Abstract

An imbalance in the production of reactive oxygen species in the body can cause an increase of oxidative stress that leads to oxidative damage to cells and tissues, which culminates in the development or aggravation of some chronic diseases, such as inflammation, diabetes mellitus, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. Secondary metabolites from Inula species can play an important role in the prevention and treatment of the oxidative stress-related diseases mentioned above. The databases Scopus, PubMed, and Web of Science and the combining terms Inula, antioxidant and secondary metabolites were used in the research for this review. More than 120 articles are reviewed, highlighting the most active compounds with special emphasis on the elucidation of their antioxidative-stress mechanism of action, which increases the knowledge about their potential in the fight against inflammation, cancer, neurodegeneration, and diabetes. Alantolactone is the most polyvalent compound, reporting interesting EC50 values for several bioactivities, while 1-O-acetylbritannilactone can be pointed out as a promising lead compound for the development of analogues with interesting properties. The Inula genus is a good bet as source of structurally diverse compounds with antioxidant activity that can act via different mechanisms to fight several oxidative stress-related human diseases, being useful for development of new drugs.

1. Introduction

Oxygen metabolism, which involves mainly redox reactions, is fundamental for human life, but it leads to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [1,2], affecting regulation of several biological processes and cell functions [3]. ROS and RNS include not only radical species such as hydroxyl radical (●OH), superoxide radical anion (O2●−), and nitric oxide radical (●NO), having unpaired electrons and exhibiting short biological half-lives, but also labile nonradicals species like singlet oxygen (1O2), peroxynitrite (ONOO−), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which can also be transformed into some of the radical species mentioned above [4,5]. All these species, due their irreversible and nonselective reactivity, are associated with oxidative-stress related damage [4]. In fact, when cellular production of ROS and RNS overwhelms the antioxidant capacity of cells, it leads to a state of oxidative stress, which in turn can cause oxidative damage to large biomolecules such as proteins, lipids, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) [6]. The consequent degradation of cellular integrity and tissue functions culminates in the development or aggravation of some disorders such as inflammation, ageing, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative disease, and obesity [6,7,8,9].

A recent topic of increasing interest and investigation in the scientific community is the use of plants and their secondary metabolites as therapeutic agents [10,11,12,13]. Plants are an excellent source of compounds with pharmacological potential and/or possessing leading chemical structures in the development of new drugs [10,11,12], and they have always been used effectively as medicine for treatment of human diseases. The Inula species (more than 100 species [14]) from the Asteraceae family (also known as Compositae) are widely distributed in Africa, Asia, and Europe and have been reported to possess more than 400 compounds, mainly terpenoids (sesquiterpene lactones and dimers, diterpenes, and triterpenoids) and flavonoids, with many of them exhibiting interesting pharmacological activities [12,13], and are of great scientific and medicinal interest, as evidenced by the two ongoing clinical studies involving herbal preparations containing Inula species (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03256708 and NCT02918487). Furthermore, many studies continue to be published showing the potential of Inula species in the treatment and prevention of diseases related to oxidative stress, showing traditional medicine applications of plant, in vitro, and in vivo biological activities of Inula extracts. In the Kashmir Himalayas, the roots and seeds of Inula racemosa Hook. f. are used to treat various health conditions including inflammation and rheumatism [15], while in Pakistan, to treat rheumatism, they use Inula orientalis Lam. (syn. Inula grandiflora Willd) [16]. The ethanol extract of Inula helenium L. exhibits antioxidant and anti-neuroinflammatory activities in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated BV-2 microglia cells, suggesting that the extract could act by inhibiting NO production and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression levels through suppression of the expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels [17]. Qun et al. [18] revealed that the hydroethanolic extract of Inula helenium presented anti-inflammatory activity in a mouse model, acting by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-induced activation of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and the expression of IL-1, IL-4 and TNF-α, as shown by the test in human keratinocyte HaCat cell line. Another study [19], revealed that ethanol extract from flowers of Inula japonica Thunb. inhibited lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes in vitro and reported also that C57BL/6J mice models fed with high-fat diet with 2.5 g of the extract showed a decrease in body fat mass, hepatic lipid accumulation, and body weight gain, while increasing muscle weight.

The taxonomy of some Inula species, as in many other genera, has been altered in recent years, and in this review, only the published works involving species whose binominal Latin name is considered by the “The Plant List” database [14] as an Inula accepted name are considered. The abovementioned studies are only a few examples of the great interest in Inula anti oxidative-stress related disorders research, which led to an increase in the investigation of the metabolites responsible for the activities exhibited, providing support for Inula’s use in traditional medicine, as well as establishing the Inula genus as a source of antioxidant compounds. This paper intends to provide a critical bibliographic review that demonstrates this, showing a selection of Inula compounds with the highest pharmacological potential for the treatment of oxidative-stress related pathological problems as well as to discuss the mechanisms of action involved in their pharmacological action.

2. Radical Scavenging Activity of Secondary Metabolites from Inula Species Determined Using DPPH and ABTS Methods

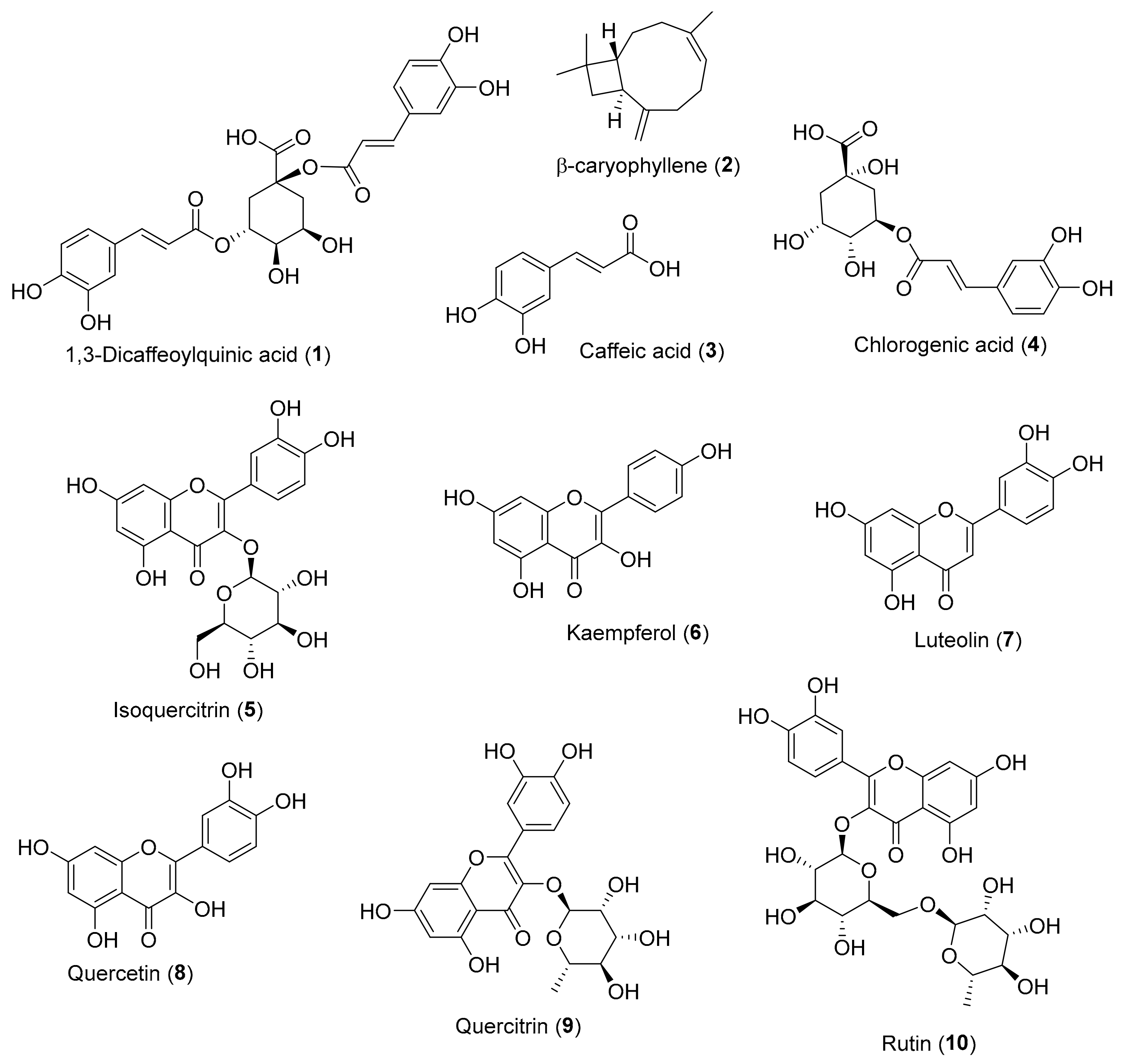

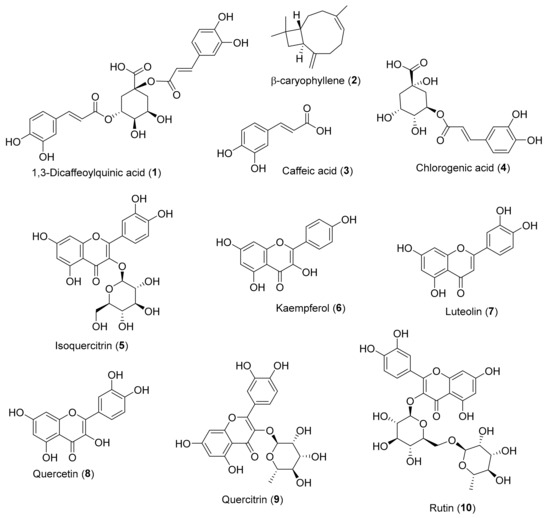

There are many methods available to allow a first approach for evaluating the antioxidant potential of a compound or extract [20]. Among them, the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS) free radical scavenging colorimetric methods are the most popular, since they offer advantages of being rapid, simple, and inexpensive and provide first-hand information on the overall antioxidant capacity of the tested sample [21,22]. However, the two methods are not equivalent: The DPPH scavenging test measures the ability of a compound to neutralize the DPPH radical by a mechanism involving single-electron transfer (SET), while in ABTS assay, the radical neutralization mechanism is mainly hydrogen-atom transfer (HAT), although in some cases, it could also be electron transfer, resulting in a more sensitive method [23,24]. As already mentioned, more than 400 secondary metabolites isolated from Inula species are known, and many of them exhibit radical scavenging properties by DPPH and/or ABTS methods. A critical non-exhaustive selection of the most representative Inula secondary metabolites, which exhibit an activity identical or superior to that of a reference compound, are presented in Table 1, and the respective chemical structures are shown in Figure 1. In addition, in this selection, we preferentially consider the published works in which the authors present an associated statistical parameter, thus guaranteeing the reliability of the result, and a low associated error (c.a. 10% of the mean).

