Olive Tree (Olea europeae L.) Leaves: Importance and Advances in the Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

Abstract

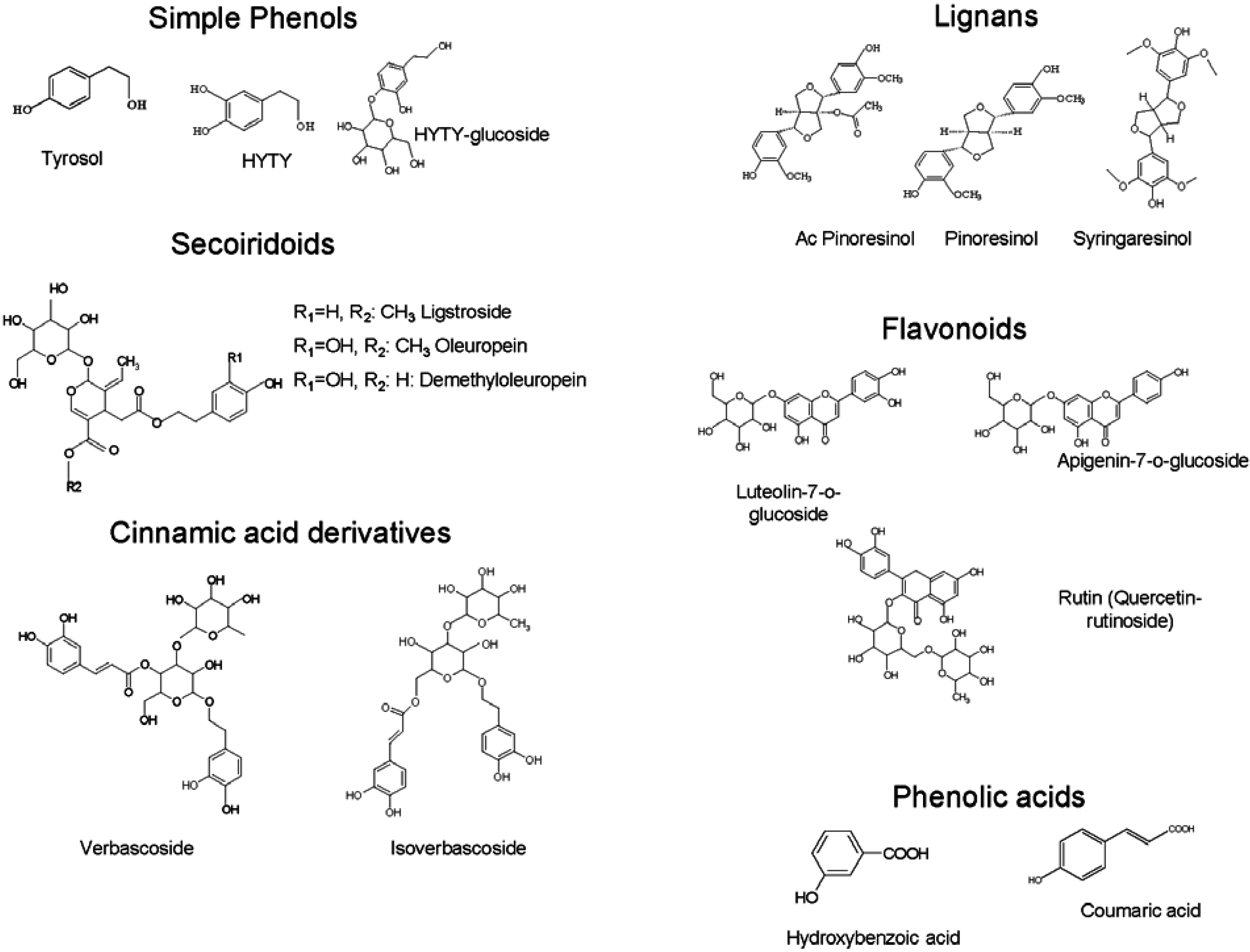

:1. Olive Leaves as a Potential Source of Phenolic Compounds

2. Sample Preparation

| Objectives of the Research | Drying Process and Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Study the effect of blanching and/or infrared drying on the color, total phenols content and the moisture removal rate of four olive leaf varieties | Infrared dryer Infrared drying temperatures: 40, 50, 60 and 70 °C | [29] |

