Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species in Relationships Between Viral Infections and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia

Abstract

1. Introduction

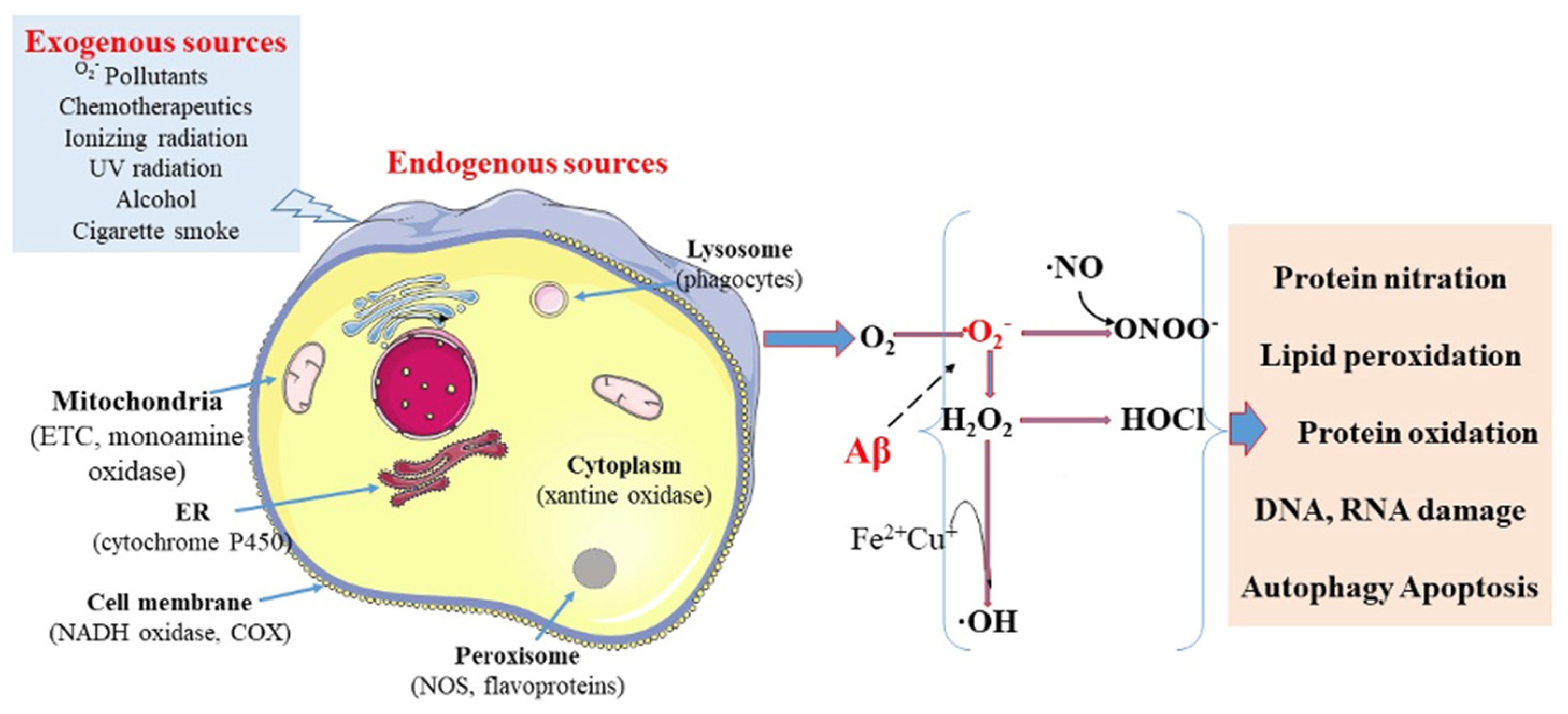

2. Reactive Oxygen Species

3. Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia (ADRD)