Table 1.

Scavenging effects of Inula secondary metabolites 1–10 and reference compound on 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS) radicals (EC50, μM).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of Inula secondary metabolites (1–10) with DPPH and/or ABTS antioxidant activity.

In some assigned cases (see Table 1 note), there was the necessity to convert the EC50 values from the original bibliographic source from μg/mL to μM, to allow a comparison of antioxidant activity between the compounds.

According to the DPPH assay values in Table 1, β-caryophyllene (2), with an EC50 of 1.25 ± 0.06 μM, is by far the most active compound, followed by quercetin (8) and quercitrin (9), also with interesting EC50 values (EC50 < 10 μM). It should be noticed that all these compounds showed better EC50 values than the reference compound used in their studies, i.e., ascorbic acid or trolox.

As it is possible to see in Table 1, regarding the ABTS assay, a lot fewer published results are available in the literature. Quercetin (8) and caffeic acid (3) are the compounds with the lowest EC50 values, i.e., 6.25 ± 1.09 μM and 8.82 ± 0.33 μM, respectively. Both compounds presented better radical scavenging activity than the reference compound ascorbic acid.

The higher sensitivity of the ABTS method is reflected in lower EC50 values when compared to those obtained by the DPPH method for the same compound tested.

It should be emphasized that the results of DPPH and ABTS are somewhat dependent on the used experimental conditions, and therefore, different works may report different DPPH and ABTS EC50 values for the same compound (see example: Kaempferol (6), Table 1). To mitigate this, it is very important to present the EC50 value of an appropriate reference, thus allowing a more reliable comparison of the level of activity in the different publications. Surprisingly, even in recent publications, a significant number of published papers continue to be found that do not meet this requirement. This is a point at which researchers and the peer review process should be more demanding and rigorous, contributing greatly to making the published data more comparable and therefore more useful and of greater impact.

The data in Table 1 show that Inula species have relevant compounds with great antioxidant activity, many of them more active than some of the reference compounds, such as ascorbic acid, already used by industry as antioxidants.

Although the antioxidant activity assays by the DPPH and ABTS methods are simple, rapid, and very useful as a first approach, the extrapolation of their results to the antioxidant effect at a cellular level in a biological environment is impossible, and they do not give any information about the cellular mechanisms in which the compounds tested act. This information is very relevant and is obtained using methods and approaches very different from those discussed so far.

3. Secondary Metabolites from Inula Species against Oxidative-Stress Related Diseases

As noted above, compounds isolated from Inula species exhibit a wide range of biological activities against oxidative stress diseases such as inflammation, diabetes, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, much research has been developed to understand how Inula compounds act, using models more complex than the model of radical scavenging referred in point 2, and therefore closer to real biological systems. In this section, we present not an exhaustive compilation but rather a critical analysis of the more in-depth studies and the most relevant aspects of the action mechanisms exhibited by the Inula compounds that have, as a final consequence, the reduction of the oxidative stress nature inherent to the mentioned diseases.

3.1. Inflammation

Since overproduction of ROS leads to cellular and tissue damage, inflammation is intrinsically linked to oxidative stress [42]. Inflammation is a complex defense mechanism that is vital to health since it is the immune system’s response to harmful stimuli, such as damaged cells, toxic compounds, pathogens or irradiation [43]. Cellular and molecular events are triggered in an acute inflammatory response in order to mitigate the impact of an injury or infection, allowing restoration of tissue homeostasis [44]. However, uncontrolled acute inflammation may become chronic, leading to the development of a variety of chronic inflammatory diseases [45]. Intracellular inflammatory signaling pathways include NF-κB, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK/STAT3) pathways. All of them are activated by inflammatory stimuli such as TNF-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and IL-6 that interact with the Toll-like receptors (TLR), TNF receptor (TNFR), IL-1 receptor (IL-1R), and IL-6 receptor (IL-6R), mediating inflammation through the production of more inflammatory stimuli [46]. NO is also fundamental in the cellular defense mechanism of inflammation, since NO synthase is induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines; however, it can cause adverse effects such as autoimmune reactions and neurodegenerative syndromes when overproduction of NOs occurs [47]. Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) is a prostaglandin–endoperoxide synthase 2 enzyme that is responsible for generation of prostanoids like prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) that act in the modulation of multiple inflammation and pro-carcinogenic processes [48,49]. The overexpression of COX-2 has been associated with carcinogenesis, resistance to apoptosis, and inflammatory diseases [50,51]. COX-2 expression is controlled by the binding of many trans-factors to the corresponding sites on its promoters, like NF- κB, which in turn, depends on the degradation of IκB proteins by an IκB kinase (IKK) complex [52].

Direct myocardial injury can be caused by inflammatory cytokines response, microcirculation dysfunction, and insufficient energy [53]. The work of Huang et al. [54] clarifies the mechanism by which isoquercitrin (5) (Figure 1) attenuates the inflammatory response on LPS-induced cardiac dysfunction on C57BL/6 mice or H9c2 cardiomyoblasts. After LPS stimulation, production of large amounts of TNF-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1), and IL6 (all pro-inflammatory cytokines) starts, regulated via the NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to cardiac injury. According to this study, pretreatment with isoquercitrin (5) (40 μM) attenuates LPS-induced cardiac dysfunction as well as decreases the levels of TNF-α, IL6, MCP1, and iNOS in vivo and in vitro by blocking the MAPK and NF-κB pathways.

