How to Motivate SARS-CoV-2 Convalescents to Receive a Booster Vaccination? Influence on Vaccination Willingness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definitions

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociodemographics

2.3.2. Somatic Factors

2.3.3. Background of Ad Hoc Scales (Vaccination Attitudes, Anti-Corona Measures, Conspiracy Theories)

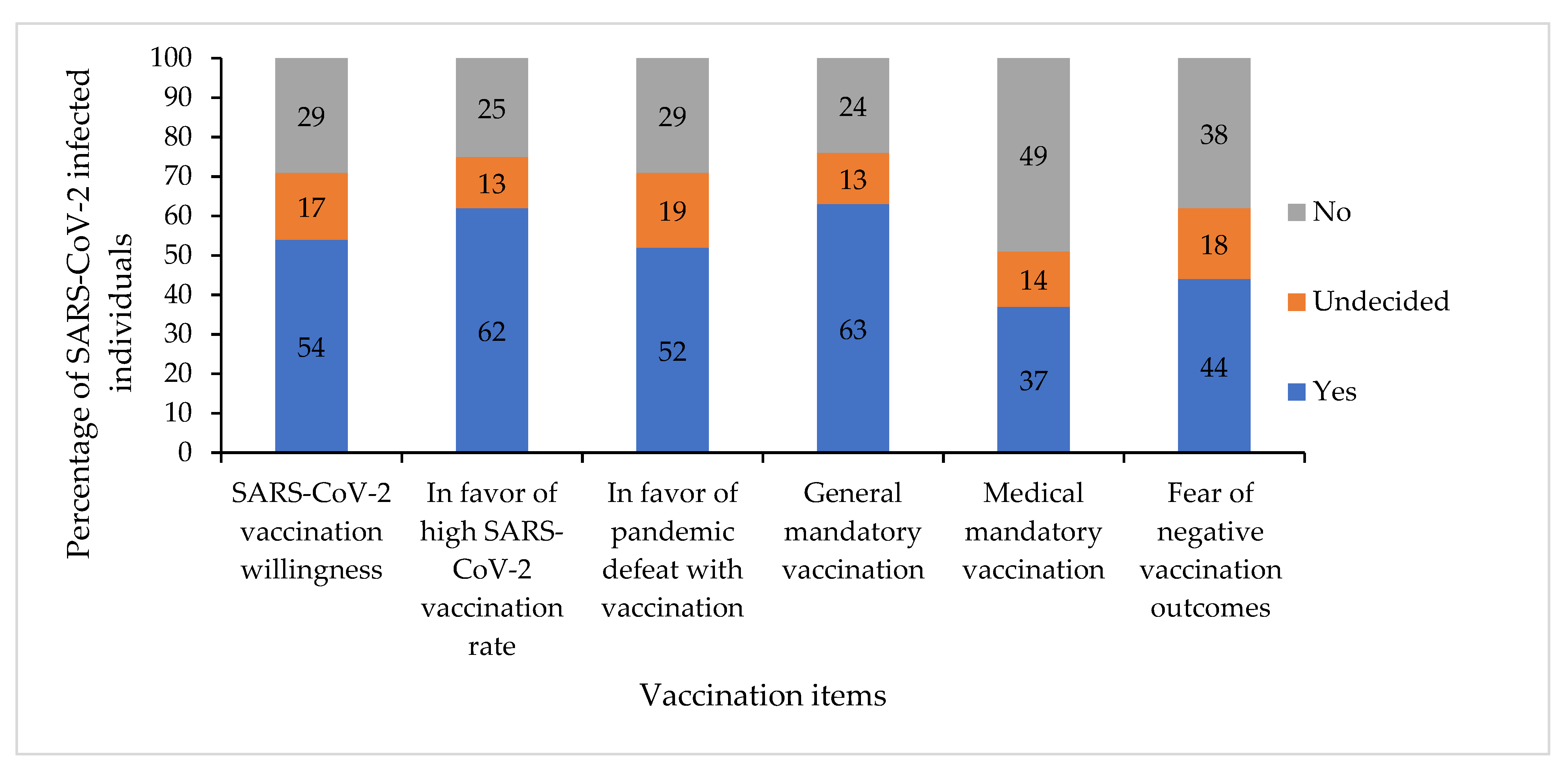

2.3.4. Vaccination Items (Vaccination Willingness and Vaccination Attitudes)

- “I will get vaccinated against the Corona virus.” (=SARS-CoV-2 vaccination willingness).

