’t like a normal. Like it was just, wasn’t normal. It wasn’t like going to the grocery store where everyone’s just masked and like, careful” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “Itt just felt like the right thing to do, honestly. I didn’t really question any of it. You know, you read stories of history of what these horrible diseases have done. And if we have a way to prevent them, it just wasn’t something that, other than Gardasil, that was one that I did kind of put a little extra thought into and give it a little extra time, just because it was fairly new. But for the other stuff [routine vaccination], it wasn’t even a question for me.” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Vaccine And Vaccination Program Factors | |

| Scientific evidence of risk and benefit: long-term safety and efficacy | “…if you decide not to get the mumps vaccine, your kids still probably not going to get mumps because everybody else has already had the mumps vaccine and mumps isn’t going around right now. But COVID-19 is so even if you’re feeling like, oh, I wish I had more time, you know, you don’t have more time.” (FG 2: non-hesitant) |

| “I think for us, it’s a lot of, you know, a lot of concern around what the long-term picture is…”. “I mean, we know a little bit about, like multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children…obviously we only have like a couple of years of data on this, so far, but for us really, it’s just the concern on the long-term effects.” (FG 4: non-hesitant) | |

| “I did get their vaccines, their COVID vaccines, but I did delay them for a few months just to see, you know, what adverse reactions were there. And I feel, you know, the same, I trust science. You know, even though I am still weary, I’m just going to have faith that, you know, it’s going to be a positive thing and we’re going to eliminate this virus and move forward.” (FG 6: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “Newness” of the vaccine | “I think COVID because there’s just so much different information, healthcare routines. I was like, we have kids, this is the schedule, we’re doing the schedule [for routine]. I never really thought twice about it. In fact, I think COVID because it’s quote unquote new, but I know it’s not entirely new” (FG 2: non-hesitant) |

| “I felt like it was important to do it..., I don’t know if I want to be the first in line” (FG 3: non-hesitant) | |

| “I’m pretty comfortable with, I mean like chicken pox and all that have been out, you know, that vaccine has been out forever. I don’t hear anything, you know, bad about it. And as far as reactions and things like that with COVID, I’ve heard many different stories, whether it’s from patients, doctors, personal experiences. So it makes it a little iffy. Is it because they’re different, they’re conflicting information or just hearing about it, like hearing that there are reactions and things” (FG 7: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “I just feel as though it hasn’t been out long enough, I would like more research to be done on it. Especially with my oldest having a heart murmur, they were saying something about it does it can affect heart in some adolescent children. So that is one concern. Other than it not being out long enough, I believe as time goes on, you know, they have to tweak medications and things like that” (FG 7: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “I have two boys and a girl and I was honestly a little more hesitant with my daughter. She was the last one I vaccinated just because I was concerned about reproductive issues and the unknowns” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Vaccination program design and supply | “One thing that I will say is I was actually really disappointed that CHOP didn’t do a better job of reaching out to families to get them appointments… I had friends who had their…pediatricians who gave them appointments to be ready on that day. And CHOP didn’t have any for like two or three weeks. And they also didn’t offer a flu shot together with the COVID shot, which I also thought was a huge missed opportunity” (FG 4: non-hesitant) |

| “So, I mean, if I could get it at the doctor, I would, but I felt so passionate about getting it quickly that I did it at a drive-up site that looked like a military operation in northern New Jersey” (FG 4: non-hesitant) | |

| “The access, maybe they should have more things out there because not everybody is available during normal business hours. So I was thinking maybe something where it could be more of a 24 h thing. You’ve got parents that might work overnight and you can’t get there in the timeframe to that opening” (FG 7: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “In the beginning it was hard to get an appointment. But then, once you got your first appointment, they scheduled you for your second, and then the booster was fine” (FG 7: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “The county made that easy. Actually you could just go, there were no appointments” (FG 7: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Contextual Factors | |

| Communication and media | “I think it’s a very sensitive topic, but when it comes to like, just protecting my friends, you know, adults, I do try to emphasize that there is a tremendous amount of data available around the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines. And that many times what they’re reading on, for example, social media is not, I hate to say this, but it’s, if they’re reading fake news, consider your sources and be sure that you’re not blindly clicking on some headline that when you dig deeper, this actually happened” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) |

| Politics and policies | “Originally for us it [the trusted source] was the CDC, but lately they’ve chosen not to follow the science and bow to political pressure. And so I am less inclined now to look at the CDC… because the politics, the pressure that’s coming from the public is, look, we’re getting ready to go into midterm elections and people are fed up with COVID and we just want to get back to normal and they’re sick of masks… And there really isn’t good reason to explain why they’re changing their position at this point, except for the pushback they are getting” (FG 1: non-hesitant) |

| “I’ve lost a lot of respect for them [CDC], you know, at some point I did work for them. And so, I just feel like it was just a really botched rollout for various reasons. And a lot of the messaging was, even just about, even when you lost the messaging for the disease, it’s hard to really push for the vaccine.” (FG 5: non-hesitant) | |

