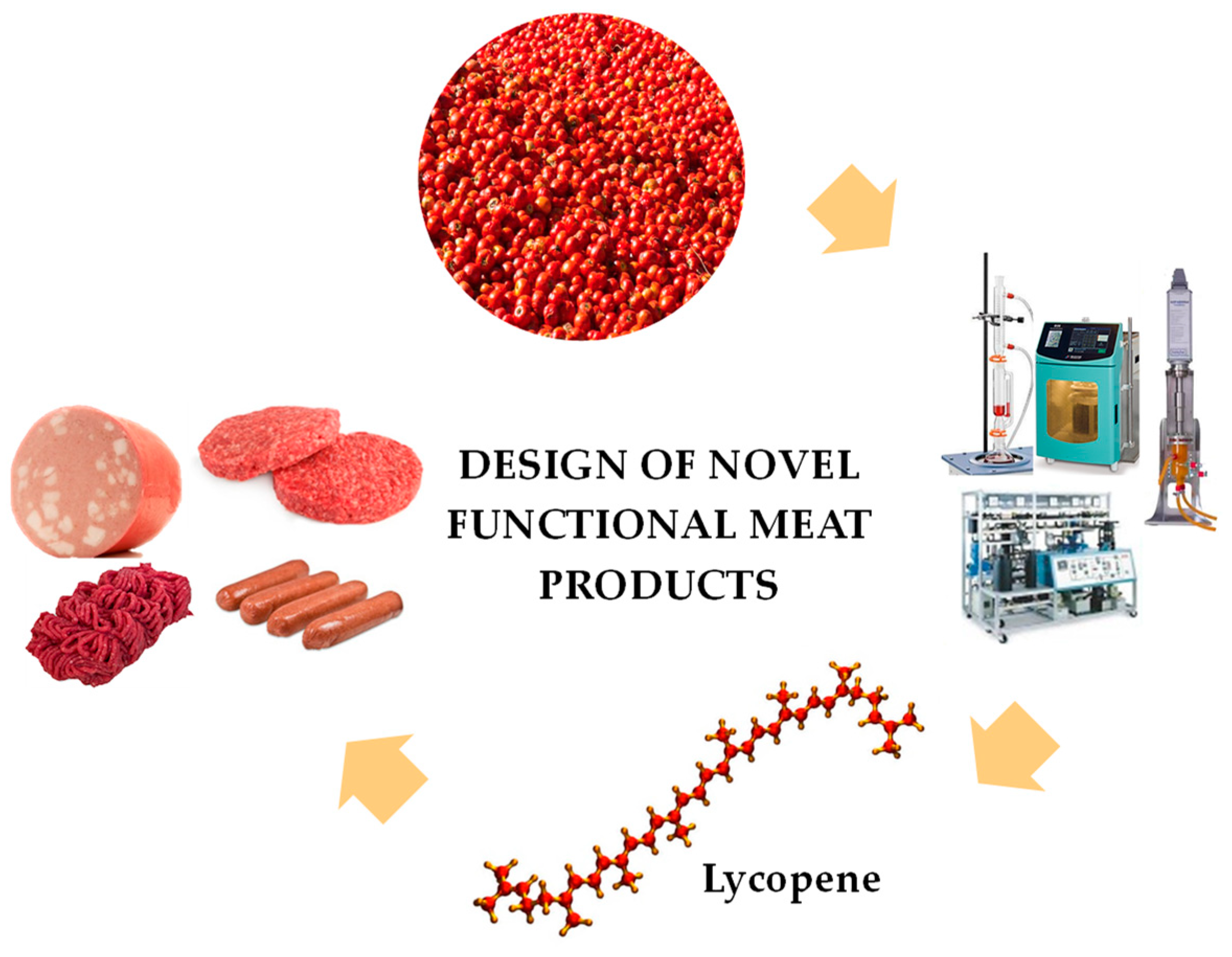

Tomato as Potential Source of Natural Additives for Meat Industry. A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Bioactive Compounds Present in Tomato