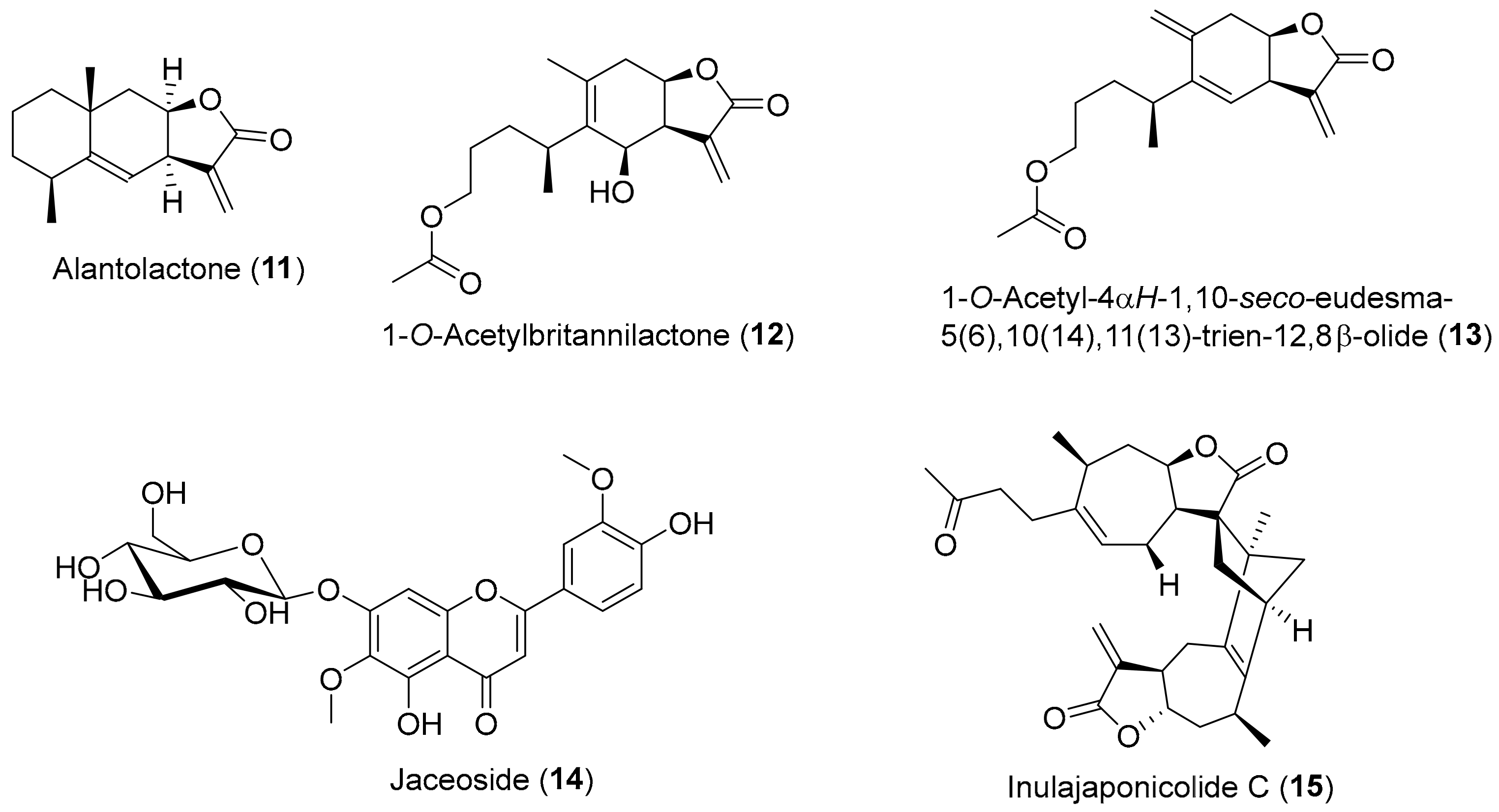

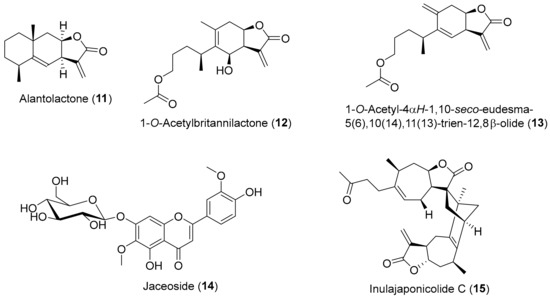

Alantolactone (11) (Figure 2) is a eudesmanolide sesquiterpene lactone with an α-methylene–γ-lactone moiety that is considered the active principle of Inula helenium [55]. Alantolactone (11) is found in several Inula species besides Inula helenium, e.g., Inula japonica, Inula racemosa, Inula royleana DC., and Inula falconeri Hook.f. [12]. Zhang et al. [56] showed that alantolactone (11) inhibits LPS-induced NO production in RAW 264.7 macrophages, presenting an IC50 value of 7.39 ± 0.36 μM, being better than the positive control aminoguanidine (IC50 = 9.12 ± 0.35 μM). These results are in accordance with the ones presented by Chun et al. [57], where compound 11 at 10 μM inhibited the production of NO, PGE2, and TNF-α, as well as COX-2 and iNOS protein and mRNA transcription in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. The same study showed that alantolactone (11) disrupted the NF-κB signaling pathway through inhibition of the phosphorylation of inhibitory κB-α (IκB-α) and IKK, as well as the MAPK pathway. A recent study [18] with HaCat cell line revealed that alantolactone (11) presented anti-inflammatory activity, since it also could inhibit the expression of IL-1, IL-4, and TNF-α and TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB, in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of Inula secondary metabolites (11, 12, 14, 15) and the semisynthetic derivative (13) with reported activity against oxidative-stress inflammatory process.

1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) (Figure 2) is a 1,10-seco-eudesmanolide sesquiterpene that, like compound 11, has an α-methylene–γ-lactone skeleton, found in Inula britannica var. chinensis and Inula japonica [12], and that possesses cytotoxic potential [58,59] and anti-inflammatory properties [60,61]. A recent study by Wei et al. [62], found that the 6-deoxy1-O-acetylbritannilactone with a methylene at C-14 position, an analogue of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) labelled as 1-O-acetyl-4αH-1,10-seco-eudesma-5(6),10(14),11(13)-trien-12,8β-olide (13) (Figure 2), exhibits an anti-inflammatory effect. In fact, compound 13 decreased NO production and iNOS expression in RAW 264.7 macrophage normal cell line with IC50 value of 1.3 μM.

Several compounds from Inula montana L. possessed promising anti-inflammatory activity through inhibition of NO production in murine macrophages RAW 264.7 cell line, jaceoside (14) (Figure 2) being the compound most active with IC50 of 0.34 ± 0.01 μM, being several times better than the positive control drug dexamethasone (IC50 of 3.89 ± 0.94 μM) [63].

Several dimeric- and trimeric-sesquiterpenes isolated from Inula japonica exhibit anti-inflammatory properties [64]. One of them, the 2,4-linked sesquiterpene lactone dimer named inulajaponicolide C (15) (Figure 2), presented the most potent inhibitory effect over NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells with IC50 value of 1.0 ± 0.1 μM, being much better than the indomethacin (IC50 = 14.6 ± 0.5 μM) used as positive control.

3.2. Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia resulting from flaws in insulin action, insulin secretion, or both [65]. Hyperglycemia induces the increase of ROS production, which in turns causes damages in cells and activation of inflammation processes [66] and triggers apoptosis in the β-cells, worsening the lack of insulin [67]. Thus, acquired insulin resistance and glucose intolerance are associated with chronic inflammation [68,69], the pro-inflammatory cytokine being IL-6 the main link between both processes [70].

A randomized double-blind clinical trial placebo-controlled performed in 30 patients suffering from impaired glucose tolerance showed that the administration of 400 mg of chlorogenic acid (4) (Figure 1) three times a day for 12 weeks decreased fasting plasma glucose and increased insulin sensitivity, despite the fact that insulin secretion decreased [71]. The authors suggest that the antidiabetic effect of chlorogenic acid (4) could be due to its action on hepatic peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor α (PPARα), which plays a role as a facilitator in clearing lipids from the liver and enhancing insulin sensitivity [72].

The most significant component of the regulating post-prandial insulin secretion mechanism is glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) that is secreted from cells in the gastrointestinal tract in response to nutrient absorption [73]. GLP-1 is rapidly inactivated in vivo by circulating dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-IV) [74]. A recent study [75], using colorectal adenocarcinoma NCI-H716 cells as an in vitro model of gastrointestinal cells, showed that isoquercitrin (5) is a promising compound to treat type 2 diabetes since it was identified as a DPP-IV inhibitor, with an IC50 of 96.8 μM. Furthermore, the levels of GLP-1 increased, suggesting that isoquercitrin (5) may also stimulate GLP-1 secretion and bioavailability in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, the same work [75] using in vivo assays with type 2 diabetic Chinese Kunming mice showed that isoquercitrin (5) treatment for 8 weeks (80 mg/kg b.w. per day), significantly increased GLP-1 and insulin levels in plasma while lowering the fasting blood glucose levels. These results are in accordance with the ones obtained by Huang et al. [76] that reported hepatoprotective potential of isoquercitrin (5) (10 and 30 mg/kg b.w. per day) against type 2 diabetes-induced hepatic injury in rats after 21 days of treatment with significant suppression of DPP-IV mRNA level expression.

Kim et al. [77] demonstrated that alantolactone (11) (Figure 2) could increase glucose uptake levels, suggesting it as a great candidate for the treatment of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. In fact, the 4 h pretreatment of L6 rat myoblast cell line with alantolactone (11) (at 0.5 μM), followed by 24 h exposure to IL-6, caused a decrease in the IL-6 induced insulin resistance and allowed the increase of glucose uptake levels to the levels of the control group (without exposure to IL-6). Therefore, alantolactone (11) possess antidiabetic potential resulting from its effect against IL-6 induced inflammatory process.

3.3. Neurological Damages

Formation and deposition of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques in the brain in excess, a characteristic of Alzheimer disease (AD), can generate oxidative stress, which triggers inflammatory processes and exacerbates the destruction of hippocampal and neighboring tissues [78]. Therefore, in order to ameliorate or prevent the progression of ROS-mediated neurological damages, antioxidants are considered as promising candidates for therapeutics not only in AD but also in other neurodegenerative diseases like Huntington or Parkinson’s [79,80].

There are indications in the literature that alantolactone (11) (Figure 2) exhibits relevant properties to combat oxidative stress, not only in inflammatory processes, as noted above, but also in neurological system. In fact, Seo et al. [81] showed that alantolactone (11) at 0.1 to 1 μM has neuroprotective effects on mouse cortical neurons since cell viability was little affected by exposure to Aβ25–35 (10 μM), preventing also the shortening of dendrite length, in contrast to what happened in the control group exposed only to Aβ25–35 (10 μM). In addition, alantolactone (11) treatment decreased acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity and decreased intracellular ROS production in a dose-dependent manner [81]. However, the authors alert that alantolactone (11) at high doses (i.e., >5 μM) could act as prooxidant promoting ROS production. Moreover, the administration of alantolactone (11) (1 mg/kg b.w.) reverts scopolamine-induced cognitive impairments in male C57BL/6J and C57BL/6J/Nrf2 knockout mouse, indicating that alantolactone (11) improves working memory, probably mediated by activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway [81], a factor that modulates the antioxidant response to an oxidant exposure by a increasing the expression of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes, like the glutathione reductase (GSR), γ-glutamylcysteine ligase (GCL), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1) [82,83].

Oxidative stress following traumatic brain injury (TBI) can have devastating effects on brain tissues, since it causes oxidase enzymes activation, mitochondrial functions become impaired, membrane phospholipids are destroyed, and several cellular components, such as DNAs, RNA, carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, are harmed, which ultimately leads to irreversible damage to neuronal cells and brain tissue [84]. A very recent study [85] reported that treatment of TBI in male Sprague–Dawley rats with alantolactone (11) (Figure 2) at 10 and 20 mg/kg b.w. alleviated cerebral edema and improved neurological function via anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidative pathways. Furthermore, the same study [85] reported that alantolactone (11) significantly suppressed COX-2 expression by inhibiting the activation of the NF-κB pathway, diminishing the levels of glutathione disulphide (GSSG) and malondialdehyde (MDA) (products of lipid peroxidation and an important marker of oxidative damage level [86]) while causing in brain tissues after TBI an increase in the level of glutathione (GSH) and in the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), the antioxidant first line defense [87].

