Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Punjab, Pakistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Development and Validity of the Survey Instrument

2.3. Sample and Sampling

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of COVID-19 Patients by Vaccination Status

3.2. COVID-19 Vaccination-Related Factors by Vaccination Status

3.3. Construct Validity and Reliability of Vaccine Hesitancy Questionnaire

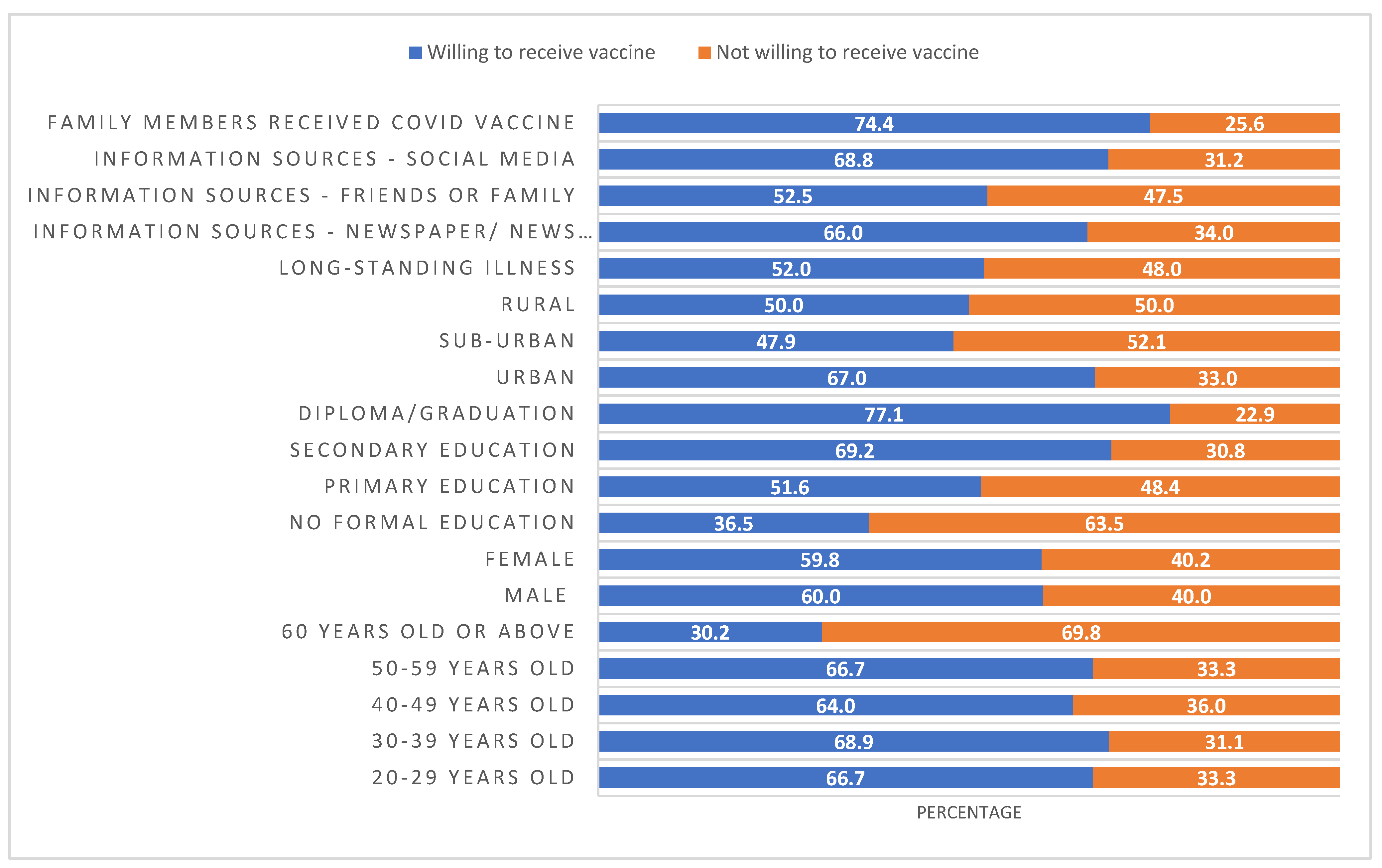

3.4. Patients’ Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine and Hesitancy

3.5. Factors Associated with Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yazdani, A.T.; Muhammad, A.; Nisar, M.I.; Khan, U.; Shafiq, Y. Unveiling and addressing implementation barriers to routine immunization in the peri-urban slums of Karachi, Pakistan: A mixed-methods study. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2021, 19, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Command and Operation Center (NCOC). Important Guidelines. Available online: https://ncoc.gov.pk/COVID-vaccination-en.php (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Voice of America. Pakistan Starts COVID-19 Inoculation. Available online: https://www.voanews.com/COVID-19-pandemic/pakistan-starts-COVID-19-inoculation-drive (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Aljazeera. Pakistan Kicks Off COVID Vaccination Drive for Senior Citizens. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/10/pakistan-kicks-off-senior-citizen-coronavirus-vaccinations (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Piraveenan, M.; Sawleshwarkar, S.; Walsh, M.; Zablotska, I.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Farooqui, H.H.; Bhatnagar, T.; Karan, A.; Murhekar, M.; Zodpey, S.; et al. Optimal governance and implementation of vaccination programmes to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021, 8, 210429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Command and Operation Center (NCOC). Get Vaccinated–Save Live. 2021. Available online: https://ncoc.gov.pk/ (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Khan, Y.H.; Mallhi, T.H.; Alotaibi, N.H.; Alzarea, A.I.; Alanazi, A.S.; Tanveer, N.; Hashmi, F.K. Threat of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Pakistan: The need for measures to neutralize misleading narratives. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.; Malik, J.; Ishaq, U. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in Pakistan among health care workers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Disaster Management Authority. Overview. Available online: http://cms.ndma.gov.pk/ (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Aljazeera. Vaccine Hesitancy in Pakistan Heightens Risk of COVID Resurgence. