Targeting Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis: Oleanolic Acid and Its Molecular Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

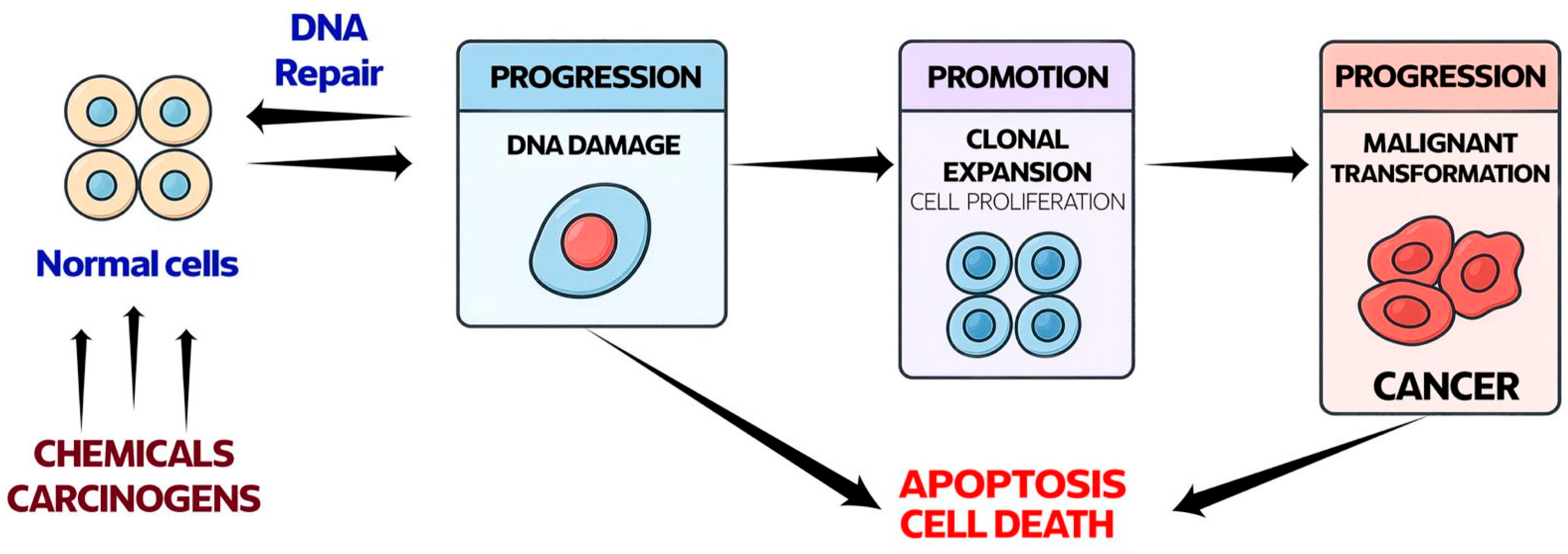

2. Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis

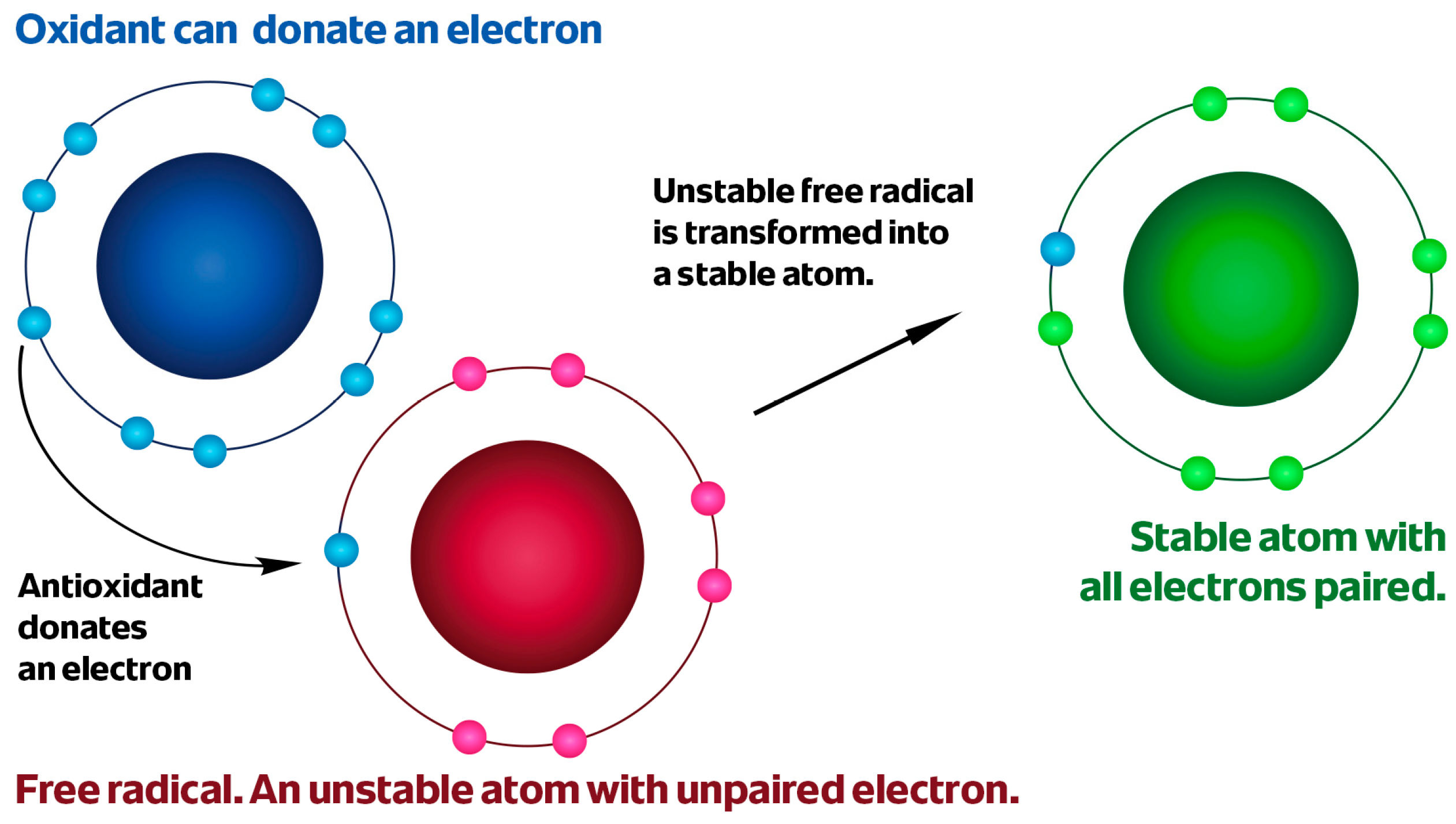

2.1. Oxidative Eustress in Cancerogenesis

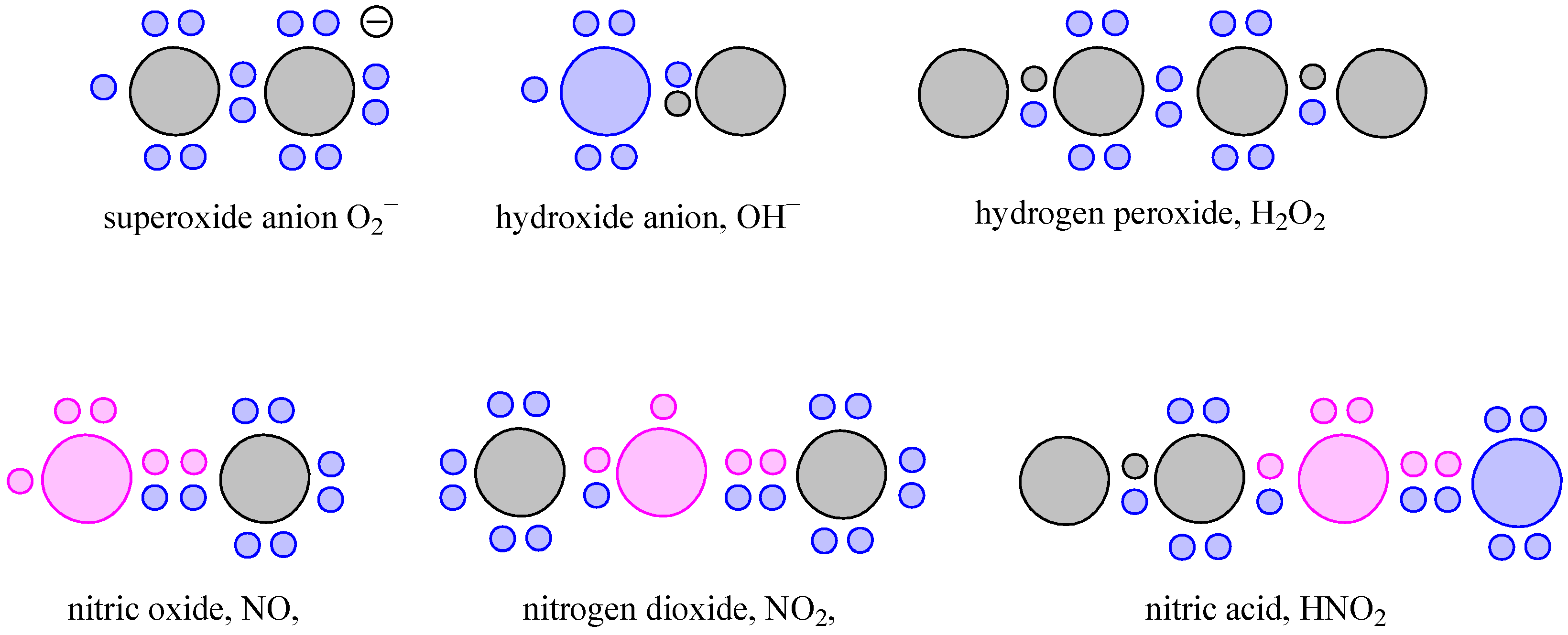

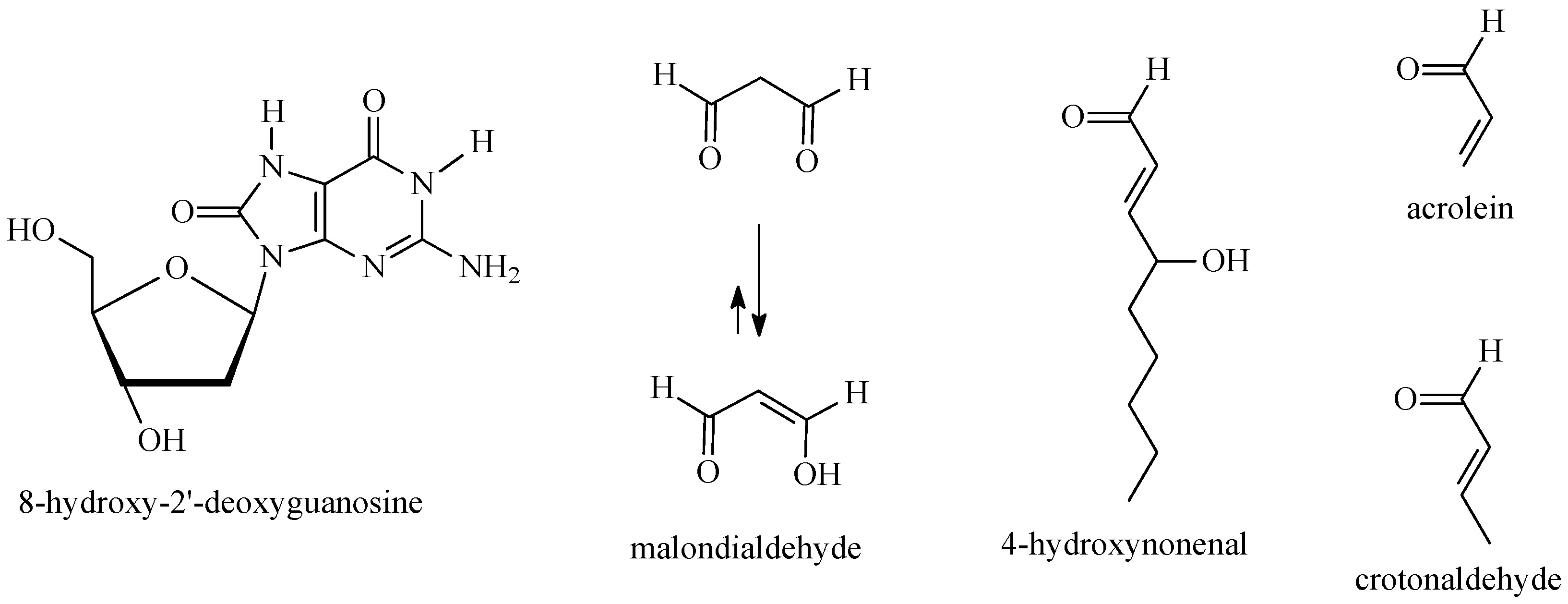

2.2. DNA Damage and Deregulation of Signaling Pathways by ROS/NOS

3. Physicochemical Profile and Natural Sources of Oleanolic Acid

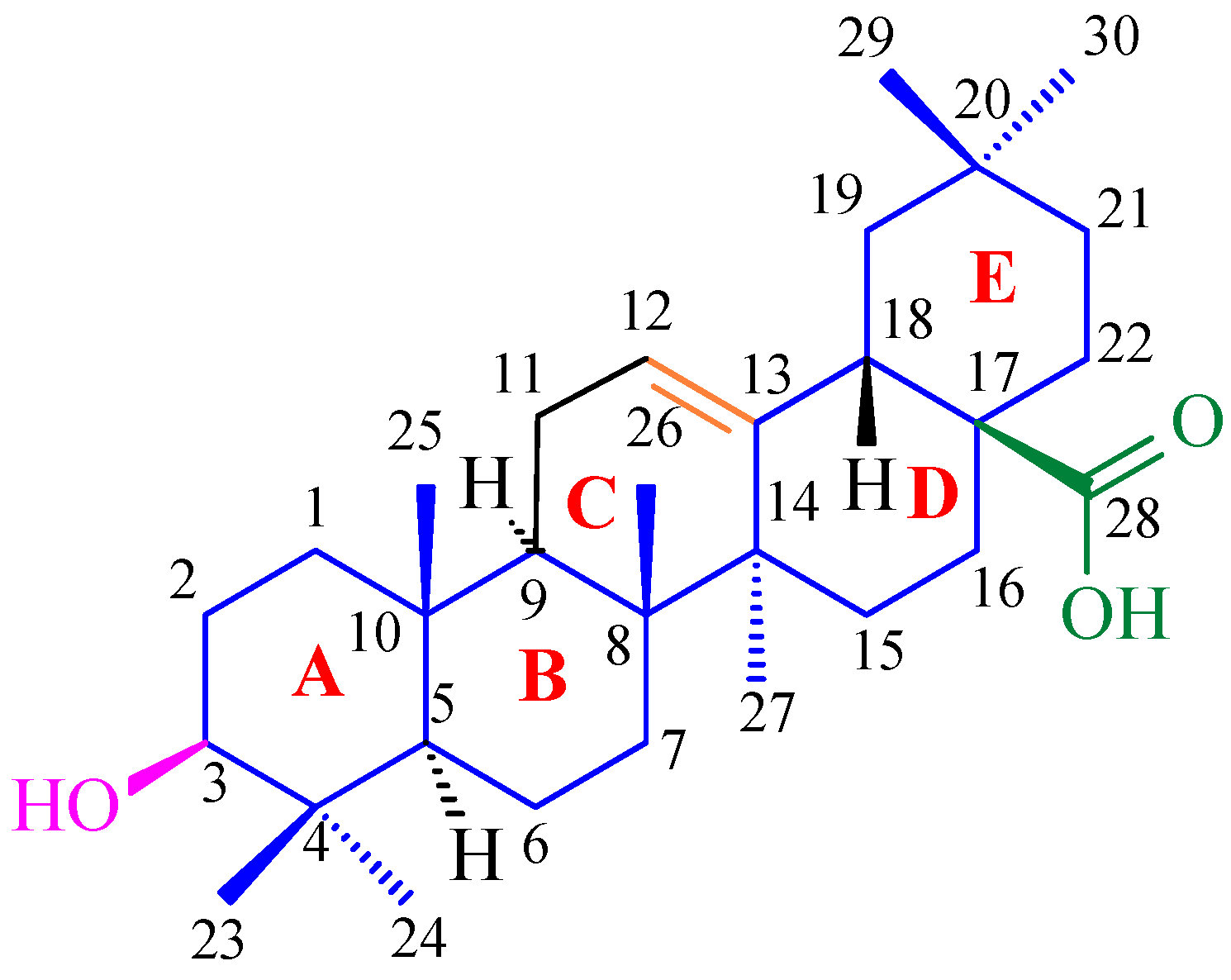

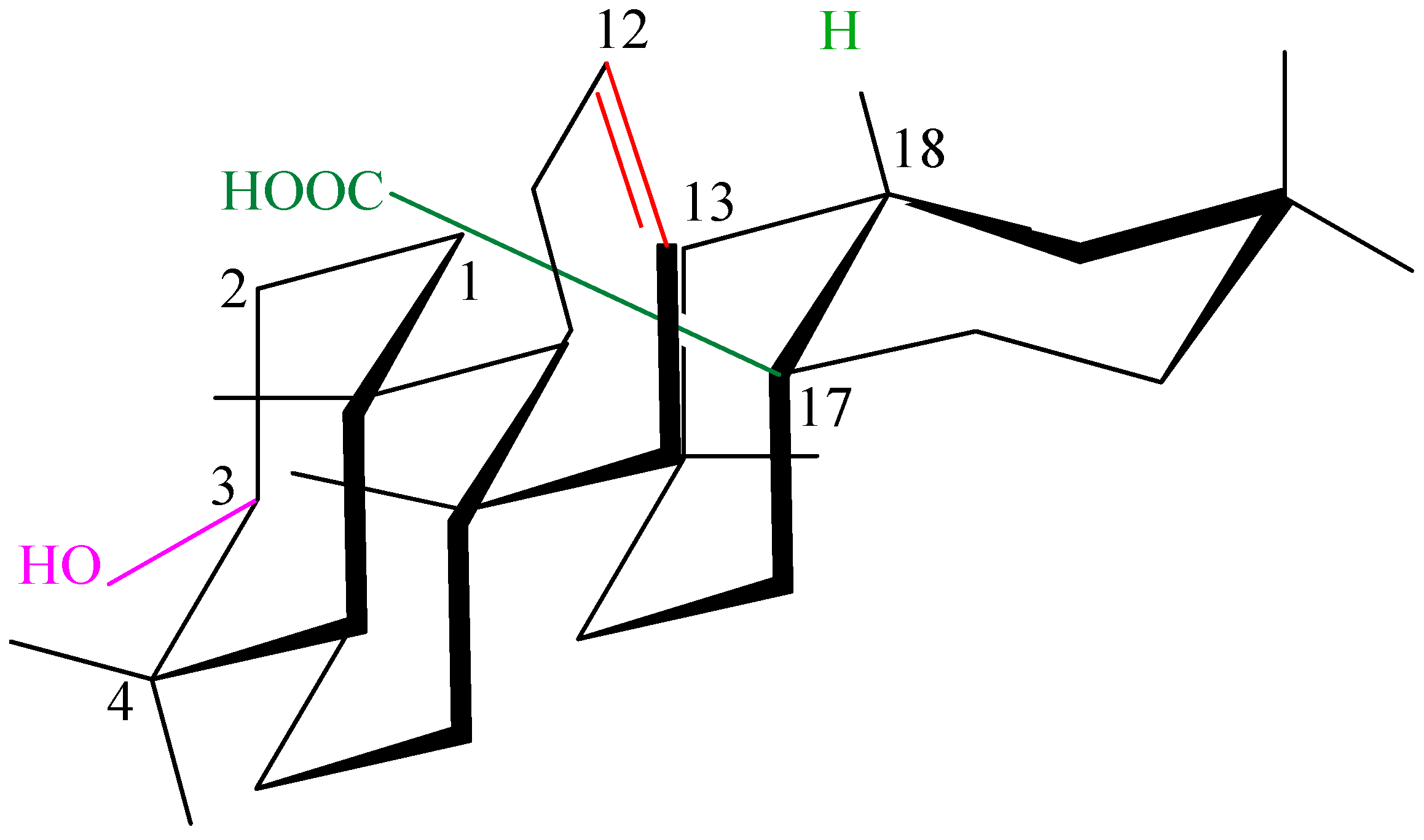

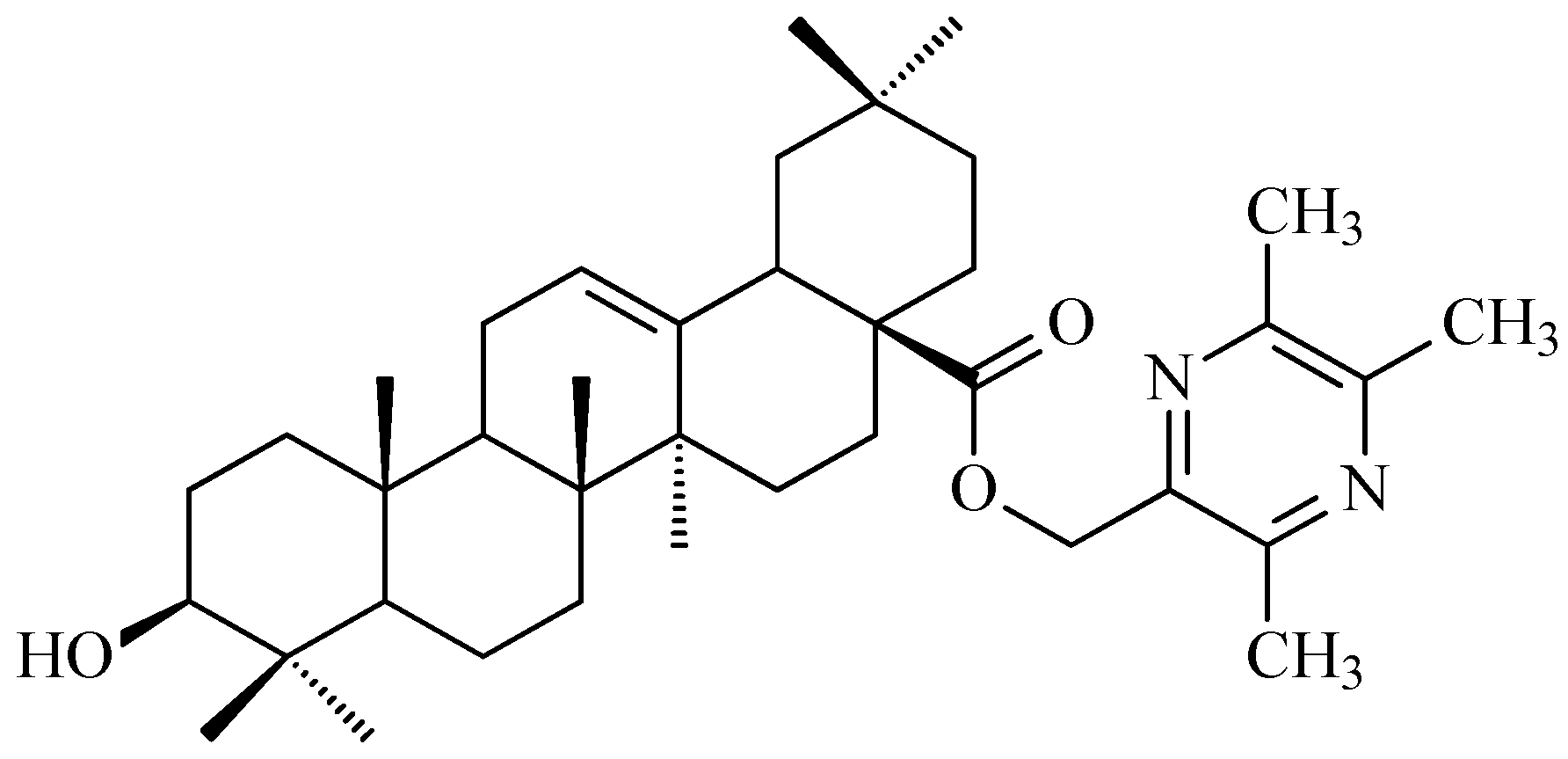

3.1. Structure and Stereochemistry of Oleanolic Acid

3.2. Endogenous Occurrence and Major Plant Sources

4. Key Antioxidant Mechanisms of Oleanolic Acid

4.1. Direct Scavenging of Free Radicals (OH•, O2•−, 1O2)

4.2. Activation of Endogenous Antioxidant Systems

4.3. Stabilization of Cell Membranes and Inhibition of Lipid Peroxidation

4.4. Chelation of Transition Metal Ions

| OA Concentration | Activity | Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mg/mL (0.1%) in DMSO | Free radical-scavenging activity (DPPH) | 2.9% | [64] |

| Hydroxy radical-scavenging activity | 33.4% | [64] | |

| Superoxide anion radical-scavenging activity | 26.3% | [64] | |

| Inhibition of lipid peroxidation in rat liver microsomes induced by vitamin C/Fe2+ | 10.7% | [64] | |