- “As many people as possible should be vaccinated against the Corona virus in Germany.” (=in favor of a high SARS-CoV-2 vaccination rate)

- “The Corona pandemic can be defeated with vaccinations.” (=in favor of pandemic defeat with vaccination)

- “There should be a general mandatory Corona vaccination in Germany.” (=in favor of general mandatory vaccination)

- “There should be a mandatory Corona vaccination for medical personnel in Germany.” (=in favor of medical mandatory vaccination)

- “I am afraid of negative effects (e.g., long-term damage) of Corona vaccination.” (=fear of negative vaccination outcomes).

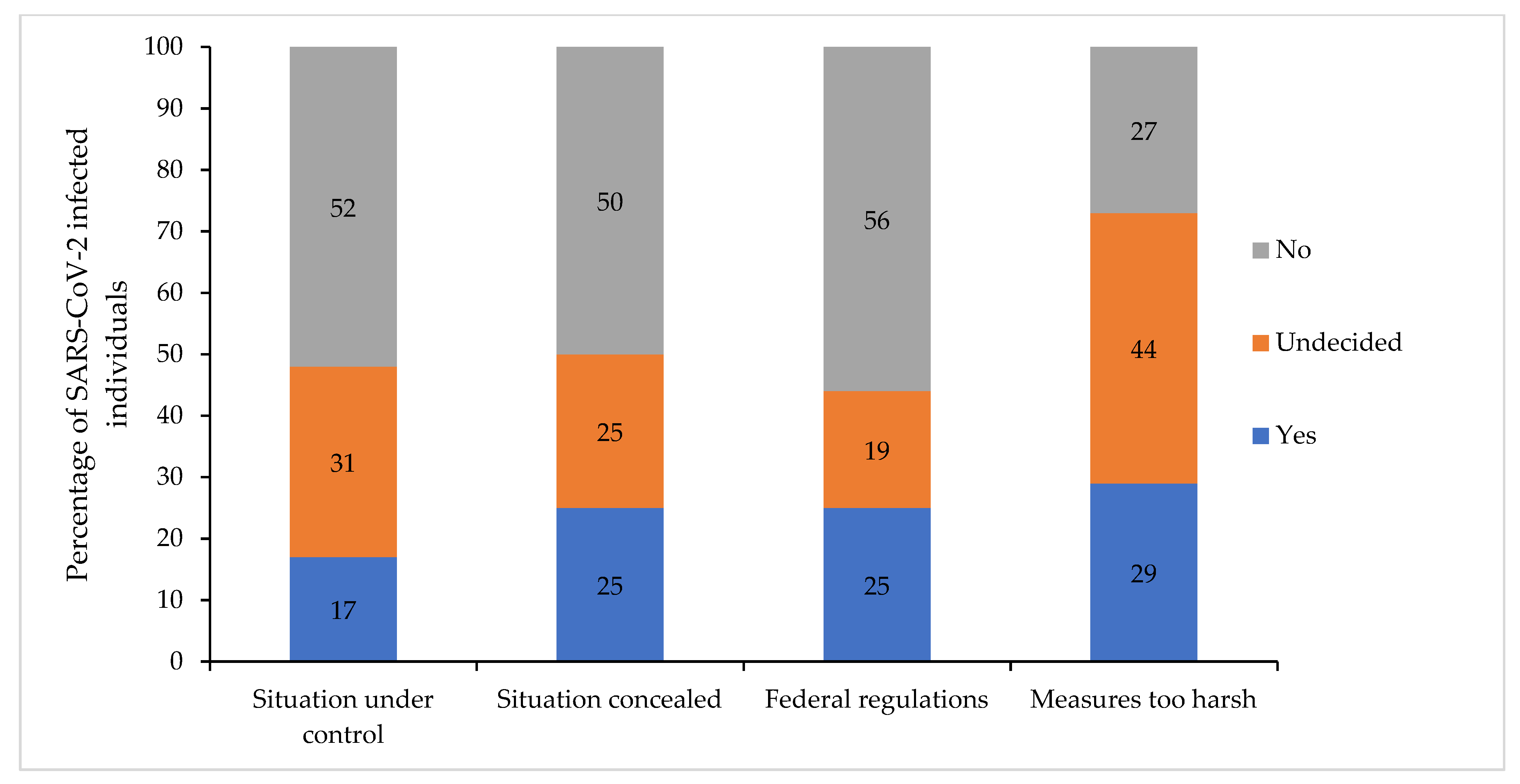

2.3.5. Attitudes Regarding the Government’s Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Measures

- “I have the feeling that the state and the responsible authorities have the situation regarding the Corona virus under control.” (=situation under control)

- “I have a feeling that the state and the relevant authorities are concealing the situation regarding the Corona virus.” (=situation concealed)

- “I think it is reasonable that the federal states each have different regulations. “(=federal regulations)

- “The government’s ordered measures to contain the pandemic are too strict for me.” (=measures too harsh).