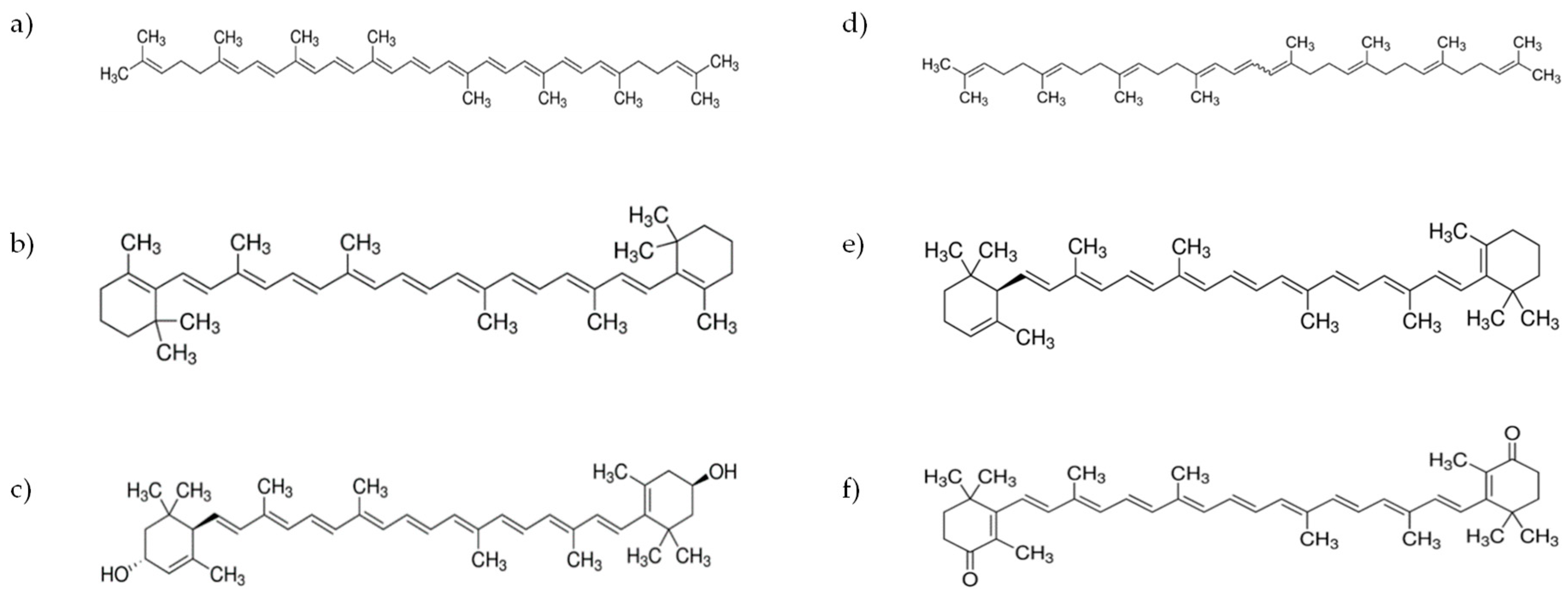

2.1. Carotenoids

2.1.1. Lycopene

2.1.2. β-Carotene

2.2. Phenolic Compounds

2.3. Vitamins

2.4. Glycoalkaloids

3. Carotenoids Extraction Techniques

3.1. Conventional Techniques: Organic Solvent Extraction

3.2. Green Technique: Supercritical Fluid Extraction

4. Use of Tomato in Meat Products

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Gagaoua, M.; Barba, F.J.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. A comprehensive review on lipid oxidation in meat and meat products. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deda, M.S.; Bloukas, J.G.; Fista, G.A. Effect of tomato paste and nitrite level on processing and quality characteristics of frankfurters. Meat Sci. 2007, 76, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lourenço, S.C.; Moldão-Martins, M.; Alves, V.D. Antioxidants of natural plant origins: From sources to food industry applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barden, L.; Decker, E.A. Lipid Oxidation in Low-moisture Food: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 2467–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, A.I.; Petrón, M.J.; Adámez, J.D.; López, M.; Timón, M.L. Food by-products as potential antioxidant and antimicrobial additives in chill stored raw lamb patties. Meat Sci. 2017, 129, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateiro, M.; Vargas, F.C.; Chincha, A.A.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Strozzi, I.; Rocchetti, G.; Barba, F.J.; Domínguez, R.; Lucini, L.; do Amaral Sobral, P.J.; et al. Guarana seed extracts as a useful strategy to extend the shelf life of pork patties: UHPLC-ESI/QTOF phenolic profile and impact on microbial inactivation, lipid and protein oxidation and antioxidant capacity. Food Res. Int. 2018, 114, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Barba, F.J.; Gómez, B.; Putnik, P.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Pateiro, M.; Santos, E.M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Active packaging films with natural antioxidants to be used in meat industry: A review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Barba, F.J.; Putnik, P.; Kovačević, D.B.; Shpigelman, A.; Granato, D.; Franco, D. Berries extracts as natural antioxidants in meat products: A review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doménech-Asensi, G.; García-Alonso, F.J.; Martínez, E.; Santaella, M.; Martín-Pozuelo, G.; Bravo, S.; Periago, M.J. Effect of the addition of tomato paste on the nutritional and sensory properties of mortadella. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.E.; Canonico, I.; Allen, P. Effects of organic tomato pulp powder and nitrite level on the physicochemical, textural and sensory properties of pork luncheon roll. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.S.; Jin, S.K.; Yang, M.R.; Chu, G.M.; Park, J.H.; Rashid, R.H.I.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, S.N. Efficacy of tomato powder as antioxidant in cooked pork patties. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nour, V.; Panaite, T.D.; Ropota, M.; Turcu, R.; Trandafir, I.; Corbu, A.R. Nutritional and bioactive compounds in dried tomato processing waste. CyTA J. Food 2018, 16, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Sanchez-Zapata, E.; Sayas-Barberá, E.; Sendra, E.