Bioactive Components of Parthenocissus quinquefolia with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

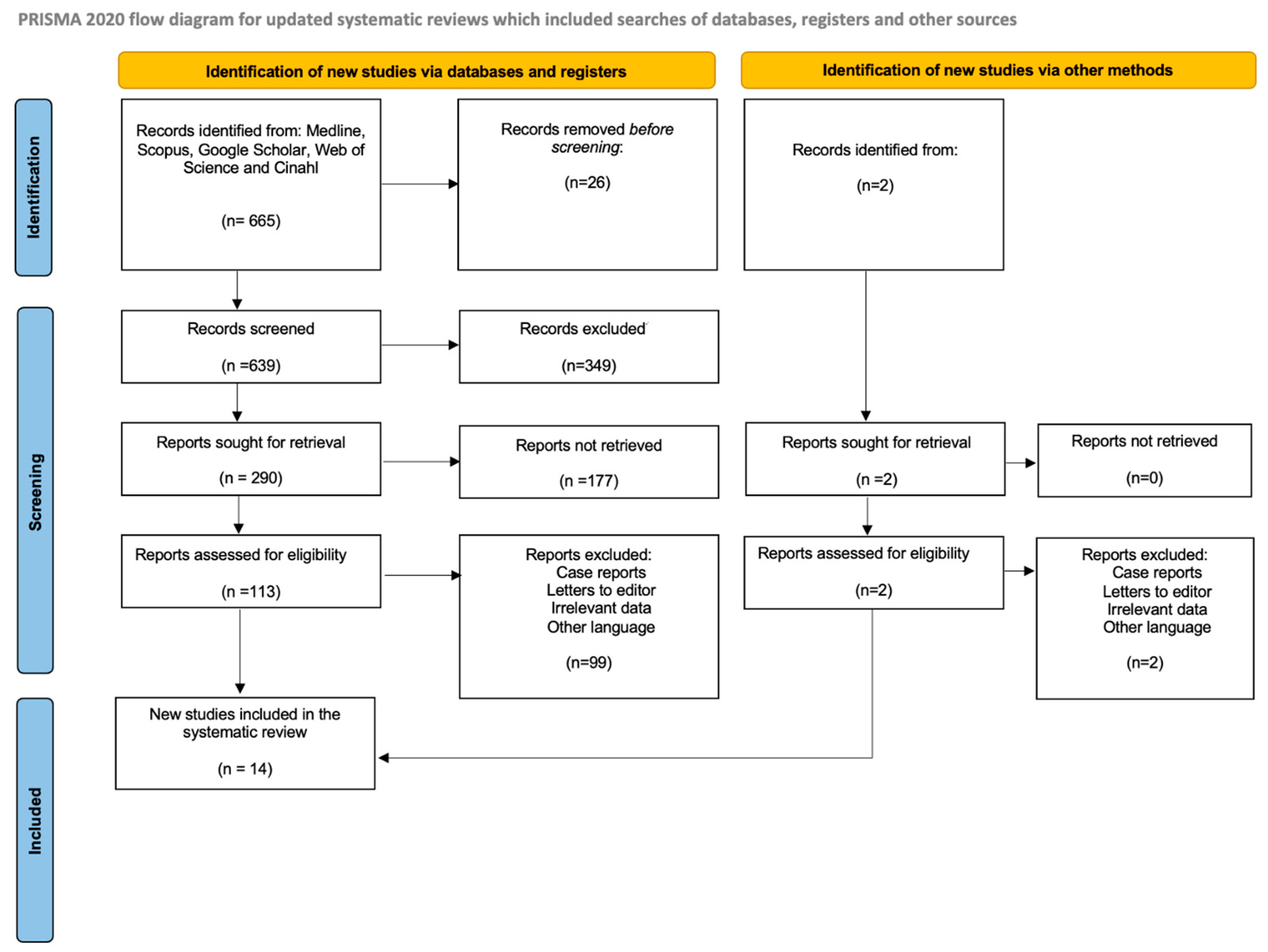

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method Designs

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Information Source and Search Strategies

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Methodological Quality Assessment