| Inhibition of lipid peroxidation in rat liver microsomes induced by CHP | 17.0% | [64] | |

| Inhibition of lipid peroxidation in rat liver microsomes induced by CCl4/NADPH | 17.0% | [64] | |

| 10 μg/mL (0.001%) in methanol | Superoxide anion radical-scavenging activity | 30.25% | [68] |

| Hydroxy radical-scavenging activity | 25.45% | [68] | |

| Nitric oxide radical scavenging | 11.15% | [68] |

4.5. Inhibition of Pro-Oxidant and Pro-Inflammatory Enzymes

4.6. Downregulation of NF-κB and MAPK

4.7. Other Mechanisms—Mitochondrial Protection, HO-1 Induction

5. Interconnection with Carcinogenesis Pathways

5.1. ROS-Mediated DNA Damage and Mutagenesis as Drivers of Tumor Initiation

5.2. Suppression of Oxidative Inflammation and Modulation of Transcription Factors Relevant to Cancer Progression

5.3. Crosstalk Between Antioxidant Signaling and Oncogenic Pathways (e.g., NF-κB vs. Nrf2 Balance)

6. Anticancer Mechanisms Mediated by Oxidative Stress Modulation

6.1. OA-Induced Apoptosis (via Caspases, BAX/BCL-2 Signaling)

6.2. Autophagy Regulation, Cell Cycle Arrest, and Anti-Proliferative Effects via PI3K/AKT/mTOR, AKT/JNK Pathways

6.3. Anti-Angiogenic, Anti-Migration, Anti-Metastatic Properties Linked to Oxidative Microenvironment Modulation

6.4. Cancer Stemness Reduction and Chemosensitization of Oleanolic Acid (e.g., Reversing 5-FU Resistance in Colorectal Models)