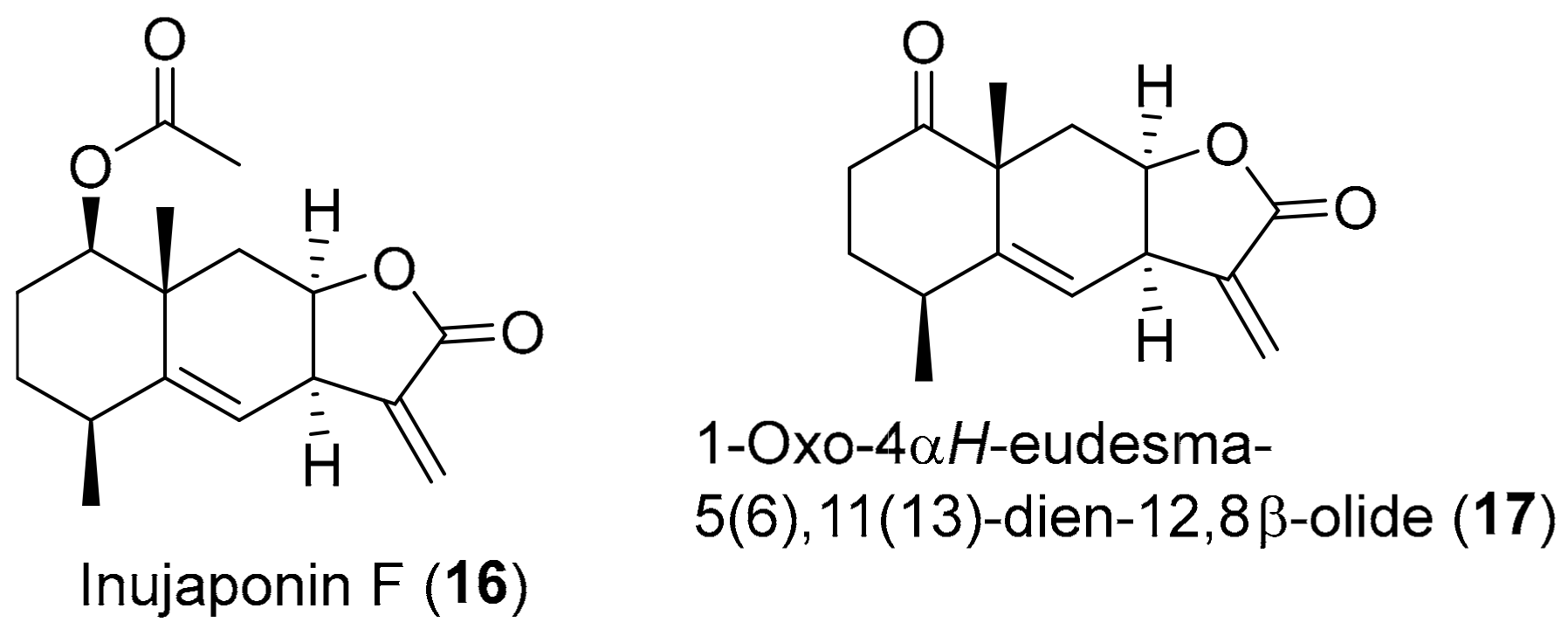

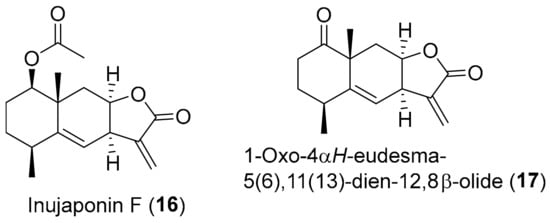

Neurodegenerative diseases like AD are closely related with neuroinflammation [88]. In fact, excessive amount of NO accumulates in the central nervous system (CNS) as a result of inflammatory response over damaged microglia cells, which in turns exacerbates neuroinflammation and aggravates neurodegenerative diseases [89]. Liu et al. [90] isolated various compounds from Inula japonica, in an attempt to find potentially useful compounds with NO inhibitory effects for the treatment of neuroinflammation. Inujaponin F (16) (Figure 3) and 1-oxo-4αH-eudesma-5(6),11(13)-dien-12,8β-olide (17) (Figure 3) presented higher NO inhibitory activity in LPS-induced murine microglial BV-2 cells with IC50 values of 1.3 ± 0.1 μM and 1.5 ± 0.2 μM, respectively, higher activity than the one reported by the positive control 2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea sulphate (SMT) that presented an IC50 value of 2.9 ± 0.5 μM [90]. This anti-neuroinflammatory effect of compounds 16 and 17, according to the molecular docking studies, could be due to their ability to interact with residues of the active cavities of iNOS protein, blocking it [90]. The iNOS protein is the most critical component in charge of the amount of NO in inflammatory response [91].

Figure 3.

Chemical structure of Inula secondary metabolites (16 and 17) with reported activity against neurological oxidative-stress damages.

3.4. Carcinogenesis

Carcinogenesis is a complex process through which cancer develops, but putting it simple, it basically involves genetic modification of genomic DNA (creation of a mutated cell) followed by growth and division of the aberrant cell with accumulation of additional genetic and epigenetic changes [92]. A recurrent characteristic of cancer progression and resistance to treatment is deregulated redox signaling, which means alteration in redox balance and culminates in elevated levels of ROS [93]. ROS production causes more DNA damage and triggers signaling pathways that activate pro-carcinogenic factors and anti-apoptotic responses, favoring cancer survival and progression [94,95].

Dahham et al. [27] found that β-caryophyllene (2) (Figure 1) demonstrated a selective anti-proliferative effect against colon cancer HCT 116 cells (IC50 = 19 μM,) and pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells (IC50 = 27 μM), with selectivity index (SI) values from 5.8 to 27.9. It should be pointed out that β-caryophyllene (2) presented IC50 values not too far from the positive controls 5-fluorouracil (IC50 = 12.7 μM) and betulinic acid (IC50 = 19.4 μM, SI = 2.7-5). Additionally, β-caryophyllene (2) demonstrated apoptotic properties in the HCT 116 cells, by caspase-3 enzyme activation, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, and DNA fragmentation pathways [27].

An interesting in vitro and in vivo study [96] investigated the effects of alantolactone (11) (Figure 2) on several glioblastoma multiforme cells (GBM) (i.e., U87, U251, U118, and SH-SY5Y cell lines) and determined that it suppresses the growth of GBM cells. According to the results, alantolactone (11) reduced in a dose- and time-dependent manner the survival rate of the tested cell lines exhibiting the highest cytotoxic activity against U251 cell line (IC50 = 16.33 ± 1.93 μM), without displaying cytotoxicity against normal human glial cell line, SVG, at concentrations below 25 μM. Furthermore, against U251 and U87 cell lines, alantolactone (11) reported IC50 values significantly lower than those of celecoxib (CB), a classical and potent commercial COX-2 inhibitor, which reported IC50 values of 120.32 μM and 135.27 μM, respectively [96]. In addition, this study [96] also found that the antitumor effect of alantolactone (11) in the GBM cells could be in part via NF-κB/COX-2-mediated signaling cascades through inhibition of IKKβ kinase activity. As referred above, the overexpression of COX-2 has been associated with inflammatory processes and also related with carcinogenesis and resistance to apoptosis [50,51]. Since IKKβ is the major subunit of this complex, its inhibition by alantolactone (11) ultimately leads to a decrease in the COX-2 expression and consequent intensification of the cytotoxic effect in the cells. Taking into account the results of the in vitro studies, the authors [96] also investigated the possible therapeutic effect of alantolactone (11) against tumor growth in BALB/c male nude mice. They noticed that toxic effects were not detected in the mice treated only with alantolactone (11) (10 and 20 mg/kg b.w.), and tumor weights and volumes decreased in the study group when compared with the control group (tumor inhibition rates of 47.73 ± 9.32% and 70.45 ± 13.33%, respectively).

Alantolactone (11) seems to be a very versatile compound. Not only due to its activities referred to in the previous points, but also because it exhibits cytotoxic activity against solid tumors, as referred to in the previous paragraph, and also against nonsolid tumors, as shown by Ding et al. [97]. In this work [97], alantolactone (11) shows selective (SI > 8) antitumor activity against several acute myeloid leukemia stem cell lines (AML), such as THP-1 (IC50 = 2.17 ± 0.72 μM), KG1a (IC50 = 2.75 ± 0.65 μM), K562 (IC50 = 2.75 ± 0.64 μM), and HL60 (IC50 = 3.26 ± 0.88 μM), as well as in the multidrug-resistant cell lines K562/A02 (IC50 = 2.73 ± 0.83 μM) and HL60/ADR (IC50 = 3.28 ± 0.80 μM), where alantolactone (11) is more cytotoxic than the clinically used drug adriamycin (ADR) (IC50 = 8.94 ± 3.79 μM against K562/A02 and IC50 = 5.54 ± 1.21 μM against HL60/ADR). Unfortunately, the results of this work should be considered under reserve, since the associated standard deviation is very high (about 20% of the mean). Above all, this applies to the cytotoxicity of the clinical drug against the K562/A02 multiresistant cell line, where the standard deviation reaches 42% of the mean value, which means a high dispersion of the results obtained in different replicates and, therefore, a low confidence in the result. The authors [97] also noticed that treatment with alantolactone (11) on HL60 and KG1a cell lines caused induction of cellular apoptosis by suppression of the NF-κB pathway, an important pathway involved in oxidative-stress related complications. An overexpression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax was observed, while the expression of Bcl-2, an apoptosis inhibitor, and of NF-κB p65 subunit were reduced significantly. The alantolactone also caused the reduction of the downstream target proteins of the NF-κB pathway, the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) and the FLICE-inhibitory protein (FLIP) that play important roles in cell apoptosis [97].