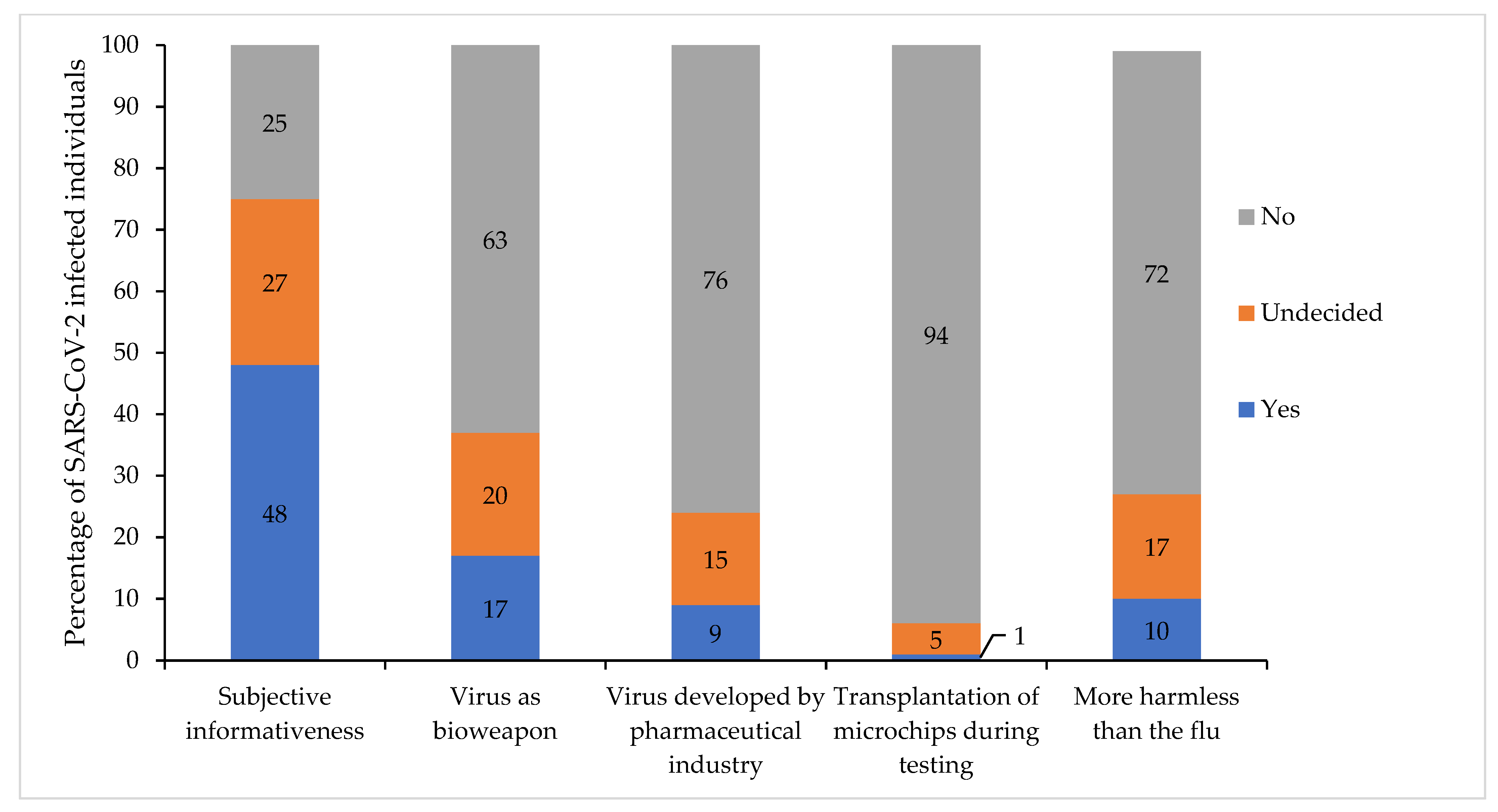

2.3.6. Subjective Informativeness and Susceptibility to Conspiracy Theories

- “I feel sufficiently informed about the Corona virus.” (=subjective informativeness).