3. Results

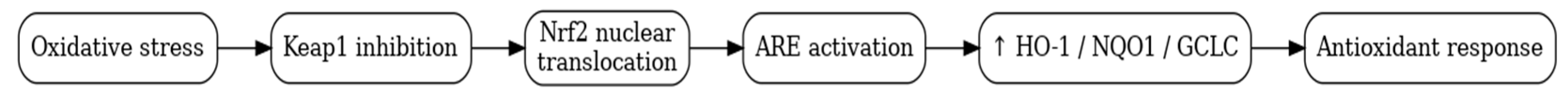

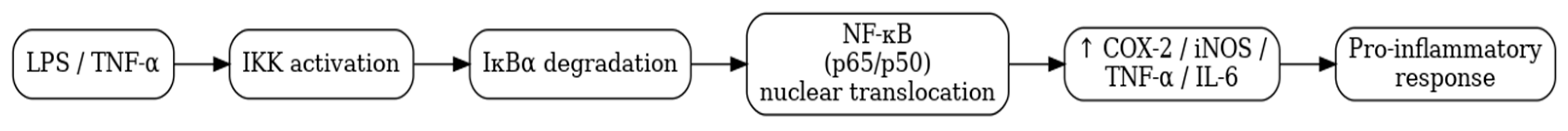

4. Discussion

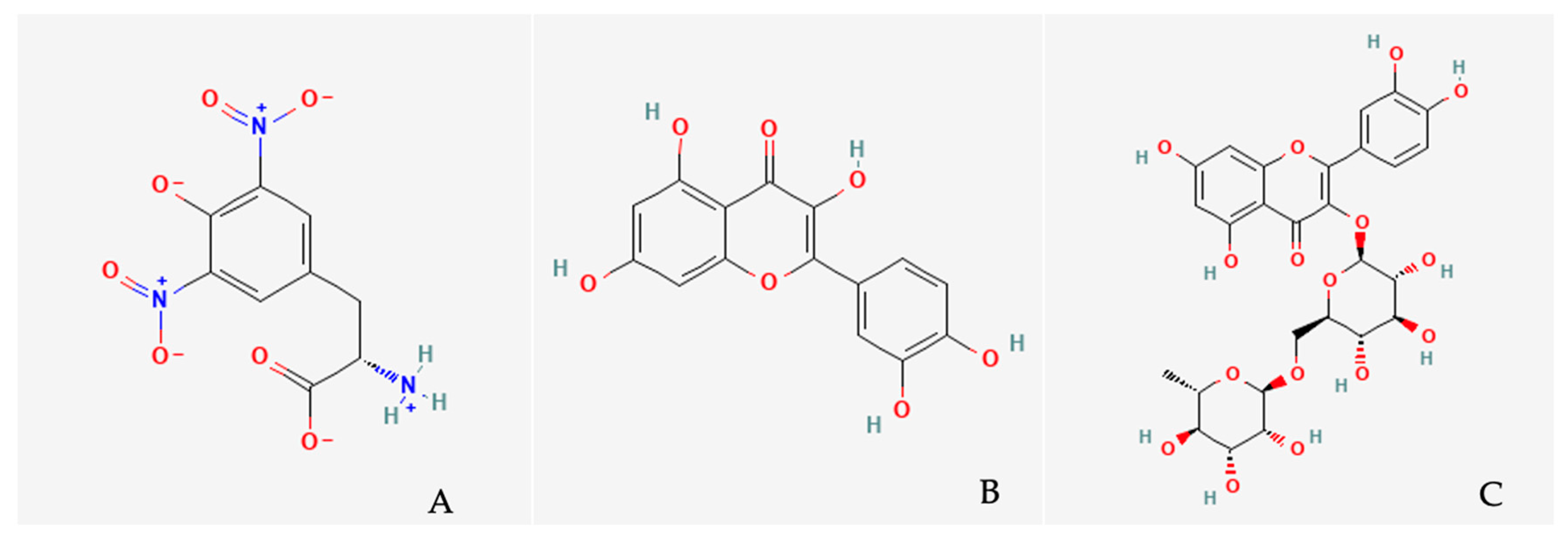

4.1. Phytochemical Profile of Parthenocissus quinquefolia

4.1.1. Flavonoids

4.1.2. Stilbenoids

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA | Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses |

| OSF | Open science framework |

| PCs | Phenolic compounds |

| N | Nitrogen |

| S | Sulphur |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| SAA | Serum amyloid A |

| ORAC | Oxygen radical absorbance capacity |

| AP-1 | Activator protein 1 |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 |

| MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor heat domain-associated protein 3 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HSV | Herpes simplex virus |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| NASH | Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinas |

| RCS | Reactive chlorine species |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin-1 |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| CLA | Conjugated linoleic acid |