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/5/in-pakistan-vaccine-hesitancy-heightens-risk-of-COVID-19-resurge (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- MacDonald, N.E.; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís Arce, J.S.; Warren, S.S.; Meriggi, N.F.; Scacco, A.; McMurry, N.; Voors, M.; Syunyaev, G.; Malik, A.A.; Aboutajdine, S.; Adeojo, O.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low-and middle-income countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Nawaz, F.; Idnan, M.; Hayee, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Pakistan: An Analysis of Challenges and Mitigations. Microbes Infect. Dis. 2021, 2, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.J.; Saqlain, M.; Tariq, W.; Waheed, S.; Tan, S.H.S.; Nasir, S.I.; Ullah, I.; Ahmed, A. Population preferences and attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination: A cross-sectional study from Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashif, M.; Fatima, I.; Ahmed, A.M.; Ali, S.A.; Memon, R.S.; Afzal, M.; Saeed, U.; Gul, S.; Ahmad, J.; Malik, F.; et al. Perception, willingness, barriers, and hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccine in Pakistan: Comparison between healthcare workers and general population. Cureus 2021, 13, e19106. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, T.; Gogolewski, K.; Bodych, M.; Gambin, A.; Giordano, G.; Cuschieri, S.; Czypionka, H.; Perc, M.; Petelos, E.; Rosińska, M.; et al. Risk assessment of COVID-19 epidemic resurgence in relation to SARS-CoV-2 variants and vaccination passes. Commun. Med. 2022, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.; MacDonald, N.E.; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Diagnosing the determinants of vaccine hesitancy in specific subgroups: The Guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes (TIP). Vaccine 2015, 33, 4176–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olit, D.F.; Hungler, B.P. Nursing Research. Methods, Appraisal and Utilization, 3rd ed.; Lippincott Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou, G. Translation, Adaptation and Validation Process of Research Instruments. In Individualized Care; Suhonen, R., Stolt, M., Papastavrou, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, C.; Furnham, A. Designing and Analysing Questionnaires and Surveys: A Manual for Health Professionals and Administrators; Whurr Publishers Ltd: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Waston, R.; Thompson, D.R. Use of factor analysis in Journal of Advanced Nursing: Literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 55, 330–341. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, T.R.; Brown, J.K. Ten measurement commandments that often should be broken. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridharan, B.; Deng, H.; Kirk, J.; Corbitt, B. Structural Equation Modeling for Evaluating the User Perceptions of E-Learning Effectiveness in Higher Education. ECIS 2010 Proceedings. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2010/59 (accessed on 1 January 2010).