| Investigate the main effects of process variables on the product quality during heat pump drying of olive leaves Determine an optimum process conditions for drying of olive leaves in a pilot scale heat pump conveyor dryer | Pilot scale heat pump conveyor dryer Drying air temperature range: 45–55 °C Drying air velocity range: 0.5–1.5 m/s Time range: 270–390 min | [30] |

| Investigate the main effects of process variables on the product quality during hot air drying of olive leaves Determine an optimum process conditions for drying of olive leaves in a tray drier | Laboratory-type tray dryer Drying compartment dimensions: 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.4 m Drying air temperatures: 40–60 °C Drying air velocities: 0.5–1.5 m/s Process time: 240–480 min | [31] |

| Study the influence of the ultrasound power application during the drying of olive leaves in the kinetics of process | Pilot scale convective dryer modified to apply power ultrasound Drying temperature: 40 °C Air velocity: 1 m/s Levels of electrical power applied to the ultrasound transducer: 0, 20, 40, 60 and 80 W Ultrasonic power density in drying chamber: 0, 8, 16, 25 and 33 kW/m3 | [27] |

| Determine and test the most appropriate thin-layer drying model. Reveal the effects of drying air temperature and velocity on the effective diffusion coefficient and activation energy for understanding the drying behavior of olive leaves | Thin-layer dryer Drying air temperatures: 50, 60 or 70 °C Drying air velocities: 0.5, 1.0 or 1.5 m/s | [28] |

| Investigate the effect of solar drying conditions on the drying time and some quality parameters of olive leaves particularly the color, total phenol content and radical scavenging activity | Laboratory convective Solar Dryer Drying air temperatures: 40, 50 and 60 °C Drying air velocities: 1.6 and 3.3 m3/min | [26] |

| Develop a direct and rapid tool to discriminate five Tunisian cultivars according to their olive leaves by using FT-MIR spectroscopy associated to chemometric treatment | Microwave Two times for 2 min Maximum power 800 W (2450 MHz) | [32] |

| Study the effect of freezing and drying of olive leaves on the antioxidant potential of extracts Choose an appropriate drying process to obtain extracts rich in bioactive compounds | -

Hot air drying by forced air laboratory dryer 70 °C for 50 min and at 120 °C for 12 min Air flow: 0.094 m3/s Air velocity: 0.683 m/s -Freeze air drying by freeze dryer chamber Initial temperature: −48 ± 2 °C, shelf temperature set at 22 ± 2 °C. Time: 48 h and Pressure: 1.4 × 10−1 mbar | [33] |

3. Extraction Procedures

| Extraction Technique | Analytical Technique | Observations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extractant solvents: ethanol, methanol, acetone and their aqueous form (10%–90%, v/v). Extraction time: 24 h | HPLC-UV (280 nm) Stationary phase: C18 Lichrospher 100 analytical column (250 × 4 mm, 5 μm) at 30 °C Flow rate:1 mL/min Mobile phases: acetic acid/water (2.5:97.5) (A)and acetonitrile (B) Elution: gradient Total time: 60 min | 70% ethanol as extractant solvent for high content of phenolics and antioxidant capacity. oleuropein (13.4%), rutin (0.18%). Silk fibroin was found to be a promising adsorbent for the purification of oleuropein and rutin from olive leaf extracts | [38] |

| 30–50 mg of olive leaves powder | Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy Mid-infrared spectra were recorded between 4000 cm−1 and 700 cm−1 Nominal resolution was 4 cm−1 | Mid-infrared spectroscopy, as a rapid tool, to predict oleuropein content in olive leaf from five Tunisian cultivars (Chemlali, Chetoui, Meski, Sayali and Zarrazi) Oleuropein: 8.72% and 17.95% | [34] |

