A Latent Profile Analysis of COVID-19 Trusted Sources of Information among Racial and Ethnic Minorities in South Florida

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

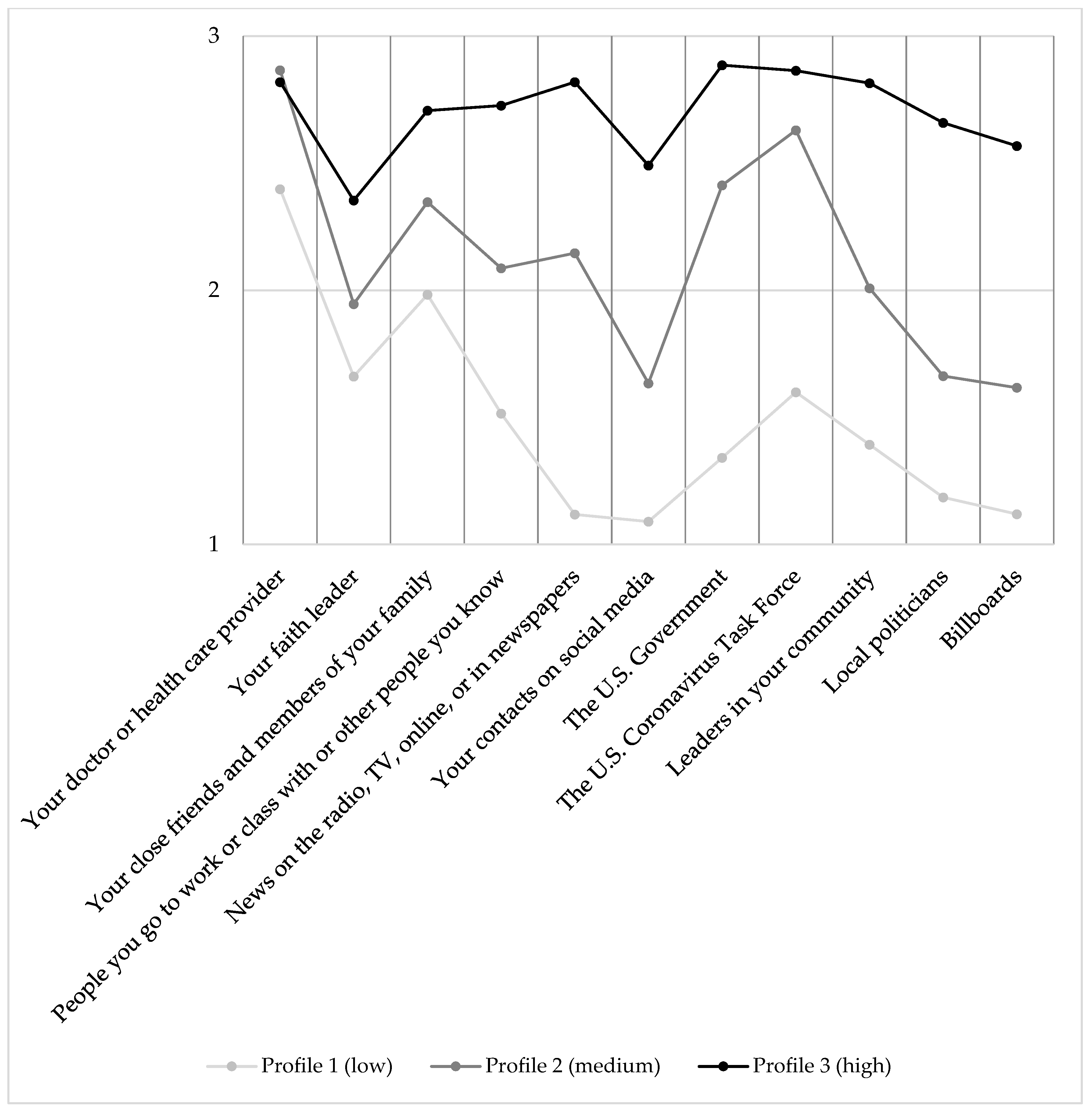

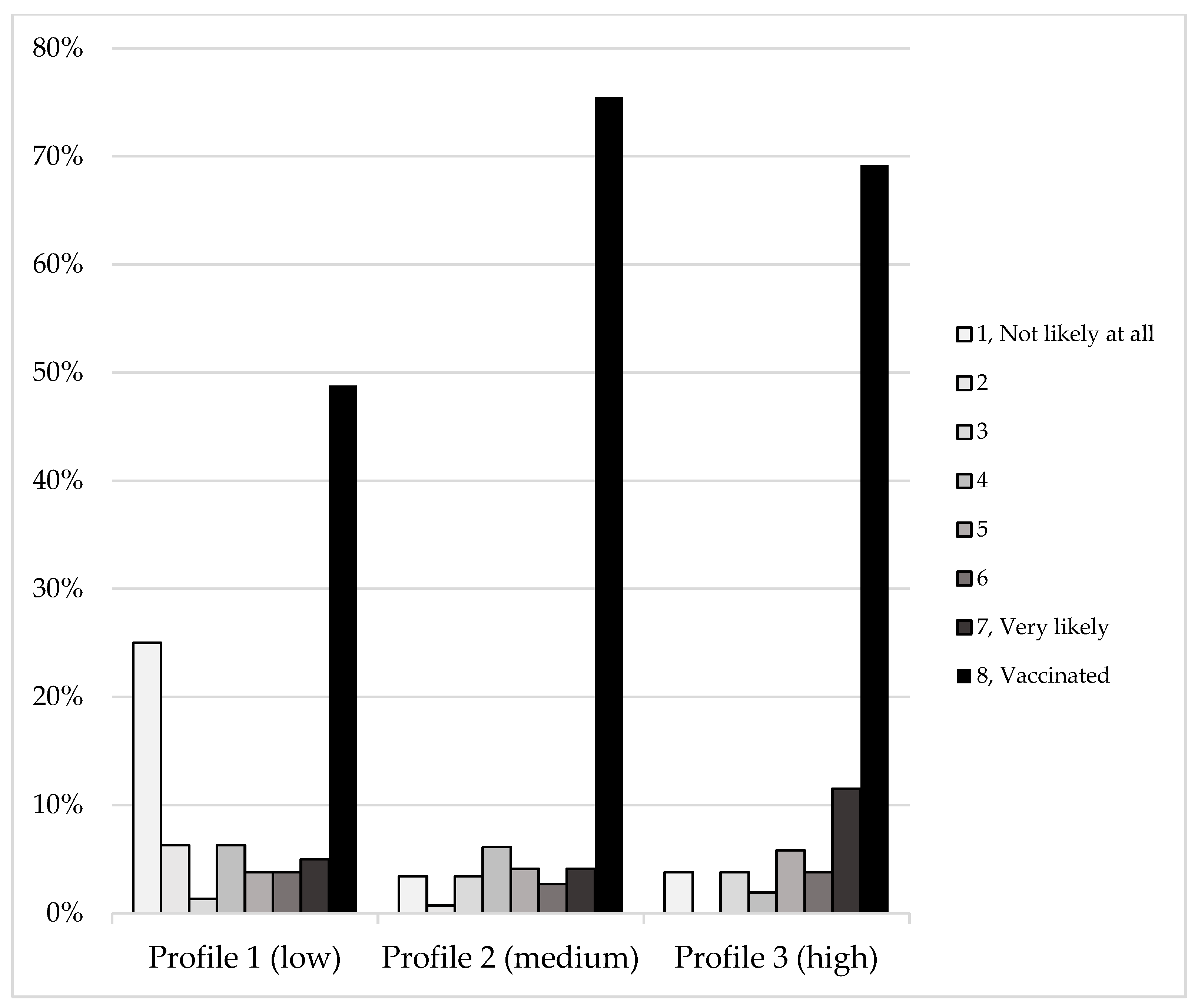

3.2. Latent Profile Analysis

3.3. Regression Analysis and Inferential Statistics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- KFF. KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: December 2020|KFF. 2020. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/report/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-december-2020 (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- CDC. CDC COVID Data Tracker; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-total-admin-rate-total (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Ashby, B.; Best, A. Herd immunity. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R174–R177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, J.L. New Media, Old Messages: Themes in the History of Vaccine Hesitancy and Refusal. AMA J. Ethics 2012, 14, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M.W.; Nápoles, A.M.; Pérez-Stable, E.J. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 323, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcendor, D.J. Racial Disparities-Associated COVID-19 Mortality among Minority Populations in the US. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, T.; Andel, R. Excess Mortality Associated With COVID-19 by Demographic Group: Evidence From Florida and Ohio. Public Health Rep. 2021, 136, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1980; p. 278. Available online: https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10011527857/ (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of plannedbehavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.P.; Magnan, R.E.; Kramer, E.B.; Bryan, A.D. Theory of Planned Behavior Analysis of Social Distancing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Focusing on the Intention–Behavior Gap. Ann. Behav. Med. 2021, 55, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochbaum, G.; Rosenstock, I.; Kegels, S. Health Belief Model. 1952. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C10&q=hochbaum+health+belief+model&btnG=&oq=hochbaum+ (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricorian, K.; Civen, R.; Equils, O. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Misinformation and perceptions of vaccine safety. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 18, 1950504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, A.B.; Elliott, M.H.; Gatewood, S.B.S.; Goode, J.V.R.; Moczygemba, L.R. Perceptions and predictors of intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021, 18, 2593–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latkin, C.A.; Dayton, L.; Yi, G.; Konstantopoulos, A.; Boodram, B. Trust in a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S.: A social-ecological perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 270, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidry, J.P.; Laestadius, L.I.; Vraga, E.K.; Miller, C.A.; Perrin, P.B.; Burton, C.W.; Ryan, M.; Fuemmeler, B.F.; Carlyle, K.E. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 49, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baack, B.N.; Abad, N.; Yankey, D.; Kahn, K.E.; Razzaghi, H.; Brookmeyer, K.; Kolis, J.; Wilhelm, E.; Nguyen, K.H.; Singleton, J.A. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage and Intent Among Adults Aged 18–39 Years—United States, March–May 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.; Purvis, R.S.; Hallgren, E.; Willis, D.E.; Hall, S.; Reece, S.; CarlLee, S.; Judkins, H.; McElfish, P.A. Motivations to Vaccinate Among Hesitant Adopters of the COVID-19 Vaccine. J. Community Health 2021, 47, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, P.F.; Masters, D.; Massey, G. Enablers and barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake: An international study of perceptions and intentions. Vaccine 2021, 39, 5116–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, A.R.; Law, A.V. Will they, or Won’t they? Examining patients’ vaccine intention for flu and COVID-19 using the Health Belief Model. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 17, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaki, D.; Sergay, J. Predicting health behavior in response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Worldwide survey results from early March 2020. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suess, C.; Maddock, J.E.; Dogru, T.; Mody, M.; Lee, S. Using the Health Belief Model to examine travelers’ willingness to vaccinate and support for vaccination requirements prior to travel. Tour. Manag. 2021, 88, 104405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetakis, L.A.; Melas, C. The health belief model predicts vaccination intentions against COVID-19: A survey experiment approach. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Smith, L.E.; Sim, J.; Amlôt, R.; Cutts, M.; Dasch, H.; Rubin, G.J.; Sevdalis, N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: Results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 17, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, K.E.; Dayton, L.; Rouhani, S.; Latkin, C.A. Implications of attitudes and beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines for vaccination campaigns in the United States: A latent class analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eshun-Wilson, I.; Mody, A.; Tram, K.H.; Bradley, C.; Sheve, A.; Fox, B.; Thompson, V.; Geng, E.H. Preferences for COVID-19 vaccine distribution strategies in the US: A discrete choice survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agley, J. Assessing changes in US public trust in science amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health 2020, 183, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, R. NIH Addresses COVID-19 Disparities. JAMA 2021, 325, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carrasquillo, O.; Kobetz-Kerman, E.; Behar-Zusman, V.; Dominguez, S.; Rosa, M.D.; Bastida, E.; Wagner, E.; Campa, A.; Odedina, F.; Shenkman, E.; et al. 46213 Florida Community-Engaged Research Alliance Against COVID-19 in Disproportionately Affected Communities (FL-CEAL): Addressing education, awareness, access, and inclusion of underserved communities in COVID-19 research. J. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 5, 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 6th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA; Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C10&q=Muth%C3%A9n+LK%2C+Muth%C3%A9n+BO%2C+Mplus+User%E2%80%99s+Guide.+8th+edn.+Los+Angeles%2C+Muth%C3%A9n+%26+Muth%C3%A9n.+https%3A%2F%2Fwww.statmodel.com%2F%2C+2017&btnG= (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Miami-Dade Matters: Demographics: County: Miami-Dade. Available online: https://www.miamidadematters.org/demographicdata (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- COVID-19 Vaccinations: County and State Tracker—The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/covid-19-vaccine-doses.html (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Agranov, M.; Elliott, M.; Ortoleva, P. The importance of Social Norms against Strategic Effects: The case of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Econ. Lett. 2021, 206, 109979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida Department of Health. COVID-19: Vaccine Summary. Available online: http://ww11.doh.state.fl.us/comm/_partners/covid19_report_archive/vaccine/vaccine_report_latest.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2021).