- “The Corona virus was cultivated as a bioweapon in a Chinese laboratory.” (=virus as bioweapon)

- “The Corona virus was developed by the pharmaceutical industry to earn a lot of money with the help of vaccines.” (=virus developed by pharmaceutical industry)

- “Corona testing involves the transplantation of microchips.” (=transplantation of microchips during testing)

- “Corona virus infection is more harmless than the flu.” (=more harmless than the flu).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Vaccination Willingness and Attitudes to Further Vaccination Topics

3.3. Vaccination Attitudes Affecting Willingness to Receive Booster Vaccination

3.4. Sociodemographic Aspects Affecting Vaccination Attitudes

3.5. Somatic Factors Affecting Vaccination Attitudes

3.6. Attitudes toward the Government’s Regulations Affecting Vaccination Attitudes

3.7. Subjective Informativeness and Susceptibility to Conspiracy Theories Affecting Vaccination Attitudes

3.8. Prediction of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Willingness

4. Discussion

4.1. Prediction of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Willingness

4.2. Further Factors Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Willingness

4.3. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Willingness in the Context of the COM-B Behavioral Model and Behavior Change Interventions

4.4. Recommendations for Clinical Practice

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- For the first time, it has been shown that the vaccination willingness of home-isolated people with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection with asymptomatic or moderate symptomatic course is only 54%.

- High confidence in the safety of vaccination and high confidence in the effectiveness of vaccination were the strongest predictors of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination willingness.

- Therefore, broad vaccination education should already take place in the phase of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Due to the current psychological processing, affected persons may then be particularly susceptible to motivational vaccination education.

- Motivational vaccination education should be based on the 5C model (psychological reasons for vaccination behavior): “confidence, complacency, constraints, calculation, collective responsibility” [34]. Vaccination education should be demand-driven, low-threshold, and adapted to the specific situation of SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals, considering the vaccine hesitant subgroups mentioned above.

- Individual interventions to increase vaccination willingness can be derived from the behavioral models COM-B [48].

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 26 February 2022).