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. Tomato and tomato byproducts. Human health benefits of lycopene and its application to meat products: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1032–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faustino, M.; Veiga, M.; Sousa, P.; Costa, E.; Silva, S.; Pintado, M. Agro-food byproducts as a new source of natural food additives. Molecules 2019, 24, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szabo, K.; Cătoi, A.-F.; Vodnar, D.C. Bioactive compounds extracted from tomato processing by-products as a source of valuable nutrients. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2018, 73, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, I.F.; Oreopoulou, V. Effect of extraction parameters on the carotenoid recovery from tomato waste. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, A.I.; Petron, M.J.; Delgado-Adamez, J.; Lopez, M.; Timon, M. Effect of Tomato Pomace Extracts on the Shelf-Life of Modified Atmosphere-Packaged Lamb Meat. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e13018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.M.; García, M.L.; Selgas, M.D. Dry fermented sausages enriched with lycopene from tomato peel. Meat Sci. 2008, 80, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candogan, K. The effect of tomato paste on some quality characteristics of beef patties during refrigerated storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2002, 215, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyiler, E.; Oztan, A. Production of frankfurters with tomato powder as a natural additive. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinela, J.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Bioactive compounds of tomatoes as health promoters. In Natural Bioactive Compounds from Fruits and Vegetables as Health Promoters Part II; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, UAE, 2016; pp. 48–91. [Google Scholar]

- Valdez-Morales, M.; Espinosa-Alonso, L.G.; Espinoza-Torres, L.C.; Delgado-Vargas, F.; Medina-Godoy, S. Phenolic content and antioxidant and antimutagenic activities in tomato peel, seeds, and byproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5281–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baiano, A.; Del Nobile, M.A. Antioxidant compounds from vegetable matrices: Biosynthesis, occurrence, and extraction systems. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 2053–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybylska, S. Lycopene—A bioactive carotenoid offering multiple health benefits: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, H.; Braun, C.L.; Ernst, H. The chemistry of novel xanthophyll carotenoids. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 101, S50–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Valverde, I.; Periago, M.J.; Provan, G.; Chesson, A. Phenolic compounds, lycopene and antioxidant activity in commercial varieties of tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowles, J.L.; Ranard, K.M.; Applegate, C.C.; Jeon, S.; An, R.; Erdman, J.W. Processed and raw tomato consumption and risk of prostate cancer: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018, 21, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Liu, R.; Dai, W.; Jie, Y.; Yu, G.; Fan, X.; Huang, Q. Lycopene attenuates early brain injury and inflammation following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 14316–14322. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, A.; Romero, A.; Mariscal-Arcas, M.; Monteagudo, C.; López, G.; Lorenzo, M.L.; Ocaña-Peinado, F.M.; Olea-Serrano, F. Association between dietary antioxidant quality score (DAQs) and bone mineral density in Spanish women. Nutr. Hosp. 2012, 27, 1886–1893. [Google Scholar]