| Characteristic | Site 1 | Site 2 | Combined | Miami–Dade County |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 152) | (n = 127) | (N = 279) | Census 1 | |

| Vaccinated * 2 | 110 (72.4%) | 76 (59.8%) | 186 (66.7%) | 79% |

| Not vaccinated | 42 (27.6%) | 51 (40.2%) | 93 (33.3%) | 21% |

| Age | M = 40.6 | M = 40.8 | M = 40.7 | M = 40.5 |

| SD = 15.4 | SD = 14.2 | SD = 14.8 | ||

| 18–82 | 18–80 | 18–82 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 103 (68.2%) | 89 (70.6%) | 192 (69.3%) | 51.42% |

| Male | 47 (31.1%) | 36 (28.6%) | 83 (30%) | 48.58% |

| Nonbinary, genderqueer, or genderfluid | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (0.7%) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 104 (68.4%) | 77 (60.6%) | 181 (64.9%) | 75.8% |

| Black or African American * | 30 (19.7%) | 40 (31.5%) | 70 (25.1%) | 16.42% |

| Asian | 8 (5.3%) | 3 (2.4%) | 11 (3.9%) | 1.53% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.8%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0.21% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.02% |

| Prefer not to answer | 7 (4.6%) | 8 (6.3%) | 15 (5.4%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 102 (68%) | 71 (57.7%) | 173 (63.4%) | 71.51% |

| Race & Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino & Black or African American | 8 (5.3%) | 2 (1.6%) | 10 (3.7%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino & American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.8%) | 3 (1.1%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino & Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Bisexual | 7 (4.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 8 (3%) | |

| Gay | 7 (4.8%) | 2 (1.6%) | 9 (3.3%) | |

| Lesbian | 2 (1.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 3 (1.1%) | |

| Straight | 127 (87.6%) | 120 (95.2%) | 247 (91.1%) | |

| Other | 2 (1.4%) | 2 (1.6%) | 4 (1.5%) | |

| Born in the U.S. | ||||

| Yes | 83 (57.6%) | 70 (57.4%) | 153 (57.5%) | 45.4% |

| English as first language | ||||

| No | 47 (31.3%) | 35 (28.5%) | 82 (30%) | 77% |

| Educational level | ||||

| Less than high school | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 9.39% |