| 0.5 g of dry leaves extracted via Ultra-Turrax 10 mL of MeOH/H2O (80/20) Ultrasonic bath (10 min) Extraction repeated twice | HPLC-DAD-ESI-TOF- MS Stationary phase: Poroshell 120 EC-C18 analytical column (4.6 × 100 mm, 2.7 μm) (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) Mobile phases: acidified in water (acetic acid 1%) (phase A) and acetonitrile (phase B) Elution: gradient Flow rate: 0.8 mL/min | 30 phenolic compounds were identified. Total phenolic compounds: 52.12–60.64 mg/kg | [39] |

| Fresh leaves in aqueous methanol 80% | HPLC-DAD (240, 254, 280, 330 and 350 nm) MS (MSD API-electro spray) and NMR Stationary phase: Zorbax Stablebond SB-C18 column (5 µm; 250 × 4.6 mm (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) Mobile phases: acidified water (pH 3.2 by formic acid (A)), methanol (B) and acetonitrile (C) Elution: gradient Flow rate: 0.8 mL/min | Novel secoiridoid glucosides identified as a physiological response to nutrient stress | [40] |

| MAE 1.25 g of milled fresh olive leaves, 10 mL of methanol, ethanol and their aqueous form (40%–100%). Extraction time: 4–16 min, Irradiation temperature: 10–120 °C. | HPLC-ESI-TOF/IT-MS Stationary phase: C18 Eclipse Plus analytical column, Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) (4.6 × 150 mm, 1.8 μm) at 25 °C, Mobile phases: acetic acid (0.5%) (A) and acetonitrile (B) Elution: gradient Flow rate 0.8 mL/min | Univariate optimisation for phenolics extraction: methanol: water (80%) at 80 °C for 6 min 36 compounds | [41] |

| MAE Power 100–200 W, irradiation time 5–15 min, ethanol 80%–100% | HPLC-DAD (280, 330, 340 and 350 nm) Stationary phase: Lichrospher 100 RP18, Análisis Vínicos, Ciudad Real, Spain (250 × 4 mm,5 μm), Kromasil 5 C18 column, Scharlab, Barcelona, Spain (15 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) Mobile phases: 6% acetic acid, 2 mM sodium acetate, in water (A) and acetonitrile (B) Elution: gradient Flow rate 0.8 mL/min GC-IT-MS # Stationary phase: fused-silica capillary column, Varian, TX, USA (VF-5 ms, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm) | Multivariate optimization for extraction of oleuropein and related biophenols: 200 W for 8 min, ethanol 80%, oleuropein 2.32%, verbacoside 631 mg/kg, apigenin-7-glucoside 1076 mg/kg, luteolin-7-glucoside 1016 mg/kg) Simple phenols were not found in the extracts obtained by MAE | [42] |

| USAE solvent concentration: 0–100% ethanol Ratio of solid to solvent: 25–50 mg/mL Extraction time: 20–60 min Frequency: 50 Hz | UV spectrometry (Folin–Ciocalteu) | Multivariate optimization: 50% EtOH, 500 mg dried leaf to 10 mL solvent, and 60 min Solvent concentration was proved to be the most significant parameter of all the parameters used | [43] |

| DUSAE (20 kHz, 450 W) Tested variables: probe position: 0–4 cm ultrasound radiation amplitude: 10%–50% Duty cycle: 30%–70% Irradiation time: 6–30 min Extractant flow- rate: 4–6 mL/min Ethanol: 50%–90% Water bath: temperature: 25–40 °C | HPLC–DAD (280, 330, 340 and 350 nm) Stationary phase: Lichrospher 100 RP18 (250 × 4 mm,5 μm), Kromasil 5 C18 column (15 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) Mobile phases: 6% acetic acid, 2 mM sodium acetate, in water (A) and acetonitrile (B) Elution: gradient Flow rate: 0.8 mL/min GC-IT-MS Stationary phase: fused-silica capillary column (VF-5 ms, 30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm) Carrier gas: Helium (1 mL/min) Ionisation: electron impact | Multivariate methodology optimization: 1 g of milled leaves in a 59:41 ethanol–water mixture, bath temperature 40 °C, extraction time 25 min, ultrasonic irradiation (duty cycle 0.7 s, output amplitude 30% of the converter, applied power 450 W. Target analytes concentration:oleuropein, verbacoside, apigenin-7-glucoside and luteolin-7-glucoside contents: 22610 ± 632, 488 ± 21, 1072 ± 38 and 970 ± 43 mg/kg; respectively | [44] |