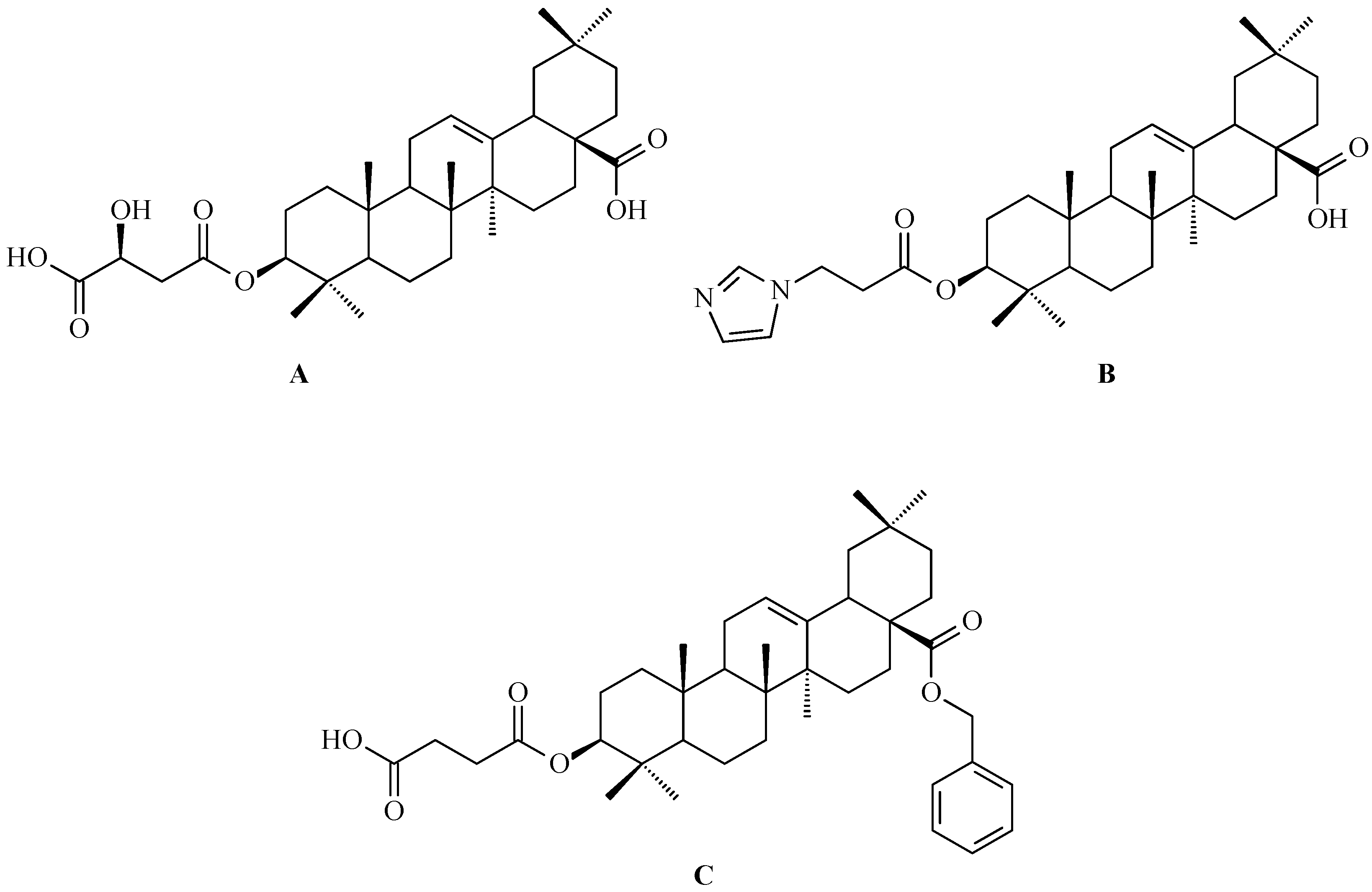

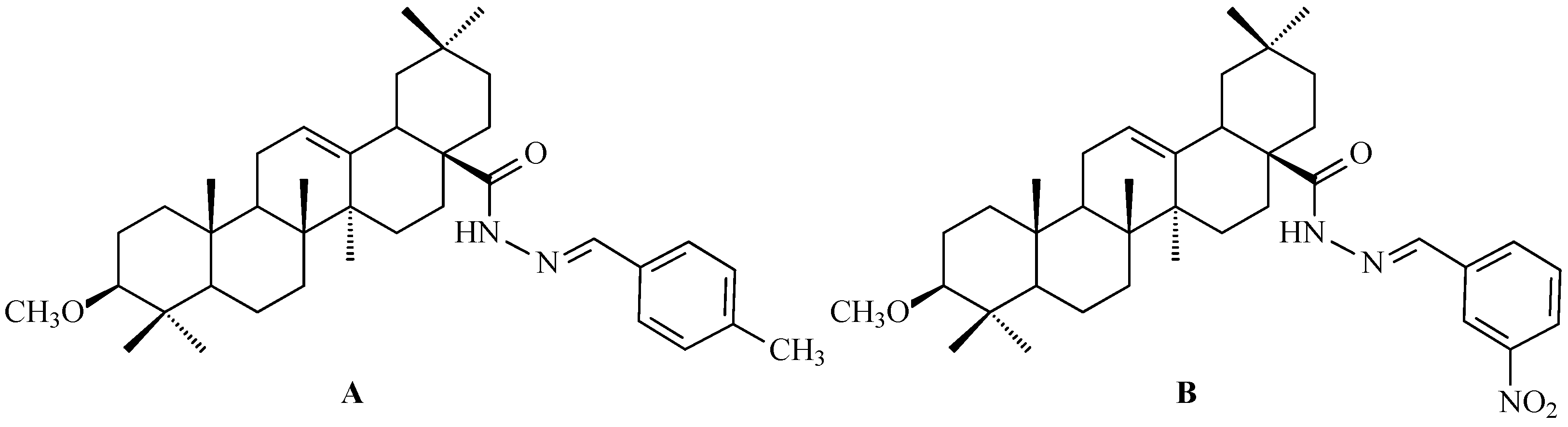

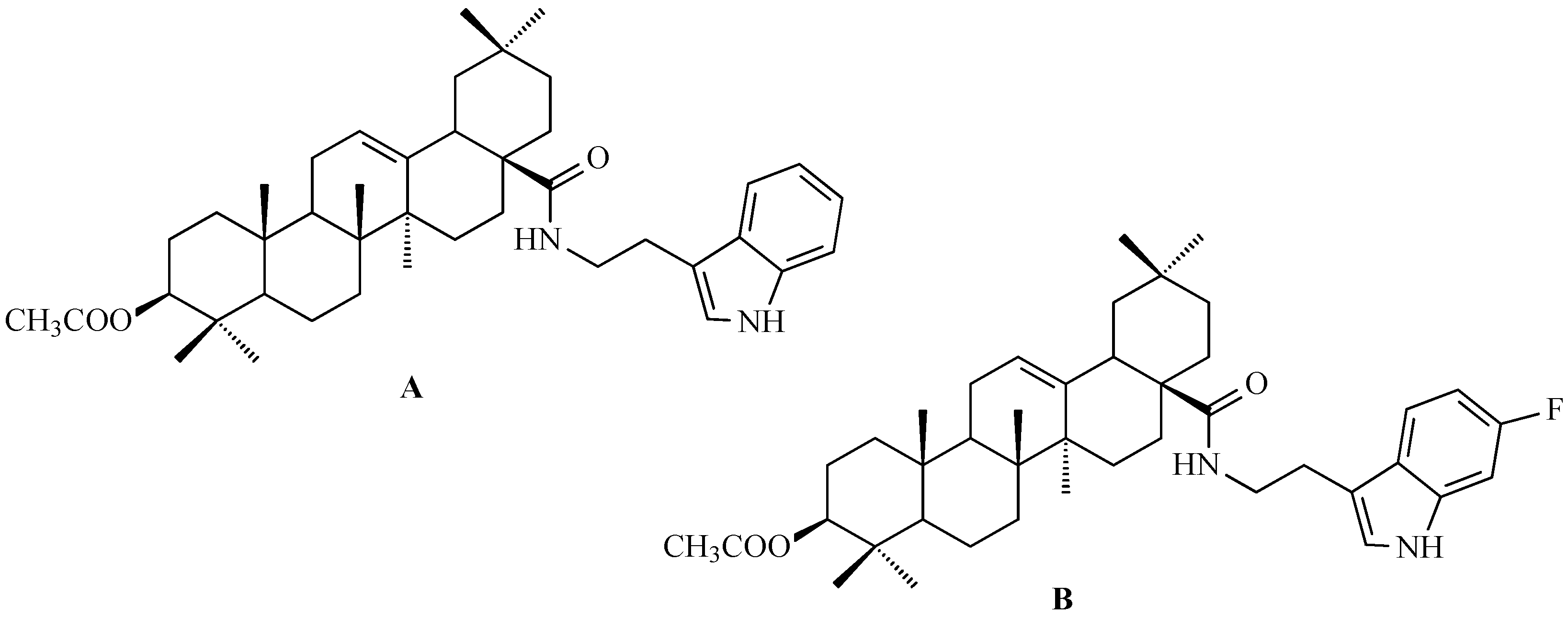

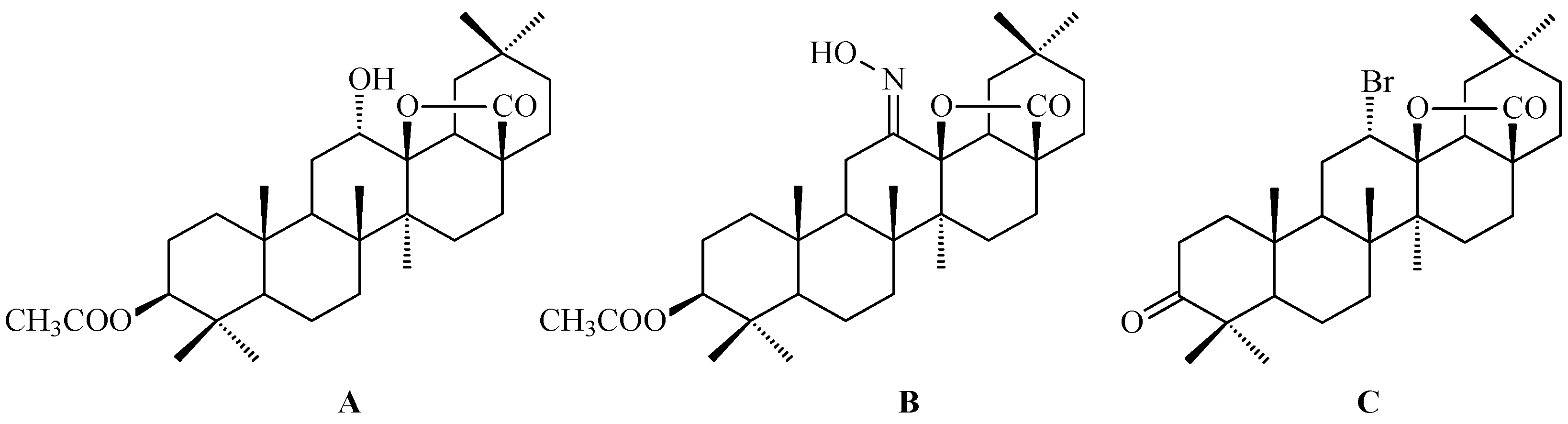

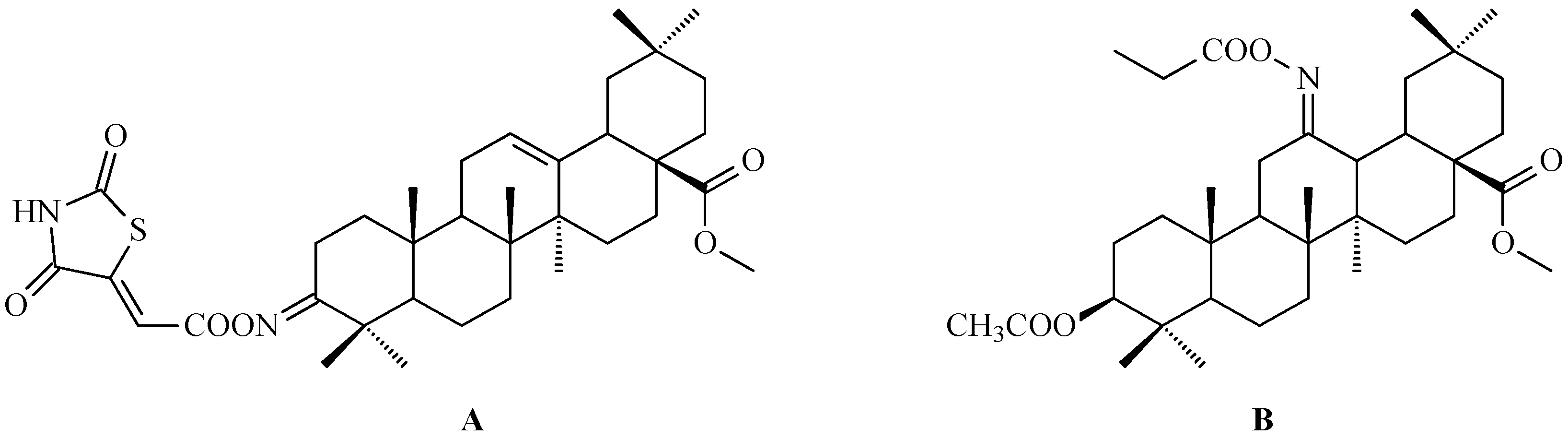

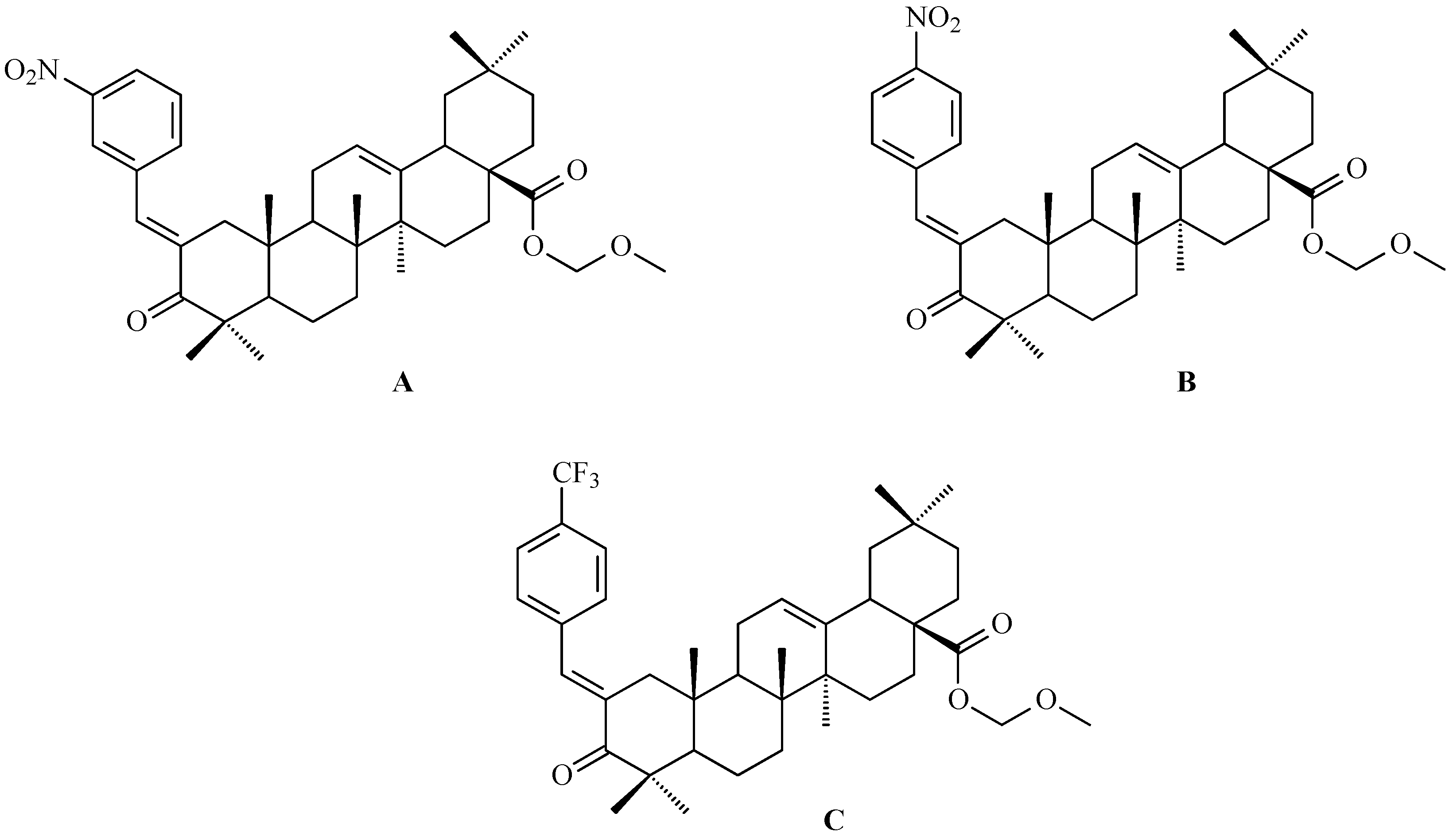

7. Enhancing Biological Activity: Structural Modifications

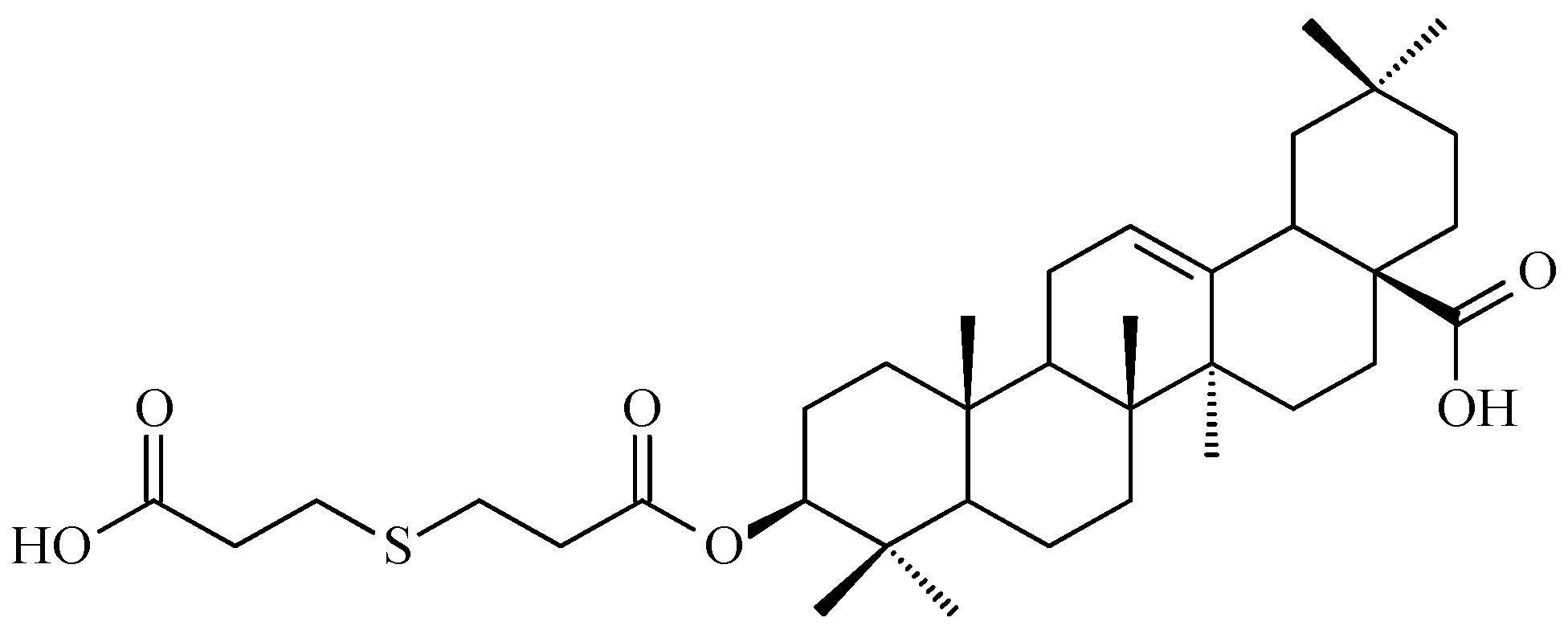

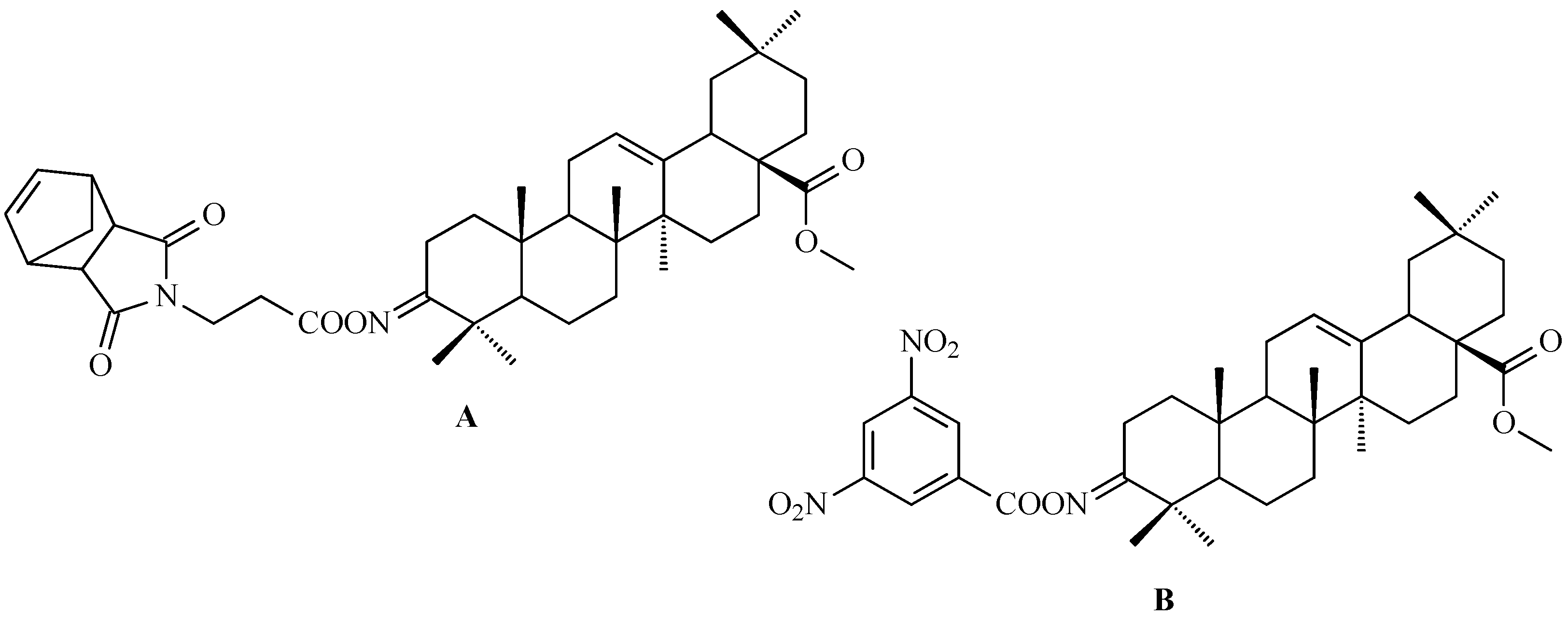

7.1. Oleanolic Acid Derivatives with a Modified the C-3 Succinyl or Propionyl Group

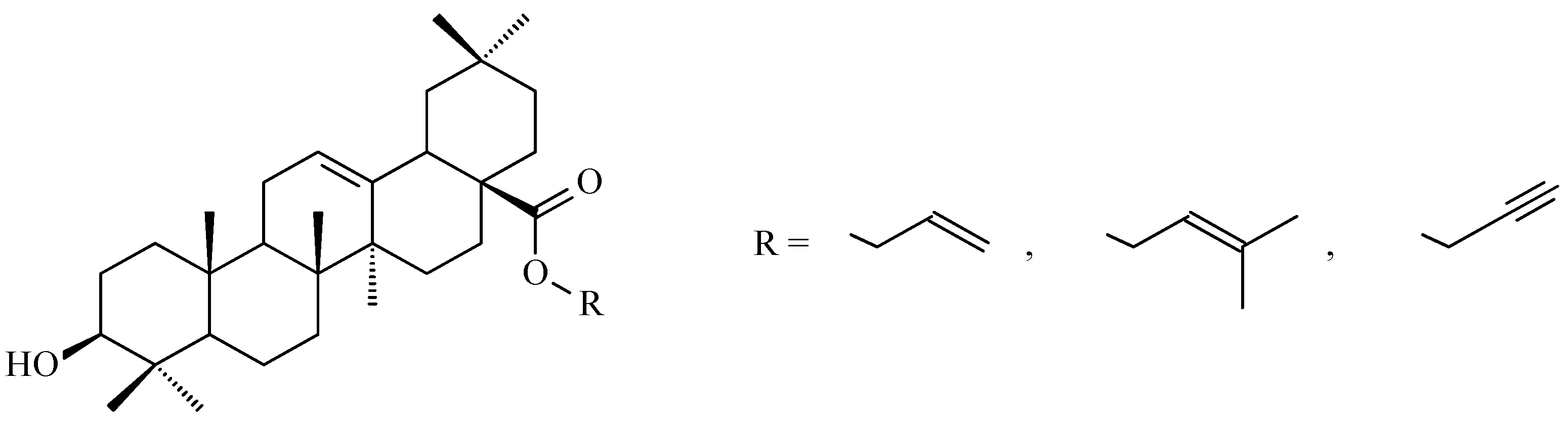

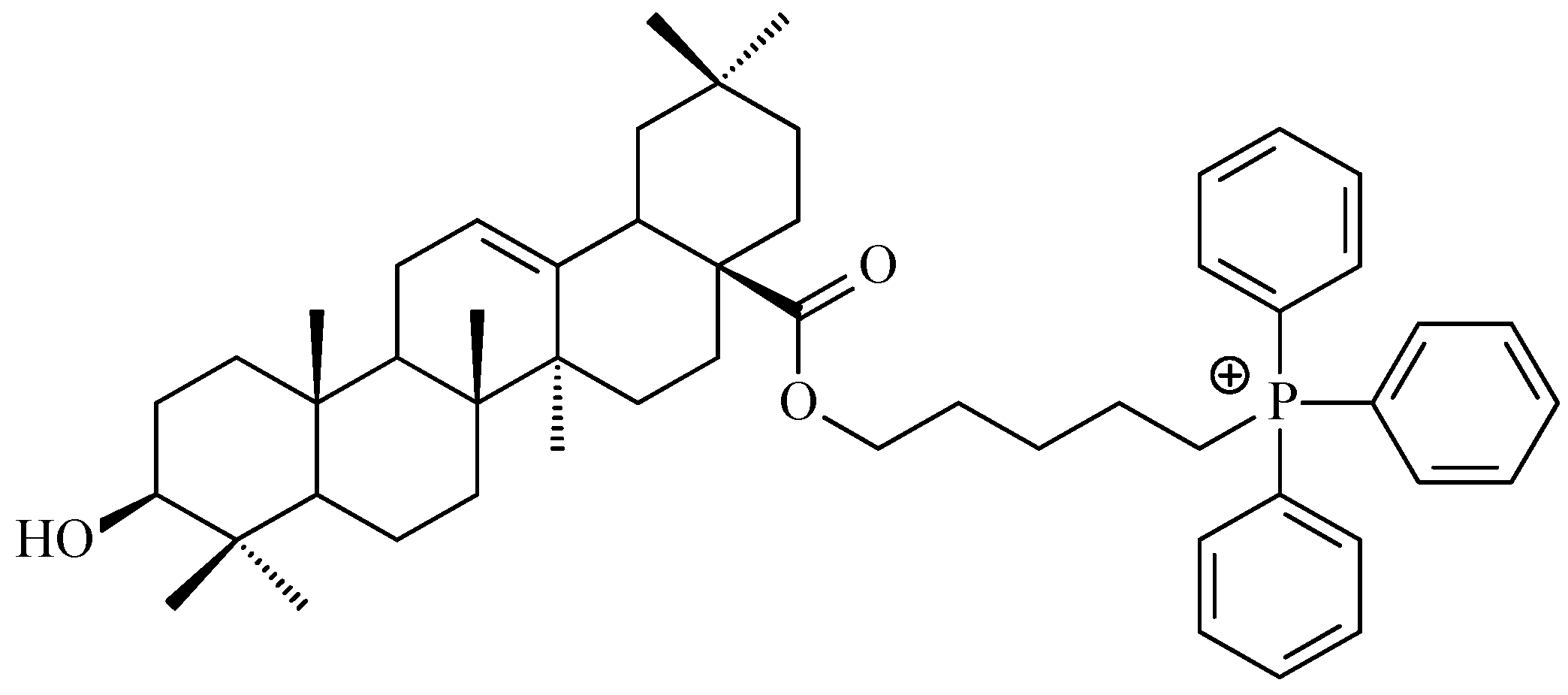

7.2. Oleanolic Acid Esters

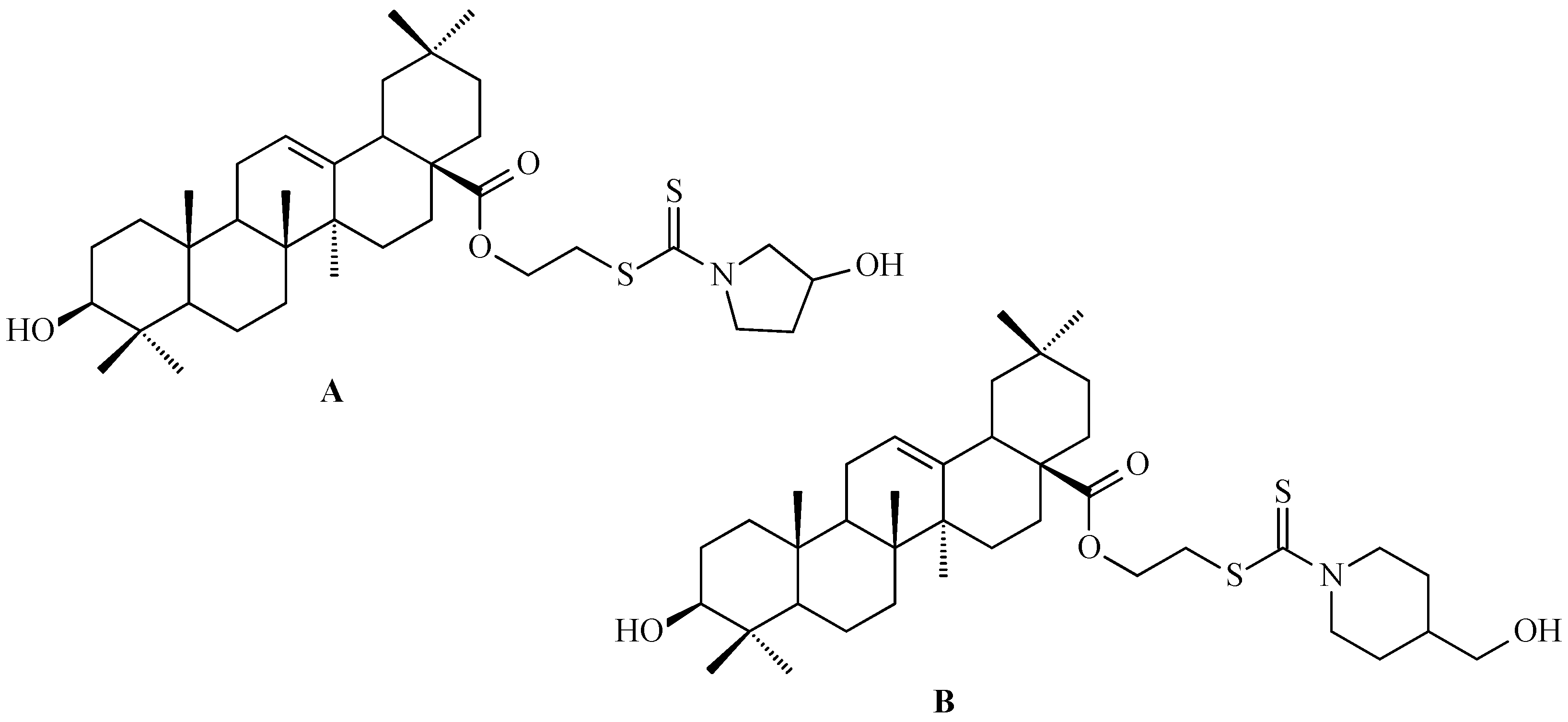

7.3. Other Derivatives of Oleanolic Acid Within the C-17 Carboxyl Group

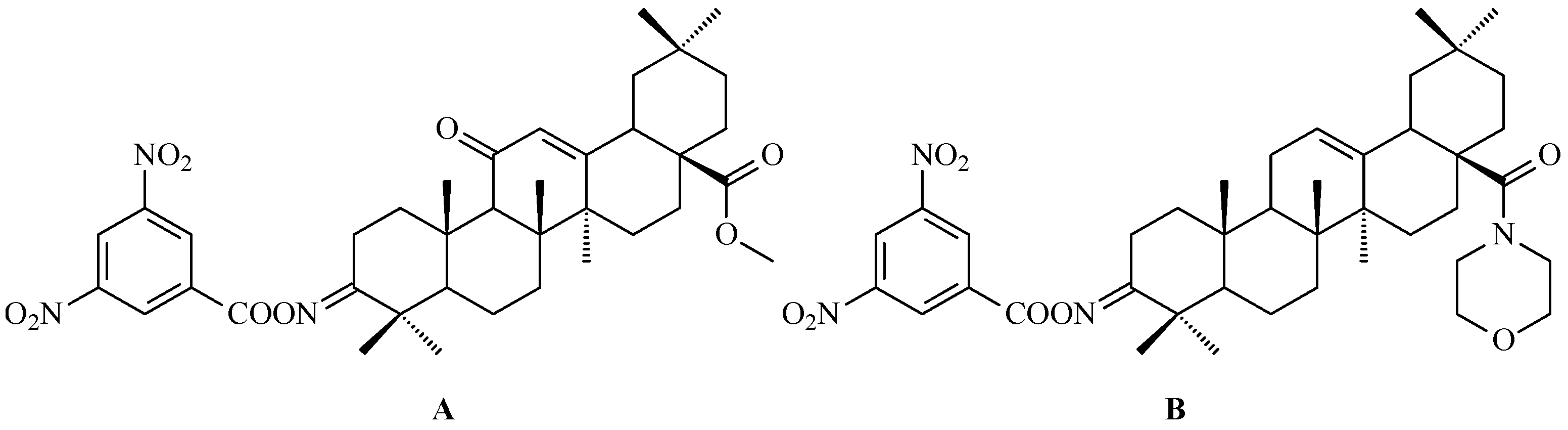

7.4. Oleanolic Acid Acylated Oximes

- (i)

- Methyl oleanonate oxime derivatives;

- (ii)

- Methyl oleanonate oxime derivatives bearing an additional 11-oxo function;

- (iii)

- Morpholide derivatives of oleanonic acid oxime.

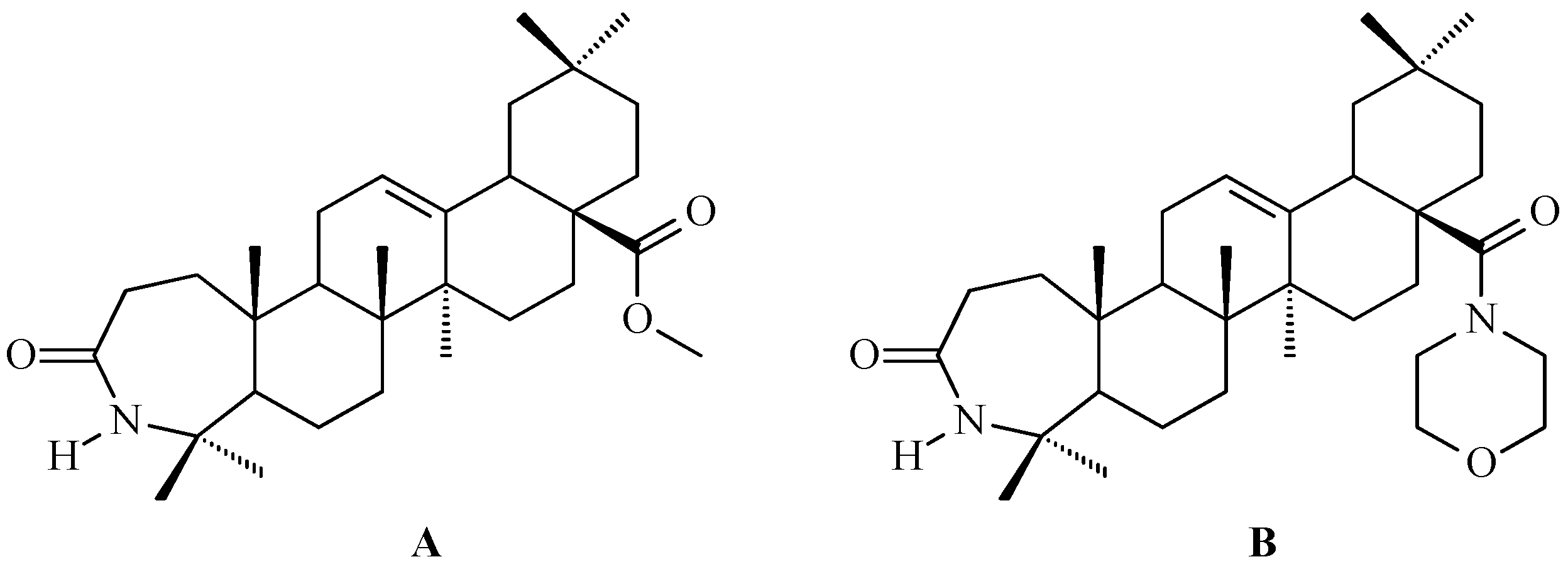