4. Roles of ROS in ADRD

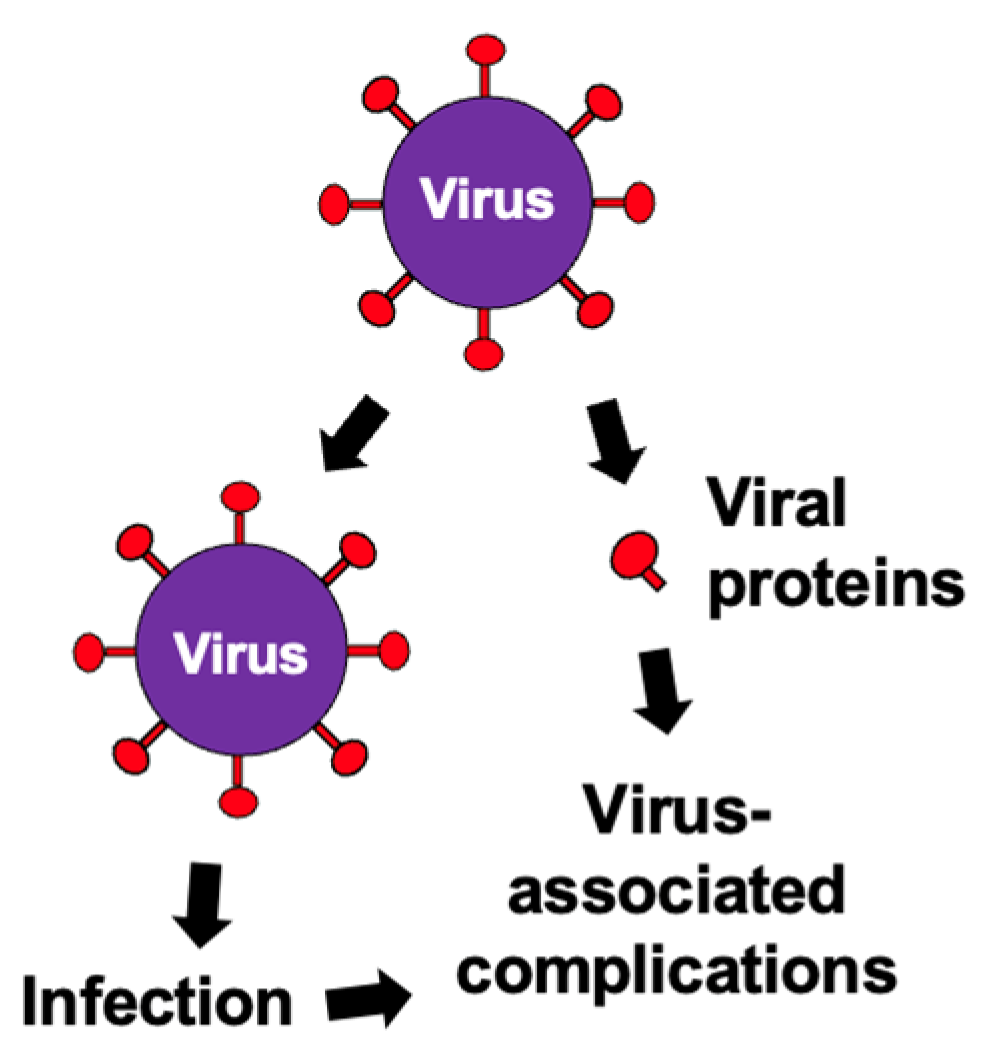

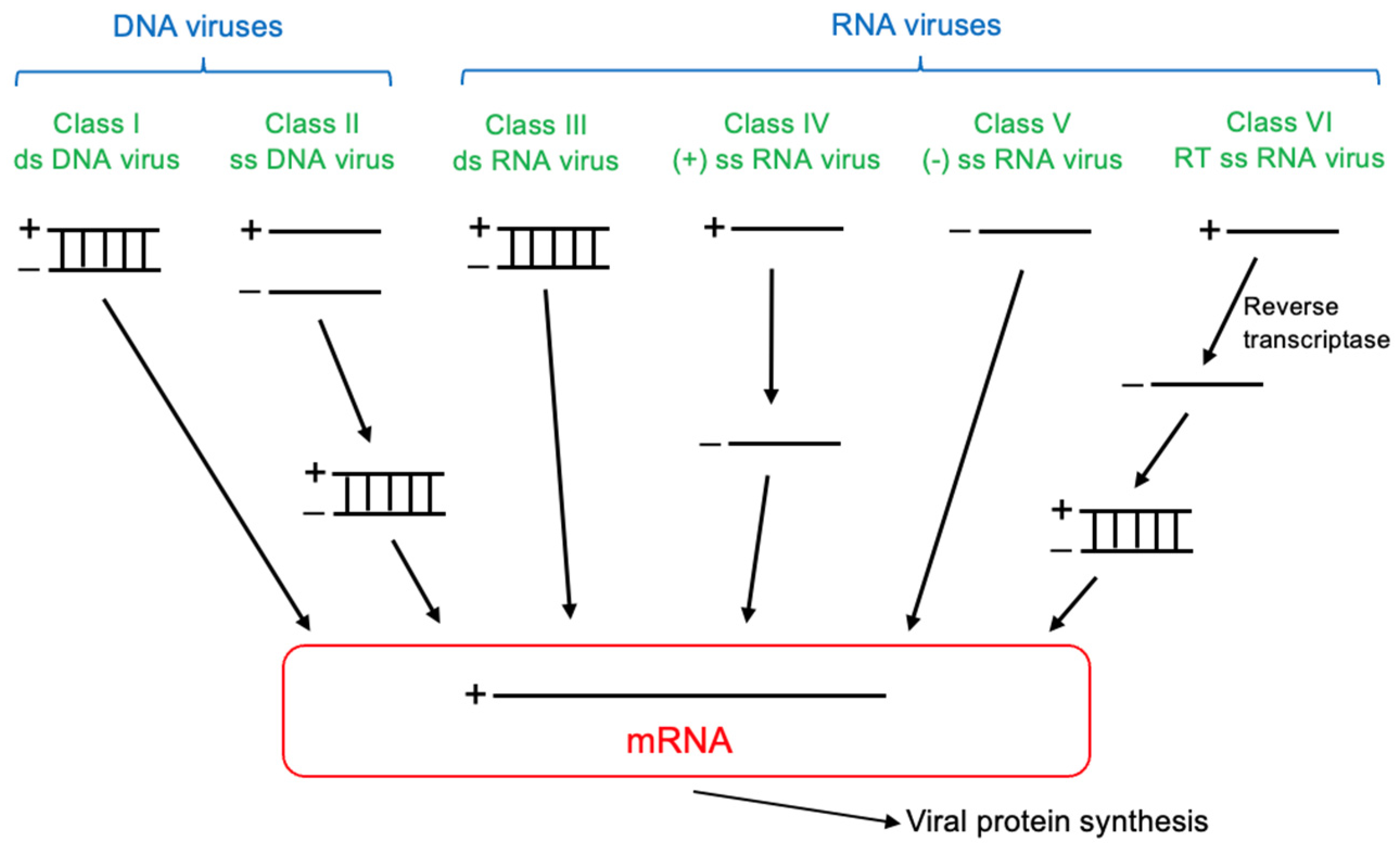

5. Relationships Between Viral Infections and ADRD

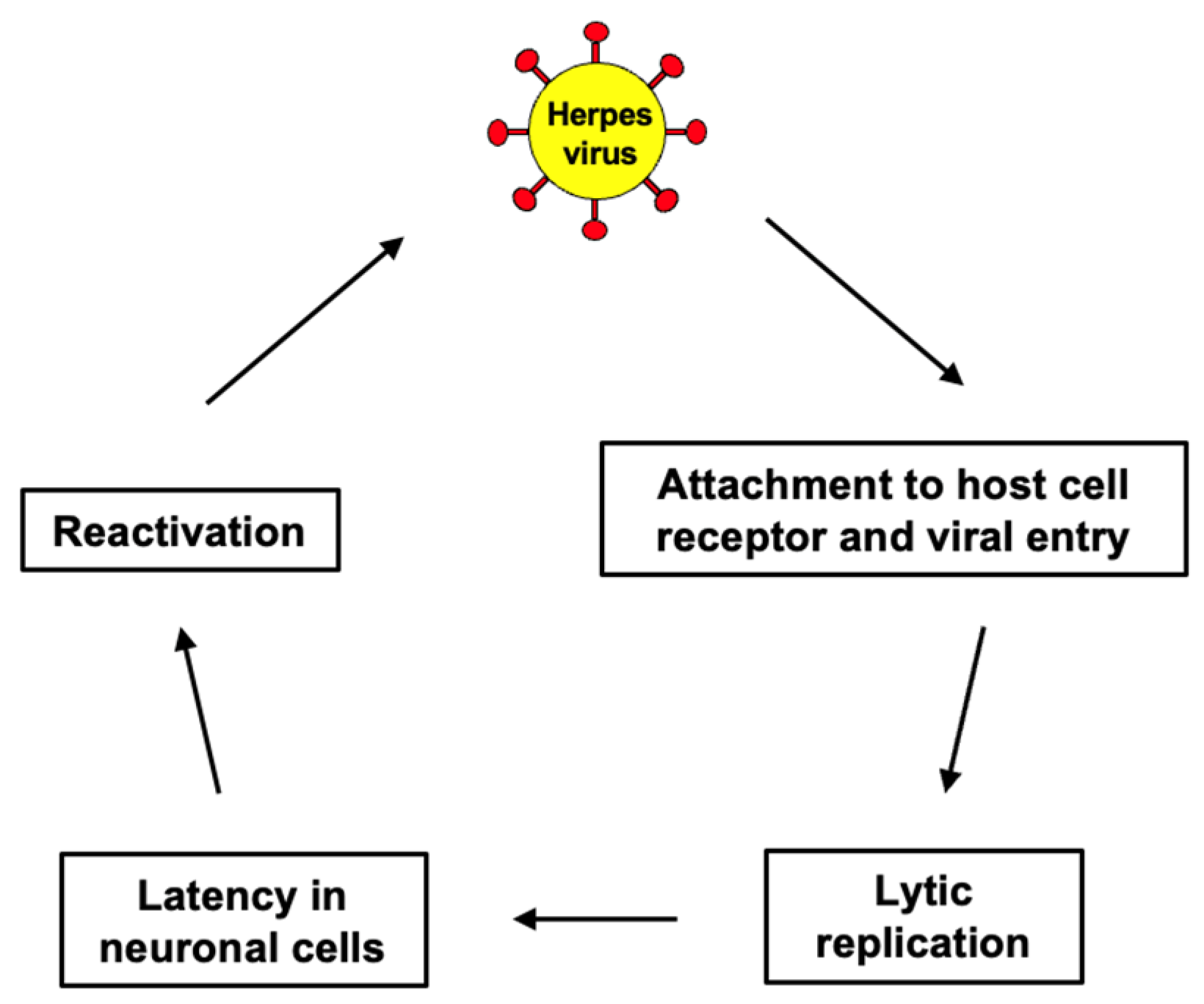

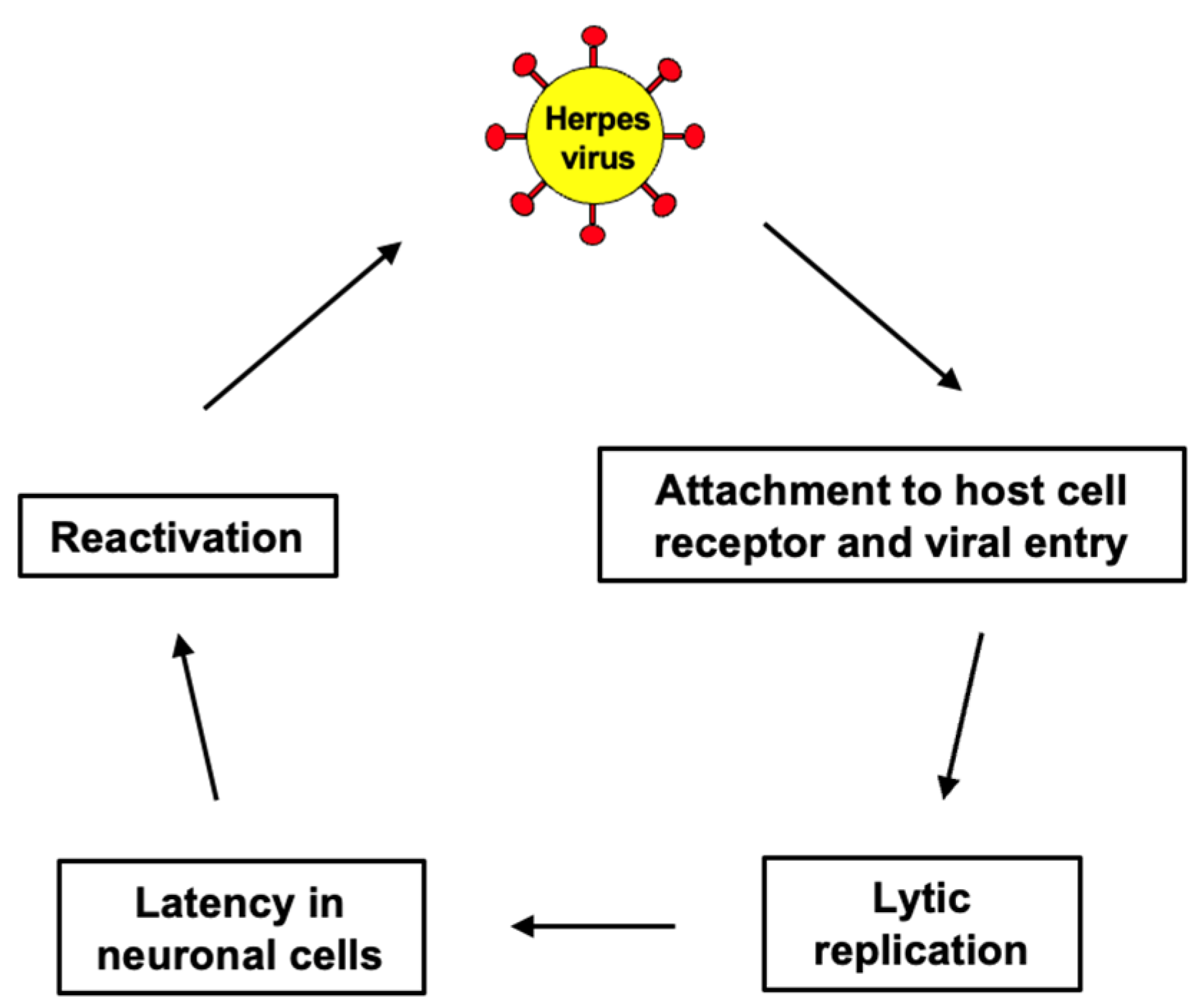

5.1. Herpes Simplex Viruses and ADRD

5.2. Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) and ADRD

5.3. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and ADRD

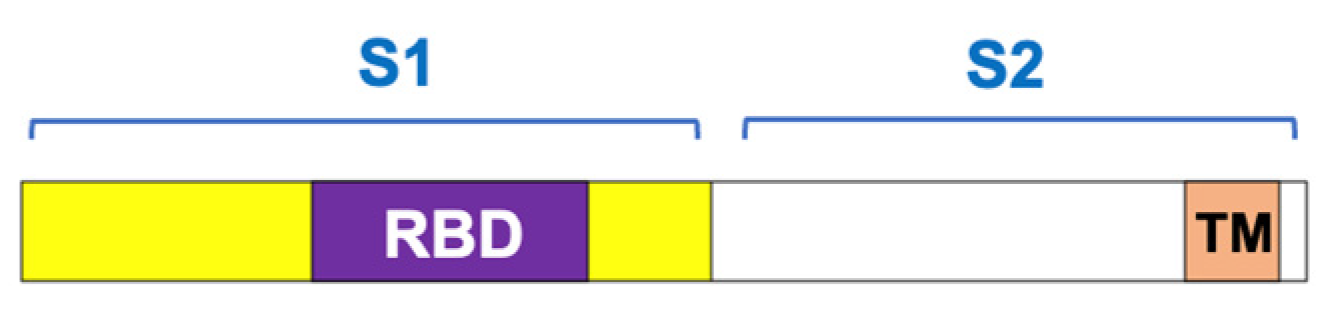

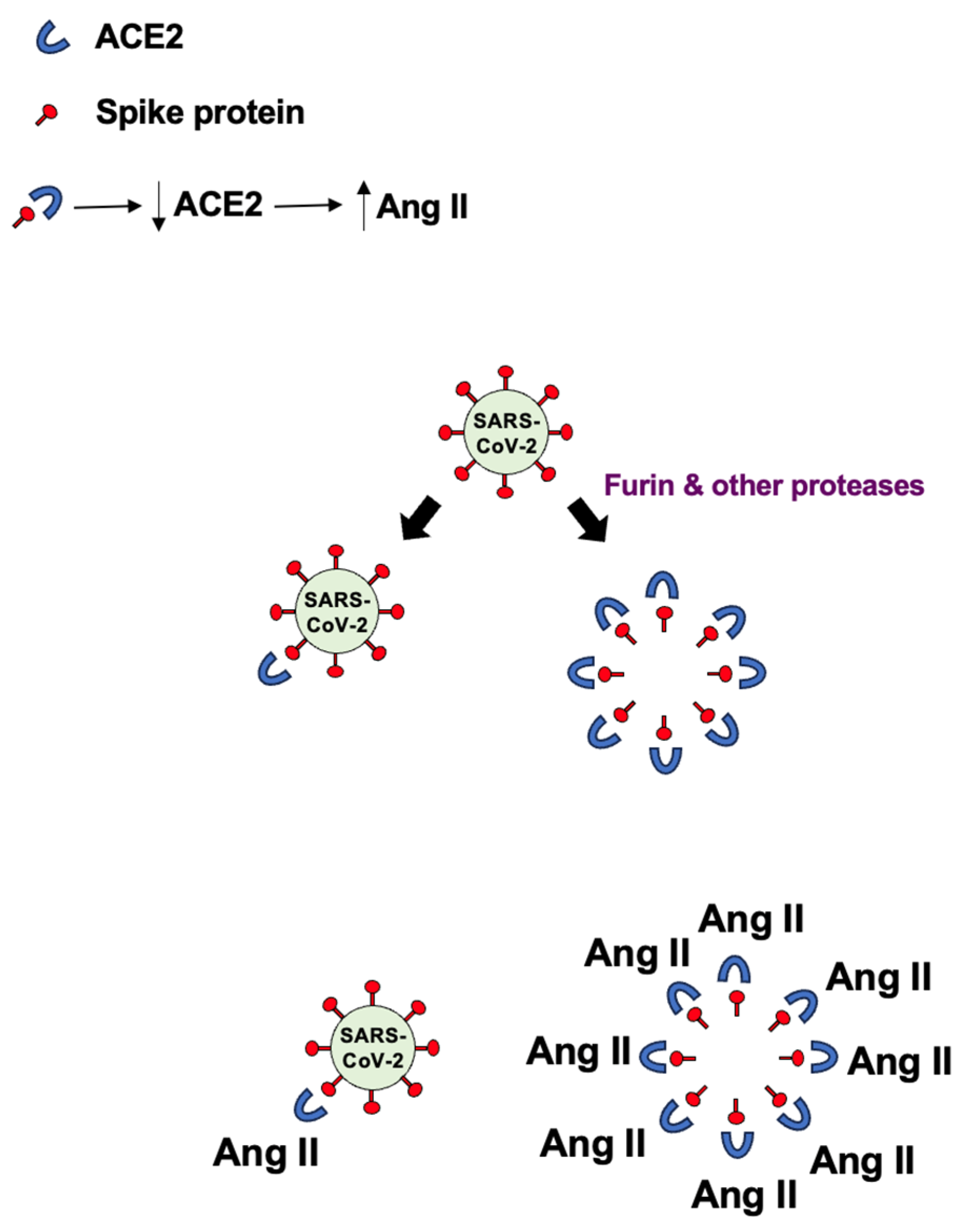

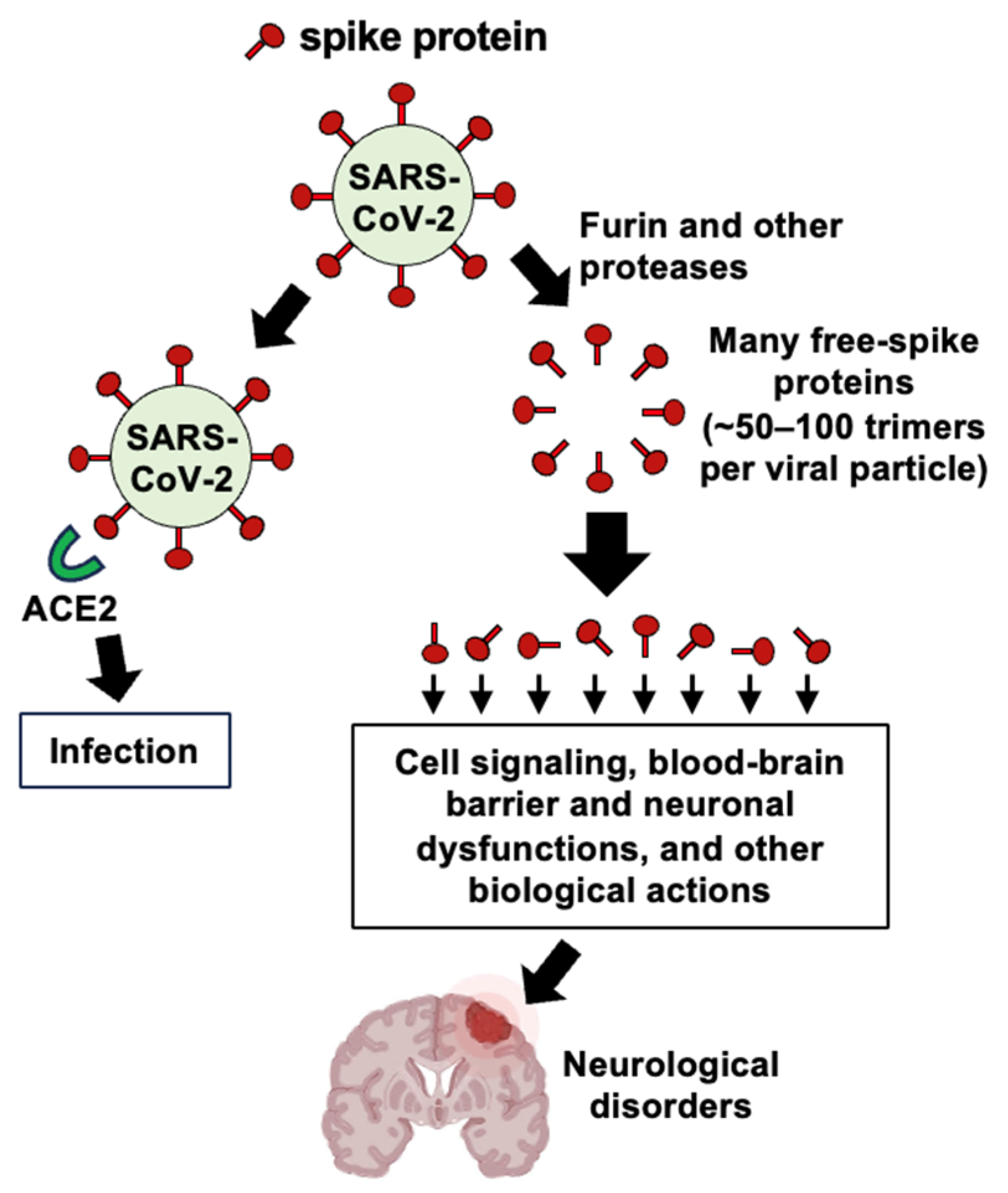

5.4. SARS-CoV-2 and ADRD

5.5. Zika Virus and ADRD

5.6. Enterovirus and ADRD

5.7. HIV and ADRD

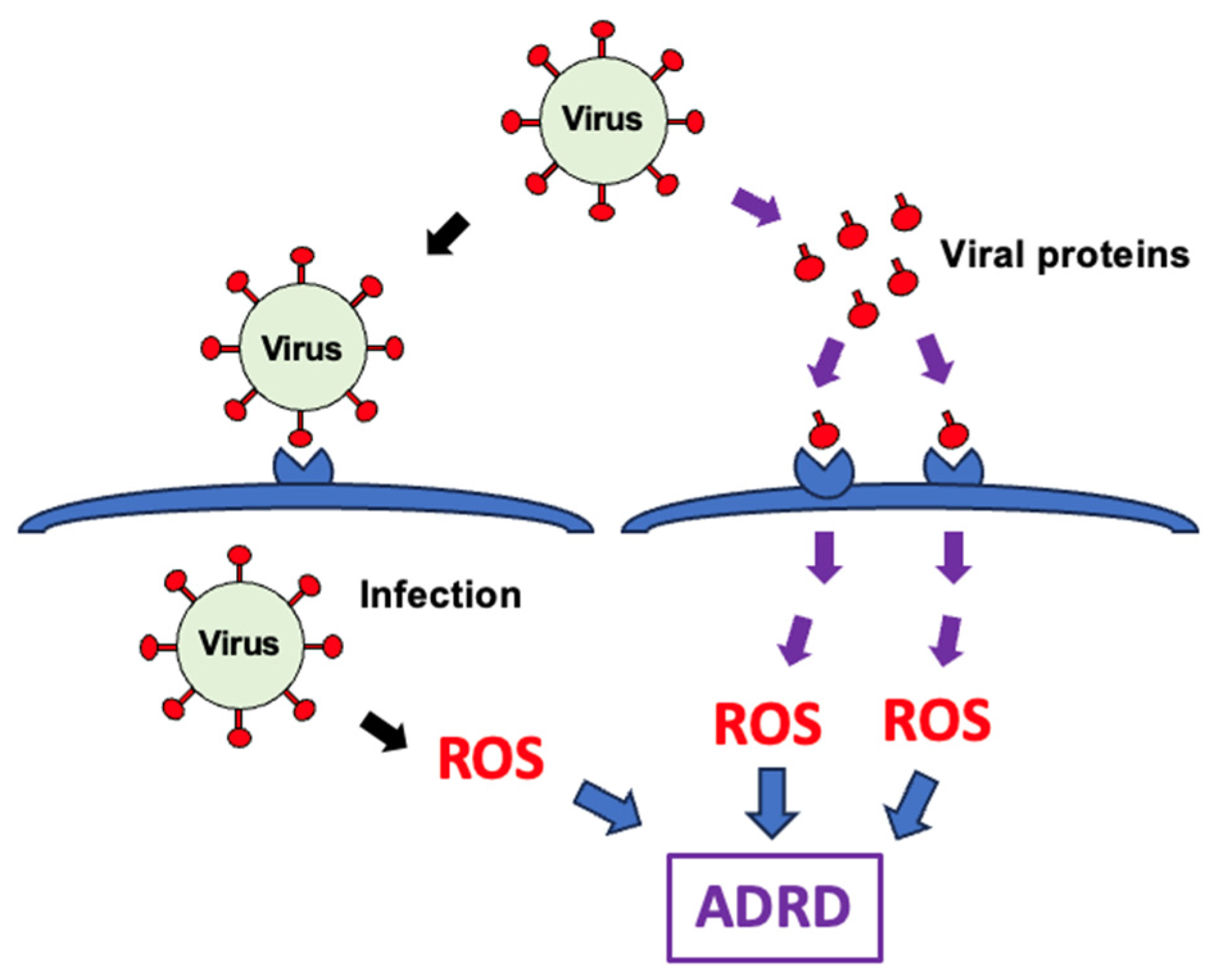

6. Cellular Production of ROS by Viruses

6.1. Cellular Production of ROS by HSV-1 and HSV-2

6.2. Cellular Production of ROS by VZV

6.3. Cellular Production of ROS by CMV

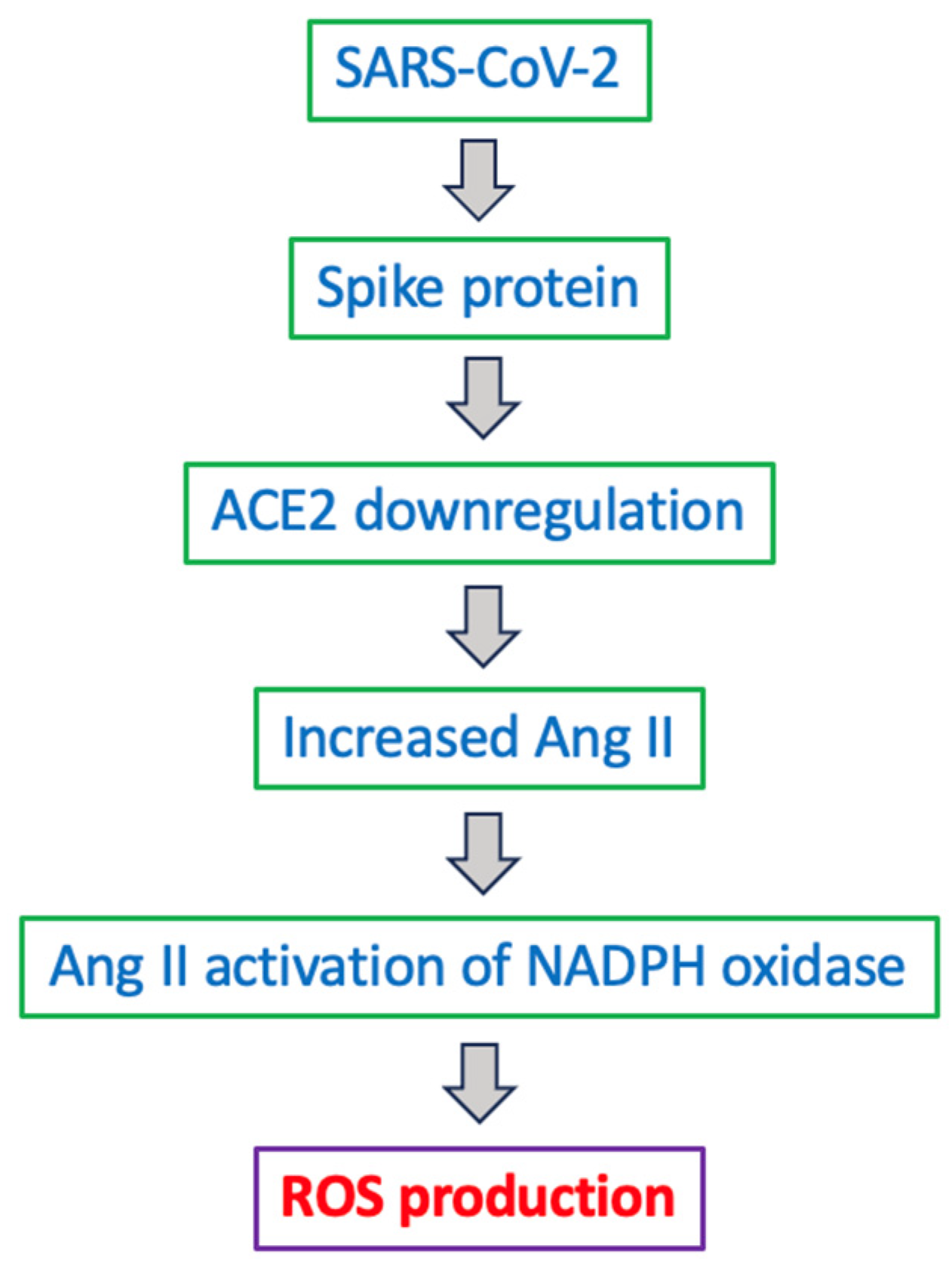

6.4. Cellular Production of ROS by Coronaviruses

6.5. Cellular Production of ROS by Zika Virus

6.6. Cellular Production of ROS by Enteroviruses

6.7. Cellular Production of ROS by HIV

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aβ | amyloid-beta |

| ACE2 | angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| APOE-ε4 | apolipoprotein E ε4 |

| BHV-1 | bovine herpesvirus 1 |

| CMV | cytomegalovirus |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| ETC | electron transport chain |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| HOCl | hypochlorous acid |

| HSV-1 | herpes simplex virus 1 |

| HSV-2 | herpes simplex virus 2 |

| KEAP1 | Kelch-like ECH-related protein 1 |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| NOS | nitric oxide synthase |

| NOX | NADPH oxidase |

| •NO | nitric oxide |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid-2–related factor 2 |

| O2 | molecular oxygen |

| •O2− | superoxide anion radical |

| •OH | hydroxyl radical |

| ONOO− | peroxynitrite |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| TLRs | toll-like receptors |