| SFE 1 g of milled olive leaves Pressure and temperature: 150 bar and 40 °C Extraction solvent: CO2 + 6.6% of ethanol as modifier Extraction time: 2 h | HPLC-ESI-TOF/IT-MS Stationary phase: C18 Eclipse Plus analytical column (4.6 × 150 mm, 1.8 μm) at 25 °C Mobile phases: acetic acid (0.5%) (A) and acetonitrile (B) Elution: gradient Flow rate 0.8 mL/min | Compared to other extraction techniques MAE, CM and PLE, SFE was the best extraction procedure for apigenin and diosmetin isolation | [45] |

| SFE Pressure: 30 MPa Extraction temperature: 50°C Separation temperature: 55°C Mode: dynamic Variables: solvent-to-feed ratio, 120 or 290; co-solvent: 5% or 20% | HPLC-DAD (248 nm) Stationary phase: SupelcoAnalytical Discovery HS C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 μm) at 25 °C Mobile phases: H2O + 1% acetic acid (A) and MeOH (B) Elution: gradient Flow rate: 1 mL/min | Pressure: 30 MPa, extraction temperature: 50°C, separation temperature: 55 °C, mode: dynamic, solvent-to-feed ratio: 290, co-solvent: 20% Oleuropein 30% | [46] |

| PLE: 1 g of grinded olive leaves Solvent: ethanol or water Pressure 100 bar, temperature 150 °C time Extraction time: 20 min | HPLC-ESI-TOF/IT-MS Stationary phase: C18 Eclipse Plus analytical column (4.6 × 150 mm, 1.8 μm) at 25 °C Mobile phases: acetic acid (0.5%) (A) and acetonitrile (B) Elution: gradient Flow rate 0.8 mL/min MS: negative mode | PLE (using ethanol as solvent) produced the highest yield for all the studied varieties. PLE (using water as solvent) did not show a good efficiency either for extracting oleuropein. | [45] |

| PLE Ethanol (150 °C) Water (200 °C) Extraction time: 20 min | HPLC–ESI–QTOF–MS Stationary phase: C18 (3 μm, 2 × 150 mm) at 25 °C Elution: gradient elution program at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The mobile phases consisted of water plus 0.5% acetic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B) MS: negative mode | The first time that lucidumoside C has been detected in olive leaves The ethanolic extract has proven to be especially rich in flavonoids, while the aqueous extract was richer in hydroxytyrosol. | [47] |

| PLE 6 g of grinded olive leaves Variables: temperature, static time, extraction cycles and EtOH (%) Pressure 1500 psi | HPLC-DAD (248 nm) Stationary phase: Supelco Analytical Discovery HS C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 μm) at 25 °C Mobile phases: H2O + 1% acetic acid (A) and MeOH (B) Mode: gradient Flow rate: 1 mL/min | Multivariate optimization The extraction yield is mainly influenced by 3 factors (in the order of statistical significance): temperature, static time and extraction cycles. The effect is positive in all three cases. oleuropein: 26.1% | [48] |

| SHLE Tested variables: temperature, static and dynamic extraction time, extractant flow-rate and extractant composition | HPLC–DAD (280, 330, 340 and 350 nm) Stationary phase: Lichrospher 100 RP18 (250 × 4 mm,5 μm), Kromasil 5 C18 column (15 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) Mobile phases: 6% acetic acid, 2 mM sodium acetate, in water (A) and acetonitrile (B) Elution: gradient Flow rate: 0.8 mL/min | Multivariate optimization 1 g of leaves , Pressure: 6 bar , 70:30 ethanol–water, temperature 140 °C, 6 min Dynamic mode,extractant for 7 min at 1 mL/min, Extraction time: 13 min 23 g/kg of oleuropein, 665 mg/kg of verbascoside, 1046 mg/kg of apigenin-7-glucoside, 998 mg/kg of luteolin-7-glucoside | [49] |