7.5. Oleanolic Acid Lactams

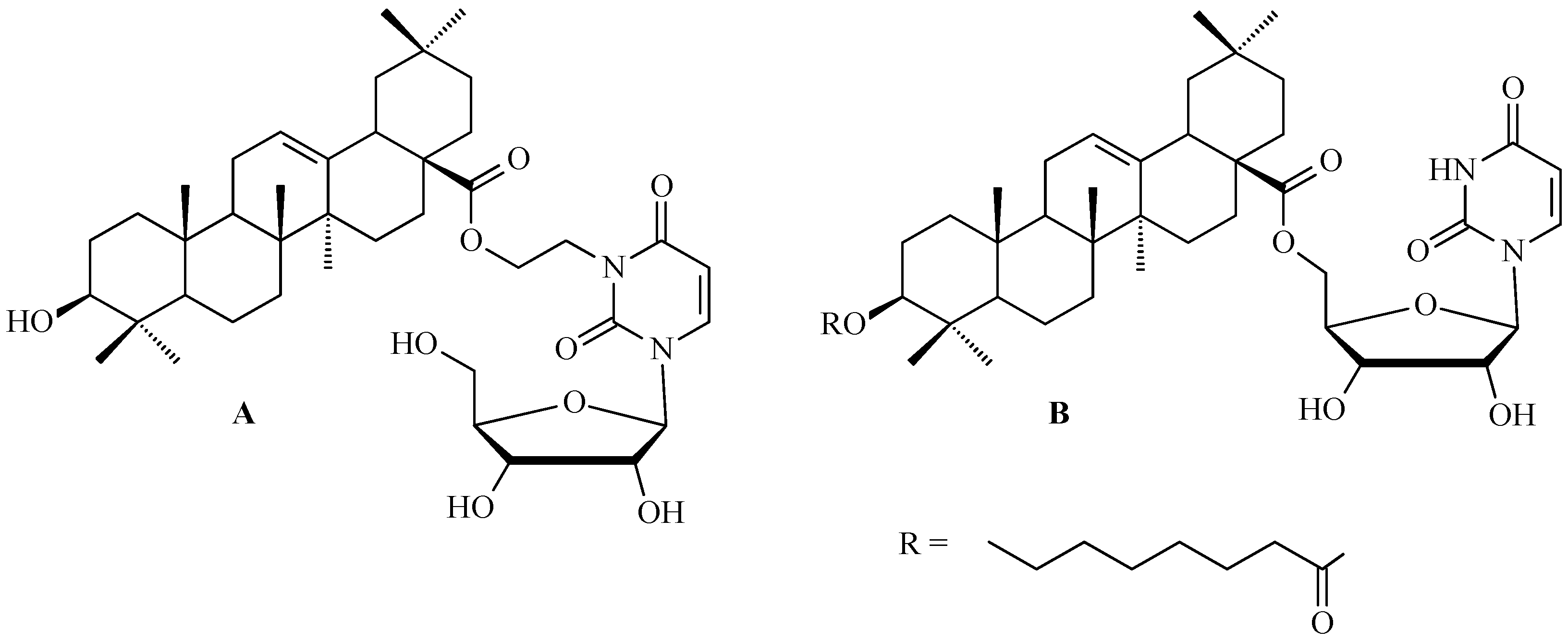

7.6. Oleanolic Acid Hybrids of Various Type

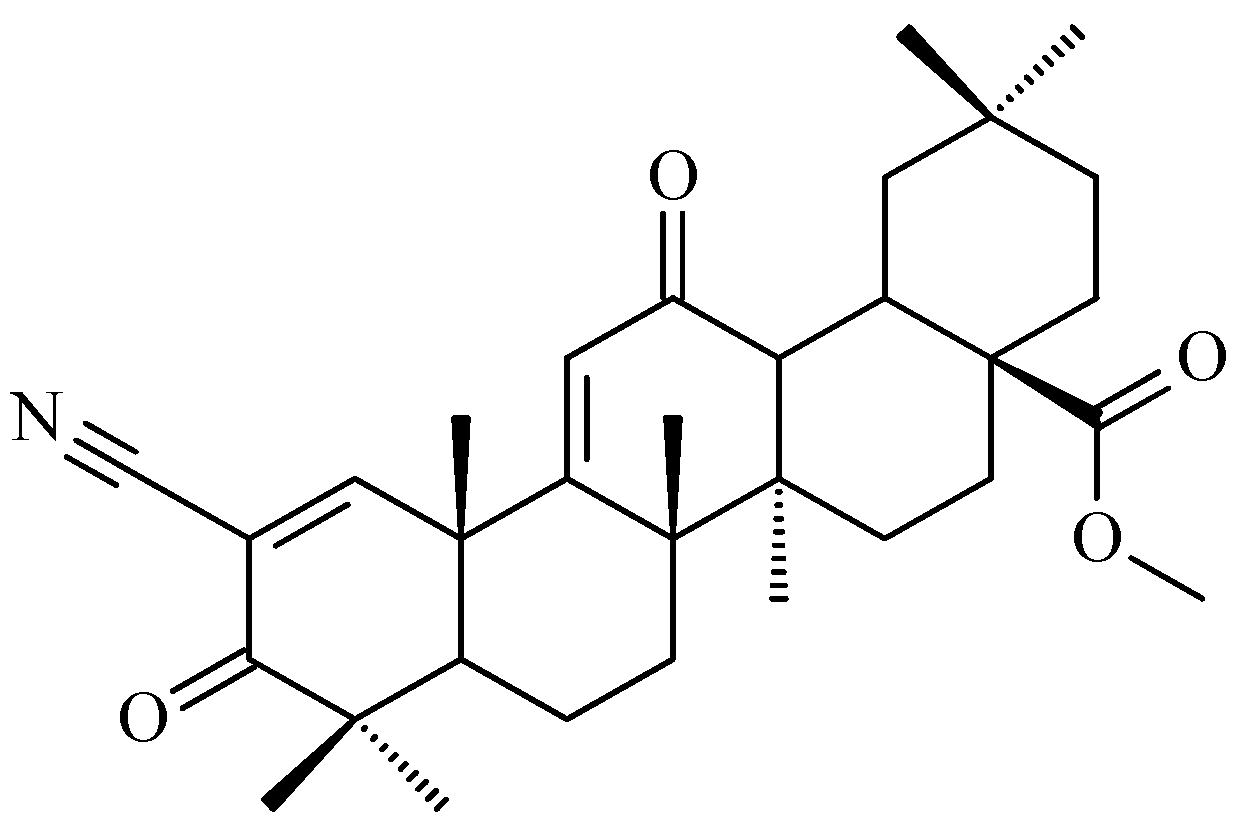

7.7. CDDO-Me

8. Enhancing Biological Activity: Nanotechnology Techniques Improving Solubility and Bioavailability

8.1. Liposomes

8.2. Proliposomes

8.3. Nanoliposomes

8.4. Nanoparticles

8.5. Nanocapsules

8.6. Solid Dispersions

8.7. Complexes with Cyclodextrins

8.8. SMEDDS

8.9. Nanoemulsions

8.10. Micelles

9. Clinical Relevance and Safety Profile of OA

9.1. Clinical Studies and Therapeutic Potential of OA

9.2. Toxicity and Safety Considerations

10. Oleanolic Acid: Cytoprotection in Normal Cells vs. Pro-Apoptotic Effects in Cancer Cells

11. Challenges and Limitations

12. Summary

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ●OH | hydroxyl radical |

| 1O2 | singlet oxygen |

| 2008 | human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| 2008.C-13 | human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| 2774 | human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| 3-MA | 3-methyladenine |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| β-TrCP | beta-transducin repeat-containing protein |

| μg/mL | microgram per milliliter = 10−6 g per 10−3 L |

| μM | micromole = 10−6 moles |

| A-549 | adenocarcinomic human alveolar basal epithelial cell line |

| ADMETox | absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity |

| AGS | gastric cancer cell line |

| AKR1B10 | aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10 |

| AKT | protein kinase B, known as PKB |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 |

| AKT/JNK | two distinct but interconnected cell signaling pathways that play roles in cell survival, apoptosis, and other cellular processes |

| AKT/mTOR/S6K | crucial molecular pathway that regulates cell growth, proliferation, protein synthesis, and metabolism |

| AKT/PKB | protein kinase B |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AP-1 | activator protein 1 |