- Baranska, M.; Schütze, W.; Schulz, H. Determination of lycopene and β-carotene content in tomato fruits and related products: Comparison of FT-Raman, ATR-IR, and NIR Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 8456–8461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulos, N.; Chiou, A.; Pyriochou, V.; Peristeraki, A.; Karathanos, V.T. Bioactive phytochemicals in industrial tomatoes and their processing byproducts. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Marisiddaiah, R.; Rubin, L.P. Inhibition of pulmonary ß-carotene 15, 15′-oxygenase expression by glucocorticoid involves PPARa. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćetković, G.; Savatović, S.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; Djilas, S.; Vulić, J.; Mandić, A.; Četojević-Simin, D. Valorisation of phenolic composition, antioxidant and cell growth activities of tomato waste. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, D.S.; Kozukue, N.; Kim, H.J.; Nishitani, Y.; Mizuno, M.; Levin, C.E.; Friedman, M. Protein, free amino acid, phenolic, β-carotene, and lycopene content, and antioxidative and cancer cell inhibitory effects of 12 greenhouse-grown commercial cherry tomato varieties. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014, 34, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, C.; Walia, S.; Nagal, S.; Walia, S.; Singh, J.; Singh, B.B.; Saha, S.; Singh, B.; Kalia, P.; Jaggi, S.; et al. Functional quality and antioxidant composition of selected tomato (Solanum lycopersicon L) cultivars grown in Northern India. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí, R.; Leiva-Brondo, M.; Lahoz, I.; Campillo, C.; Cebolla-Cornejo, J.; Roselló, S. Polyphenol and l-ascorbic acid content in tomato as influenced by high lycopene genotypes and organic farming at different environments. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toor, R.K.; Savage, G.P. Antioxidant activity in different fractions of tomatoes. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Huélamo, M.; Tulipani, S.; Estruch, R.; Escribano, E.; Illán, M.; Corella, D.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. The tomato sauce making process affects the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of tomato phenolics: A pharmacokinetic study. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, M.; Beekwilder, J.; Hall, R.D.; Sagdic, O.; Boyacioglu, D.; Capanoglu, E. Industrial processing versus home processing of tomato sauce: Effects on phenolics, flavonoids and in vitro bioaccessibility of antioxidants. Food Chem. 2017, 220, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgé, S.; Tourniaire, F.; Gautier, H.; Goupy, P.; Rock, E.; Caris-Veyrat, C. Changes in the contents of carotenoids, phenolic compounds and vitamin C during technical processing and lyophilisation of red and yellow tomatoes. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Sharma, A.; Singh, B.; Nagpal, A.K. Bioactivities of phytochemicals present in tomato. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 2833–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathunge, K.G.L.R.; Stratakos, A.C.; Delgado-Pando, G.; Koidis, A. Thermal and non-thermal processing technologies on intrinsic and extrinsic quality factors of tomato products: A review. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Conesa, D.; García-Alonso, J.; García-Valverde, V.; Iniesta, M.D.; Jacob, K.; Sánchez-Siles, L.M.; Ros, G.; Periago, M.J. Changes in bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity during homogenization and thermal processing of tomato puree. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2009, 10, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, F.E. Vitamin C: An Antioxidant Agent. In Vitamin C; InTech: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shariat, S.Z.A.S.; Mostafavi, S.A.; Khakpour, F. Antioxidant effects of vitamins C and E on the low-density lipoprotein oxidation mediated by myeloperoxidase. Iran. Biomed. J. 2013, 17, 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kocot, J.; Luchowska-Kocot, D.; Kiełczykowska, M.; Musik, I.; Kurzepa, J. Does Vitamin C influence neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disorders? Nutrients 2017, 9, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Azzi, A.; Stocker, A. Vitamin E: Non-antioxidant roles. Prog. Lipid Res. 2000, 39, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traber, M.G. Vitamin E. In Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease; Ross, C., Caballero, B., Cousins, R., Tucker, K., Ziegler, T., Eds.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2006; pp. 396–411. ISBN 9788416004096. [Google Scholar]