| “And she said, oh, well, I was going to get it anyway. But I just don’t like being told what to do…. So I feel like when we start telling people that they have to, it just makes them push back even more against it”. (FG 3: non-hesitant) | |

| “I thought they should still be masked because kids started catching it a lot more and spreading it more freely than the adults were by the time they was opening up the school. So I didn’t like how parents wanted their kids unmasked because a lot of students, if you talk to them, there’s, they’re more afraid than the adults are”. (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “So I am, I think they’ve done a good job with it [school policies]. They’ve kind of taken a middle road. I think it’s being respectful of what the CDC is [recommending]. I think it’s following public health in a framework that, is respectful of personal choice within the CDC framework”. (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “Our school district, I would say I’m highly disappointed in our school district because it [masking policies] became political very quickly and they departed from CDC recommendations immediately. And it stayed on a course of, trying to get the masks out of the schools, trying to allow people to not wear masks, not promote promoting vaccinations. It became very, very ugly and even violent at times in our school district. So it just was kind of a disaster, I would say the whole thing. I’m not in agreement at all of how everything played out in my [school] district”. (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Historic influences, religion, color, and gender, SES | “…but there’s still, you know, some trust issues there that don’t seem to be going anywhere anytime soon issues with the system or the providers or the recommendations. I think it’s a mix of the system and the providers and just being in tune to historical traumas that have happened and that are real and thinking about, okay, was this vaccine tested on black women…? And then we had the information about J and J and the blood clots and that was like a real thing… And so that’s been just a real conversation and hasn’t necessarily helped make these difficult decisions”. (FG 4: non-hesitant) |

| “I had faith in the clinical trial results and I had faith in the process. I mean I probably could have had more faith in the process because I think the government there’s always issues with the government, in ineptitude”. (FG 9: non-UTD) | |

| “You know, I, there’s a component of me where I feel like my faith drives a lot of my choices and, you know, we just pray for peace and protection, each day and, move forward in that way”. (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Advice to Share with Parents | |

|---|---|

| Theme | Quotes |

| Take ownership of decision making and carry out evidence-based research | “I would say, do your research on it and just, you know, if you get it for yourself, then why not get it for your child” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) |

| “Make sure they’re listening to the right voices, like the voices of healthcare professionals and not just random people” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “[I recommend to] continue to be a team player with their health care team, just so that you don’t run into any type of, you know, situations that you regret, whether it’s getting vaccinated or not getting back through” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Share personal experiences and listen with empathy | “What I generally say to parents is, listen, if you don’t want to get your baby vaccinated, and you want to take that risk it is your personal choice. But when, if you ever want to get some additional information, take a walk in the NICU, maybe your view will change. I’m not going to tell you what to do, but I can show you some things” (FG 7: hesitant non-UTD) |

| “I like to ask them why, [and] what they believe to be the truth about the vaccine and why they’re hesitant, and seek to understand whether or not they trust their doctors, so I think that I try not to tell people anything and more focus on trying to elicit information from them” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD). | |

| Emphasize evidence that vaccination prevents serious harm | “As I’ve seen other people, you know, pass away from COVID, you know, I just want them, if you want your children to be safe, it is better to be safe and give them the vaccine than to be sorry and then have to let them go. No parent should bury their children” (FG 2: non-hesitant) |

| “For people who are still as of yet, today, not vaccinated adults. I don’t go into these conversations about children. I’m not going to push my, what I think is right for my kid onto somebody else. I think it’s a very sensitive topic, but when it comes to like, just protecting my friends, you know, adults, I do try to emphasize that there is a tremendous amount of data available around the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines.” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Actions affect others | “I guess I would just tell them to keep your family safe and just don’t think about you. There’s others out here that we need to worry about as well. Like the elderly and children and such. So that’s what I would say to the parents: make a good wise decision. If you choose not to be vaccinated, just take precaution and that’s about it” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) |

| Recommendations to Policy-Makers | |

| Theme | Quotes |

| Make vaccination services and access to information convenient | “I think one of the ways that would probably be advantageous is to do like a mobile center where you take a van around and you go to areas that may be less vaccinated and just make it accessible” (FG 1: non-hesitant) |

| “People generally want to call and get an answer right away…some way to get customer service so you have a question and a place to ask questions and get answers to your questions relatively quickly” (FG 7: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “I think that there’s a lot cooking in the kitchen, but you can’t make people eat what you’re cooking or some people, but I can give you the tools to build a house [and] you [can] choose to build or to choose not to build, but I’m always going up there on the side of caution is for me and my family.” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “I feel like all this, those things [convenient clinics open on nights and weekends] are done in different communities and different things is never going to be enough for some people.” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Leave politics out of policies | “When mask wearing became political, actually that to me was a little bit more frightening. I feel like with vaccines, that’s been an ongoing thing since vaccines have been around. And so, but mask wearing I’m like, that to me, I was just like, okay, we’re doing this for the community and that’s an easy thing, you know?” (FG 5: non-hesitant) |