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Printice-Hall Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nunally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bhopal, S.; Nielsen, M. Vaccine hesitancy in low-and middle-income countries: Potential implications for the COVID-19 response. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 113–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H.; Wong, P.F.; Lee, H.Y.; AbuBakar, S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundagowa, P.T.; Tozivepi, S.N.; Chiyaka, E.T.; Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F.; Makurumidze, R. Assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Zimbabweans: A rapid national survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueangpoon, K.; Inchan, C.; Kaewmuneechoke, P.; Rattana, P.; Budsratid, S.; Japakiya, S.; Ngamchaliew, P.; Vichitkunakorn, P. Self-Reported COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Willingness to Pay: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Thailand. Vaccines 2022, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danabal, K.G.M.; Magesh, S.S.; Saravanan, S.; Gopichandran, V. Attitude towards COVID 19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy in urban and rural communities in Tamil Nadu, India–a community based survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zintel, S.; Flock, C.; Arbogast, A.L.; Forster, A.; von Wagner, C.; Sieverding, M. Gender differences in the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Z. Gesundh Wiss, 2022; epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihun, G.; Walle, Z.; Berhanu, L.; Teshome, D. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and determinant factors among patients with chronic disease visiting Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northeastern Ethiopia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2021, 15, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piltch-Loeb, R.; Savoia, E.; Goldberg, B.; Hughes, B.; Verhey, T.; Kayyem, J.; Miller-Idriss, C.; Testa, M. Examining the effect of information channel on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trent, M.; Seale, H.; Chughtai, A.A.; Salmon, D.; MacIntyre, C.R. Trust in government, intention to vaccinate and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A comparative survey of five large cities in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2498–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/ (accessed on 28 January 2022).

| Variables | Non-Vaccinated COVID-19 Patients n (%) | Vaccinated COVID-19 Patients n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.2 (12.8) | 50.4 (11.4) | 0.063 |

| Age Groups | |||

| 20–29 | 33 (91.7) | 3 (8.3) | 0.067 |

| 30–39 | 45 (91.8) | 4 (8.2) | |

| 40–49 | 111 (81.0) | 26 (19.0) | |

| 50–59 | 81 (82.7) | 17 (17.3) | |

| 60 or above | 52 (80.0) | 13 (20.0) | |

| Gender (n = 384) | |||

| Male | 189 (86.7) | 29 (13.3) | 0.060 |

| Female | 132 (79.5) | 34 (20.5) | |

| Education (n = 385) | |||

| No formal education | 73 (86.9) | 11 (13.1) | 0.443 |

| Primary | 62 (81.6) | 14 (18.4) | |

| Secondary | 117 (80.7) | 28 (19.3) | |

| Diploma/Graduation | 70 (87.5) | 10 (12.5) | |

| Occupation (n = 384) | |||

| Unemployed | 52 (16.2) | 7 (11.1) | 0.479 |

| Self-employed | 91 (28.3) | 17 (27.0) | |

| Employed | 103 (32.1) | 19 (30.2) | |

| Retired | 75 (23.4) | 20 (31.7) | |

| Marital status (n = 384) | |||

| Unmarried/never married | 29 (90.6) | 3 (9.4) | 0.330 |

| Married | 227 (81.9) | 50 (18.1) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 65 (86.7) | 10 (13.3) | |