- Frusciante, L.; Carli, P.; Ercolano, M.R.; Pernice, R.; Di Matteo, A.; Fogliano, V.; Pellegrini, N. Antioxidant nutritional quality of tomato. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiola, A.; Rigano, M.M.; Calafiore, R.; Frusciante, L.; Barone, A. Enhancing the health-promoting effects of tomato fruit for biofortified food. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 139873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.C.; McNeil, A.K.; McNeil, P.L. Promotion of plasma membrane repair by vitamin E. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirsh, V.A.; Hayes, R.B.; Mayne, S.T.; Chatterjee, N.; Subar, A.F.; Dixon, L.B.; Albanes, D.; Andriole, G.L.; Urban, D.A.; Peters, U. Supplemental and dietary vitamin E, β-carotene, and vitamin C intakes and prostate cancer risk. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Kiyota, N.; Tsurushima, K.; Yoshitomi, M.; Horlad, H.; Ikeda, T.; Nohara, T.; Takeya, M.; Nagai, R. Tomatidine, a tomato sapogenol, ameliorates hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice by inhibiting acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyl-transferase (ACAT). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 2472–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manabe, H.; Murakami, Y.; El-Aasr, M.; Ikeda, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Ono, M.; Nohara, T. Content variations of the tomato saponin esculeoside A in various processed tomatoes. J. Nat. Med. 2011, 65, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.H.; Ahn, J.-B.; Kozukue, N.; Kim, H.-J.; Nishitani, Y.; Zhang, L.; Mizuno, M.; Levin, C.E.; Friedman, M. Structure–Activity Relationships of α-, β1-, γ-, and δ-Tomatine and Tomatidine against Human Breast (MDA-MB-231), Gastric (KATO-III), and Prostate (PC3) Cancer Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3891–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.R.; Kozukue, N.; Han, J.S.; Park, J.H.; Chang, E.Y.; Baek, E.J.; Chang, J.S.; Friedman, M. Glycoalkaloids and Metabolites Inhibit the Growth of Human Colon (HT29) and Liver (HepG2) Cancer Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2832–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Yahara, S.; Ikeda, T.; Ono, M.; Nohara, T. Cytotoxic major saponin from tomato fruits. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nohara, T.; Ono, M.; Ikeda, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; El-Aasr, M. The tomato saponin, esculeoside A. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 1734–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.R.; Kanda, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Manabe, H.; Nohara, T.; Yokomizo, K. Anti-hyaluronidase Activity in Vitro and Amelioration of Mouse Experimental Dermatitis by Tomato Saponin, Esculeoside A. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, E.M.; El-Kady, A.T.; El-Bialy, A.R. Charactrization of carotenoids (lyco-red) extracted from tomato peels and its uses as natural colorants and antioxidants of ice cream. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2014, 59, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vinha, A.F.; Alves, R.C.; Barreira, S.V.P.; Castro, A.; Costa, A.S.G.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Effect of peel and seed removal on the nutritional value and antioxidant activity of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) fruits. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, Z.; Wang, J.; Gao, R.; Ye, F.; Zhao, G. Sustainable valorisation of tomato pomace: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luisa García, M.; Calvo, M.M.; Dolores Selgas, M. Beef hamburgers enriched in lycopene using dry tomato peel as an ingredient. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eh, A.L.-S.; Teoh, S.-G. Novel modified ultrasonication technique for the extraction of lycopene from tomatoes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012, 19, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anarjan, N.; Jouyban, A. Preparation of lycopene nanodispersions from tomato processing waste: Effects of organic phase composition. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 103, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, H.; Faulks, R.; Granado, H.F.; Hirschberg, J.; Olmedilla, B.; Sandmann, G.; Southon, S.; Stahl, W. The potential for the improvement of carotenoid levels in foods and the likely systemic effects. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 880–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taungbodhitham, A.K.; Jones, G.P.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Briggs, D.R. Evaluation of extraction method for the analysis of carotenoids in fruits and vegetables. Food Chem. 1998, 63, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, I.F.; Oreopoulou, V. Process optimisation for recovery of carotenoids from tomato waste. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Wani, A.A.; Oberoi, D.P.S.; Sogi, D.S. Effect of extraction conditions on lycopene extractions from tomato processing waste skin using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones-Labarca, V.; Giovagnoli-Vicuña, C.; Cañas-Sarazúa, R. Optimization of extraction yield, flavonoids and lycopene from tomato pulp by high hydrostatic pressure-assisted extraction. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khawli, F.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Gullón, P.; Kousoulaki, K.; Ferrer, E.; Berrada, H.; Barba, F.J. Innovative green technologies of intensification for valorization of seafood and their by-products. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumcuoglu, S.; Yilmaz, T.; Tavman, S. Ultrasound assisted extraction of lycopene from tomato processing wastes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 4102–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yilmaz, T.; Kumcuoglu, S.; Tavman, S. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Lycopene and β-carotene from Tomato Processing Wastes. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2017, 29, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Luengo, E.; Condón-Abanto, S.; Condón, S.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Improving the extraction of carotenoids from tomato waste by application of ultrasound under pressure. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 136, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.H.Y.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Liceaga, A.M.; San Martín-González, M.F. Microwave-assisted extraction of lycopene in tomato peels: Effect of extraction conditions on all-trans and cis-isomer yields. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lianfu, Z.; Zelong, L. Optimization and comparison of ultrasound/microwave assisted extraction (UMAE) and ultrasonic assisted extraction (UAE) of lycopene from tomatoes. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008, 15, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, S.; Mikani, M. Lycopene green ultrasound-assisted extraction using edible oil accompany with response surface methodology (RSM) optimization performance: Application in tomato processing wastes. Microchem. J. 2019, 146, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konwarh, R.; Pramanik, S.; Kalita, D.; Mahanta, C.L.; Karak, N. Ultrasonication—A complementary ‘green chemistry’ tool to biocatalysis: A laboratory-scale study of lycopene extraction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012, 19, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, S.F.; Ekorong, F.J.A.A.; Karkal, S.S.; Cathrine, M.S.B.; Kudre, T.G. Green and innovative techniques for recovery of valuable compounds from seafood by-products and discards: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 85, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; Mendiola, J.A.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibáñez, E. Supercritical fluid extraction: Recent advances and applications. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 2495–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kehili, M.; Kammlott, M.; Choura, S.; Zammel, A.; Zetzl, C.; Smirnova, I.; Allouche, N.; Sayadi, S. Supercritical CO2 extraction and antioxidant activity of lycopene and β-carotene-enriched oleoresin from tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum L.) peels by-product of a Tunisian industry. Food Bioprod. Process. 2017, 102, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yi, C.; Xue, S.J.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, D. Effects of modifiers on the profile of lycopene extracted from tomato skins by supercritical CO2. J. Food Eng. 2009, 93, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vági, E.; Simándi, B.; Vásárhelyiné, K.P.; Daood, H.; Kéry, Á.; Doleschall, F.; Nagy, B. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of carotenoids, tocopherols and sitosterols from industrial tomato by-products. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2007, 40, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabio, E.; Lozano, M.; Montero de Espinosa, V.; Mendes, R.L.; Pereira, A.P.; Palavra, A.F.; Coelho, J.A. Lycopene and β-carotene extraction from tomato processing waste using supercritical CO2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 6641–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadoni, E.; Rita De Giorgi, M.; Medda, E.; Poma, G. Supercritical CO2 extraction of lycopene and β-carotene from ripe tomatoes. Dyes Pigments 2000, 44, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbonaviciene, D.; Viskelis, P. The cis-lycopene isomers composition in supercritical CO2 extracted tomato by-products. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 85, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Shi, J.; Xue, S.J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, D. Effects of supercritical fluid extraction parameters on lycopene yield and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 1088–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egydio, J.A.; Moraes, Â.M.; Rosa, P.T.V. Supercritical fluid extraction of lycopene from tomato juice and characterization of its antioxidation activity. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2010, 54, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, B.P.; Palavra, A.F.; Pessoa, F.L.P.; Mendes, R.L. Supercritical CO2 extraction of trans-lycopene from Portuguese tomato industrial waste. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasapollo, G.; Longo, L.; Rescio, L.; Ciurlia, L. Innovative supercritical CO2 extraction of lycopene from tomato in the presence of vegetable oil as co-solvent. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2004, 29, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzi, N.L.; Singh, R.K.; Vierling, R.A.; Watkins, B.A. Supercritical fluid extraction of lycopene from tomato processing byproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 2638–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, M.D.A.; Temelli, F.; Guigard, S.E.; Tomberli, B.; Gray, C.G. Apparent solubility of lycopene and β-carotene in supercritical CO2, CO2 + ethanol and CO2 + canola oil using dynamic extraction of tomatoes. J. Food Eng. 2010, 99, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollanketo, M.; Hartonen, K.; Riekkola, M.-L.; Holm, Y.; Hiltunen, R. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of lycopene in tomato skins. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 212, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurlia, L.; Bleve, M.; Rescio, L. Supercritical carbon dioxide co-extraction of tomatoes (Lycopersicum esculentum L.) and hazelnuts (Corylus avellana L.): A new procedure in obtaining a source of natural lycopene. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2009, 49, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Murakami, K.; Takemura, R.; Fukaya, T.; Wahyudiono; Kanda, H.; Goto, M. Thermal isomerization pre-treatment to improve lycopene extraction from tomato pulp. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 86, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Escalante, A.; Torrescano, G.; Djenane, D.; Beltrán, J.A.; Roncalés, P. Stabilisation of colour and odour of beef patties by using lycopene-rich tomato and peppers as a source of antioxidants. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2003, 83, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadkoohi, S.; Hoogenkamp, H.; Shamsi, K.; Farahnaky, A. Color, sensory and textural attributes of beef frankfurter, beef ham and meat-free sausage containing tomato pomace. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.-S.; Jin, S.-K.; Mandal, P.K.; Kang, S.-N. Quality of low-fat pork sausages with tomato powder as colour and functional additive during refrigerated storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bázan-Lugo, E.; García-Martínez, I.; Alfaro-Rodríguez, R.H.; Totosaus, A. Color compensation in nitrite-reduced meat batters incorporating paprika or tomato paste. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 1627–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Chin, K.B. Antioxidant activity of tomato powders as affected by water solubility and application to the pork sausages. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2013, 33, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Østerlie, M.; Lerfall, J. Lycopene from tomato products added minced meat: Effect on storage quality and colour. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.B.; Bragagnolo, N.; da Silva, M.G.; Skibsted, L.H.; Orlien, V. Antioxidant protection of high-pressure processed minced chicken meat by industrial tomato products. Food Bioprod. Process. 2012, 90, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Solvent | T (°C) | Time (min) | S/S Ratio 1 | Auxiliary Technique | Yield | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Hexane/acetone/ethanol (2:1:1) | 50 | 8 (×4) | 1:30 | - | 1.99 a | [69] |