1-O-Acetylbritannilactone (12) (Figure 2), like alantolactone (11) (Figure 2), is a sesquiterpene lactone very common in Inula species [12] that elicits apoptosis in cancer cell lines through partially targeting the NF-κB pathway [98]. In fact, Wang et al. [98] showed that the combination of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) (10 μM) and the approved chemotherapy drug gemcitabine (10 μg/mL) had a synergistic effect on the suppression of A549 cells proliferation, by inducing apoptosis in a 72 h treatment. The mixture decreases significantly the cell survival rates (mix of the two compounds cell survival = 30.2%) when compared with the control (100%), and with the compounds alone (1-O-acetylbritannilactone = 59.1%; gemcitabine alone = 49.7%). The authors also found that 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) and the combination treatment significantly decreased the expression of NF-κB and Bcl-2, while upregulating Bax expression [98].

Angiogenesis is a complex and normal process that allows the formation of new blood vessels (capillary formation) from the pre-existing ones, being crucial during wound healing or embryo development; however, it is abnormally present in cancer [99]. As a critical component of tumor angiogenesis, glycoprotein vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is widely expressed in many cancers [100,101], while the vascular endothelial growth factors receptor-2 (VEGFR2) increased signaling is also characteristic of angiogenesis in tumors [102,103,104]. Alantolactone (11) (Figure 2) exhibits anti-angiogenesis property, since it shows anti-proliferative activity against human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) (IC50 = 14.2 μM), a model cell line used to study angiogenesis processes [105]. The alantolactone (11) anti-angiogenesis property could be related with its capacity to decrease capillary formation, by suppressing VEGFR2 signaling and decreasing the expression of its multiple downstream protein kinases, e.g., focal adhesion kinase (FAK) [105].

Anti-angiogenic activity is also exhibited by 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) (Figure 2) [106]. In the in vitro assay, 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) at 5 μM and 10 μM dose-dependently inhibits VEGF (25 ng/mL)-stimulated HUVEC migration, proliferation, and capillary structure formation [106]. Regarding the in vivo assay, administration for 20 consecutive days of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) (12 mg/kg b.w. per day) to A549 tumor xenografts male nude BALB/c mice cause a significant decrease in tumor cell angiogenesis and tumor growth when compared to the control group, without significant toxicity or adverse effects to the experimental animals [106]. The 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) seems to have the ability to suppress the VEGFR2 downstream Src-FAK signaling pathway, by remarkable inhibition of steroid receptor coactivator (Src) and FAK phosphorylation [106]. This last two are crucial signaling kinases in VEGF-mediated angiogenesis, by working together, or separately, to promote growth, migration, and survival of endothelial cells as well as capillary tube formation [100,101].

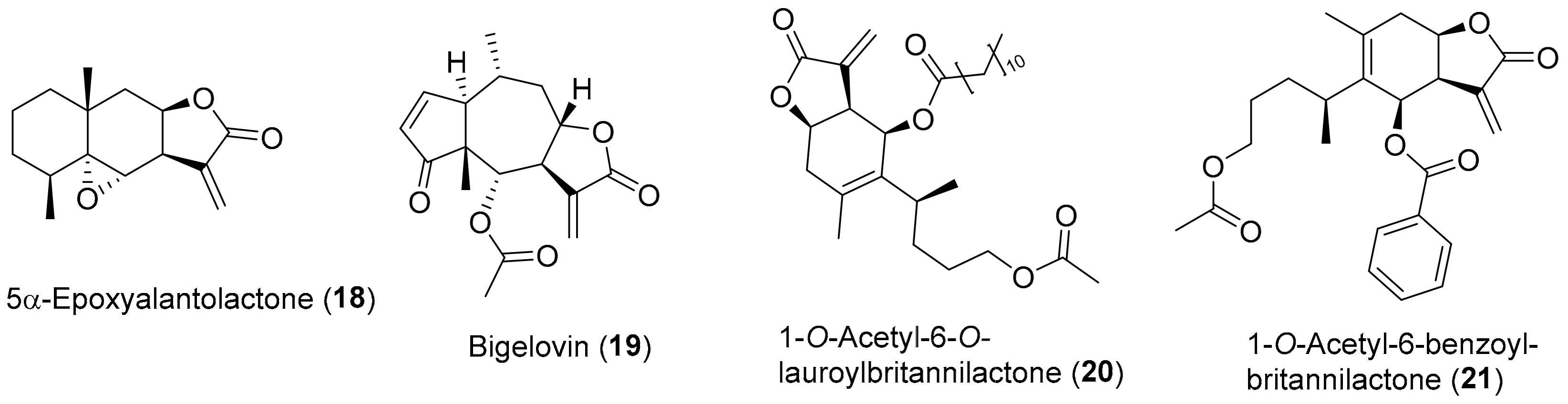

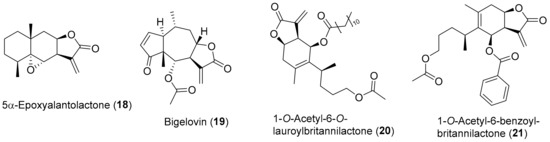

Another study [107] found that the 5α-epoxyalantolactone (18) (Figure 4), a sesquiterpene lactone isolated from the roots of Inula helenium and with a chemical structure very similar to alantolactone (11), had antiproliferative activity against human leukemia stem-like cell line KG1a. It presents an IC50 value of 3.36 ± 0.18 μM and was found to reduce the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and increased the expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax in a dose-dependent manner, while increasing the release of cytochrome into the cytoplasm, culminating in apoptosis of the cells [107].

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of Inula secondary metabolites (18–19) and semisynthetic derivatives (20–21) with reported activity against oxidative-stress carcinogenesis.

Several important physiological functions in inflammation, cell differentiation, proliferation, and cell survival, as well as apoptosis and immune modulation are mediated by many cytokines [108,109]. The activation of the cytokines signals transduction of the Janus kinase (JAK) and STAT pathway, where JAKs phosphorylate STATs, causing their activation, associated with cancer and other proliferative diseases [110,111]. A study [112] showed that bigelovin (19) (Figure 4), a very abundant sesquiterpene lactone found in several Inula species [12,13], is a potent inhibitor of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. It directly inactivates JAK2 and blocks the downstream signaling transduction pathway, blocking IL-6-induced activation of STAT3. This explains the bigelovin (19) remarkable antitumor activity against several cancer cell lines from different tissues [112,113], e.g., human lung carcinoma cell lines (A549 IC50 ≅ 4.5 μM and H460 IC50 ≅ 8.5 μM), human cervical carcinoma cell line (HeLa IC50 ≅ 3.3 μM), human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2 IC50 ≅ 7.1 μM), human breast adenocarcinoma cell line (MDA-MB-231 IC50 ≅ 1.3 μM, MDAMB-453 IC50 ≅ 2.5 μM and MDA-MB-468 IC50 ≅ 1.1 μM), and human leukemia cell lines (HL-60 IC50 ≅ 0.5 μM, Jurkat IC50 ≅ 0.9 μM and U937 IC50 ≅ 0.6 μM) [112]. Li et al. [114] showed that bigelovin (19) also acts mainly via the IL6/STAT3 pathway, significantly and effectively exerting anti-inflammatory and antitumor effects on colorectal cancer cells (CRC). In in vitro assay, cell viability, proliferation and colony formation of colon cancer cells colon-26 and its most aggressive version colon-26-M01 cells are inhibited in time- and dose-dependent manners, by bigelovin (19), with IC50 values of 0.99 ± 0.3 μM and 1.12 ± 0.33 μM, respectively [114]. In in vivo assay, the male BALB/c mice inoculated with human colon adenocarcinoma cell line HCT 116 and murine colon cancer cell line 26-M01 were subjected to treatment with bigelovin (19), at 0.3, 1, and 3 mg/kg b.w., applied every three days for 6 times. All doses significantly suppressed tumor growth and inhibited metastasis without decrease of body weight in both CRC mouse models [114].

As confirmed by all the above, several compounds isolated from Inula species exhibit relevant properties in the fight against oxidative-stress related diseases, with 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) (Figure 2) being one of the most studied compounds. The interest in this compound led to the publication of several studies on the synthesis of derivatives and evaluation of their biological activity. In some cases, the results obtained are very interesting. For example, the semisynthetic derivative 1-O-acetyl-6-O-lauroylbritannilactone (20) (Figure 4) is one of the most promising 1-O-acetyl-britannilactone derivatives (it bearing a lauroyl group at C-6 position) and exhibits cytotoxic activity against several cell lines (HCT 116, HEp-2 and HeLa), with IC50 values of 2.91 ± 0.61 μM, 5.85 ± 0.45 μM, and 6.78 ± 0.23 μM, respectively [115]. It is not so effective as etoposide (IC50 values of 2.13 ± 0.23 μM, 4.79 ± 0.54 μM, and 2.97 ± 0.25 μM, respectively) but a lot better than 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12), (IC50 values of 36.1 ± 3.1 μM, 19.3 ± 1.5 μM, and 32.6 ± 2.5 μM, respectively) [115]. It should be noticed that, at least in the case of the HCT 116 cell line, 1-O-Acetyl-6-O-lauroylbritannilactone (20) could rival etoposide while being less toxic to the CHO normal cell line (IC50 = 5.97 ± 0.12 μM) than the reference compound etoposide (IC50 = 2.60 ± 0.15 μM). In addition, 1-O-Acetyl-6-O-lauroylbritannilactone (20) was also found to cause cell-cycle arrest in the G2/M phase in HCT 116 cell line [115].