4. Determination of Phenolic Compounds

5. Exploitation of Bioactive Components

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balasundram, N.; Sundram, K.; Samman, S. Phenolic compounds in plants and agri-industrial by-products: Antioxidant activity, occurrence, and potential uses. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero, M.; Temirzoda, T.N.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Quirantes, R.; Plaza, M.; Ibañez, E. New possibilities for the valorization of olive oil by-products. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 7511–7520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peralbo-Molina, Á.; de Castro, M.D. Potential of residues from the Mediterranean agriculture and agrifood industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 32, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.P.; Ferreira, I.C.; Marcelino, F.; Valentão, P.; Paula, B.; Seabra, R.; Estevinho, L.; Bento, A.; Pereira, J.A. Phenolic Compounds and Antimicrobial Activity of Olive (Olea europaea L. Cv. Cobrançosa) Leaves. Molecules 2007, 12, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulotta, S.; Corradino, R.; Celano, M.; D’Agostino, M.; Maiuolo, J.; Oliverio, M.; Procopio, A.; Iannone, M.; Rotiroti, D.; Russo, D. Antiproliferative and antioxidant effects on breast cancer cells of oleuropein and its semisynthetic peracetylated derivatives. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemai, H.; El Feki, A.; Sayadi, S. Antidiabetic and antioxidant effects of hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein from olive leaves in alloxan-diabetic rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 8798–8804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemai, H.; Fki, I.; Bouaziz, M.; Bouallagui, Z.; El Feki, A.B.; Isoda, H.; Sayadi, S. Lipid-Lowering and Antioxidant Effects of Hydroxytyrosol and Its Triacetylated Derivative Recovered from Olive Tree Leaves in Cholesterol-Fed Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, O.-H.; Lee, B.-Y. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of individual and combined phenolics in Olea europaea leaf extract. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 3751–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavente-garcía, O.; Castillo, J.; Lorente, J.; Ortuno, A.; del Rio, J.A. Antioxidant activity of phenolics extracted from Olea europaea L. leaves. Food Chem. 2000, 68, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.J.; Alcaraz, M.; Benavente-garcía, O. Antioxidant and Radioprotective Effects of Olive Leaf Extract; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Huang, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, P.L.; Chang, Y.-T.; Huang, P.L. Anti-HIV activity of olive leaf extract (OLE) and modulation of host cell gene expression by HIV-1 infection and OLE treatment. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 307, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Talorete, T.P.N.; Yamada, P.; Isoda, H. Anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol on human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Cytotechnology 2009, 59, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abaza, L.; Talorete, T.P.N.; Yamada, P.; Kurita, Y.; Zarrouk, M.; Isoda, H. Induction of Growth Inhibition and Differentiation of Human Leukemia HL-60 Cells by a Tunisian Gerboui Olive Leaf Extract. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2007, 71, 1306–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antolovich, M.; Prenzler, P.; Robards, K.; Ryan, D. Sample preparation in the determination of phenolic compounds in fruits. Analyst 2000, 125, 989–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimidou, M.Z.; Papoti, V.T. Bioactive Ingredients in Olive Leaves; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- El, S.N.; Karakaya, S. Olive tree (Olea europaea) leaves: Potential beneficial effects on human health. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontogianni, V.G.; Gerothanassis, I.P. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of olive leaf extracts. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savournin, C.; Baghdikian, B.; Elias, R.; Dargouth-Kesraoui, F.; Boukef, K.; Balansard, G. Rapid high-performance liquid chromatography analysis for the quantitative determination of oleuropein in Olea europaea leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmi, F.; Mechri, B.; Dabbou, S.; Dhibi, M.; Hammami, M. The efficacy of phenolics compounds with different polarities as antioxidants from olive leaves depending on seasonal variations. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 38, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.; Gomes, L.; Leitao, F.; Coelho, A.V.; Boas, L.V. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Olea europaea L. Fruits and Leaves. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2006, 12, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, M.; Şahin, S. Effects of geographical origin and extraction methods on total phenolic yield of olive tree (Olea europaea) leaves. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2013, 44, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, Z.; Jafari, S.M.; Alami, M.; Khomeiri, M. Microwave-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from olive leaves; a comparison with maceration. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2011, 21, 738–745. [Google Scholar]