| ASK-1 | apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 |

| ASP-831 | aspartic acid located at position 831 in the protein |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| B-16 | murine melanoma cell line |

| B-16-F-10 | murine melanoma cell line |

| BALB/c | albino, laboratory-bred strain of the house mouse |

| BAX/BCL-2 | a relationship between BCL-2-associated X protein and B-cell lymphoma 2 protein |

| BCL-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 protein |

| BCL-xL | anti-apoptotic protein that promotes cell survival by preventing programmed cell death, or apoptosis |

| BEAS-2B | human lung epithelial cell line |

| Beclin1 | protein that in humans is encoded by the BECN1 gene |

| BEL-7402 | human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line |

| BER | base excision repair system |

| bFGF | basic fibroblast growth factor |

| BGC-823 | human gastric cancer cell line |

| BIM | BCL-2–interacting mediator of cell death |

| C-3, C-12, etc. | number of C atom within the molecule of a compound (in our publication: within molecule of OA) |

| CAOV-3 | human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| CBP/p300 | CREB-binding protein (CBP) and p300 (or EP300), transcriptional coactivators |

| CDDO | 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-oic acid |

| CDDO-Me | 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-oic acid methyl ester |

| CDKs | cyclin dependent kinases |

| CDDO-Me | 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-oate |

| CEM | human T-cell leukemia cell line |

| cm/s | centimeter per second |

| cryo-SEM | cryo-scanning electron microscopy |

| CSCs | cancer stem cells |

| DISC | death-inducing signaling complex |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DR4/DR5 | death receptor 4 and death receptor 5 |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| DU-145 | human prostate cancer cell line |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMT | epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

| EPR | enhanced permeability and retention |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase, mainly ERK1 and ERK2 |

| ERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 |

| F% | bioavailability |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared |

| g/mol | grams per mole, a unit of molar mass |

| G-361 | human melanoma cell line |

| GLI-1 | glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| GMC | ganglion mother cells |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidase |

| GSK3β | glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta |

| H-22 | human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| HCT-116 | human colorectal carcinoma 116 |

| HDAC3 | histone deacetylase 3 |

| HDF | human dermal fibroblasts |

| HeLa | human epithelial adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Hep-3B | human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line |

| Hep-G2 | human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line |

| HEY | human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| HL-60 | human leukemia cell line |

| HL-7702 | normal human liver cell line |

| HNO2 | nitric acid |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 |

| HPLC | high-performance liquid chromatography |

| HPLC-MS | high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| HR | homologous recombination repair system |

| HT-29 | human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Huh-7 | human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line |

| HUVEC | human umbilical vein endothelial cell line |

| IκBα | inhibitor of kappa B alpha |

| IC50 | half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IMR-32 | human neuroblastoma cell line |

| IUPAC | The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| JAK2 | Janus kinase 2 |

| JAK2/STAT3 | crucial intracellular signaling cascade that regulates cell growth, differentiation, and immune function in response to extracellular signals like cytokines and growth factors |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| KB | human epidermal oral carcinoma cell line |

| Ki-68 | proliferation marker |

| KRAS | Kirsten rat sarcoma virus |

| L-1210 | murine lymphocytic leukemia cell line |

| L02 | normal human hepatic cell line |

| LC3-I, LC3-II | microtubule-associated protein 1 or protein 2 light chain 3 |

| LC3-II/LC3-I | ratio of two forms of the autophagy-related protein LC3, i.e., microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 |

| LCB-II | lipidated form of the protein LC3B = microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 Beta |

| LNCaP | human prostate cancer cell line |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharides |

| LY294002 | 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one |

| LYS 721 | lysine located at position 721 in the protein |

| MAFK | v-maf avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog K |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCF-10A | non-tumorigenic human mammary epithelial cell line |

| MCF-12A | normal breast epithelial cell line |

| MCF-7 | human breast cancer cell line |

| MCTs | medium-chain triglycerides |

| MDA-MB-231 | human metastatic breast cancer cell line |

| MDA-MB-435 | human metastatic breast cancer cell line |

| MDM2 | mouse double minute 2 homolog |

| mg/kg | milligrams per kilogram = 10−3 g per 103 g |

| mg/L | milligrams per liter = 10−3 g per liter |

| mg/mL | milligrams per milliliter = 10−3 g per 10−3 L |

| MKN-28 | gastric cancer cell line |

| MM-GBSA | molecular mechanics/generalized born surface area |

| MMP-7 | invasion marker |

| MMPs | matrix metalloproteinases |

| mPa x s | millipascal-second = 10−3 pascals-second |

| mPEG-P(D,L)LGA | methoxy poly(ethylene) glycol and poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) poliester |

| mPGE-PLA | methoxy poly(ethylene) glycol and poly(lactic acid) poliester |

| mPEG-PLGA | methoxy poly(ethylene) glycol and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) poliester |

| mTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin or mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| Nanog, CD-133, Oct-4, SOX2 | transcription factors which are stemness genes |

| NCI | The National Cancer Institute |

| NEm | nanoemulsion |

| NER | nucleotide excision repair system |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B cells |

| NHEJ | non-homologous end joining repair system |

| nm | nanometer = 10−9 m |

| NMP-1 | human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NO2 | nitrogen dioxide |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| •OH | hydroxyl radical |

| O2− | superoxide anion |

| OA | oleanolic acid |

| OAnano | nanoformulation of oleanolic acid |

| OA-MVLs | oleanolic acid-encapsulated multivesicular liposomes |

| OH− | hydroxide anion |

| OSCC | oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line |

| OVCAR-3 | human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| o/w | oil and water |

| P/D | phospholipid-to-drug ratio |

| P21, p27 | cell cycle regulators |

| p38 | group of mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| p53 | tumor protein p53 |

| p65 | subunit of the NF-κB transcription factor |

| Panc1 | pancreatic carcinoma-1 cell line |

| Papp | apparent permeability coefficient |

| PARP | poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| PC-3 | human prostate cancer cell line |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| pGI50 | negative logarithm of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration |

| pH | negative logarithm of the concentration of hydrogen ions (H+) in a solution |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PI3K/AKT | crucial intracellular signaling cascade that regulates cell survival, growth, and proliferation |

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | crucial intracellular signaling pathway that regulates cell growth, proliferation, survival, and metabolism |

| pLC50 | negative logarithm of the half-maximal lethal concentration |

| pTGI | negative logarithm of the total inhibition of cell growth |

| PVP | polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| RAW 264.7 | macrophage-like, Abelson leukemia virus-transformed cell line |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROR | Research Organisation Registry |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| ROS/RNS | reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species |

| SAR | structure–activity relationship |

| SD | solid dispersion |

| SHH | sonic hedgehog gene |

| SI | selectivity index |

| SiHa | human cervical squamous cell carcinoma cell line |

| SKOV-3 | human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cell line |

| SMEDDS | self-microemulsifying drug delivery system |

| SMMC-7721 | human hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Snail, Slug, Twist | transcription factors which are EMT genes |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| STAT3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| SW-480 | human colon adenocarcinoma |

| t1/2 | half-release time |

| T-24 | human bladder cancer cells |

| TGF-β1 | tumor growth factor β1 |

| TGF-β1/Smad3/Snail | molecular signaling cascade where TGF-β1 (Transforming Growth Factor-beta 1) initiates a series of events involving Smad3 and Snail to drive cellular processes like epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) |

| TGR5 | G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor |

| THP-1 | human monocytic leukemia cell line |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor α |

| TRAIL | TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand |

| U-14 | human cervical carcinoma cell line |

| U-87 | human glioblastoma cell line |

| U-937 | monocytic human cell line derived from histiocytic lymphoma |

| UA | ursolic acid |

| ULK1 | serine/threonine kinase that plays a central, initiating role in autophagy |

| UV | ultraviolet |

| var. | varietas, which means variety |

| VEGF-A | vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| Wnt, Notch, EGFR | types of cell signaling pathways that are crucial for processes like embryonic development, cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration |

References

- Kiri, S.; Ryba, T. Cancer, metastasis, and the epigenome. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Weng, J.; You, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wen, J.; Xia, Z.; Huang, S.; Luo, P.; Cheng, Q. Oxidative stress in cancer: From tumor and microenvironment remodeling to therapeutic frontiers. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Kabeer, A.; Abbas, Z.; Siddiqui, H.A.; Călina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cho, W.C. Interplay of oxidative stress, cellular communication and signaling pathways in cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.V.; Javadov, S.; Sommer, N. Cellular ROS and antioxidants: Physiological and pathological pole. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizuayehu, H.M.; Ahmed, K.Y.; Kibret, G.D.; Dadi, A.F.; Belachew, S.A.; Bagade, T.; Tegegne, T.K.; Venchiarutti, R.L.; Kibret, K.T.; Hailegebireal, A.H.; et al. Global disparities of cancer and its projected burden in 2050. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2443198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Hoskins, C. Drug development: Lessons from nature (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2017, 6, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantiniotou, M.; Athanasiadis, V.; Kalompatsios, D.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Therapeutic capabilities of triterpenes and triterpenoids in immune and inflammatory processes: A review. Compounds 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renda, G.; Gökkaya, İ.; Şöhretoğlu, D. Immunomodulatory properties of triterpenes. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 537–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, R.S.; de Jesus, B.S.M.; da Silva Luiz, S.R.; Viana, C.B.; Adão Malafaia, C.R.; Figueiredo, F.S.; Carvalho, T.D.S.C.; Silva, M.L.; Londero, V.S.; da Costa-Silva, T.A.; et al. Antiinflammatory activity of natural triterpenes—An overview from 2006 to 2021. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 1459–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darshani, P.; Sen Sarma, S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Baishya, R.; Kumar, D. Anti-viral triterpenes: A review. Phytochem. Rev. 2022, 21, 1761–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kwon, R.J.; Lee, H.S.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Jeong, H.; Park, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, T.; Yoon, S.H. The role of pentacyclic triterpenoids in non-small cell lung cancer: The mechanisms of action and therapeutic potential. Pharmaceutics 2024, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y. Comparison of the antioxidant potency of four triterpenes of Centella asiatica against oxidative stress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, A.; Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B. Oleanolic acid: A promising antioxidant–sources, mechanisms of action, therapeutic potential, and enhancement of bioactivity. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, M.F. A review on the presence of oleanolic acid in natural products. Nat. Prod. Med. 2009, 2, 77–290. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, N.; Raghuvanshi, D.S.; Singh, R.V. Recent advances in the chemistry and biology of oleanolic acid and its derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 276, 116619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Iordache, F.; Stanca, L.; Predoi, G.; Serban, A.I. Oxidative stress mitigation by antioxidants—An overview on their chemistry and influences on health status. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 209, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, S.G.; Zilhão, R.; Thorsteinsdóttir, S.; Carlos, A.R. Linking Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage to Changes in the Expression of Extracellular Matrix Components. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 673002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejchman, K.; Kotfis, K.; Sieńko, J. Biomarkers and mechanisms of oxidative stress—Last 20 years of research with an emphasis on kidney damage and renal transplantation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, V.; Hay, N. Molecular pathways: Reactive oxygen species homeostasis in cancer cells and implications for cancer therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 4309–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwar, A.; Mor, P.; Sonagara, V. Status of lipid peroxidation and antioxidation in maxillary and vocal cord carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Biochem. Res. 2021, 7, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Lin, F.; Chen, M.; Zhang, G.; Feng, Z. Research progress on the mechanism of curcumin anti-oxidative stress based on signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1548073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkowińska, A.; Formanowicz, D. Chronic kidney disease as oxidative stress- and inflammatory-mediated cardiovascular disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, B.; Zhu, H. Modulation of redox homeostasis: A strategy to overcome cancer drug resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1156538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cendrowicz, E.; Sas, Z.; Bremer, E.; Rygiel, T.P. The role of macrophages in cancer development and therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ďuračková, Z. Some current insights into oxidative stress. Physiol. Res. 2010, 59, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polimeni, M.; Gazzano, E. Is redox signaling a feasible target for overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy? Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajka-Kuźniak, V.; Baer-Dubowska, W. Modulation of Nrf2 and NF-κB signaling pathways by naturally occurring compounds in relation to cancer prevention and therapy. Are combinations better than single compounds? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.N.; Wang, X.; Zheng, X.L.; Sun, H.; Shi, X.W.; Zhong, Y.J.; Huang, B.; Yang, L.; Li, J.K.; Liao, L.C.; et al. Concurrent blockade of the NF-kappaB and Akt pathways potently sensitizes cancer cells to chemotherapeutic-induced cytotoxicity. Cancer Lett. 2010, 295, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, G.; Sun, X.; Gu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Xie, T.; et al. Natural products for enhancing the sensitivity or decreasing the adverse effects of anticancer drugs through regulating the redox balance. Chin. Med. 2024, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Rajavelu, I.; Pereira, M.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K.; Rajasekaran, J.J. Inside the genome: Understanding genetic influences on oxidative stress. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1397352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shahrani, M.; Heales, S.; Hargreaves, I.; Orford, M. Oxidative stress: Mechanistic insights into inherited mitochondrial disorders and Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Med. 2017, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waris, G.; Ahsan, H. Reactive oxygen species: Role in the development of cancer and various chronic conditions. J. Carcinog. 2006, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, D.; Lai, R.; Song, J.; Xiong, X.; Zhong, J. Emerging perspective: Role of increased ROS and redox imbalance in skin carcinogenesis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8127362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaratto, L.; Vascotto, C.; Calligaris, S.; Tell, G. The importance of redox state in liver damage. Ann. Hepatol. 2004, 3, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. MedComm 2021, 2, 618–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzawa, A.; Ichijo, H. Stress-responsive protein kinases in redox-regulated apoptosis signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005, 7, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubartelli, A.; Sitia, R. Stress as an intercellular signal: The emergence of stress-associated molecular patterns (SAMP). Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2621–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L.K. Cellular targets of oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2020, 20–21, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanza, A.; Carlesso, A.; Chintha, C.; Creedican, S.; Doultsinos, D.; Leuzzi, B.; Luís, A.; McCarthy, N.; Montibeller, L.; More, S.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling—From basic mechanisms to clinical applications. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Zheng, J.; Qi, L.; Deng, P.; Wu, M.; Li, L.; Yuan, J. Chronic stress boosts systemic inflammation and compromises antiviral innate immunity in Carassius gibel. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1105156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Silva, R.; Melo, T.M.V.D.P.e.; Inga, A.; Saraiva, L. P53 and the ultraviolet radiation-induced skin response: Finding the light in the darkness of triggered carcinogenesis. Cancers 2024, 16, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pflaum, J.; Schlosser, S.; Müller, M. p53 Family and cellular stress responses in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.G.; O’Neill, E. PI3K/Akt-mediated regulation of p53 in cancer. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2014, 42, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirone, M.; Garufi, A.; di Renzo, L.; Granato, M.; Faggioni, A.; D’Orazi, G. Zinc supplementation is required for the cytotoxic and immunogenic effects of chemotherapy in chemoresistant p53-functionally deficient cells. Oncoimmunology 2013, 2, e26198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, A.; Zalewski, P.; Sip, S.; Bednarczyk–Cwynar, B. Exploring the potential of oleanolic acid dimers–cytostatic and antioxidant activities, molecular docking, and ADMETox profile. Molecules 2024, 29, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, A.; Zalewski, P.; Sip, S.; Ruszkowski, P.; Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B. Oleanolic acid dimers with potential application in medicine—Design, synthesis, physico-chemical characteristics, cytotoxic and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, A.; Zalewski, P.; Sip, S.; Ruszkowski, P.; Bednarczyk–Cwynar, B. Acetylation of oleanolic acid dimers as a method of synthesis of powerful cytotoxic agents. Molecules 2024, 29, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollier, J.; Goossens, A. Oleanolic acid. Phytochemistry 2012, 77, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noolvi, M.; Singh, S.; Yadav, C. Quantification of oleanolic acid in the flower of Gentiana olivieri Griseb. by HPLC. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2012, 3, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Hang, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y. Determination of oleanolic acid in human plasma and study of its pharmacokinetics in chinese healthy male volunteers by HPLC tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2005, 40, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Fernández, A.; Garrido, Y.; Iniesta-López, E.; de los Ríos, A.P.; Quesada-Medina, J.; Hernández-Fernández, F.J. Recovering polyphenols in aqueous solutions from olive mill wastewater and olive leaf for biological applications. Processes 2023, 11, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinda, Á.; Castellano, J.M.; Santos-Lozano, J.M.; Delgado-Hervás, T.; Gutiérrez-Adánez, P.; Rada, M. Determination of major bioactive compounds from olive leaf. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Nowicka, P.; Turkiewicz, I.P.; Tkacz, K.; Hernández, F. Comparison of bioactive compounds and health promoting properties of fruits and leaves of apple, pear and quince. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soursouri, A.; Hosseini, S.M.; Fattahi, F. Biochemical analysis of European mistletoe (Viscum album L.) foliage and fruit settled on Persian ironwood (Parrotia persica C. A. Mey.) and hornbeam (Carpinus betulus L.). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 22, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunoki, K.; Sasaki, G.; Tokuji, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Naito, A.; Aida, K.; Ohnishi, M. Effect of dietary wine pomace extract and oleanolic acid on plasma lipids in rats fed high-fat diet and its DNA microarray analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 12052–12058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biltekin, S.İ.; Göğüş, F.; Yanık, D.K. Valorization of olive pomace: Extraction of maslinic and oleanolic by using closed vessel microwave extraction system. Waste Biomass Valor. 2022, 13, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elouafy, Y.; Mortada, S.; Yadini, A.E.; Hnini, M.; Aalilou, Y.; Harhar, H.; Khalid, A.; Abdalla, A.N.; Bouyahya, A.; Faouzi, M.E.A.; et al. Bioactivity of walnut: Investigating the triterpenoid saponin extracts of Juglans regia kernels for antioxidant, anti-diabetic, and antimicrobial properties. Prog. Microbes Mol. Biol. 2023, 6, a0000325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannus, F.; Sainz, J.; Reyes-Zurita, F.J. Principal bioactive properties of oleanolic acid, its derivatives, and analogues. Molecules 2024, 29, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treml, J.; Večeřová, P.; Herczogová, P.; Šmejkal, K. Direct and indirect antioxidant effects of selected plant phenolics in cell-based assays. Molecules 2021, 26, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odun-Ayo, F.; Chetty, K.; Reddy, L. Determination of the ursolic and oleanolic acids content with the antioxidant capacity in apple peel extract of various cultivars. Braz. J. Biol. 2022, 82, 258442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ye, X.; Liu, R.; Chen, H.; Bai, H.; Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Hai, C. Antioxidant activities of oleanolic acid in vitro: Possible role of Nrf2 and MAP kinases. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 184, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesslbauer, B.; Bochkov, V. Biochemical targets of drugs mitigating oxidative stress via redox-independent mechanisms. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 1225–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S. Oleanolic acid improved inflammatory response and apoptosis of PC12 cells induced by OGD/R through downregulating miR-142-5p. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwiecki, K.; Przybył, K.; Dezor, D.; Bąkowska, E.; Rocha, S.M. Interactions of oleanolic acid, apigenin, rutin, resveratrol and ferulic acid with phosphatidylcholine lipid membranes–a spectroscopic and machine learning study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, P.K.; Kandhavelu, M.; Reetha, D. Antioxidant properties of the oleanolic acid isolated from Cassia auriculata (Linn). J. Pharm. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 4, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivam, N.; Kim, Y.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Kim, D. Oxidative stress, genomic integrity, and liver diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matysik-Woźniak, A.; Oaduch, R.; Maciejewski, R.; Jünemann, A.G.; Rejdak, R. The impact of oleanolic and ursolic acid on corneal epithelial cells in vitro. Ophthalmol. J. 2016, 1, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konaté, M.M.; Antony, S.; Doroshow, J.H. Inhibiting the activity of NADPH oxidase in cancer. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 33, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Khalaji, A.; Najafi, M.B.; Sadati, S.; Raisi, A.; Abolhassani, A.; Eshraghi, R.; Mahabady, M.K.; Rahimian, N.; Mirzaei, H. NF-κB pathway and angiogenesis: Insights into colorectal cancer development and therapeutic targets. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, S.; Ma, J.; Liu, F.; Fang, Y.; Cao, F.; Wang, L.; Pei, Z.; Ren, J. Pentacyclic triterpene oleanolic acid protects against cardiac aging through regulation of mitophagy and mitochondrial integrity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2022, 1868, 166402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Morishita, K.; Nagasawa, T. Oleanolic acid induces lipolysis and antioxidative activity in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2021, 27, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaunig, J.E.; Wang, Z.; Pu, X.; Zhou, S. Oxidative stress and oxidative damage in chemical carcinogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 254, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczek, C.R.; Chandel, N.S. The two faces of reactive oxygen species in cancer. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2016, 1, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadet, J.; Wagner, J.R. DNA base damage by reactive oxygen species, oxidizing agents, and UV radiation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.S.; Evans, M.D.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lunec, J. Oxidative DNA damage: Mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Chen, H.; Liang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Luo, C.; Tang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Q.; et al. Dual role of reactive oxygen species and their application in cancer therapy. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 5543–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyenberg, M.; Ferreira da Silva, J.; Loizou, J.I. Tissue specific DNA repair outcomes shape the landscape of genome editing. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 728520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, J.P.; van Steeg, H.; Luijten, M. Oxidative DNA damage and nucleotide excision repair. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, T.; Petry, A.; Shvetsova, A.; Gerhold, J.M.; Görlach, A. The epigenetic landscape related to reactive oxygen species formation in the cardiovascular system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1533–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, Y.Q. Role of reactive oxygen species in regulating epigenetic modifications. Cell Signal. 2025, 125, 111502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.P.; Harris, C.C. Inflammation and cancer: An ancient link with novel potentials. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, J.; Song, J.; Kim, R.; Hwang, A. Oleanolic acid regulates NF-κB signaling by suppressing MafK expression in RAW 264.7 cells. BMB Rep. 2014, 47, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.B.; Wang, R.X.; Deng, H.J.; Wang, Y.H.; Tang, J.D.; Cao, F.Y.; Wang, J.H. Protective effects of oleanolic acid on oxidative stress and the expression of cytokines and collagen by the AKT/NF-κB pathway in silicotic rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 3121–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.W.; Guo, H.Q.; Zhou, G.B.; Li, J.Y.; Su, B. Oleanolic acid suppresses the proliferation of human bladder cancer by Akt/mTOR/S6K and ERK1/2 signaling. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 13864–13870. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Lin, J.; Sun, G.; Wei, L.; Shen, A.; Zhang, M.; Peng, J. Oleanolic acid inhibits colorectal cancer angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro via suppression of STAT3 and Hedgehog pathways. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 5276–5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, M.; Greenbaum, J.; Deeds, E. Crosstalk and the evolvability of intracellular communication. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 16009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sam, S.A.; Teel, J.; Tegge, A.N.; Bharadwaj, A.; Murali, T.M. XTalkDB: A database of signaling pathway crosstalk. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D432–D439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phull, A.R.; Arain, S.Q.; Majid, A.F.; Humaira, A.M.; Kim, S.J. Oxidative stress-mediated epigenetic remodeling, metastatic progression and cell signaling in cancer. Oncologie 2024, 26, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Guo, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, S.; Gong, H.; Zhang, B.K.; Yan, M. Dissecting the crosstalk between Nrf2 and NF-κB response pathways in drug-induced toxicity. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 809952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gado, F.; Ferrario, G.; Della Vedova, L.; Zoanni, B.; Altomare, A.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G.; Baron, G. Targeting Nrf2 and NF-κB signaling pathways in cancer prevention: The role of apple phytochemicals. Molecules 2022, 28, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žiberna, L.; Šamec, D.; Mocan, A.; Nabavi, S.F.; Bishayee, A.; Farooqi, A.A.; Sureda, A.; Nabavi, S.M. Oleanolic acid alters multiple cell signaling pathways: Implication in cancer prevention and therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratheeshkumar, P.; Kuttan, G. Oleanolic acid induces apoptosis by modulating p53, BAX, BCL-2 and caspase-3 gene expression and regulates the activation of transcription factors and cytokine profile in B16F. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2011, 30, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Ma, X.; Tang, Z. Anticancer activity of oleanolic acid and its derivatives: Recent advances in evidence, target profiling and mechanisms of action. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 145, 112397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Chen, D.; Ni, J.; Kang, Y.; Wang, S. Oleanolic acid induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells through caspase activation and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2007, 39, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Cao, Y.; Li, P.; Tang, X.; Yang, M.; Gu, S.; Xiong, K.; Li, T.; Xiao, T. Oleanolic acid induces autophagy and apoptosis via the AMPK-mTOR signaling pathway in colon cancer. J. Oncol. 2020, 2021, 8281718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wang, P.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, J.; Du, H.; Wang, Z.; Duan, Z.; Lei, H.; Li, H. Induction of apoptosis by an oleanolic acid derivative in SMMC-7721 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 2821–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.J.; Jo, H.J.; Lee, K.J.; Choi, J.W.; An, J.H. Oleanolic acid induces p53-dependent apoptosis via the ERK/JNK/AKT pathway in cancer cell lines in prostatic cancer xenografts in mice. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 26370–26386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoo, E.; Han, S.; Jung, G.; Han, E.; Jung, S.; Seok Kim, B.; Cho, S.; Nam, J.; Choi, C.; et al. Oleanolic acid induces apoptosis and autophagy via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in AGS human gastric cancer cells. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 87, 104854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Chen, W.; Yin, L.; Zhu, J.; Chen, N.; Chen, W. Oleanolic acid induces apoptosis of MKN28 cells via AKT and JNK signaling pathways. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Song, Q.; Hu, D.; Zhuang, X.; Yu, S.; Teng, D. Oleanolic acid induced autophagic cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via PI3K/Akt/mTOR and ROS-dependent pathway. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2016, 20, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lúcio, K.A.; Rocha, G.G.; Monção-Ribeiro, L.C.; Fernandes, J.; Takiya, C.M.; Gattass, C.R. Oleanolic acid initiates apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines and reduces metastasis of a B16F10 melanoma model in vivo. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Li, X.; Yu, S.; Liang, L. Inhibition of cancer cell growth by oleanolic acid in multidrug resistant liver carcinoma is mediated via suppression of cancer cell migration and invasion, mitochondrial apoptosis, G2/M cell cycle arrest and deactivation of JNK/p38 signalling pathway. J. BUON 2019, 24, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, L.; Ma, L.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, N.; Liu, G.; Lin, X. Oleanolic acid inhibits proliferation and invasiveness of Kras-transformed cells via autophagy. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, T.; Tian, Y.; Li, H. Nanocrystallized oleanolic acid better inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion in intracranial glioma via caspase-3 pathway. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebe, N.; Miele, L.; Harris, P.J.; Jeong, W.; Bando, H.; Kahn, M.; Yang, S.X.; Ivy, S.P. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: Clinical update. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, L.T.H.; Sari, I.N.; Yang, Y.G.; Lee, S.H.; Jun, N.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kwon, H.Y. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) in drug resistance and their therapeutic implications in cancer treatment. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 2018, 5416923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batlle, E.; Clevers, H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazio, F.; Bordi, M.; Cianfanelli, V.; Locatelli, F.; Cecconi, F. Autophagy and cancer stem cells: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.H.; Chou, H.E.; Hou, H.H.; Kuo, W.T.; Liu, W.W.; Yen-Ping Kuo, M.; Cheng, S.J. Oleanolic acid inhibits aldo-keto reductase family 1 member B10-induced cancer stemness and avoids cisplatin-based chemotherapy resistance via the Snail signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. J. Dent. Sci. 2025, 20, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wu, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhou, J.; Zhuang, H.; Li, W. Oleanolic acid inhibits colon cancer cell stemness and reverses chemoresistance by suppressing JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Biocell 2024, 48, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.B.; Gao, J.; Li, X.; Thangaraju, M.; Panda, S.S.; Lokeshwar, B.L. Cytotoxic autophagy: A novel treatment paradigm against breast cancer using oleanolic acid and ursolic acid. Cancers 2024, 16, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Yang, X.; Du, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T. Dual strategies to improve oral bioavailability of oleanolic acid: Enhancing water-solubility, permeability and inhibiting cytochrome P450 isozymes. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 99, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triaa, N.; Znati, M.; Jannet, H.B.; Bouajila, J. Biological activities of novel oleanolic acid derivatives from bioconversion and semi-synthesis. Molecules 2024, 29, 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasim, M.; Bergonzi, M.C. Unlocking the potential of oleanolic acid: Integrating pharmacological insights and advancements in delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Liu, J.; Wen, X.; Sun, H. Synthesis and cytotoxicity evaluation of oleanolic acid derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 2074–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Zurita, F.J.; Medina-O’Donnell, M.; Ferrer-Martín, R.M.; Rufino-Palomares, E.E.; Martin-Fonseca, S.; Rivas, F.; Martinez, A.; Garcia-Granados, A.; Pérez-Jiménez, A.; García-Salguero, L.; et al. The oleanolic acid derivative, 3-O-succinyl-28-O-benzyl oleanolate, induces apoptosis in B16-F10 melanoma cells via the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 93590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Luan, T.; Liu, F. Design and synthesis of novel oleanolic acid-linked disulfide, thioether, or selenium ether moieties as potent cytotoxic agents. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallavadhani, U.V.; Mahapatra, A.; Pattnaik, B.; Vanga, N.; Suri, N.; Saxena, A.K. Synthesis and anti-cancer activity of some novel C-17 analogs of ursolic and oleanolic acids. Med. Chem. Res. 2013, 22, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, B.; Chen, R.; Wang, N.; Lu, Y.; Shi, F.; Dehaen, W.; Huai, Q. Synthesis and discovery of mitochondria-targeting oleanolic acid derivatives for potential PI3K inhibition. Fitoterapia 2022, 162, 105291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, Q.; Du, F.; Wu, X.; Li, M.; Shen, J.; Deng, S.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Synthesis of oleanolic acid-dithiocarbamate conjugates and evaluation of their broad-spectrum antitumor activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halil, Ş.; Berre, M.; Rabia Büşra, Ş.; Halil Burak, K.; Ebru, H. Synthesis of oleanolic acid hydrazide-hydrazone hybrid derivatives and investigation of their cytotoxic effects on A549 human lung cancer cells. Results Chem. 2021, 4, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bildziukevich, U.; Kvasnicová, M.; Šaman, D.; Rárová, L.; Wimmer, Z. Novel oleanolic acid-tryptamine and -Fluorotryptamine amides: From adaptogens to agents targeting in vitro cell apoptosis. Plants 2021, 10, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Günther, A.; Ruszkowski, P.; Sip, S.; Zalewski, P. Oleanolic acid lactones as effective agents in the combat with cancers—Cytotoxic and antioxidant activity, SAR analysis, molecular docking and ADMETox profile. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminskyy, D.; Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Vasylenko, O.; Kazakova, O.; Zimenkovsky, B.; Zaprutko, L.; Lesyk, R. Synthesis of new potential anticancer agents based on 4-thiazolidinone and oleanane scaffolds. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 3568–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Zaprutko, L.; Ruszkowski, P.; Hładoń, B. Anti-cancer effect of A-ring or/and C-ring modified oleanolic acid derivatives on KB, MCF-7 and HeLa cell lines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 2201–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Ruszkowski, P.; Atamanyuk, D.; Lesyk, R.; Zaprutko, L. Hybrids of oleanolic acid with norbornene-2,3-dicarboximide-N-carboxylic acids as potential anticancer agents. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2017, 74, 827–835. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Ruszkowski, P.; Jarosz, T.; Krukiewicz, K. Enhancing anticancer activity through the combination of bioreducing agents and triterpenes. Future Med. Chem. 2018, 10, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Ruszkowski, P. Acylation of oleanolic acid oximes effectively improves cytotoxic activity in in vitro studies. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Ruszkowski, P.; Bobkiewicz-Kozlowska, T.; Zaprutko, L. Oleanolic acid A-lactams inhibit the growth of HeLa, KB, MCF-7 and Hep-G2 cancer cell lines at micromolar concentrations. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Su, H.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zheng, T.; Chen, F. Conjugation of uridine with oleanolic acid derivatives as potential antitumor agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2016, 88, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, H.; Ghaffari-Moghaddam, M.; Bulut, Ş.; Akbaş, F.; Köse, A.; Topçu, G. Synthesis and anticancer activity of novel derivatives of α,β-unsaturated ketones based on oleanolic acid: In vitro and in silico studies against prostate cancer cells. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202301089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, T.; Rounds, B.V.; Bore, L.; Favaloro, F.G.; Gribble, G.W.; Suh, N.; Wang, Y.; Sporn, M.B. Novel synthetic oleanane triterpenoids: A series of highly active inhibitors of nitric oxide production in mouse macrophages. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999, 9, 3429–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, N.; Wang, Y.; Honda, T.; Gribble, G.W.; Dmitrovsky, E.; Hickey, W.F.; Maue, R.A.; Place, A.E.; Porter, D.M.; Spinella, M.J.; et al. A novel synthetic oleanane triterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid, with potent differentiating, antiproliferative, and anti-inflammatory activity. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.; Raina, D.; Meyer, C.; Kufe, D. Triterpenoid CDDO-methyl ester inhibits the Janus-activated kinase-1 (JAK1)→signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (STAT3) pathway by direct inhibition of JAK1 and STAT3. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 2920–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Place, A.E.; Suh, N.; Williams, C.R.; Risingsong, R.; Honda, T.; Honda, Y.; Gribble, G.W.; Leesnitzer, L.M.; Stimmel, J.B.; Willson, T.M.; et al. The novel synthetic triterpenoid, CDDO-imidazolide, inhibits inflammatory response and tumor growth in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 2798–2806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lapillonne, H.; Konopleva, M.; Tsao, T.; Gold, D.; McQueen, T.; Sutherland, R.L.; Madden, T.; Andreeff, M. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma by a novel synthetic triterpenoid 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid induces growth arrest and apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 5926–5939. [Google Scholar]