- World Health Organization (WHO). COVID-19 Case Numbers. Available online: https://who.sprinklr.com/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Standing Committee on Vaccination at the Robert Koch Institute. Epidemiologisches Bulletin 2/2022: Beschluss der STIKO zur 16. Aktualisierung der COVID-19-Impfempfehlung. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2022/Ausgaben/02_22.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Issues Its First Emergency Use Validation for a COVID-19 Vaccine and Emphasizes Need for Equitable Global Access. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/31-12-2020-who-issues-its-first-emergency-use-validation-for-a-covid-19-vaccine-and-emphasizes-need-for-equitable-global-access (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- German Federal Ministry of Health. Impfdashboard of the German Federal Ministry of Health. Available online: https://impfdashboard.de/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Robert Koch Institute. Epidemiologisches Bulletin 27/2021. COVID-19-Zielimpfquote. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2021/Ausgaben/27_21.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Robert Koch Institute. COVID-19-Dashboard. Available online: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/478220a4c454480e823b17327b2bf1d4 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Federal Statistical Office. Current Population of Germany. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Population/Current-Population/_node.html;jsessionid=6C8B5377FCB640FDECE7073D34C11582.live732 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Kellam, P.; Barclay, W. The dynamics of humoral immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 infection and the potential for reinfection. J. Gen. Virol. 2020, 101, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.H.Y.; Tsang, O.T.Y.; Hui, D.S.C.; Kwan, M.Y.W.; Chan, W.H.; Chiu, S.S.; Ko, R.L.W.; Chan, K.H.; Cheng, S.M.S.; Perera, R.; et al. Neutralizing antibody titres in SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okba, N.M.A.; Müller, M.A.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H.; Corman, V.M.; Lamers, M.M.; Sikkema, R.S.; de Bruin, E.; Chandler, F.D.; et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2-Specific Antibody Responses in Coronavirus Disease Patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodda, L.B.; Netland, J.; Shehata, L.; Pruner, K.B.; Morawski, P.A.; Thouvenel, C.D.; Takehara, K.K.; Eggenberger, J.; Hemann, E.A.; Waterman, H.R.; et al. Functional SARS-CoV-2-Specific Immune Memory Persists after Mild COVID-19. Cell 2021, 184, 169–183.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K.K.; Tsang, O.T.; Leung, W.S.; Tam, A.R.; Wu, T.C.; Lung, D.C.; Yip, C.C.; Cai, J.P.; Chan, J.M.; Chik, T.S.; et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: An observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wajnberg, A.; Amanat, F.; Firpo, A.; Altman, D.R.; Bailey, M.J.; Mansour, M.; McMahon, M.; Meade, P.; Mendu, D.R.; Muellers, K.; et al. Robust neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection persist for months. Science 2020, 370, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wölfel, R.; Corman, V.M.; Guggemos, W.; Seilmaier, M.; Zange, S.; Müller, M.A.; Niemeyer, D.; Jones, T.C.; Vollmar, P.; Rothe, C.; et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020, 581, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, J.; Loyal, L.; Frentsch, M.; Wendisch, D.; Georg, P.; Kurth, F.; Hippenstiel, S.; Dingeldey, M.; Kruse, B.; Fauchere, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-reactive T cells in healthy donors and patients with COVID-19. Nature 2020, 587, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Ramirez, S.I.; Mateus, J.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Rawlings, S.A.; Sutherland, A.; Premkumar, L.; Jadi, R.S.; et al. Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell 2020, 181, 1489–1501.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bert, N.; Tan, A.T.; Kunasegaran, K.; Tham, C.Y.L.; Hafezi, M.; Chia, A.; Chng, M.H.Y.; Lin, M.; Tan, N.; Linster, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SARS, and uninfected controls. Nature 2020, 584, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Ye, F.; Cheng, M.L.; Feng, Y.; Deng, Y.Q.; Zhao, H.; Wei, P.; Ge, J.; Gou, M.; Li, X.; et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2-Specific Humoral and Cellular Immunity in COVID-19 Convalescent Individuals. Immunity 2020, 52, 971–977.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, J.; Dowell, A.C.; Pearce, H.; Verma, K.; Long, H.M.; Begum, J.; Aiano, F.; Amin-Chowdhury, Z.; Hoschler, K.; Brooks, T.; et al. Robust SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity is maintained at 6 months following primary infection. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, J.; Graham, C.; Merrick, B.; Acors, S.; Pickering, S.; Steel, K.J.A.; Hemmings, O.; O’Byrne, A.; Kouphou, N.; Galao, R.P.; et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, D.; Brodniak, S.L.; Voegtly, L.J.; Cer, R.Z.; Glang, L.A.; Malagon, F.J.; Long, K.A.; Potocki, R.; Smith, D.R.; Lanteri, C.; et al. A Case of Early Reinfection with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e2827–e2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selhorst, P.; van Ierssel, S.H.; Michiels, J.; Mariën, J.; Bartholomeeusen, K.; Dirinck, E.; Vandamme, S.; Jansens, H.; Ariën, K.K. Symptomatic Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Reinfection of a Healthcare Worker in a Belgian Nosocomial Outbreak Despite Primary Neutralizing Antibody Response. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e2985–e2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillett, R.L.; Sevinsky, J.R.; Hartley, P.D.; Kerwin, H.; Crawford, N.; Gorzalski, A.; Laverdure, C.; Verma, S.C.; Rossetto, C.C.; Jackson, D.; et al. Genomic evidence for reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: A case study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K.K.; Hung, I.F.; Ip, J.D.; Chu, A.W.; Chan, W.M.; Tam, A.R.; Fong, C.H.; Yuan, S.; Tsoi, H.W.; Ng, A.C.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Re-infection by a Phylogenetically Distinct Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Strain Confirmed by Whole Genome Sequencing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e2946–e2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Elslande, J.; Vermeersch, P.; Vandervoort, K.; Wawina-Bokalanga, T.; Vanmechelen, B.; Wollants, E.; Laenen, L.; André, E.; Van Ranst, M.; Lagrou, K.; et al. Symptomatic Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Reinfection by a Phylogenetically Distinct Strain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, V.; Foulkes, S.; Charlett, A.; Atti, A.; Monk, E.J.M.; Simmons, R.; Wellington, E.; Cole, M.J.; Saei, A.; Oguti, B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection rates of antibody-positive compared with antibody-negative health-care workers in England: A large, multicentre, prospective cohort study (SIREN). Lancet 2021, 397, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, A.; Borleri, D.; Farina, C.; Napolitano, G.; Valenti, D.; Rizzi, M.; Maggiolo, F. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is extremely vivacious in subjects with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 4612–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine-Brzostek, S.E.; Yee, J.K.; Sukhu, A.; Qiu, Y.; Rand, S.; Barone, P.D.; Hao, Y.; Yang, H.S.; Meng, Q.H.; Apple, F.S.; et al. Rapid, robust, and sustainable antibody responses to mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in convalescent COVID-19 individuals. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e151477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Health Security Agency. COVID-19 Vaccination: A Guide to Booster Vaccination for Individuals Aged 18 Years and over and Those Aged 16 Years and over Who Are at Risk. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccination-booster-dose-resources/covid-19-vaccination-a-guide-to-booster-vaccination-for-individuals-aged-18-years-and-over#further-information (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- National Centre for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Approved or Authorized in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fvaccines%2Fcovid-19%2Finfo-by-product%2Fclinical-considerations.html#groups-recommended (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Robert Koch Institute. COVID-19 Impfquoten-Monitoring in Deutschland (COVIMO)—Report 8. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Projekte_RKI/COVIMO_Reports/covimo_studie_bericht_8.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Sprengholz, P.; Betsch, C. Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection is linked to lower vaccination intentions. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 6456–6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betsch, C.; Schmid, P.; Heinemeier, D.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C.; Böhm, R. Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccines 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Amer, R.; Maneze, D.; Everett, B.; Montayre, J.; Villarosa, A.R.; Dwekat, E.; Salamonson, Y. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the first year of the pandemic: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, H.; Jia, R.; Ayling, K.; Bradbury, K.; Baker, K.; Chalder, T.; Morling, J.R.; Durrant, L.; Avery, T.; Ball, J.K.; et al. Understanding and addressing vaccine hesitancy in the context of COVID-19: Development of a digital intervention. Public Health 2021, 201, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2020, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Jones, A.; Lesser, I.; Daly, M. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccines 2021, 39, 2024–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snehota, M.; Vlckova, J.; Cizkova, K.; Vachutka, J.; Kolarova, H.; Klaskova, E.; Kollarova, H. Acceptance of a vaccine against COVID-19—A systematic review of surveys conducted worldwide. Bratisl. Lek. Listy. 2021, 122, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Jin, H.; Lin, L. Vaccination against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of acceptability and its predictors. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Failla, G.; Ricciardi, W. Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 40, 101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehal, K.R.; Steendam, L.M.; Campos Ponce, M.; van der Hoeven, M.; Smit, G.S.A. Worldwide Vaccination Willingness for COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomoni, M.G.; Di Valerio, Z.; Gabrielli, E.; Montalti, M.; Tedesco, D.; Guaraldi, F.; Gori, D. Hesitant or Not Hesitant? A Systematic Review on Global COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Different Populations. Vaccines 2021, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wake, A.D. The Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine and Its Associated Factors: “Vaccination Refusal Could Prolong the War of This Pandemic”—A Systematic Review. Risk management and healthcare policy. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 2609–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, F.; Najeeb, H.; Moeed, A.; Naeem, U.; Asghar, M.S.; Chughtai, N.U.; Yousaf, Z.; Seboka, B.T.; Ullah, I.; Lin, C.Y.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the United States: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 770985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fogg, B. A behavior model for persuasive design. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Claremont, CA, USA, 26–29 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.J. A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Health Belief Model Variables in Predicting Behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Betsch, C.; Böhm, R.; Chapman, G.B. Using Behavioral Insights to Increase Vaccination Policy Effectiveness. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 2015, 2, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, E.; Schneider, A.; Zipfel, S.; Stengel, A.; Graf, J. SARS-CoV-2 Positive and Isolated at Home: Stress and Coping Depending on Psychological Burden. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipton, R.; Liberman, J.; Kolodner, K.; Bigal, M.; Dowson, A.; Stewart, W. Migraine Headache Disability and Health-Related Quality-of-Life: A Population-Based Case-Control Study from England. Cephalalgia 2003, 23, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, R.L.; DeRosa, J.T.; Haley, E.C., Jr.; Levin, B.; Ordronneau, P.; Phillips, S.J.; Rundek, T.; Snipes, R.G.; Thompson, J.L.P.; for the GAIN Americas Investigators. Glycine Antagonist in Neuroprotection for Patients with Acute Stroke. GAIN Americas: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2001, 285, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, L.; Chen, Y.; Hu, P.; Wu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Tan, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D. Willingness to Receive SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and Associated Factors among Chinese Adults: A Cross Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. The COVID-19 infodemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel-Stengel, M.; Lohmiller, J.; Schäffeler, N.; Zipfel, S.; Stengel, A. Auswirkungen der COVID-Pandemie auf die Besorgtheit von Patient:innen mit funktionellen gastrointestinalen Symptomen. Z. Gastroenterol. 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing Committee on Vaccination at the Robert Koch Institute. Epidemiologisches Bulletin 5/2021: Beschluss der STIKO zur 2. Aktualisierung der COVID-19-Impfempfehlung. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Archiv/2021/Ausgaben/05_21.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 26 February 2022).