| Skin + seeds | Hexane | 70 | 30 | 1:10 | - | 3.45 b | [16] |

| Acetone | 50 | 5.19 b | |||||

| Ethanol | 70 | 1.76 b | |||||

| Ethyl acetate | 4.62 b | ||||||

| Ethyl lactate | 24.3 b | ||||||

| Skin + seeds | Ethanol | 25 | 30 | 1:10 | - | 0.61 b | [68] |

| Hexane | 2.52 b | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate | 3.15 b | ||||||

| Acetone | 3.34 b | ||||||

| Hexane/ethanol (50:50) | 2.81 b | ||||||

| Hexane/acetone (50:50) | 3.05 b | ||||||

| Hexane/ethyl acetate (50:50) | 3.65 b | ||||||

| Hexane/ethyl acetate (45:55) | 1:9 | 3.75 b | |||||

| Pulp | Hexane/ethanol/acetone (60:20:20) | - | 24 h | 1:2 | - | 0.36 a | [70] |

| 20 | 10 | HHPE (450 MPa) | 2.01 a | ||||

| Skin + seeds | Hexane/acetone/ethanol (2:1:1) | 60 | 40 | 1:50 | - | 9.39 a | [72] |

| 5 | 30 | 1:35 | UAE (90W) | 8.99 a | |||

| Skin + seeds | Hexane/acetone/ethanol (2:1:1) | 15 | 30 | 1:35 | - | 5.72 a | [73] |

| UAE (90W) | 7.69 a | ||||||

| Skin + seeds + pulp | Hexane/ethanol (50:50) | 45 | 6 | 1:33 | UUP Manosonication (50kPa/US amplitude 94 µm) | 14.08 b | [74] |

| Peel | Ethyl acetate | - | 1 | 1:20 | MAE (400W) | 13.87 a | [75] |

| Skin + seeds + pulp | Ethyl acetate | 86.4 | 29.1 | 1:8 | UAE (50W) | 89.4% c | [76] |

| - | 6.1 | 1:10.6 | UMAE (98W) | 97.4% c | |||

| Skin + pulp | Sunflower oil | - | 10 | 1:5 | UAE | 91.5 a | [77] |

| Hexane | 60 | - | 63.7 a | ||||

| Hexane/acetone/methanol (2:1:1) | - | 74.9 a |

| Material | Pressure (MPa) | T (°C) | Time (min) | Flow | Particle Size (mm) | Modifier/Co-Solvent | Yield | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato juice | 35 | 80 | 180 | 1.7 g/min | - | - | 76.9% a | [88] |