| Some high school | 2 (1.3%) | 3 (2.4%) | 5 (1.8%) | 8.43% |

| High school graduate or GED | 32 (21.3%) | 27 (21.6%) | 59 (21.5%) | 27.31% |

| Associates or technical degree | 28 (18.7%) | 21 (16.8%) | 49 (17.8%) | 9.40% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 54 (36%) | 45 (36%) | 99 (36%) | 19.32% |

| Graduate degree | 34 (22.7%) | 28 (22.4%) | 62 (22.5%) | 8.29% |

| Employment status | ||||

| Working for pay—part time | 34 (22.4%) | 25 (19.7%) | 59 (21.1%) | |

| Working for pay—full time * | 72 (47.4%) | 75 (59.1%) | 147 (52.7%) | |

| Working without pay * | 4 (2.6%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.4%) | |

| On leave | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Unemployed and looking for a job | 12 (7.9%) | 7 (5.5%) | 19 (6.8%) | |

| Unemployed and not looking for a job | 2 (1.3%) | 3 (2.4%) | 5 (1.8%) | |

| Retired | 5 (3.3%) | 4 (3.1%) | 9 (3.2%) | |

| Staying at home, taking care of the home or others | 8 (5.3%) | 7 (5.5%) | 15 (5.4%) | |

| Not able to work because of disability | 1 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Going to school | 23 (15.1%) | 16 (12.6%) | 39 (14%) | |

| Other | 4 (2.6%) | 2 (1.6%) | 6 (2.2%) |

| Covariate | Value | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | 12.39 | 0.002 | 0.2 |

| Age | 1.67 | 0.2 | 0.006 |

| U.S. Born | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.06 |

| Gender | 16.54 | 0.002 | 0.17 |

| Sexual Orientation | 13.51 | 0.1 | 0.16 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 5.32 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| White | 0.533 | 0.77 | 0.04 |

| Black or African American | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.05 |

| Asian | 3.94 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.05 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 2.5 | 0.29 | 0.1 |

| Educational level | 2.57 | 0.99 | 0.07 |

| Income | 8.89 | 0.84 | 0.14 |

| Full-time employment | 3.31 | 0.19 | 0.11 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Langwerden, R.J.; Wagner, E.F.; Hospital, M.M.; Morris, S.L.; Cueto, V.; Carrasquillo, O.; Charles, S.C.; Perez, K.R.; Contreras-Pérez, M.E.; Campa, A.L. A Latent Profile Analysis of COVID-19 Trusted Sources of Information among Racial and Ethnic Minorities in South Florida. Vaccines 2022, 10, 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10040545

Langwerden RJ, Wagner EF, Hospital MM, Morris SL, Cueto V, Carrasquillo O, Charles SC, Perez KR, Contreras-Pérez ME, Campa AL. A Latent Profile Analysis of COVID-19 Trusted Sources of Information among Racial and Ethnic Minorities in South Florida. Vaccines. 2022; 10(4):545. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10040545

Chicago/Turabian StyleLangwerden, Robbert J., Eric F. Wagner, Michelle M. Hospital, Staci L. Morris, Victor Cueto, Olveen Carrasquillo, Sara C. Charles, Katherine R. Perez, María Eugenia Contreras-Pérez, and Adriana L. Campa. 2022. "A Latent Profile Analysis of COVID-19 Trusted Sources of Information among Racial and Ethnic Minorities in South Florida" Vaccines 10, no. 4: 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10040545

APA StyleLangwerden, R. J., Wagner, E. F., Hospital, M. M., Morris, S. L., Cueto, V., Carrasquillo, O., Charles, S. C., Perez, K. R., Contreras-Pérez, M. E., & Campa, A. L. (2022). A Latent Profile Analysis of COVID-19 Trusted Sources of Information among Racial and Ethnic Minorities in South Florida. Vaccines, 10(4), 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10040545