| VZV | varicella-zoster virus |

References

- Blackhurst, B.M.; Funk, K.E. Viral pathogens increase risk of neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2023, 19, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, K.S.; Leonard, H.L.; Blauwendraat, C.; Iwaki, H.; Johnson, N.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Faghri, F.; Singleton, A.B.; Nalls, M.A. Virus exposure and neurodegenerative disease risk across national biobanks. Neuron 2023, 111, 1086–1093.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippee-Brooks, M.D.; Wu, W.; Dong, J.; Pappolla, M.; Fang, X.; Bao, X. Viral infections, are they a trigger and risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease? Pathogens 2024, 13, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongi, D.; Baldelli, S. Redox imbalance and viral infections in neurodegenerative diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 6547248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, P.; Gupta, R.; Kushwaha, S.; Agarwal, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S.; Kukreti, R. Viral induced oxidative and inflammatory response in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis with identification of potential drug candidates: A systematic review using systems biology approach. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.; Laurie, C.; Mosley, R.L.; Gendelman, H.E. Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2007, 82, 297–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça-Vieira, L.R.; Aníbal-Silva, C.E.; Menezes-Neto, A.; Azevedo, E.A.N.; Zanluqui, N.G.; Peron, J.P.S.; Franca, R.F.O. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are not a key determinant for Zika virus-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Viruses 2021, 13, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.J. The viral protein fragment theory of COVID-19 pathogenesis. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 144, 110267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyubova, G.; Gychka, S.G.; Nikolaienko, S.I.; Alghenaim, F.A.; Teramoto, T.; Shults, N.V.; Suzuki, Y.J. The role of furin in the pathogenesis of COVID-19-associated neurological disorders. Life 2024, 14, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is a Virus? In Viruses and Man: A History of Interactions; Taylor, M.W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louten, J. Virus Structure and Classification. In Essential Human Virology; Louten, J., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2016; pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltimore, D. Expression of animal virus genomes. Bacteriol. Rev. 1971, 35, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V.; Krupovic, M.; Agol, V.I. The Baltimore Classification of Viruses 50 years later: How does it stand in the light of virus evolution? Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2021, 85, e0005321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, F.; Abondio, P.; Bruno, R.; Ceraudo, L.; Paparazzo, E.; Citrigno, L.; Luiselli, D.; Bruni, A.C.; Passarino, G.; Colao, R.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease as a viral disease: Revisiting the infectious hypothesis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 91, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, E.P.; Zetterberg, H.; Heslegrave, A.; Dehghan, A.; Elliott, P.; Allen, N.; Runz, H.; Laban, R.; Veleva, E.; Whelan, C.D.; et al. Plasma proteomic evidence for increased β-amyloid pathology after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, M.; Mohammadi Vadoud, S.A.; Haratian, A.; Talebi, M.; Farkhondeh, T.; Pourbagher-Shahri, A.M.; Samarghandian, S. The interplay between oxidative stress and autophagy: Focus on the development of neurological diseases. Behav. Brain Funct. 2022, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev Neurosci. 2019, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: Promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative stress: Harms and benefits for human health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 194, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.J.; Forman, H.J.; Sevanian, A. Oxidants as stimulators of signal transduction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1997, 22, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham-Huy, L.A.; He, H.; Pham-Huy, C. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 2008, 4, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, R. Oxygen radicals, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite: Redox pathways in molecular medicine. Proc. Natil. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5839–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free radicals: Properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ. J. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Biochemistry of oxidative stress. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirichen, H.; Yaigoub, H.; Xu, W.; Wu, C.; Li, R.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and their contribution in chronic kidney disease progression through oxidative stress. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 627837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, S.; Reed, T.T.; Venditti, P.; Victor, V.M. Role of ROS and RNS sources in physiological and pathological conditions. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1245049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Niculescu, A.G.; Lungu, I.I.; Radu, C.I.; Vladâcenco, O.; Roza, E.; Costăchescu, B.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, R.I. An overview of oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, M.P.; Kremer, I.N.; Hinton, L.; Zissimopoulos, J.; Whitmer, R.A.; Hummel, C.H.; Trejo, L.; Fabius, C. Impact of dementia: Health disparities, population trends, care interventions, and economic costs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1774–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahami Monfared, A.A.; Byrnes, M.J.; White, L.A.; Zhang, Q. Alzheimer’s disease: Epidemiology and clinical progression. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, V.; Bruno, F.; Altomari, N.; Bruni, G.; Smirne, N.; Curcio, S.; Mirabelli, M.; Colao, R.; Puccio, G.; Frangipane, F.; et al. Neuropsychiatric or behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): Focus on prevalence and natural history in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 832199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Lacayo, P. Biological and disease hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease defined by Alzheimer’s disease genes. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 996030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratan, Y.; Rajput, A.; Maleysm, S.; Pareek, A.; Jain, V.; Pareek, A.; Kaur, R.; Singh, G. An insight into cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthélemy, N.R.; Salvadó, G.; Schindler, S.E.; He, Y.; Janelidze, S.; Collij, L.E.; Saef, B.; Henson, R.L.; Chen, C.D.; Gordon, B.A.; et al. Highly accurate blood test for Alzheimer’s disease is similar or superior to clinical cerebrospinal fluid tests. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Gu, Y. The dopaminergic system and Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 2495–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouras, G.K.; Tsai, J.; Naslund, J.; Vincent, B.; Edgar, M.; Checler, F.; Greenfield, J.P.; Haroutunian, V.; Buxbaum, J.D.; Xu, H.; et al. Intraneuronal Abeta42 accumulation in human brain. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 156, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, M.R.; Nagele, R.G.; Wang, H.Y.; Lee, D.H. Consistent immunohistochemical detection of intracellular beta-amyloid42 in pyramidal neurons of Alzheimer’s disease entorhinal cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 2002, 333, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iulita, M.F.; Allard, S.; Richter, L.; Munter, L.M.; Ducatenzeiler, A.; Weise, C.; Do Carmo, S.; Klein, W.L.; Multhaup, G.; Cuello, A.C. Intracellular Aβ pathology and early cognitive impairments in a transgenic rat overexpressing human amyloid precursor protein: A multidimensional study. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, L.M.; Oddo, S.; Green, K.N.; McGaugh, J.L.; LaFerla, F.M. Intraneuronal Abeta causes the onset of early Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron 2005, 45, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: Where are we now? J. Neurochem. 2006, 97, 1634–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foret, M.K.; Lincoln, R.; Do Carmo, S.; Cuello, A.C.; Cosa, G. Connecting the “Dots”: From free radical lipid autoxidation to cell pathology and disease. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 12757–12787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Carmo, S.; Crynen, G.; Paradis, T.; Reed, J.; Iulita, M.F.; Ducatenzeiler, A.; Crawford, F.; Cuello, A.C. Hippocampal proteomic analysis reveals distinct pathway deregulation profiles at early and late stages in a rat model of Alzheimer’s-like amyloid pathology. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 3451–3476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhaki, R.F.; Golde, T.E.; Heneka, M.T.; Readhead, B. Do infections have a role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naughton, S.X.; Raval, U.; Pasinetti, G.M. The viral hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease: Novel insights and pathogen-based biomarkers. J. Pers. Med. 2020, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, F.; Tong, T.J.; Zhang, Z.Y.; McNutt, M.A.; Liu, X.W. Age-dependent down-regulation of mitochondrial 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase in SAM-P/8 mouse brain and its effect on brain aging. Rejuvenation Res. 2009, 12, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhed, Y.; Daiber, A.; Steven, S. Mitochondrial oxidative stress, mitochondrial DNA damage and their role in age-related vascular dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 15918–15953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, T.; Perluigi, M.; Sultana, R.; Pierce, W.M.; Klein, J.B.; Turner, D.M.; Coccia, R.; Markesbery, W.R.; Butterfield, D.A. Redox proteomic identification of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-modified brain proteins in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Insight into the role of lipid peroxidation in the progression and pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008, 30, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, F.; Coccia, R.; Cocciolo, A.; Murphy, M.P.; Cenini, G.; Head, E.; Butterfield, D.A.; Giorgi, A.; Schinina, M.E.; Mancuso, C.; et al. Impairment of proteostasis network in Down syndrome prior to the development of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology: Redox proteomics analysis of human brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Domenico, F.; Pupo, G.; Tramutola, A.; Giorgi, A.; Schininà, M.E.; Coccia, R.; Head, E.; Butterfield, D.A.; Perluigi, M. Redox proteomics analysis of HNE-modified proteins in Down syndrome brain: Clues for understanding the development of Alzheimer disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 71, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Raina, A.K.; Smith, M.A.; Sayre, L.M.; Perry, G. Hydroxynonenal, toxic carbonyls, and Alzheimer disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 2003, 24, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, R.; Robinson, R.A.S.; Di Domenico, F.; Abdul, H.M.; St Clair, D.K.; Markesbery, W.R.; Cai, J.; Pierce, W.M.; Butterfield, D.A. Proteomic identification of specifically carbonylated brain proteins in APPNLh/APPNLh × PS-1P264L/PS-1P264L human double mutant knock-in mice model of Alzheimer disease as a function of age. J. Proteomics 2011, 74, 2430–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, R.; Moreira, P.I.; Proença, T.; Deshpande, A.; Busciglio, J.; Pereira, C.; Oliveira, C.R. Brain oxidative stress in a triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, F.A.; Peeters, C.F.W.; Kester, M.I.; Harms, A.C.; Struys, E.A.; Hankemeier, T.; van Vlijmen, H.W.T.; van der Lee, S.J.; van Duijn, C.M.; Scheltens, P.; et al. Blood-based metabolic signatures in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017, 8, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Bautista, C.; Vigor, C.; Galano, J.M.; Oger, C.; Durand, T.; Ferrer, I.; Cuevas, A.; López-Cuevas, R.; Baquero, M.; López-Nogueroles, M.; et al. New screening approach for Alzheimer’s disease risk assessment from urine lipid peroxidation compounds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, E.C.B.; Dammer, E.B.; Duong, D.M.; Ping, L.; Zhou, M.; Yin, L.; Higginbotham, L.A.; Guajardo, A.; White, B.; Troncoso, J.C.; et al. Large-scale proteomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease brain and cerebrospinal fluid reveals early changes in energy metabolism associated with microglia and astrocyte activation. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canugovi, C.; Misiak, M.; Ferrarelli, L.K.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. The role of DNA repair in brain related disease pathology. DNA Repair 2013, 12, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunomura, A.; Tamaoki, T.; Motohashi, N.; Nakamura, M.; McKeel, D.W., Jr.; Tabaton, M.; Lee, H.G.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X. The earliest stage of cognitive impairment in transition from normal aging to Alzheimer disease is marked by prominent RNA oxidation in vulnerable neurons. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 71, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floyd, R.A.; Hensley, K. Oxidative stress in brain aging. Implications for therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Aging 2002, 23, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaidi, A.A.; Bush, A.I. Iron neurochemistry in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: Targets for therapeutics. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Shults, N.V.; Gychka, S.G.; Harris, B.T.; Suzuki, Y.J. Protein expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is upregulated in brains with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisiforou, A.; Zanos, P. From viral infections to Alzheimer’s disease: Unveiling the mechanistic links through systems bioinformatics. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, S128–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Galvan, V.; Lange, M.B.; Tang, H.; Sowell, R.A.; Spilman, P.; Fombonne, J.; Gorostiza, O.; Zhang, J.; Sultana, R.; et al. In vivo oxidative stress in brain of Alzheimer disease transgenic mice: Requirement for methionine 35 in amyloid beta-peptide of APP. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manczak, M.; Anekonda, T.S.; Henson, E.; Park, B.S.; Quinn, J.; Reddy, P.H. Mitochondria are a direct site of A beta accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: Implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 1437–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.H.; Tripathi, R.; Troung, Q.; Tirumala, K.; Reddy, T.P.; Anekonda, V.; Shirendeb, U.P.; Calkins, M.J.; Reddy, A.P.; Mao, P.; et al. Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics and synaptic degeneration as early events in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications to mitochondria-targeted antioxidant therapeutics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1822, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picone, P.; Nuzzo, D.; Caruana, L.; Scafidi, V.; Di Carlo, M. Mitochondrial dysfunction: Different routes to Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 780179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagno, E.; Guglielmotto, M.; Vasciaveo, V.; Tabaton, M. Oxidative stress and beta amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Which comes first: The chicken or the egg? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.D.; Chen, X.; Fu, J.; Chen, M.; Zhu, H.; Roher, A.; Slattery, T.; Zhao, L.; Nagashima, M.; Morser, J.; et al. RAGE and amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 1996, 382, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, N.M.; Evans, M.D.; Mao, W.; Nana, A.L.; Seeley, W.W.; Adame, A.; Rissman, R.A.; Masliah, E.; Mucke, L. Early neuronal accumulation of DNA double strand breaks in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2019, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palop, J.J.; Mucke, L. Network abnormalities and interneuron dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2016, 17, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danysz, W.; Parsons, C.G. Alzheimer’s disease, β-amyloid, glutamate, NMDA receptors and memantine—Searching for the connections. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 167, 324–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, P.J. Maintaining genome stability in the nervous system. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.E.; Lindahl, T. Repair and genetic consequences of endogenous DNA base damage in mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004, 38, 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foret, M.K.; Orciani, C.; Welikovitch, L.A.; Huang, C.; Cuello, A.C.; Do Carmo, S. Early oxidative stress and DNA damage in Aβ-burdened hippocampal neurons in an Alzheimer’s-like transgenic rat model. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilsoniii, D.; Bohr, V. The mechanics of base excision repair, and its relationship to aging and disease. DNA Repair 2007, 6, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praticò, D. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease: A reappraisal. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008, 29, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markesbery, W.R. Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1997, 23, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romay, M.C.; Toro, C.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L. Emerging molecular mechanisms of vascular dementia. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2019, 26, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, G.A.; Maitland, N.J.; Wilcock, G.K.; Craske, J.; Itzhaki, R.F. Latent herpes simplex virus type 1 in normal and Alzheimer’s disease brains. J. Med. Virol. 1991, 33, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, N.K.; Sharma, A.; Jha, S.K.; Ojha, S.; Chellappan, D.K.; Gupta, G.; Kesari, K.K.; Bhardwaj, S.; Shukla, S.D.; Tambuwala, M.M.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease-like perturbations in HIV-mediated neuronal dysfunctions: Understanding mechanisms and developing therapeutic strategies. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filgueira, L.; Larionov, A.; Lannes, N. The influence of virus infection on microglia and accelerated brain aging. Cells 2021, 10, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingel, A.; Lin, H.; Gavriel, Y.; Weaver, E.; Polepole, P.; Lopez, V.; Lei, Y.; Petro, T.M.; Solomon, B.; Zhang, C.; et al. Amyloid precursor protein is a restriction factor that protects against Zika virus infection in mammalian brains. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17114–17127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaki, S.D.; Vinters, H.V.; Williams, C.K.; Mareninov, S.; Khanlou, N.; Said, J.; Nemanim, N.; Gonzalez, J.; Morales, J.G.; Singer, E.J.; et al. Neuropathologic findings in elderly HIV-positive individuals. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 81, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Yang, L.; Hao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Lu, T.; Jin, W.; Dan, M.; Peng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Proteomic landscape subtype and clinical prognosis of patients with the cognitive impairment by Japanese encephalitis infection. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, M.S.; Stachowiak, A.; Mamun, A.A.; Tzvetkov, N.T.; Takeda, S.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bergantin, L.B.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Stankiewicz, A.M. Autophagy and Alzheimer’s disease: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, R.D.; Lathe, R.; Tanzi, R.E. The antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018, 14, 1602–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimer, W.A.; Vijaya Kumar, D.K.; Navalpur Shanmugam, N.K.; Rodriguez, A.S.; Mitchell, T.; Washicosky, K.J.; György, B.; Breakefield, X.O.; Tanzi, R.E.; Moir, R.D. Alzheimer’s disease-associated β-amyloid is rapidly seeded by herpesviridae to protect against brain infection. Neuron 2018, 99, 56–63.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, M.; Mee, A.; Itzhaki, R. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is located within Alzheimer’s disease amyloid plaques. J. Pathol. 2009, 217, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhaki, R.F.; Lathe, R.; Balin, B.J.; Ball, M.J.; Bearer, E.L.; Braak, H.; Bullido, M.J.; Carter, C.; Clerici, M.; Cosby, S.L.; et al. Microbes and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 51, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Readhead, B.; Haure-Mirande, J.V.; Funk, C.C.; Richards, M.A.; Shannon, P.; Haroutunian, V.; Sano, M.; Liang, W.S.; Beckmann, N.D.; Price, N.D.; et al. Multiscale analysis of independent Alzheimer’s cohorts finds disruption of molecular, genetic, and clinical networks by human herpesvirus. Neuron 2018, 99, 64–82.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, R.; Roizman, B. Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet 2001, 357, 1513–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhaki, R.F.; Lin, W.R.; Shang, D.; Wilcock, G.K.; Faragher, B.; Jamieson, G.A. Herpes simplex virus type 1 in brain and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 1997, 349, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deatly, A.M.; Haase, A.T.; Fewster, P.H.; Lewis, E.; Ball, M.J. Human herpes virus infections and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1990, 16, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nixon, R.A. Amyloid precursor protein and endosomal-lysosomal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Inseparable partners in a multifactorial disease. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 2729–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacentini, R.; Li Puma, D.D.; Ripoli, C.; Marcocci, M.E.; De Chiara, G.; Garaci, E.; Palamara, A.T.; Grassi, C. Herpes Simplex Virus type-1 infection induces synaptic dysfunction in cultured cortical neurons via GSK-3 activation and intraneuronal amyloid-β protein accumulation. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairns, D.M.; Itzhaki, R.F.; Kaplan, D.L. Potential involvement of Varicella Zoster Virus in Alzheimer’s disease via reactivation of quiescent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 88, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, I.R.A.; Neumann, M.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Alafuzoff, I.; Kril, J.; Kovacs, G.G.; Ghetti, B.; Halliday, G.; Holm, I.E.; et al. Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: An update. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.T.; Luu, I.Y.K.; Lin, F.; Vij, A.P.; Lewis, K.A.; Wilson, M.L.; Klausner, J.D. Association between herpes simplex virus 1 and dementia: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e088632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, M.A. Herpesviridae, neurodegenerative disorders and autoimmune diseases: What is the relationship between them? Viruses 2024, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.J. Alzheimer’s disease: A pathogenetic autoimmune disorder caused by herpes simplex in a gene-dependent manner. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 2010, 140539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, N.S.; Chung, C.H.; Lin, F.H.; Chiang, C.P.; Yeh, C.B.; Huang, S.Y.; Lu, R.B.; Chang, H.A.; Kao, Y.C.; Yeh, H.W.; et al. Anti-herpetic medications and reduced risk of dementia in patients with herpes simplex virus infections-a nationwide, population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Feng, L.; Wu, B.; Xia, W.; Xie, P.; Ma, S.; Liu, H.; Meng, M.; Sun, Y. The association between varicella zoster virus and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.A.J.; Veres, K.; Sørensen, H.T.; Obel, N.; Henderson, V.W. Incident herpes zoster and risk of dementia: A population-based Danish cohort study. Neurology 2022, 99, e660–e668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubak, A.N.; Como, C.N.; Hassell, J.E.; Mescher, T.; Frietze, S.E.; Niemeyer, C.S.; Cohrs, R.J.; Nagel, M.A. Targeted RNA sequencing of VZV-infected brain vascular adventitial fibroblasts indicates that amyloid may be involved in VZV vasculopathy. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 9, e1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatko Lindman, K.; Hemmingsson, E.S.; Weidung, B.; Brännström, J.; Josefsson, M.; Olsson, J.; Elgh, F.; Nordström, P.; Lövheim, H. Herpesvirus infections, antiviral treatment, and the risk of dementia-a registry-based cohort study in Sweden. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 7, e12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas-Ojer, P.; Puthenparampil, M.; Cruciani, C.; Docampo, M.J.; Martin, R.; Sospedra, M. Characterization of antigen-induced CD4+ T-cell senescence in multiple sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 790884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Q.; Lian, W.; Meng, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhuang, M.; Zheng, N.; Karlsson, I.K.; Zhan, Y. Cytomegalovirus infection and Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 11, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gate, D.; Saligrama, N.; Leventhal, O.; Yang, A.C.; Unger, M.S.; Middeldorp, J.; Chen, K.; Lehallier, B.; Channappa, D.; De Los Santos, M.B.; et al. Clonally expanded CD8 T cells patrol the cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2020, 577, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gericke, C.; Kirabali, T.; Flury, R.; Mallone, A.; Rickenbach, C.; Kulic, L.; Tosevski, V.; Hock, C.; Nitsch, R.M.; Treyer, V.; et al. Early β-amyloid accumulation in the brain is associated with peripheral T cell alterations. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 5642–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, M.N.; Heneka, M.T.; Le Page, L.M.; Limberger, C.; Morgan, D.; Tenner, A.J.; Terrando, N.; Willette, A.A.; Willette, S.A. Impact of COVID-19 on the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: A roadmap for future research. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Western, D.; Timsina, J.; Repaci, C.; Song, W.M.; Norton, J.; Kohlfeld, P.; Budde, J.; Climer, S.; Butt, O.H.; et al. Plasma proteomics of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity reveals impact on Alzheimer’s and coronary disease pathways. iScience 2023, 26, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satija, N.; Lal, S.K. The molecular biology of SARS coronavirus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1102, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yu, B.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, W.; Song, Z.G.; Hu, Y.; Tao, Z.W.; Tian, J.H.; Pei, Y.Y.; et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature 2020, 579, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of the SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, W.; He, L.; Zhang, X.; Pu, J.; Voronin, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Du, L. Characterization of the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implication for development of RBD protein as a viral attachment inhibitor and vaccine. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhi, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Bi, Z.; Zhao, Y. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020, 109, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeherman, S.; Suzuki, Y.J. Viral infection and cardiovascular disease: Implications for the molecular basis of COVID-19 pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, A.F.; Maley, A.M.; Wu, C.; Gilboa, T.; Norman, M.; Lazarovits, R.; Mao, C.P.; Newton, G.; Chang, M.; Nguyen, K.; et al. Ultra-sensitive serial profiling of SARS-CoV-2 antigens and antibodies in plasma to understand disease progression in COVID-19 patients with severe disease. Clin. Chem. 2020, 66, 1562–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, A.F.; Cheng, C.A.; Desjardins, M.; Senussi, Y.; Sherman, A.C.; Powell, M.; Novack, L.; Von, S.; Li, X.; Baden, L.R.; et al. Circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine antigen detected in the plasma of mRNA-1273 vaccine recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Swank, Z.; Bartsch, Y.C.; Burns, M.D.; Kane, A.; Boribong, B.P.; Davis, J.P.; Loiselle, M.; Novak, T.; Senussi, Y.; et al. Circulating spike protein detected in post-COVID-19 mRNA vaccine myocarditis. Circulation 2023, 147, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Chen, X.; Cai, Y.; Xia, J.; Zhou, X.; Xu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Du, C.; et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gou, X.; Pu, K.; Chen, Z.; Guo, Q.; Ji, R.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 94, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Q.; Chang, J.; Hong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, J.; Kremer, S.; Merdji, H.; Clere-Jehl, R.; Schenck, M.; Kummerlen, C.; Collange, O.; Boulay, C.; Fafi-Kremer, S.; Ohana, M.; et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2268–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douaud, G.; Lee, S.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; Arthofer, C.; Wang, C.; McCarthy, P.; Lange, F.; Andersson, J.L.R.; Griffanti, L.; Duff, E.