| ARE | Antioxidant response element |

References

- Blinkova, O.; Makarenko, N.; Raichuk, L.; Havrylnuk, Y.; Grabovska, T.; Roubik, H. Invasion of Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch in the forest-steppe of Ukraine. Ecol. Quest. 2022, 34, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasoanto, M. Parthenocissus quinquefolia. In Fire Effects Information System; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. Available online: https://www.fdacs.gov/Agriculture-Industry/Plants-and-Nurseries (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Salazar, L.A.; Delporte, C.; Barra, G.V.; Cazar Ramirez, M.E.; López, M.D.; Ramírez-Alarcón, K.; Cruz-Martins, N.; et al. Ethnopharmacology, Phytochemistry and Biological Activities of Native Chilean Plants. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro, S. Antioxidant activity and phytoactive compounds related to biological effects present in native southern Chilean plants: A review. J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2025, 69, 6115–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.K. Wildland S1hrubs of the United States and Its Territories; USDA: San Juan, PR, USA, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 542–544. Available online: https://www.fdacs.gov/Divisions-Offices/Florida-Forest-Service (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Zardi-Bergaouia, A.; Jouinia, M.; Znatia, M.; El Ayeb-Zakhamab, A.; Janneta, H.B. Physico-chemical properties, composition and antioxidant activity of seed oil from the Tunisian Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) planch). J. Tunis. Chem. Soc. 2016, 18, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z.; Faisal, S.; Anjum, P.; Sardar, A.A.; Siddiqui, S.Z. Phytochemical properties and antioxidant activities of leaves and fruits extracts of Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch. Bangladesh J. Bot. 2018, 47, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Frase, D.M.; Bannon, S. Contact Dermatitis From Exposure to Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia): A Deviation From the Saying “Leaves of Three, Let It Be”. Cureus 2025, 17, e86240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, S.; Kunaparaju, N.; Zito, S.W.; Barletta, M.A. Effect of Wrightia tinctoria and Parthenocissus quinquefolia on blood glucose and insulin levels in the Zucker diabetic rat model. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2011, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Perveen, A.; Khan, Z.U.; Sardar, A.A.; Shaheen, S.; Manzoor, A. Phytochemical screening and antioxidant potential of Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) planch extracts of bark and stem. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 31, 1813–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Cömert Önder, F.; Kalın, S.; Maraba, Ö.; Önder, A.; Ilgın, P.; Karabacak, E. Anticancer, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial Activities, and HPLC Analysis of Alcoholic Extracts of Parthenocissus quinquefolia L. Plant Collected from Çanakkale. J. Adv. Res. Nat. Appl. Sci. 2024, 10, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, S.; Drakou, E.G.; Hickler, T.; Thines, M.; Nogues-Bravo, D. Evaluating natural medicinal resources and their exposure to global change. Lancet Planet Health 2023, 7, e155–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagare, S.; Bhatia, M.; Tripathi, N.; Pagare, S.; Bansal, Y.K. Secondary metabolites of plants and their role: Overview. Curr. Trends Biotechnol. Pharm. 2015, 9, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I.; Mohamed, A.A. A Comprehensive Review on the Biological, Agricultural and Pharmaceutical Properties of Secondary Metabolites Based-Plant Origin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrosch, C.; Zotchev, S.B. Production of bioactive plant secondary metabolites through in vitro technologies—Status and outlook. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 6649–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, P.; Huang, H. Inflammation and aging: Signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchi, S.; Guilbaud, E.; Tait, S.W.G.; Yamazaki, T.; Galluzzi, L. Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tsao, R. Dietary polyphenols, oxidative stress and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Singh, R.B.; Buttar, H.S.; Wilson, D.; De Meester, F. Food Antioxidants and Their Anti-Inflammatory Properties: A Potential Role in Cardiovascular Diseases and Cancer Prevention. Diseases 2016, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sadowski, A.; Zielińska-Bliźniewska, H.; Zajdel, K.; Zajdel, R. Network Pharmacology as a Tool to Investigate the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Plant Secondary Metabolites-A Review and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Mariateresa, O.; Giulio, T.; Mariateresa, R. Oxidative Stress: The Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals in the Prevention and Treatment of Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 29, 372:n71. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.; Linuma, M.; Murata, H. Stilbene derivates in the stem of Parthenocissus quinquefolia. Phytochemistry 1998, 48, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.B.; Wang, A.G.; Ji, T.F.; Su, Y.L. Two new oligostilbenes from the stem of Parthenocissus quinquefolia. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 16, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattanata, N.; Sakda, D.; Suthep, P.; Wandee, B.; Bundit, P.; Ratree, T.; Phangthip, U.; Parcharee, B.; Jureerut, D. Antioxidant and antibacterial properties of selected Thai weed extracts. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh-Omraj, S. Preliminary phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch. Int. J. Life Sci. 2017, 8, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Salah, M.M.; El-Dein, M.M.Z.; EL-Hefny, M.; Ali, H.M.; Farraj, D.A.A.; Hatamleh, A.A.; Salem, M.Z.M.; Ashmawy, N.A. Ecofriendly Bioagents, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, and Plectranthus neochilus Extracts to Control the Early Blight Pathogen (Alternaria solani) in Tomato. Agronomy 2021, 11, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ticha, M.; Meksi, N.; Attia, H.E.; Haddar, W.; Guesmi, A.; Ben Jannet, H.; Mhenni, M.F. Ultrasonic extraction of Parthenocissus quinquefolia colorants: Extract identification by HPLC-MS analysis and cleaner application on the phytodyeing of natural fibres. Dye. Pigment. 2017, 141, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhynia, L.; Yemelianova, O. Anatomical and phytochemical study leaves of Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch. Phytother. J. 2023, 3, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konovalova, O.; Yashchuk, B.; Hurtovenko, I.; Shcherbakova, O.; Kalista, M.; Sydora, N. Study on content of flavonoids and antioxidant activity of the raw materials of Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch. Sci. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 6, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rónavári, A.; Balázs, M.; Szilágyi, Á.; Molnár, C.; Kotormán, M.; Ilisz, I.; Kiricsi, M.; Kónya, Z. Multi-round recycling of green waste for the production of iron nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and prospects in remediation. Discov. Nano 2023, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Yang, C.Q.; Wei, Y.K.; Ma, Q.X.; Yang, L.; Chen, X.Y. Genomics grand for diversified plant secondary metabolites. Plant Div. Res. 2011, 33, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Verpoorte, R.; Alfermann, A.W. Metabolic Engineering of Plant Secondary Metabolism; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–23. Available online: https://www.uv.mx/personal/tcarmona/files/2019/02/Verpoorte-y-Alfermann-2000.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and biochemistry of dietary polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, B.R.; Heleno, S.A.; Oliveira, M.B.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C. Phenolic compounds: Current industrial aplications, limitations and future challenges. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneton, J. Farmacognosia: Fitoquímica y Plantas Medicinales, 2nd ed.; Editorial ACRIBIA: Madrid, España, 1993; pp. 305–341. Available online: https://tejadarossi.