| Geographical location (n = 384) | |||

| Urban | 194 (81.9) | 43 (18.1) | 0.022 |

| Sub-urban | 48 (77.4) | 14 (22.6) | |

| Rural | 79 (92.9) | 6 (7.1) | |

| Long-standing illness (n = 384) | |||

| No | 199 (84.7) | 36 (15.3) | 0.470 |

| Yes | 122 (81.9) | 27 (18.1) |

| Variables | Non-Vaccinated COVID-19 Patients n (%) | Vaccinated COVID-19 Patients n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family or friends received vaccines (n = 385) | |||

| No | 68 (87.2) | 10 (12.8) | 0.344 |

| Yes | 254 (82.7) | 53 (17.3) | |

| Received information about COVID-19 vaccines (n = 385) | |||

| No | 23 (79.3) | 6 (20.7) | 0.525 |

| Yes | 299 (84.0) | 57 (16.0) | |

| Information sources (n = 385) | |||

| No information received | 14 (100) | 0 (0.0) | 0.093 |

| Newspaper/news channel | 196 (83.1) | 40 (16.9) | |

| Friends or family | 80 (80.8) | 19 (19.2) | |

| Social media | 32 (88.9) | 4 (11.1) | |

| Willing to receive a vaccine (n = 322) | |||

| No | 128 (39.8) | - | - |

| Yes | 194 (60.2) | - | - |

| Trust information shared on social media about the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines (n = 354) | |||

| Yes | 120 (85.7) | 20 (14.3) | 0.235 |

| No | 173 (80.8) | 41 (19.2) | |

| Questionnaire Domains | Number of Items | Scale (Possible Range) | Number of COVID-19 Patients | Mean (SD) | Skewness | Percent Variance | Reliability Coefficients Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hesitancy in receiving COVID-19 vaccine | 3 | Strongly agree to Strongly disagree (1–5) | 385 | 9.1 (5.1) | −0.119 | 76.4 | 0.91 |

| Trust in COVID-19 vaccine | 8 | Strongly agree to Strongly disagree (1–5) | 385 | 23.5 (13.9) | 0.216 | 9.4 | 0.97 |

| Total | 11 | Strongly agree to Strongly disagree (1–5) | 385 | 32.6 (17.9) | 0.158 | 85.8 | 0.97 |

| Variables | Not willing to receive n (%) | Willing to receive n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 50.5 (14.1) | 44.9 (11.3) | 0.001 |

| Age Groups | |||

| 20–29 | 11 (33.3) | 22 (66.7) | 0.001 |

| 30–39 | 14 (31.1) | 31 (68.9) | |

| 40–49 | 40 (36.0) | 71 (64.0) | |

| 50–59 | 27 (33.3) | 54 (66.7) | |

| 60 or above | 36 (69.2) | 16 (30.8) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 75 (39.7) | 114 (60.3) | 0.512 |

| Female | 53 (40.2) | 79 (59.8) | |

| Education | |||

| No formal education | 46 (63.0) | 27 (37.0) | 0.001 |

| Primary | 30 (48.4) | 32 (51.6) | |

| Secondary | 36 (30.8) | 81 (69.2) | |

| Diploma/Graduation | 16 (22.9) | 54 (77.1) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 34 (65.4) | 18 (34.6) | 0.001 |

| Self-employed | 31 (34.1) | 60 (65.9) | |

| Employed | 28 (27.2) | 75 (72.8) | |

| Retired | 35 (46.7) | 40 (53.3) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried/never married | 10 (34.5) | 19 (65.5) | 0.003 |

| Married | 80 (35.2) | 147 (64.8) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 38 (58.5) | 27 (41.5) | |