- Japón-Lujan, R.; Ruiz-Jiménez, J.; de Castro, M.D.L. Discrimination and classification of olive tree varieties and cultivation zones by biophenol contents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 9706–9712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad-Qasem, M.H.; Barrajon-Catalan, E.; Micol, V.; Cárcel, J.A.; Garcia-Perez, J.V. Influence of air temperature on drying kinetics and antioxidant potential of olive pomace. J. Food Eng. 2013, 119, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, Z.; Icier, F. The Importance and Potential Uses of Olive Leaves. Food Rev. Int. 2010, 26, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, N.; Boudhrioua, N.; Kouhila, M.; Kechaou, N. Effect of convective solar drying on colour, total phenols and radical scavenging activity of olive leaves (Olea europaea L.). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 44, 2561–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárcel, J.A.; Nogueira, R.I.; García-Pérez, J.V.; Sanjuán, N.; Riera, E. Ultrasound Effects on the Mass Transfer Processes during Drying Kinetic of Olive Leaves (Olea Europea, var. Serrana). Defect Diffus. Forum 2010, 297–301, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, Z.; Icier, F. Thin-Layer Drying Behaviors of Olive Leaves (Olea europaea L.). J. Food Process Eng. 2010, 33, 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudhrioua, N.; Bahloul, N.; Ben Slimen, I.; Kechaou, N. Comparison on the total phenol contents and the color of fresh and infrared dried olive leaves. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 29, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, Z.; Icier, F. Optimization of Drying of Olive Leaves in a Pilot-Scale Heat Pump Dryer. Dry. Technol. 2009, 27, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, Z.; Icier, F. Optimization of hot air drying of olive leaves using response surface methodology. J. Food Eng. 2009, 91, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouidi, F.; Dupuy, N.; Artaud, J.; Roussos, S.; Msallem, M.; Perraud-Gaime, I.; Hamdi, M. Discrimination of five Tunisian cultivars by mid infraRed spectroscopy combined with chemometric analyses of olive Olea europaea leaves. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad-Qasem, M.H.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Micol, V.; Mulet, A.; García-Pérez, J.V. Influence of freezing and dehydration of olive leaves (var. Serrana) on extract composition and antioxidant potential. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouidi, F.; Dupuy, N.; Artaud, J.; Roussos, S.; Msallem, M.; Perraud Gaime, I.; Hamdi, M. Rapid quantitative determination of oleuropein in olive leaves (Olea europaea) using mid-infrared spectroscopy combined with chemometric analyses. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 37, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huie, C.W. A review of modern sample-preparation techniques for the extraction and analysis of medicinal plants. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 373, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Salas, P.; Morales-Soto, A.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Phenolic-compound-extraction systems for fruit and vegetable samples. Molecules 2010, 15, 8813–8826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altıok, E.; Bayçın, D.; Bayraktar, O.; Ülkü, S. Isolation of polyphenols from the extracts of olive leaves (Olea europaea L.) by adsorption on silk fibroin. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 62, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhaoui, N.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; León, L.; de la Rosa, R.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Determination of phenolic compounds of “Sikitita” olive leaves by HPLC-DAD-TOF-MS. Comparison with its parents “Arbequina” and “Picual” olive leaves. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 58, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karioti, A.; Chatzopoulou, A.; Bilia, A.R.; Liakopoulos, G.; Stavrianakou, S.; Skaltsa, H. Novel secoiridoid glucosides in Olea europaea leaves suffering from boron deficiency. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 1898–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taamalli, A.; Arráez-Román, D.; Ibañez, E.; Zarrouk, M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction for the characterization of olive leaf phenolic compounds by using HPLC-ESI-TOF-MS/IT-MS(2). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japón-Luján, R.; Luque-Rodríguez, J.M.; de Castro, M.D. Multivariate optimisation of the microwave-assisted extraction of oleuropein and related biophenols from olive leaves. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 385, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahin, S.; Samlı, R. Optimization of olive leaf extract obtained by ultrasound-assisted extraction with response surface methodology. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013, 20, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japón-Luján, R.; Luque-Rodríguez, J.M.; de Castro, M.D. Dynamic ultrasound-assisted extraction of oleuropein and related biophenols from olive leaves. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1108, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taamalli, A.; Arráez-Román, D.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Ruiz-Torres, V.; Pérez-Sánchez, A.; Herrero, M.; Ibañez, E.; Micol, V.; Zarrouk, M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; et al. Use of advanced techniques for the extraction of phenolic compounds from Tunisian olive leaves: Phenolic composition and cytotoxicity against human breast cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xynos, N.; Papaefstathiou, G.; Psychis, M.; Argyropoulou, A.; Aligiannis, N.; Skaltsounis, A.-L. Development of a green extraction procedure with super/subcritical fluids to produce extracts enriched in oleuropein from olive leaves. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 67, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirantes-Piné, R.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Herrero, M.; Ibáñez, E.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS as a Powerful Analytical Tool for Characterising Phenolic Compounds in Olive-leaf Extracts. Phytochem. Anal. 2013, 24, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xynos, N.; Papaefstathiou, G.; Gikas, E.; Argyropoulou, A.; Aligiannis, N.; Skaltsounis, A.-L. Design optimization study of the extraction of olive leaves performed with pressurized liquid extraction using response surface methodology. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2014, 122, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japón-Luján, R.; de Castro, M.D. Superheated liquid extraction of oleuropein and related biophenols from olive leaves. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1136, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taamalli, A.; Arráez-Román, D.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Ruiz-Torres, V.; Pérez-Sánchez, A.; Herrero, M.; Ibañez, E.; Micol, V.; Zarrouk, M.; Segura-Carretero, A.; et al. Use of advanced techniques for the extraction of phenolic compounds from Tunisian olive leaves: Phenolic composition and cytotoxicity against human breast cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, M.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibanez, E. Sub- and supercritical fluid extraction of functional ingredients from different natural sources: Plants, food-by-products, algae and microalgae: A review. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, R.; Harwood, J. Manual del Aceite de Oliva; Aparicio, R., Harwood, J., Eds.; Mundi-Prensa: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ranalli, A.; Lucera, L.; Contento, S.; Simone, N.; del Re, P. Bioactive constituents, flavors and aromas of virgin oils obtained by processing olives with a natural enzyme extract. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2004, 106, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, M.; Fki, I.; Jemai, H.; Ayadi, M.; Sayadi, S. Effect of storage on refined and husk olive oils composition: Stabilization by addition of natural antioxidants from Chemlali olive leaves. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrooyen, P.M.; van der Meer, R.; de Kruif, C.G. Microencapsulation: Its application in nutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2001, 60, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourtzinos, I.; Salta, F.; Yannakopoulou, K.; Chiou, A.; Karathanos, V.T. Encapsulation of Olive Leaf Extract in Becyclodextrin. J. Agric.Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8088–8094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abaza, L.; Taamalli, A.; Nsir, H.; Zarrouk, M. Olive Tree (Olea europeae L.) Leaves: Importance and Advances in the Analysis of Phenolic Compounds. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 682-698. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4040682

Abaza L, Taamalli A, Nsir H, Zarrouk M. Olive Tree (Olea europeae L.) Leaves: Importance and Advances in the Analysis of Phenolic Compounds. Antioxidants. 2015; 4(4):682-698. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4040682

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbaza, Leila, Amani Taamalli, Houda Nsir, and Mokhtar Zarrouk. 2015. "Olive Tree (Olea europeae L.) Leaves: Importance and Advances in the Analysis of Phenolic Compounds" Antioxidants 4, no. 4: 682-698. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4040682

APA StyleAbaza, L., Taamalli, A., Nsir, H., & Zarrouk, M. (2015). Olive Tree (Olea europeae L.) Leaves: Importance and Advances in the Analysis of Phenolic Compounds. Antioxidants, 4(4), 682-698. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox4040682