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/farmacognosia_bruneton.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Lim, I.; Ha, J. Biosynthetic Pathway of Proanthocyanidins in Major Cash Crops. Plants 2021, 10, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47, Erratum in J. Nutr. Sci. 2025, 14, e11. https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2024.73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Green tea catechins, caffeine and body-weight regulation. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 100, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.S.; Touyama, M.; Hisada, T.; Benno, Y. Effects of green tea consumption on human fecal microbiota with special reference to Bifidobacterium species. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012, 56, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, J.P.J.; Deavours, B.; Dixon, R.A.; Ferreira, D. The Stereochemistry of Flavonoids. In The Science of Flavonoids; Grotewold, E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–46. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-0-387-28822-2_1 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Anitha, S.; Krishnan, S.; Senthilkumar, K.; Sasirekha, V. Theoretical investigation on the structure and antioxidant activity of (+) catechin and (−) epicatechin—A comparative study. Mol. Phys. 2020, 118, e1745917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J.; Elbaz, H.A.; Lee, I.; Zielske, S.P.; Malek, M.H.; Hüttemann, M. Mechanism and Therapeutic Effects of (-) Epicatechin and Other Polyphenols in Cancer, Inflammation, Diabetes, and Neurodegeneration. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 181260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Sanchez, I.; Maya, L.; Ceballos, G.; Villarreal, F. (-)-epicatechin activation of endothelial cell endothelial nitric oxide synthase, nitric oxide, and related signaling pathways. Hypertension 2010, 55, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Suzuki, K. The Effects of Flavonoids on Skeletal Muscle Mass, Muscle Function, and Physical Performance in Individuals with Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.J.; Liu, S.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Hsu, S.H.; Chang, Y.P.; Lin, J.T. Three Pathways Assess Anti-Inflammatory Response of Epicatechin with Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Macrophage RAW264.7 Cells. J. Food Biochem. 2015, 39, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Prieto, M.A.; Bettaieb, A.; Haj, F.G.; Fraga, C.G.; Oteiza, P.I. (-)-Epicatechin prevents TNFα-induced activation of signaling cascades involved in inflammation and insulin sensitivity in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 527, 113–118, Erratum in Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 756, 109992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeter, H.; Heiss, C.; Balzer, J.; Kleinbongard, P.; Keen, C.L.; Hollenberg, N.K.; Sies, H.; Kwik-Uribe, C.; Schmitz, H.H.; Kelm, M. (-)-Epicatechin mediates beneficial effects of flavanol-rich cocoa on vascular function in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, M.; van der Heijden, R.; Heeringa, P.; Kaijzel, E.; Verschuren, L.; Blomhoff, R.; Kooistra, T.; Kleemann, R. Epicatechin attenuates atherosclerosis and exerts anti-inflammatory effects on diet-induced human-CRP and NFκB in vivo. Atherosclerosis 2014, 233, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Miyazawa, T. Absorption and distribution of tea catechin, (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, in the rat. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 1997, 43, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, B.; Higdon, J.V. Antioxidant activity of tea polyphenols in vivo: Evidence from animal studies. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3275S–3284S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Pakozdi, A.; Koch, A.E. Regulation of interleukin-1beta-induced chemokine production and matrix metalloproteinase 2 activation by epigallocatechin-3-gallate in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 2393–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.E.; Yang, G.; Park, Y.B.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, Y.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Prevents Acute Gout by Suppressing NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Mitochondrial DNA Synthesis. Molecules 2019, 24, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges Geagea, A.; Rizzo, M.; Eid, A.; Hajj Hussein, I.; Zgheib, Z.; Zeenny, M.N.; Jurjus, R.; Uzzo, M.L.; Spatola, G.F.; Bonaventura, G.; et al. Tea catechins induce crosstalk between signaling pathways and stabilize mast cells in ulcerative colitis. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 865–877. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Cheng, K.; Niu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, X. (-)-Epicatechin gallate prevents inflammatory response in hypoxia-activated microglia and cerebral edema by inhibiting NF-κB signaling. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 729, 109393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cao, Z.-R. Anti-inflammatory Effects of (-)-Epicatechin in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Raw 264.7 Macrophages. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 13, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, A.W.; Haenen, G.R.; Bast, A. Health effects of quercetin: From antioxidant to nutraceutical. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 585, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.A.; Mahmood, S.; Hilles, A.R.; Ali, A.; Khan, M.Z.; Zaidi, S.A.A.; Iqbal, Z.; Ge, Y. Quercetin as a Therapeutic Product: Evaluation of Its Pharmacological Action and Clinical Applications—A Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazvinšćak Jembrek, M.; Oršolić, N.; Mandić, L.; Sadžak, A.; Šegota, S. Anti-Oxidative, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Apoptotic Effects of Flavonols: Targeting Nrf2, NF-κB and p53 Pathways in Neurodegeneration. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.C.; Huang, W.C.S.; Pang, J.H.; Wu, Y.H.; Cheng, C.Y. Quercetin Inhibits the Production of IL-1β-Induced Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines in ARPE-19 Cells via the MAPK and NF-κB Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Martinez, E.J.; Flores-Hernández, F.Y.; Salazar-Montes, A.M.; Nario-Chaidez, H.F.; Hernández-Ortega, L.D. Quercetin, a Flavonoid with Great Pharmacological Capacity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.H.; Park, H.J.; Jung, H.Y.; Kang, I.K.; Kim, B.O.; Cho, Y.J. Isoquercitrin isolated from newly bred Green ball apple peel in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophage regulates NF-κB inflammatory pathways and cytokines. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, M.; Yang, T.; Deng, Y.; Ding, Y.; Guo, T.; Shang, J. Isoquercitrin Attenuates Steatohepatitis by Inhibition of the Activated NLRP3 Inflammasome through HSP90. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullón, B.; Lú-Chau, T.A.; Moreira, M.T.; Lema, J.M.; Eibes, G. Rutin: A review on extraction, identification and purification methods, biological activities and approaches to enhance its bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Liu, X.; Chang, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, M.; Liu, M. Rutin prevents inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide in RAW 264.7 cells via conquering the TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6-NF-κB signalling pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.H.; Yang, J.J.; Yang, M.L.; Li, Y.C.; Kuan, Y.H. Rutin decreases lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via inhibition of oxidative stress and the MAPK-NF-κB pathway. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 69, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Maoqiang, L.; Fan, H.; Zhenyu, B.; Qifang, H.; Xuepeng, W.; Liulong, Z. Rutin attenuates neuroinflammation in spinal cord injury rats. J. Surg. Res. 2016, 203, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, T.; Rotelli, A.E.; Juarez, A.O.; Pelzer, L.E. Anti-inflammatory properties of plant flavonoids. Effects of rutin, quercetin and hesperidin on adjuvant arthritis in rat. Farmaco 2001, 56, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semwal, D.K.; Semwal, R.B.; Combrinck, S.; Viljoen, A. Myricetin: A Dietary Molecule with Diverse Biological Activities. Nutrients 2016, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Sofic, E.; Prior, R.L. Antioxidant and prooxidant behavior of flavonoids: Structure-activity relationships. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1997, 22, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Hu, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhao, Q.; Tao, X.; Ding, B.; Chen, S.; Zhu, J.; Guo, X.; Lin, Z. Myricetin attenuates hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in neonatal rats via NRF2 signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1134464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, M.; Saeed, F.; Hussain, G.; Imran, A.; Mehmood, Z.; Gondal, T.A.; El-Ghorab, A.; Ahmad, I.; Pezzani, R.; Arshad, M.U.; et al. Myricetin: A comprehensive review on its biological potentials. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 5854–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabrauskiene, J.; Kopustinskiene, D.M.; Lazauskas, R.; Bernatoniene, J. Naringin and Naringenin: Their Mechanisms of Action and the Potential Anticancer Activities. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, M.; Lin, X.; Zheng, X.; Qi, H.; Chen, J.; Zeng, X.; Bai, W.; Xiao, G. Biological Activities and Solubilization Methodologies of Naringin. Foods 2023, 12, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharti, S.; Rani, N.; Krishnamurthy, B.; Arya, D.S. Preclinical evidence for the pharmacological actions of naringin: A review. Planta Medica 2014, 80, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.P.; Abraham, A. Inhibition of LPS induced pro-inflammatory responses in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells by PVP-coated naringenin nanoparticle via down regulation of NF-κB/P38MAPK mediated stress signaling. Pharmacol. Rep. 2017, 69, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, S.; Tomizawa, A.; Ohtake, T.; Koiwai, K.; Ujibe, M.; Ishikawa, M. Naringenin-induced apoptosis via activation of NF-kappaB and necrosis involving the loss of ATP in human promyeloleukemia HL-60 cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 166, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Mo, Y.; Peng, H.; Gong, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Xie, J. Naringin ameliorates cognitive deficits in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2016, 19, 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, S.M.; Bok, S.H.; Jang, M.K.; Lee, M.K.; Nam, K.T.; Park, Y.B.; Rhee, S.J.; Choi, M.S. Antioxidative activity of naringin and lovastatin in high cholesterol-fed rabbits. Life Sci. 2001, 69, 2855–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lázaro, M. Distribution and biological activities of the flavonoid luteolin. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlocskó, R.B.; Mastyugin, M.; Török, B.; Török, M. Correlation of physicochemical properties with antioxidant activity in phenol and thiophenol analogues. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolt, A.; Cox, L.S. Structural basis of the anti-ageing effects of polyphenolics: Mitigation of oxidative stress. BMC Chem. 2020, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Shi, R.; Wang, X.; Shen, H.M. Luteolin, a flavonoid with potential for cancer prevention and therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2008, 8, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Peng, W.H.; Tsai, K.D.; Hsu, S.L. Luteolin suppresses inflammation-associated gene expression by blocking NF-kappaB and AP-1 activation pathway in mouse alveolar macrophages. Life Sci. 2007, 81, 1602–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.N.; Lee, Y.; Wu, D.; Pae, M. Luteolin inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation via blocking ASC oligomerization. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2021, 92, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kelley, K.W.; Johnson, R.W. Luteolin reduces IL-6 production in microglia by inhibiting JNK phosphorylation and activation of AP-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 7534–7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandurangan, A.K.; Dharmalingam, P.; Sadagopan, S.K.; Ganapasam, S. Luteolin inhibits matrix metalloproteinase 9 and 2 in azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, S.; Khedmati, M.; Yousef-Nejad, F.; Mahdavi, M. Medicinal chemistry perspective on the structure-activity relationship of stilbene derivatives. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 19823–19879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhou, D.; Li, N. Bioactive stilbenes from plants. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2022, 73, 265–403. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: The in vivo evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Resveratrol suppresses TNF-induced activation of nuclear transcription factors NF-kappa B, activator protein-1, and apoptosis: Potential role of reactive oxygen intermediates and lipid peroxidation. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 6509–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, J.K.; Surh, Y.J. Molecular basis of chemoprevention by resveratrol: NF-kappaB and AP-1 as potential targets. Mutat Res 2004, 555, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, J.K.; Shin, Y.K.; Kim, S.H.; Surh, Y.J. Resveratrol inhibits phorbol ester-induced expression of COX-2 and activation of NF-kappaB in mouse skin by blocking IkappaB kinase activity. Carcinogenesis 2006, 27, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarubbo, F.; Esteban, S.; Miralles, A.; Moranta, D. Effects of Resveratrol and other Polyphenols on Sirt1: Relevance to Brain Function During Aging. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2018, 16, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszar, A.; Labinskyy, N.; Podlutsky, A.; Kaminski, P.M.; Wolin, M.S.; Zhang, C.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Pacher, P.; Hu, F.; de Cabo, R.; et al. Vasoprotective effects of resveratrol and SIRT1: Attenuation of cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and proinflammatory phenotypic alterations. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H2721–H2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Jiang, L.; Wu, B.; Zhou, J.; Pan, Y.J. Two Novel Antioxidative Stilbene Tetramers from Parthenocissus laetevirens. Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Yao, C.S. Natural Oligostilbenes. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 2006, 33, 601–644. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Wu, B.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, L. Stilbene oligomers from Parthenocissus laetevirens: Isolation, biomimetic synthesis, absolute configuration, and implication of antioxidative defense system in the plant. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 5233–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Yang, J.; Wu, B.; Pan, Y.; Wan, H.; Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Wang, S. Neuroprotective effect of parthenocissin A, a natural antioxidant and free radical scavenger, in focal cerebral ischemia of rats. Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, S63–S70, Erratum in Phytother. Res. 2010, 24, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Xu, X.; Tao, Z.; Wang, X.J.; Pan, Y. Resveratrol dimers, nutritional components in grape wine, are selective ROS scavengers and weak Nrf2 activators. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danışman, B.; Ercan Kelek, S.; Aslan, M. Resveratrol in Neurodegeneration, in Neurodegenerative Diseases, and in the Redox Biology of the Mitochondria. Psychiatry Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 33, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.A.Q.; Silva, J.P.B.; Romeiro, C.F.R.; Dos Santos, S.M.; Rodrigues, C.A.; Gonçalves, P.R.; Sakai, J.T.; Mendes, P.F.S.; Varela, E.L.P.; Monteiro, M.C. Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Resveratrol in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of SIRT1. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 8152373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont, P.; Courtois, A.; Atgié, C.; Richard, T.; Krisa, S. In the shadow of resveratrol: Biological activities of epsilon-viniferin. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 78, 465–484, Erratum in J. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 78, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuloria, S.; Sekar, M.; Khattulanuar, F.S.; Gan, S.H.; Rani, N.N.I.M.; Ravi, S.; Subramaniyan, V.; Jeyabalan, S.; Begum, M.Y.; Chidam-baram, K.; et al. Chemistry, Biosynthesis and Pharmacology of Viniferin: Potential Resveratrol-Derived Molecules for New Drug Discovery, Devel-opment and Therapy. Molecules 2022, 27, 5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Billard, C.; Izard, J.C.; Roman, V.; Kern, C.; Mathiot, C.; Mentz, F.; Kolb, J.P. Comparative antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of resveratrol, epsilon-viniferin and vine-shots derived polyphenols (vineatrols) on chronic B lymphocytic leukemia cells and normal human lymphocytes. Leuk. Lymphoma 2002, 43, 1991–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, N.C.; Baek, S.J. The anticancer effects of resveratrol: Modulation of transcription factors. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdge, G.C.; Calder, P.C. Introduction to fatty acids and lipids. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 112, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ku, K.T.; Huang, Y.L.; Huang, Y.J.; Chiou, W.F. Miyabenol A inhibits LPS-induced NO production via IKK/IkappaB inactivation in RAW 264.7 macrophages: Possible involvement of the p38 and PI3K pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 8911–8918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, C.M. Microplate bioassay to examine the effects of grapevine-isolated stilbenoids on survival of root knot nema-todes. BMC Res. Notes. 2022, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morvaridzadeh, M.; Estêvão, M.D.; Morvaridi, M.; Belančić, A.; Mohammadi, S.; Hassani, M.; Heshmati, J.; Ziaei, S. The effect of Conjugated Linoleic Acid intake on oxidative stress parameters and antioxidant enzymes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2022, 163, 106666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Whang, K.Y.; Park, Y. Impact of Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) on Skeletal Muscle Metabolism. Lipids 2016, 51, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.K.; Calder, P.C. Omega-6 fatty acids and inflammation. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 132, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.D.; Maceyka, M.; Cowart, L.A.; Spiegel, S. Sphingolipids in metabolic disease: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2133–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ni, M.; Tian, Y.; Wang, H.; Qiu, J.; You, W.; Wei, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, F.; et al. Myeloid Nrf2 deficiency aggravates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis progression by regulating YAP-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome signaling. iScience 2021, 24, 102427, Erratum in iScience 2021, 24, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Halaka, D.; Shpaizer, A.; Zeigerman, H.; Kanner, J.; Tirosh, O. DMF-Activated Nrf2 Ameliorates Palmitic Acid Toxicity While Potentiates Ferroptosis Mediated Cell Death: Protective Role of the NO-Donor S-Nitroso-N-Acetylcysteine. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Li, J.Y.; Zeng, B.; Chen, G.L. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Signaling in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Alarcon, S.A.; Valenzuela, R.; Valenzuela, A.; Videla, L.A. Liver Protective Effects of Extra Virgin Olive Oil: Interaction between Its Chemical Composition and the Cell-signaling Pathways Involved in Protection. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord.-Drug Targets 2018, 18, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronat, A.; Serreli, G.; Rodríguez-Morató, J.; Deiana, M.; de la Torre, R. Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds’ Activity against Age-Associated Cognitive Decline: Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutunchi, H.; Ostadrahimi, A.; Saghafi-Asl, M. The Effects of Diets Enriched in Monounsaturated Oleic Acid on the Management and Prevention of Obesity: A Systematic Review of Human Intervention Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 864–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, A.; Ji, T.; Su, Y. Chemical constituents from Parthenocissus quinquefolia. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi 2010, 35, 1573–1576. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Keylor, M.H.; Matsuura, B.S.; Stephenson, C.R. Chemistry and Biology of Resveratrol-Derived Natural Products. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 8976–9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.T.; Long, P.T.; Hien, T.T.; Tuan, D.T.; An, N.T.T.; Khoi, N.M.; Van Oanh, H.; Hung, T.M. Anti-inflammatory effect of oligostilbenoids from Vitis heyneana in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages via suppressing the NF-κB activation. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waffo-Téguo, P.; Shaver, J.; Mérilon, J.M. Stilbenoid chemistry from wine and the genus Vitis, a review. OENO One 2012, 46, 57–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastamoulis, Y.; Bisson, J.; Temsamani, H.; Richard, T.; Marchal, A.; Mérillon, J.M.; Waffo-Téguo, P. New E-miyabenol isomer isolated from grapevine cane using centrifugal partition chromatography guided by mass spectrometry. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 3138–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lin, T.; Gao, Y.; Xu, J.; Jiang, C.; Wang, G.; Bu, G.; Xu, H.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.W. The resveratrol trimer miyabenol C inhibits β-secretase activity and β-amyloid generation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yao, J.; Han, C.; Yang, J.; Chaudhry, M.T.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Yin, Y. Quercetin, Inflammation and Immunity. Nutrients 2016, 8, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, F.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y. Catechins: Protective mechanism of antioxidant stress in atherosclerosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1144878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.; Kim, H.J.; Jin, C.; Lee, Y.S. Antioxidant caffeic acid derivatives from leaves of Parthenocissus tricuspidata. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2004, 27, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Montaño, J.M.; Burgos-Morón, E.; Pérez-Guerrero, C.; López-Lázaro, M. A review on the dietary flavonoid kaempferol. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 298–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Deng, W. Review on the adhesive tendrils of Parthenocissus. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.J.; Dave, Y.S. Morpho-Histogenic Studies on Tndrild of Vitaceae. Am. J. Bot. 1970, 57, 363–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, A.J.; Vaughn, K.C. Structural and immunocytochemical characterization of the adhesive tendril of Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia [L.] Planch.). Protoplasma 2008, 232, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrell, J.A.; Delucchi, G.; Cabanillas, P. Primera cita de Parthenocissus tricuspidata y nuevo registro de P. quinquefolia (Vitaceae) adventicias en la Argentina. Rev. Mus. Argent. Cienc. Nat. 2012, 14, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamineh, Y.; Ghiasvand, M.; Panahi-Alanagh, S.; Rastegarmand, P.; Zolghadri, S.; Stanek, A. A Narrative Review of Quercetin’s Role as a Bioactive Compound in Female Reproductive Disorders. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Plant Part Used | Extraction Method | Analytical Technique | Identified Compounds | Concentrations | Assay Conditions/Biological Assays |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanaka T., Inuma M. Murata H. (1998) [23] | Stems | Acetone + Methanol extracts | Phytochemistry/Chromatography | Parthenocissin A, Parthenocissin B | Not reported | Antioxidant activity (in vitro), qualitative |