| Vaccination Items | Confidence | Complacency | Constraints | Calculation | Collective Responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “As many people as possible should be vaccinated against the coronavirus in Germany.” | X | X | X | ||

| “The corona pandemic can be defeated with vaccinations.” | X | X | |||

| “There should be a general mandatory Corona vaccination in Germany.” | X | X | X | X | |

| “There should be a mandatory Corona vaccination for medical personnel in Germany.” | X | X | X | X | |

| “I am afraid of negative effects (e.g., long-term damage) of Corona vaccination.” | X | X |

| Sociodemographics | Total (%) Median (Q1–Q3) |

|---|---|

| Age, median | 39.0 (28.0–52.0) |

| Age | |

| Young (18–29) | 64 (28.6%) |

| Middle-aged (30–59) | 135 (60.3%) |

| Old (≥60) | 25 (11.2%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 118 (52.7%) |

| Male | 106 (47.3%) |

| Diverse | 0 (0.0%) |

| Foreign nationality | |

| Yes | 28 (12.5%) |

| No | 196 (87.5%) |

| Highest educational level | |

| Low (lower or higher secondary education) | 145 (64.7%) |

| High (university entrance qualification or university education) | 79 (35.3%) |

| Gross income of the household (€ per year), median | 60,000 (3950–90,000) |

| Financial pandemic-related losses | |

| Yes | 109 (48.7%) |

| No | 115 (51.3%) |

| Children | |

| Yes | 145 (64.7%) |

| No | 79 (35.3%) |

| Total household members | |

| Living alone | 28 (12.5%) |

| Living in pairs | 74 (33.0%) |

| Living at least in threes | 122 (54.5%) |

| Size of municipalities | |

| ≤10,000 | 189 (84.4%) |

| >10,000 | 35 (15.6%) |

| SARS-CoV-2 characteristics | |

| Place of isolation | |

| At home | 224 (100%) |

| Completion of the survey on isolation day, median | 12.0 (10.0–14.0) |

| SARS-CoV-2 associated symptoms | |

| Yes (symptomatic course) | 209 (93.3%) |

| No (asymptomatic course) | 15 (6.7%) |

| Most common SARS-CoV-2 symptoms | |

| headache | 143 (63.8%) |

| sniffles | 141 (62.9%) |

| cough | 138 (61.6%) |

| symptoms of fatigue | 129 (57.6%) |

| body aches | 108 (48.2%) |

| disturbance of the sense of smell | 101 (45.1%) |

| Physical health (0 = very bad, 100 = very good) | |

| Health at the time of the survey | 82.0 (61.0–93.8) |

| Health at the previous disease peak | 48.0 (28.0–70.0) |

| SARS-CoV-2 associated risk factors | |

| Yes | 101 (45.1%) |

| No | 123 (54.9%) |

| SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Willingness | In Favor of a High SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Rate | In Favor of Pandemic Defeat with Vaccination | In Favor of General Mandatory Vaccination | In Favor of Medical Mandatory Vaccination | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In favor of a high SARS-CoV-2 vaccination rate | r | 0.727 | ||||

| p | <0.001 *** | |||||

| In favor of pandemic defeat with vaccination | r | 0.759 | 0.731 | |||

| p | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | ||||

| In favor of general mandatory vaccination | r | 0.547 | 0.529 | 0.527 | ||

| p | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |||

| In favor of medical mandatory vaccination | r | 0.464 | 0.498 | 0.419 | 0.739 | |

| p | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | ||

| Fear of negative vaccination outcomes | r | −0.463 | −0.416 | −0.366 | −0.371 | −0.323 |

| p | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | |

| Items | Correlation with SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Willingness | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic aspects | ||