| Skin + seeds | 30 | 60 | - | 0.59 g/min | 0.36 | - | - | [89] |

| Skin + seeds | 34.5 | 86 | 20 | 2.5 mL/min | - | - | 61% a | [91] |

| Skin + seeds | 40 | 70 | 90 | 2 mL/min | 1 | - | 19.21 b | [87] |

| Skin | 41 | 80 | 105 | 4 g/min | 0.3 | - | 72.8 c | [81] |

| Skin + seeds | 30 | 80 | - | 13.2 g/min | 0.345 | - | 80% a | [84] |

| Skin + seeds | 46 | 80 | 22.7 | 2 mL/min | - | - | 90.1% a | [83] |

| Tomato juice + pulp | 53.7 | 73.9 | 155 | - | <0.2 | - | 25.12 d | [86] |

| Skin + pulp | 27.6 | 80 | 30 | 500 cm3/min | - | - | 64.41 c | [85] |

| Whole tomato | 40 | 40 | 360 | 0.5 L/min | 0.5–1 | - | 0.14 e | [92] |

| Ethanol * | 0.23 e | |||||||

| Canola oil * | 0.57 e | |||||||

| Whole tomato | 40–45 | 60–70 | 240 | 10 kg/h | - | Hazelnut powder + | 72% a | [94] |

| Skin | 35 | 75 | - | 3.5 L/min | - | Ethanol (10%) olive oil (10%) + | 73.3 b | [82] |

| Meat Product | Material | Amount | Main Effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patties & burgers | Tomato Oleoresin | 0.55 g/kg | ↓ Lipid oxidation & discolouration; ↑ Redness | [96] |

| 2 g/kg | ||||

| Tomato Powder | 15 g/kg | No effects | ||

| 50 g/kg | ↓ Lipid oxidation & discolouration; ↑ Redness | |||

| Tomato Paste | 5, 10 & 15% | ↓ Lipid oxidation & discolouration; ↑ Redness; = Sensory colour scores | [19] | |

| Tomato Powder | 1.5, 3, 4.5 & 6% | ↓ Discolouration; ↑ Redness; ↓ Sensory scores | [63] | |

| 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 & 1% | ↓ Lipid oxidation & discolouration; ↑ Redness; ↑ Sensory properties | [11] | ||

| Aqueous Extract | 1 g/kg | No effects | [5] | |

| Frankfurter and cooked sausages | Tomato Powder | 1 & 2% | ↓ Lipid oxidation; ↑ Redness | [100] |

| 2 & 4% | ↑ Lipid oxidation; ↑ Redness; ↑ Sensory properties | [20] | ||

| 0.8, 1.2 & 1.5% | ↓ Lipid oxidation; ↑ Redness; ↑ Sensory properties | [98] | ||

| 1, 3, 5 & 7% | ↑ Redness; ↑ Sensory properties | [97] | ||

| Tomato Paste | 2.5 & 3% | ↓ Lipid oxidation; ↑ Redness; ↑ Sensory colour scores | [99] | |

| 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 & 16% | ↑ Lipid oxidation; ↑ Redness; ↑ Sensory colour scores | [2] | ||

| Dry-fermented sausage | Tomato Powder | 6, 9 & 12 g/kg | ↑ Redness; = Sensory properties | [18] |

| Minced meat | Tomato and tomato waste | 0.1-0.3% | ↓ Lipid oxidation; = Redness | [102] |

| Tomato Powder, Paste and crystalline lycopene | - | ↓ Lipid oxidation & discolouration; ↑ Redness | [101] | |

| Luncheon roll | Tomato Powder | 1.5 & 3% | ↑ Lipid oxidation; ↑ Redness; ↓ Sensory properties | [10] |

| Mortadella | Tomato Paste | 2, 6 & 10% | ↓ Lipid oxidation; ↑ Redness; ↑ Sensory properties | [9] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Domínguez, R.; Gullón, P.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. Tomato as Potential Source of Natural Additives for Meat Industry. A Review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9010073

Domínguez R, Gullón P, Pateiro M, Munekata PES, Zhang W, Lorenzo JM. Tomato as Potential Source of Natural Additives for Meat Industry. A Review. Antioxidants. 2020; 9(1):73. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9010073

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomínguez, Rubén, Patricia Gullón, Mirian Pateiro, Paulo E. S. Munekata, Wangang Zhang, and José Manuel Lorenzo. 2020. "Tomato as Potential Source of Natural Additives for Meat Industry. A Review" Antioxidants 9, no. 1: 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9010073

APA StyleDomínguez, R., Gullón, P., Pateiro, M., Munekata, P. E. S., Zhang, W., & Lorenzo, J. M. (2020). Tomato as Potential Source of Natural Additives for Meat Industry. A Review. Antioxidants, 9(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9010073