| Kumar S. et al. (2011) [9] | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 250 mg/kg p.c. (oral) | Antidiabetic activity in Zucker rats |

| Yang J. et al. (2013) [24] | Stems | Ethanol extract | HPLC/Chromatography | Parthenocissin M, Parthenocissin N, Miyabenol C, ε-viniferin | Not reported | Hepatoprotective, antibacterial, antifungal assays (in vitro) |

| Rattanata N. et al. (2014) [25] | Leaves | Ethanol extract | Colorimetric assays | Total phenolics, flavonoids (non-specific) | TPC/FC values not stated in manuscript | Antioxidant (DPPH, ABTS), Antibacterial assays |

| Zardi-Bergaoui A. et al. (2016) [6] | Pods & seeds | Soxhlet extraction (hexane) | GC-MS | Linoleic acid, Palmitic acid, Oleic acid | % composition reported in original study (not provided in manuscript) | Antioxidant/Antiradical activity |

| Deshmukh-Omraj S. (2017) [26] | Roots | Crude extract | Qualitative phytochemical screening | Alkaloids, Flavonoids, Terpenoids, Steroids, Coumarins, Carbohydrates, Tannins | Not applicable (qualitative) | Antibacterial assays (in vitro) |

| Zaheer-Ud-Din K. et al. (2017) [7] | Leaves & fruits | Crude ethanolic extracts | Qualitative phytochemical screening | Terpenoids, Flavonoids, Saponins, Tannins, Alkaloids, Glycosides | Not applicable (qualitative) | Antioxidant assays (DPPH) |

| Faisal S. et al. (2018) [10] | Bark | Methanolic extract | Colorimetric assays | Total phenolics | TPC value not provided in manuscript | Free radical scavenging assays |

| Mohamed A. A. et al. (2021) [27] | Fruits | Ethanolic extract | HPLC | Rutin, Myricetin | Rutin: 1891.60 mg/100 g extract; Myricetin: 241.06 mg/100 g extract | Antimicrobial and fungicidal assays |