In a similar work [116], the 6-OH position of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) was modified with a variety of substituents, being the semisynthetic derivative, 1-O-acetyl-6-benzoyl-britannilactone (21) (Figure 4), the most promising antitumor derivative with IC50 values of 5.19 ± 0.10 μM and 9.93 ± 0.06 μM against HeLa and SGC-7901 cell lines, respectively, an activity level not much different from those of reference drug etoposide (HeLa IC50 = 2.97 ± 0.25 μM and SGC-7901 IC50 = 6.56 ± 0.68 μM), but it does not rival with a 5-fluorouracil drug against SGC-7901 cell line (IC50 = 0.86 ± 0.05 μM) [116]. In addition to this, it is worth mentioning that this type of approach is very interesting and worth investing in, because the adequate structural modification of the natural compounds enables the development of new affordable, efficient, and safe antineoplastic drugs [117].

As referred above, under impaired antioxidant pathways, critical cellular gene mutations can be induced by oxidative stress, which can be the major carcinogenic inductor [7,118]. However, in some cases, the increase in oxidative stress levels could also contribute to antitumor activity [119]. In fact, alantolactone (11) (Figure 2) [120] and bigelovin (19) (Figure 4) [121], two compounds described above as cytotoxic agents by antioxidant pathways, can have cytotoxic activity also through pro-oxidant pathways. These two studies [120,121], among several in the literature [119,121,122,123], are presented here as examples of a new perspective on the role of ROS, showing that in some cases, the production of ROS may be beneficial. In fact, the cytotoxic activity by pro-oxidant action opens new perspectives in research on the role of ROS species in biological systems as well as on new ways of fighting cancer. However, understanding the factors related to the cytotoxic effect by pro-oxidant mechanism and its effects in an integrated perspective require much more in-depth studies. Its discussion in more detail, although interesting, falls outside the scope of this review.

4. Conclusions

Taking into account the recent literature presented on this review regarding compounds with antioxidant properties and action mechanisms that target the reduction of the oxidative stress nature inherent to the various mentioned diseases, it should be mentioned that many aspects still require clarification and further studies. Knowledge about the interactions of the mentioned compounds with others, as well as the precise pathways through which some compounds exert their therapeutic activities remains scarce. The Inula species showed to be a good source of interesting and active compounds that act against oxidative-stress related diseases, through antioxidant mechanisms and/or other nonspecific antioxidant pathways, culminating in a melioration of the oxidative-stress induced problems. From all compounds, β-caryophyllene (2) is one of the most promising ones, since it presented higher antioxidant activity in the DPPH assay (IC50 of 1.25 ± 0.06 μM), more active than the reference ascorbic acid. Jaceoside (14) exhibits the best anti-inflammatory activity from all compounds (IC50 of 0.34 ± 0.01 μM), through inhibition of NO production. Jaceoside (14) should be taken in consideration as another promising compound for future studies regarding different bioactivities and its mechanisms of action. Alantolactone (11) is the most polyvalent compound, reporting interesting IC50 values for several bioactivities (i.e., anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, neuroprotective, and antitumoral). 1-O-acetylbritannilactone (12) can be also pointed out as a promising compound, since it can be used as a blueprint for the development of analogues with interesting properties. This work expects to highlight the relevance of Inula species as a source of compounds with relevant bioactivities against stress-oxidative related diseases.

Author Contributions

W.R.T. and A.M.L.S. conceived and wrote the paper.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT/MCT, by financial support to the cE3c centre (FCT Unit, UID/BIA/00329/2013, 2015-2018, and UID/BIA/00329/2019), and to the QOPNA research Unit (FCT UID/QUI/00062/2019) through national founds and, where applicable, co-financed by the FEDER, within the PT2020 Partnership Agreement, and to the Portuguese NMR Network.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the University of Azores and University of Aveiro.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| 3T3-L1 | Mouse adipocytes cells |

| 26-M01 | Murine aggressive colorectal cancer |

| A549 | Human lung carcinoma |

| ABTS | 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AD | Alzheimer disease |

| ADR | Adriamycin |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| BALB/c | Strain of laboratory mouse |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BV-2 | Mouse microglia cells |

| b.w. | Body weight |

| C57BL/6J | Strain of laboratory mouse |

| CB | Celecoxib |

| CHO | Normal hamster cell line |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase 2 |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DPPH | 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| DPP-IV | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| FAK | Focal adhesion kinase |

| FLIP | FLICE-inhibitory protein |

| GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSR | Glutathione reductase |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulphide |

| H460 | Human lung carcinoma |

| H9c2 | Rat cardiomyoblasts |

| HaCaT | Nontumorigenic human epidermal cells |

| HAT | Hydrogen-atom transfer |

| HCT 116 | Human colon cancer |

| HeLa | Human cervical carcinoma |

| HEp-2 | Human larynx epidermal carcinoma |

| HepG2 | Human hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HL-60 | Human acute promyelocytic leukemia |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| HUVEC | Human umbilical vascular endothelial cells |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| IKK | IκB kinase |

| IκB-α | Inhibitory κB-α |

| IL-1 | Interleukin 1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-1R | Interleukin-1 receptor |

| IL-4 | Interleukin 4 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-6R | Interleukin 6 receptor |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| Jurkat | Human acute T cell leukemia |

| K562 | Human bone marrow chronic myelogenous leukemia |

| K562/A02 | Human chronic myelogenous leukemia multidrug-resistant |

| KG1a | Human acute monocytic leukemia |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCP1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MDA-MB-231 | Human breast adenocarcinoma |

| MDA-MB-453 | Human breast metastatic carcinoma |

| MDA-MB-468 | Human breast adenocarcinoma (ethnicity: black) |

| MMP | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NCI-H716 | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PANC-1 | Human pancreatic epithelioid carcinoma |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor α |

| RAW 264.7 | Macrophage normal cell line |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| SET | Single-electron transfer |

| SGC-7901 | Gastric carcinoma |

| SH-SY5Y | Human neuroblastoma |

| SI | Selectivity index |

| SMT | 2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea sulphate |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| Src | Steroid receptor coactivator |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| SVG | Normal human glial cell |

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| THP-1 | Human acute monocytic leukemia |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| TNFR | Tumor necrosis factor receptor |

| TRAIL | TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand |

| U87 | Human primary glioblastoma |

| U118 | Human glioblastoma |

| U251 | Human glioblastoma |

| U937 | Human histiocytic lymohoma |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular endothelial growth factors receptor-2 |

| XIAP | X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein |

References

- Chandel, N.S.; Budinger, G.R.S. The cellular basis for diverse responses to oxygen. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 42, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymanska, R.; Pospíšil, P.; Kruk, J. Plant-derived antioxidants in disease prevention 2018. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, e2068370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vara, D.; Pula, G. Reactive oxygen species: Physiological roles in the regulation of vascular cells. Curr. Mol. Med. 2014, 14, 1103–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.; Mackey, M.M.; Diaz, A.A.; Cox, D.P. Hydroxyl radical is produced via the Fenton reaction in submitochondrial particles under oxidative stress: Implications for diseases associated with iron accumulation. Redox Rep. 2009, 14, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Zhang, L. Reactive oxygen species: Key regulators in vascular health and diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Wang, Z. Oxidative stress in carcinogenesis. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, T.; Biniecka, M.; Veale, D.J.; Fearon, U. Hypoxia, oxidative stress and inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 125, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro, O.M. Molecular pathways associated with oxidative stress in diabetes mellitus. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Pinto, D.C.G.A. Plant secondary metabolites as anticancer agents: Successes in clinical trials and therapeutic application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G.D. Unlocking the potential of natural products in drug discovery. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Grigore, A.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. The genus Inula and their metabolites: from ethnopharmacological to medicinal uses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 154, 286–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Metabolomic profile of the genus Inula. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 859–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Plant List. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/1.1/browse/A/Compositae/Inula/ (accessed on 16 February 2019).