| “I would say stick to the facts and keep other politicians names and parties out of it so that our community health is not impacted because of, disagreements” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| “The transparency part and not being political, just with really being, humane, and just really caring about the people and understanding that [we] have lessons learned plan from this whole thing. So that if something new does come up again, politics are less out of it. And people’s wellbeing in is going to be the top priority” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Strive for transparency, honesty, and clarity | “I just want them to stop pushing this we’re going back to normal narrative because COVID changed the world so we’re not going back to normal, we’ve got to go forward to something new. We have to live in a new place” (FG 2: non-hesitant) |

| “Listen, really listen to their [health professonal’s] recommendations and don’t make it a political issue. And I think with the messaging, make sure that the messaging reflects that this is not a cold or flu, but it’s an actual disease and it has long-term effects even for kids so that people understand the risks of choosing not to be vaccinated” (FG 9: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Accept that some will not choose vaccination | “See, so you fall on one side of the coin on the mandate that they did the right thing to mandate or you’re not sure. It’s difficult. It’s a hard question for me because it has pushed some of these people into a corner where they’re even more adamant about it” (FG 3: non-hesitant) |

| “I feel like all this, those things [convenient clinics open on nights and weekends] are done in different communities and different things is never going to be enough for some people” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Consider carefully before removing incentives | “I feel like at this rate or what I’ve been seeing for other parents, or, I mean, my dad still has not gotten vaccinated, even though we’ve all told him, he can’t see his six grandchildren. So that always makes me hesitant where I’m like, I don’t know what more of an incentive there should be then seeing your grandchildren to get vaccinated…. I hope that like with parents and caregivers, especially of younger children, it comes down to access to things… Access to restaurants, concerts, traveling…. And I’m fearful that if those things like suddenly get lifted, which I think they’re starting to, it’s just going to backpedal, you know, I’m like, oh, dad let’s travel to Ireland, but you can’t until you’re vaccinated. I’m like, I hope that stays, you know, I don’t know if those types of policies shift” (FG 2: non-hesitant) |

| “For policy makers, you know, personally, I also, I mean, I said, I feel safer in a place where vaccine mandates are required and I think that’s a better way to go about functioning in society” (FG 4: non-hesitant) | |

| Leaders lead by example | “I felt some kind of comfort, even though it was a little cynical when you saw like, Fauci or other, you know, docs in the area, getting on TV, getting a shot. And even though you think, well, they could be getting anything in there, in that needle, but it did also make me feel more confident like these leaders, people telling us to get it” (FG 3: non-hesitant) |

| Listen to communities and recognize one size does not fit all | “I mean, for grown-ups there seems like there’s a lot of pluses to being vaccinated. Like for a long time, we were the only ones who could go to restaurants and things like that. But tell me how it, what’s in it for a seven-year-old, like how does his life get better? I don’t see there being any real policy implications for children…. So I would like there to be know that the Omnicom surge is over, throw us some kind of bone that will make our kids’ lives a little bit better” (FG 2: non-hesitant) |

| “I think that what’s really important for policymakers to understand is that we’re all coming from different backgrounds. We’re coming from different communities and cultures where there might be misunderstandings. There might be a difference in the way that folks have been treated in the health system prior…. And that’s, you know, that helps me better understand how to be more respectful and more understanding of people who have different opinions about the vaccine than I do.” (FG 4 non-hesitant) | |

| “I think it would have been more effective to take a local approach. You know, have a national strategy, but implement it locally so that we’re not doing more harm than good in trying to get this, get the pandemic under control. [An example is] So like lockdowns and putting small business owners, you know, having people lose their lifelong work and say an area where COVID rates were very low, for example, and risk of transmission was very low. You know, also applying those [lockdown policies] fairly, you know, why is Target open, but the mom and pop hardware stores closed” (FG 8: hesitant non-UTD) | |

| Learn from past lessons | “There is a certain amount that we do just have to mandate, right? We mandate seatbelts, we mandate, you know, not having, you know, pipes built with lead in them. You have to mandate things to keep people safe and so I think that our decisions about what we are doing should be really driven by the science and be mandated.” (FG 4: non-hesitant) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, A.K.; Browne, S.; Srivastava, T.; Michel, J.J.; Tan, A.S.L.; Kornides, M.L. Factors Influencing Parental and Individual COVID-19 Vaccine Decision Making in a Pediatric Network. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1277. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081277

Shen AK, Browne S, Srivastava T, Michel JJ, Tan ASL, Kornides ML. Factors Influencing Parental and Individual COVID-19 Vaccine Decision Making in a Pediatric Network. Vaccines. 2022; 10(8):1277. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081277

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Angela K., Safa Browne, Tuhina Srivastava, Jeremy J. Michel, Andy S. L. Tan, and Melanie L. Kornides. 2022. "Factors Influencing Parental and Individual COVID-19 Vaccine Decision Making in a Pediatric Network" Vaccines 10, no. 8: 1277. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081277

APA StyleShen, A. K., Browne, S., Srivastava, T., Michel, J. J., Tan, A. S. L., & Kornides, M. L. (2022). Factors Influencing Parental and Individual COVID-19 Vaccine Decision Making in a Pediatric Network. Vaccines, 10(8), 1277. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10081277