| Age | r | 0.308 |

| p | <0.001 *** | |

| Number of household members | r | −0.022 |

| p | 0.746 | |

| Income (free text) | r | 0.226 |

| p | 0.001 ** | |

| Somatic factors | ||

| Current health | r | −0.002 |

| p | 0.972 | |

| Worst health | r | −0.007 |

| p | 0.917 | |

| Symptoms | r | 0.056 |

| p | 0.407 | |

| Risk factors | r | −0.062 |

| p | 0.359 | |

| Attitudes toward governmental regulations | ||

| Situation under control | r | 0.278 |

| p | <0.001 *** | |

| Situation concealed | r | −0.288 |

| p | <0.001 *** | |

| Federal regulations | r | 0.096 |

| p | 0.152 | |

| Measures too harsh | r | −0.222 |

| p | 0.001 ** | |

| Subjective informativeness and susceptibility to conspiracy theories | ||

| Subjective informativeness | r | 0.315 |

| p | <0.001 *** | |

| Virus as bioweapon | r | −0.136 |

| p | 0.041 * | |

| Virus developed by pharmaceutical industry | r | −0.220 |

| p | 0.001 ** | |

| Transplantation of microchips during testing | r | −0.175 |

| p | 0.009 ** | |

| More harmless than the flu | r | −0.240 |

| p | <0.001 *** |

| Regression Coefficient | Standard Error | Significance | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence INTERVAL for Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory Variable | B | SE | p | Exp(B) | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Sociodemographic aspects | ||||||

| Age | 0.800 | |||||

| Age a | −0.071 | 0.724 | 0.922 | 0.932 | 0.225 | 3.854 |

| Age b | −0.648 | 1.084 | 0.550 | .523 | 0.063 | 4.377 |

| Nationality c | 1.184 | 0.839 | 0.158 | 3.269 | 0.631 | 16.941 |

| Income | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.755 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Children d | 1.116 | 0.647 | 0.084 | 3.054 | 0.860 | 10.851 |

| Vaccination attitudes | ||||||

| In favor of a high SARS-CoV-2 vaccination rate | 0.025 | 0.010 | 0.015 * | 1.025 | 1.005 | 1.046 |

| In favor of pandemic defeat with vaccination | 0.048 | 0.011 | <0.001 *** | 1.049 | 1.027 | 1.071 |

| In favor of general mandatory vaccination | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.244 | 1.010 | 0.993 | 1.028 |

| In favor of medical mandatory vaccination | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.569 | 1.005 | 0.989 | 1.021 |

| Fear of negative vaccination outcomes | −0.017 | 0.008 | 0.031 * | 0.983 | 0.968 | 0.998 |

| Attitudes toward the government’s regulations | ||||||

| Situation under control | −0.003 | 0.011 | 0.793 | 0.997 | 0.977 | 1.018 |

| Situation concealed | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.209 | 1.011 | 0.994 | 1.029 |

| Measures too harsh | −0.002 | 0.010 | 0.819 | 0.998 | 0.978 | 1.018 |

| Subjective informativeness and conspiracy theories | ||||||

| Subjective informativeness | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.322 | 1.010 | 0.990 | 1.030 |

| Virus as bioweapon | −0.011 | 0.009 | 0.220 | 0.989 | 0.972 | 1.007 |

| Virus developed by pharmaceutical industry | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.839 | 1.002 | 0.980 | 1.025 |

| Transplantation of microchips during testing | −0.015 | 0.018 | 0.415 | 0.986 | 0.952 | 1.021 |

| More harmless than the flu | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.610 | 1.005 | 0.986 | 1.024 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kowalski, E.; Stengel, A.; Schneider, A.; Goebel-Stengel, M.; Zipfel, S.; Graf, J. How to Motivate SARS-CoV-2 Convalescents to Receive a Booster Vaccination? Influence on Vaccination Willingness. Vaccines 2022, 10, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030455

Kowalski E, Stengel A, Schneider A, Goebel-Stengel M, Zipfel S, Graf J. How to Motivate SARS-CoV-2 Convalescents to Receive a Booster Vaccination? Influence on Vaccination Willingness. Vaccines. 2022; 10(3):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030455

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowalski, Elias, Andreas Stengel, Axel Schneider, Miriam Goebel-Stengel, Stephan Zipfel, and Johanna Graf. 2022. "How to Motivate SARS-CoV-2 Convalescents to Receive a Booster Vaccination? Influence on Vaccination Willingness" Vaccines 10, no. 3: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030455

APA StyleKowalski, E., Stengel, A., Schneider, A., Goebel-Stengel, M., Zipfel, S., & Graf, J. (2022). How to Motivate SARS-CoV-2 Convalescents to Receive a Booster Vaccination? Influence on Vaccination Willingness. Vaccines, 10(3), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10030455