- Melichar, B.; Konopleva, M.; Hu, W.; Melicharova, K.; Andreeff, M.; Freedman, R.S. Growth-inhibitory effect of a novel synthetic triterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxoolean-1,9-dien-28-oic acid, on ovarian carcinoma cell lines not dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma expression. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004, 93, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihunnah, C.A.; Ghosh, S.; Hahn, S.; Straub, A.C.; Ofori-Acquah, S.F. Nrf2 Activation with CDDO-methyl promotes beneficial and deleterious clinical effects in transgenic mice with sickle cell anemia. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 880834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, P.E.; Raskin, P.; Toto, R.D.; Meyer, C.J.; Huff, J.W.; Grossman, E.B.; Krauth, M.; Ruiz, S.; Audhya, P.; Christ-Schmidt, H.; et al. BEAM Study Investigators. Bardoxolone methyl and kidney function in CKD with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staicu, V.; Tomescu, J.A.; Calinescu, I. Bioavailability of ursolic/oleanolic acid, with therapeutic potential in chronic diseases and cancer. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2024, 33, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J. A review of liposomes as a drug delivery system: Current status of approved products, regulatory environments, and future perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Huang, J.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Xiong, D.; Sun, X.; Zhong, Z. Effect of a controlled-release drug delivery system made of oleanolic acid formulated into multivesicular liposomes on hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Song, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ping, Q. Preparation of silymarin proliposome: A new way to increase oral bioavailability of silymarin in beagle dogs. Int. J. Pharm. 2006, 319, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gao, X. Study on preparation of a new oleanolic acid proliposomes and its properties. Chin. Pharm. J. 2007, 42, 839–843. [Google Scholar]

- Mozafari, M.R.; Khosravi-Darani, K.; Borazan, G.G.; Cui, J.; Pardakhty, A.; Yurdugul, S. Encapsulation of food ingredients using nanoliposome technology. Int. J. Food Prop. 2008, 11, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Gao, D.; Zhao, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, X. An evaluation of the anti-tumor efficacy of oleanolic acid-loaded PEGylated liposomes. Nanotechnology 2013, 24, 235102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Yuhong, J.; Xin, P.; Han, J.L.; Du, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; et al. Advances in nanotechnology for enhancing the solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 1469–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, D.K.W.; Casettari, L.; Cespi, M.; Bonacucina, G.; Palmieri, G.F.; Sze, S.C.W.; Leung, G.P.H.; Lam, J.K.W.; Kwok, P.C.L. Oleanolic acid loaded PEGylated PLA and PLGA nanoparticles with enhanced cytotoxic activity against cancer cells. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 2112–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Gigliobianco, M.R.; Censi, R.; Di Martino, P. Polymeric nanocapsules as nanotechnological alternative for drug delivery system: Current status, challenges and opportunities. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.Z.; Liu, S.; Lei, P.; Xiao, J. Study on the release of oleanolic acid loaded nanocapsules in vitro. Zhong Yao Cai 2008, 31, 283–285. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wang, X. Improved dissolution of oleanolic acid with ternary solid dispersions. AAPS PharmSciTech 2007, 8, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, A.H.; Gibaldi, M.; Kanig, J.L. Increasing dissolution rates and gastrointestinal absorption of drugs via solid solutions and eutectic mixtures III. Experimental evaluation of griseofulvin-succinic acid solution. J. Pharm. Sci. 1966, 55, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaescu, O.E.; Belu, I.; Mocanu, A.G.; Manda, V.C.; Rău, G.; Pîrvu, A.S.; Ionescu, C.; Ciulu-Costinescu, F.; Popescu, M.; Ciocîlteu, M.V. Cyclodextrins: Enhancing drug delivery, solubility and bioavailability for modern therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelling-Férez, J.; López-Miranda, S.; Gabaldón, J.A.; Nicolás, F.J. Oleanolic acid complexation with cyclodextrins Iimproves its cell bio-availability and biological activities for cell migration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokania, S.; Joshi, A.K. Self-microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS)—Challenges and road ahead. Drug Deliv. 2015, 22, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Huang, X.; Dou, J.; Zhai, G.; Su, L. Self-microemulsifying drug delivery system for improved oral bioavailability of oleanolic acid: Design and evaluation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 2917–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, H.L.; Abrego, G.; Souto, E.B.; Garduño-Ramirez, M.L.; Clares, B.; García, M.L.; Calpena, A.C. Nanoemulsions for dermal controlled release of oleanolic and ursolic acids: In vitro, ex vivo and in vivo characterization. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 130, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, H.L.; Calpena, A.C.; Garduño-Ramírez, M.L.; Ortiz, R.; Melguizo, C.; Prados, J.C.; Clares, B. Nanoemulsion strategy for ursolic and oleanic acids isolates from Plumeria obtusa improves antioxidant and cytotoxic activity in melanoma cells. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotta, S.; Aldawsari, H.M.; Badr-Eldin, S.M.; Nair, A.B.; Yt, K. Progress in polymeric micelles for drug delivery applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.Y.; Yang, H.S.; Park, N.R.; Shin, B.; Lee, E.H.; Cho, S.H. Development of polymeric micelles of oleanolic acid and evaluation of their clinical efficacy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.Q.; Shen, J.; Chen, C.P.; Ma, X.; Lin, C.; Ouyang, Q.; Xuan, C.X.; Liu, J.; Sun, H.B.; Liu, J. Lipid-lowering effects of oleanolic acid in hyperlipidemic patients. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2018, 16, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese University of Hong Kong. A Pilot Study of Curcumin and Ginkgo for Treating Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01674946 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Castellano, J.M. Bioavailability of Oleanolic Acid Formulated as Functional Olive Oil (BIO-OLTRAD). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05529953 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Castellano, J.M. Oleanolic Acid as Therapeutic Adjuvant for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (OLTRAD STUDY) (OLTRAD). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06030544 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Jimenez, E.G. Prevention with Oleanolic Acid of Insulin Resistance (PREOLIA). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05049304 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Industrial Farmacéutica Cantabria, S.A. Six-Month Single-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of a Dietary Supplement Supplement on Hair Growth in 45 Volunteers. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06841458 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Liu, J.; Lu, Y.F.; Wu, Q.; Xu, S.F.; Shi, F.G.; Klaassen, C.D. Oleanolic acid reprograms the liver to protect against hepatotoxicants, but is hepatotoxic at high doses. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Wu, Y.Q.; Xu, Y.S.; Wang, K.X.; Qin, X.M.; Lu, Y.F. LC-MS-Based metabolomic study of oleanolic acid-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, J. Hepatotoxicity from long-term administration of hepatoprotective low doses of oleanolic acid in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 497, 117277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.; Du, X.; Chen, S.; Feng, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; He, X.; Wang, R.; et al. Oral administration of oleanolic acid, isolated from Swertia mussotii Franch, attenuates liver injury, inflammation, and cholestasis in bile duct-ligated rats. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 1691–1702. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, G.B.; Singh, S.; Bani, S.; Gupta, B.D.; Banerjee, S.K. Anti-inflammatory activity of oleanolic acid in rats and mice. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Title | NCT Number | Interventions | Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Bile Acids on the Secretion of Satiation Peptides in Humans | NCT01674946 | The intervention consists of intraluminal administration of TGR5 receptor (G-protein-coupled bile acid receptor) agonists—bile acids and OA—to stimulate GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide 1) secretion and evaluate their effect on glucose metabolism in healthy volunteers. The control group receives saline perfusion, with an additional arm including OA supplementation. | Completed | [165] |

| Bioavailability of Oleanolic Acid Formulated as Functional Olive Oil | NCT05529953 | The intervention involves administering to participants a functional olive oil enriched with A (30 mg OA in 55 mL olive oil) during breakfast and comparing it with a commercial control olive oil, with blood samples collected over 7 h to assess bioavailability and pharmacokinetic parameters. After a four-week washout period, participants undergo crossover administration of both types of olive oil. | Completed | [166] |

| Oleanolic Acid as Therapeutic Adjuvant for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | NCT06030544 | The intervention involves daily consumption of 55 mL of olive oil—either enriched with OA or a commercial control olive oil—by participants with type 2 diabetes, divided across three main meals, for a period of 12 months. The olive oil intake will be combined with regular monitoring of metabolic, anthropometric, and biochemical parameters. | Active, not recruiting | [167] |

| Prevention With Oleanolic Acid of Insulin Resistance | NCT05049304 | The intervention involves healthy adolescents consuming a meal containing either functional olive oil enriched with OA or regular olive oil, after which triglyceride-rich lipoprotein fractions will be isolated at 0, 2, and 5 h post-meal, and subsequently incubated with THP-1 macrophages (human monocytic leukemia cell line) to assess the anti-inflammatory activity of OA. | Completed | [168] |

| Six-Month Single-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of a Dietary Supplement on Hair Growth in 45 Volunteers | NCT06841458 | The intervention involves daily oral administration of a supplement containing OA along with other plant-based ingredients (including pumpkin seed oil, Saw Palmetto extract, and L-cystine), aimed at promoting hair growth and reducing hair loss by inhibiting 5α-reductase activity. The control group receives a placebo. | Recruiting | [169] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Günther, A.; Kulawik, M.; Sip, S.; Zalewski, P.; Jarmołowska-Jurczyszyn, D.; Stawicki, P.; Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis: Oleanolic Acid and Its Molecular Pathways. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010067

Günther A, Kulawik M, Sip S, Zalewski P, Jarmołowska-Jurczyszyn D, Stawicki P, Bednarczyk-Cwynar B. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis: Oleanolic Acid and Its Molecular Pathways. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleGünther, Andrzej, Maciej Kulawik, Szymon Sip, Przemysław Zalewski, Donata Jarmołowska-Jurczyszyn, Przemysław Stawicki, and Barbara Bednarczyk-Cwynar. 2026. "Targeting Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis: Oleanolic Acid and Its Molecular Pathways" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010067

APA StyleGünther, A., Kulawik, M., Sip, S., Zalewski, P., Jarmołowska-Jurczyszyn, D., Stawicki, P., & Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B. (2026). Targeting Oxidative Stress in Carcinogenesis: Oleanolic Acid and Its Molecular Pathways. Antioxidants, 15(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010067