- Jeelani, S.M.; Rather, G.A.; Sharma, A.; Lattoo, S.K. In perspective: Potential medicinal plant resources of Kashmir Himalayas, their domestication and cultivation for commercial exploitation. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2018, 8, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgeer; Uttra, A.M.; Ahsan, H.; Hasan, U.H.; Chaudhary, M.A. Traditional medicines of plant origin used for the treatment of inflammatory disorders in Pakistan: A review. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 38, 636–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Kang, H. Anti-neuroinflammatory effects of ethanol extract of Inula helenium L (Compositae). Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2016, 15, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, S.; Wu, G.Z.; Yang, N.; Zu, X.P.; Li, W.C.; Xie, N.; Zhang, R.R.; Li, C.W.; Hu, Z.L.; et al. Total sesquiterpene lactones isolated from Inula helenium L. attenuates 2,4-dinitrochlorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in mice. Phytomedicine 2018, 46, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, M.J.; Ahn, J.; Jang, Y.J.; Ha, T.Y.; Jung, C.H. Inula japonica Thunb. flower ethanol extract improves obesity and exercise endurance in mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.N.; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedare, S.B.; Singh, R.P. Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszowy, M.; Dawidowicz, A.L. Is it possible to use the DPPH and ABTS methods for reliable estimation of antioxidant power of colored compounds? Chem. Pap. 2018, 72, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarinath, A.V.; Rao, K.M.; Chetty, C.M.S.; Ramkanth, S.; Rajan, T.V.S.; Gnanaprakash, K. A review of in vitro antioxidant methods: Comparisons, correlations and considerations. Int. J. PharmTech. Res. 2010, 2, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Nimse, S.B.; Pal, D. Free radicals, natural antioxidants and their reaction mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27986–28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danino, O.; Gottlieb, H.E.; Grossman, S.; Bergman, M. Antioxidant activity of 1,3-dicaffeoylquinic acid isolated from Inula viscosa. Food Res. Int. 2009, 42, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojakowska, A.; Malarz, J.; Kiss, A.K. Hydroxycinnamates from elecampane (Inula helenium L.) callus culture. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahham, S.S.; Tabana, Y.M.; Iqbal, M.A.; Ahamed, M.B.K.; Ezzat, M.O.; Majid, A.S.A.; Majid, A.M.S.A. The anticancer, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of the sesquiterpene β-caryophyllene from the essential oil of Aquilaria crassna. Molecules 2015, 20, 11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priydarshi, R.; Melkani, A.B.; Mohan, L.; Pant, C.C. Terpenoid composition and antibacterial activity of the essential oil from Inula cappa (Buch-Ham. ex. D. Don) DC. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2015, 28, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Oh, Y.C.; Cho, W.K.; Ma, J.Y. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity determination of one hundred kinds of pure chemical compounds using offline and online screening HPLC assay. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, e165457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.M.; Zhang, M.L.; Shi, Q.W. Simultaneous determination of chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, alantolactone and isoalantolactone in Inula helenium by HPLC. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015, 53, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmieri, M.G.S.; Cruz, L.T.; Bertges, F.S.; Húngaro, H.M.; Batista, L.R.; da Silva, S.S.; Fonseca, M.J.V.; Rodarte, M.P.; Vilela, F.M.P.; do Amaral, M.P.H. Enhancement of antioxidant properties from green coffee as promising ingredient for food and cosmetic industries. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojakowska, A.; Malarz, J.; Zubek, S.; Turnau, K.; Kisiel, W. Terpenoids and phenolics from Inula ensifolia. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Shan, L.; Lu, M.; Shen, Y.H.; Tang, J.; Zhang, W.D. Chemical constituents from Inula cappa. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2010, 46, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, M.; Vlase, L.; Eșianu, S.; Tămaș, M. The analysis of flavonoids from Inula helenium L. flowers and leaves. Acta Med. Marisiensis 2011, 57, 319–323. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, T.; Liu, J.; Chen, D. Comparison of the antioxidant effects of quercitrin and isoquercitrin: Understanding the role of the 6”-OH group. Molecules 2016, 21, e1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, N.J.; Zhao, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Li, Y.F. Japonicins A and B from the flowers of Inula japonica. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2006, 8, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rifai, A. Identification and evaluation of in-vitro antioxidant phenolic compounds from the Calendula tripterocarpa Rupr. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 116, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.J.; Jin, H.Z.; Liu, X.H.; Zhang, W.D. Two new sesquiterpenes from Inula salsoloides and their inhibitory activities against NO production. Helv. Chim. Acta 2011, 94, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Islam, M.N.; Ali, M.Y.; Kim, Y.M.; Park, H.J.; Sohn, H.S.; Jung, H.A. The effects of C-glycosylation of luteolin on its antioxidant, anti-Alzheimer’s disease, anti-diabetic, and anti-inflammatory activities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, V.; Trendafilova, A.; Todorova, M.; Danova, K.; Dimitrov, D. Phytochemical profile of Inula britannica from Bulgaria. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.M.; Zhang, D.Q.; Zha, J.P.; Qi, J.L. Simultaneous HPLC determination of five flavonoids in Flos Inulae. Chromatographia 2007, 66, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive oxygen species in metabolic and inflammatory signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzhitov, R. Inflammation 2010: new adventures of an old flame. Cell 2010, 140, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, M.A.; Sousa, L.P.; Pinho, V.; Perretti, M.; Teixeira, M.M. Resolution of inflammation: What controls its onset? Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, R.H.; Schradin, C. Chronic inflammatory systemic diseases: An evolutionary trade-off between acutely beneficial but chronically harmful programs. Evol. Med. Public Health 2016, 2016, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, J.N.; Al-Omran, A.; Parvathy, S.S. Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2007, 15, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciotti, E.; FitzGerald, G.A. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 986–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goradel, N.H.; Najafi, M.; Salehi, E.; Farhood, B.; Mortezaee, K. Cyclooxygenase-2 in cancer: a review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 5683–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todoric, J.; Antonucci, L.; Karin, M. Targeting inflammation in cancer prevention and therapy. Cancer Prev. Res. 2016, 9, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G.; Roy, K.; Kumar, G.; Kumari, P.; Alam, S.; Kishore, K.; Panjwani, U.; Ray, K. Distinct influence of COX-1 and COX-2 on neuroinflammatory response and associated cognitive deficits during high altitude hypoxia. Neuropharmacology 2019, 146, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, E.H.; Lee, M.H.; Kundu, J.K.; Na, H.K.; Cha, Y.N.; Surh, Y.J. Sulforaphane inhibits phorbol ester-stimulated IKK-NF-κB signaling and COX-2 expression in human mammary epithelial cells by targeting NF-κB activating kinase and ERK. Cancer Lett. 2014, 351, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Okuda, J.; Kurazumi, T.; Suhara, T.; Ueda, T.; Nagata, H.; Morisaki, H. Sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction and β-adrenergic blockade therapy for sepsis. J. Intensive Care 2017, 5, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-H.; Xu, M.; Wu, H.-M.; Wan, C.-X.; Wang, H.-B.; Wu, Q.-Q.; Liao, H.-H.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q.-Z. Isoquercitrin attenuated cardiac dysfunction via AMPKα-dependent pathways in LPS-treated mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.-W.; Qin, J.-J.; Cheng, X.-R.; Shen, Y.-H.; Shan, L.; Jin, H.-Z.; Zhang, W.-D. Inula sesquiterpenoids: structural diversity, cytotoxicity and anti-tumor activity. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2014, 23, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-D.; Qin, J.-J.; Jin, H.-Z.; Yin, Y.-H.; Li, H.-L.; Yang, X.-W.; Li, X.; Shan, L.; Zhang, W.-D. Sesquiterpenoids from Inula racemosa Hook. f. inhibit nitric oxide production. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Choi, R.J.; Khan, S.; Lee, D.-S.; Kim, Y.-C.; Nam, Y.-J.; Lee, D.-U.; Kim, Y.S. Alantolactone suppresses inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 expression by down-regulating NF-κB, MAPK and AP-1 via the MyD88 signaling pathway in LPS-activated RAW 264.7 cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012, 14, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Han, M.; Sun, R.-H.; Wang, J.-J.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Zhang, D.-Q.; Wen, J.-K. ABL-N-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells is partially mediated by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation. Breast Cancer Res. 2010, 12, R9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.-M.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.-B.; Wang, J.-J.; Wen, J.-K.; Li, B.-H.; Han, M. Acetylbritannilactone suppresses growth via upregulation of krüppel-like transcription factor 4 expression in HT-29 colorectal cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.L.; Hussain, J.; Hamayun, M.; Gilani, S.A.; Ahmad, S.; Rehman, G.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kang, S.-M.; Lee, I.-J. Secondary metabolites from Inula britannica L. and their biological activities. Molecules 2010, 15, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wen, J.K.; Li, B.H.; Fang, X.M.; Wang, J.J.; Zhang, Y.P.; Shi, C.J.; Zhang, D.Q.; Han, M. Celecoxib and acetylbritannilactone interact synergistically to suppress breast cancer cell growth via COX-2-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.-P.; Chen, Y.-F.; Zhu, H.; Wu, X.-R.; Yu, Y.; Kong, D.-X.; Duan, H.-Q.; Jin, M.-H.; Qin, N. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory activities of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone analogues. Phytochem. Lett. 2017, 19, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garayev, E.; Di Giorgio, C.; Herbette, G.; Mabrouki, F.; Chiffolleau, P.; Roux, D.; Sallanon, H.; Ollivier, E.; Elias, R.; Baghdikian, B. Bioassay-guided isolation and UHPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS quantification of potential anti-inflammatory phenolic compounds from flowers of Inula montana L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 226, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Lee, J.W.; Jang, H.; Lee, H.L.; Kim, J.G.; Wu, W.; Lee, D.; Kim, E.-H.; Kim, Y.; Hong, J.T.; Lee, M.K.; Hwang, B.Y. Dimeric- and trimeric sesquiterpenes from the flower of Inula japonica. Phytochemistry 2018, 155, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharroubi, A.T.; Darwish, H.M. Diabetes mellitus: The epidemic of the century. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, C.M.O.; Villar-Delfino, P.H.; dos Anjos, P.M.F.; Nogueira-Machado, J.A. Cellular death, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and diabetic complications. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnert, K.-D.; Freyse, E.-J.; Salzsieder, E. Glycaemic variability and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2012, 8, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Sears, D.D. TLR4 and insulin resistance. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2010, 2010, 212563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Chen, R.; Wang, H.; Liang, F. Mechanisms linking inflammation to insulin resistance. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 508409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Choi, S.E.; Ha, E.S.; Jung, J.G.; Han, S.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, K.W. IL-6 induction of TLR-4 gene expression via STAT3 has an effect on insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle. Acta Diabetol. 2013, 50, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuñiga, L.Y.; Aceves-de la Mora, M.C.; González-Ortiz, M.; Ramos-Núñez, J.L.; Martínez-Abundis, E. Effect of chlorogenic acid administration on glycemic control, insulin secretion, and insulin sensitivity in patients with impaired glucose tolerance. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.M.H.; Sun, R.-Q.; Zeng, X.-Y.; Choong, Z.-H.; Wang, H.; Watt, M.J.; Ye, J.-M. Activation of PPARα ameliorates hepatic insulin resistance and steatosis in high fructose-fed mice despite increased endoplasmic reticulum stress. Diabetes 2013, 62, 2095–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Yan, Z.; Zhong, J.; Chen, J.; Ni, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, L.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhu, Z. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activation enhances gut glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion and improves glucose homeostasis. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2155–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, C.F.; Mannucci, E.; Ahrén, B. Glycaemic efficacy of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors as add-on therapy to metformin in subjects with type 2 diabetes-a review and meta analysis. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012, 14, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.-T.; Yin, Y.-C.; Xing, S.; Li, W.-N.; Fu, X.-Q. Hypoglycemic effect and mechanism of isoquercitrin as an inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 in type 2 diabetic mice. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 14967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-L.; He, Y.; Ji, L.-L.; Wang, K.-Y.; Wang, Y.-L.; Chen, D.-F.; Geng, Y.; OuYang, P.; Lai, W.-M. Hepatoprotective potential of isoquercitrin against type 2 diabetes-induced hepatic injury in rats. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 101545–101559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Song, K.; Kim, Y.S. Alantolactone improves prolonged exposure of interleukin-6-induced skeletal muscle inflammation associated glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gu, B.J.; Masters, C.L.; Wang, Y.-J. A systemic view of Alzheimer disease - insights from amyloid-β metabolism beyond the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017, 13, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, R.K.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial diseases of the brain. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 63, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, S.; Guillemin, G.J.; Abiramasundari, R.S.; Essa, M.M.; Akbar, M.; Akbar, M.D. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease: a mini review. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, e8590578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, J.Y.; Lim, S.S.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, J.-S. Alantolactone and isoalantolactone prevent amyloid β25-35-induced toxicity in mouse cortical neurons and scopolamine-induced cognitive impairment in mice. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; An, C.; Gao, Y.; Leak, R.K.; Chen, J.; Zhang, F. Emerging roles of Nrf2 and phase II antioxidant enzymes in neuroprotection. Prog. Neurobiol. 2013, 100, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-G.; Laird, M.D.; Han, D.; Nguyen, K.; Scott, E.; Dong, Y.; Dhandapani, K.M.; Brann, D.W. Critical role of NADPH oxidase in neuronal oxidative damage and microglia activation following traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lan, Y.-L.; Xing, J.-S.; Lan, X.-Q.; Wang, L.-T.; Zhang, B. Alantolactone plays neuroprotective roles in traumatic brain injury in rats via anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and anti-apoptosis pathways. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2018, 10, 368–380. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.-S.; Xie, K.-Q.; Zhang, C.-L.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Zhang, L.-P.; Guo, X.; Yu, S.-F. Allyl chloride-induced time dependent changes of lipid peroxidation in rat nerve tissue. Neurochem. Res. 2005, 30, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ighodaro, O.M.; Akinloye, O.A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J. Med. 2018, 54, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadfar, S.; Hwang, C.J.; Lim, M.-S.; Choi, D.-Y.; Hong, J.T. Involvement of inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and therapeutic potential of anti-inflammatory agents. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 2106–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Dong, B.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jin, D.-Q.; Ohizumi, Y.; Lee, D.; Xu, J.; Guo, Y. NO inhibitors function as potential anti-neuroinflammatory agents for AD from the flowers of Inula japonica. Bioorg. Chem. 2018, 77, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, M.; Hayes, A.; Caprnda, M.; Petrovic, D.; Rodrigo, L.; Kruzliak, P.; Zulli, A. Inducible nitric oxide synthase: Good or bad? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 93, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Shimizu, M.; Kochi, T.; Moriwaki, H. Chemical-induced carcinogenesis. J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2013, 5, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Badana, A.K.; Gavara, M.M.; Gugalavath, S.; Malla, R. Reactive oxygen species: A key constituent in cancer survival. Biomark. Insights 2018, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Bae, J.-S. ROS homeostasis and metabolism: a critical liaison for cancer therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafani, M.; Sansone, L.; Limana, F.; Arcangeli, T.; De Santis, E.; Polese, M.; Fini, M.; Russo, M.A. The interplay of reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, inflammation, and sirtuins in cancer initiation and progression. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2016, 2016, e3907147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, C.; Cheng, W.; Tian, X.; Huo, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Feng, L.; Xing, J.; et al. Alantolactone, a natural sesquiterpene lactone, has potent antitumor activity against glioblastoma by targeting IKKβ kinase activity and interrupting NF-κB/COX-2-mediated signaling cascades. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 36, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Vasdev, N.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q. Alantolactone selectively ablates acute myeloid leukemia stem and progenitor cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, H.; Qiao, J.-O. 1-O-Acetylbritannilactone combined with gemcitabine elicits growth inhibition and apoptosis in A549 human non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5568–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, M.; Mousa, S.A. The role of angiogenesis in cancer treatment. Biomedicines 2017, 5, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albini, A.; Tosetti, F.; Li, V.W.; Noonan, D.M.; Li, W.W. Cancer prevention by targeting angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 9, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sennino, B.; McDonald, D.M. Controlling escape from angiogenesis inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cébe-Suarez, S.; Zehnder-Fjällman, A.; Ballmer-Hofer, K. The role of VEGF receptors in angiogenesis; complex partnerships. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, C.; Ongaro, E.; Bolzonello, S.; Guardascione, M.; Fasola, G.; Aprile, G. Clinical advances in the development of novel VEGFR2 inhibitors. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, C.; Simiantonaki, N.; Habedank, S.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. The relevance of cell type- and tumor zone-specific VEGFR-2 activation in locally advanced colon cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 34, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-R.; Cai, Q.-Y.; Gao, Y.-G.; Luan, X.; Guan, Y.-Y.; Lu, Q.; Sun, P.; Zhao, M.; Fang, C. Alantolactone, a sesquiterpene lactone, inhibits breast cancer growth by antiangiogenic activity via blocking VEGFR2 signaling. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhengfu, H.; Hu, Z.; Huiwen, M.; Zhijun, L.; Jiaojie, Z.; Xiaoyi, Y.; Xiujun, C. 1-o-acetylbritannilactone (ABL) inhibits angiogenesis and lung cancer cell growth through regulating VEGF-Src-FAK signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 464, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Pan, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, T.; Chen, T.; Liu, Z.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Q. Sesquiterpenoids from the roots of Inula helenium inhibit acute myelogenous leukemia progenitor cells. Bioorg. Chem. 2019, 86, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindler, C.; Levy, D.E.; Decker, T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20059–20063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoops, L.; Hornakova, T.; Royer, Y.; Constantinescu, S.N.; Renauld, J.-C. JAK kinases overexpression promotes in vitro cell transformation. Oncogene. 2008, 27, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wang, T.; Niu, G.; Kortylewski, M.; Burdelya, L.; Shain, K.; Zhang, S.; Bhattacharya, R.; Gabrilovich, D.; Heller, R.; Coppola, D.; Dalton, W.; Jove, R.; Pardoll, D.; Yu, H. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat-3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, R.L.; Pardanani, A.; Tefferi, A.; Gilliland, D.G. Role of JAK2 in the pathogenesis and therapy of myeloproliferative disorders. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007, 7, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-H.; Kuang, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.-X.; Gu, Y.; Hu, L.-H.; Yu, Q. Bigelovin inhibits STAT3 signaling by inactivating JAK2 and induces apoptosis in human cancer cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.-Z.; Tan, N.-H.; Ji, C.-J.; Fan, J.-T.; Huang, H.-Q.; Han, H.-J.; Zhou, G.-B. Apoptosis inducement of bigelovin from Inula helianthus-aquatica on human leukemia U937 cells. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yue, G.G.-L.; Song, L.-H.; Huang, M.-B.; Lee, J.K.-M.; Tsui, S.K.-W.; Fung, K.-P.; Tan, N.-H.; Lau, C.B.-S. Natural small molecule bigelovin suppresses orthotopic colorectal tumor growth and inhibits colorectal cancer metastasis via IL6/STAT3 pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 150, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Tang, J.-J.; Zhang, C.-C.; Tian, J.-M.; Guo, J.-T.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Gao, J.-M. Semisynthesis and in vitro cytotoxic evaluation of new analogues of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone, a sesquiterpene from Inula britannica. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 80, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.-J.; Dong, S.; Han, Y.-Y.; Lei, M.; Gao, J.-M. Synthesis of 1-O-acetylbritannilactone analogues from Inula britannica and in vitro evaluation of their anticancer potential. Med. Chem. Commun. 2014, 5, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.E. Design and synthesis of analogues of natural products. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 5302–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Wang, Z.; Pu, X.; Zhou, S. Oxidative stress and oxidative damage in chemical carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 254, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.; Cao, F.; Li, M.; Li, P.; Xu, T.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Gu, B.; Yu, X.; Cai, X.; et al. Enhanced mitochondrial pyruvate transport elicits a robust ROS production to sensitize the antitumor efficacy of interferon-γ in colon cancer. Redox Biol. 2019, 20, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Bu, W.; Song, J.; Feng, L.; Xu, T.; Liu, D.; Ding, W.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Ma, B.; et al. Apoptosis induction by alantolactone in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells through reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrion-dependent pathway. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018, 41, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Song, L.H.; Yue, G.G.L.; Lee, J.K.M.; Zhao, L.M.; Li, L.; Zhou, X.; Tsui, S.K.W.; Ng, S.S.-M.; Fung, K.-P.; et al. Bigelovin triggered apoptosis in colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo via upregulating death receptor 5 and reactive oxidative species. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, J. Alantolactone induces apoptosis of human cervical cancer cells via reactive oxygen species generation, glutathione depletion and inhibition of the Bcl-2/Bax signaling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 4203–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Duan, D.; Yao, J.; Gao, K.; Fang, J. Inhibition of thioredoxin reductase by alantolactone prompts oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis of HeLa cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 102, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).