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature 2022, 604, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, J.A.; Boutajangout, A.; Masurkar, A.V.; Betensky, R.A.; Ge, Y.; Vedvyas, A.; Debure, L.; Moreira, A.; Lewis, A.; Huang, J.; et al. Comparison of serum neurodegenerative biomarkers among hospitalized COVID-19 patients versus non-COVID subjects with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, or Alzheimer’s dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crunfli, F.; Carregari, V.C.; Veras, F.P.; Silva, L.S.; Nogueira, M.H.; Antunes, A.S.L.M.; Vendramini, P.H.; Valença, A.G.F.; Brandão-Teles, C.; Zuccoli, G.D.S.; et al. Morphological, cellular, and molecular basis of brain infection in COVID-19 patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2200960119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.L.; Masoli, J.A.H.; Delgado, J.; Pilling, L.C.; Kuo, C.L.; Kuchel, G.A.; Melzer, D. Preexisting comorbidities predicting COVID-19 and mortality in the UK Biobank Community Cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 75, 2224–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, Q.; Cui, L. The COVID-19 pandemic and Alzheimer’s disease: Mutual risks and mechanisms. Transl. Neurodegener 2022, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numbers, K.; Brodaty, H. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Davis, P.B.; Gurney, M.E.; Xu, R. COVID-19 and dementia: Analyses of risk, disparity, and outcomes from electronic health records in the US. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 17, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchetti, A.; Rozzini, R.; Guerini, F.; Boffelli, S.; Ranieri, P.; Minelli, G.; Bianchetti, L.; Trabucchi, M. Clinical presentation of COVID19 in dementia patients. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 560–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampshire, A.; Azor, A.; Atchison, C.; Trender, W.; Hellyer, P.J.; Giunchiglia, V.; Husain, M.; Cooke, G.S.; Cooper, E.; Lound, A.; et al. Cognition and memory after Covid-19 in a large community sample. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radke, J.; Meinhardt, J.; Aschman, T.; Chua, R.L.; Farztdinov, V.; Lukassen, S.; Ten, F.W.; Friebel, E.; Ishaque, N.; Franz, J.; et al. Proteomic and transcriptomic profiling of brainstem, cerebellum and olfactory tissues in early- and late-phase COVID-19. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golzari-Sorkheh, M.; Weaver, D.F.; Reed, M.A. COVID-19 as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 91, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Davis, P.B.; Volkow, N.D.; Berger, N.A.; Kaelber, D.C.; Xu, R. Association of COVID-19 with new-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2022, 89, 411–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiken, S.; Sittenfeld, L.; Dridi, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Marks, A.R. Alzheimer’s-like signaling in brains of COVID-19 patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2022, 18, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magusali, N.; Graham, A.C.; Piers, T.M.; Panichnantakul, P.; Yaman, U.; Shoai, M.; Reynolds, R.H.; Botia, J.A.; Brookes, K.J.; Guetta-Baranes, T.; et al. A genetic link between risk for Alzheimer’s disease and severe COVID-19 outcomes via the OAS1 gene. Brain 2021, 144, 3727–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, S.; Nigdelioglu Dolanbay, S.; Aslim, B. The relationship of early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease genes with COVID-19. J. Neural. Transm. 2022, 129, 847–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.L.; Pilling, L.C.; Atkins, J.L.; Masoli, J.A.H.; Delgado, J.; Kuchel, G.A.; Melzer, D. APOE e4 genotype predicts severe COVID-19 in the UK Biobank Community Cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 75, 2231–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Neal, J.; Sompol, P.; Yener, G.; Arakaki, X.; Norris, C.M.; Farina, F.R.; Ibanez, A.; Lopez, S.; Al-Ezzi, A.; et al. Parallel electrophysiological abnormalities due to COVID-19 infection and to Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 7296–7319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, D.; Wang, C.; Crawford, T.; Holland, C. Association between COVID-19 infection and new-onset dementia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Xie, Y.; Al-Aly, Z. Long-term neurologic outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2406–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila-Pérez, G.; Nogales, A.; Martín, V.; Almazán, F.; Martínez-Sobrido, L. Reverse genetic approaches for the generation of recombinant zika virus. Viruses 2018, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V.V.; Del Sarto, J.L.; Rocha, R.F.; Silva, F.R.; Doria, J.G.; Olmo, I.G.; Marques, R.E.; Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Foureaux, G.; Araújo, J.M.S.; et al. N-Methyl-d-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockade prevents neuronal death induced by Zika virus infection. mBio 2017, 8, e00350-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Choi, H.; Shin, N.; Kong, D.; Kim, N.G.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Choi, S.W.; Kim, Y.B.; Kang, K.S. Zika virus infection accelerates Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes in brain organoids. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikonov, O.S.; Chernykh, E.S.; Garber, M.B.; Nikonova, E.Y. Enteroviruses: Classification, diseases they cause, and approaches to development of antiviral drugs. Biochemistry 2018, 82, 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, W.; Omar, M. Enterovirus; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, R.E.; Tabor-Godwin, J.M.; Tsueng, G.; Feuer, R. Enterovirus infections of the central nervous system. Virology 2011, 411, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, I.P.; Vieira, T.C.R.G. Enterovirus infection and its relationship with neurodegenerative diseases. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2023, 118, e220252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grizer, C.S.; Messacar, K.; Mattapallil, J.J. Enterovirus-D68—A reemerging non-polio enterovirus that causes severe respiratory and neurological disease in children. Front. Virol. 2024, 4, 1328457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.L.; Weng, S.F.; Kuo, C.H.; Ho, H.Y. Enterovirus 71 induces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation that is required for efficient replication. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Schönbeck, U.; Sukhova, G.K.; Bourcier, T.; Bonnefoy, J.Y.; Pober, J.S.; Libby, P. Functional CD40 ligand is expressed on human vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages: Implications for CD40–CD40 ligand signaling in atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 1931–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schecter, A.D.; Berman, A.B.; Yi, L.; Mosoian, A.; McManus, C.M.; Berman, J.W.; Klotman, M.E.; Taubman, M.B. HIV envelope gp120 activates human arterial smooth muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10142–10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, G. The biology of CCR5 and CXCR4. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2009, 4, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallenberger, S.; Bosch, V.; Angliker, H.; Shaw, E.; Klenk, H.D.; Garten, W. Inhibition of furin-mediated cleavage activation of HIV-1 glycoprotein gp160. Nature 1992, 360, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, J.; Veillette, M.; Ding, S.; Zoubchenok, D.; Alsahafi, N.; Coutu, M.; Brassard, N.; Park, J.; Courter, J.R.; Melillo, B.; et al. Small CD4 mimetics prevent HIV-1 uninfected bystander CD4 + T cell killing mediated by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. EBioMedicine 2015, 3, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, N.W.; Rizza, S.A.; Badley, A.D. How much gp120 is there? J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 1273–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.K.; Cruikshank, W.W.; Raina, J.; Blanchard, G.C.; Adler, W.H.; Walker, J.; Kornfeld, H. Identification of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein in the serum of AIDS and ARC patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1992, 5, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Cornò, M.; Donninelli, G.; Varano, B.; Da Sacco, L.; Masotti, A.; Gessani, S. HIV-1 gp120 activates the STAT3/interleukin-6 axis in primary human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11045–11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, L.A.; Yi, R.; Petrusca, D.; Wang, T.; Elghouche, A.; Gupta, S.K.; Petrache, I.; Clauss, M. HIV envelope protein gp120-induced apoptosis in lung microvascular endothelial cells by concerted upregulation of EMAP II and its receptor, CXCR3. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2014, 306, L372–L382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hioe, C.E.; Tuen, M.; Vasiliver-Shamis, G.; Alvarez, Y.; Prins, K.C.; Banerjee, S.; Nádas, A.; Cho, M.W.; Dustin, M.L.; Kachlany, S.C. HIV envelope gp120 activates LFA-1 on CD4 T-lymphocytes and increases cell susceptibility to LFA-1-targeting leukotoxin (LtxA). PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Akhter, S.; Chaudhuri, A.; Kanmogne, G.D. HIV-1 gp120 induces cytokine expression, leukocyte adhesion, and transmigration across the blood-brain barrier: Modulatory effects of STAT1 signaling. Microvasc. Res. 2009, 77, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.; Perez-Guzman, P.; Hoyer, A.; Brinks, R.; Gregg, E.; Althoff, K.N.; Justice, A.C.; Reiss, P.; Gregson, S.; Smit, M. Association between HIV infection and hypertension: A global systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandeler, G.; Johnson, L.F.; Egger, M. Trends in life expectancy of HIV-positive adults on antiretroviral therapy across the globe: Comparisons with general population. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2016, 11, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri, M.; Amini, S.; Khalili, K.; Sawaya, B.E. HIV-1 associated dementia: Symptoms and causes. Retrovirology 2006, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Rose, C.E.; Collins, P.Y.; Nuche-Berenguer, B.; Sahasrabuddhe, V.V.; Peprah, E.; Vorkoper, S.; Pastakia, S.D.; Rausch, D.; Levitt, N.S. Noncommunicable diseases among HIV-infected persons in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2018, 32, S5–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastag, Z.; Fira-Mladinescu, O.; Rosca, E.C. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND): Obstacles to early neuropsychological diagnosis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 4079–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenebe, Y.; Necho, M.; Yimam, W.; Akele, B. Worldwide occurrence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and its associated factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 814362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Lu, Q.; Farrell, M.; Lappin, J.M.; Shi, J.; Lu, L.; Bao, Y. Global prevalence and burden of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder: A meta-analysis. Neurology 2020, 95, e2610–e2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmogne, G.D.; Kennedy, R.C.; Grammas, P. HIV-1 gp120 proteins and gp160 peptides are toxic to brain endothelial cells and neurons: Possible pathway for HIV entry into the brain and HIV-associated dementia. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2002, 61, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avdoshina, V.; Mocchetti, I. Recent Advances in the molecular and cellular mechanisms of gp120-mediated neurotoxicity. Cells 2022, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, L.A.; Bryer, A.; Emsley, H.C.; Khoo, S.; Solomon, T.; Connor, M.D. HIV infection and stroke: Current perspectives and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, S.; Moshahid Khan, M.; Kumar, P.; Kodidela, S.; Mirzahosseini, G.; Kumar, S.; Ishrat, T. HIV associated risk factors for ischemic stroke and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo-Allende, A.; Gutierrez, J. Role of brain arterial remodeling in HIV-associated cerebrovascular outcomes. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 593605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Muntner, P.; Alonso, A.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Das, S.R.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e56–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaria, R.N.; Akinyemi, R.; Ihara, M. Stroke injury, cognitive impairment and vascular dementia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuschmann, P.U.; Wiedmann, S.; Wellwood, I.; Rudd, A.; Di Carlo, A.; Bejot, Y.; Ryglewicz, D.; Rastenyte, D.; Wolfe, C.D. Three-month stroke outcome: The European Registers of Stroke (EROS) investigators. Neurology 2011, 76, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, R.; Inam Khan, M.; Omer Sultan, M.; Farooque, U.; Hassan, S.A.; Asghar, F.; Cheema, O.; Karimi, S.; Hasan, C.A.; Farukhuddin, F. Frequency of human immunodeficiency virus in patients admitted with acute stroke. Cureus 2020, 12, e8296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, C.; Brey, N.; Pitcher, R.D.; O’Hagan, S.; Esterhuizen, T.M.; Chow, F.C.; Decloedt, E.H. Prevalence and characteristics of HIV-associated stroke in a tertiary hospital setting in South Africa. Neurology 2022, 99, e904–e915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, H.M.; Nance, R.M.; Avoundjian, T.; Harding, B.N.; Whitney, B.M.; Chow, F.C.; Becker, K.J.; Marra, C.M.; Zunt, J.R.; Ho, E.L.; et al. Types of stroke among people living with HIV in the United States. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2021, 86, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.L.; Muo, C.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, H.J.; Chen, P.C. Incidence of stroke in patients with HIV infection: A population-based study in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, L.D.; Engsig, F.N.; Christensen, H.; Gerstoft, J.; Kronborg, G.; Pedersen, C.; Obel, N. Risk of cerebrovascular events in persons with and without HIV: A Danish nationwide population-based cohort study. AIDS 2011, 25, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, E.C.; Tureson, K.; Rotblatt, L.J.; Singer, E.J.; Thames, A.D. HIV, vascular risk factors, and cognition in the combination antiretroviral therapy era: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2021, 27, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, A.C.; Zuniga, G.; Ramirez, P.; Fernandez, R.; Wang, C.P.; Li, J.; Davila, L.; Pelton, K.; Gomez, S.; Sohn, C.; et al. A Phase IIa clinical trial to evaluate the effects of anti-retroviral therapy in Alzheimer’s disease (ART-AD). NPJ Dement. 2025, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palù, G.; Biasolo, M.A.; Sartor, G.; Masotti, L.; Papini, E.; Floreani, M.; Palatini, P. Effects of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection on the plasma membrane and related functions of HeLa S3 cells. J. Gen. Virol. 1994, 75, 3337–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavouras, J.H.; Prandovszky, E.; Valyi-Nagy, K.; Kovacs, S.K.; Tiwari, V.; Kovacs, M.; Shukla, D.; Valyi-Nagy, T. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection induces oxidative stress and the release of bioactive lipid peroxidation by-products in mouse P19N neural cell cultures. J. Neurovirol. 