| Ticha et al. (2017) [28] | Fruits | Ultrasonic aqueous extraction | HPLC-MS | Anthocyanins: delphinidin, petunidin, cyanidin, malvidin, peonidin, pelargonidin | Not reported | No biological assays performed (phytodyeing application) |

| Makhynia L., Yemelianova O. (2023) [29] | Leaves (flowering & fruiting stages) | Not reported | Qualitative phytochemical screening | Phenols, Flavonoids, Polysaccharides, Saponins, Tannins, Catechins, Anthocyanins, Hydroxycinnamic acids | Not applicable | No biological assays performed |

| Konovalova O. et al. (2023) [30] | Leaves, shoots, fruits | Ethanol extract | HPLC | Rutin, Quercetin, Quercetin-3-β-glycoside, Naringin (leaves & shoots); Epicatechin, Catechin, Gallocatechin, Epicatechin gallate, Luteolin (fruit) | Not reported | Antioxidant assays (DPPH) |

| Rónavári A. et al. (2023) [31] | Leaves | Green extract for nanoparticle synthesis | HPLC (phenolics), LC-analysis | Total phenolics, sugars (fructose, glucose, sucrose, mannitol, citric acid) | Not reported | No biological assays performed |

| Önder FC. et al. (2024) [11] | Fruits & red leaves | Ethanol extract | HPLC | Total phenolic content (non-specific) | TPC reported in original study (not in manuscript) | Anticancer, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial assays |

| Study | Plant Part | Identified Compounds | Quantification | Bioassay Type | Biological Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanaka T. Inuma M., Murata H. (1998) [23] | Stems | Parthenocissins A, B | Not reported (structural identification only) | Antioxidant (in vitro) | Positive antioxidant activity |

| Kumar S. et al. (2011) [9] | Not specified | Not reported | Not reported | In vivo (Zucker diabetic rat model; Oral glucose tolerance; Insulin ELISA) | Positive antihyperglycemic effect |

| Yang J. et al. (2013) [24] | Stems | Parthenocissins M/N, Miyabenol C, ε-viniferin | Not reported | Chemopreventive, antibacterial, antifungal | Positive effects reported |

| Rattanata N. et al. (2014) [25] | Leaves | Total phenolics/flavonoids (nonspecific) | TPC/TFC not reported | Antioxidant (DPPH, ABTS), antibacterial | Positive activity |

| Zardi-Bergaoui A. et al. (2016) [6] | Pods and seeds | Linoleic, palmitic, oleic acids | inhibition DPPH 31.6–83.8% | Antioxidant/antiradical | Positive activity |

| Deshmukh-Omraj S. (2017) [26] | Roots | Various phytochemicals (qualitative) | Not applicable (qualitative) | Antibacterial | Positive activity |

| Ud-Din Khan Z. et al. (2017) [7] | Leaves & fruits | Terpenoids, flavonoids, etc. (qualitative) | Not applicable (qualitative) | Antioxidant (DPPH) | Positive activity |

| Faisal S. et al. (2018) [10] | Bark | Total phenolics | IC50 bark ~24.32 mg/mL; stem ~13.6 mg/mL | Antioxidant | Positive scavenging activity |

| Mohamed A. A. et al. (2021) [27] | Fruits | Rutin, Myricetin | Not reported | Antimicrobial/fungicidal | Positive activity |

| Ticha et al. (2017) [28] | Fruits | Anthocyanins (delphinidin, petunidin, cyanidin, etc.) | Not reported | Not evaluated | No bioactivity reported |

| Makhynia L., Yemelianova O. (2023) [29] | Leaves (2 stages) | Phenolics, flavonoids, etc. (qualitative) | Not applicable (qualitative) | Not evaluated | No bioactivity reported |

| Konovalova O. et al. (2023) [30] | Leaves/shoots/fruits | Rutin, quercetin, catechins, etc. | Not reported | Antioxidant (DPPH) | Positive activity |

| Rónavári A. et al. (2023) [31] | Leaves | Total phenolics & sugars | Not reported | Not evaluated | No bioactivity reported |

| Cömert Önder F. et al. (2024) [11] | Fruits & red leaves | Total phenolics | TPC reported in original study (Not in manuscript) | Anticancer, antioxidant, antimicrobial | Positive activity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Becerra, Á.; Soto, F.; Vallejos, A.; Millán, D.; Valenzuela-Fuenzalida, J.J.; Leon-Rojas, J.E.; Cortés, M.E. Bioactive Components of Parthenocissus quinquefolia with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020169

Becerra Á, Soto F, Vallejos A, Millán D, Valenzuela-Fuenzalida JJ, Leon-Rojas JE, Cortés ME. Bioactive Components of Parthenocissus quinquefolia with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(2):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020169

Chicago/Turabian StyleBecerra, Álvaro, Felipe Soto, Alejandro Vallejos, Daniela Millán, Juan José Valenzuela-Fuenzalida, Jose E. Leon-Rojas, and Manuel E. Cortés. 2026. "Bioactive Components of Parthenocissus quinquefolia with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties: A Systematic Review" Antioxidants 15, no. 2: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020169

APA StyleBecerra, Á., Soto, F., Vallejos, A., Millán, D., Valenzuela-Fuenzalida, J. J., Leon-Rojas, J. E., & Cortés, M. E. (2026). Bioactive Components of Parthenocissus quinquefolia with Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants, 15(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020169