| Geographical location | |||

| Urban | 64 (33.0) | 130 (67.0) | 0.007 |

| Sub-urban | 25 (52.1) | 23 (47.9) | |

| Rural | 39 (49.4) | 40 (50.6) | |

| Long-standing illness | |||

| No | 70 (35.2) | 129 (64.8) | 0.019 |

| Yes | 58 (47.5) | 64 (52.5) |

| Not Received Vaccine (Referent) | Received COVID-19 Vaccine | Agreement—No or Lower Hesitancy (Referent) | Disagreement—Higher Hesitancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| Age categories | ||||||

| 20–29 | 1.0 | 0.10 (0.01–0.72) | 0.001 | 1.0 | 0.56 (0.10–3.03) | 0.501 |

| 30–39 | 1.0 | 0.10 (0.14–0.85) | 0.021 | 1.0 | 1.53 (0.33–7.18) | 0.588 |

| 40–49 | 1.0 | 0.26 (0.15–0.96) | 0.040 | 1.0 | 1.22 (0.32–4.38) | 0.770 |

| 50–59 | 1.0 | 0.31 (0.10–1.02) | 0.053 | 1.0 | 2.28 (0.64–8.17) | 0.204 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.0 | 0.54 (0.30–0.96) | 0.037 | 1.0 | 3.56 (1.67–7.59) | 0.001 |

| No family members received the vaccine | 1.0 | 0.55 (0.25–1.24) | 0.152 | 1.0 | 1.06 (0.34–3.29) | 0.915 |

| Not willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine | - | - | - | 1.0 | 53.45 (23.78–120.16) | 0.001 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 1.0 | 4.82 (0.82–28.41) | 0.083 | 1.0 | 0.66 (0.14–3.07) | 0.597 |

| Married | 1.0 | 3.51 (1.33–9.22) | 0.011 | 1.0 | 1.23 (0.44–3.39) | 0.687 |

| Education | ||||||

| No formal education | 1.0 | 0.60 (0.19–1.89) | 0.387 | 1.0 | 5.26 (1.85–14.97) | 0.002 |

| Primary education | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.38–2.66) | 0.996 | 1.0 | 2.59 (0.92–7.56) | 0.070 |

| Secondary education | 1.0 | 1.33 (0.58–3.07) | 0.499 | 1.0 | 1.99 (0.80–4.91) | 0.136 |

| Geographical location | ||||||

| Urban | 1.0 | 3.16 (1.27–7.87) | 0.013 | 1.0 | 2.14 (0.88–5.20) | 0.095 |

| Sub-urban | 1.0 | 3.88 (1.35–11.15) | 0.012 | 1.0 | 2.05 (0.63–6.65) | 0.233 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baraka, M.A.; Manzoor, M.N.; Ayoub, U.; Aljowaie, R.M.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Zaidi, S.T.R.; Salman, M.; Kow, C.S.; Aldeyab, M.A.; Hasan, S.S. Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Punjab, Pakistan. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10101640

Baraka MA, Manzoor MN, Ayoub U, Aljowaie RM, Mustafa ZU, Zaidi STR, Salman M, Kow CS, Aldeyab MA, Hasan SS. Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Punjab, Pakistan. Vaccines. 2022; 10(10):1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10101640

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaraka, Mohamed A., Muhammad Nouman Manzoor, Umar Ayoub, Reem M. Aljowaie, Zia Ul Mustafa, Syed Tabish Razi Zaidi, Muhammad Salman, Chia Siang Kow, Mamoon A. Aldeyab, and Syed Shahzad Hasan. 2022. "Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Punjab, Pakistan" Vaccines 10, no. 10: 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10101640

APA StyleBaraka, M. A., Manzoor, M. N., Ayoub, U., Aljowaie, R. M., Mustafa, Z. U., Zaidi, S. T. R., Salman, M., Kow, C. S., Aldeyab, M. A., & Hasan, S. S. (2022). Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy among Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Punjab, Pakistan. Vaccines, 10(10), 1640. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10101640