2007, 13, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, M.; Chen, Z.; Lang, R.; Dang, C.H.; Fowler, C.; Sloan, D.D.; Jerome, K.R. The antiapoptotic herpes simplex virus glycoprotein J localizes to multiple cellular organelles and induces reactive oxygen species formation. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.J.; Im, J.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Choi, J.M.; Lee, H.M.; Ahn, J.K. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP27 induces apoptotic cell death by increasing intracellular reactive oxygen species. Mol. Biol. 2008, 42, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.I.; Kwon, E.B.; Oh, Y.C.; Go, Y.; Choi, J.G. Mori ramulus and its major component morusin inhibit herpes simplex virus type 1 replication and the virus-induced reactive oxygen species. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2021, 49, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, T.; Lee, L.H.; Rossi, M.; Caruso, F.; Adams, S.D. In vitro analysis of the antioxidant and antiviral activity of embelin against herpes simplex virus-1. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.P.; Cheeran, M.C.; Palmquist, J.M.; Hu, S.; Lokensgard, J.R. Microglia are the major cellular source of inducible nitric oxide synthase during experimental herpes encephalitis. J. Neurovirol. 2008, 14, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, P.A.; Beck, M.A. The immune response to herpes simplex virus encephalitis in mice is modulated by dietary vitamin E. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachtele, S.J.; Hu, S.; Little, M.R.; Lokensgard, J.R. Herpes simplex virus induces neural oxidative damage via microglial cell Toll-like receptor-2. J. Neuroinflamm. 2010, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellner, L.; Thorén, F.; Nygren, E.; Liljeqvist, J.A.; Karlsson, A.; Eriksson, K. A proinflammatory peptide from herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein G affects neutrophil, monocyte, and NK cell functions. J. Immunol. 2005, 174, 2235–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellner, L.; Karlsson, J.; Fu, H.; Boulay, F.; Dahlgren, C.; Eriksson, K.; Karlsson, A. A monocyte-specific peptide from herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein G activates the NADPH-oxidase but not chemotaxis through a G-protein-coupled receptor distinct from the members of the formyl peptide receptor family. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 6080–6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Sheng, W.S.; Schachtele, S.J.; Lokensgard, J.R. Reactive oxygen species drive herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1-induced proinflammatory cytokine production by murine microglia. J. Neuroinflamm. 2011, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Dosal, R.; Horan, K.A.; Rahbek, S.H.; Ichijo, H.; Chen, Z.J.; Mieyal, J.J.; Hartmann, R.; Paludan, S.R. HSV infection induces production of ROS, which potentiate signaling from pattern recognition receptors: Role for S-glutathionylation of TRAF3 and 6. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino-Merlo, F.; Papaianni, E.; Frezza, C.; Pedatella, S.; De Nisco, M.; Macchi, B.; Grelli, S.; Mastino, A. NF-κB-dependent production of ROS and restriction of HSV-1 infection in U937 monocytic cells. Viruses 2019, 11, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.B.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, B.; Kim, S.G.; Na, S.J.; Go, Y.; Choi, H.M.; Lee, H.J.; Han, S.M.; Choi, J.G. Korean chestnut honey suppresses HSV-1 infection by regulating the ROS-NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarbeeva, D.V.; Pislyagin, E.A.; Menchinskaya, E.S.; Berdyshev, D.V.; Krylova, N.V.; Iunikhina, O.V.; Kalinovskiy, A.I.; Shchelkanov, M.Y.; Mishchenko, N.P.; Aminin, D.L.; et al. Polyphenols from Maackia amurensis heartwood protect neuronal cells from oxidative stress and prevent herpetic infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.Q.; Xu, T.; Ji, W. Herpes simplex virus 1-induced ferroptosis contributes to viral encephalitis. mBio 2023, 14, e0237022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, D.; Ma, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhu, G. BHV-1 induced oxidative stress contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction in MDBK cells. Vet. Res. 2016, 47, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, G. The differential expression of mitochondrial function-associated proteins and antioxidant enzymes during bovine herpesvirus 1 infection: A potential mechanism for virus infection-induced oxidative mitochondrial dysfunction. Mediators Inflamm. 2019, 2019, 7072917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.H.; Fu, X.; Huang, L.; Ma, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, G. The synergistic antiviral effects of GSH in combination with acyclovir against BoHV-1 infection in vitro. Acta Virol. 2016, 60, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yuan, C.; Huang, L.; Ding, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, G. The activation of p38MAPK and JNK pathways in bovine herpesvirus 1 infected MDBK cells. Vet. Res. 2016, 47, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Fu, X.; Yuan, C.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, G. Induction of oxidative DNA damage in bovine herpesvirus 1 infected bovine kidney cells (MDBK cells) and human tumor cells (A549 cells and U2OS cells). Viruses 2018, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Chen, D.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, W.; Zhu, L. Bovine herpesvirus 1 productive infection led to inactivation of Nrf2 signaling through diverse approaches. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4957878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, T.C.; Rosa, A.C.; Ferreira, H.L.; Okamura, L.H.; Oliveira, B.R.; Vieira, F.V.; Silva-Frade, C.; Gameiro, R.; Flores, E.F. Bovine herpesviruses induce different cell death forms in neuronal and glial-derived tumor cell cultures. J. Neurovirol. 2016, 22, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafuri, S.; Marullo, A.; Ciani, F.; Della Morte, R.; Montagnaro, S.; Fiorito, F.; De Martino, L. Reactive oxygen metabolites in alpha-herpesvirus-seropositive Mediterranean buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis): A preliminary study. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 21, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartak, M.; Chodkowski, M.; Słońska, A.; Bańbura, M.W.; Cymerys, J. Equine herpesvirus type 1 affects mitochondrial network morphology and reactive oxygen species generation in equine dermal cell line. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2020, 23, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodkowski, M.; Słońska, A.; Gregorczyk-Zboroch, K.; Nowak-Zyczynska, Z.; Golke, A.; Krzyżowska, M.; Bańbura, M.W.; Cymerys, J. Equid Alphaherpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) influences morphology and function of neuronal mitochondria in vitro. Pathogens 2022, 11, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, T.; Ihara, T.; Yamawaki, K.; Kamiya, H.; Sakurai, M. Generation of hydrogen peroxide by varicella-zoster virus-stimulated polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Clin. Diagn. Virol. 1994, 2, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Ihara, T.; Yamawaki, K.; Ito, M.; Kamiya, H.; Sakurai, M. Effect of varicella zoster virus antigen-antibody complexes on hydrogen peroxide generation by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Acta Paediatr. Jpn. 1994, 36, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazan, M.; Hedayati, M.; Robati, R.M.; Riahi, S.M.; Nasiri, S. Impaired oxidative status as a potential predictor in clinical manifestations of herpes zoster. J. Med. Virol. 2018, 90, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, T.; Shimokata, K.; Daikoku, T.; Fukatsu, T.; Tsutsui, Y.; Nishiyama, Y. Pathogenesis of cytomegalovirus-associated pneumonitis in ICR mice: Possible involvement of superoxide radicals. Arch. Virol. 1992, 127, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speir, E.; Shibutani, T.; Yu, Z.X.; Ferrans, V.; Epstein, S.E. Role of reactive oxygen intermediates in cytomegalovirus gene expression and in the response of human smooth muscle cells to viral infection. Circ. Res. 1996, 79, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speir, E.; Yu, Z.X.; Takeda, K.; Ferrans, V.J.; Cannon, R.O. Antioxidant effect of estrogen on cytomegalovirus-induced gene expression in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circulation 2000, 102, 2990–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.; Roh, J.; Park, C.S.; Seoh, J.Y.; Hwang, E.S. Reactive oxygen species-induced parthanatos of immunocytes by human cytomegalovirus-associated substance. Microbiol. Immunol. 2018, 62, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.A.; Norton, E.B.; Saifudeen, Z.R.; Bentrup, K.H.Z.; Katakam, P.V.; Morris, C.A.; Myers, L.; Kaur, A.; Sullivan, D.E.; Zwezdaryk, K.J. Human cytomegalovirus alters host cell mitochondrial function during acute infection. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01183-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; He, X.; Ma, S.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Jin, W.; Yan, J.; Lin, P.; et al. Suppressive effects of pterostilbene on human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection and HCMV-induced cellular senescence. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomich, O.A.; Kochetkov, S.N.; Bartosch, B.; Ivanov, A.V. Redox biology of respiratory viral infections. Viruses 2018, 10, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.W.; Wang, C.Y.; Jou, Y.J.; Yang, T.C.; Huang, S.H.; Wan, L.; Lin, Y.J.; Lin, C.W. SARS coronavirus papain-like protease induces Egr-1-dependent up-regulation of TGF-β1 via ROS/p38 MAPK/STAT3 pathway. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.W.; Lin, K.H.; Hsieh, T.H.; Shiu, S.Y.; Li, J.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like protease-induced apoptosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 46, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.Y.; Ping, Y.H.; Lee, H.C.; Chen, K.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Chan, Y.J.; Lien, T.C.; Jap, T.S.; Lin, C.H.; Kao, L.S.; et al. Open reading frame 8a of the human severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus not only promotes viral replication but also induces apoptosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 196, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, L.; Jiang, D. SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protein induced apoptosis of COS-1 mediated by the mitochondrial pathway. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 2007, 35, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, N.; Turpeinen, H.; Oksanen, A.; Hämäläinen, S.; Huttunen, R.; Uusitalo-Seppälä, R.; Rintala, E.; Aittoniemi, J.; Pesu, M. The plasma level of proprotein convertase FURIN in patients with suspected infection in the emergency room: A prospective cohort study. Scand. J. Immunol. 2015, 82, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.W.; Ma, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, J.W.; Chen, Y.D. The association between plasma furin and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langnau, C.; Rohlfing, A.K.; Gekeler, S.; Günter, M.; Pöschel, S.; Petersen-Uribe, Á.; Jaeger, P.; Avdiu, A.; Harm, T.; Kreisselmeier, K.P.; et al. Platelet activation and plasma levels of furin are associated with prognosis of patients with coronary artery disease and COVID-19. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2080–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, E.; Inigo, J.; Chandra, D.; Chaves, L.; Reynolds, J.L.; Aalinkeel, R.; Schwartz, S.A.; Khmaladze, A.; Mahajan, S.D. Mitochondrial dynamics in SARS-COV2 spike protein treated human microglia: Implications for Neuro-COVID. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021, 16, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, X.; Xue, M.; Liu, J.; Shang, G.; Jiang, M.; Chen, D.; Liu, B.; Wang, Y.; Jia, X.; et al. SARS-COV-2 spike protein promotes RPE cell senescence via the ROS/P53/P21 pathway. Biogerontology 2023, 24, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, L.; Jin, F.; Liu, Y.; Yang, B.; Meng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, F. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 exposure increases susceptibility to angiotensin II-induced hypertension in rats by promoting central neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Neurochem. Res. 2023, 48, 3016–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; He, L.; Huang, R.; Alvarez, J.F.; Yang, D.H.; Sun, Q.; Wang, F.; Peng, Z.; Jiang, N.; Su, L. Synergistic effect of elevated glucose levels with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induced NOX-dependent ROS production in endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 6039–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.; Patra, T.; Vijayamahantesh; Ray, R. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces paracrine senescence and leukocyte adhesion in endothelial cells. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0079421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Z.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, B.; Du, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hou, S.; Yang, Y. Coenzyme Q10 attenuates human platelet aggregation induced by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein via reducing oxidative stress in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesiów, M.K.; Witwicki, M.; Tan, N.K.; Graziotto, M.E.; New, E.J. Unravelling the mystery of COVID-19 pathogenesis: Spike protein and Cu can synergize to trigger ROS production. Chemistry 2023, 29, e202301530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberger, J.S.; Hou, W.; Shields, D.; Fisher, R.; Epperly, M.W.; Sarkaria, I.; Wipf, P.; Wang, H. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces oxidative stress and senescence in mouse and human lung. In Vivo 2024, 38, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, T.V.; Rethi, L.; Lee, T.W.; Higa, S.; Kao, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J. Spike protein impairs mitochondrial function in human cardiomyocytes: Mechanisms underlying cardiac injury in COVID-19. Cells 2023, 12, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tin, H.; Rethi, L.; Higa, S.; Kao, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J. Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 activates cardiac fibrogenesis through NLRP3 inflammasomes and NF-κB signaling. Cells 2024, 13, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojkova, D.; Wagner, J.U.G.; Shumliakivska, M.; Aslan, G.S.; Saleem, U.; Hansen, A.; Luxán, G.; Günther, S.; Pham, M.D.; Krishnan, J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects and induces cytotoxic effects in human cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 2207–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, W.; Burnett, F.N.; Pandey, A.; Ghoshal, P.; Singla, B.; Simon, A.B.; Derella, C.C.; Addo, S.A.; Harris, R.A.; Lucas, R.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein stimulates macropinocytosis in murine and human macrophages via PKC-NADPH oxidase signaling. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, N.B.F.; Fantone, K.M.; Sarr, D.; Ashtiwi, N.M.; Channell, S.; Grenfell, R.F.Q.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Rada, B. Variant-dependent oxidative and cytokine responses of human neutrophils to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and anti-spike IgG1 antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1255003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Toyoda, M.; Kuwata, T.; Terasawa, H.; Tokugawa, U.; Monde, K.; Sawa, T.; Ueno, T.; Matsushita, S. Differential ability of spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 variants to downregulate ACE2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, S.; Gou, J.; Wen, Y.; Fan, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, G.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Z. Spike-mediated ACE2 down-regulation was involved in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Infect. 2022, 85, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Fox, D.M.; Gao, C.; Stanley, S.A.; Luo, K. SARS-CoV-2 down-regulates ACE2 through lysosomal degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2022, 33, ar147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Schiavon, C.R.; He, M.; Chen, L.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, Q.; Cho, Y.; Andrade, L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein impairs endothelial function via downregulation of ACE 2. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1323–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, Y.; Li, J.; Venzon, D.J.; Berzofsky, J.A. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein suppresses ACE2 and Type I interferon expression in primary cells from macaque lung bronchoalveolar lavage. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 658428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, R.L.; Bombassaro, B.; Monfort-Pires, M.; Mansour, E.; Palma, A.C.; Ribeiro, L.C.; Ulaf, R.G.; Bernardes, A.F.; Nunes, T.A.; Agrela, M.V.; et al. Plasma angiotensin II is increased in critical coronavirus disease 2019. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 847809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl-Schwaighofer, R.; Hödlmoser, S.; Domenig, O.; Krenn, K.; Eskandary, F.; Krenn, S.; Schörgenhofer, C.; Rumpf, B.; Karolyi, M.; Traugott, M.T.; et al. The systemic renin-angiotensin system in COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Hu, R.; Zhang, C.; Ren, W.; Yu, A.; Zhou, X. Elevation of plasma angiotensin II level is a potential pathogenesis for the critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyerstedt, S.; Casaro, E.B.; Rangel, É.B. COVID-19: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and tissue susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 40, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshotels, M.R.; Xia, H.; Sriramula, S.; Lazartigues, E.; Filipeanu, C.M. Angiotensin II mediates angiotensin converting enzyme type 2 internalization and degradation through an angiotensin II type I receptor-dependent mechanism. Hypertension 2014, 64, 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, E.; Cojocaru, C.; Vlad, C.E.; Eva, L. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in long COVID’s cardiovascular injuries. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Arif, G.; Farhat, A.; Khazaal, S.; Annweiler, C.; Kovacic, H.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Fajloun, Z.; Khattar, Z.A.; Sabatier, J.M. The renin-angiotensin system: A key role in SARS-CoV-2-induced COVID-19. Molecules 2021, 26, 6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, E.; Ananiev, J.; Yovchev, Y.; Arabadzhiev, G.; Abrashev, H.; Abrasheva, D.; Atanasov, V.; Kostandieva, R.; Mitev, M.; Petkova-Parlapanska, K.; et al. COVID-19 complications: Oxidative stress, inflammation, and mitochondrial and endothelial dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, J.; Wang, P.H.; Yang, N.; Huang, J.; Ou, J.; Xu, T.; Zhao, X.; Liu, T.; Huang, X.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike promotes inflammation and apoptosis through autophagy by ROS-suppressed PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Yuan, C.; Yang, S.; Ma, Z.; Li, W.; Mao, L.; Jiao, P.; Liu, W. The role of reactive oxygen species in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) infection-induced cell death. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelesidis, T.; Madhav, S.; Petcherski, A.; Cristelle, H.; O’Connor, E.; Hultgren, N.W.; Ritou, E.; Williams, D.S.; Shirihai, O.S.; Reddy, S.T. The ApoA-I mimetic peptide 4F attenuates in vitro replication of SARS-CoV-2, associated apoptosis, oxidative stress and inflammation in epithelial cells. Virulence 2021, 12, 2214–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yang, L.; Han, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, T.; Zheng, F.; Yang, J.; Guan, F.; Xie, J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein enhances the level of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.Y.; Moriyama, M.; Chang, M.F.; Ichinohe, T. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus viroporin 3a activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, G.K.; Dilawari, R.; Modanwal, R.; Talukdar, S.; Dhiman, A.; Raje, C.I.; Raje, M. Excess iron aggravates the severity of COVID-19 infection. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 208, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.H.; Luo, X.Q.; Ma, K.; Shao, J.B.; Zhang, G.H.; Liu, Z.G.; Liu, D.B.; Zhang, H.P.; Yang, P.C. Superoxide dismutase prevents SARS-CoV-2-induced plasma cell apoptosis and stabilizes specific antibody induction. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 5397733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simanjuntak, Y.; Liang, J.J.; Chen, S.Y.; Li, J.K.; Lee, Y.L.; Wu, H.C.; Lin, Y.L. Ebselen alleviates testicular pathology in mice with Zika virus infection and prevents its sexual transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.T.; Ferraz, A.C.; da Silva Caetano, C.C.; da Silva Menegatto, M.B.; Dos Santos Pereira Andrade, A.C.; Lima, R.L.S.; Camini, F.C.; Pereira, S.H.; da Silva Pereira, K.Y.; de Mello Silva, B.; et al. Zika virus induces oxidative stress and decreases antioxidant enzyme activities in vitro and in vivo. Virus Res. 2020, 286, 198084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, D.; Li, Y.; Qin, L.; Wan, Q.; Hu, H.; Wu, M.; Feng, Y.; Schang, L.; Weiss, R.; et al. Erp57 facilitates ZIKV-induced DNA damage via NS2B/NS3 complex formation. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2417864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, W.H.; Hsieh, H.L.; Lee, I.T.; Yang, C.M. Enterovirus 71 induces integrin beta1/EGFR-Rac1-dependent oxidative stress in SK-N-SH cells: Role of HO-1/CO in viral replication. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 226, 3316–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Tian, X.; Zou, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Zheng, N.; Wu, Z. Harmine, a small molecule derived from natural sources, inhibits enterovirus 71 replication by targeting NF-kappaB pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 60, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.L.; Wu, C.H.; Chien, K.Y.; Lai, C.H.; Li, G.J.; Liu, Y.Y.; Lin, G.; Ho, H.Y. Enteroviral 2B interacts with VDAC3 to regulate reactive oxygen species generation that is essential to viral replication. Viruses 2022, 14, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, G.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Ma, T. Berberine prevents lethal EV71 neurological infection in newborn mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1027566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Chen, T.; Song, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, F.; Luo, G.; Wang, H. Enterovirus 71 leads to abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells. Virus Res. 2024, 339, 199267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Guo, X.; Lin, B.; Huang, R.; Li, H.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Shang, Y.; Wu, Y. Magnolol against enterovirus 71 by targeting Nrf2-SLC7A11-GSH pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bai, Z.; Li, C.; Sheng, C.; Zhao, X. EV71 infection induces cell apoptosis through ROS generation and SIRT1 activation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 121, 4321–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, L.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Xiang, Q.; Luo, Z.; Wang, W.; Xu, W.; Wu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; et al. Enterovirus 71 induces neural cell apoptosis and autophagy through promoting ACOX1 downregulation and ROS generation. Virulence 2020, 11, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ning, Z.; Liu, X.; Su, J.; Chen, D.; Lai, J.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Zhu, B. Ebselen inhibits enterovirus A71-induced apoptosis through reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling pathway. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 2991–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursu, O.N.; Sauter, M.; Ettischer, N.; Kandolf, R.; Klingel, K. Heme oxygenase-1 mediates oxidative stress and apoptosis in coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 33, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, J.; Yu, S.; Liu, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhong, J.; Liang, Y.; Ta, N.; Yin, X.; Zhao, D. Nox4-dependent ROS production is involved in CVB3-induced myocardial apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 1641–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Shi, P.; Wu, J.; Li, F.; Chen, Y. LncRNA XIST knockdown reduces myocardial damage in myocarditis by targeting the miR-140-3p/RIPK1 axis. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2024, 40, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Lin, L.; Yao, T.; Yao, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Jingfang Granule mitigates coxsackievirus B3-induced myocardial damage by modulating mucolipin 1 expression. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 320, 117396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, A.R.; Das, S.; Padgett, L.E.; Koenig, Z.E.; Tse, H.M. Superoxide production by NADPH oxidase intensifies macrophage antiviral responses during diabetogenic coxsackievirus infection. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Shin, O.S. Stress granules inhibit Coxsackievirus B3-mediated cell death via reduction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and viral extracellular release. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Exosomal let-7a-5p derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells alleviates coxsackievirus B3-induced cardiomyocyte ferroptosis via the SMAD2/ZFP36 signal axis. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2024, 25, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreck, R.; Rieber, P.; Baeuerle, P.A. Reactive oxygen intermediates as apparently widely used messengers in the activation of the NF-kappa B transcription factor and HIV-1. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönnerborg, A.; Carlin, G.; Akerlund, B.; Jarstrand, C. Increased production of malondialdehyde in patients with HIV infection. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1988, 20, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, H.P.; Gmünder, H.; Hartmann, M. Low concentrations of acid-soluble thiol (cysteine) in the blood plasma of HIV-1 infected patients. Biol. Chem. Hoppe Seyler 1989, 370, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, S.A.; Brooke, S.M.; Sapolsky, R.M. Mechanisms of estrogenic protection against gp120-induced neurotoxicity. Exp. Neurol. 2001, 168, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatrov, V.A.; Ratter, F.; Gruber, A.; Dröge, W.; Lehmann, V. HIV type 1 glycoprotein amplifies tumor necrosis factor-induced NF-kappa B activation in Jurkat cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1996, 12, 1209–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foga, I.O.; Nath, A.; Hasinoff, B.B.; Geiger, J.D. Antioxidants and dipyridamole inhibit HIV-1 gp120-induced free radical-based oxidative damage to human monocytoid cells. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 1997, 16, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista, A.P. Chronic alcohol intoxication attenuates human immunodeficiency virus-1 glycoprotein 120-induced superoxide anion release by isolated Kupffer cells. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 1998, 22, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, B.; Corsini, E.; Binaglia, M.; Galli, C.L.; Marinovich, M. Reactive oxygen species generated by glia are responsible for neuron death induced by human immunodeficiency virus-glycoprotein 120 in vitro. Neuroscience 2001, 107, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, S.M.; McLaughlin, J.R.; Cortopassi, K.M.; Sapolsky, R.M. Effect of GP120 on glutathione peroxidase activity in cortical cultures and the interaction with steroid hormones. J. Neurochem. 2002, 81, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.A.; Megyesi, J.F.; Wilson, J.X.; Crukley, J.; Laubach, V.E.; Hammond, R.R. Antioxidant protection from HIV-1 gp120-induced neuroglial toxicity. J. Neuroinflamm. 2004, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.; Pahan, K. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 induces apoptosis in human primary neurons through redox-regulated activation of neutral sphingomyelinase. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 9531–9540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, T.O.; Uras, F.; Banks, W.A.; Ercal, N. A novel antioxidant N-acetylcysteine amide prevents gp120- and Tat-induced oxidative stress in brain endothelial cells. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 201, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, R.N.; Pahan, K. Differential regulation of Mn-superoxide dismutase in neurons and astroglia by HIV-1 gp120: Implications for HIV-associated dementia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 42, 1866–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Allen, J.E.; Zhu, X.; Callen, S.; Buch, S. Cocaine and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 mediate neurotoxicity through overlapping signaling pathways. J. Neurovirol 2009, 15, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harshithkumar, R.; Shah, P.; Jadaun, P.; Mukherjee, A. ROS chronicles in HIV infection: Genesis of oxidative stress, associated pathologies, and therapeutic strategies. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 8852–8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, S.; Byrnes, S.; Cochrane, C.; Roche, M.; Estes, J.D.; Selemidis, S.; Angelovich, T.A.; Churchill, M.J. The role of oxidative stress in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2021, 13, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Cognitive Symptoms | Behavioral/Psychiatric Symptoms | Functional Decline | Care Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|